Therapeutic Delivery of Phloretin by Mixed Emulsifier-Stabilized Nanoemulsion Alleviated Cerebral Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Preparation of NE-PHL

2.3. Characterization

2.3.1. Morphological Observation

2.3.2. Droplet Size, Size Distribution, and Zeta Potential

2.3.3. Encapsulation Efficiency and Drug Loading

2.3.4. Stability Evaluation

2.3.5. Drug Release in Vitro

2.4. Pharmacokinetic Studies

2.4.1. Animals

2.4.2. Pharmacokinetic Protocol

2.4.3. Tissue Distribution

2.5. Pharmacological Studies

2.5.1. Ischemic Stroke Induction—MCAO Model

2.5.2. Groups and Treatment

2.5.3. Behavioral Testing

2.5.4. TTC Staining

2.5.5. Cerebral Oxidative Stress and Neuroinflammation Determination

2.6. RNA Sequencing Analysis

2.7. Preliminary Safety Evaluation in Vivo

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

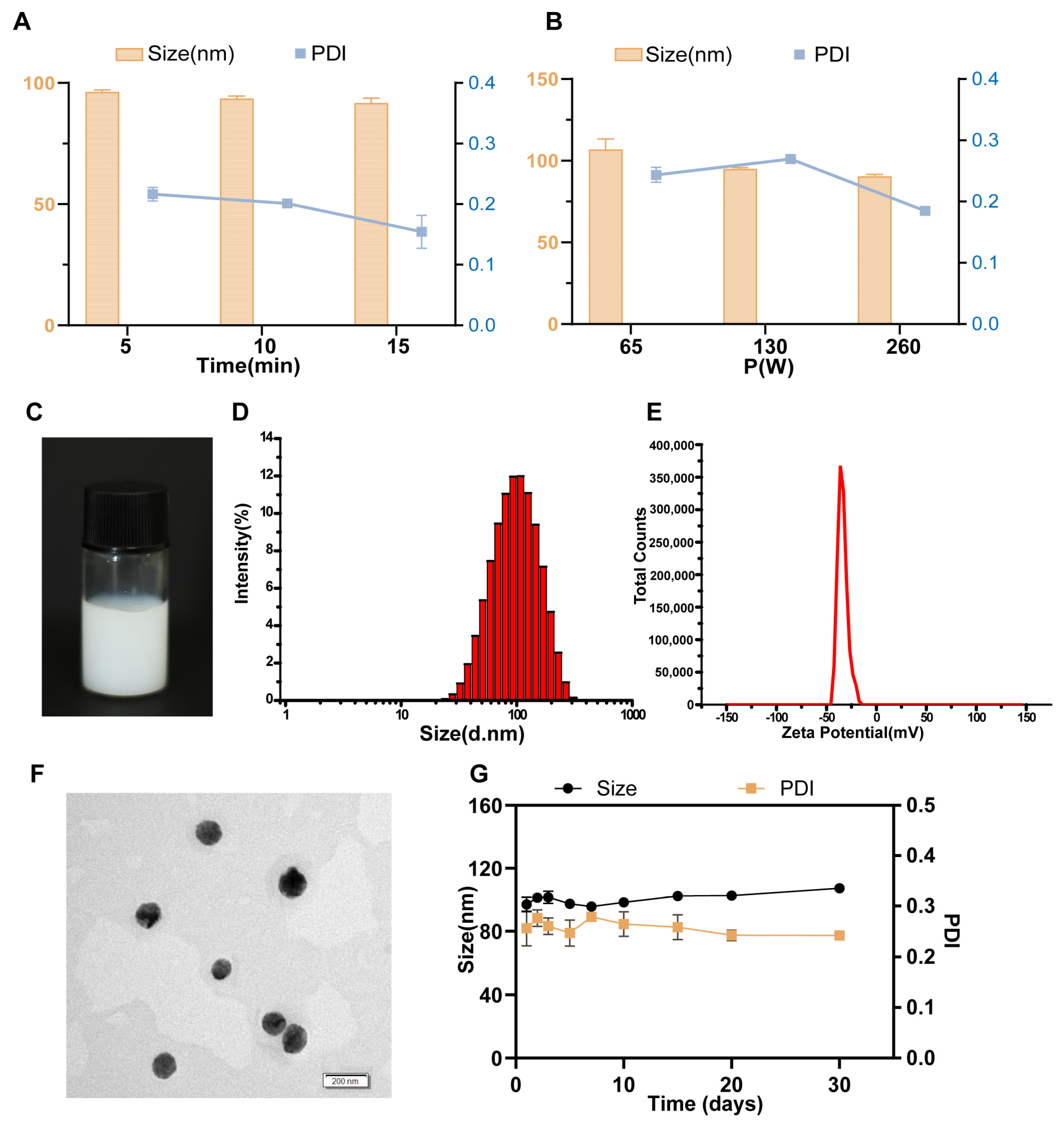

3.1. Optimized NE-PHL Formulation

3.2. Characterization

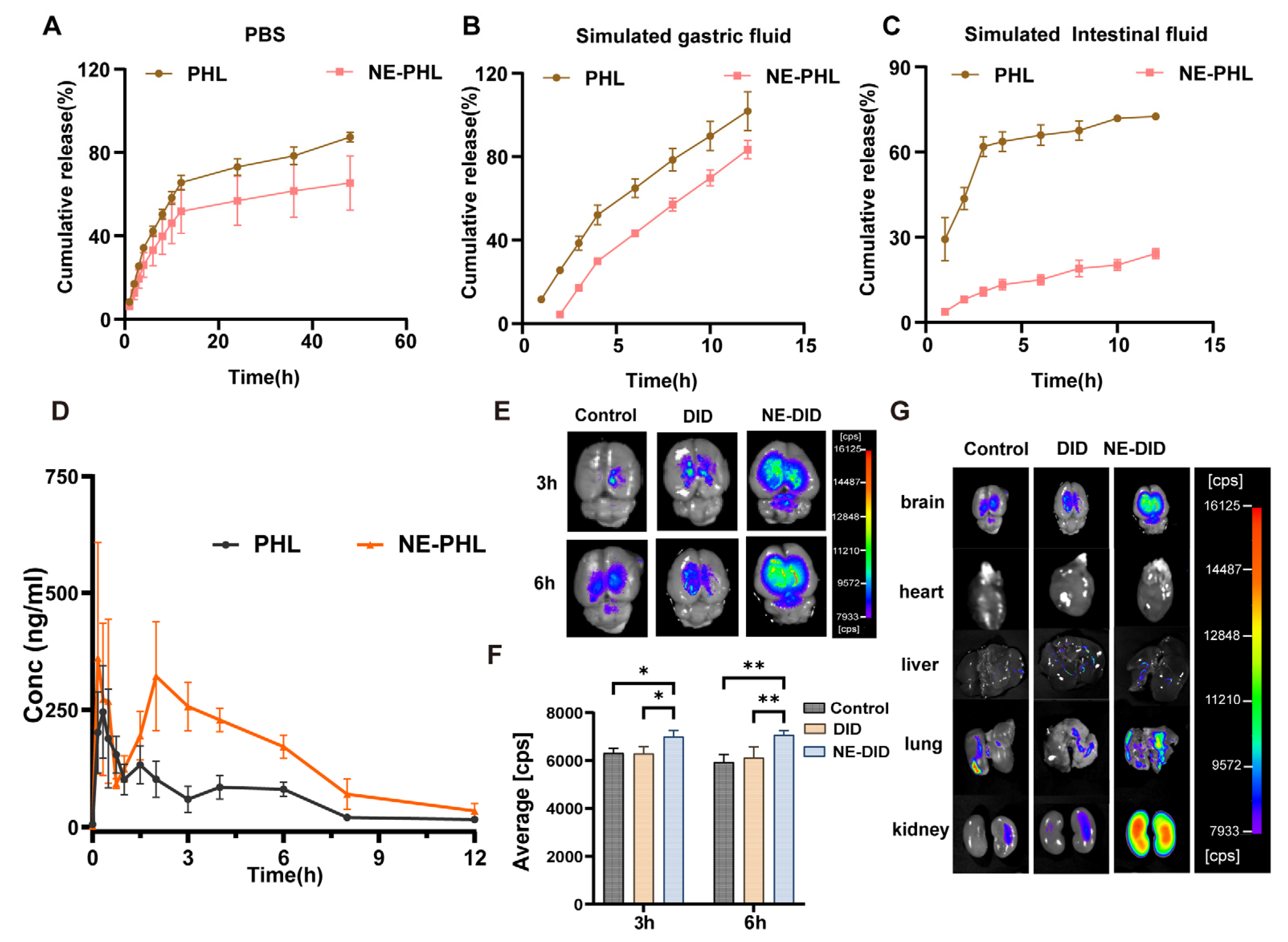

3.3. Drug Release in Vitro

3.4. NE-PHL Increased PHL Levels in Blood and Brain of Rats

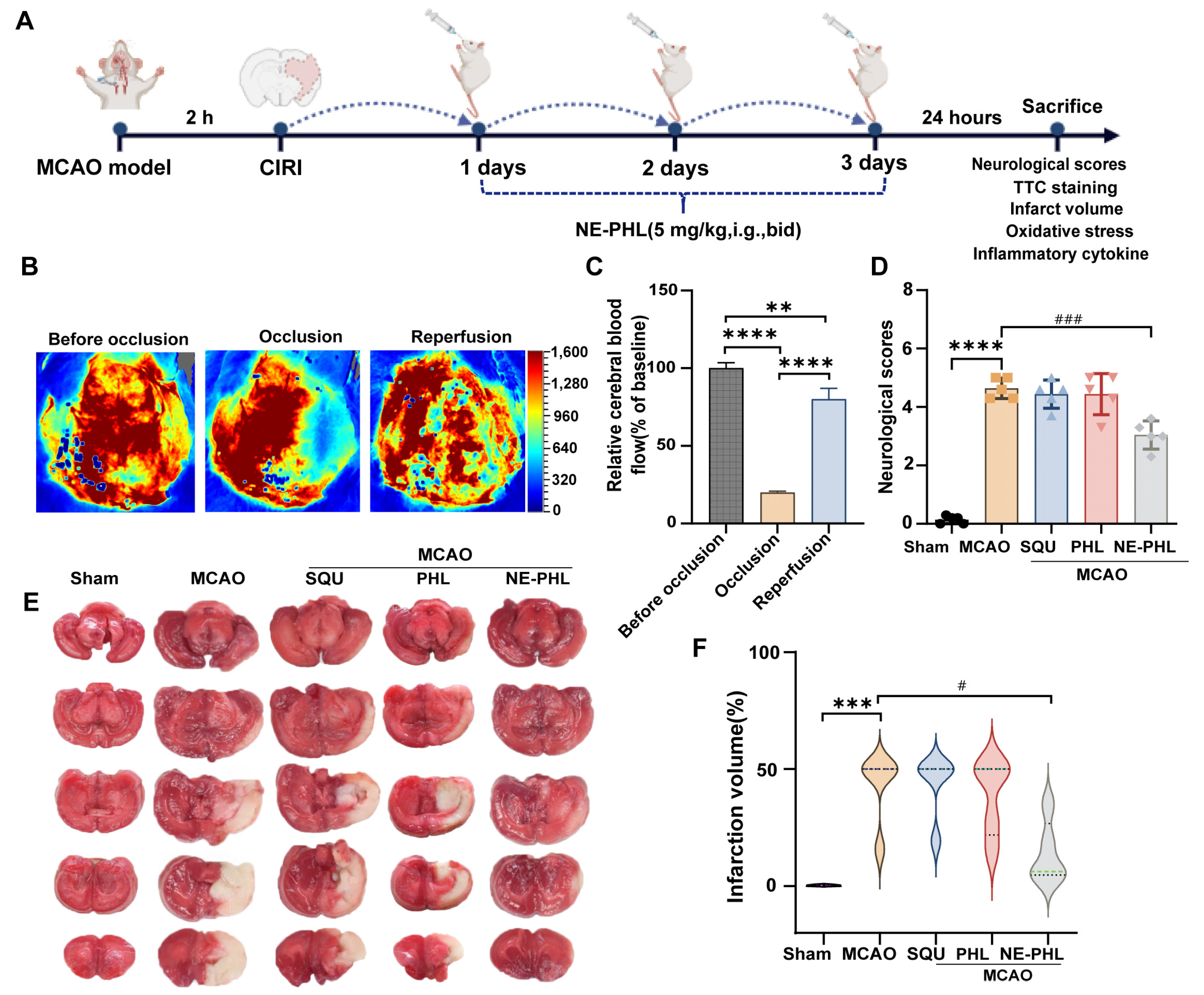

3.5. Pharmacodynamic Study

3.5.1. NE-PHL Alleviated Neurological Dysfunction in CIRI Rats

3.5.2. NE-PHL Decreased the Infarct Volume in CIRI Rats

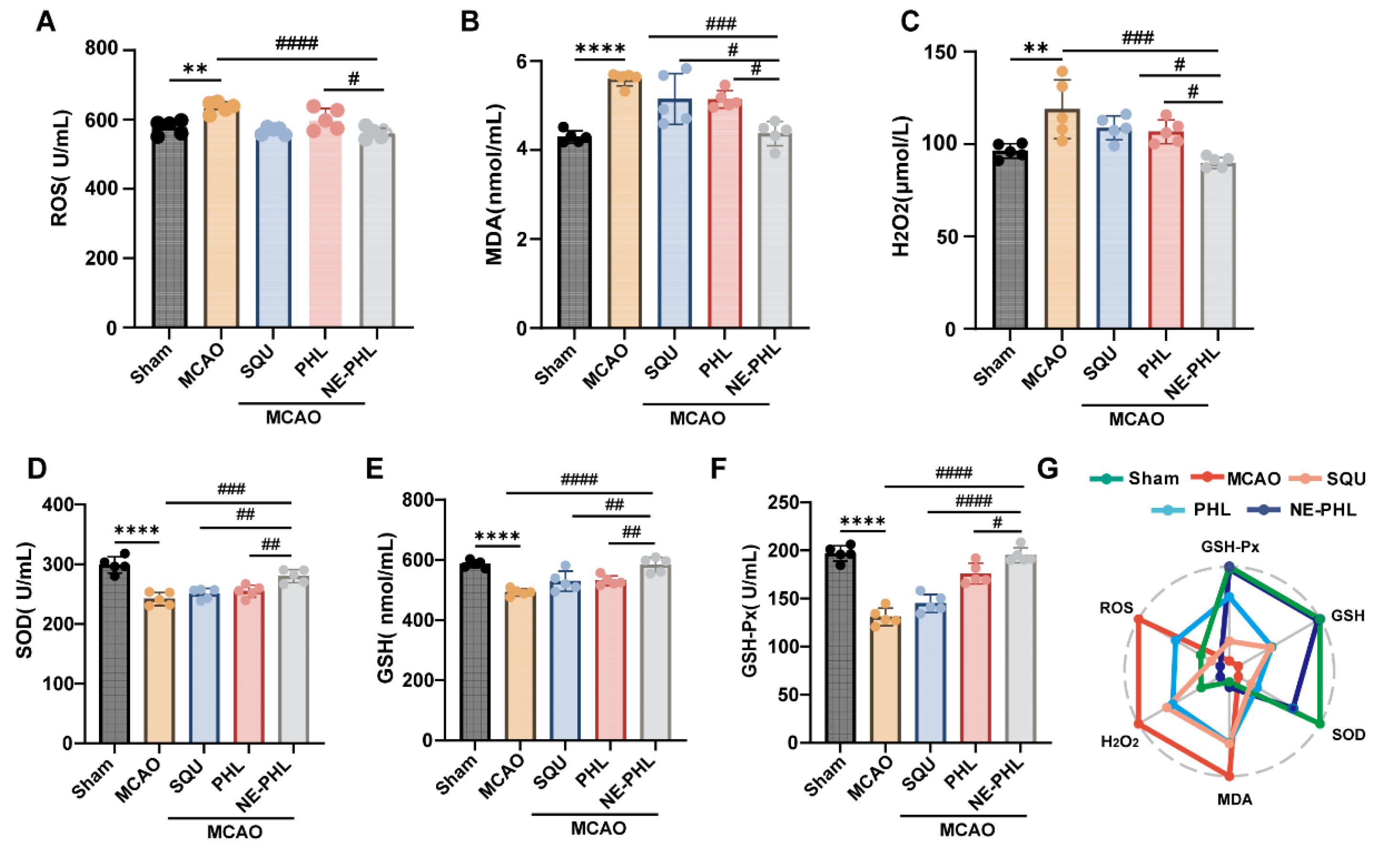

3.5.3. NE-PHL Attenuated the MCAO-Induced Oxidative Stress

3.5.4. NE-PHL Modulated Inflammatory Cytokine Release

3.6. RNA Sequencing Analysis of NE-PHL in CIRI Rats

3.7. In Vivo Biosafety of NE-PHL

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hilkens, N.A.; Casolla, B.; Leung, T.W.; de Leeuw, F.-E. Stroke. Lancet 2024, 403, 2820–2836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ju-Bin, K.; Phil-Ok, K. Retinoic Acid Has Neuroprotective effects by Modulating Thioredoxin in Ischemic Brain Damage and Glutamate-exposed Neurons. Neuroscience 2023, 521, 166–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCullough, L.D.; Roy-O’Reilly, M.; Lai, Y.J.; Patrizz, A.; Xu, Y.; Lee, J.; Holmes, A.; Kraushaar, D.C.; Chauhan, A.; Sansing, L.H.; et al. Exogenous inter-α inhibitor proteins prevent cell death and improve ischemic stroke outcomes in mice. J. Clin. Investig. 2021, 131, e144898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bei, Z.; Hai-Xiong, Z.; Shaoting, S.; Yulan, B.; Zhe, X.; Shijun, Z.; Yajun, L. Interleukin-11 treatment protected against cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2019, 115, 108816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, S.; Vanessa, K.; Bernhard, N. Platelets as Modulators of Cerebral Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 2505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vongsfak, J.; Pratchayasakul, W.; Apaijai, N.; Vaniyapong, T.; Chattipakorn, N.; Chattipakorn, S.C. The Alterations in Mitochondrial Dynamics Following Cerebral Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Fan, Y.; Peng, W. rTMS ameliorates cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury by inhibiting Golgi apparatus stress through epigenetic modulation of Gli2. Commun. Biol. 2025, 8, 1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Un, H.; Ugan, R.A.; Gurbuz, M.A.; Bayir, Y.; Kahramanlar, A.; Kaya, G.; Cadirci, E.; Halici, Z. Phloretin and phloridzin guard against cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity in mice through inhibiting oxidative stress and inflammation. Life Sci. 2021, 266, 118869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Peng, M.; Zang, J.; Han, S.; Li, P.; Guo, S.; Maiorano, G.; Hu, Q.; Hou, Y.; Yi, D. Phloretin supplementation ameliorates intestinal injury of broilers with necrotic enteritis by alleviating inflammation, enhancing antioxidant capacity, regulating intestinal microbiota, and producing plant secondary metabolites. Poult. Sci. 2025, 104, 105187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhimwal, J.; Goel, A.; Sukapaka, M.; Patial, V.; Padwad, Y. Phloretin mitigates oxidative injury, inflammation, and fibrogenic responses via restoration of autophagic flux in in vitro and preclinical models of NAFLD. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2022, 107, 109062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Liang, J. Activation of the Nrf2 defense pathway contributes to neuroprotective effects of phloretin on oxidative stress injury after cerebral ischemia/reperfusion in rats. J. Neurol. Sci. 2015, 351, 88–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreas, Ü.; Günter, F.; Eva, B.; Christoph, N.; Helga, R.; Hans Jörg, L.; Ernst, M.; Wolfgang, S. Phloretin ameliorates 2-chlorohexadecanal-mediated brain microvascular endothelial cell dysfunction in vitro. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2012, 53, 1770–1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iskandar, F.A.; Alena, R.; Gary, P.S.; Harold, K.K.; Alexander, A.M. Pharmacological comparison of swelling-activated excitatory amino acid release and Cl− currents in cultured rat astrocytes. J. Physiol. 2006, 572, 667–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakhate, K.T.; Badwaik, H.; Choudhary, R.; Sakure, K.; Agrawal, Y.O.; Sharma, C.; Ojha, S.; Goyal, S.N. Therapeutic Potential and Pharmaceutical Development of a Multitargeted Flavonoid Phloretin. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.Y.; Fan, Y.; Wang, M.; Wang, J.; Cheng, J.X.; Zou, J.B.; Zhang, X.F.; Shi, Y.J.; Guo, D.Y. Studies on pharmacokinetic properties and absorption mechanism of phloretin: In vivo and in vitro. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2020, 132, 110809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Londzin, P.; Siudak, S.; Cegieła, U.; Pytlik, M.; Janas, A.; Waligóra, A.; Folwarczna, J. Phloridzin, an Apple Polyphenol, Exerted Unfavorable Effects on Bone and Muscle in an Experimental Model of Type 2 Diabetes in Rats. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzidaki, M.D.; Mitsou, E. Advancements in Nanoemulsion-Based Drug Delivery Across Different Administration Routes. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, Y.; Meher, J.G.; Raval, K.; Khan, F.A.; Chaurasia, M.; Jain, N.K.; Chourasia, M.K. Nanoemulsion: Concepts, development and applications in drug delivery. J. Control. Release 2017, 252, 28–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.; Teng, W.; Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Cao, J. Polyglycerol polyricinoleate and lecithin stabilized water in oil nanoemulsions for sugaring Beijing roast duck: Preparation, stability mechanisms and color improvement. Food Chem. 2024, 447, 138979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocchio, J.; Neilsen, J.; Everett, K.; Bothun, G.D. A solvent-free lecithin-Tween 80 system for oil dispersion. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2017, 533, 218–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymczyk, K.; Jańczuk, B. Adsorption and volumetric properties of berberine and its mixtures with nonionic surfactants of the Kolliphor type. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2025, 346, 103662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiner, V.; Öhlinger, K.; Corzo, C.; Salar-Behzadi, S.; Fröhlich, E. Cytotoxicity screening of emulsifiers for pulmonary application of lipid nanoparticles. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2019, 136, 104968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löw, N.; Schneider, C.; Zegota, M.M.; Grabarek, A.; Corradini, E.; Schuster, G.; Roskamp, M.M.; Guth, F.; Hawe, A.; Kellermeier, M. Physicochemical Comparison of Kolliphor HS 15, ELP, and Conventional Surfactants for Antibody Stabilization in Biopharmaceutical Formulations. Mol. Pharm. 2025, 22, 4890–4908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chae, G.E.; Kim, D.W.; Jin, H.E. Development of Squalene-Based Oil-in-Water Emulsion Adjuvants Using a Self-Emulsifying Drug Delivery System for Enhanced Antigen-Specific Antibody Titers. Int. J. Nanomed. 2022, 17, 6221–6231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fox, C.B. Squalene emulsions for parenteral vaccine and drug delivery. Molecules 2009, 14, 3286–3312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, H.; Kim, T.W.; Kwon, M.; Kwon, I.C.; Jeong, S.Y. Oil components modulate physical characteristics and function of the natural oil emulsions as drug or gene delivery system. J. Control. Release 2001, 71, 339–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, T.J. Squalene: Potential chemopreventive agent. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs 2000, 9, 1841–1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, L.; Geng, S.; Zhou, Y.; Ma, H.; Liu, B. Ultrasound-assisted fabrication and stability evaluation of okra seed protein stabilized nanoemulsion. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2024, 104, 106807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, H.; Liu, Y.; Yu, Y.; Lv, D.; Ma, S.; Gao, M.; Yang, Y.; Yuan, C.; Liu, Y.; Wang, C. Panax notoginseng saponins and acetylsalicylic acid co-delivered liposomes for targeted treatment of ischemic stroke. Int. J. Pharm. 2024, 667, 124782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Xia, J.; Hu, Q.; Xu, L.; Cao, H.; Wang, X.; Cao, M. Long non-coding RNA XIST promotes cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury by modulating miR-27a-3p/FOXO3 signaling. Mol. Med. Rep. 2021, 24, 566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, S.; Kather, F.S.; Boddu, S.H.S.; Shah, J.; Nair, A.B. Innovations in Nanoemulsion Technology: Enhancing Drug Delivery for Oral, Parenteral, and Ophthalmic Applications. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nazari-Vanani, R.; Moezi, L.; Heli, H. In vivo evaluation of a self-nanoemulsifying drug delivery system for curcumin. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2017, 88, 715–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Ma, X.; Chen, Y. Advanced Insights of Oxidative Stress in Ischemic Stroke: Pathogenesis, Diagnosis and Treatment. In Neurological Problems in the Elderly—Bridging Current State and New Outlooks; Bozzetto Ambrosi, P., Ed.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Zhang, X.; Zhuang, D.; Dong, L.; Li, B. Mn2+-coordinated hyaluronic acid modified nanoparticles for phloretin delivery: Breast cancer treatment. Colloid Interface Sci. Commun. 2025, 68, 100854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Bal, T.; Singh, S.K.; Sharma, N. Biodegradable polymeric nanocomposite containing phloretin for enhanced oral bioavailability and improved myocardial ischaemic recovery. J. Microencapsul. 2024, 41, 754–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, T.; Gong, M.; Wang, X.; Hua, Q.; Jiang, X.; Wang, Q.; Toreniyazov, E.; Yu, J.; Cao, X.; et al. Preparation, in vitro and in vivo evaluation of phloretin-loaded TPGS/Pluronic F68 modified mixed micelles with enhanced bioavailability and anti-ageing activity. J. Drug Target. 2025, 33, 1167–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhimwal, J.; Dhritlahre, R.K.; Anand, P.; Ruchika; Patial, V.; Saneja, A.; Padwad, Y.S. Amorphous solid dispersion augments the bioavailability of phloretin and its therapeutic efficacy via targeting mTOR/SREBP-1c axis in NAFLD mice. Biomater. Adv. 2023, 154, 213627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, F.; Ru, X.; Wen, T. NRF2, a Transcription Factor for Stress Response and Beyond. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 4777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dierckx, T.; Haidar, M.; Grajchen, E.; Wouters, E.; Vanherle, S.; Loix, M.; Boeykens, A.; Bylemans, D.; Hardonnière, K.; Kerdine-Römer, S.; et al. Phloretin suppresses neuroinflammation by autophagy-mediated Nrf2 activation in macrophages. J. Neuroinflamm. 2021, 18, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.Y.; Zeng, Y.Y.; Ye, Y.X.; Zhou, Y.Y.; Mu, J.J.; Zhao, X.H. Anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive effect of phloretin. Acta Pharm. Sin. 2009, 44, 480–485. [Google Scholar]

| Formulation | Factor | Particle Size (nm) | PDI | Zeta (mV) | EE% | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | |||||

| F1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 96.69 | 0.046 | −35.42 | 78.36 |

| F2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 114.13 | 0.530 | −42.31 | 82.38 |

| F3 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 96.04 | 0.210 | −33.14 | / |

| F4 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 55.48 | 0.233 | −33.93 | 84.02 |

| F5 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 68.93 | 0.260 | −35.31 | 78.51 |

| F6 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 66.84 | 0.330 | −22.12 | 85.22 |

| F7 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 86.21 | 0.193 | −33.00 | / |

| F8 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 126.27 | 0.230 | −36.34 | / |

| F9 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 17.43 | 0.227 | −18.00 | / |

| K1 | 102.29 | 79.46 | 96.60 | ||||

| K2 | 63.75 | 103.11 | 62.35 | ||||

| K3 | 76.64 | 60.10 | 83.73 | ||||

| R | 38.54 | 43.01 | 34.25 | ||||

| Pharmacokinetic Parameters | PHL (100 mg·kg−1) | NE-PHL (100 mg·kg−1) |

|---|---|---|

| AUC 0–12 h (h × ng/mL) | 686.50 ± 198.19 | 1867.84 ± 692.02 * |

| AUC 0–∞ (h × ng/mL) | 761.63 ± 191.83 | 2033.383 ± 726.77 ** |

| MRT (0–12 h) (h) | 3.10 ± 1.09 | 4.20 ± 1.01 |

| MRT (0–∞) (h) | 4.77 ± 1.69 | 5.282 ± 2.157 |

| t1/2z (h) | 2.02 ± 0.88 | 2.60 ± 1.31 |

| T max (h) | 1.37 ± 1.54 | 1.87 ± 1.70 |

| CLz/F (L/h/kg) | 2.40 ± 50.88 | 0.90 ± 16.92 ** |

| Cmax (ng/mL) | 302.09 ± 144.25 | 581.28 ± 401.86 |

| F | 100% | 272.08% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Huang, T.; Wu, C.; Lu, W.; Lv, H.; Jin, R.; Gan, J.; Zhang, Y. Therapeutic Delivery of Phloretin by Mixed Emulsifier-Stabilized Nanoemulsion Alleviated Cerebral Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 1599. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17121599

Huang T, Wu C, Lu W, Lv H, Jin R, Gan J, Zhang Y. Therapeutic Delivery of Phloretin by Mixed Emulsifier-Stabilized Nanoemulsion Alleviated Cerebral Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury. Pharmaceutics. 2025; 17(12):1599. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17121599

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuang, Tingting, Changjing Wu, Wenchai Lu, Houbo Lv, Ronghui Jin, Jingyao Gan, and Yuandong Zhang. 2025. "Therapeutic Delivery of Phloretin by Mixed Emulsifier-Stabilized Nanoemulsion Alleviated Cerebral Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury" Pharmaceutics 17, no. 12: 1599. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17121599

APA StyleHuang, T., Wu, C., Lu, W., Lv, H., Jin, R., Gan, J., & Zhang, Y. (2025). Therapeutic Delivery of Phloretin by Mixed Emulsifier-Stabilized Nanoemulsion Alleviated Cerebral Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury. Pharmaceutics, 17(12), 1599. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17121599