Electronic Nursing Records: Importance for Nursing and Benefits of Implementation in Health Information Systems—A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

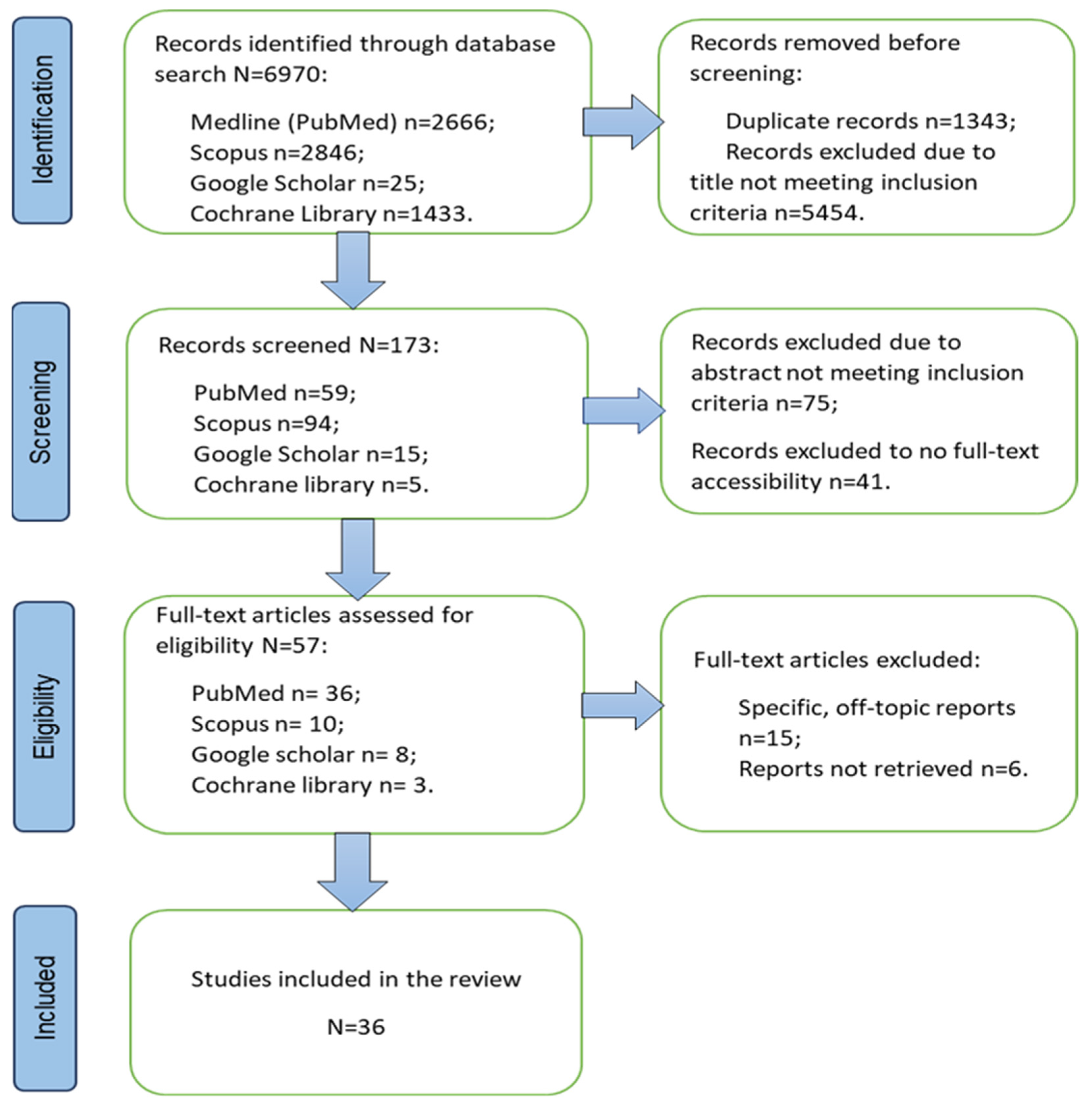

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

- -

- Inclusion criteria: Articles in both English and Spanish were included in the study, identified by the researchers as the most utilized languages in medical literature worldwide. The timeframe was constrained to the last 20 years (2004–2024), a decision justified by the advancements in information technologies and their application in healthcare. This conclusion was drawn from preliminary data extraction, in which the average publication time of sources relevant to similar topics was calculated. There were no restrictions based on the type of study; articles were considered irrespective of the research methodologies employed. Additionally, specific inclusion criteria were defined for secondary analysis, focusing on the impact of electronic nursing records (ENRs) on healthcare quality, on the knowledge and skills of nurses, and on the effectiveness of the nursing process. In the subsequent stage, filters were applied to allow access only to articles that were available in full text and offered free of charge.

- -

- Exclusion criteria: languages other than English and Spanish; publications before 2004.

2.2. Data Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Ability to Work with Standardized Nursing Information Regarding Nursing Classifications

4.2. Improving Health Management, Increasing the Quality of Care and Reducing the Risk of Errors

4.3. ENRs as a Prerequisite for Scientific Research

4.4. Impact of Electronic Records on the Behavior, Attitudes, and Knowledge of Medical Professionals/Students

4.5. Automation and Optimization of Processes

4.6. Conditions for Implementation of Electronic Nursing Documentation

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Public Involvement Statement

Guidelines and Standards Statement

Use of Artificial Intelligence

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mateos-Garcia, M.D. Implementación y evaluación de la documentación enfermera en la historia digital: Experiencia en el hospital Virgen de Valme. In Proceedings of the X Simposium AENTDE “Lenguaje Enfermero: Identidad, Utilidad y Calidad”, Sevilla, Spain, 3–4 April 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Rita-Vizoso, R. Cambios en la Practica Asistencial Tras la Adopción del Modelo de Virginia Henderson. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de A Coruña, A Coruña, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Rubio Sevilla, J.C.; Arribas Espada, J.L. Manual Básico del Programa Gacela. Complejo Hospitalario de Toledo. Direccion de Enfermeria. Available online: https://studylib.es/doc/3284092/manual-b%C3%A1sico-para-el-uso-del-programa-gacela (accessed on 15 September 2024).

- Sanchez Ros, N.; Regiosa Gago, L.F. Selene. Informatizacion de la historia clínica electrónica: Implicación sobre el proceso de enfermeria. Enferm. Glob. 2006, 5, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Sousa, E.C.V.; Lopes, V.O.M.; Fereira, L.G.; Diniz, M.C.; Froes, B.M.N.; Sobreira, A.B. The construction and evaluation of new educational software for nursing diagnoses: A randomized controlled trial. Nurse Educ. Today 2016, 36, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fennely, O.; Grogan, L.; Reed, A.; Hardiker, N.R. Use of standardized terminologies in clinical practice: A scoping review. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2021, 149, 104431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atanasova, V. Electronic Nursing Record. Manag. Educ. 2012, 8, 190–196. [Google Scholar]

- Grove, S.K.; Gray, J.R. Investigacion en Enfermeria: Desarrollo de la Practica Enfermera Basada en la Evidencia, 7th ed.; Elsevier: Barcelona, Spain, 2008; pp. 6–11. [Google Scholar]

- Halloran, E.J. Virginia Henderson and her timeless writings. J. Adv. Nurs. 1996, 23, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra, M.L.; Ruiz, S.S.; Rueda, G.S.; Porras, M.D.B.; Donaire, L.F.; Yarnoz, A.Z.; Sabater, D.A.; Peláez, S.V.; Sábado, J.T. Los modelos en la practica asistencial: Visión de los profesionales y estudiantes de enfermeria. Metas Enferm. 2009, 4, 16–26. [Google Scholar]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping Studies: Towards a Methodological Framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H.; McInerney, P.; Parker, D.; Soares, C.B. Guidance for Conducting Systematic Scoping Reviews. Int. J. Evid. Based Healthc. 2015, 13, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffman, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. Declaración PRISMA 2020: Una Guía Actualizada Para La Publicación de revisiones Sistemáticas. Rev. Esp. Cardiol. 2021, 74, 790–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngusie, H.S.; Kassie, S.Y.; Zemariam, A.B.; Walle, A.D.; Enyew, E.B.; Kasaye, M.D.; Seboka, B.T.; Mengiste, S.A. Understanding the predictors of health professionals’ intention to use electronic health record system: Extend and apply UTAUT3 model. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2024, 24, 889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Quan, Y.Y.; Chen, J. Construction and application of an ICU nursing electronic medical record quality control system in a Chinese tertiary hospital: A prospective controlled trial. BMC Nurs. 2024, 23, 493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hannah, K.J.; White, P.A.; Nagle, L.M.; Pringle, D.M. Standardizing nursing information in Canada for inclusion in electronic health records: C-HOBIC. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2009, 16, 524–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heidarizadeh, K.; Rassouli, M.; Manoochehri, H.; Tafreshi, M.Z.; Ghorbanpour, R.K. Effect of electronic report writing on the quality of nursing report recording. Electron. Physician 2017, 9, 5439–5445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahn, M.; Choi, M.; Kim, Y. Factors Associated with the Timeliness of Electronic Nursing Documentation. Healthc. Inform. Res. 2016, 22, 270–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevenson, J.E.; Nilsson, G.C.; Petersson, G.I.; Johansson, P.E. Nurses’ experience of using electronic patient records in everyday practice in acute/inpatient ward settings: A literature review. Health Inform. J. 2010, 16, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, A.F.; de Oliveira Melo, T. Percepção de enfermeiros em relação à implementação da informatização da documentação clínica de enfermagem [Nurses’ perception regarding the implementation of computer-based clinical nursing documentation]. Rev. Esc. Enferm. USP 2012, 46, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meum, T.; Wangensteen, G.; Soleng, K.S.; Wynn, R. How does nursing staff perceive the use of electronic handover reports? A questionnaire-based study. Int. J. Telemed. Appl. 2011, 2011, 505426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyun, S.; Johnson, S.B.; Stetson, P.D.; Bakken, S. Development and evaluation of nursing user interface screens using multiple methods. J. Biomed. Inform. 2009, 42, 1004–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, Y.H.; Park, H.A.; Chung, E.; Lee, H. Implementation of a next-generation electronic nursing records system based on detailed clinical models and integration of clinical practice guidelines. Healthc. Inform. Res. 2013, 19, 301–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouleau, G.; Gagnon, M.; Côté, J.; Payne-Gagnon, J.; Hudson, E.; Dubois, C. Impact of information and communication technologies on nursing care: Results of an overview of systematic reviews. J. Med. Internet Res. 2017, 19, e122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laukvik, L.B.; Lyngstad, M.; Rotegård, A.K.; Fossum, M. Utilizing nursing standards in electronic health records: A descriptive qualitative study. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2024, 184, 105350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naamneh, R.; Bodas, M. The effect of electronic medical records on medication errors, workload, and medical information availability among qualified nurses in Israel—A cross sectional study. BMC Nurs. 2024, 23, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irwin, P.; Hanson, M.; McDonald, S.; Noble, D.; Mollart, L. Nursing students’ perspectives on being work-ready with electronic medical records: Intersections of rurality and health workforce capacity. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2024, 77, 103948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jayousi, S.; Barchielli, C.; Alaimo, M.; Caputo, S.; Paffetti, M.; Zoppi, P.; Mucchi, L. ICT in nursing and patient healthcare management: Scoping review and case studies. Sensors 2024, 24, 3129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luan, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Gao, Y.; Du, S.; Wu, N.; Chen, Y.; Peng, X. Electronic health records in nursing from 2000 to 2020: A bibliometric analysis. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1049411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dionisi, S.; Di Simone, E.; Alicastro, G.M.; Angelini, S.; Giannetta, N.; Iacorossi, L.; Di Muzio, M. Nursing Summary: Designing a nursing section in the Electronic Health Record. Acta Biomed. 2019, 90, 293–299. [Google Scholar]

- Poissant, L.; Pereira, J.; Tamblyn, R.; Kawasumi, Y. The impact of electronic health records on time efficiency of physicians and nurses: A systematic review. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2005, 12, 505–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.M.; Huang, E.W.; Hou, I.C.; Liu, H.Y.; Li, F.S.; Chiou, S.F. Using a text mining approach to explore the recording quality of a nursing record system. J. Nurs. Res. 2019, 27, e27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topaz, M.; Ronquillo, C.; Peltonen, L.M.; Pruinelli, L.; Sarmiento, R.F.; Badger, M.K.; Ali, S.; Lewis, A.; Georgsson, M.; Jeon, E.; et al. Nurse informaticians report low satisfaction and multi-level concerns with electronic health records: Results from an international survey. AMIA Annu. Symp. Proc. 2017, 2016, 2016–2025. [Google Scholar]

- Kleib, M.; Jackman, D.; Duarte Wisnesky, U.; Ali, S. Academic electronic health records in undergraduate nursing education: Mixed methods pilot study. JMIR Nurs. 2021, 4, e26944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjarnadottir, R.I.; Herzig, C.T.A.; Travers, J.L.; Castle, N.G.; Stone, P.W. Implementation of electronic health records in US nursing homes. Comput. Inform. Nurs. 2017, 35, 417–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drnovšek, R.; Milavec Kapun, M.; Rajkovič, V.; Rajkovič, U. Analysis of two diverse nursing records applications: Mixed methods approach. Zdr. Varst. 2022, 61, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shafiee, M.; Shanbehzadeh, M.; Nassari, Z.; Kazemi-Arpanahi, H. Development and evaluation of an electronic nursing documentation system. BMC Nurs. 2022, 21, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goossen, W.T.; Ozbolt, J.G.; Coenen, A.; Park, H.A.; Mead, C.; Ehnfors, M.; Marin, H.F. Development of a provisional domain model for the nursing process for use within the Health Level 7 reference information model. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2004, 11, 186–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Wynn, M.; Garwood-Cross, L.; Vasilica, C.; Griffiths, M.; Heaslip, V.; Phillips, N. Digitizing nursing: A theoretical and holistic exploration to understand the adoption and use of digital technologies by nurses. J. Adv. Nurs. 2023, 79, 3737–3747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaihlanen, A.M.; Elovainio, M.; Virtanen, L.; Kinnunen, U.M.; Vehko, T.; Saranto, K.; Heponiemi, T. Nursing informatics competence profiles and perceptions of health information system usefulness among registered nurses: A latent profile analysis. J. Adv. Nurs. 2023, 79, 4022–4033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrasheeday, A.M.; Alshammari, B.; Alkubati, S.A.; Pasay-an, E.; Albloushi, M.; Alshammari, A.M. Nurses’ attitudes and factors affecting use of electronic health record in Saudi Arabia. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Aubaidy, H.F.K.; Abdulwahhab, M.M. Assessment of nurses’ knowledge toward electronic nursing documentation. Rawal Med. J. 2023, 48, 88–91. [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd, S.; Long, K.; Probst, Y.; Di Donato, J.; Alvandi, A.O.; Roach, J.; Bain, C. Medical and nursing clinician perspectives on the usability of the hospital electronic medical record: A qualitative analysis. Health Inf. Manag. 2023, 53, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strudwick, G.; Jeffs, L.; Kemp, J.; Sequeira, L.; Lo, B.; Shen, N.; Paterson, P.; Coombe, N.; Yang, L.; Ronald, K.; et al. Identifying and adapting interventions to reduce documentation burden and improve nurses’ efficiency in using electronic health record systems (The IDEA Study): Protocol for a mixed methods study. BMC Nurs. 2022, 21, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasso, G.; Barra, D.; Paese, F.; Almeida, S.; Rios, G.; Marinho, M.; Debétio, M. Computerized nursing process: Methodology to establish associations between clinical assessment, diagnosis, interventions, and outcomes. Rev. Esc. Enferm. USP 2013, 47, 242–249. [Google Scholar]

- Parvan, K.; Hosseini, F.A.; Jasemi, M.; Thomson, B. Attitude of nursing students following the implementation of comprehensive computer-based nursing process in medical surgical internship: A quasi-experimental study. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2021, 21, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westra, B.L.; Delaney, C.W.; Konicek, D.; Keenan, G. Nursing standards to support the electronic health record. Nurs. Outlook 2008, 56, 258–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westra, B.L.; Latimer, G.E.; Matney, S.A.; Park, J.I.; Sensmeier, J.; Simpson, R.L.; Swanson, M.J.; Warren, J.J.; Delaney, C.W. A national action plan for sharable and comparable nursing data to support practice and translational research for transforming health care. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2015, 22, 600–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller-Staub, M. Preparing nurses to use standardized nursing language in the electronic health record. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 2009, 146, 337–341. [Google Scholar]

- Inclusion of Recognized Terminologies Supporting Nursing Practice Within Electronic Health Records and Other Health Information Technology Solutions. Available online: https://www.nursingworld.org/practice-policy/nursing-excellence/official-position-statements/id/Inclusion-of-Recognized-Terminologies-Supporting-Nursing-Practice-within-Electronic-Health-Records/ (accessed on 15 September 2024).

- Zaman, N.; Goldberg, D.M.; Kelly, S.; Russell, R.S.; Drye, S.L. The relationship between nurses’ training and perceptions of electronic documentation systems. Nurs. Rep. 2021, 11, 12–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Database | Search Strategy | Search Date |

|---|---|---|

| Medline (PubMed) | (nursing records) OR (electronic health records) AND (nursing care) | 16 August 2024 |

| Scopus | (nursing records) OR (electronic health records) AND (nursing care) | 16 August 2024 |

| Google Scholar | nursing electronic records | 17 August 2024 |

| Cochrane Library | nursing AND electronic AND records | 17 August 2024 |

| Database | Authors/Title/Year | Country/ City | Type of Study | Research Focus | Main Results/Highlights | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | PubMed | Ngusie, H.S., Kassie, S.Y., Zemariam, A.B. et al. Understanding the predictors of health professionals’ intention to use electronic health record system: extend and apply UTAUT3 model. 2024 [14] | Ethiopia | Statistical qualitative | To reveal and understand predictors of healthcare professionals’ intention to use electronic health records (EHRs). | Readiness to use EHRs depends on personal initiative, motivation, fear of technology, and social variables with a distinct gender difference. |

| 2 | PubMed | Zhang, S., Quan, Y.Y. and Chen, J. Construction and application of an ICU nursing electronic medical record quality control system in a Chinese tertiary hospital: a prospective controlled trial. 2024 [15] | China | A prospective controlled study | Development and evaluation of an EHR quality control system in an emergency department targeting electronic nursing records (ENRs). | Electronic medical record quality control systems application increases efficiency, reduces the risk of errors, and ensures patient safety and quality of care. |

| 3 | PubMed | Hannah KJ, White PA, Nagle LM, Pringle DM. Standardizing nursing information in Canada for inclusion in electronic health records: C-HOBIC. 2009 [16] | Canada | - | Standardization of nursing information visualized in EHRs at the national level and trial of a system adapted to this. | The introduction of a specific ENR model within EHRs supports the standardization of nursing care and processes. It is well accepted by the users. |

| 4 | PubMed | Heidarizadeh K, Rassouli M, Manoochehri H, Tafreshi MZ, Ghorbanpour RK. Effect of electronic report writing on the quality of nursing report recording. 2017 [17] | Iran | A quasi-experimental study | Determining the effect of ENR use on the quality of nursing documentation. | The introduction of a standardized language for nursing records (in this case the Clinical Care Classification (CCC) system) leads to an increase in the quality of nursing records. |

| 5 | PubMed | Ahn M, Choi M, Kim Y. Factors Associated with the Timeliness of Electronic Nursing Documentation. 2016 [18] | South Korea | A retrospective quantitative study | A study of factors associated with timely entry of nursing information into EHRs. | The timeliness of data entry depends on the nurse’s experience, day of the week, and work shift. |

| 6 | PubMed | Stevenson JE, Nilsson GC, Petersson GI, Johansson PE. Nurses’ experience of using electronic patient records in everyday practice in acute/inpatient ward settings: A literature review. 2010 [19] | Sweden | Literature review | Research of nurses’ views on the use of EPRs. | The use of EHRs and BIS in many cases is not designed by/for nurses and they experience difficulties in entering information. |

| 7 | PubMed | Lima AF, de Oliveira Melo T. Percepção de enfermeiros em relação à implementação da informatização da documentação clínica de enfermagem [Nurses’ perceptions regarding the implementation of computer-based clinical nursing documentation]. 2012 [20] | Brazil | A descriptive qualitative study | An analysis of nurses’ perceptions of the implementation of computer-based clinical nursing documentation in surgical units. | Nurses support the module’s introduction due to training strategies and suggestion opportunities. |

| 8 | PubMed | Meum T, Wangensteen G, Soleng KS, Wynn R. How does nursing staff perceive the use of electronic handover reports? A questionnaire-based study. 2011 [21] | Norway | Analytical qualitative research | Assessing attitudes and perceptions about electronic nursing reporting in a university hospital. | Most of the working nurses are satisfied with the electronic reports. |

| 9 | PubMed | Hyun S, Johnson SB, Stetson PD, Bakken S. Development and evaluation of nursing user interface screens using multiple methods. 2009 [22] | USA, New York | - | Investigating nurses’ perceptions of ENR functionality and creating user interface screens. | The effectiveness of BIS and EHRs depends on their modeling to fulfill the needs of users. |

| 10 | PubMed | Min YH, Park HA, Chung E, Lee H. Implementation of a next-generation electronic nursing records system based on detailed clinical models and integration of clinical practice guidelines. 2013 [23] | South Korea | - | Defining the components of a next-generation ENR system providing full semantic interoperability and evidence integration into the nursing record system. | The results consist of the successful implementation of ENRs in a hospital in Seoul based on clinical models and clinical practice guidelines. It is a prerequisite for successfully maintaining nursing practice and documentation. |

| 11 | PubMed | Rouleau G, Gagnon M, Côté J, Payne-Gagnon J, Hudson E, Dubois C Impact of Information and Communication Technologies on Nursing Care: Results of an Overview of Systematic Reviews. 2017 [24] | Canada | Overview of systematic reviews | Analysis of dimensions and indicators of nursing care potentially influenced by information technology. | There are aspects of the nursing process that are affected by various information and communication technologies and can be optimized. |

| 12 | PubMed | Laukvik LB, Lyngstad M, Rotegård AK, Fossum M. Utilizing nursing standards in electronic health records: A descriptive qualitative study. 2024 [25] | Norway | A descriptive qualitative study | Analysis of the experience and the perceptions of nurses, working in nursing homes regarding ENR use and standardized taxonomy. | ENR knowledge and skills affect the quality of records; the organization of ENRs influences the motivation to work; usability issues impede normal workflow; ENR standardization leads to improved practice and advances nursing knowledge. |

| 13 | PubMed | Naamneh, R., Bodas, M. The effect of electronic medical records on medication errors, workload, and medical information availability among qualified nurses in Israel—a cross sectional study. 2024 [26] | Izrael | A descriptive cross-sectional study | Research of the position of medical staff regarding the impact of EMR systems on factors related to patient safety, including medication errors, workload, and availability of medical information. | The results indicate a positive attitude towards EHRs regarding safety enhancement but indicate deficiencies regarding the ability to input the information. |

| 14 | PubMed | Irwin P, Hanson M, McDonald S, Noble D, Mollart L. Nursing students’ perspectives on being work-ready with electronic medical records: Intersections of rurality and health workforce capacity. 2024 [27] | Australia | Online survey/qualitative research | A survey of student nurses’ views on preparedness for EHR use. | Students feel more confident using EHRs during their training process and consider it necessary to introduce simulation programs for better clinical work after graduation. |

| 15 | PubMed | Jayousi S, Barchielli C, Alaimo M, Caputo S, Paffetti M, Zoppi P, Mucchi L. ICT in Nursing and Patient Healthcare Management: Scoping Review and Case Studies. 2024 [28] | Italy | Scoping review/case studies | Exploration of a wide range of information and communication technologies used in nursing and healthcare. | This article highlights how these technologies have improved the efficiency, accuracy, and accessibility of clinical information, contributing to improved patient care, safety, satisfaction, and management. |

| 16 | PubMed | Luan Z, Zhang Z, Gao Y, Du S et al. Electronic health records in nursing from 2000 to 2020: a bibliometric analysis. 2023 [29] | China | Literature review | A survey of the application of EHRs in nursing and identification of the current research status quo on the subject. | Studies on the use of EHR in nursing are increasing every year. They are a prerequisite for the development of collaboration and research trends to improve the use of information and communication technologies. |

| 17 | PubMed | Dionisi S, Di Simone E, Alicastro GM, Angelini S, Giannetta N, Iacorossi L, Di Muzio M. Nursing Summary: designing a nursing section in the Electronic Health Record. 2019 [30] | Italy | Literature review | Analyzing the components required to include a nursing section in EHRs. | The introduction of EHRs within the framework of EHRs contributes to the multidisciplinary management of care, improvement of their quality, and expansion of health information and is a prerequisite for scientific research. |

| 18 | PubMed | Poissant L, Pereira J, Tamblyn R, Kawasumi Y. The impact of electronic health records on time efficiency of physicians and nurses: a systematic review. 2005 [31] | Canada | A systematic review | Investigation of the impact of EHRs on the times for physician and nurse documentation and identify factors that may explain differences in effectiveness between studies. | Time efficiency is a major factor in the successful implementation and use of EHRs. |

| 19 | PubMed | Chang HM, Huang EW, Hou IC, Liu HY, Li FS, Chiou SF. Using a Text Mining Approach to Explore the Recording Quality of a Nursing Record System. 2019 [32] | Taiwan | A retrospective quantitative study | Nursing record system quality analysis using SAS Text Miner software. | The software successfully identifies errors in the nursing record system and can be used as an audit system to assess the quality of nursing records. |

| 20 | PubMed | Topaz M, Ronquillo C, Peltonen LM, Pruinelli L, Sarmiento RF, Badger MK, Ali S, Lewis A, Georgsson M, Jeon E, Tayaben JL, Kuo CH, Islam T, Sommer J, Jung H, Eler GJ, Alhuwail D, Lee YL. Nurse Informaticians Report Low Satisfaction and Multi-level Concerns with Electronic Health Records: Results from an International Survey. 2017 [33] | International study | Descriptive cross-sectional | This study presents a qualitative analysis of nurses’ satisfaction and problems with current EHR systems. | The study reveals low satisfaction among nurses regarding the nursing functions in EHRs, and the identified factors for this are problems with the systems, lack of functionality, lack of nursing modules in EHRs, lack of user training, etc. |

| 21 | PubMed | Kleib M, Jackman D, Duarte Wisnesky U, Ali S. Academic Electronic Health Records in Undergraduate Nursing Education: Mixed Methods Pilot Study. 2021 [34] | Canada | Survey qualitative research | Preliminary evaluation of the Lippincott DocuCare simulated electronic health record and to determine the feasibility issues associated with its implementation. | Study participants support the nursing module and develop strategies and recommendations for its integration into baccalaureate nursing programs in western Canada. |

| 22 | PubMed | Bjarnadottir RI, Herzig CTA, Travers JL, Castle NG, Stone PW. Implementation of Electronic Health Records in US Nursing Homes. 2017 [35] | CAIII USA | A randomized cross-sectional study | Assessing the implementation of electronic health records (EHRs) in US nursing homes to determine the characteristics of introducing homes and assess their impact on service quality. | The adoption of EHRs in US nursing homes is moving at a slower pace than in active care hospital settings. However, research indicates that the quality of care has demonstrated improvement following the implementation of EHR systems. |

| 23 | PubMed | Drnovšek R, Milavec Kapun M, Rajkovič V, Rajkovič U. Analysis of Two Diverse Nursing Records Applications: Mixed Methods Approach. 2022 [36] | Slovenia | Mixed research (quantitative/qualitative) | A comparison of user experience and perceived quality of nursing process integration in two different electronic nursing care plan documentation applications. | Different results were found regarding elements of nursing care implemented in the two software applications; student perceptions were assessed. The limitation lies in the insufficient experience of the students and the resulting impossibility of objective assessment. |

| 24 | PubMed | Shafiee M, Shanbehzadeh M, Nassari Z, Kazemi-Arpanahi H. Development and evaluation of an electronic nursing documentation system. 2022 [37] | Iran | A four-step sequential methodological approach: literature review, Delphi analysis, module construction, evaluation of its use | Process description of the design and content evaluation of the electronic clinical nursing record system. | The minimum acceptable clinical information is entered into the ENR, which reduces the burden of paper documentation and increases user satisfaction. |

| 25 | PubMed | Goossen WT, Ozbolt JG, Coenen A, Park HA, Mead C, Ehnfors M, Marin HF. Development of a provisional domain model for the nursing process for use within the Health Level 7 reference information model. 2004 [38] | International study | - | Definition of standardized nursing terminology within the ENR for its inclusion in HIS with HL7. | It is possible to model and map nursing information into the overall healthcare information model. Integrating nursing information, terminology, and processes into information models is a first step toward making nursing information machine-readable in electronic patient records. |

| 26 | Scopus | Wynn M, Garwood-Cross L, Vasilica C, Griffiths M, Heaslip V, Phillips N. Digitizing nursing: A theoretical and holistic exploration to understand the adoption and use of digital technologies by nurses. 2023 [39] | UK | Literature review | Examining how key demographics such as gender, age, and voluntary technology use interact to influence nurses’ adoption and use of digital technologies. | Demographic and personality factors influence the integration of ENRs and suggest using individual strategies for success. A holistic approach is necessary to overcome barriers to change. |

| 27 | Scopus | Kaihlanen AM, Elovainio M, Virtanen L, Kinnunen UM, Vehko T, Saranto K, Heponiemi T. Nursing informatics competence profiles and perceptions of health information system usefulness among registered nurses: A latent profile analysis. 2023 [40] | Finland | Cross-sectional study | Investigating different profiles of nursing information competencies and their relationship to perceptions of the usefulness of HIS. | Different levels of competence have been identified, with technological competence directly proportional to the positive perception of the usefulness of HISs. Educational strategies for nurses are needed to improve digital health knowledge and skills. |

| 28 | Scopus | Alrasheeday AM, Alshammari B, Alkubati SA, Pasay-an E, Albloushi M, Alshammari AM. Nurses’ Attitudes and Factors Affecting Use of Electronic Health Record in Saudi Arabia. 2023 [41] | Saudi Arabia | Cross-sectional study | Assessment of nurses’ attitudes towards EHR and related factors influencing EHR implementation in different hospitals in Saudi Arabia. | Various factors have been identified that influence positive attitudes towards EHR: younger people, with a master’s degree, men and with prior computer experience. Involving nurses in decision-making processes and addressing their concerns can promote favorable attitudes toward EHR implementation. |

| 29 | Scopus | Al-Aubaidy, H.F.K.; Abdulwahhab, M.M. (2023). Assessment of nurses’ knowledge toward electronic nursing documentation. Assessment of nurses’ knowledge toward electronic nursing documentation. 2023 [42] | Iraq | A descriptive study | Assessment of nurses’ knowledge about ENR. | Knowledge of electronic nursing records in Iraq is unsatisfactory and unrelated to age, gender, or education level. |

| 30 | Scopus | Lloyd S, Long K, Probst Y. et al. Medical and nursing clinician perspectives on the usability of the hospital electronic medical record: A qualitative analysis. 2023 [43] | Australia | Qualitative research | Research of physicians’ and nurses’ opinions about EMR usability. | There is a positive attitude towards the possibility of access from any location, easy documentation of drug therapy, and the possibility of visualizing clinical and instrumental studies. Disadvantages reported are system complexity, difficult communication with primary care, and lack of time resources. |

| 31 | Scopus | Strudwick G, Jeffs L, Kemp J. et al. Identifying and adapting interventions to reduce documentation burden and improve nurses’ efficiency in using electronic health record systems (The IDEA Study): protocol for a mixed methods study. 2022 [44] | Canada | A three-phase mixed study | Engaging nurses to generate ideas for supporting and optimizing their experiences with ENR systems, improving efficiency, and reducing ENR-related burdens within organizations. | Understanding the key factors related to inefficiencies in ENRs and overcoming them will reduce the risk of documentation overload for nurses, and facilitate the discovery of methods to improve electronic documentation. |

| 32 | Scopus | Dal Sasso GT, Barra DC, Paese F, de Almeida SR, Rios GC, Marinho MM, Debétio MG. Computerized nursing process: methodology to establish associations between clinical assessment, diagnosis, interventions, and outcomes. 2013 [45] | Brazil | A three-stage methodological study | Making a connection between nursing assessment, diagnosis, interventions, and outcomes within ENRs in an emergency department and the ICNP International Classification System. | Standardizing nursing language and taxonomy, as well as establishing logical relationships through an international classification system, enhances nurses’ ability for clinical decision-making, reasoning, and interdisciplinary communication. |

| 33 | Google Scholar | Parvan K, Hosseini FA, Jasemi M. et al. Attitude of nursing students following the implementation of comprehensive computer-based nursing process in medical surgical internship: a quasi-experimental study. 2021 [46] | Iran | A quasi-experimental study. | Assessment of nursing students’ attitudes towards ENRs at the University of Tabriz. | Positive ratings for the software being tested have been reported in relation to the prioritization of care, completeness of electronic information, and time-saving. Negative feedback has been received regarding the software’s inability to account for fair distribution of labor and workload. |

| 34 | Google Scholar | Westra BL, Delaney CW, Konicek D, Keenan G. Nursing standards to support the electronic health record. 2008 [47] | USA | - | To determine the status and level of nursing standardized terminologies to support the development, exchange, and communication of nursing data. | The standardization of nursing terminology is increasingly important and directly related to the digitalization of health information. Standards in ENRs allow for embedding in EHR, result optimization, and improvement in quality. |

| 35 | Google Scholar | Westra BL, Latimer GE, Matney SA, Park JI. et al. A national action plan for sharable and comparable nursing data to support practice and translational research for transforming health care. 2015 [48] | USA | - | An inventory of the historical context of nursing terminologies, challenges in using nursing data for purposes other than documenting care, and a national action plan to implement and use shared and comparable nursing data for quality reporting and translation. | In the USA, a national plan has been implemented to define and integrate standard and shareable nursing data into the national health information system. This process has taken more than ten years and involves the experience and efforts of many organizations. |

| 36 | Cochrane library | Müller-Staub M. Preparing nurses to use standardized nursing language in the electronic health record. 2009 [49] | Switzerland | A cluster-randomized experimental trial | Exploring the effect of Guided Clinical Reasoning on the use of standardized nursing language. | A standardized taxonomy in ENRs helps define accurate nursing diagnoses, outcomes, and interventions. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Taneva, D.I.; Gyurova-Kancheva, V.T.; Kirkova-Bogdanova, A.G.; Paskaleva, D.A.; Zlatanova, Y.T. Electronic Nursing Records: Importance for Nursing and Benefits of Implementation in Health Information Systems—A Scoping Review. Nurs. Rep. 2024, 14, 3585-3605. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep14040262

Taneva DI, Gyurova-Kancheva VT, Kirkova-Bogdanova AG, Paskaleva DA, Zlatanova YT. Electronic Nursing Records: Importance for Nursing and Benefits of Implementation in Health Information Systems—A Scoping Review. Nursing Reports. 2024; 14(4):3585-3605. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep14040262

Chicago/Turabian StyleTaneva, Daniela Ivova, Vasilka Todorova Gyurova-Kancheva, Angelina Georgieva Kirkova-Bogdanova, Diana Angelova Paskaleva, and Yovka Tinkova Zlatanova. 2024. "Electronic Nursing Records: Importance for Nursing and Benefits of Implementation in Health Information Systems—A Scoping Review" Nursing Reports 14, no. 4: 3585-3605. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep14040262

APA StyleTaneva, D. I., Gyurova-Kancheva, V. T., Kirkova-Bogdanova, A. G., Paskaleva, D. A., & Zlatanova, Y. T. (2024). Electronic Nursing Records: Importance for Nursing and Benefits of Implementation in Health Information Systems—A Scoping Review. Nursing Reports, 14(4), 3585-3605. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep14040262