State-of-the-Art on Wound Vitality Evaluation: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

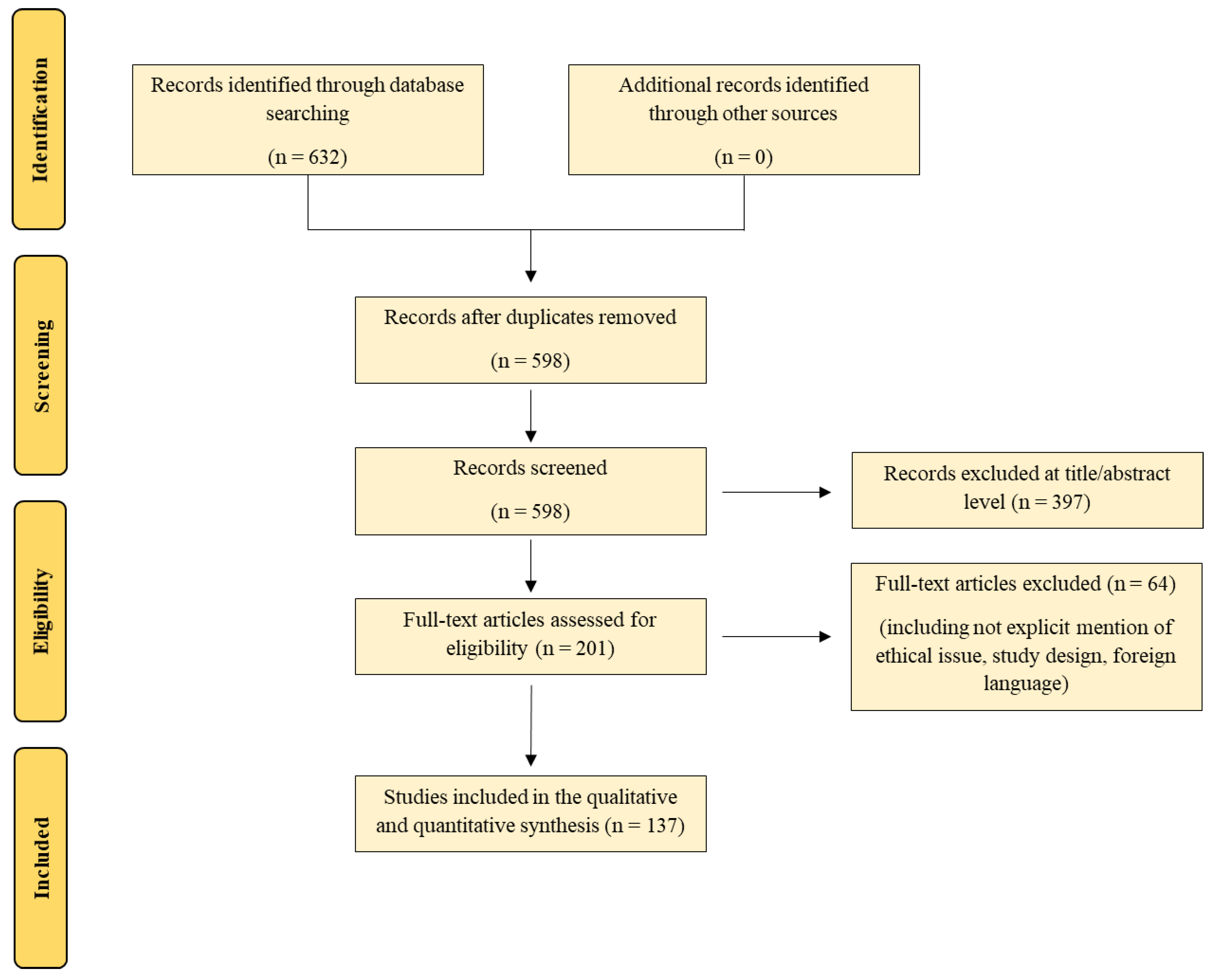

2. Materials and Methods

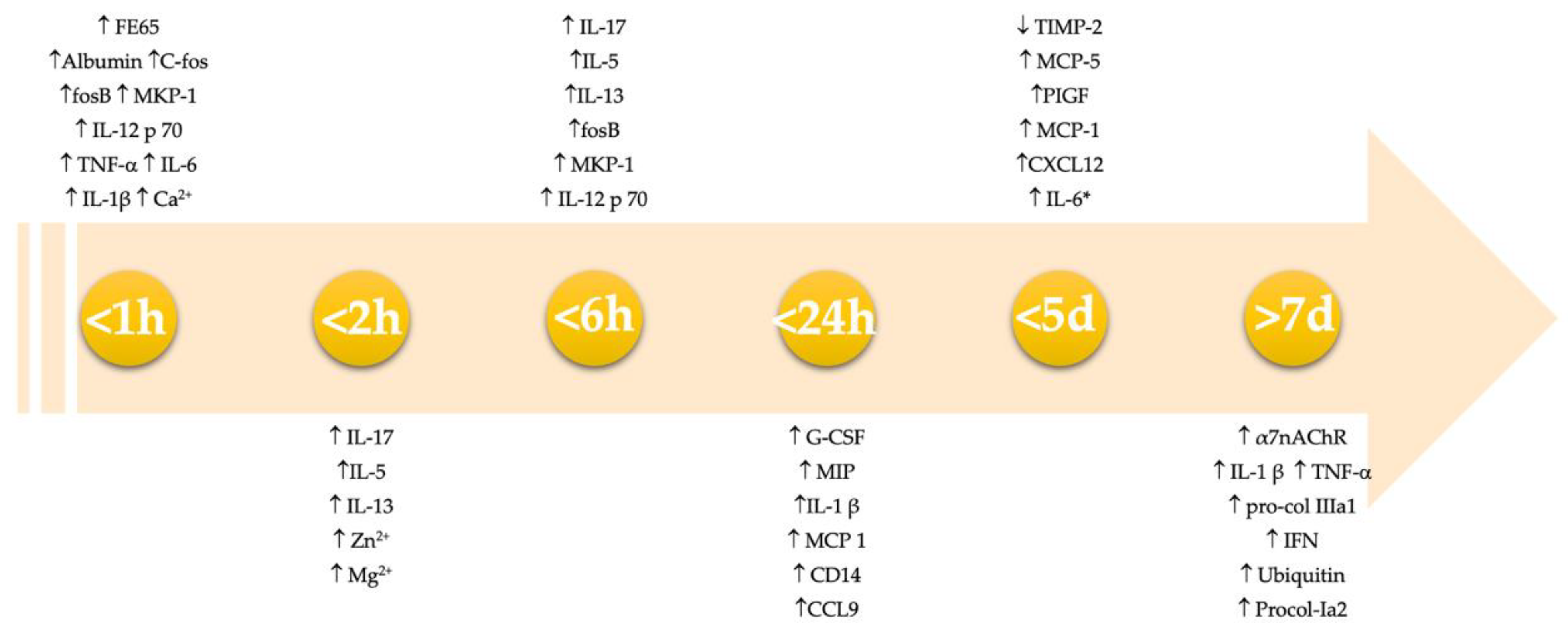

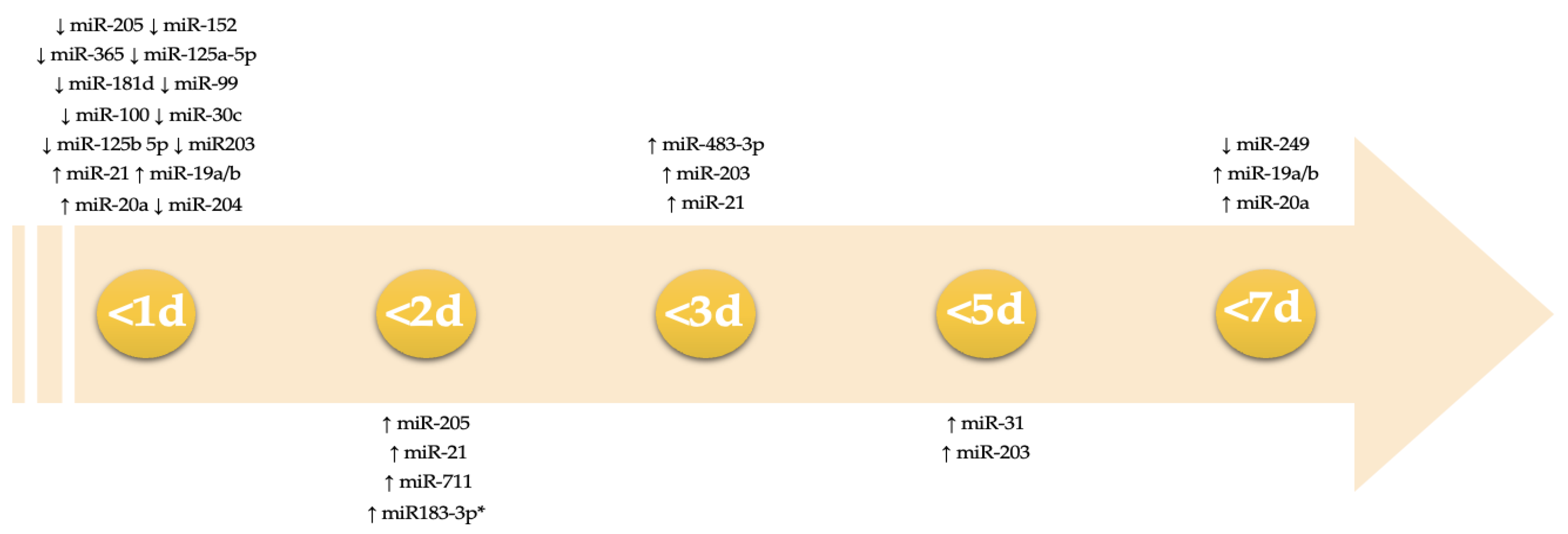

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Oehmichen, M. Vitality and time course of wounds. Forensic Sci. Int. 2004, 144, 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cappella, A.; Cattaneo, C. Exiting the limbo of perimortem trauma: A brief review of microscopic markers of hemorrhaging and early healing signs in bone. Forensic Sci. Int. 2019, 302, 109856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byard, R.W.; Wick, R.; Gilbert, J.D.; Donald, T. Histologic dating of bruises in moribund infants and young children. Forensic Sci. Med. Pathol. 2008, 4, 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balandiz, H.; Pehlivan, S.; Çiçek, A.F.; Tuğcu, H. Evaluation of Vitality in the Experimental Hanging Model of Rats by Using Immunohistochemical IL-1β Antibody Staining. Am. J. Forensic Med. Pathol. 2015, 36, 317–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turillazzi, E.; Vacchiano, G.; Luna-Maldonado, A.; Neri, M.; Pomara, C.; Rabozzi, R.; Riezzo, I.; Fineschi, V. Tryptase, CD15 and IL-15 as reliable markers for the determination of soft and hard ligature marks vitality. Histol. Histopathol. 2010, 25. [Google Scholar]

- Raekallio, J. Determination of the age of wounds by histochemical and biochemical methods. Forensic Sci. 1972, 1, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonelli, A.; Bacci, S.; Vannelli, G.; Norelli, G. Immunohistochemical localization of mast cells as a tool for the discrimination of vital and postmortem lesions. Int. J. Leg. Med. 2003, 117, 14–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishida, Y.; Kuninaka, Y.; Nosaka, M.; Shimada, E.; Hata, S.; Yamamoto, H.; Hashizume, Y.; Kimura, A.; Furukawa, F.; Kondo, T. Forensic application of epidermal AQP3 expression to determination of wound vitality in human compressed neck skin. Int. J. Leg. Med. 2018, 132, 1375–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansueto, G.; Feola, A.; Zangani, P.; Porzio, A.; Carfora, A.; Campobasso, C.P. A Clue on the Skin: A Systematic Review on Immunohistochemical Analyses of the Ligature Mark. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grellner, W. Time-dependent immunohistochemical detection of proinflammatory cytokines (IL-1beta, IL-6, TNF-alpha) in human skin wounds. Forensic Sci. Int. 2002, 130, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, L.; Zhu, B.-L.; Ishikawa, T.; Michiue, T.; Zhao, D.; Li, D.-R.; Ogawa, M.; Maeda, H. Postmortem serum erythropoietin levels in establishing the cause of death and survival time at medicolegal autopsy. Int. J. Leg. Med. 2008, 122, 481–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reichelt, U.; Jung, R.; Nierhaus, A.; Tsokos, M. Serial monitoring of interleukin-1beta, soluble interleukin-2 receptor and lipopolysaccharide binding protein levels after death A comparative evaluation of potential postmortem markers of sepsis. Int. J. Leg. Med. 2005, 119, 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hougen, H.P.; Valenzuela, A.; Lachica, E.; Villanueva, E. Sudden cardiac death: A comparative study of morphological, histochemical and biochemical methods. Forensic Sci. Int. 1992, 52, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manetti, A.C.; Maiese, A.; Baronti, A.; Mezzetti, E.; Frati, P.; Fineschi, V.; Turillazzi, E. MiRNAs as New Tools in Lesion Vitality Evaluation: A Systematic Review and Their Forensic Applications. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manetti, A.C.; Maiese, A.; Di Paolo, M.; De Matteis, A.; La Russa, R.; Turillazzi, E.; Frati, P.; Fineschi, V. MicroRNAs and Sepsis-Induced Cardiac Dysfunction: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 22, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinchi, E.; Frati, A.; Cantatore, S.; D’Errico, S.; La Russa, R.; Maiese, A.; Palmieri, M.; Pesce, A.; Viola, R.V.; Fineschi, V. Acute Spinal Cord Injury: A Systematic Review Investigating miRNA Families Involved. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubakov, D.; Boersma, A.W.M.; Choi, Y.; van Kuijk, P.F.; Wiemer, E.A.C.; Kayser, M. MicroRNA markers for forensic body fluid identification obtained from microarray screening and quantitative RT-PCR confirmation. Int. J. Leg. Med. 2010, 124, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oono, T.; Specks, U.; Eckes, B.; Majewski, S.; Hunzelmann, N.; Timpl, R.; Krieg, T. Expression of Type VI Collagen mRNA During Wound Healing. J. Investig. Dermatol. 1993, 100, 329–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: Explanation and elaboration. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2009, 62, e1–e34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, B.-L.; Ishida, K.; Quan, L.; Taniguchi, M.; Oritani, S.; Kamikodai, Y.; Fujita, M.Q.; Maeda, H. Post-mortem urinary myoglobin levels with reference to the causes of death. Forensic Sci. Int. 2001, 115, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, A.A.-R.; Elbohi, K.M.; El Sharkawy, N.I.; Hassan, M.A. Biochemical and Apoptotic Biomarkers of Experimentally Induced Traumatic Brain Injury: In Relation to Time since Death. Beni-Suef Univ. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobeissy, F.H.; Shakkour, Z.; Hayek, S.E.; Mohamed, W.; Gold, M.S.; Wang, K.K.W. Elevation of Pro-inflammatory and Anti-inflammatory Cytokines in Rat Serum after Acute Methamphetamine Treatment and Traumatic Brain Injury. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2022, 72, 158–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njau, S.N.; Epivatianos, P.; Tsoukali-Papadopoulou, H.; Psaroulis, D.; Stratis, J.A. Magnesium, calcium and zinc fluctuations on skin induced injuries in correlation with time of induction. Forensic Sci. Int. 1991, 50, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.C.; Hu, B.J.; Yao, Q.S.; Zhu, J.Z. Diagnostic value of ions as markers for differentiating antemortem from postmortem wounds. Forensic Sci. Int. 1995, 75, 157–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Zhu, J. Distinguishing antemortem from postmortem injuries by LTB4 quantification. Forensic Sci. Int. 1996, 81, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laiho, K. Peroxidase activity in traumatic skin lesions. Z. Rechtsmed. 1988, 100, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grellner, W.; Georg, T.; Wilske, J. Quantitative analysis of proinflammatory cytokines (IL-1beta, IL-6, TNF-alpha) in human skin wounds. Forensic Sci. Int. 2000, 113, 251–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laiho, K. Albumin as a marker of plasma transudation in experimental skin lesions. Int. J. Leg. Med. 2004, 118, 282–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, B.R.; Szelenyi, E.R.; Warren, G.L.; Urso, M.L. Alterations in mRNA and protein levels of metalloproteinases-2, -9, and -14 and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-2 responses to traumatic skeletal muscle injury. Am. J. Physiol. Physiol. 2009, 297, C1501–C1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagawa, S.; Matsuo, A.; Yagi, Y.; Ikematsu, K.; Tsuda, R.; Nakasono, I. The time-course analysis of gene expression during wound healing in mouse skin. Leg. Med. 2009, 11, 70–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takamiya, M.; Biwasaka, H.; Saigusa, K.; Nakayashiki, N.; Aoki, Y. Wound age estimation by simultaneous detection of 9 cytokines in human dermal wounds with a multiplex bead-based immunoassay: An estimative method using outsourced examinations. Leg. Med. 2009, 11, 186–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, T.-L.; Yuan, X.-T.; Yang, D.; Dai, H.-L.; Wang, W.-J.; Peng, X.; Shao, H.-J.; Jin, Z.-F.; Fu, Z.-J. Expression of HMGB1 and RAGE in rat and human brains after traumatic brain injury. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012, 72, 643–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, Y.-Y.; Zhang, S.-T.; Yu, L.-S.; Ye, G.-H.; Lin, K.-Z.; Wu, S.-Z.; Dong, M.-W.; Han, J.-G.; Feng, X.-P.; Li, X.-B. The time-dependent expression of α7nAChR during skeletal muscle wound healing in rats. Int. J. Leg. Med. 2014, 128, 779–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S.; Sun, R.; Zhou, Z.; Zhou, J.; Liang, J.; Mu, H. Expression of Amyloid-β Protein and Amyloid-β Precursor Protein After Primary Brain-Stem Injury in Rats. Am. J. Forensic Med. Pathol. 2014, 35, 201–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimura, A.; Ishida, Y.; Nosaka, M.; Shiraki, M.; Hama, M.; Kawaguchi, T.; Kuninaka, Y.; Shimada, E.; Yamamoto, H.; Takayasu, T.; et al. Autophagy in skin wounds: A novel marker for vital reactions. Int. J. Leg. Med. 2015, 129, 537–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birincioğlu, I.; Akbaba, M.; Alver, A.; Kul, S.; Özer, E.; Turan, N.; Şentürk, A.; Ince, I. Determination of skin wound age by using cytokines as potential markers. J. Forensic Leg. Med. 2016, 44, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Z.-L.; Jiang, S.-K.; Zhang, M.; Wang, M.; Li, J.-Y.; Zhao, R.; Wang, L.-L.; Li, S.-S.; Liu, M.; Zhang, M.-Z.; et al. Detection of satellite cells during skeletal muscle wound healing in rats: Time-dependent expressions of Pax7 and MyoD in relation to wound age. Int. J. Leg. Med. 2015, 130, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.-L.; Zhao, R.; Liu, C.-S.; Liu, M.; Li, S.-S.; Li, J.-Y.; Jiang, S.-K.; Zhang, M.; Tian, Z.-L.; Wang, M.; et al. A fundamental study on the dynamics of multiple biomarkers in mouse excisional wounds for wound age estimation. J. Forensic Leg. Med. 2016, 39, 138–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legaz Pérez, I.; Falcón, M.; Gimenez, M.; Diaz, F.M.; Pérez-Cárceles, M.D.; Osuna, E.; Nuno-Vieira, D.; Luna, A. Diagnosis of vitality in skin wounds in the ligature marks resulting from suicide hanging. Am. J. Forensic Med. Pathol. 2017, 38, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.-T.; Huang, H.-Y.; Qu, D.; Xue, Y.; Zhang, K.-K.; Xie, X.-L.; Wang, Q. CXCL1 and CXCR2 as potential markers for vital reactions in skin contusions. Forensic Sci. Med. Pathol. 2018, 14, 174–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, D.; Tan, X.-H.; Zhang, K.-K.; Wang, Q.; Wang, H.-J. ATF3 mRNA, but not BTG2, as a possible marker for vital reaction of skin contusion. Forensic Sci. Int. 2019, 303, 109937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peyron, P.-A.; Colomb, S.; Becas, D.; Adriansen, A.; Gauchotte, G.; Tiers, L.; Marin, G.; Lehmann, S.; Baccino, E.; Delaby, C.; et al. Cytokines as new biomarkers of skin wound vitality. Int. J. Leg. Med. 2021, 135, 2537–2545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Betz, P.; Nerlich, A.; Wilskel, J.; Tübel, J.; Wiest, I.; Penning, R.; Eisenmenger, W. Immunohistochemical localization of fibronectin as a tool for the age determination of human skin wounds. Int. J. Leg. Med. 1992, 105, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Betz, P.; Nerlich, A.; Wilske, J.; Tübel, J.; Penning, R.; Eisenmengen, W. The immunohistochemical localization of alpha1-antichymotrypsin and fibronectin and its meaning for the determination of the vitality of human skin wounds. Int. J. Leg. Med. 1993, 105, 223–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fieguth, A.; Kleemann, W.J. Immunohistochemical examination of skin wounds with antibodies against alpha-1-antichymotrypsin, alpha-2-macroglobulin and lysozyme. Int. J. Leg. Med. 1994, 107, 29–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betz, P.; Eisenmenger, W. Immunohistochemical analysis of markers for different macrophage phenotypes and their use for a forensic wound age estimation. Int. J. Leg. Med. 1995, 107, 197–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondo, T.; Ohshima, T. The dynamics of inflammatory cytokines in the healing process of mouse skin wound: A preliminary study for possible wound age determination. Int. J. Leg. Med. 1996, 108, 231–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreßler, J.; Bachmann, L.; Müller, E. Enhanced expression of ICAM-1 (CD 54) in human skin wounds: Diagnostic value in legal medicine. Agents Actions 1997, 46, 434–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dressler, J.; Bachmann, L.; Kasper, M.; Hauck, J.G.; Müller, E. Time dependence of the expression of ICAM-1 (CD 54) in human skin wounds. Int. J. Leg. Med. 1997, 110, 299–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fieguth, A.; Kleemann, W.J.; von Wasielewski, R.; Werner, M.; Tröger, H.D. Influence of postmortem changes on immunohistochemical reactions in skin. Int. J. Leg. Med. 1997, 110, 18–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreßler, J.; Bachmann, L.; Koch, R.; Müller, E. Enhanced expression of selectins in human skin wounds. Int. J. Leg. Med. 1998, 112, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grellner, W.; Dimmeler, S.; Madea, B. Immunohistochemical detection of fibronectin in postmortem incised wounds of porcine skin. Forensic Sci. Int. 1998, 97, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabata, N. Morphological changes in traumatized skeletal muscle: The appearance of ‘opaque fibers’ of cervical muscles as evidence of compression of the neck. Forensic Sci. Int. 1998, 96, 197–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreßler, J.; Bachmann, L.; Koch, R.; Müller, E. Estimation of wound age and VCAM-1 in human skin. Int. J. Leg. Med. 1999, 112, 159–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dressler, J.; Bachmann, L.; Strejc, P.; Koch, R.; Müller, E. Expression of adhesion molecules in skin wounds: Diagnostic value in legal medicine. Forensic Sci. Int. 2000, 113, 173–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondo, T.; Ohshima, T.; Eisenmenger, W. Immunohistochemical and morphometrical study on the temporal expression of interleukin-1α (IL-1α) in human skin wounds for forensic wound age determination. Int. J. Leg. Med. 1999, 112, 249–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kondo, T.; Ohshima, T.; Sato, Y.; Mayama, T.; Eisenmenger, W. Immunohistochemical study on the expression of c-Fos and c-Jun in human skin wounds. Histochem. J. 2000, 32, 509–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Psaroudakis, K.; Tzatzarakis, M.N.; Tsatsakis, A.M.; Michalodimitrakis, M.N. The application of histochemical methods to the age evaluation of skin wounds: Experimental study in rabbits. Am. J. Forensic Med. Pathol. 2001, 22, 341–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hausmann, R.; Betz, P. The course of MIB-1 expression by cerebral macrophages following human brain injury. Leg. Med. 2002, 4, 79–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondo, T.; Ohshima, T.; Mori, R.; Guan, D.W.; Ohshima, K.; Eisenmenger, W. Immunohistochemical detection of chemokines in human skin wounds and its application to wound age determination. Int. J. Leg. Med. 2002, 116, 87–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondo, T.; Tanaka, J.; Ishida, Y.; Mori, R.; Takayasu, T.; Ohshima, T. Ubiquitin expression in skin wounds and its application to forensic wound age determination. Int. J. Leg. Med. 2002, 116, 267–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortiz-Rey, J.; Suárez-Peñaranda, J.; Da Silva, E.; Muñoz-Barús, J.I.; Miguel-Fraile, P.S.; De la Fuente-Buceta, A.; Concheiro-Carro, L. Immunohistochemical detection of fibronectin and tenascin in incised human skin injuries. Forensic Sci. Int. 2002, 126, 118–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez-Peñaranda, J.M.; Rodríguez-Calvo, M.S.; Ortiz-Rey, J.A.; Muñoz, J.I.; Sánchez-Pintos, P.; Da Silva, E.A.; De la Fuente-Buceta, A.; Concheiro-Carro, L. Demonstration of apoptosis in human skin injuries as an indicator of vital reaction. Int. J. Leg. Med. 2002, 116, 109–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonelli, A.; Bacci, S.; Norelli, G.A. Affinity cytochemistry analysis of mast cells in skin lesions: A possible tool to assess the timing of lesions after death. Int. J. Leg. Med. 2003, 117, 331–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fieguth, A.; Franz, D.; Lessig, R.; Kleemann, W.J. Fatal trauma to the neck: Immunohistochemical study of local injuries. Forensic Sci. Int. 2003, 135, 218–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fieguth, A.; Feldbrügge, H.; Gerich, T.; Kleemann, W.; Tröger, H. The time-dependent expression of fibronectin, MRP8, MRP14 and defensin in surgically treated human skin wounds. Forensic Sci. Int. 2003, 131, 156–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauchotte, G.; Wissler, M.-P.; Casse, J.-M.; Pujo, J.; Minetti, C.; Gisquet, H.; Vigouroux, C.; Plénat, F.; Vignaud, J.-M.; Martrille, L. FVIIIra, CD15, and tryptase performance in the diagnosis of skin stab wound vitality in forensic pathology. Int. J. Leg. Med. 2013, 127, 957–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-Rey, J.A.; Suárez-Peñaranda, J.M.; Muñoz-Barús, J.I.; Álvarez, C.; Miguel, P.S.; Rodríguez-Calvo, M.S.; Concheiro-Carro, L. Expression of fibronectin and tenascin as a demonstration of vital reaction in rat skin and muscle. Int. J. Leg. Med. 2003, 117, 356–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, T.; Ishida, Y.; Kimura, A.; Takayasu, T.; Eisenmenger, W.; Kondo, T. Forensic application of VEGF expression to skin wound age determination. Int. J. Leg. Med. 2004, 118, 320–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balažic, J.; Grajn, A.; Kralj, E.; Šerko, A.; Štefanič, B. Expression of fibronectin suicidal in gunshot wounds. Forensic Sci. Int. 2005, 147, S5–S7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacci, S.; Romagnoli, P.; Norelli, G.A.; Forestieri, A.L.; Bonelli, A. Early increase in TNF-alpha-containing mast cells in skin lesions. Int. J. Leg. Med. 2005, 120, 138–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarran, S.; Langlois, N.E.I.; Dziewulski, P.; Sztynda, T. Using the Inflammatory Cell Infiltrate to Estimate the Age of Human Burn Wounds: A review and immunohistochemical study. Med. Sci. Law 2006, 46, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takamiya, M.; Fujita, S.; Saigusa, K.; Aoki, Y. Simultaneous detection of eight cytokines in human dermal wounds with a multiplex bead-based immunoassay for wound age estimation. Int. J. Leg. Med. 2007, 122, 143–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takamiya, M.; Fujita, S.; Saigusa, K.; Aoki, Y. Simultaneous Detections of 27 Cytokines during Cerebral Wound Healing by Multiplexed Bead-Based Immunoassay for Wound Age Estimation. J. Neurotrauma 2007, 24, 1833–1844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishida, Y.; Kimura, A.; Takayasu, T.; Eisenmenger, W.; Kondo, T. Expression of oxygen-regulated protein 150 (ORP150) in skin wound healing and its application for wound age determination. Int. J. Leg. Med. 2008, 122, 409–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-Rey, J.A.; Suárez-Peñaranda, J.M.; San Miguel, P.; Muñoz, J.I.; Rodríguez-Calvo, M.S.; Concheiro, L. Immunohistochemical analysis of P-Selectin as a possible marker of vitality in human cutaneous wounds. J. Forensic Leg. Med. 2008, 15, 368–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neri, M.; D’Errico, S.; Fiore, C.; Pomara, C.; Rabozzi, R.; Riezzo, I.; Turillazzi, E.; Greco, P.; Fineschi, V. Stillborn or liveborn? Comparing umbilical cord immunohistochemical expression of vitality markers (tryptase, α1-antichymotrypsin and CD68) by quantitative analysis and confocal laser scanning microscopy. Pathol.-Res. Pract. 2009, 205, 534–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogami, M.; Hoshi, T.; Arai, T.; Toukairin, Y.; Takama, M.; Takahashi, I. Morphology of lymphatic regeneration in rat incision wound healing in comparison with vascular regeneration. Leg. Med. 2009, 11, 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oehmichen, M.; Jakob, S.; Mann, S.; Saternus, K.S.; Pedal, I.; Meissner, C. Macrophage subsets in mechanical brain injury (MBI)—A contribution to timing of MBI based on immunohistochemical methods: A pilot study. Leg. Med. 2009, 11, 118–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohnert, M.; Anderson, J.; Rothschild, M.A.; Böhm, J. Immunohistochemical expression of fibronectin in the lungs of fire victims proves intravital reaction in fatal burns. Int. J. Leg. Med. 2010, 124, 583–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattaneo, C.; Andreola, S.; Marinelli, E.; Poppa, P.; Porta, D.; Grandi, M. The detection of microscopic markers of hemorrhaging and wound age on dry bone: A pilot study. Am. J. Forensic Med. Pathol. 2010, 31, 22–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, J.-Y.; Lee, S.-H.; Yoon, H.-J. A comparative study of wound healing following incision with a scalpel, diode laser or Er,Cr:YSGG laser in guinea pig oral mucosa: A histological and immunohistochemical analysis. Acta Odontol. Scand. 2010, 68, 232–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guler, H.; Aktas, E.O.; Karali, H.; Aktas, S. The Importance of Tenascin and Ubiquitin in Estimation of Wound Age. Am. J. Forensic Med. Pathol. 2011, 32, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryu, S.-W.; Lee, S.-H.; Yoon, H.-J. A comparative histological and immunohistochemical study of wound healing following incision with a scalpel, CO2laser or Er,Cr:YSGG laser in the Guinea pig oral mucosa. Acta Odontol. Scand. 2011, 70, 448–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taborelli, A.; Andreola, S.; Di Giancamillo, A.; Gentile, G.; Domeneghini, C.; Grandi, M.; Cattaneo, C. The use of the anti-Glycophorin a antibody in the detection of red blood cell residues in human soft tissue lesions decomposed in air and water: A pilot study. Med. Sci. Law 2011, 51, 16–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capatina, C.O.; Ceausu, M.; Curca, G.C.; Tabirca, D.D.; Hostiuc, S. Immunophenotypical expression of adhesion molecules in vital reaction. Rom. J. Leg. Med. 2012, 20, 185–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cecchi, R.; Aromatario, M.; Frati, P.; Lucidi, D.; Ciallella, C. Death due to crush injuries in a compactor truck: Vitality assessment by immunohistochemistry. Int. J. Leg. Med. 2012, 126, 957–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishida, Y.; Kimura, A.; Nosaka, M.; Kuninaka, Y.; Takayasu, T.; Eisenmenger, W.; Kondo, T. Immunohistochemical analysis on cyclooxygenase-2 for wound age determination. Int. J. Leg. Med. 2012, 126, 435–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.-L.; Yu, T.-S.; Li, X.-N.; Fan, Y.-Y.; Ma, W.-X.; Du, Y.; Zhao, R.; Guan, D.-W. Cannabinoid receptor type 2 is time-dependently expressed during skin wound healing in mice. Int. J. Leg. Med. 2012, 126, 807–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capatina, C.; Ceausu, M.; Hostiuc, S. Usefulness of Fibronectin and P-selectin as markers for vital reaction in uncontrolled conditions. Rom. J. Leg. Med. 2013, 21, 281–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Agha, A. Histological study and immunohistochemical expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase and vascular endothelial growth factor in skin wound healing and its application for forensic wound age determination. Al-Azhar J. Pharm. Sci. 2013, 48, 58–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbaba, M.; Kara, S.; Demir, T.; Temizer, M.; Dulger, H.; Bakir, K. Immunohistochemical determination of wound age in mice. Gaziantep Med. J. 2014, 20, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacci, S.; Defraia, B.; Cinci, L.; Calosi, L.; Guasti, D.; Pieri, L.; Lotti, V.; Bonelli, A.; Romagnoli, P. Immunohistochemical analysis of dendritic cells in skin lesions: Correlations with survival time. Forensic Sci. Int. 2014, 244, 179–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cecchi, R.; Sestili, C.; Prosperini, G.; Cecchetto, G.; Vicini, E.; Viel, G.; Muciaccia, B. Markers of mechanical asphyxia: Immunohistochemical study on autoptic lung tissues. Int. J. Leg. Med. 2013, 128, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kubo, H.; Hayashi, T.; Ago, K.; Ago, M.; Kanekura, T.; Ogata, M. Forensic diagnosis of ante- and postmortem burn based on aquaporin-3 gene expression in the skin. Leg. Med. 2014, 16, 128–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montisci, M.; Corradin, M.; Giacomelli, L.; Viel, G.; Cecchetto, G.; Ferrara, S.D. Can immunohistochemistry quantification of Cathepsin-D be useful in the differential diagnosis between vital and post-mortem wounds in humans? Med. Sci. Law 2014, 54, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van de Goot, F.R.; Korkmaz, H.I.; Fronczek, J.; Witte, B.I.; Visser, R.; Ulrich, M.M.; Begieneman, M.P.; Rozendaal, L.; Krijnen, P.A.; Niessen, H.W. A new method to determine wound age in early vital skin injuries: A probability scoring system using expression levels of Fibronectin, CD62p and Factor VIII in wound hemorrhage. Forensic Sci. Int. 2014, 244, 128–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capatina, C.O.; Chirica, V.I.; Martius, E.; Isaila, O.M.; Ceausu, M. Are P-selectin and fibronectin truly useful for the vital reaction? Case presentation. Rom. J. Leg. Med. 2015, 23, 91–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Deeb, N.M.F.; Badr El Dine, F.M. Evaluation of lymphatic regeneration in rat incisional wound healing and its use in wound age estimation. Alex. J. Med. 2015, 51, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Fronczek, J.; Lulf, R.; Korkmaz, H.I.; Witte, B.I.; van de Goot, F.R.; Begieneman, M.P.; Schalkwijk, C.; Krijnen, P.A.; Rozendaal, L.; Niessen, H.W.; et al. Analysis of inflammatory cells and mediators in skin wound biopsies to determine wound age in living subjects in forensic medicine. Forensic Sci. Int. 2015, 247, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishida, Y.; Kimura, A.; Nosaka, M.; Kuninaka, Y.; Shimada, E.; Yamamoto, H.; Nishiyama, K.; Inaka, S.; Takayasu, T.; Eisenmenger, W.; et al. Detection of endothelial progenitor cells in human skin wounds and its application for wound age determination. Int. J. Leg. Med. 2015, 129, 1049–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kara1, S.; Akbaba, M.; Kul, S.; Bakır, K. Is it possible to make early wound age estimation by immunohistochemical methods? Rom. J. Leg. Med. 2016, 24, 92–99. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, T.S.; Li, Z.; Zhao, R.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Z.-H.; Guan, D.W. Time-dependent Expression of MMP-2 and TIMP-2 after Rats Skeletal Muscle Contusion and Their Application to Determine Wound Age. J. Forensic Sci. 2016, 61, 527–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abo El-Noor, M.M.; Elgazzar, F.M.; Alshenawy, H.A. Role of inducible nitric oxide synthase and interleukin-6 expression in estimation of skin burn age and vitality. J. Forensic Leg. Med. 2017, 52, 148–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, X.-Y.; Chen, Y.; Ye, G.-H.; Dong, M.-W.; Lin, K.-Z.; Han, J.-G.; Feng, X.-P.; Li, X.-B.; Yu, L.-S.; Fan, Y.-Y. Detection of RAGE expression and its application to diabetic wound age estimation. Int. J. Leg. Med. 2017, 131, 691–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legaz, I.; Pérez-Cárceles, M.D.; Gimenez, M.; Martínez-Díaz, F.; Osuna, E.; Luna, A. Immunohistochemistry as a tool to characterize human skin wounds of hanging marks. Rom. J. Leg. Med. 2018, 26, 354–358. [Google Scholar]

- Murase, T.; Yamamoto, T.; Koide, A.; Yagi, Y.; Kagawa, S.; Tsuruya, S.; Abe, Y.; Umehara, T.; Ikematsu, K. Temporal expression of chitinase-like 3 in wounded murine skin. Rom. J. Leg. Med. 2017, 131, 1623–1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doberentz, E.; Madea, B. Supravital expression of heat-shock proteins. Forensic Sci. Int. 2018, 294, 10–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishida, Y.; Kuninaka, Y.; Furukawa, F.; Kimura, A.; Nosaka, M.; Fukami, M.; Yamamoto, H.A.; Kato, T.; Shimada, E.; Hata, S.; et al. Immunohistochemical analysis on aquaporin-1 and aquaporin-3 in skin wounds from the aspects of wound age determination. Forensic Sci. Int. 2017, 132, 237–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metwally, E.S.; Madboly, A.G.; Farag, A.; Abdelaziz, T.A.; Farag, H.A. Reliability of Fibronectin and P-selectin as Indicators of Vitality and Age of Wounds: An Immunohistochemical Study on Human Skin Wounds. Mansoura J. Forensic Med. Clin. Toxicol. 2018, 26, 83–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Matteis, A.; dell’Aquila, M.; Maiese, A.; Frati, P.; La Russa, R.; Bolino, G.; Fineschi, V. The Troponin-I fast skeletal muscle is reliable marker for the determination of vitality in the suicide hanging. Forensic Sci. Int. 2019, 301, 284–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Focardi, M.; Puliti, E.; Grifoni, R.; Palandri, M.; Bugelli, V.; Pinchi, V.; Norelli, G.A.; Bacci, S. Immunohistochemical localization of Langerhans cells as a tool for vitality in hanging mark wounds: A pilot study. Aust. J. Forensic Sci. 2019, 52, 393–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalaf, A.A.; Hassanen, E.I.; Zaki, A.R.; Tohamy, A.F.; Ibrahim, M.A. Histopathological, immunohistochemical, and molecular studies for determination of wound age and vitality in rats. Int. Wound J. 2019, 16, 1416–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Focardi, M.; Bugelli, V.; Venturini, M.; Bianchi, I.; Defraia, B.; Pinchi, V.; Bacci, S. Increased expression of iNOS by Langerhans cells in hanging marks. Aust. J. Forensic Sci. 2020, 54, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maiese, A.; De Matteis, A.; Bolino, G.; Turillazzi, E.; Frati, P.; Fineschi, V. Hypo-Expression of Flice-Inhibitory Protein and Activation of the Caspase-8 Apoptotic Pathways in the Death-Inducing Signaling Complex Due to Ischemia Induced by the Compression of the Asphyxiogenic Tool on the Skin in Hanging Cases. Diagnostics 2020, 10, 938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldari, B.; Vittorio, S.; Sessa, F.; Cipolloni, L.; Bertozzi, G.; Neri, M.; Cantatore, S.; Fineschi, V.; Aromatario, M. Forensic Application of Monoclonal Anti-Human Glycophorin A Antibody in Samples from Decomposed Bodies to Establish Vitality of the Injuries. A Preliminary Experimental Study. Healthcare 2021, 9, 514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertozzi, G.; Ferrara, M.; La Russa, R.; Pollice, G.; Gurgoglione, G.; Frisoni, P.; Alfieri, L.; De Simone, S.; Neri, M.; Cipolloni, L. Wound Vitality in Decomposed Bodies: New Frontiers Through Immunohistochemistry. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 802841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niedecker, A.; Huhn, R.; Ritz-Timme, S.; Mayer, F. Complex challenges of estimating the age and vitality of muscle wounds: A study with matrix metalloproteinases and their inhibitors on animal and human tissue samples. Int. J. Leg. Med. 2021, 135, 1843–1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prangenberg, J.; Doberentz, E.; Witte, A.-L.; Madea, B. Aquaporin 1 and 3 as local vitality markers in mechanical and thermal skin injuries. Int. J. Leg. Med. 2021, 135, 1837–1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegner, A.; Doberentz, E.; Madea, B. Death in the sauna-vitality markers for heat exposure. Int. J. Leg. Med. 2021, 135, 903–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khismatullin, R.R.; Shakirova, A.Z.; Weisel, J.W.; Litvinov, R.I. Age-dependent Differential Staining of Fibrin in Blood Clots and Thrombi. BioNanoScience 2020, 10, 370–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamboni, P.; De Mattei, M.; Ongaro, A.; Fogato, L.; Carandina, S.; De Palma, M.; Tognazzo, S.; Scapoli, G.L.; Serino, M.L.; Caruso, A.; et al. Factor XIII Contrasts the Effects of Metalloproteinases in Human Dermal Fibroblast Cultured Cells. Vasc. Endovascular Surg. 2004, 38, 431–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohshima, T.; Sato, Y. Time-dependent expression of interleukin-10 (IL-10) mRNA during the early phase of skin wound healing as a possible indicator of wound vitality. Int. J. Leg. Med. 1998, 111, 251–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, Y.; Ohshima, T. The expression of mRNA of proinflammatory cytokines during skin wound healing in mice: A preliminary study for forensic wound age estimation (II). Int. J. Leg. Med. 2000, 113, 140–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iino, M.; Nakatome, M.; Ogura, Y.; Fujimura, H.; Kuroki, H.; Inoue, H.; Ino, Y.; Fujii, T.; Terao, T.; Matoba, R. Real-time PCR quantitation of FE65 a beta-amyloid precursor protein-binding protein after traumatic brain injury in rats. Int. J. Leg. Med. 2003, 117, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takamiya, M.; Saigusa, K.; Nakayashiki, N.; Aoki, Y. Studies on mRNA expression of basic fibroblast growth factor in wound healing for wound age determination. Int. J. Leg. Med. 2003, 117, 46–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, R.; Wan, L.; Shi, M. The time-dependent expressions of IL-1beta, COX-2, MCP-1 mRNA in skin wounds of rabbits. Forensic Sci. Int. 2008, 175, 193–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.-H.; Wang, Y.-Y.; Zhang, L.; Gao, C.-R.; Zhang, L.-Z.; Guo, Z. Time-dependent expression of skeletal muscle troponin I mRNA in the contused skeletal muscle of rats: A possible marker for wound age estimation. Int. J. Leg. Med. 2009, 124, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.-H.; Nan, L.-H.; Gao, C.-R.; Wang, Y.-Y. Validation of reference genes for estimating wound age in contused rat skeletal muscle by quantitative real-time PCR. Int. J. Leg. Med. 2011, 126, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Q.-X.; Sun, J.-H.; Zhang, L.-Y.; Liang, X.-H.; Guo, X.-J.; Gao, C.-R.; Wang, Y.-Y. Time-dependent expression of SNAT2 mRNA in the contused skeletal muscle of rats: A possible marker for wound age estimation. Forensic Sci. Med. Pathol. 2013, 9, 528–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palagummi, S.; Harbison, S.; Fleming, R. A time-course analysis of mRNA expression during injury healing in human dermal injuries. Int. J. Leg. Med. 2013, 128, 403–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kameyama, H.; Udagawa, O.; Hoshi, T.; Toukairin, Y.; Arai, T.; Nogami, M. The mRNA expressions and immunohistochemistry of factors involved in angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis in the early stage of rat skin incision wounds. Leg. Med. 2015, 17, 255–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, X.-Y.; Du, Q.-X.; Li, S.-Q.; Sun, J.-H. Comparison of the homogeneity of mRNAs encoding SFRP5, FZD4, and Fosl1 in post-injury intervals: Subcellular localization of markers may influence wound age estimation. J. Forensic Leg. Med. 2016, 43, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, M.-Y.; Xu, D.; Liu, J.-C.; Lyu, H.-P.; Xue, Y.; He, J.-T.; Huang, H.-Y.; Zhang, K.-K.; Xie, X.-L.; Wang, Q. IL-6 and IL-20 as potential markers for vitality of skin contusion. J. Forensic Leg. Med. 2018, 59, 8–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Q.-X.; Li, N.; Dang, L.-H.; Dong, T.-N.; Lu, H.-L.; Shi, F.-X.; Jin, Q.-Q.; Jie, C.; Sun, J.-H. Temporal expression of wound healing–related genes inform wound age estimation in rats after a skeletal muscle contusion: A multivariate statistical model analysis. Int. J. Leg. Med. 2019, 134, 273–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Peng, H.; Ruan, Q.; Fatima, A.; Getsios, S.; Lavker, R.M. MicroRNA-205 promotes keratinocyte migration via the lipid phosphatase SHIP2. FASEB J. 2010, 24, 3950–3959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertero, T.; Gastaldi, C.; Bourget-Ponzio, I.; Imbert, V.; Loubat, A.; Selva, E.; Busca, R.; Mari, B.; Hofman, P.; Barbry, P.; et al. miR-483-3p controls proliferation in wounded epithelial cells. FASEB J. 2011, 25, 3092–3105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Wang, J.; Guo, S.-L.; Fan, K.-J.; Li, J.; Wang, Y.-L.; Teng, Y.; Yang, X. miR-21 Promotes Keratinocyte Migration and Re-epithelialization during Wound Healing. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2013, 9, 480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Pastar, I.; Khan, A.A.; Stojadinovic, O.; Lebrun, E.A.; Medina, M.C.; Brem, H.; Kirsner, R.S.; Jimenez, J.J.; Leslie, C.; Tomic-Canic, M. Induction of Specific MicroRNAs Inhibits Cutaneous Wound Healing. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 29324–29335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viticchiè, G.; Lena, A.M.; Cianfarani, F.; Odorisio, T.; Annicchiarico-Petruzzelli, M.; Melino, G.; Candi, E. MicroRNA-203 contributes to skin re-epithelialization. Cell Death Dis. 2012, 3, e435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Feng, Y.; Sun, H.; Zhang, L.; Hao, L.; Shi, C.; Wang, J.; Li, R.; Ran, X.; Su, Y.; et al. miR-21 Regulates Skin Wound Healing by Targeting Multiple Aspects of the Healing Process. Am. J. Pathol. 2012, 181, 1911–1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, Y.; Tymen, S.D.; Chen, D.; Fang, Z.J.; Zhao, Y.; Dragas, D.; Dai, Y.; Marucha, P.T.; Zhou, X. MicroRNA-99 Family Targets AKT/mTOR Signaling Pathway in Dermal Wound Healing. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e64434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, D.; Halilovic, A.; Yue, P.; Bellner, L.; Wang, K.; Wang, L.; Zhang, C. Inhibition of miR-205 Impairs the Wound-Healing Process in Human Corneal Epithelial Cells by Targeting KIR4.1 (KCNJ10). Investig. Opthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2013, 54, 6167–6178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, P.; He, Q.; Luo, C.; Qian, L. Differentially expressed miRNAs in acute wound healing of the skin: A pilot study. Medicine 2015, 94, e458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Icli, B.; Nabzdyk, C.S.; Lujan-Hernandez, J.; Cahill, M.; Auster, M.E.; Wara, A.; Sun, X.; Ozdemir, D.; Giatsidis, G.; Orgill, D.P.; et al. Regulation of impaired angiogenesis in diabetic dermal wound healing by microRNA-26a. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2016, 91, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etich, J.; Bergmeier, V.; Pitzler, L.; Brachvogel, B. Identification of a reference gene for the quantification of mRNA and miRNA expression during skin wound healing. Connect. Tissue Res. 2016, 58, 196–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, H.; Zhao, F.; Zhang, T.; Liu, X.; Wang, Z.; Wang, R.; Shi, P.; Pang, X. MicroRNA-149 contributes to scarless wound healing by attenuating inflammatory response. Mol. Med. Rep. 2017, 16, 2156–2162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, S.; Zhao, N.; Ge, L.; Wang, G.; Ran, X.; Wang, J.; Su, Y.; Wang, T. MiR-21 ameliorates age-associated skin wound healing defects in mice. J. Gene Med. 2018, 20, e3022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, H.-P.; Cheng, M.; Liu, J.-C.; Ye, M.-Y.; Xu, D.; He, J.-T.; Xie, X.-L.; Wang, Q. Differentially expressed microRNAs potential markers for vital reaction of burned skin. J. Forensic Med. 2018, 4, 135–141. [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim, S.F.; Ali, M.M.; Basyouni, H.; Rashed, L.A.; Amer, E.A.E.; El-Kareem, D.A. Histological and miRNAs postmortem changes in incisional wound. Egypt. J. Forensic Sci. 2019, 9, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neri, M.; Fabbri, M.; D’Errico, S.; Di Paolo, M.; Frati, P.; Gaudio, R.M.; La Russa, R.; Maiese, A.; Marti, M.; Pinchi, E.; et al. Regulation of miRNAs as new tool for cutaneous vitality lesions demonstration in ligature marks in deaths by hanging. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 20011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, L.; Sun, Y.; Xu, M.; Zeng, F.; Xiong, X. miR-203 Acts as an Inhibitor for Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition Process in Diabetic Foot Ulcers via Targeting Interleukin-8. Neuroimmunomodulation 2019, 26, 239–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, G.; Chen, B.; Zhang, X.; Chen, H. Human Adipose-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells-Derived Exosomal microRNA-19b Promotes the Healing of Skin Wounds Through Modulation of the CCL1/TGF-β Signaling Axis. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol. Biosci. Rep. 2020, 13, 957–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, L.; Zhu, C.; Jia, J.; Hao, X.-Y.; Yu, X.-Y.; Liu, X.-Y.; Shu, M.-G. ADSC-Exos containing MALAT1 promotes wound healing by targeting miR-124 through activating Wnt/β-catenin pathway. Biosci. Rep. 2020, 40, BSR20192549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Wei, J.; Yang, W.; Li, W.; Liu, F.; Yan, X.; Yan, X.; Hu, N.; Li, J. MicroRNA-26a inhibits wound healing through decreased keratinocytes migration by regulating ITGA5 through PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. Biosci. Rep. 2020, 40, BSR20201361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Shu, B.; Zhou, Z.; Xu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, P.; Xiong, K.; Xie, J. Involvement of miRNA203 in the proliferation of epidermal stem cells during the process of DM chronic wound healing through Wnt signal pathways. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2020, 11, 348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Cheng, M.; Xu, J.; Chen, L.; Li, J.; Li, Q.; Xie, X.; Wang, Q. MiR-711 and miR-183-3p as potential markers for vital reaction of burned skin. Forensic Sci. Res. 2020, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Peng, H.; Qu, L.; Sommar, P.; Wang, A.; Chu, T.; Li, X.; Bi, X.; Liu, Q.; Sérézal, I.G.; et al. miR-19a/b and miR-20a Promote Wound Healing by Regulating the Inflammatory Response of Keratinocytes. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2020, 141, 659–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacNeil, T.; Vathiotis, I.A.; Martinez-Morilla, S.; Yaghoobi, V.; Zugazagoitia, J.; Liu, Y.; Rimm, D.L. Antibody validation for protein expression on tissue slides: A protocol for immunohistochemistry. BioTechniques 2020, 69, 460–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambella, A.; Porro, L.; Pigozzi, S.; Fiocca, R.; Grillo, F.; Mastracci, L. Section detachment in immunohistochemistry: Causes, troubleshooting, and problem-solving. Histochem. Cell Biol. 2017, 3, 4–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhury, K.R.; Yagle, K.J.; Swanson, P.E.; Krohn, K.A.; Rajendran, J.G. A Robust Automated Measure of Average Antibody Staining in Immunohistochemistry Images. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 2009, 58, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzardi, A.E.; Johnson, A.T.; Vogel, R.I.; Pambuccian, S.E.; Henriksen, J.; Skubitz, A.P.; Metzger, G.J.; Schmechel, S.C. Quantitative comparison of immunohistochemical staining measured by digital image analysis versus pathologist visual scoring. Diagn. Pathol. 2012, 7, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konsti, J.; Lundin, M.; Linder, N.; Haglund, C.; Blomqvist, C.; Nevanlinna, H.; Aaltonen, K.; Nordling, S.; Lundin, J. Effect of image compression and scaling on automated scoring of immunohistochemical stainings and segmentation of tumor epithelium. Diagn. Pathol. 2012, 7, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asimaki, A.; Tandri, H.; Huang, H.; Halushka, M.K.; Gautam, S.; Basso, C.; Thiene, G.; Tsatsopoulou, A.; Protonotarios, N.; McKenna, W.J.; et al. A New Diagnostic Test for Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Cardiomyopathy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009, 360, 1075–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kemp, W.L. Postmortem Change and its Effect on Evaluation of Fractures. Acad. Forensic Pathol. 2016, 6, 28–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wheatley, B.P. Perimortem or Postmortem Bone Fractures? An Experimental Study of Fracture Patterns in Deer Femora. J. Forensic Sci. 2008, 53, 69–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grellner, W.; Madea, B. Demands on scientific studies: Vitality of wounds and wound age estimation. Forensic Sci. Int. 2007, 165, 150–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dettmeyer, R.B.; Verhoff, M.A.; Schutz, H.F. Vital reactions. In Forensic Medicine; Dettmeyer, R.B., Verhoff, M.A., Schutz, H.F., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany; New York, NY, USA, 2014; p. 107. [Google Scholar]

- Taboubi, S.; Milanini, J.; Delamarre, E.; Parat, F.; Garrouste, F.; Pommier, G.; Takasaki, J.; Hubaud, J.; Kovacic, H.; Lehmann, M. Galpha(q/11)-coupled P2Y2 nucleotide receptor inhibits human keratinocyte spreading and migration. FASEB J. 2007, 21, 4047–4058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakinuma, N.; Roy, B.C.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Kiyama, R. Kank regulates RhoA-dependent formation of actin stress fibers and cell migration via 14-3-3 in PI3K-Akt signaling. J. Cell Biol. 2008, 181, 537–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Squarize, C.H.; Castilho, R.M.; Bugge, T.H.; Gutkind, J.S. Accelerated Wound Healing by mTOR Activation in Genetically Defined Mouse Models. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e10643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whyte, J.L.; Smith, A.A.; Helms, J.A. Wnt Signaling and Injury Repair. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2012, 4, a008078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Ishida, Y.; Ishigami, A.; Nosaka, M.; Kuninaka, Y.; Hata, S.; Yamamoto, H.; Hashizume, Y.; Matsuki, J.; Yasuda, H.; et al. Forensic Application of Epidermal Ubiquitin Expression to Determination of Wound Vitality in Human Compressed Neck Skin. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 867365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishida, Y.; Nosaka, M.; Kondo, T. Bone Marrow-Derived Cells and Wound Age Estimation. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 822572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ros, A.C.; Bacci, S.; Luna, A.; Legaz, I. Forensic Impact of the Omics Science Involved in the Wound: A Systematic Review. Front. Med. 2022, 8, 786798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gitto, L.; Bonaccorso, L.; Maiese, A.; dell’Aquila, M.; Arena, V.; Bolino, G. A scream from the past: A multidisciplinary approach in a concealment of a corpse found mummified. J. Forensic Leg. Med. 2015, 32, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prangenberg, J.; Doberentz, E.; Madea, B. Mini Review: Forensic Value of Aquaporines. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 793140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casse, J.M.; Martrille, L.; Vignaud, J.M.; Gauchotte, G. Skin Wounds Vitality Markers in Forensic Pathology: An Updated Review. Med. Sci. Law. 2016, 56, 128–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamboni, P.; Gemmati, D. Clinical Implications of Gene Polymorphisms in Venous Leg Ulcer: A Model in Tissue Injury and Reparative Process. Thromb. Haemost. 2007, 98, 131–137. [Google Scholar]

- Maiese, A.; Del Duca, F.; Santoro, P.; Pellegrini, L.; De Matteis, A.; La Russa, R.; Frati, P.; Fineschi, V. An Overview on Actual Knowledge About Immunohistochemical and Molecular Features of Vitality, Focusing on the Growing Evidence and Analysis to Distinguish Between Suicidal and Simulated Hanging. Front. Med. (Lausanne) 2022, 8, 793539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dell’aquila, M.; Maiese, A.; De Matteis, A.; Viola, R.V.; Arcangeli, M.; La Russa, R.; Fineschi, V. Traumatic brain injury: Estimate of the age of the injury based on neuroinflammation, endothelial activation markers and adhesion molecules. Histol. Histopathol. 2021, 36, 795–806. [Google Scholar]

| Biological Fluids | ||||

| References | Type of Paper | Model | Fluid | Brief Description |

| Zhu et al. 2001 [20] | Original research | Human | Urine | The study aimed to investigate differential PM urinary Mb levels for determining the cause of death. PMI < 48 h did not influence urinary Mb levels, while PMI > 48 h showed increased levels (PM/putrefactive changes). Urinary Mb levels were increased when survival time was longer (>12–24 h, no linear correlation), as well as in some cases of vital muscle damage (e.g., fire fatalities, drowning, and head trauma), while they were not in cases of natural death due to MI. In cases of minor muscle damage (e.g., head traumas), the urinary Mb elevation was related to the survival time. The comparison between traumatic and non-traumatic deaths was not performed. |

| Quan et al. 2008 [11] | Original research | Human | Serum | Autoptic samples were analyzed (PMI tested < 48 h). EPO levels were increased in blunts produced 7 days after death, and its increase was higher in non-acute deaths due to wounds. |

| Amany Abdel-Raham et al. 2018 [21] | Original research | Animal | CSF | K+ was significantly higher in TBI than in controls (no traumatized animal) when the samples were collected 12 h after death (no statistical difference when PMI < 12 h). Na+ was significantly higher in controls than TBI, when the samples were collected at the time of death and 6 h after death. Ca2+ was significantly higher in TBI than controls, when the samples were collected at the time of death and 6 h after death, while it was higher in controls than TBI, when the PMI was 12 h; albumin was higher in TBI than controls only at the time of death (no statistical difference when PMI was 6 or 12 h). The total leucocytic count was significantly higher in TBI than controls, regardless to the PMI (PMI tested 0–12 h). |

| Plasma | Uric acid and ammonia were significantly higher in TBI than in controls, regardless of the PMI (PMI tested 0–12 h). Lactic acid was significantly higher in TBI than controls only at the time of death and 12 h after death; hypoxanthine was significantly higher in TBI than controls at 6 and 12 h after death. | |||

| Serum | TNFα and IL-1β were significantly higher in TBI than in controls, regardless of the PMI (PMI tested 0–12 h). HMGB1 was significantly higher in TBI than in controls at 6 and 12 h after death. | |||

| Kobeissy et al. 2022 [22] | Original research | Animal | Serum | IL1- β, IL-6, and IL-10 were significantly higher in TBI than in controls. |

| Tissues | ||||

| References | Type of Paper | Model | Tissue | Brief Description |

| Njau et al. 1991 [23] | Original research | Animal | Skin | In wounded skin, Mg2+ decreased within 30 min, increased and peaked at the 2nd hour after wounding, then gradually decreased until the 8th hour. Ca2+ increased within 1 h after wounding, then decreased; however, at the 4th hour, it increased again until the 8th hour. Zn2+ increased within the first 120 min, then decreased gradually until the 8th hour. No statistical significance was found among different sites of sampling (the lesion, 2 cm from the lesion, and 4 cm from the lesion). Survival time tested in this study: 30 s; 30 min; 1, 2, 4, and 8 h after wounding. |

| Chen et al. 1995 [24] | Original research | Human | Skin, muscle | Fe2+ concentration in vital wounded skin (different types of lesions) was significantly higher than in controls (not injured skin of the same subjects). Survival time ranged from 5 min to 6 h. PMI ranged from 24 to 72 h. |

| He et al. 1996 [25] | Original research | Human | Skin | LTB4 was only detectable in vital skin lesions and not in wounds inflicted after death. It was also detectable in formalin-fixed injured skin if fixation < 10 days. PMI ranged from 4 h to 1 day. |

| Laiho et al. 1998 [26] | Original research | Animal | Skin | MPO was high in vital skin lesions, but no comparison with normal skin or PM injured skin controls was done. MPO activity depended on blood loss (decreased activity with 35% loss of blood), the depth of the lesion (deeper lesions, higher activity), and skin thickness (thicker skin, higher activity). |

| Grellner et al. 2000 [27] | Original research | Human | Skin | The study found great interindividual variability in cytokine levels. In autoptic samples, IL-1β levels were significantly higher in wounded skin than in controls (normal skin) only when the wound age was ≤5 min. IL-6 levels were significantly higher in wounded skin than in controls when the wound age was ≤5 min and >24 h. TNF-α levels were significantly higher in wounded skin than in controls only when the wound age was ≤5 min. |

| Laiho et al. 2004 [28] | Original research | Animal | Skin | Significantly increased albumin levels in vital skin lesions (incision, excoriation, heat, and freezing injuries) with different ages (from 5 min to 15 days for incision, 5 min to 4 weeks for excoriations, and 60 min to 2 weeks for heat and freezing injuries) and sampled soon after death. Still significantly increased in incision wounds aged 15 and 30 min and excoriation aged 30 and 60 min when sampled 3 days after death. |

| Barnes et al. 2009 [29] * | Original research | Animal | Skeletal muscle | MT1-MMP levels significantly decreased in muscular injuries aged 48- and 72-h post-injury, compared to controls. TIMP-2 protein was decreased muscular injuries aged 3- and 48-h post-injury, compared to controls. |

| Kagawa et al. 2009 [30] | Original research | Animal | Skin | In vital lesions, C-fos, fosB, and MKP-1 peaked 1 h after injury; CD14 and CCL9 peaked between 12 and 24 h after injury, while PlGF and MCP-5 before 5 days after injury. |

| Takamiya et al. 2009 [31] | Original research | Human | Skin | IL12+ in less than 30 min after injury, at 2 h IL5, IL13, and IL17+. By 9 h after wounding MCP1, IL1ß, G-CSF, and MIP1ß showed+, while IL5 and IL13 peaked. IL17+ increased until 33–49 h and IL 12+ until 71–116 h. IL7 negativity from early phases of wound healing. |

| Gao et al. 2012 [32] | Original research | Animal | Brain | HMGB1 decreased in the first 6 h after TBI, coming back to baseline in 2 days. RAGE increased 1 h after TBI and peaked 6 h after TBI. PMI tested 6–72 h. |

| Fan et al. 2014 [33] * | Original research | Animal | Skeletal muscle | In vital skeletal muscle injuries, α7nAChR and GAPDH levels significantly increased from 12 h to 14 days post-wounding. |

| Yang et al. 2014 [34] | Original research | Animal | Brain | RT-PCR was used to detect β-APP mRNA. β-APP concentrantion increased between 1 and 6 h in PBSI. |

| Kimura et al. 2015 [35] | Original research | Animal and human | Skin | LC3-II levels decreased, while p62 levels increased in mice with vital wounds when the survival time was longer than 30 min; the PMI did not influence these findings (PMI ranged between 1–4 days). In autoptic samples, LC3-II levels were reduced, while p62 levels increased in controls (PMI tested < 24 h). |

| Birincioğlu et al. 2016 [36] | Original research | Human | Skin | TNF-α was higher in wounded skin than in controls in all age wounds, except in 2–4 h-old lesions. IL-6 was higher in wounded skin than in controls but had statistical significance only when the wound ages were <30 min and >18 h. No statistical significance for other cytokines. |

| Tian et al. 2016 [37] * | Original research | Animal | Skeletal muscle | PAX7 levels increased 1-day post-injury, and the highest level was found at 5 days. MyoD increased after 1 day after the lesion. |

| Wang et al. 2016 [38] | Original research | Animal | Skin | In vital lesions, MCP-1 and CXCL12 increased between 12 h and 5 days after injury. IL-1 β, TNF-α, and pro-col IIIa1 increased 7 days after injury. IL-6 and VEGF-A raised 12 h until 10 days after injury. Procol Ia2 increased from 7 days to 21 days, while IFN decreased between 12 h and 10 days after injury. |

| Peréz et al. 2017 [39] * | Original research | Human | Skin | Fe2+ and Zn2+ concentrations were higher in injured skin than in controls. PMI tested for 19–36 h. |

| He et al. 2018 [40] * | Original research | Animal and human | Skin | No statistical differences in CXCL1 and CXCR2 concentrations between vital lesions and control have been found. |

| Qu et al. 2019 [41] * | Original research | Animal and human | Skin | No statistical differences in ATF3 concentration between vital lesions and control have been found. |

| Peyron et al. 2021 [42] | Original research | Human | Skin | In vital injuries, IL-1β, IL-4, IL-6, IL-10, IL-12p70, IL-13, and TNF-α levels were higher than controls. PMI tested 66.3 +/− 28.3 h. |

| References | Type of Paper | Model | Tissue | Brief Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Betz et al. 1992 [43] | Original research | Human | Skin | Fibronectin + in the skin from a few seconds to 6 weeks after wounding (with a different distribution pattern than control cases). |

| Betz et al. 1993 [44] | Original research | Human | Skin | Fibronectin + in skin lesions from a few minutes after wounding. A1-ACT provides no information. |

| Fieguth et al. 1994 [45] | Original research | Human | Skin | αlact, α2m, and lysozyme showed false + reaction in post-mortem wounds. |

| Betz et al. 1995 [46] | Original research | Human | Skin | Macrophage maturation markers were evaluated. RM 3/1+ cells increase 7 days after wounding, as well as in 7-month-old scar tissue. 25F9+ cells increase 11 days after wounding, as well as in 3-month-old scar tissue. |

| Kondo et al. 1996 [47] | Original research | Animal | Skin | IL-α, IL-ß, IL-6, and TNFα + in 3–6 h-old wounds in neutrophils; by 24 h, they were then substituted by macrophages. TNFα and IL-ß levels increased soon after wounding and peaked at 3 h. IL-α showed a peak at 6 h after wounding, while IL-6 peaked at 12 h after injuring. |

| Dressler et al. 1997 and Dressler et al. 2000 [48,49] | Original research | Human | Skin | ICAM-1 (CD54) strongly + in vital wounded skin, while only slightly + in undamaged skin. The earliest + was at 15 min after wounding, strong + 4 h after wounding, with still + reaction even 10 days after wounding. The distribution of ICAM-1 expression was different between autopsy (PM sampling) and surgical (AM sampling) cases. In autopsy cases, the PMI was ≤7 days. |

| Fieguth et al. 1997 [50] | Original research | Human | Skin | The study aimed to evaluate the influence of post-mortem clamping and autolysis on the IHC reactions by testing antibodies against αlact, α2m, fibronectin, and lysozyme. Autolysis produced an increase in false + reactions, while post-mortem clamping did not. |

| Dressler et al. 1998 [51] | Original research | Human | Skin | P-selectin + from 3 min up to 7 h after wounding, different distribution pattern between autopsy (PM sampling) and surgical (AM sampling) cases. E-selectin + from 1 h up to 17 days after wounding, with a decrease after the 12th hour. L-selectin was not significant. |

| Grellner et al. 1998 [52] | Original research | Animal | Skin | Fibronectin moderately + in wounded areas, whereas in normal skin, both the epidermis and blood vessels showed strong +. |

| Tabata 1998 [53] | Original research | Human | Skeletal muscle | Fibronectin + in muscles when the death occurred immediately after injury and within 2 h after injury. GPA + indicated bleeding in cases of putrefactive changes. Myoglobin (Mb) − reaction in opaque fibers. |

| Dressler et al. 1999 and Dressler et al. 2000 [54,55] | Original research | Human | Skin | VCAM-1 (CD106) strongly + in vital wounded skin, while only slightly + in undamaged skin. Strong + was present from 3 h up to 3.5 days after wounding, with a decrease after the 4th-6th hours. |

| Kondo et al. 1999 [56] | Original research | Human | Skin | At 4 h after wounding, IL-α + neutrophils remained + until 24 h. Neutrophils were substituted by macrophages and fibroblasts, both IL-α +, as skin repair progressed. |

| Grellner et al. 2000 [27] | Original research | Human | Skin | IL-1ß decreased reactivity in surgical samples by 30 min but increased at 2 h after wounding; in autopsy samples, IL-1ß strongly + by 24 h after injury. IL6 strongly + in autopsy samples from 1 h to at least 24 h after injury. TNF-α was strongly + in surgical samples at 1 h after surgery, while in autopsy samples, its levels were higher, between 1 to 24 h. |

| Kondo et al. 2000 [57] | Original research | Human | Skin | c-Fos and c-Jun weak + in neutrophils’ nuclei at 24 h after wounding. In later phases, c-Fos and c-Jun + reactions in macrophages and fibroblasts in granulation tissue. |

| Psaroudakis et al. 2001 [58] | Original research | Animal | Skin | Alkaline phosphatase + at 3.5 h after wounding and peaked at 32 h, nonspecific esterases + at 1 h after wounding and peaked at 24 h and ATPase + at 2 h after wounding and peaked at 20 h. |

| Grellner 2002 [10] | Original research | Human | Skin | IL-1ß + by 15 min, increasing levels were shown at 30–60 min old wounds and remained stable until 8 days postmortem. IL6 + by 20 min after injury; stronger + by 60–90 min until 5 h. TNF-α + reaction after 15 min, strongly + at 60–90 min after wounding. |

| Hausmann et al. 2002 [59] | Original research | Human | Brain | MIB-1 + in cortical contusions in 3 days old wounds and showed an increasing trend until 14 days. Weak + could still be detected 4 weeks post-trauma. |

| Kondo et al. 2002 [60] | Original research | Human | Skin | IL-8, MCP-1, and MIP-1α + neutrophils from 4 to 12 h. IL-8, MCP-1, and MIP-1α cytoplasmic + in macrophages and fibroblasts, granulation tissue formation, and angiogenesis tissue. |

| Kondo et al. 2002 [61] | Original research | Animal and Human | Skin | Animal samples: Ub strongly + neutrophils at 12 h post wounding; between 12 h and 6 days, decreasing levels of neutrophils, while macrophages increased; at day 6, Ub + fibroblasts and macrophages. Human samples: from 4 h to 24 h, Ub + neutrophils cells at the wound site; with increasing wound age, infiltration of macrophages, then fibroblasts. |

| Ortiz-rey et al. 2002 [62] | Original research | Human | Skin and muscle | TN + in the basement membrane of blood vessels and skin appendages, slightly + reaction in the papillary dermis. FN + at the wound edge and adjacent dermis, the prevalence of reticular pattern in vital wounds, rather than in postmortem cases. FN and TN strongly + in hemorrhages both in vital and postmortem samples. |

| Ortiz-rey et al. 2002 [63] | Original research | Human | Skin and muscle | In situ end-labelling technique (Apop-Tag) in 30 human sugical skin injuries with age since injury ranging from 3 min to 8 h and found that apoptotic keratinocytes are found in over 50% of the cases with a post-infliction interval of at least 120 min |

| Bonelli et al. 2003 [64] | Original research | Human | Skin | Tryptase + and chymase + cell (mast cells) densities were higher in vital skin lesions than controls in a time interval < 5 min up to 60 min after wounding. |

| Fieguth et al. 2003 [65] | Original research | Human | Soft tissue | Myoglobin depletion in muscle fibers. Fibronectin strongly + in lymph and blood vessels, as well as damaged skeletal muscle, and areas of hemorrhage. C5b-9 intense staining in sarcolemma fibers and intracellular areas. MRP14 strongly + in perivasal inflammatory infiltrates. |

| Fieguth et al. 2003 [66] | Original research | Human | Skin | Fibronectin was minimally detected in wounds that occurred during immediate fatal trauma, while highly + in areas of active bleeding in immediate fatal wounds. Fibronectin strongly + at 20 min after injury; by 40 min, massive + could be detected. MRP8, MRP14, and defensin + reactions at 20–30 min after wounds occurred could still be demonstrated in 2 to 30 days old wounds. |

| Gauchotte et al. 2003 [67] | Original research | Human | Skin | FVIIIra strongly + in autopsy and surgical samples; putrified samples stained strongly for FVIIIra. CD15 strongly + at wound margins in both autopsy and surgical samples, at a minimum of 9 min after injury. After 7, 14, and 21 days of putrefaction, sensitivity values decreased remarkably. Tryptase + in autopsy and surgical samples. |

| Ortiz-rey et al. 2003 [68] | Original research | Animal | Skin and muscle | FN and TN strongly + reticular staining in vital skin samples from 5 min after wounding to 15 min. Slightly + reaction in postmortem samples. FN and TN weak + in intracellular muscle fibers, but not statistically significant. |

| Hayashi et al. 2004 [69] | Original research | Human | Skin | VEGF negative reaction until 24 h after wounding, with increasing wound age VEGF + cytoplasm of mononuclear cells and fibroblastic cells, around CD31 + neovessels. |

| Balažic et al. 2005 [70] | Original research | Human | Skin | Fibronectin + in head gunshot skin in cases of a longer survival time, weaker + when the survival time was extremely short. |

| Bacci et al. 2006 [71] | Original research | Human | Skin | TNF-α + (mast cells) from 15 min after wounding was significatively more intensive than controls. |

| Tarran et al. 2006 [72] | Original research | Human | Skin | In post-mortem samples, neutrophil elastase + from 12 h to 7 days, CD68 + from day 2 to day 28, and CD45 + (lymphocytes) from day 35 to day 77. |

| Takamiya et al. 2007 [73] | Original research | Human | Skin | Neutrophil elastase and CD68 + (macrophages) from 2 h post-injury, peaking at 33–49 h, while CD3 + (lymphocytes B) from 71 h and vimentin + (fibroblasts) from 246 h. TNF-α+ from 30 min, peaked at 9 h after wounding. IL10, GM-CSF, and IFN-γ + from 2 h after injury, with peaks, respectively, at 71–116 h, 33–49 h, and 12–15 h. IL6, IL8, and IL2 + peak at 9 h. IL4+ peak at 33–49 h. |

| Takamiya et al. 2007 [74] | Original research | Animal | Brain | 27 different cytokines expression in different phases of cerebral wound healing. IL12 p40, IL18, bFGF, KC, M-CSF, MIG, MIP-1α, and PDGF BB were strongly expressed after cerebral stab wounds in mice. |

| Ishida et al. 2008 [75] | Original research | Human | Skin | ORP150 + mononuclear and fibroblastic cells at 24 h after wounding. ORP150 + non-enhanced in PM inflicted wounds. |

| Ortiz-Rey et al. 2008 [76] | Short communication | Human | Skin | CD31 + in endothelial cells, P-selectin + reaction in small blood vessels adjacent to the vital wound edge. P-selectin and CD31 weakly + in PM wounds and presence of background artifact or tissue disruption. |

| Neri et al. 2009 [77] | Original research | Human (liveborn and stillborn fetuses) | Umbilical cords | Tryptase (mast cells), α1-antichymotrypsin, and CD68 were strongly + in umbilical cords of liveborn fetuses, while weakly reactive in stillborn. Among stillborn fetuses, CD68 + was higher in perinatal deaths during prolonged labor than intrauterine deaths. |

| Nogami et al. 2009 [78] | Original research | Animal | Skin | Podoplanin + vessels absence at 1, 3, 7, 28, 56, and 84 days after incision. From day 5 to 7, CD31+ vascular vessels with a mainly vertical course; after 14 days, CD31+ vascular vessels result to be less vertical; by day 28, became similar to vessels in control skin areas. In paraffin sections, vWF + lymphatic vessels in wound areas and absence of podoplanin + vascular vessels. |

| Oehmichen et al. 2009 [79] | Original research | Human | Brain | CD68 + macrophages in cortical hemorrhages at 3 h PTI, CD68 weak + in the adjacent cortex at 12 h PTI, strongly + by 60 h PTI, peak at day 10 PTI. HLA-D + macrophages at 6 h PTI in hemorrhages, peak at day 12. HAM-56 reactive macrophages within 31 h PTI, increasing up to day 11. LN-5 + macrophages in hemorrhagic areas detect at 24 h PTI, strongly + on day 5. 25F9 slightly + macrophages within 100 h PTI |

| Bohnert et al. 2010 [80] | Original research | Human | Lung | Fibronectin + in the lung tissue of burned corpses (intravital fire exposure) was more intensive than controls. |

| Cattaneo et al. 2010 [81] | Original research | Human | Bone | GPA + in vital bone fractures, survival time ranged from 34 min to 26 days. |

| Jin et al. 2010 [82] | Original research | Animal | Oral mucosa | TNF-α strongly + on day 3 after surgery, decreasing by day 5–7, TNF-α+ neutrophils on day 1 to 3, and fibroblasts on day 14 post-surgery. TGF-ß1 levels decreased on day 5 after surgery and then increased until day 14. |

| Guler et al. 2011 [83] | Original research | Human | Skin | Tenascin strongly + in all types of wounds investigated, by 24 h after injury. Weak + of ubiquitin since 24 h after wounding, still present in wounds over 40 days old, while tenascin was negative. |

| Ryu et al. 2011 [84] | Original research | Animal | Oral mucosa | TNF-α+ 1-day post-surgery in scalpel wounds and 3 days post-surgery in laser wounds, reaching its peak at day 3 for all groups of surgery. TNF-ß + levels increased 3 days post-surgery, decreased until day 7, and increased further until day 14 both in laser and scalpel wounds. The highest intensity is shown at day 3. |

| Taborelli et al. 2011 [85] | Original research | Human | Skin | GPA+ at day 3, 6, and 15 PM, negativity after day 30, in putrefied specimens in air, while histological techniques were no longer useful by day 15. GPA + on day 3 and day 6 in putrefied specimens in water, while histological techniques were no longer useful by day 6. |

| Capatina et al. 2012 [86] | Case report | Human | Skin and liver | Fibronectin + in the skin and liver samples, suggesting vital lesions. P-selectin and tenascin-X were negative/irrelevant. |

| Cecchi et al. 2012 [87] | Case report | Human | Skin | P-selectin + in wounded skin, while E-selectin was negative. The authors concluded the survival time was less than 30–60 min. |

| Ishida et al. 2012 [88] | Original research | Human | Skin | MPO, and COX2 + neutrophils at wound sites from 2 h to 2 days after injury. In 3-day-old specimens, CD68 + macrophages were present and reactive for COX2 and pAbs. |

| Zheng et al. 2012 [89] | Original research | Animal | Skin | CB2R + from 1 to 12 h in PMNs on days 1 and 3 in round-shaped MNCs, as well as in FBCs from day 5. Decreased + from day 14 in MNCs, and day 21 in FBCs. |

| Capatina et al. 2013 [90] | Original research | Human | Skin | Fibronectin and P-selectin + in skin lesions with a short survival time. The PMI did not influence their expression. |

| Agha et al. 2013 [91] | Original research | Animal | Skin | iNOS and VEGF + in wounded skin. iNOS started after 6 h, peaked on day 1, still + on day 10 after wounding. Weak iNOS + also in normal skin. VEGF started from day 1, strong + from day 3 to 10 after wounding. |

| Akbaba et al. 2014 [92] | Original research | Animal | Skin | Ki-67 + in the skin from day 1 to day 5 after wounding. Ubiquitin + from >24 h up to 7 days after wounding. |

| Bacci et al. 2014 [93] | Original research | Human | Skin | MHC-II+ and CD1a+ cells increase in the epidermis after wounding, the MHC-II+/CD1a+ cells ratio was lower than controls within 30 min, then higher from 30 min up to 24 h after wounding. In the dermis, MHC-II+ cells increase between 31 and 60 min after wounding, while DC-SIGN+ and CD11c+ cells were seen at the periphery of infiltrates and in the basal epidermal layer. |

| Cecchi et al. 2014 [94] | Original research | Human | Lung | SP-A massive + in intra-alveolar deposits in cases of intense hypoxic stimulus. HIF1-α + in vessels in cases of hypoxia, the intensity was proportional to the duration of the hypoxic stimulus. |

| Fan et al. 2014 [33] * | Original research | Animal | Skeletal muscle | Slight α7nAChR + in sarcolemma and sarcoplasm of undamaged myofibers. Presence of α7nAChR + PMNs, macrophages, and myofibroblasts in contused skin, starting from 1–3 h after contusion (only a few cells), increasing from the 12th hour, peaking at day 7, and gradually reducing within the 14th day after wounding. |

| Kubo et al. 2014 [95] | Original research | Animal and Human PM | Skin | AQ3 + keratinocytes in the area surrounding burned skin, similarly to control samples. No difference in the expression of AQ3 between ante- and post-mortem burned skins. |

| Montisci et al. 2014 [96] | Original research | Human | Skin | Cath-D + in both surgical and PM samples is homogeneous in different sampling timing. From 30 min after injury, Cath-D is strongly + in surgical samples. |

| Van de Goot et al. 2014 [97] | Original research | Human | Skin | Fibronectin, CD62, and Factor VIII strongly + in wounds that occurred a few minutes before death, these markers + increased in 30-min-old wounds. |

| Balandiz et al. 2015 [4] | Original research | Animal | Skin | IL-1β+ cells in the epidermis from 2 h (peak) up to 72 h from hanging (putrefactive phenomena independent). |

| Capatina et al. 2015 [98] | Case report | Human | Skin | Fibronectin and P-selectin + reaction in skin wounded 1 h after death (only post-mortem lesions). |

| El Deeb et Badr El Dine 2015 [99] | Original research | Animal | Skin | mAb D2–40 (lymphatic endothelium marker, it reacts with M2A antigen) + in the peripheral granulation tissue, edge, and deep of the wound. Positivity ranged from day 3 to day 7 in sutured wounds, from day 5 to day 10 in wounds that were not sutured. |

| Fronczek et al. 2015 [100] | Original research | Human | Skin | Neutrophilic granulocytes peaked at 0.2 to 2 days after injury and declined gradually in time. CD45 + lymphocytes peaked at 0.2 to 2 days and declined by day 10 after wounding. CD68 + macrophages peaked at days 2 to 4 after injury and declined gradually in time. MIP-1, and IL8 + from 0.2 to 2 days old wounds; NεCML strongly + at 0.2 to 2 days old wounds, decreasing by day 4 to 10, then increasing in wounds older than 10 days. |

| Ishida et al. 2015 [101] | Original research | Animal | Skin | CD34 and Flk-1 + EPCs cells accumulate at wound sites, while scarcely detected in unwounded skin tissue samples |

| Kara et al. 2016 [102] | Original research | Animal | Skin | Collagen I and Collagen III + fibroblasts, and VEGF + inflammatory cells, at 3 h after wounding, decreasing by 6 and 24 h. E-selectin and fibronectin + fibroblasts, strongly reactive by 1 h after injuring until 24 h. IL-α+ fibroblasts were statistically significant at 3 h and maintained until 24 h. P-selectin and TGF-ß1 + inflammatory cells in the 1-h-old wound. |

| Yu et al. 2016 [103] | Technical note | Animal | Skeletal muscle | MMP-2 and TIMP-2 + in PMNs from 6 to 24 h after injury in the skeletal muscle, and MNCs in the contused zones. From day 3, MMP-2 intense + in centronucleated myotubes. MMP-2 and TIMP-2 + were also found in endothelial cells of new vessels. |

| Abo El-Noor et al. 2017 [104] | Original research | Animal | Skin | iNOS + in burned skin. Starting from day 1, peak at day 7, declining from day 9. |

| Ji et al. 2017 [105] | Original research | Animal | Skin | RAGE + PMNs from 6 to 12 h after wounding, RAGE + MNCs from day 1 to 3 post-injury, and day 5 post-wounding RAGE reactivity primarily in MNCs and fibroblasts. |

| Legaz et al. 2017 [106] | Original research | Human | Skin | Cathepsin D moderative or strongly + cells in skin wounds of ligature marks. Cathepsin D and P-selectin moderately + cells in skin wounds with subcutaneous injury, rather than subcutaneous and muscular injury. |

| Murase et al. 2017 [107] | Original research | Animal | Skin | Chil3 + cells from day 1 to day 9 after wounding. From day 2, presence of two types of + cells, a small oval one and large elongated one. |

| Doberentz et Madea 2018 [108] | Case series | Human | Heart, lung, and kidney | Heart, lung, and kidney samples were HSP27 and HSP70 negative in two burned-after-death corpses. Renal tissue was moderately + for HSP27 reaction, while negative for HSP70, in a case of death with immediate burning (bomb explosion). The authors considered the HSP27 expression a supravital phenomenon. |

| Ishida et al. 2018 [109] | Original research | Human | Skin | AQ1 weakly + at day 2 after injury, by day 3 to 14 was detected a stronger + to AQ1. AQ3 weakly + in wounds from 3 to 14 days old. |

| Ishida et al. 2018 [8] | Original research | Human | Skin | AQ1 + in dermal capillaries of ligature marks, while AQ3 was primarily expressed in keratinocytes of ligature marks. |

| Legaz Pérez et al. 2018 [39] * | Original research | Human | Skin | Fibronectin + in basement membranes and interstitial connective tissue of ligature wounds. Cathepsin D + in skin wounds of hanging marks while P-selectin showed weaker + reaction in vital wounds compared to normal skin. |

| Metwally et al. 2018 [110] | Original research | Human | Skin | Decreasing intensity of both P-selectin (CD62p) and fibronectin as the PM interval increases until 12 h. CD62p and fibronectin increased intensity from 30 min to 90 min after injury in AM samples. |

| De Matteis et al. 2019 [111] | Original research | Human | Skeletal muscle | Intracytoplasmic depletion of troponin I in neck muscle fibers in cases of suicidal hanging. |

| Focardi et al. 2019 [112] | Original research | Human | Skin | MHC-II + dendritic cells were significantly higher in ligature marks and vital lesions. CD1a + Langerhans cells were higher in vital lesions and ligature marks, as well. |

| Khalaf et al. 2019 [113] | Original research | Animal | Skin | α-SMA and VEGF negative to mild expression at 0, 1, and 3 days after wounding. CD68 + macrophages from day 3 at the wound surface, peaking at day 7, and declining by day 14. α-SMA was still strongly expressed by day 14. |

| Focardi et al. 2020 [114] | Original research | Human | Skin | iNOS + Langherans cells were higher in ligature marks than other samples groups. iNOS + mast cells in vital wounds and hanging furrows. MHC + mast cells were highly expressed in the sulcus, while barely visible in vital wounds, controls, or post-mortem wounds. |

| Maiese et al. 2020 [115] | Original research | Human | Skin | Intracytoplasmic depletion of FLIP in epidermal layers, with epidermal flattening, in subjects who died by hanging. |

| Baldari et al. 2021 [116] | Original research | Human | Bone and soft tissues | GPA + in vital bone fracture and wounded soft tissues in corpses at different putrefactive stages (PMI range 2–187 days). |

| Bertozzi et al. 2021 [117] | Original research | Human | Skin and soft tissues | Tryptase, GPA, IL15, CD15, CD45, and MMP9 + in vital wounded putrefied skin (PMI < 15 days) with a differential time expression, according to the PMI. |

| Niedecker et al. 2021 [118] | Original research | Animal and human | Muscle and myocardium | Human skeletal muscle stained MMP-9 and MMP-2 + from a few minutes after the injury to 12 h, and TIMP-1 + from a few minutes to 4 h. MMP-9, TIMP-1, and MMP-2 were strongly + in human myocardium injuries from a few minutes to 4 h. TIMP-1 negativity in rats’ heart postmortem inflicted wounds. |

| Peyron et al. 2021 [42] * | Original research | Human | Skin | IL-8 + cells in five vital skin wounds, while no IL-8 + cells in the controls. |

| Prangenberg et al. 2021 [119] | Original research | Human | Skin | AQ3 strongly + in injured epidermis, independent of kind of injury, while slightly + in uninjured skin. |

| Wegner et al. 2021 [120] | Case report | Human | Kidney, lung, and skin | The study described only two cases. In the first case, the body was found in a sauna after 3 days. AQ3 + in the epidermis, HSP 27, HSP 60, and HSP70 were not detectable in kidneys or lungs. In the second case, the body was found in a sauna after about 35 min, with HSP 27, HSP 60, and HSP 70 + in preserved lung and kidney tissue. |

| Khismatullin et al. 2019 [121] | Original research | Human | Blood clot | Picro-Mallory staining determines different fibrin color depending on clots formation timing. At 30 minutes to 6 h of maturation, fibrin stained red, from 6 to 12 h fibrin was purple or violet while in old clots, incubated 24 to 48 h, fibrin stained blue. |

| Zamboni et al. 2004 [122] | Original research | Human | Skin | FXIII positive effects against MMPs action on fibroblasts cultures, enhancing wound healing. |

| Messenger RNA | ||||

| References | Type of Paper | Model | Tissue | Brief Description |

| Ohshima et al. 1998 [121] | Original research | Animal | Skin | IL-10 mRNA increased at 15 min after injury, peaked at 60 min, and maintained an increase until 5 days. |

| Sato et al. 2000 [122] | Original research | Animal | Skin | IL-6 mRNA peaked at 6 h after injury. IL-1α, IL-1β, and TNFα peaked between 48 and 72 h after injury. |