The Development of the CAIRDE General

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Development Framework

2.2. Identifying the Evidence Base

2.3. The Stepwise Development Process

2.3.1. Development Cycle 1: Design of the Initial Training Draft

2.3.2. Develop Program Theory

2.3.3. Consider Context

2.3.4. Engage Stakeholders and Identify Uncertainties

2.3.5. Co-Design Round 1

2.4. Development Cycle 2: Reviewing and Refining the Training for Delivery

Co-Design Round 2

3. Results

3.1. Modeling Processing and Outcomes

3.2. Intervention Components

3.3. Validating the Delivered Training

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Windsor-Shellard, B.; Gunnell, D. Occupation-specific suicide risk in England: 2011–2015. Br. J. Psychiatry 2019, 215, 594–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donnell, S.; Egan, T.; Clarke, N.; Richardson, N. Prevalence and associated risk factors for suicidal ideation, non-suicidal self-injury and suicide attempt among male construction workers in Ireland. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, S.E.; Jaremin, B.; Lloyd, K. High-risk occupations for suicide. Psychol. Med. 2013, 43, 1231–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tyler, S.; Gunn, K.; Esterman, A.; Clifford, B.; Procter, N. Suicidal Ideation in the Australian Construction Industry: Prevalence and the Associations of Psychosocial Job Adversity and Adherence to Traditional Masculine Norms. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milner, A.J.; Niven, H.; LaMontagne, A.D. Occupational class differences in suicide: Evidence of changes over time and during the global financial crisis in Australia. BMC Psychiatry 2015, 15, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.S.; Brooks, R.D.; Brown, S.; Harris, W. Psychological distress and suicidal ideation among male construction workers in the United States. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2022, 65, 396–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, I.; Petrie, K.; Einboden, R.; Collins, D.; Ryan, R.; Johnston, D.; Harvey, S.B.; Glozier, N.; Wray, A.; Deady, M. Apprentices’ Attitudes Toward Using a Mental Health Mobile App to Support Healthy Coping: Mixed Methods Study. JMIR Hum. Factors 2022, 9, e35661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einboden, R.; Choi, I.; Ryan, R.; Petrie, K.; Johnston, D.; Harvey, S.B.; Glozier, N.; Wray, A.; Deady, M. ‘Having a thick skin is essential’: Mental health challenges for young apprentices in Australia. J. Youth Stud. 2021, 24, 355–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyler, S.; Gunn, K.; Clifford, B.; Procter, N. “And you feel like you’re suffocating … how the fuck am I going to get out of all this?” Drivers and experiences of suicidal ideation in the Australian construction industry. Front. Psychiatry 2023, 14, 1144314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, V.; Caton, N.; Gullestrup, J.; Kõlves, K. Understanding the Barriers and Pathways to Male Help-Seeking and Help-Offering: A Mixed Methods Study of the Impact of the Mates in Construction Program. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connell, R.W.; Messerschmidt, J.W. Hegemonic Masculinity: Rethinking the Concept. Gend. Soc. 2005, 19, 829–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Considine, R.; Tynan, R.; James, C.; Wiggers, J.; Lewin, T.; Inder, K.; Perkins, D.; Handley, T.; Kelly, B. The Contribution of Individual, Social and Work Characteristics to Employee Mental Health in a Coal Mining Industry Population. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0168445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roche, A.M.; Pidd, K.; Fisher, J.A.; Lee, N.; Scarfe, A.; Kostadinov, V. Men, Work, and Mental Health: A Systematic Review of Depression in Male-dominated Industries and Occupations. Saf. Health Work 2016, 7, 268–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, V.; Mathieu, S.; Wardhani, R.; Gullestrup, J.; Kõlves, K. Suicidal ideation and related factors in construction industry apprentices. J. Affect. Disord. 2022, 297, 294–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.Y.; Hwang, J.; Ball, J.G.; Lee, J.; Yu, Y.; Albright, D.L. Mental Health Literacy Affects Mental Health Attitude: Is There a Gender Difference? Am. J. Health Behav. 2020, 44, 282–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, L.J.; Goldney, R.D. Differences in community mental health literacy in older and younger Australians. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2002, 18, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, T.L.; Batterham, P.J.; Lingard, H.; Gullestrup, J.; Lockwood, C.; Harvey, S.B.; Kelly, B.; LaMontagne, A.D.; Milner, A. Are young men getting the message? age differences in suicide prevention literacy among male construction workers. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duckworth, J.; Hasan, A.; Kamardeen, I. Mental health challenges of manual and trade workers in the construction industry: A systematic review of causes, effects and interventions. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2024, 31, 1479–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaac, M.; Elias, B.; Katz, L.Y.; Belik, S.-L.; Deane, F.P.; Enns, M.W.; Sareen, J. Gatekeeper Training as a Preventative Intervention for Suicide: A Systematic Review. Can. J. Psychiatry 2009, 54, 260–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gould, M.S.; Cross, W.; Pisani, A.R.; Munfakh, J.L.; Kleinman, M. Impact of Applied Suicide Intervention Skills Training on the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline. Suicide Life-Threat. Behav. 2013, 43, 676–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, G.; Clacy, A.; Hermens, D.F.; Lagopoulos, J. The Long-Term Efficacy of Suicide Prevention Gatekeeper Training: A Systematic Review. Arch. Suicide Res. 2019, 24, 177–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gullestrup, J.; King, T.; Thomas, S.L.; LaMontagne, A.D. Effectiveness of Australian MATES in Construction Suicide Prevention Program: A systematic Review. Health Promot. Int. 2023, 38, daad082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, C.; Gringart, E.; Strobel, N. Explaining adults’ mental health help-seeking through the lens of the theory of planned behavior: A scoping review. Syst. Rev. 2022, 11, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, S.; Atkins, B.; Kellar, I.; Taylor, J.; Keevil, V.; Alldred, D.P.; Murphy, K.; Patel, M.; Witham, M.D.; Wright, D.; et al. Co-design of a behaviour change intervention to equip geriatricians and pharmacists to proactively deprescribe medicines that are no longer needed or are risky to continue in hospital. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2023, 19, 707–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillam, J.; Evans, C.; Aworinde, J.; Ellis-Smith, C.; Ross, J.; Davies, N. Co-design of a theory-based implementation plan for a holistic eHealth assessment and decision support framework for people with dementia in care homes. Digit. Health 2023, 9, e20552076231211118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waddell, A.; Spassova, G.; Sampson, L.; Jungbluth, L.; Dam, J.; Bragge, P. Co-designing a theory-informed intervention to increase shared decision-making in maternity care. Health Res. Policy Syst. 2023, 21, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letts, A.; Knight, K.; Halliday, D.; Singleton, J. Using the Behaviour Change Wheel and Theoretical Domains Framework in the Co-Design of a Recycling Intervention Implemented in a Rural Australian Public Hospital. Res. Sq. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Skivington, K.; Matthews, L.; Simpson, S.A.; Craig, P.; Baird, J.; Blazeby, J.M.; Boyd, K.A.; Craig, N.; French, D.P.; McIntosh, E.; et al. A new framework for developing and evaluating complex interventions: Update of Medical Research Council guidance. Br. Med. J. 2021, 374, n2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damghanian, M.; Alijanzadeh, M. Theory of Planned Behavior, Self-Stigma, and Perceived Barriers Explains the Behavior of Seeking Mental Health Services for People at Risk of Affective Disorders. Asian J. Soc. Health Behav. 2018, 1, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roche, E.; Richardson, N.; Sweeney, J.; O’Donnell, S. Workplace Interventions Targeting Mental Health Literacy, Stigma, Help-Seeking, and Help-Offering in Male-Dominated Industries: A Systematic Review. Am. J. Men’s Health 2024, 18, e15579883241236223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sweeney, J.; O’Donnell, S.; Roche, E.; White, P.J.; Carroll, P.; Richardson, N. Mental Health Stigma Reduction Interventions Among Men: A Systematic Review. Am. J. Men’s Health 2024, 18, e15579883241299353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roche, E.; O’Donnell, S.; Richardson, N. “You Have to Make It Normal, That’s What We Do”: Construction Managers’ Experiences of Help-Offering. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, P.; Dieppe, P.; Mcintyre, S.; Michie, S.; Nazareth, I.; Peticrew, M. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: The new Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ 2008, 337, a1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Cathain, A.; Croot, L.; Duncan, E.; Rousseau, N.; Sworn, K.; Turner, K.M.; Yardley, L.; Hoddinott, P. Guidance on how to develop complex interventions to improve health and healthcare. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e029954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, T.; Wilson, C.J.; Caputi, P.; Woodward, A.; Wilson, I. Signs of current suicidality in men: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0174675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drew, R.J.; Morgan, P.J.; Pollock, E.R.; Young, M.D. Impact of male-only lifestyle interventions on men’s mental health: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes. Rev. 2020, 21, e13014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lynch, L.; Long, M.; Moorhead, A. Young Men, Help-Seeking, and Mental Health Services: Exploring Barriers and Solutions. Am. J. Men’s Health 2016, 12, 138–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richardson, N.; Carroll, P. It’s Not Rocket Science: The Case from Ireland for a Policy Focus on Men’s Health. Int. J. Men’s Soc. Community Health 2018, 1, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammersley, C.; Richardson, N.; Meredith, D.; McNamara, J.; Carroll, P.; Jenkins, P. ‘On Feirm Ground’: Analysing the effectiveness of a bespoke farming mental health training programme targeted at farm advisors in Ireland. J. Agric. Educ. Ext. 2024, 31, 90–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborne, A.; Carroll, P.; Richardson, N.; Doheny, M.; Brennan, L.; Lambe, B. From training to practice: The impact of ENGAGE, Ireland’s national men’s health training programme. Health Promot. Int. 2018, 33, 458–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, T.C.; Glasziou, P.P.; Boutron, I.; Milne, R.; Perera, R.; Moher, D.; Altman, D.G.; Barbour, V.; Macdonald, H.; Johnston, M.; et al. Better reporting of interventions: Template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ 2014, 348, g1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gullestrup, J.; Thomas, S.; King, T.; LaMontagn, A.D. The role of social identity in a suicide prevention programme for construction workers in Australia. Health Promot. Int. 2024, 39, daae140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biswajit, P.; Kirubakaran, R.; Isacc, R.; Dozier, M.; Grant, L.; Weller, D. A systematic review of the theory of planned behaviour interventions for chronic diseases in low health-literacy settings. J. Glob. Health 2023, 13, 04079. [Google Scholar]

- Mangurian, C.; Niu, G.C.; Schillinger, D.; Newcomer, J.W.; Dilley, J.; Handley, M.A. Utilization of the Behavior Change Wheel framework to develop a model to improve cardiometabolic screening for people with severe mental illness. Implement. Sci. 2017, 12, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Theory of Planned Behavior | Co-Design Section | Key Uncertainties and Issues to be Addressed | Training Content Post Co-Design Workshop 1 | Finalized Content of Training Post Co-Design Workshop 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attitudes—a person’s favorable or unfavorable evaluation of the problem (mental health) and/or behavior (help-seeking) | Perception about the Problem | 1.1 Introduction | 1.1 Introduction | |

| Attitudes—a person’s favorable or unfavorable evaluation of the problem (mental health) and/or behavior (help-seeking) | Perception about the Problem | Illness recognition

| 2.1. Suicide among men 2.2. Suicide and mental health issues among construction workers 2.3. Causes and risk factors of suicide among construction workers | 2.1. Suicide among men 2.2. Suicide and mental health issues among construction workers 2.3 Impact of Suicide 2.4. Causes and risk factors of suicide among construction workers |

Perceived susceptibility

| 2.2. Suicide and mental health issues among construction workers | 2.2. Suicide and mental health issues among construction workers | ||

Recognition of symptoms

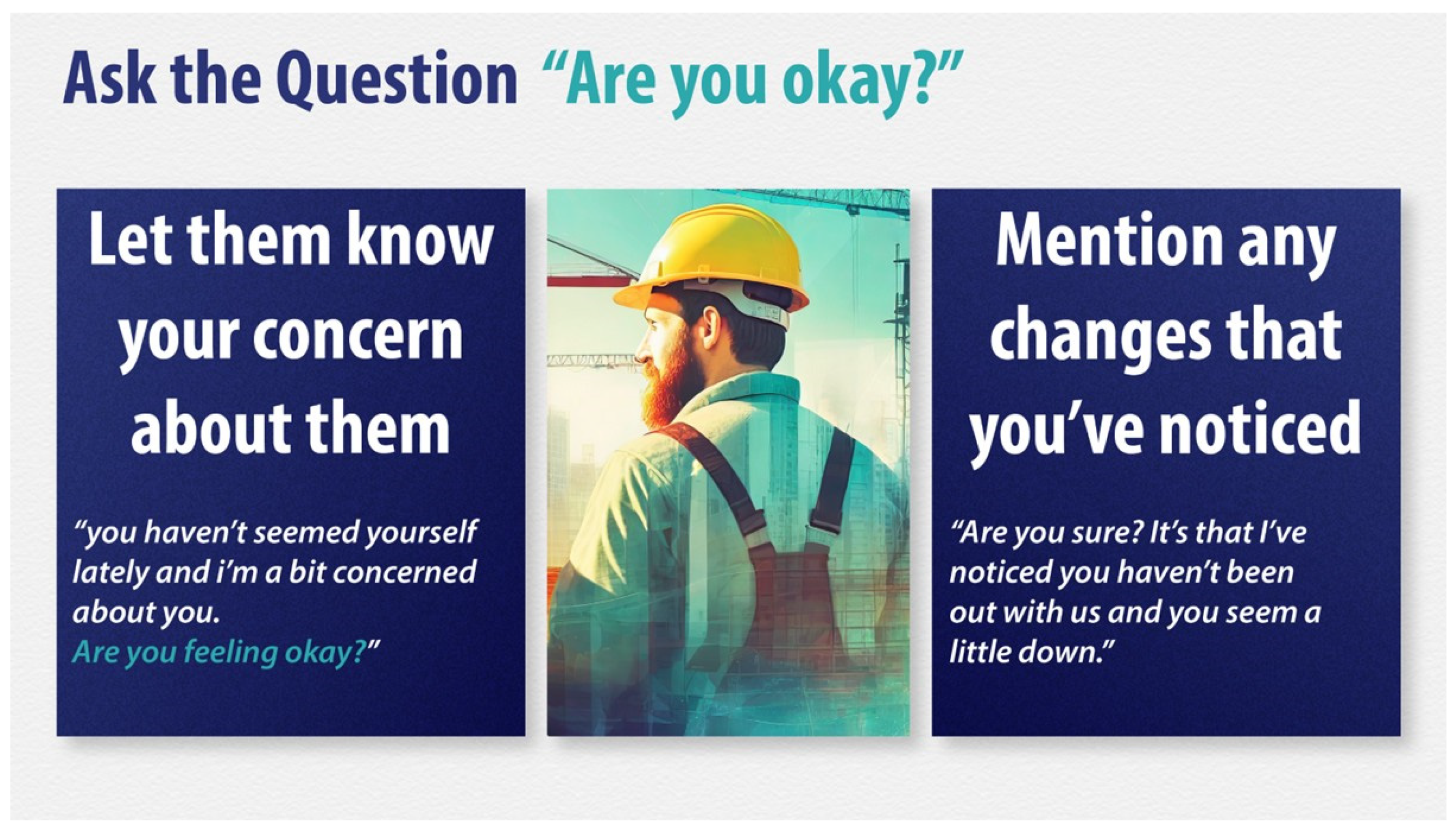

| 4.1. Know the signs | 4.3. Know the signs | ||

Perceived severity of symptoms

| 2.4. The ‘Big Build’ | 4.3. Know the signs | ||

Beliefs about preventability

| 3.1. Preventability of suicide—Dispelling myths | 3.1. Preventability of suicide—Dispelling myths | ||

Personal stigma of suicide

| 3.1. Preventability of suicide—Dispelling myths | 3.1. Preventability of suicide—Dispelling myths | ||

| Perception about Support | Evaluation of the helper

| 3.2. Value, need, and importance of timely help | 3.2. Value, need, and importance of timely help | |

Perceived value of help

| 3.2. Value, need, and importance of timely help | 3.2. Value, need, and importance of timely help | ||

Perceived need for help

| 3.2. Value, need, and importance of timely help | 3.2. Value, need, and importance of timely help | ||

| Openness/willingness to accept help | 3.3. Challenging stigma of suicide and help-seeking (reframing) | 3.4. Challenging stigma around suicide and help-seeking (reframing) | ||

Knowledge of available supports

| 4.2. Know the available services | 4.2. Know the available services and support pathways | ||

| Other | Self-stigma

| 3.3. Challenging stigma around suicide and help-seeking (reframing) | 3.3. Challenging stigma around suicide and help-seeking (reframing) | |

Pros/cons of disclosure

| 3.2. Value, need, and importance of timely help | |||

Ability to communicate emotions

| 3.3 Providing examples of conversation starters and emotional language | |||

| Social norms—a person’s beliefs about whether others approve or disapprove of help-seeking for mental health. Consists of a person’s evaluation of normative beliefs and their motivation to comply with others. | Willingness to communicate | Social norms—masculinities, mental health, and help-seeking

| 3.3. Challenging stigma around suicide and help-seeking (reframing) | 3.4. Challenging stigma around suicide and help-seeking (reframing) |

| Perceived behavioral control—a person’s perceived resources, skills, and opportunities to seek help for mental health problems. | Self-efficacy | Confidence to seek help | Addressed throughout training | Addressed throughout training |

| Controllability | Perceived control over behavior | 4.2. Know the available services | 4.2. Know the available services | |

| Physical barriers (time, cost, availability) | Not addressed | 3.5 What are the options | ||

| Physical opportunities | 4.2. Know the available services | 4.2. Know the available services |

| Brief Name | |

|---|---|

| 1 | General Awareness Training (CAIRDE) |

| Why | |

| 2 | The training was developed to reduce suicide rates among construction workers in Ireland. It aims to reduce mental health and suicide stigma, improve mental health literacy, and increase intentions to both seek and offer help. |

| What | |

| 3 | The training is primarily psychoeducational. The main resources include a 40-page facilitator’s pack and PowerPoint presentations. Three integrated video resources include: (1) a personal story based on a selection of the lived experiences of construction workers, taken from the focus groups and co-design workshops, and portrayed by an actor; (2) interviews showcasing examples of help-offering within the construction industry; and (3) information on resources and supports available from General Practitioners (GPs) and other mental health support services. Participants also receive wallet cards developed by the National Office for Suicide Prevention (NOSP), which list contact details for support services for those experiencing mental health difficulties or a mental health crisis. |

| 4 | Participants are gathered in a meeting room and introduced to the training. It starts with an ice-breaker about participants’ professions, followed by the main content. An interactive “true or false” segment on mental health and suicide myths is included. At the end, support resources are shared along with the NOSP wallet cards. |

| Who Provided | |

| 5 | The training is delivered by a professional mental health training facilitator from the Health Service Executive (HSE). |

| How | |

| 6 | The training is conducted in person, face to face, in sessions lasting approximately one hour, with up to 30 participants per session. |

| Where | |

| 7 | The training is delivered at construction sites, typically in induction training rooms equipped with a projector or large display. |

| When and How Much | |

| 8 | The training is a once-off, hour-long session provided free of charge. |

| Tailoring | |

| 9 | The training is specifically designed for the construction industry in Ireland, incorporating culturally relevant references and appropriate language. |

| How Well | |

| 10 | The training’s effectiveness will be assessed during pilot delivery using the LOSS (Literacy of Suicide Scale), SOSS (Stigma of Suicide Scale), and GHSQ (General Health Seeking Questionnaire) to measure changes in mental health and suicide literacy, stigma, and help-seeking intentions. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sweeney, J.; Richardson, N.; Carroll, P.; White, P.J.; Roche, E.; O’Donnell, S.

The Development of the CAIRDE General

Sweeney J, Richardson N, Carroll P, White PJ, Roche E, O’Donnell S.

The Development of the CAIRDE General

Sweeney, Jack, Noel Richardson, Paula Carroll, P. J. White, Emilie Roche, and Shane O’Donnell.

2025. "The Development of the CAIRDE General

Sweeney, J., Richardson, N., Carroll, P., White, P. J., Roche, E., & O’Donnell, S.

(2025). The Development of the CAIRDE General