A Train-the-Trainer Approach to Build Community Resilience to the Health Impacts of Climate Change in the Dominican Republic

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Train-the-Trainer Program

2.2. Community Training

2.3. Recruitment and Enrollment

2.4. Survey and Evaluation

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

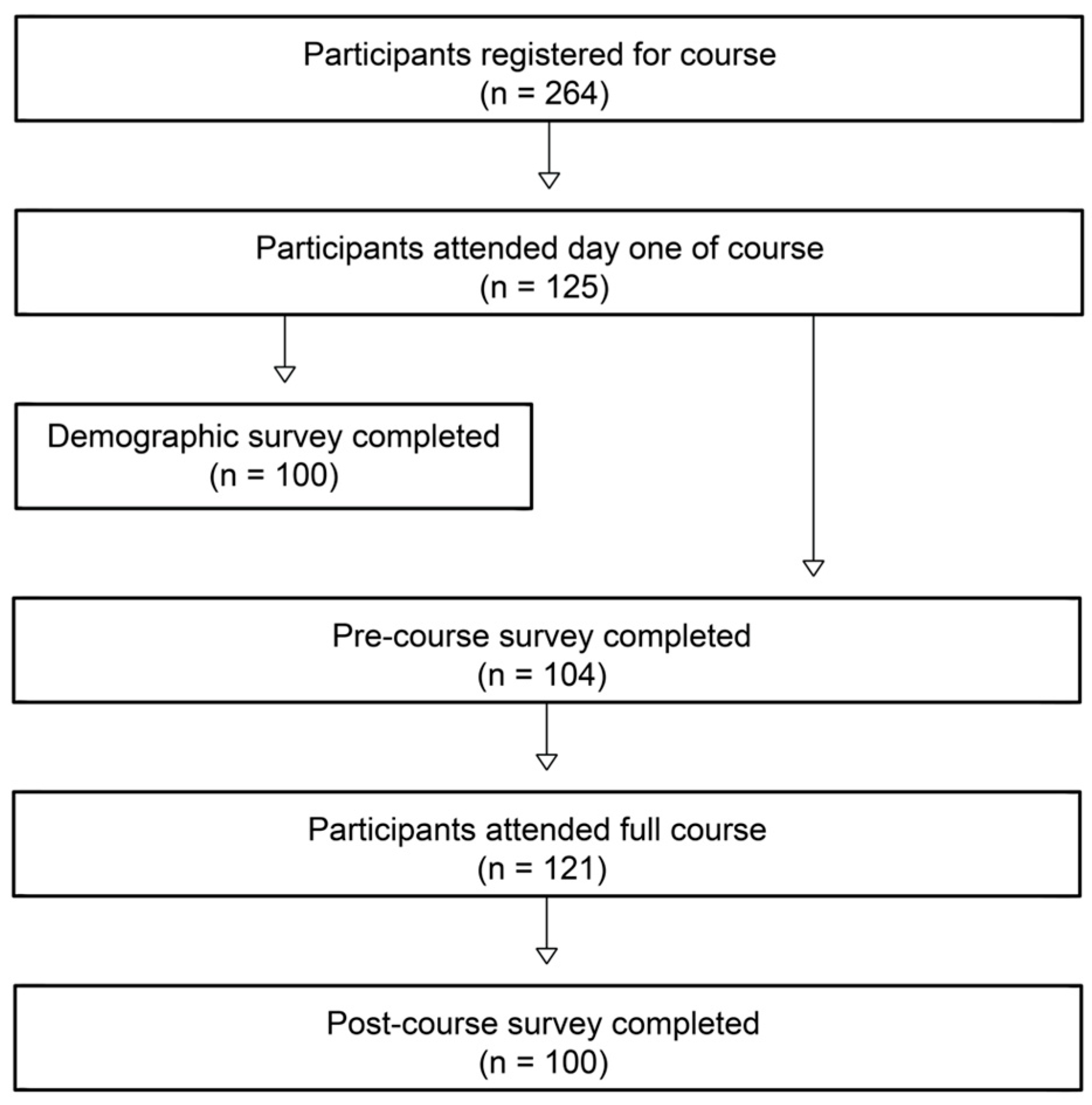

3.1. Demographics and Participation

3.2. Climate Change Knowledge and Awareness

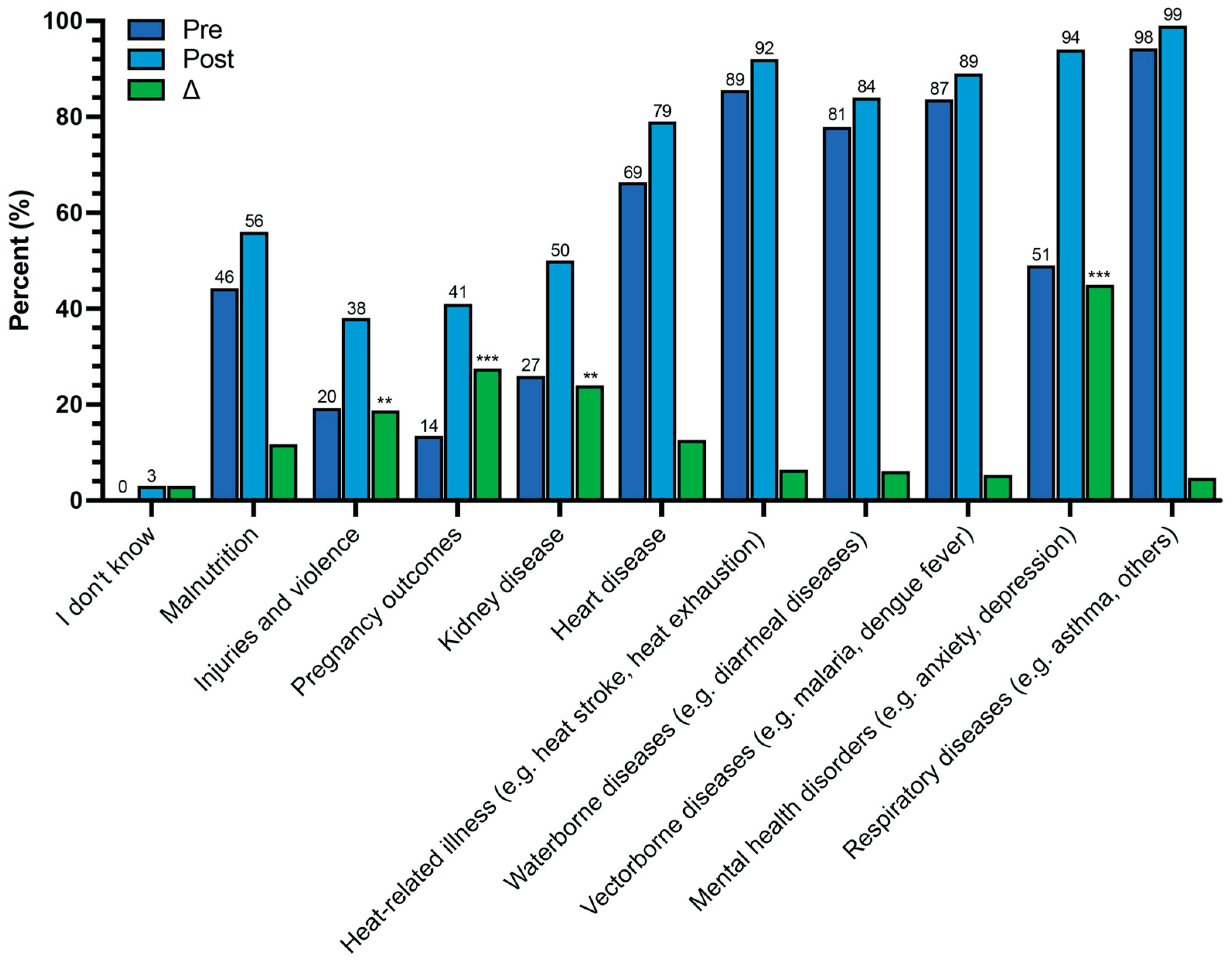

3.3. Climate Change Literacy

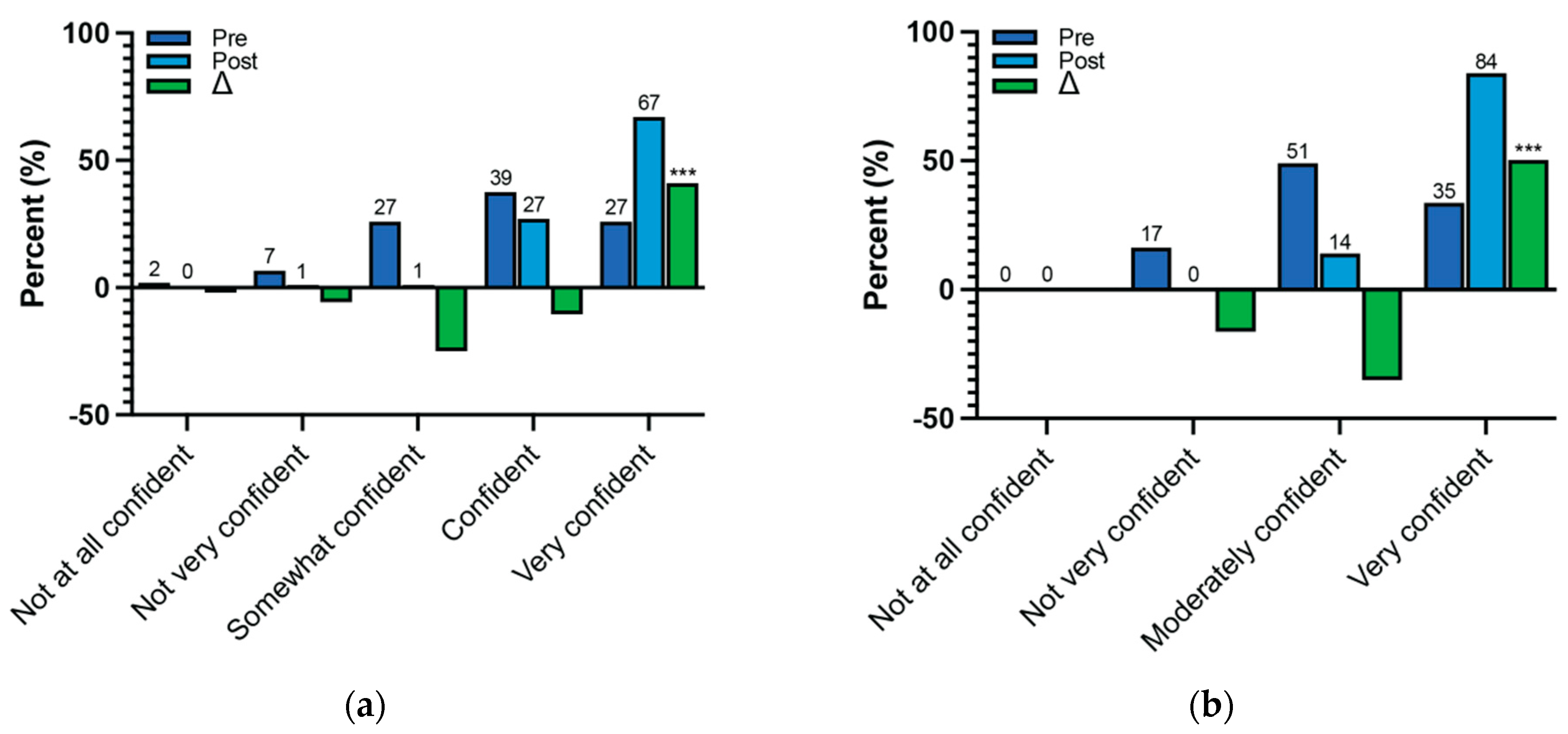

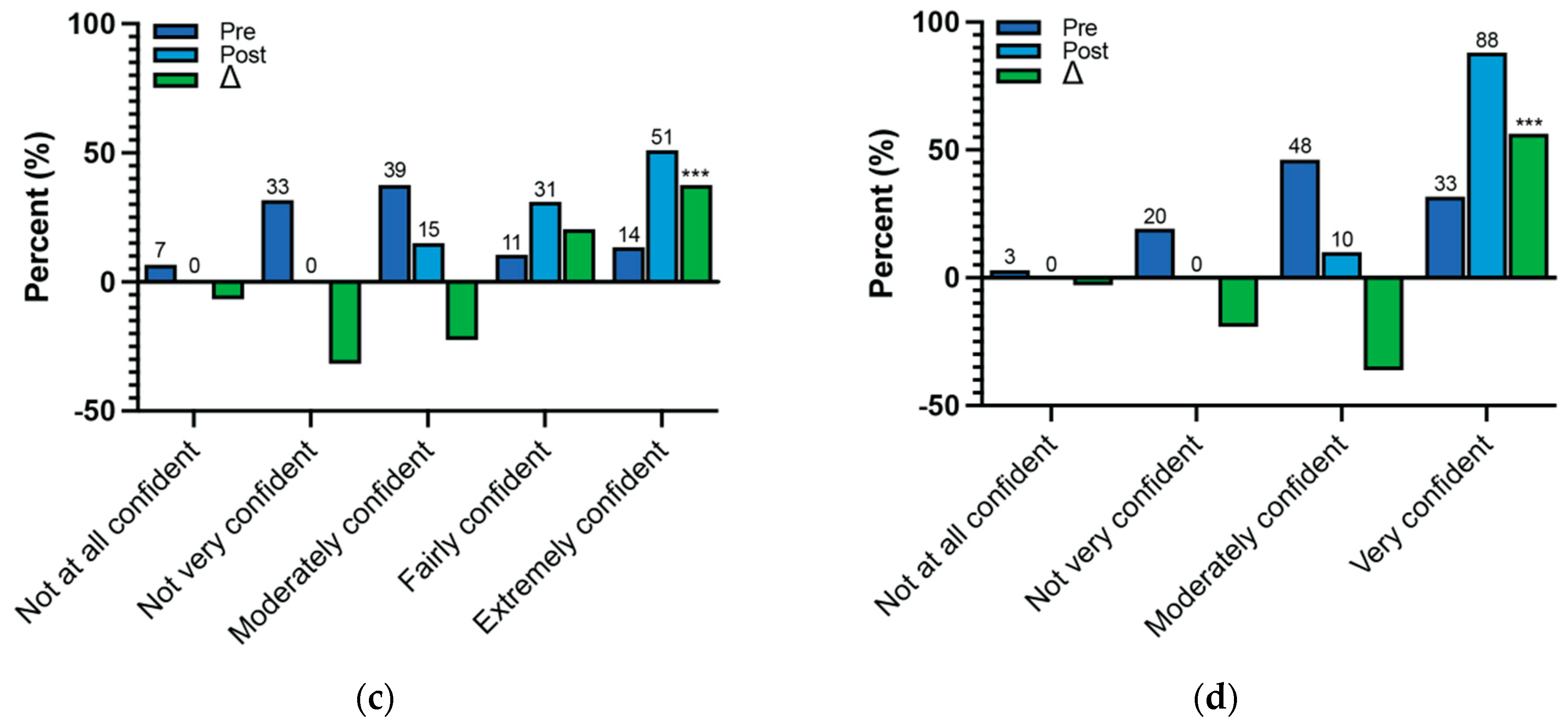

3.4. Communication and Response Skills

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DR | Dominican Republic |

| CWP | Columbia World Project |

| UNIBE | Universidad Iberoamericana |

| CUIMC | Columbia University Irving Medical Center |

| GCCHE | Global Consortium on Climate and Health Education |

Appendix A

| Module 1–2: Climate Change, Human Health, and Community Resilience |

Learning Objectives:

|

| Module 3–4: Climate Change and Extreme Heat |

Learning Objectives:

|

| Module 5: Climate Change and Degraded Air Quality |

Learning Objectives:

|

| Module 6: Vector-borne Disease |

Learning Objectives:

|

| Module 7: Extreme Weather Events |

Learning Objectives:

|

| Module 8: Community Mental Health |

Learning Objectives

|

| Climate Change Awareness | |

| Spanish | English |

| ¿Crees que el cambio climático es real? | Do you believe that climate change is real? |

| ¿Qué tan preocupado estás por el cambio climático? | How concerned are you about climate change? |

| ¿Qué significa “cambio climático” para ti? (Marca todos los que apliquen) | What does “climate change” mean to you? (Check all that apply) |

| ¿Crees que el cambio climático está afectando a tu comunidad? | Do you think climate change is affecting your community? |

| Climate Change Literacy | |

| Spanish | English |

| ¿Qué impactos del cambio climático son relevantes en la República Dominicana? (Marca todos los que apliquen) | What climate change impacts are relevant to the Dominican Republic? (Check all that apply) |

| Si el cambio climático es real, ¿cuándo crees que sucederá? | If climate change is real, when do you think it will happen? |

| Asumiendo que el cambio climático está ocurriendo, ¿qué crees que lo está causando? | Assuming climate change is occurring, what do you think is causing it? |

| ¿Qué tanto crees que el cambio climático afecta a los siguientes? | How much do you think climate change affects the following? |

| ¿Crees que el cambio climático puede afectar la salud humana? | Do you think climate change can affect human health? |

| Si respondiste que si a la pregunta anterior, ¿qué problemas de salud crees que podrían ser influenciados por el cambio climático? (Marca todos los que apliquen) | If you answered yes to the previous question, which health problems do you think could be influenced by climate change? (Check all that apply) |

| ¿Qué tan importante crees que es para los individuos entender cómo el cambio climático afecta la salud? | How important do you think it is for individuals to understand how climate change affects health? |

| Communication and Response Skills | |

| Spanish | English |

| ¿Qué tan confiado estás en que puedes protegerte a ti, a tu familia y a tu comunidad de problemas de salud relacionados con el clima? | How confident are you that you can protect yourself, your family and your community from climate-related health problems? |

| ¿Qué tan confiado te sientes al hablar con otros sobre cómo el cambio climático afecta su salud? | How confident do you feel talking to others about how climate change affects their health? |

| ¿Qué tan confiado te sientes en tu capacidad para identificar a individuos y poblaciones en riesgo de efectos en la salud relacionados con el clima? | How confident do you feel in your ability to identify individuals and populations at risk for climate-related health effects? |

| ¿Qué tan confiado te sientes en tu capacidad para comunicar acciones que los miembros de la comunidad pueden tomar para prevenir los efectos en la salud relacionados con el clima? | How confident do you feel in your ability to communicate actions that community members can take to prevent climate-related health effects? |

References

- Romanello, M.; Walawender, M.; Hsu, S.-C.; Moskeland, A.; Palmeiro-Silva, Y.; Scamman, D.; Ali, Z.; Ameli, N.; Angelova, D.; Ayeb-Karlsson, S.; et al. The 2024 report of the Lancet Countdown on health and climate change: Facing record-breaking threats from delayed action. Lancet 2024, 404, 1847–1896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martyr-Koller, R.; Thomas, A.; Schleussner, C.-F.; Nauels, A.; Lissner, T. Loss and damage implications of sea-level rise on Small Island Developing States. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2021, 50, 245–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vousdoukas, M.I.; Athanasiou, P.; Giardino, A.; Mentaschi, L.; Stocchino, A.; Kopp, R.E.; Menéndez, P.; Beck, M.W.; Ranasinghe, R.; Feyen, L. Small Island Developing States under threat by rising seas even in a 1.5 °C warming world. Nat. Sustain. 2023, 6, 1552–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Development Programme. Dominican Republic NDC Status 2023. Available online: https://climatepromise.undp.org/what-we-do/where-we-work/dominican-republic#:~:text=Key%20highlights%20from%20the%20NDC,only)%20in%20the%20first%20NDC (accessed on 19 November 2024).

- Reyer, C.P.; Adams, S.; Albrecht, T.; Baarsch, F.; Boit, A.; Trujillo, N.C.; Cartsburg, M.; Coumou, D.; Eden, A.; Fernandes, E.; et al. Climate change impacts in Latin America and the Caribbean and their implications for development. Reg. Environ. Chang. 2017, 17, 1601–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Development Programme. Regional Project Will Improve Resilience in Critical Infrastructures in the Dominican Republic, Cuba, and Haiti. 2024. Available online: https://www.undp.org/latin-america/news/regional-project-will-improve-resilience-critical-infrastructures-dominican-republic-cuba-and-haiti (accessed on 19 November 2024).

- United States Agency for International Development (USAID). Building Environmental Resilience with Green Infrastructure Planning in the Dominican Republic; US AID: Washington, DC, USA, 2017.

- World Bank Group. Dominican Republic: Climate and Development Report; World Bank Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, Health and Climate Change: Country Profile 2021: Dominican Republic; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerio de Economia, Planificacion, Y Desarollo. Política Nacional de Cambio Climático (PNCC). 2016. Available online: https://cambioclimatico.gob.do/phocadownload/Documentos/cop25/Politica-de-cambio-climatico-RD.pdf (accessed on 19 November 2024).

- Miguel, I.; Feliz, E.P.; Agramonte, R.; Martinez, P.V.; Vergara, C.; Imbert, Y.; De la Cruz, L.; de Castro, N.; Cedano, O.; De la Paz, Y.; et al. North-south pathways, emerging variants, and high climate suitability characterize the recent spread of dengue virus serotypes 2 and 3 in the Dominican Republic. BMC Infect. Dis. 2024, 24, 751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Columbia World Projects. Construyendo Comunidades Resilientes al Clima en la República Dominicana; Columbia University: New York, NY, USA, 2023; Available online: https://worldprojects.columbia.edu/sites/default/files/2024-01/CWP-DR-ES-web-spread.pdf (accessed on 19 November 2024).

- Global Consortium on Climate and Health Education. Courses. 2024. Available online: https://www.publichealth.columbia.edu/research/programs/global-consortium-climate-health-education/courses (accessed on 19 November 2024).

- Hamilton, W.; Philippe, C.; Hospedales, J.; Dresser, C.; Colebrooke, B.; Hamacher, N.; Humphrey, K.; Sorensen, C. Building capacity of healthcare professionals and community members to address climate and health threats in The Bahamas: Analysis of a green climate fund pilot workshop. Dialogues Health 2023, 3, 100141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorensen, C.; Barboza, C.; Berry, P.; Buss, D.; Campbell, H.; Hadley, K.; Hamacher, N.; Magalhaes, D.; Mantilla, G.; Mendez, A.; et al. Pan American climate resilient health systems: A training course for health professionals. Rev. Panam. Salud. Publica 2024, 48, e83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mocatta, G.; Allen, K.; Beyer, K. Towards a conceptual framework for place-responsive climate-health communication. J. Clim. Chang. Health 2022, 7, 100176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malow, B.A.; Colter, M.; Shortes, C.; Saltwick, S.E.; Morlan, B.W.; Adams, M.S.; Doherty, W.J. Bridging the divide on climate solutions: Development, implementation, and evaluation of an online workshop for climate volunteers. J. Clim. Chang. Health 2022, 7, 100177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duhaime, A.-C.; Futernick, M.; Alexander, M.; Erny, B.C.; Etzel, R.A.; Gordon, I.O.; Guinto, R.; Hertelendy, A.J.; Howard, C.; Maki, L.; et al. Healthcare professionals need to be CCLEAR: Climate collaborators, leaders, educators, advocates, and researchers. J. Clim. Chang. Health 2021, 4, 100078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floss, M.; Ilgenfritz, C.A.V.; Rodrigues, Y.E.; Dilda, A.C.; Corrêa, A.P.B.; de Melo, D.A.C.; Barros, E.F.; Guzmán, C.A.F.; Devlin, E.; Saldiva, P.H.N.; et al. Development and Assessment of a Brazilian Pilot Massive Open Online Course in Planetary Health Education: An Innovative Model for Primary Care Professionals and Community Training. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 663783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorensen, C.; Hamacher, N.; Campbell, H.; Henry, P.; Peart, K.; De Freitas, L.; Hospedales, J. Climate and health capacity building for health professionals in the Caribbean: A pilot course. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1077306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Session 1 (n = 21) | Session 2 (n = 38) | Session 3 (n = 41) | Total (n = 100) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years)—No. (%) | ||||

| 15–17 | 0 (0) | 5 (13) | 5 (12) | 10 (10) |

| 18–24 | 2 (10) | 11 (29) | 11 (27) | 24 (24) |

| 25–35 | 4 (19) | 7 (18) | 10 (24) | 21 (21) |

| 35+ | 15 (71) | 15 (40) | 15 (37) | 45 (45) |

| Female (sex)—No. (%) | 12 (57) | 23 (61) | 35 (85) | 70 (70) |

| Neighborhood (Cristo Rey)—No. (%) | ||||

| Since before 1 year old | 1 (5) | 1 (3) | 1 (2) | 3 (3) |

| Since 1–5 years old | 0 (0.0) | 4 (10) | 2 (5) | 6 (6) |

| Since 6–10 years old | 1 (5) | 1 (3) | 6 (15) | 8 (8) |

| Since 11–20 years old | 2 (9) | 3 (8) | 0 (0) | 5 (5) |

| Since >20 years old | 11 (52) | 15 (39) | 1 (2) | 27 (27) |

| I don’t live in Cristo Rey | 6 (29) | 14 (37) | 31 (76) | 51 (51) |

| Climate Change Awareness | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Do you believe that climate change is real?—No. (%) | ||||

| Response | Pre-Course Survey (n = 104) | Post-Course Survey (n = 100) | Percent Δ (%) | p-value |

| Yes | 103 (99) | 100 (100) | 1 | 0.445 |

| No | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | |

| I don’t know | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | −1 | |

| How concerned are you about climate change?—No. (%) | ||||

| Response | Pre-course survey (n = 104) | Post-course survey (n = 100) | Percent Δ (%) | p-value |

| Very concerned | 75 (72) | 88 (88) | 13 | 0.264 |

| Somewhat concerned | 26 (25) | 10 (10) | −16 | |

| Not concerned | 1 (1) | 2 (2) | 1 | |

| I don’t know, not sure | 2 (2) | 0 (0) | −2 | |

| Do you think climate change is affecting your community?—No. (%) | ||||

| Response | Pre-course survey (n = 104) | Post-course survey (n = 100) | Percent Δ (%) | p-value |

| Yes | 100 (96) | 96 (96) | 0 | 0.451 |

| No | 3 (3) | 2 (2) | −1 | |

| I don’t know | 1 (1) | 2 (2) | 1 | |

| What does “climate change” mean to you? (Check all that apply)—No. (%) | ||||

| Response | Pre-course survey (n = 104) | Post-course survey (n = 100) | Percent Δ (%) | p-value |

| Changes in weather patterns/conditions (e.g., more rainfall, more droughts) | 78 (75) | 80 (80) | 5 | 0.408 |

| Changes in sea level | 52 (50) | 58 (58) | 8 | 0.264 |

| Changes in temperature | 79 (76) | 81 (81) | 5 | 0.400 |

| Changes in the environment | 72 (69) | 78 (78) | 9 | 0.204 |

| Extreme heat | 62 (60) | 77 (77) | 17 | 0.010 |

| Global warming | 76 (73) | 77 (77) | 1 | 0.628 |

| Climate change literacy | ||||

| What climate change impacts are relevant to the Dominican Republic? (Check all that apply)—No. (%) | ||||

| Response | Pre-course survey (n = 104) | Post-course survey (n = 100) | Percent Δ (%) | p-value |

| More flooding | 95 (91) | 93 (93) | 2 | 0.796 |

| Stronger hurricanes | 66 (63) | 81 (81) | 18 | 0.008 |

| More droughts | 55 (53) | 70 (70) | 17 | 0.015 |

| Higher temperatures | 84 (81) | 90 (90) | 9 | 1.000 |

| Colder winters | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | 1.000 |

| Rising sea levels | 44 (42) | 69 (69) | 27 | <0.001 |

| More forest fires | 60 (58) | 55 (55) | −3 | 0.778 |

| Poorer air quality | 67 (64) | 80 (80) | 16 | 0.019 |

| Extinction of animal/plant species/loss of biodiversity | 51 (49) | 54 (54) | 5 | 0.487 |

| Melting glaciers | 16 (15) | 24 (24) | 9 | 0.158 |

| If climate change is real, when do you think it will happen?—No. (%) | ||||

| Response | Pre-course survey (n = 101) | Post-course survey (n = 98) | Percent Δ (%) | p-value |

| Happening now | 95 (94) | 96 (98) | 4 | 0.462 |

| In the future | 6 (6) | 2 (2) | −4 | |

| I don’t know | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | |

| Assuming climate change is occurring, what do you think is causing it?—No. (%) | ||||

| Response | Pre-course survey (n = 104) | Post-course survey (n = 100) | Percent Δ (%) | p-value |

| Totally due to human activities | 28 (27) | 33 (33) | 6 | 0.977 |

| Mainly by human activities | 25 (24) | 21 (21) | −3 | |

| Due to both human activities and natural environmental changes | 40 (38) | 37 (37) | −1 | |

| Mainly due to natural environmental changes | 4 (4) | 6 (6) | 2 | |

| Totally due to natural environmental changes | 7 (7) | 3 (3) | −4 | |

| None of the above because climate change is not happening | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | |

| How much do you think climate change affects the following? —No. (%) | ||||

| Response | Pre-course survey (n = 102) | Post-course survey (n = 98) | Percent Δ (%) | p-value |

| You personally | ||||

| None | 1 (1) | 2 (2) | 1 | 0.808 |

| A little | 8 (8) | 6 (6) | −2 | |

| Moderately | 37 (36) | 36 (37) | 1 | |

| A lot | 56 (55) | 53 (54) | −1 | |

| I don’t know | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 1 | |

| Response | Pre-course survey (n = 100) | Post-course survey (n = 95) | Percent Δ (%) | p-value |

| People in your community | ||||

| None | 0 (0) | 3 (3) | 3 | 0.105 |

| A little | 4 (4) | 0 (0) | −4 | |

| Moderately | 22 (22) | 13 (14) | −8 | |

| A lot | 69 (69) | 76 (80) | 11 | |

| I don’t know | 5 (5) | 3 (3) | −2 | |

| Response | Pre-course survey (n = 101) | Post-course survey (n = 93) | Percent Δ (%) | p-value |

| People in your country | ||||

| None | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 1 | 0.345 |

| A little | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 1 | |

| Moderately | 12 (12) | 4 (4) | −8 | |

| A lot | 87 (86) | 86 (93) | 7 | |

| I don’t know | 2 (2) | 1 (1) | −1 | |

| Response | Pre-course survey (n = 98) | Post-course survey (n = 93) | Percent Δ (%) | p-value |

| People in other countries | ||||

| None | 1 (1) | 3 (3) | 2 | 0.231 |

| A little | 2 (2) | 1 (1) | −1 | |

| Moderately | 8 (8) | 10 (11) | 3 | |

| A lot | 81 (83) | 70 (75) | −8 | |

| I don’t know | 6 (6) | 9 (10) | 4 | |

| Response | Pre-course survey (n = 96) | Post-course survey (n = 89) | Percent Δ (%) | p-value |

| Future generations | ||||

| None | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 1 | 0.132 |

| A little | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 | |

| Moderately | 7 (7) | 0 (0) | −7 | |

| A lot | 75 (78) | 74 (83) | 5 | |

| I don’t know | 13 (14) | 13 (15) | 1 | |

| Do you think climate change can affect human health?—No. (%) | ||||

| Response | Pre-course survey (n = 104) | Post-course survey (n = 95) | Percent Δ (%) | p-value |

| Yes | 104 (100) | 95 (100) | 0 | 1.000 |

| No | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | |

| I don’t know, I’m not sure | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | |

| How important do you think it is for individuals to understand how climate change affects health?—No. (%) | ||||

| Response | Pre-course survey (n = 104) | Post-course survey (n = 95) | Percent Δ (%) | p-value |

| Very important—It is very important for everyone to understand the health risks posed by climate change so that they can take the necessary precautions and protect themselves. | 94 (90) | 89 (94) | 4 | 0.364 |

| Important—Being aware of how climate change impacts health helps people make informed decisions about their well-being and that of their communities. | 9 (9) | 5 (5) | −4 | |

| Neutral—While it is beneficial for people to know about the health impacts of climate change, there may be other more pressing concerns. | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 1 | |

| Not very important—While awareness of the health impacts of climate change is helpful, it may not be a priority for everyone. | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | −1 | |

| Not important—People do not need to understand how climate change affects health because the impacts are minimal. | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Weinstein, H.N.W.; Hadley, K.; Patel, J.; Silliman, S.; Gomez Carrasco, R.Y.; Arredondo Santana, A.J.; Sosa, H.; Rosa, S.M.; Martinez, C.; Hamacher, N.P.; et al. A Train-the-Trainer Approach to Build Community Resilience to the Health Impacts of Climate Change in the Dominican Republic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 650. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22040650

Weinstein HNW, Hadley K, Patel J, Silliman S, Gomez Carrasco RY, Arredondo Santana AJ, Sosa H, Rosa SM, Martinez C, Hamacher NP, et al. A Train-the-Trainer Approach to Build Community Resilience to the Health Impacts of Climate Change in the Dominican Republic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(4):650. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22040650

Chicago/Turabian StyleWeinstein, Hannah N. W., Kristie Hadley, Jessica Patel, Sarah Silliman, R. Yamir Gomez Carrasco, Andres J. Arredondo Santana, Heidi Sosa, Stephanie M. Rosa, Carol Martinez, Nicola P. Hamacher, and et al. 2025. "A Train-the-Trainer Approach to Build Community Resilience to the Health Impacts of Climate Change in the Dominican Republic" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 4: 650. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22040650

APA StyleWeinstein, H. N. W., Hadley, K., Patel, J., Silliman, S., Gomez Carrasco, R. Y., Arredondo Santana, A. J., Sosa, H., Rosa, S. M., Martinez, C., Hamacher, N. P., Campbell, H., Sullivan, J. K., Magalhães, D. d. P., Sorensen, C., & Valenzuela González, A. C. (2025). A Train-the-Trainer Approach to Build Community Resilience to the Health Impacts of Climate Change in the Dominican Republic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(4), 650. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22040650