Hearing Loss and Social Isolation in Community-Dwelling Older Adults: The Role of Neighborhood Disorder and Perceived Social Cohesion

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data and Sample

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Social Isolation

2.2.2. Hearing Loss

2.2.3. Neighborhood Disorder

2.2.4. Perceived Social Cohesion

2.2.5. Covariates

2.3. Data Analyses

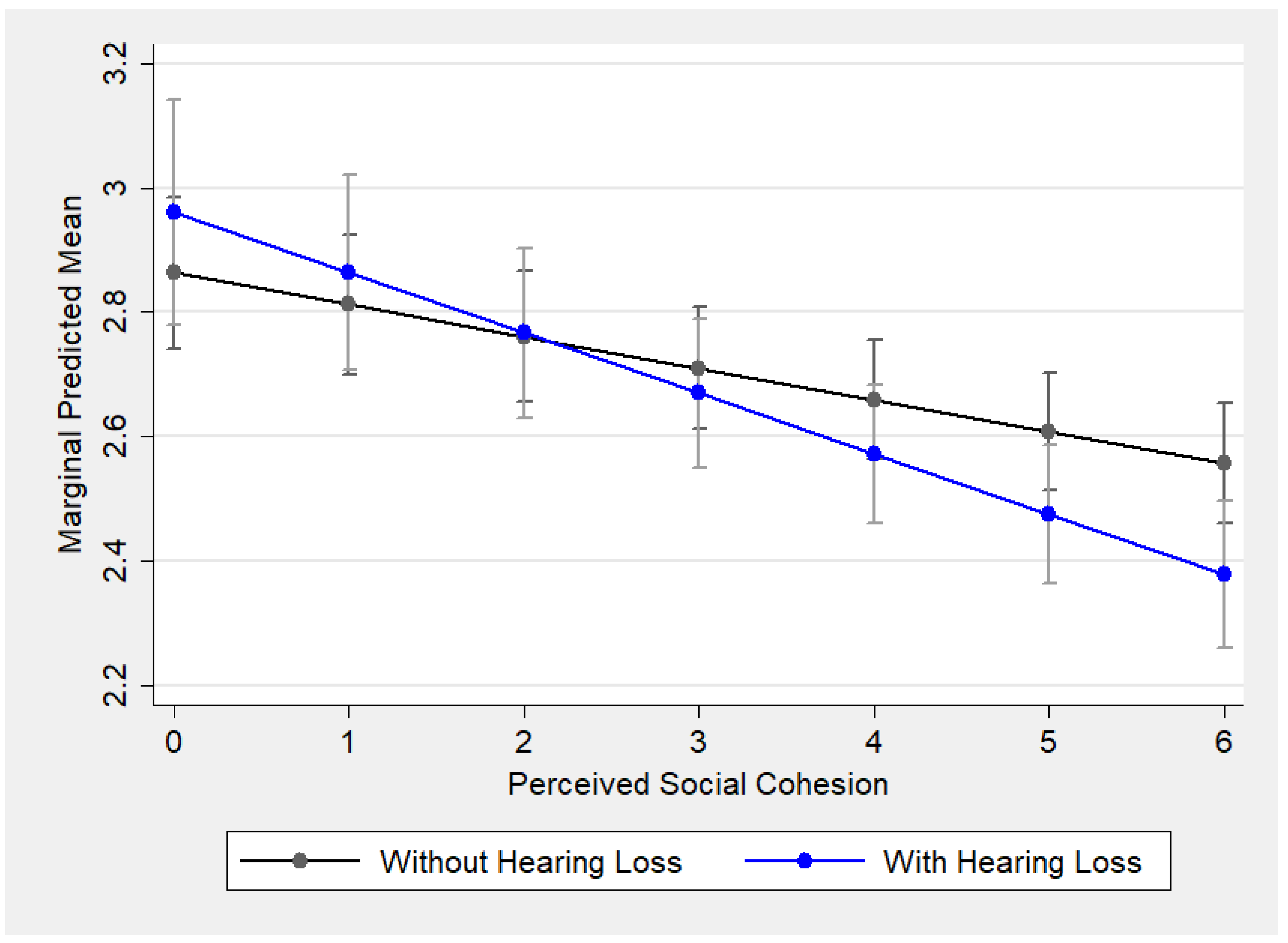

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Huang, Q.; Tang, J. Age-related hearing loss or presbycusis. Eur. Arch. Oto-Rhino-Laryngol. 2010, 267, 1179–1191. [Google Scholar]

- Quaranta, A.; Assennato, G.; Sallustio, V. Epidemiology of hearing problems among adults in Italy. Scand. Audiol. Suppl. 1996, 42, 9–13. [Google Scholar]

- Quaranta, N.; Coppola, F.; Casulli, M.; Barulli, M.R.; Panza, F.; Tortelli, R.; Solfrizzi, V.; Sabbà, C.; Logroscino, G. Epidemiology of age related hearing loss: A review. Hear. Balance Commun. 2015, 13, 77–81. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman, H.J.; Dobie, R.A.; Losonczy, K.G.; Themann, C.L.; Flamme, G.A. Declining prevalence of hearing loss in US adults aged 20 to 69 years. JAMA Otolaryngol.–Head Neck Surg. 2017, 143, 274–285. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Administration for Community Living 2023. Profile of Older Americans; Administration for Community Living: Washington, DC, USA, 2024.

- National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders. Quick Statistics About Hearing. 2016. Available online: https://www.nidcd.nih.gov/health/statistics/quick-statistics-hearing#6 (accessed on 31 March 2025).

- Arlinger, S. Negative consequences of uncorrected hearing loss-a review. Int. J. Audiol. 2003, 42, 2S17–2S20. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ciorba, A.; Bianchini, C.; Pelucchi, S.; Pastore, A. The impact of hearing loss on the quality of life of elderly adults. Clin. Interv. Aging 2012, 7, 159–163. [Google Scholar]

- Dalton, D.S.; Cruickshanks, K.J.; Klein, B.E.; Klein, R.; Wiley, T.L.; Nondahl, D.M. The impact of hearing loss on quality of life in older adults. Gerontologist 2003, 43, 661–668. [Google Scholar]

- The U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory on the Healing Effects of Social Connection and Community. Our Epidemic of Loneliness and Isolation; Office of the U.S. Surgeon General: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, S.; Sheik Ali, S.; Ahmed, W. A review of the impact of hearing interventions on social isolation and loneliness in older people with hearing loss. Eur. Arch. Oto-Rhino-Laryngol. 2021, 278, 4653–4661. [Google Scholar]

- Shukla, A.; Harper, M.; Pedersen, E.; Goman, A.; Suen, J.J.; Price, C.; Applebaum, J.; Hoyer, M.; Lin, F.R.; Reed, N.S. Hearing loss, loneliness, and social isolation: A systematic review. Otolaryngol.–Head Neck Surg. 2020, 162, 622–633. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, A.R.; Cudjoe, T.K.; Rebok, G.W.; Swenor, B.K.; Deal, J.A. Hearing and vision impairment and social isolation over 8 years in community-dwelling older adults. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 779. [Google Scholar]

- Sugiyama, M.; Chau, H.-W.; Abe, T.; Kato, Y.; Jamei, E.; Veeroja, P.; Mori, K.; Sugiyama, T. Third places for older adults’ social engagement: A scoping review and research agenda. Gerontologist 2023, 63, 1149–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Latham, K.; Clarke, P.J. Neighborhood Disorder, Perceived Social Cohesion, and Social Participation Among Older Americans: Findings From the National Health and Aging Trends Study. J. Aging Health 2018, 30, 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prieur Chaintré, A.; Couturier, Y.; Nguyen, T.T.; Levasseur, M. Influence of hearing loss on social participation in older adults: Results from a scoping review. Res. Aging 2024, 46, 72–90. [Google Scholar]

- Lawton, M.P.; Nahemow, L. Ecology and the aging process. In Psychology of Adult Development and Aging; Eisdorfer, C., Lawton, M.P., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 1973; pp. 619–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwarsson, S. A long-term perspective on person–environment fit and ADL dependence among older Swedish adults. Gerontologist 2005, 45, 327–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Smith, J.; Dunkle, R.E.; Ingersoll-Dayton, B.; Antonucci, T.C. Health and Social–Physical Environment Profiles Among Older Adults Living Alone: Associations with depressive symptoms. J. Gerontol. Ser. B 2017, 74, 675–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahl, H.W.; Iwarsson, S.; Oswald, F. Aging well and the environment: Toward an integrative model and research agenda for the future. Gerontologist 2012, 52, 306–316. [Google Scholar]

- Freedman, V.A.; Schrack, J.A.; Skehan, M.E. National Health and Aging Trends Study User Guide: Rounds 1–13 Final Release; Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Kasper, J.D.; Freedman, V.A. Findings From the 1st Round of the National Health and Aging Trends Study (NHATS): Introduction to a Special Issue. J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2014, 69, S1–S7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pohl, J.S.; Cochrane, B.B.; Schepp, K.G.; Woods, N.F. Measuring social isolation in the national health and aging trends study. Res. Gerontol. Nurs. 2017, 10, 277–287. [Google Scholar]

- Berkman, L.F. Social Networks, Host Resistance, and Mortality: A Follow-Up Study of Alameda County Residents. Doctoral Dissertation, Retrieved from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. University of California, Berkeley, CA, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Berkman, L.F.; Syme, S.L. Social Networks, Host Resistance, and Mortality: A Nine-Year Follow-up Study of Alameda County Residents. In Psychosocial Processes and Health; Steptoe, A., Wardle, J., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1994; pp. 43–67. ISBN 978-0-521-42618-3. [Google Scholar]

- Kuo, P.L.; Huang, A.R.; Ehrlich, J.R.; Kasper, J.; Lin, F.R.; McKee, M.M.; Reed, N.S.; Swenor, B.K.; Deal, J.A. Prevalence of concurrent functional vision and hearing impairment and association with dementia in community-dwelling Medicare beneficiaries. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e211558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cagney, K.A.; Glass, T.A.; Skarupski, K.A.; Barnes, L.L.; Schwartz, B.S.; Mendes de Leon, C.F. Neighborhood-level cohesion and disorder: Measurement and validation in two older adult urban populations. J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2009, 64B, 415–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampson, R.J.; Raudenbush, S.W.; Earls, F. Neighborhoods and violent crime: A multilevel study of collective efficacy. Science 1997, 277, 918–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bessen, S.; Zhang, W.; Morales, E.E.G.; Akré, E.R.L.; Reed, N.S. Hearing Aid Use at the Intersection of Race, Ethnicity, and Socioeconomic Status. JAMA Health Forum 2024, 5, e243854, American Medical Association: Chicago, IL, USA. [Google Scholar]

- You, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wei, M.; Tang, M.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Cao, Q. Mediation Role of Recreational Physical Activity in the Relationship between the Dietary Intake of Live Microbes and the Systemic Immune-Inflammation Index: A Real-World Cross-Sectional Study. Nutrients 2024, 16, 777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montaquila, J.; Freedman, V.A.; Edwards, B.; Kasper, J.D. National Health and Aging Trends Study Round 1 Sample Design and Selection. NHATS Technical Paper #1; Johns Hopkins University School of Public Health: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Montaquila, J.; Freedman, V.A.; Spillman, B.; Kasper, J.D. National Health and Aging Trends Study Development of Round 1 Survey Weights. NHATS Technical Paper #2; Johns Hopkins University School of Public Health: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Montaquila, J.; Freedman, V.A.; Spillman, B.; Kasper, J.D. National Health and Aging Trends Study Development of Round 1 Survey Weights. NHATS Technical Paper #6; Johns Hopkins University School of Public Health: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Montaquila, J.; Freedman, V.A.; Spillman, B.; Kasper, J.D. National Health and Aging Trends Study Development of Round 3 Survey Weights. NHATS Technical Paper #9; Johns Hopkins University School of Public Health: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Stata, 13.0; StataCorp: College Station, TX, USA, 2013.

- Heine, C.; Browning, C.J. Communication and psychosocial consequences of sensory loss in older adults: Overview and rehabilitation directions. Disabil. Rehabil. 2002, 24, 763–773. [Google Scholar]

- Mick, P.; Kawachi, I.; Lin, F.R. The association between hearing loss and social isolation in older adults. Otolaryngol.–Head Neck Surg. 2014, 150, 378–384. [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein, B.E.; Ventry, I.M. Hearing impairment and social isolation in the elderly. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 1982, 25, 593–599. [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein, B.E.; Sirow, L.W.; Moser, S. Relating hearing aid use to social and emotional loneliness in older adults. Am. J. Audiol. 2016, 25, 54–61. [Google Scholar]

- Dawes, P.; Emsley, R.; Cruickshanks, K.J.; Moore, D.R.; Fortnum, H.; Edmondson-Jones, M.; McCormack, A.; Munro, K.J. Hearing loss and cognition: The role of hearing AIDS, social isolation and depression. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0119616. [Google Scholar]

- Strawbridge, W.J.; Wallhagen, M.I.; Shema, S.J.; Kaplan, G.A. Negative consequences of hearing impairment in old age: A longitudinal analysis. Gerontologist 2000, 40, 320–326. [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein, B.E. Outcome measures in the hearing aid fitting/selection process. Trends Amplif. 1997, 2, 117–137. [Google Scholar]

- Donahue, A.; Dubno, J.R.; Beck, L. Accessible and affordable hearing health care for adults with mild to moderate hearing loss. Ear Hear. 2010, 31, 2–6. [Google Scholar]

- Fowler, E.; Woodside, J.V.; Kee, F.; Loughrey, D.; Lawlor, B.; Power, J.M. Reconnecting to others: Grounded theory of social functioning following age-related hearing loss. Ageing Soc. 2022, 42, 2008–2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, E.S.L.; Zhang, Z. Moderating Role of Neighborhood Environment in the Associations Between Hearing Loss and Cognitive Challenges Among Older Adults: Evidence From US National Study. Res. Aging 2024, 46, 400–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bainbridge, K.E.; Ramachandran, V. Hearing Aid Use Among Older U.S. Adults: The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2005–2006 and 2009–2010. Ear Hear. 2014, 35, 289–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, D.S.; Wu, M.M.; Nothelle, S.; Smith, J.M.; Gleason, K.; Oh, E.S.; Lum, H.D.; Reed, N.S.; Wolff, J.L. The Medicare annual wellness visit: An opportunity to improve health system identification of hearing loss? J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2024, 72, 3089–3097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, M.L.; Sixsmith, J.; Hamilton-Pryde, A.; Rogowsky, R.; Scrutton, P.; Pengelly, R.; Woolrych, R.; Creaney, R. Co-creating inclusive spaces and places: Towards an intergenerational and age-friendly living ecosystem. Front. Public Health 2023, 10, 996520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDaid, D.; Park, A.L. Addressing loneliness in older people through a personalized support and community response program. J. Aging Soc. Policy 2024, 36, 1062–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinella, L.; Bosco, A.; Traficante, S.; Napoletano, R.; Ricciardi, E.; Spano, G.; Lopez, A.; Sanesi, G.; Bergantino, A.S.; Caffò, A.O. Fostering an age-friendly sustainable transport system: A psychological perspective. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crews, J.E.; Campbell, V.A. Vision impairment and hearing loss among community-dwelling older Americans: Implications for health and functioning. Am. J. Public Health 2004, 94, 823–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, J.; Gopinath, B.; Karpa, M.J.; McMahon, C.M.; Rochtchina, E.; Leeder, S.R.; Mitchell, P. Hearing loss impacts on the use of community and informal supports. Age Ageing 2010, 39, 458–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Total Analytic Sample | With Hearing Loss | Without Hearing Loss | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | M (SD)/% | N * | M (SD)/% | N * | M (SD)/% | N * |

| Age category, % | ||||||

| 65–69 years old | 21.97 | 868 | 7.43 | 37 | 24.07 | 831 |

| 70–74 years old | 23.67 | 935 | 15.46 | 77 | 24.86 | 858 |

| 75–79 years old | 21.24 | 839 | 21.29 | 106 | 21.23 | 733 |

| 80–84 years old | 19.34 | 764 | 25.1 | 125 | 18.51 | 639 |

| 85–89 years old | 9.65 | 381 | 20.68 | 103 | 8.05 | 278 |

| 90+ years old | 4.13 | 163 | 10.04 | 50 | 3.27 | 113 |

| Female, % | 58.18 | 2298 | 42.77 | 213 | 60.4 | 2085 |

| Education level, % | ||||||

| Less than HS | 22.76 | 899 | 19.88 | 99 | 23.17 | 800 |

| HS graduate | 49.67 | 1962 | 52.61 | 262 | 49.25 | 1700 |

| Some college + | 27.57 | 1089 | 27.51 | 137 | 27.58 | 952 |

| Race/ethnicity, % | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 73.9 | 2919 | 88.55 | 441 | 71.78 | 2478 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 20.94 | 827 | 8.03 | 40 | 22.8 | 787 |

| Hispanic | 5.16 | 204 | 3.41 | 17 | 5.42 | 187 |

| Living alone, % | 32.13 | 1269 | 32.93 | 164 | 32.01 | 1105 |

| Medicaid receipt, % | 11.96 | 468 | 8.08 | 40 | 12.53 | 428 |

| Annual total income | $29,901.34 (2.84) | 3950 | $34,452 (2.24) | 498 | $29,313 (2.92) | 3452 |

| Self-rated health | 2.32 (1.08) | 3949 | 2.38 (0.99) | 498 | 2.31 (1.09) | 3451 |

| Chronic diseases | 2.47 (1.51) | 3922 | 2.53 (1.49) | 495 | 2.46 (1.52) | 3427 |

| Neighborhood disorder | 0.28 (0.91) | 3948 | 0.14 (0.52) | 498 | 0.3 (0.95) | 3450 |

| Perceived social cohesion | 4.27 (1.64) | 3773 | 4.54 (1.56) | 476 | 4.23 (1.65) | 3297 |

| Social isolation | 2.41 (1.19) | 3934 | 2.26 (1.15) | 496 | 2.43 (1.2) | 3438 |

| Outcome: Social Isolation | Unconditional Null Model | Main Effect (Model 1) | With Covariates (Model 2) | With Interactions Terms (Model 3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 2.3 *** | 2.53 *** | 4.34 *** | 4.32 *** |

| Time | 0.01 | 0.01 | −0.01 | −0.004 |

| Hearing loss | −0.05 | −0.1 ** | 0.1 | |

| Neighborhood disorder | 0.06 *** | 0.05 ** | 0.05 ** | |

| Social cohesion | −0.06 *** | −0.06 *** | −0.05 *** | |

| Age | 0.08 ** | 0.09 ** | ||

| Sex (ref: male) | −0.21 *** | −0.21 *** | ||

| Education level | −0.11 *** | −0.12 *** | ||

| Race/ethnicity (ref: White) | ||||

| Black | 0.14 *** | 0.14 *** | ||

| Hispanic | 0.24 ** | 0.24 ** | ||

| Medicaid receipt | 0.13 *** | 0.13 *** | ||

| Annual total income | −0.15 *** | −0.15 *** | ||

| Self-rated health | −0.08 *** | −0.08 *** | ||

| Chronic diseases | 0.002 | 0.002 | ||

| Living alone | 0.49 *** | 0.49 *** | ||

| ND * ARHL | −0.019 | |||

| PSC * ARHL | −0.05 * | |||

| Variance components | ||||

| Level 1 variance | 0.34 | 0.34 | 0.34 | 0.34 |

| Level 2 variance | 1.05 | 0.99 | 0.73 | 0.73 |

| ICC | 0.75 | 0.74 | 0.68 | 0.68 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Baik, S.; Kim, K. Hearing Loss and Social Isolation in Community-Dwelling Older Adults: The Role of Neighborhood Disorder and Perceived Social Cohesion. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 583. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22040583

Baik S, Kim K. Hearing Loss and Social Isolation in Community-Dwelling Older Adults: The Role of Neighborhood Disorder and Perceived Social Cohesion. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(4):583. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22040583

Chicago/Turabian StyleBaik, Sol, and Kyeongmo Kim. 2025. "Hearing Loss and Social Isolation in Community-Dwelling Older Adults: The Role of Neighborhood Disorder and Perceived Social Cohesion" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 4: 583. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22040583

APA StyleBaik, S., & Kim, K. (2025). Hearing Loss and Social Isolation in Community-Dwelling Older Adults: The Role of Neighborhood Disorder and Perceived Social Cohesion. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(4), 583. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22040583