Pathway from Exposure to an E-Cigarette Prevention Social Media Campaign to Increased Quitting Intentions: A Randomized Trial Among Young Adult E-Cigarette Users

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Measures

2.3. Statistical Analysis

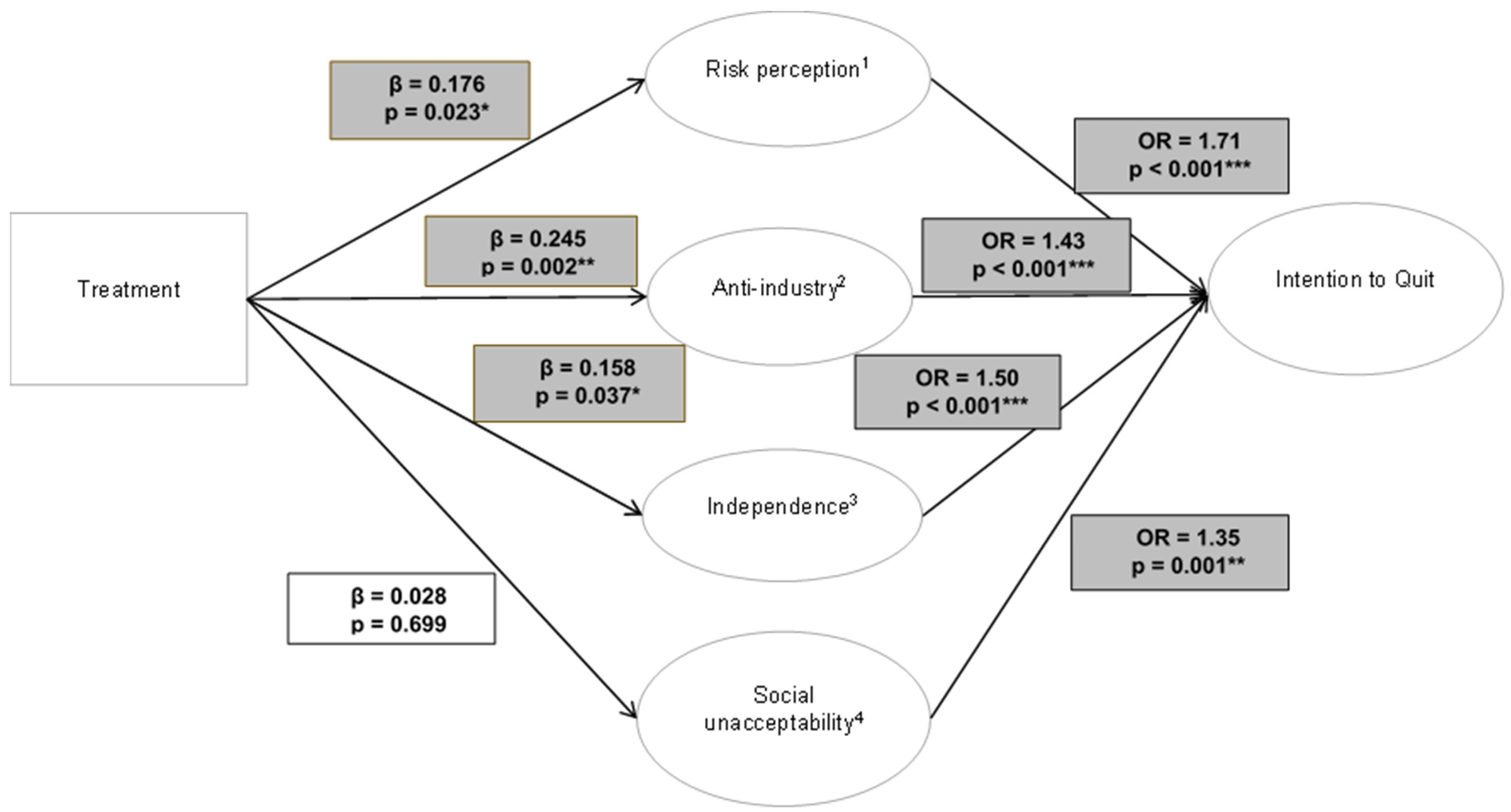

3. Results

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cornelius, M.E.; Loretan, C.G.; Jamal, A.; Davis Lynn, B.C.; Mayer, M.; Alcantara, I.C.; Neff, L. Tobacco Product Use Among Adults—United States, 2021. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2023, 72, 475–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patrick, M.E.; Johnston, L.D.; O’Malley, P.M.; Miech, R.A. Monitoring the Future Panel Study Annual Report: National Data on Substance Use Among Adults Ages 19 to 60, 1976–2022; Monitoring the Future Monograph Series; Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2023; Available online: https://monitoringthefuture.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/mtfpanel2023.pdf (accessed on 18 November 2024).

- Benowitz, N.L. Nicotine Addiction. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 362, 2295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goriounova, N.A.; Mansvelder, H.D. Short- and Long-Term Consequences of Nicotine Exposure during Adolescence for Prefrontal Cortex Neuronal Network Function. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2012, 2, a012120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, T.D.; Arnold, M.K.; Ro, V.; Martin, L.; Rice, T.R. Systematic Review of Electronic Cigarette Use (Vaping) and Mental Health Comorbidity Among Adolescents and Young Adults. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2021, 23, 415–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brett, E.I.; Miller, M.B.; Leavens, E.L.S.; Lopez, S.V.; Wagener, T.L.; Leffingwell, T.R. Electronic cigarette use and sleep health in young adults. J. Sleep Res. 2020, 29, e12902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lechner, W.V.; Janssen, T.; Kahler, C.W.; Audrain-McGovern, J.; Leventhal, A.M. Bi-directional associations of electronic and combustible cigarette use onset patterns with depressive symptoms in adolescents. Prev. Med. 2017, 96, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, C.; Xie, Z.; Li, D. Association of electronic cigarette use with self-reported difficulty concentrating, remembering, or making decisions in US youth. Tob. Induc. Dis. 2020, 18, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.; Ossip, D.J.; Rahman, I.; O’Connor, R.J.; Li, D. Electronic cigarette use and subjective cognitive complaints in adults. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0241599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatta, D.N.; Glantz, S.A. Association of E-Cigarette Use With Respiratory Disease Among Adults: A Longitudinal Analysis. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2020, 58, 182–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wills, T.A.; Soneji, S.S.; Choi, K.; Jaspers, I.; Tam, E.K. E-cigarette use and respiratory disorders: An integrative review of converging evidence from epidemiological and laboratory studies. Eur. Respir. J. 2021, 57, 1901815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agaku, I.T.; Perks, S.N.; Odani, S.; Glover-Kudon, R. Associations between public e-cigarette use and tobacco-related social norms among youth. Tob. Control 2020, 29, 332–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duong, H.T.; Liu, J. Vaping in the News: The Influence of News Exposure on Perceived e-Cigarette Use Norms. Am. J. Health Educ. 2019, 50, 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, C.N.; Noar, S.M.; Rogers, B.D. The Persuasive Power of Oral Health Promotion Messages: A Theory of Planned Behavior Approach to Dental Checkups Among Young Adults. Health Commun. 2013, 28, 304–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namkoong, K.; Nah, S.; Record, R.A.; Van Stee, S.K. Communication, Reasoning, and Planned Behaviors: Unveiling the Effect of Interactive Communication in an Anti-Smoking Social Media Campaign. Health Commun. 2017, 32, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paek, H.-J.; Oh, H.J.; Hove, T. How Media Campaigns Influence Children’s Physical Activity: Expanding the Normative Mechanisms of the Theory of Planned Behavior. J. Health Commun. 2012, 17, 869–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, E.C.; Kreslake, J.M.; Tulsiani, S.; Liu, M.S.; Vallone, D.M. Pathways to prevent e-cigarette use: Examining the effectiveness of the truth antivaping campaign. Health Psychol. Off. J. Div. Health Psychol. Am. Psychol. Assoc. 2024, 43, 418–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, E.C.; Kreslake, J.M.; Tulsiani, S.; McKay, T.; Vallone, D. Reducing e-cigarette use among youth and young adults: Evidence of the truth campaign’s impact. Tob. Control 2023, 34, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, E.C.; Niederdeppe, J.; Rath, J.M.; Bennett, M.; Romberg, A.; Pitzer, L.; Xiao, H.; Vallone, D.M. Using Aggregate Temporal Variation in Ad Awareness to Assess the Effects of the truth® Campaign on Youth and Young Adult Smoking Behavior. J. Health Commun. 2020, 25, 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreslake, J.M.; Aarvig, K.; Liu, M.S.; Vallone, D.M.; Hair, E.C. Pathways to quitting e-cigarettes among youth and young adults: Evidence from the truth® campaign. Am. J. Health Promot. 2023, 38, 930–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anker, A.E.; Feeley, T.H.; McCracken, B.; Lagoe, C.A. Measuring the Effectiveness of Mass-Mediated Health Campaigns Through Meta-Analysis. J. Health Commun. 2016, 21, 439–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, W.D.; Abroms, L.C.; Broniatowski, D.; Napolitano, M.; Arnold, J.; Ichimiya, M.; Agha, S. Digital Media for Behavior Change: Review of an Emerging Field of Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snyder, L.B. Health Communication Campaigns and Their Impact on Behavior. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2007, 39, S32–S40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, W.D.; Bingenheimer, J.; Cantrell, J.; Kreslake, J.; Tulsiani, S.; Ichimiya, M.; D’Esterre, A.P.; Gerard, R.; Martin, M.; Hair, E.C. Effects of a Social Media Intervention on Vaping Intentions: Randomized Dose-Response Experiment. J. Med. Internet Res. 2024, 26, e50741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virtual Lab Research. Available online: https://vlab.digital/ (accessed on 6 June 2024).

- Rath, J.M.; Romberg, A.R.; Perks, S.N.; Edwards, D.; Vallone, D.M.; Hair, E.C. Identifying message themes to prevent e-cigarette use among youth and young adults. Prev. Med. 2021, 150, 106683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, E.C.; Kreslake, J.M.; Rath, J.M.; Pitzer, L.; Bennett, M.; Vallone, D. Early evidence of the associations between an anti-e-cigarette mass media campaign and e-cigarette knowledge and attitudes: Results from a cross-sectional study of youth and young adults. Tob. Control 2023, 32, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottfried, J. Americans’ Social Media Use. 2024. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2024/01/31/americans-social-media-use/ (accessed on 18 November 2024).

- Donaldson, S.I.; Dormanesh, A.; Perez, C.; Majmundar, A.; Allem, J.-P. Association Between Exposure to Tobacco Content on Social Media and Tobacco Use: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2022, 176, 878–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thrul, J.; Tormohlen, K.N.; Meacham, M.C. Social media for tobacco smoking cessation intervention: A review of the literature. Curr. Addict. Rep. 2019, 6, 126–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Health and Human Services; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Tobacco Use Prevention Media Campaigns: Lessons Learned from Youth in Nine Countries; U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office of Smoking and Health: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2006.

- Smit, E.S.; Fidler, J.A.; West, R. The role of desire, duty, and intention in predicting attempts to quit smoking. Addiction 2010, 106, 844–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzilos, G.K.; Strong, D.R.; Abrantes, A.M.; Ramsey, S.E.; Brown, R.A. Quit intention as a predictor of quit attempts over time in adolescents with psychiatric disorders. Am. J. Addict. 2013, 23, 84–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Demographic Variable | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Treatment Groups | |

| 0 | 35 (21.88%) |

| 1 | 33 (20.62%) |

| 2 | 22 (13.75%) |

| 3 | 70 (43.75%) |

| Age | |

| 18–20 | 60 (37.50%) |

| 21–24 | 100 (62.50%) |

| Education | |

| Less than High School | 31 (19.38%) |

| High School | 82 (51.25%) |

| Bachelor’s or Greater | 43 (25.88%) |

| Missing/Refused | 4 (2.50%) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 116 (72.50%) |

| Male | 41 (25.62%) |

| Non-binary/different identity | 3 (1.88%) |

| Perceived Financial Status | |

| Do not meet basic expenses | 11 (6.88%) |

| Just meet basic expenses | 43 (26.88%) |

| Meet needs with a little left | 54 (33.75%) |

| Live comfortably | 52 (32.50%) |

| Race/Ethnicity | |

| Non-Hispanic White | 77 (48.12%) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 14 (8.75%) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 33 (20.62%) |

| Another Race/Ethnicity, including Multiracial | 36 (22.50%) |

| Means for Attitudes (Baseline)—mean (SD) | |

| Anti-Industry | 3.36 (1.01) |

| Risk Perception | 3.11 (1.16) |

| Independence from E-Cigarettes | 3.39 (0.97) |

| Social Unacceptability | 3.62 (0.96) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

D’Esterre, A.P.; Tulsiani, S.; Hair, E.C.; Aseltine, M.; Yu, L.Q.; Ichimiya, M.; Bingenheimer, J.B.; Cantrell, J.; Evans, W.D. Pathway from Exposure to an E-Cigarette Prevention Social Media Campaign to Increased Quitting Intentions: A Randomized Trial Among Young Adult E-Cigarette Users. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 307. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22020307

D’Esterre AP, Tulsiani S, Hair EC, Aseltine M, Yu LQ, Ichimiya M, Bingenheimer JB, Cantrell J, Evans WD. Pathway from Exposure to an E-Cigarette Prevention Social Media Campaign to Increased Quitting Intentions: A Randomized Trial Among Young Adult E-Cigarette Users. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(2):307. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22020307

Chicago/Turabian StyleD’Esterre, Alexander P., Shreya Tulsiani, Elizabeth C. Hair, Madeleine Aseltine, Linda Q. Yu, Megumi Ichimiya, Jeffrey B. Bingenheimer, Jennifer Cantrell, and W. Douglas Evans. 2025. "Pathway from Exposure to an E-Cigarette Prevention Social Media Campaign to Increased Quitting Intentions: A Randomized Trial Among Young Adult E-Cigarette Users" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 2: 307. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22020307

APA StyleD’Esterre, A. P., Tulsiani, S., Hair, E. C., Aseltine, M., Yu, L. Q., Ichimiya, M., Bingenheimer, J. B., Cantrell, J., & Evans, W. D. (2025). Pathway from Exposure to an E-Cigarette Prevention Social Media Campaign to Increased Quitting Intentions: A Randomized Trial Among Young Adult E-Cigarette Users. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(2), 307. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22020307