Midwifery Continuity of Care in Indonesia: Initiation of Mobile Health Development Integrating Midwives’ Competency and Service Needs

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Recruitment and Participants

2.3. Research Ethics

3. Results

3.1. Quantitative Research

3.2. Qualitative Research

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Maternal Mortality Evidence Brief; Department of Reproductive Health and Research, WHO Press: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019; Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/329886/WHO-RHR-19.20-eng (accessed on 3 September 2022).

- Ministry of Health. Indonesia Health Profile 2018. Available online: https://pusdatin.kemkes.go.id/resources/download/pusdatin/profil-kesehatan-indonesia/Data-dan-Informasi_Profil-Kesehatan-Indonesia-2018 (accessed on 3 September 2022).

- World Health Organization. Digital Education for Building Health Workforce Capacity; WHO Press: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240000476 (accessed on 3 September 2022).

- Forster, D.A.; McLachlan, H.L.; Davey, M.-A.; Biro, M.A.; Farrell, T.; Gold, L.; Flood, M.; Shafiei, T.; Waldenström, U. Continuity of care by a primary midwife (caseload midwifery) increases women’s satisfaction with antenatal, intrapartum and postpartum care: Results from the COSMOS randomised controlled trial. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2016, 16, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kuipers, Y.F.; van Beeck, E.; van den Berg, L.; Dijkhuizen, M. The comparison of the interpersonal action component of woman-centred care reported by healthy pregnant women in different sized practices in the Netherlands: A cross-sectional study. Women Birth 2021, 34, e376–e383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidane, A.; Getachew, T.; Mesfin, F.; Eyeberu, A.; Dheresa, M. Maternal satisfaction on delivery care services and associated factors at public hospitals in eastern Ethiopia. Int. Health 2022, ihac038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boli, R.V.T.; Lerik, M.D.C.; Muntasir, I.; Nalle, A.A. An Analysis of Continuity of Care Implementation at Tarus and Baumata Public Health Center, Kupang Regency. EAS J. Nurs. Midwefery 2020, 2, 332–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.; Chen, J.; Zhao, Y.; Qiu, C. Effect Analysis of Midwife Education and Training with PDCA Model. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2022, 2022, 7397186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isoyama, A.; Kinugawa, S. Midwives’ Training Needs for Providing Support to Japanese Childbearing Women and Family Members. Asian J. Hum. Serv. 2022, 22, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perriman, N.; Davis, D.L.; Ferguson, S. What women value in the midwifery continuity of care model: A systematic review with meta-synthesis. Midwifery 2018, 62, 220–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ismaila, Y.; Bayes, S.; Geraghty, S. Barriers to Quality Midwifery Care: A Systematic Review and Meta-Synthesis of Qualitative Data. Int. J. Childbirth 2021, 11, 84–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCaffery, S.; Small, K.; Gamble, J. Rural Australian Doctors’ Views About Midwifery and Midwifery Models of Care: A Qualitative Study. Int. J. Childbirth 2022, 12, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pace, C.A.; Crowther, S.; Lau, A. Midwife experiences of providing continuity of carer: A qualitative systematic review. Women Birth 2021, 35, e221–e232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastie, C.R.; Barclay, L. Early career midwives’ perception of their teamwork skills following a specifically designed, whole-of-degree educational strategy utilising groupwork assessments. Midwifery 2021, 99, 102997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdullahi, A.; Ajoge, N.S.; Abubakar, Y.; Ahmed, M.A. The Design of an Intelligent Healthcare Chatbot for Managing Ante-Natal Recommendations. Int. J. Innov. Sci. Res. Technol. 2022, 7, 1829–1834. [Google Scholar]

- Stellata, A.G.; Rinawan, F.R.; Winarno, G.N.A.; Susanti, A.I.; Purnama, W.G. Exploration of Telemidwifery: An Initiation of Application Menu in Indonesia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clayton, C.; Hemingway, A.; Hughes, M.; Rawnson, S. The public health role of caseloading midwives in reducing health inequalities in childbearing women and babies living in deprived areas in England. The Mi-CARE Study protocol. Eur. J. Midwifery 2022, 6, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Chavolla, L.J.; Thouvenot, V.I.; Schimpf, D.; Moritz, A. Adopting digital technology in midwifery practice–experiences and perspectives from six projects in eight countries (2014–2016). J. Int. Soc. Telemed. Ehealth 2019, 7, e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hainsworth, N.; Dowse, E.; Ebert, L.; Foureur, M. ‘Continuity of Care Experiences’ within pre-registration midwifery education programs: A scoping review. Women Birth 2021, 34, 514–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKeever, J.; Leider, J.P.; Alford, A.A.; Evans, D. Research Full Report: Regional Training Needs Assessment: A First Look at High-Priority Training Needs Across the United States by Region. J. Public Health Manag. Pract. 2019, 25, S166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiola, T.T.; Badjuka, B.Y.M. The Analysis of Village Midwife Performance in Reducing Maternal and Infant Mortality Rate. J. Adm. Kesehat. Indones. 2020, 8, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makhado, L.C.; Mangena-Netshikweta, M.L.; Mulondo, S.A.; Olaniyi, F.C. The Roles of Obstetrics Training Skills and Utilisation of Maternity Unit Protocols in Reducing Perinatal Mortality in Limpopo Province, South Africa. Healthcare 2022, 10, 662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, B.; Hildingsson, I.; Johansson, E.; Christensson, K. Self-assessed confidence of students on selected midwifery skills: Comparing diploma and bachelors programmes in one province of India. Midwifery 2018, 67, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maude, R.; Douché, J.; Holloway, K. Midwives’ perspectives on the benefits for women and babies following completion of midwifery postgraduate complex care education. N. Z. Coll. Midwives J. 2022, 58, 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnair, N.M.A.; Malik, E.M.; Ahmed, M.E.; Abu, I.I.M. Training Needs Assessment for Nurses in Sennar State, Sudan: Cross Sectional Study (1). Sci. J. Public Health 2019, 7, 104–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goshu, M.; Godefay, H.; Bihonegn, F.; Ayalew, F.; Haileselassie, D.; Kebede, A.; Temam, G.; Gidey, G. Assessing the competence of midwives to provide care during labor, childbirth and the immediate postpartum period–A cross sectional study in Tigray region, Ethiopia. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0206414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishimwe, A.; Ibisomi, L.; Nyssen, M.; Conco, D.N. The effect of an mLearning application on nurses’ and midwives’ knowledge and skills for the management of postpartum hemorrhage and neonatal resuscitation: Pre–post intervention study. Hum. Resour. Health 2021, 19, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osei, E.; Mashamba-Thompson, T.P. Mobile health applications for disease screening and treatment support in low-and middle-income countries: A narrative review. Heliyon 2021, 7, e06639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussain, M.; Zaidan, A.; Zidan, B.; Iqbal, S.; Ahmed, M.; Albahri, O.S.; Albahri, A.S. Conceptual framework for the security of mobile health applications on android platform. Telemat. Inform. 2018, 35, 1335–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begam, A.A.A.; Tholappan, A. Psychomotor domain of Bloom’s taxonomy in teacher education. Shanlax Int. J. Educ. 2018, 6, 11–14. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, N. Outcome-based education: An outline. High. Educ. Future 2020, 7, 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gegenfurtner, A.; Ebner, C. Webinars in higher education and professional training: A meta-analysis and systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Educ. Res. Rev. 2019, 28, 100293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goemaes, R.; Beeckman, D.; Verhaeghe, S.; Van Hecke, A. Sustaining the quality of midwifery practice in Belgium: Challenges and opportunities for advanced midwife practitioners. Midwifery 2020, 89, 102792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFadden, A.; Gupta, S.; Marshall, J.L.; Shinwell, S.; Sharma, B.; McConville, F.; MacGillivray, S. Systematic review of barriers to, and facilitators of, the provision of high-quality midwifery services in India. Birth 2020, 47, 304–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateus-Coelho, N.; Cruz-Cunha, M.M.; Ávila, P. Application of the Industry 4.0 technologies to mobile learning and health education apps. FME Trans. 2021, 49, 876–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syahrullah, S. Aplikasi E-Kohort Register Kesehatan Ibu Dan Anak (KIA) Pada Puskesmas Nosarara Kota Palu. JATISI (J. Tek. Inform. Dan Sist. Inf.) 2018, 5, 74–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuliarti, F.; Waluyo, A.; Prahastuti, B.S. Utilization of Tele-CTG for Strengthening Maternal Health Service During The COVID-19 Pandemic: Case Study in Kupang Regency, Indonesia. ITTPCOVID19 2021, 1, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Rinawan, F.R.; Susanti, A.I.; Amelia, I.; Ardisasmita, M.N.; Dewi, R.K.; Ferdian, D.; Purnama, W.G.; Purbasari, A. Understanding mobile application development and implementation for monitoring Posyandu data in Indonesia: A 3-year hybrid action study to build “a bridge” from the community to the national scale. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balakrishnan, R.; Gopichandran, V.; Chaturvedi, S.; Chatterjee, R.; Mahapatra, T.; Chaudhuri, I. Continuum of Care Services for Maternal and Child Health using mobile technology—A health system strengthening strategy in low and middle income countries. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2016, 16, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Martinez, B.; Ixen, E.C.; Hall-Clifford, R.; Juarez, M.; Miller, A.C.; Francis, A.; Valderrama, C.E.; Stroux, L.; Clifford, G.D.; Rohloff, P. mHealth intervention to improve the continuum of maternal and perinatal care in rural Guatemala: A pragmatic, randomized controlled feasibility trial. Reprod. Health 2018, 15, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kusyanti, T.; Wirakusumah, F.F.; Rinawan, F.R.; Muhith, A.; Purbasari, A.; Mawardi, F.; Puspitasari, I.W.; Faza, A.; Stellata, A.G. Technology-Based (Mhealth) and Standard/Traditional Maternal Care for Pregnant Woman: A Systematic Literature Review. Healthcare 2022, 10, 1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qudah, B.; Luetsch, K. The influence of mobile health applications on patient-healthcare provider relationships: A systematic, narrative review. Patient Educ. Couns. 2019, 102, 1080–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinawan, F.R.; Faza, A.; Susanti, A.I.; Purnama, W.G.; Indraswari, N.; Ferdian, D.; Fatimah, S.N.; Purbasari, A.; Zulianto, A.; Sari, A.N. Posyandu Application for Monitoring Children Under-Five: A 3-Year Data Quality Map in Indonesia. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2022, 11, 399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farao, J.; Malila, B.; Conrad, N.; Mutsvangwa, T.; Rangaka, M.X.; Douglas, T.S. A user-centred design framework for mHealth. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0237910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemei, J.; Etowa, J. Continuing professional development: Perspectives of Kenyan nurses and midwives. Open J. Nurs. 2021, 11, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renning, K.; van de Water, B.; Brandstetter, S.; Kasitomu, C.; Gowero, N.; Simbota, M.; Majamanda, M. Training needs assessment for practicing pediatric critical care nurses in Malawi to inform the development of a specialized master’s education pathway: A cohort study. BMC Nurs. 2022, 21, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, S.; Cant, R.; Porter, J.; Bogossian, F.; McKenna, L.; Brady, S.; Fox-Young, S. Simulation based learning in midwifery education: A systematic review. Women Birth 2012, 25, 64–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mildon, A.; Sellen, D. Use of mobile phones for behavior change communication to improve maternal, newborn and child health: A scoping review. J. Glob. Health 2019, 9, 020425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zemmel, D.J.; Kulik, P.K.; Leider, J.P.; Power, L.E. Public Health Workforce Development During and Beyond the COVID-19 Pandemic: Findings From a Qualitative Training Needs Assessment. J. Public Health Manag. Pract. 2022, 28, S263–S270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decree of Indonesian Minister of Health of The Republic of Indonesia Number 320 Years 2020 Concerning Midwife Professional Standards. 15 May 2020. Available online: https://ktki.kemkes.go.id/info/sites/default/files/KEPMENKES%20320%20TAHUN%202020%20TENTANG%20STANDAR%20PROFESI%20BIDAN (accessed on 3 September 2022).

- Howlett, G.; Waemusa, Z. Digital native/digital immigrant divide: EFL teachers’ mobile device experiences and practice. Contemp. Educ. Technol. 2018, 9, 374–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fontein-Kuipers, Y.; Romeijn, E.; Zwijnenberg, A.; Eekhof, W.; van Staa, A. ‘ISeeYou’: A woman-centred care education and research project in Dutch bachelor midwifery education. Health Educ. J. 2018, 77, 899–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angeline, T.; TogarepiAnoldis, M.G.; Mary, B. Midwifery Competency: Concept Paper. Int. J. Bus. Manag. Econ. Rev. 2019, 2, 11–16. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Mapping of WHO Competencies for the Maternal and Newborn Health (MNH) Professional Based on Previously Published International Standards: Web Appendix to Defining Competent Maternal and Newborn Health Professionals: Background Document to the 2018 Joint Statement by WHO, UNFPA, UNICEF, ICM, ICN, FIGO and IPA: Definition of Skilled Health Personnel Providing Care during Childbirth; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018; Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/272819 (accessed on 3 September 2022).

- Fernandez Turienzo, C.; Silverio, S.A.; Coxon, K.; Brigante, L.; Seed, P.T.; Shennan, A.H.; Sandall, J.; Group, P.C. Experiences of maternity care among women at increased risk of preterm birth receiving midwifery continuity of care compared to women receiving standard care: Results from the POPPIE pilot trial. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0248588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummins, A.; Griew, K.; Devonport, C.; Ebbett, W.; Catling, C.; Baird, K. Exploring the value and acceptability of an antenatal and postnatal midwifery continuity of care model to women and midwives, using the Quality Maternal Newborn Care Framework. Women Birth 2022, 35, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law Number 4 Year 2019, 15 March 2019. Available online: https://ktki.kemkes.go.id/info/sites/default/files/UU%20Nomor%204%20Tahun%202019%20ttg%20Kebidanan (accessed on 3 September 2022).

- Gamble, J.; Browne, J.; Creedy, D.K. Hospital accreditation: Driving best outcomes through continuity of midwifery care? A scoping review. Women Birth 2020, 34, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toohill, J.; Chadha, Y.; Nowlan, S. An interactive decision-making framework (i-DMF) to scale up maternity continuity of carer models. J. Res. Nurs. 2020, 25, 561–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, J.; Taylor, J.; Browne, J.; Ferguson, S.; Atchan, M.; Maher, P.; Homer, C.S.; Davis, D. The future in their hands: Graduating student midwives’ plans, job satisfaction and the desire to work in midwifery continuity of care. Women Birth 2020, 33, e59–e66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neke, N.M.; Gadau, G.; Wasem, J. Policy makers’ perspective on the provision of maternal health services via mobile health clinics in Tanzania—Findings from key informant interviews. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0203588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavine, A.; MacGillivray, S.; McConville, F.; Gandhi, M.; Renfrew, M.J. Pre-service and in-service education and training for maternal and newborn care providers in low-and middle-income countries: An evidence review and gap analysis. Midwifery 2019, 78, 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilty, D.M.; Chan, S.; Torous, J.; Luo, J.; Boland, R.J. A telehealth framework for mobile health, smartphones, and apps: Competencies, training, and faculty development. J. Technol. Behav. Sci. 2019, 4, 106–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Lu, H.; Zhao, Y.; Ren, L.; Cao, L.; Pang, D.; Wang, A. Core competencies of the midwifery workforce in China: A scoping review. J. Nurs. Manag. 2022, 30, 535–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Lu, H.; Li, J.; Zhou, N.; Zang, Y.; Ren, L.; Wang, J. Comparison of midwives’ self-perceived essential competencies between low and high maternal mortality ratio provinces in China. J. Clin. Nurs. 2020, 29, 4733–4747. [Google Scholar]

- Tarimo, E.A.; Moyo, G.; Masenga, H.; Magesa, P.; Mzava, D. Performance and self-perceived competencies of enrolled nurse/midwives: A mixed methods study from rural Tanzania. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2018, 18, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- International Confederation of Midwives. Essential Competencies for Midwifery Practice. October 2018. Available online: https://www.internationalmidwives.org/assets/files/general-files/2019/02/icm-competencies_english_final_jan-2019-update_final-web_v1.0.pdf (accessed on 3 September 2022).

- Hyasat, A.S.; Al-Weshah, G.A.; Kakeesh, D.F. Training Needs Assessment for Small Businesses: The Case of the Hospitality Industry in Jordan. Geo J. Tour. Geosites 2022, 40, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joly, B.M.; Coronado, F.; Bickford, B.C.; Leider, J.P.; Alford, A.; McKeever, J.; Harper, E. A review of public health training needs assessment approaches: Opportunities to move forward. J. Public Health Manag. Pract. JPHMP 2018, 24, 571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medina, M.; Lee, D.; Garza, D.M.; Goldwaser, E.L.; Truong, T.T.; Apraku, A.; Cosgrove, J.; Cooper, J.J. Neuroimaging education in psychiatry residency training: Needs assessment. Acad. Psychiatry 2020, 44, 311–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dashora, U.; Huw, A.D.; Bennett, S.; Goodchild, A.; Hugason-Briem, J.; Johnson, G.; Kitt, A.; Schreiner, A.; Todd, D.; Yiallorous, J. Findings of a nationwide survey of the diabetes education and training needs of midwives in the UK. Br. J. Diabetes 2018, 18, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garti, I.; Gray, M.; Tan, J.-Y.; Bromley, A. Midwives’ knowledge of pre-eclampsia management: A scoping review. Women Birth 2021, 34, 87–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soggiu-Duta, C.L.; Suciu, N. Resident physicians’ and midwives’ knowledge of preeclampsia and eclampsia reflected in their practice at a clinical hospital in southern Romania. J. Med. Life 2019, 12, 435. [Google Scholar]

- Abdelgadir, N.I.; Brier, S.L.; Abdelgadir, W.I.; Mohammed, S.A. The effect of training program on midwives practice concerning timely management of postpartum Hemorrhage at Aljenena town Dafur. Nat. Med. Sci. 2022, 21, 49–56. [Google Scholar]

- Ameh, C.A.; Mdegela, M.; White, S.; van den Broek, N. The effectiveness of training in emergency obstetric care: A systematic literature review. Health Policy Plan. 2019, 34, 257–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mustamin, M.; Amiruddin, R.; Palutturi, S.; Rahman, S.A.; Risnah, R. Training effect to the knowledge and skills of midwives in maternity health services at primary health care. Int. J. Community Med. Public Health 2018, 5, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Baumgartner, J.N.; Headley, J.; Kirya, J.; Guenther, J.; Kaggwa, J.; Kim, M.K.; Aldridge, L.; Weiland, S.; Egger, J. Impact evaluation of a maternal and neonatal health training intervention in private Ugandan facilities. Health Policy Plan. 2021, 36, 1103–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilty, D.M.; Maheu, M.M.; Drude, K.P.; Hertlein, K.M. The need to implement and evaluate telehealth competency frameworks to ensure quality care across behavioral health professions. Acad. Psychiatry 2018, 42, 818–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Grimwood, T.; Snell, L. The use of technology in healthcare education: A literature review. MedEdPublish 2020, 9, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knitza, J.; Simon, D.; Lambrecht, A.; Raab, C.; Tascilar, K.; Hagen, M.; Kleyer, A.; Bayat, S.; Derungs, A.; Amft, O. Mobile health usage, preferences, barriers, and eHealth literacy in rheumatology: Patient survey study. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2020, 8, e19661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Allman-Farinelli, M. Impact of training and integration of apps into dietetic practice on dietitians’ self-efficacy with using mobile health apps and patient satisfaction. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2019, 7, e12349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Handayani, M.N.; Kamis, A.; Ali, M.; Wahyudin, D.; Mukhidin, M. Development of green skills module for meat processing technology study. J. Food Sci. Educ. 2021, 20, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; Disman, A.P.; Hadiapurwa, A.; Risdiyanto, H.L. Blended Learning in the Implementation of Environment Dimension of ESD Infused into Junior High School Science. J. Hunan Univ. Nat. Sci. 2022, 49, 139–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osei, E.; Agyei, K.; Tlou, B.; Mashamba-Thompson, T.P. Availability and Use of Mobile Health Technology for Disease Diagnosis and Treatment Support by Health Workers in the Ashanti Region of Ghana: A Cross-Sectional Survey. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.L.; Gong, E.; Gu, W.; Turner, E.L.; Gallis, J.A.; Zhou, Y.; Li, Z.; McCormack, K.E.; Xu, L.-Q.; Bettger, J.P. Effectiveness of a primary care-based integrated mobile health intervention for stroke management in rural China (SINEMA): A cluster-randomized controlled trial. PLoS Med. 2021, 18, e1003582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nezamdoust, S.; Abdekhoda, M.; Rahmani, A. Determinant factors in adopting mobile health application in healthcare by nurses. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2022, 22, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slovensky, D.J.; Malvey, D.M.; Neigel, A.R. A model for mHealth skills training for clinicians: Meeting the future now. Mhealth 2017, 3, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vermeulen, J.; Luyben, A.; O’Connell, R.; Gillen, P.; Escuriet, R.; Fleming, V. Failure or progress?: The current state of the professionalisation of midwifery in Europe. Eur. J. Midwifery 2019, 3, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Zhang, Y.; Ye, Z.; Huang, L.; Zheng, X. Development of a Mobile Application of Internet-Based Support Program on Parenting Outcomes for Primiparous Women. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, A.; Knight, L.; McKeown, A.; Cliffe, C.; Arora, A.; Crampton, P. A postgraduate curriculum for integrated care: A qualitative exploration of trainee paediatricians and general practitioners’ experiences. BMC Med. Educ. 2019, 19, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imanipour, M.; Ebadi, A.; Monadi Ziarat, H.; Mohammadi, M.M. The effect of competency-based education on clinical performance of health care providers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 2022, 28, e13003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bäck, L.; Hildingsson, I.; Sjöqvist, C.; Karlström, A. Developing competence and confidence in midwifery-focus groups with Swedish midwives. Women Birth 2017, 30, e32–e38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Higman, S.; Dwivedi, V.; Nsaghurwe, A.; Busiga, M.; Sotter Rulagirwa, H.; Smith, D.; Wright, C.; Nyinondi, S.; Nyella, E. Designing interoperable health information systems using enterprise architecture approach in resource-limited countries: A literature review. Int. J. Health Plan. Manag. 2019, 34, e85–e99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memon, Z.; Tahir, F.; Dehraj, S.; Noureen, F.; Jalbani, A.H.; Bux, K. Multi interactive chatbot communication framework for health care. Int. J. Comput. Sci. Netw. Secur. 2020, 20, 121–124. [Google Scholar]

| Phase | Procedure | Output |

|---|---|---|

| Quantitative |

|

|

| ||

| Qualitative |

|

|

| ||

| Explanatory sequential mixed method |

|

|

| Characteristics | f | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age * | ||

| • ≤35 years | 220 | 58.98 |

| • >35 years | 153 | 41.02 |

| Years of experience | ||

| • <1–5 years | 68 | 18.23 |

| • 6–10 years | 95 | 25.47 |

| • >10 years | 210 | 56.30 |

| Education level | ||

| • Diploma degree (D3) | 269 | 72.12 |

| • Bachelor’s degree (D4/S1) | 88 | 23.59 |

| • Profession | 9 | 2.41 |

| • Master’s degree (S2) | 7 | 1.88 |

| How long does it take to use a smartphone every day? | ||

| • 1–12 h/day | 292 | 78.28 |

| • 13–24 h/day | 81 | 21.72 |

| Smartphones are used for: | ||

| • Learning | 35 | 9.38 |

| • Social media | 105 | 28.15 |

| • Health services | 92 | 24.66 |

| • Others | 141 | 37.80 |

| Scope of Competency MCOC | ||

| • Antenatal Care | 20 | 5.36 |

| • Intranatal Care | 31 | 8.31 |

| • Newborn and Postpartum Care | 5 | 1.34 |

| • Early detection and treatment of risk complications | 317 | 84.99 |

| No. | Competence | Competency Indicator | Mean ± SD | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Antenatal care/Pregnancy | 1. Early detection in pregnancy | 3.86 ± 0.35 | 3.00 | 4.00 |

| 2. Communication, information, and education on the danger signs of pregnancy | 3.82 ± 0.39 | 3.00 | 4.00 | ||

| 3. Counseling for planning delivery and prevention of complications | 3.80 ± 0.41 | 3.00 | 4.00 | ||

| 2 | Intranatal Care/Childbirth | 4. Early labor screening | 3.78 ± 0.41 | 3.00 | 4.00 |

| 5. Labor monitoring with partograph | 3.85 ± 0.36 | 3.00 | 4.00 | ||

| 6. IV stage of labor monitoring | 3.84 ± 0.37 | 3.00 | 4.00 | ||

| 7. Early management of the most common emergency cases in labor | 3.74 ± 0.49 | 1.00 | 4.00 | ||

| 3 | Newborn Care | 8. Identification of disease problems in newborns | 3.65 ± 0.56 | 1.00 | 4.00 |

| 9. Identify high-risk babies | 3.68 ± 0.53 | 1.00 | 4.00 | ||

| 10. Caring for newborns with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) mothers | 3.42 ± 0.75 | 1.00 | 4.00 | ||

| 11. Care of newborns with hepatitis mothers | 3.45 ± 0.80 | 1.00 | 4.00 | ||

| 12. Newborn care with syphilis mother | 3.52 ± 0.62 | 1.00 | 4.00 | ||

| 13. Pre-referral baby stabilization | 3.67 ± 0.48 | 2.00 | 4.00 | ||

| 14. Early management of premature babies | 3.67 ± 0.51 | 1.00 | 4.00 | ||

| 15. Management of resuscitation | 3.78 ± 0.46 | 1.00 | 4.00 | ||

| 16. Early management of newborns | 3.70 ± 0.48 | 1.00 | 4.00 | ||

| 17. Identify referral needs | 3.66 ± 0.49 | 2.00 | 4.00 | ||

| 4 | Postpartum Care | 18. Identify problems during the puerperium | 3.67 ± 0.49 | 1.00 | 4.00 |

| 19. Communication, information, and education about the danger signs of puerperium | 3.72 ± 0.47 | 1.00 | 4.00 | ||

| 20. Early management in the puerperium with complications | 3.65 ± 0.52 | 1.00 | 4.00 | ||

| 21. Psychosocial support for mothers who have lost their babies | 3.67 ± 0.49 | 2.00 | 4.00 | ||

| 22. Early management of emergency cases during the puerperium | 3.67 ± 0.49 | 2.00 | 4.00 |

| Characteristics | Distribution |

|---|---|

| Gender | 13 females |

| Age | Mean age: (range 28–50 years) |

| Employment status | Coordinator midwife: 6 Village midwife: 7 |

| Years of service | <7 years: 1 ≥7 years: 12 |

| Last education | Diploma 3 midwifery: 7 Diploma 4 midwifery: 5 Magister public health: 1 |

| Job placement | Urban: 4 Rural: 9 |

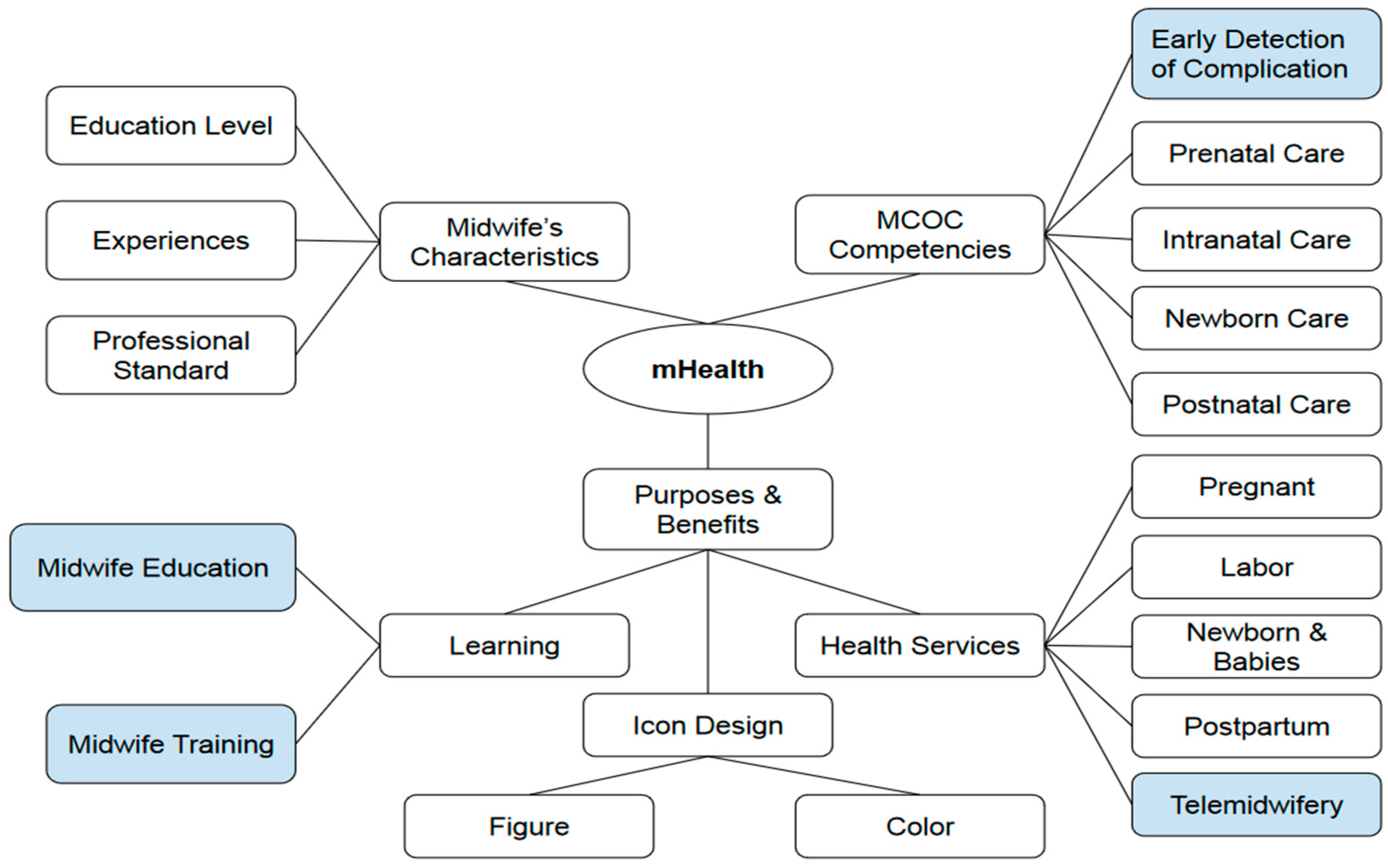

| Theme | Sub Themes | Quotations |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Midwife’s Characteristics | i. Education Level | i. Midwife skills must be continuously improved with training and education (Informant B.1) |

| ii. Experiences | ii. Midwives continue to learn as their experience increases (Informant B.2) | |

| iii. Professional standards | iii. Midwives can sometimes carry out treatment based on authority but are not yet competent (Informant B.3) | |

| 2. MCOC Competencies | i. Early detection and treatment of risk complications | i. Village midwives carry out the initial handling of complications of pregnancy, childbirth, newborns, and postpartum based on authority but are not yet competent. A referral is made if a case is handled outside the village midwife’s power (Informant B.2) |

| ii. Prenatal Care | ii. Not all midwives can attend integrated antenatal care training (Informant B.4) | |

| iii. Intranatal Care | iii. Midwives should provide education to patients about preparation for delivery (Informant B.4) | |

| iv. Newborn Care | iv. Need continuous monitoring of newborns until the baby is 28 days old (Informant A.1) | |

| v. Postnatal Care | v. Midwives need to provide education about postpartum repeatedly (Informant B.1) | |

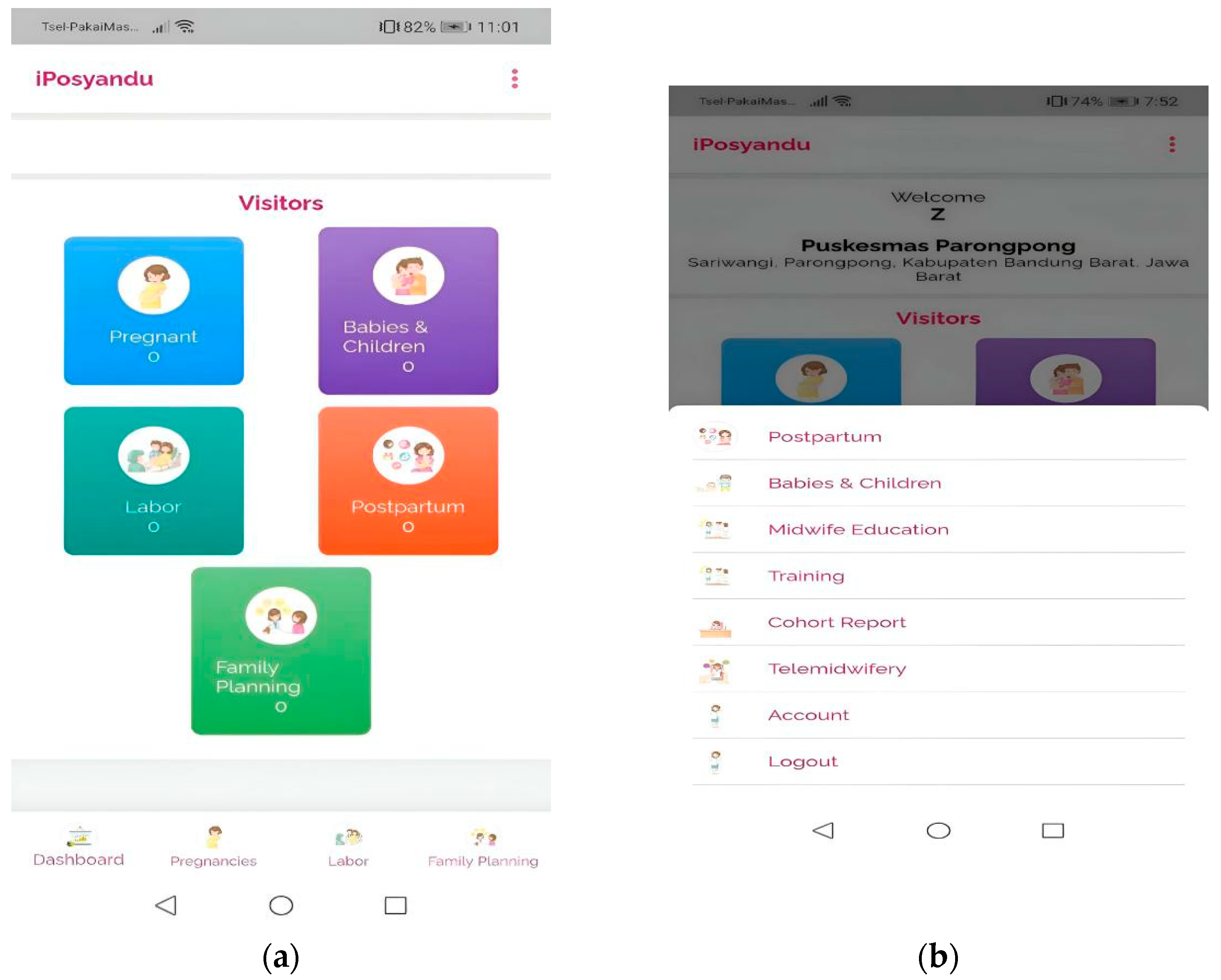

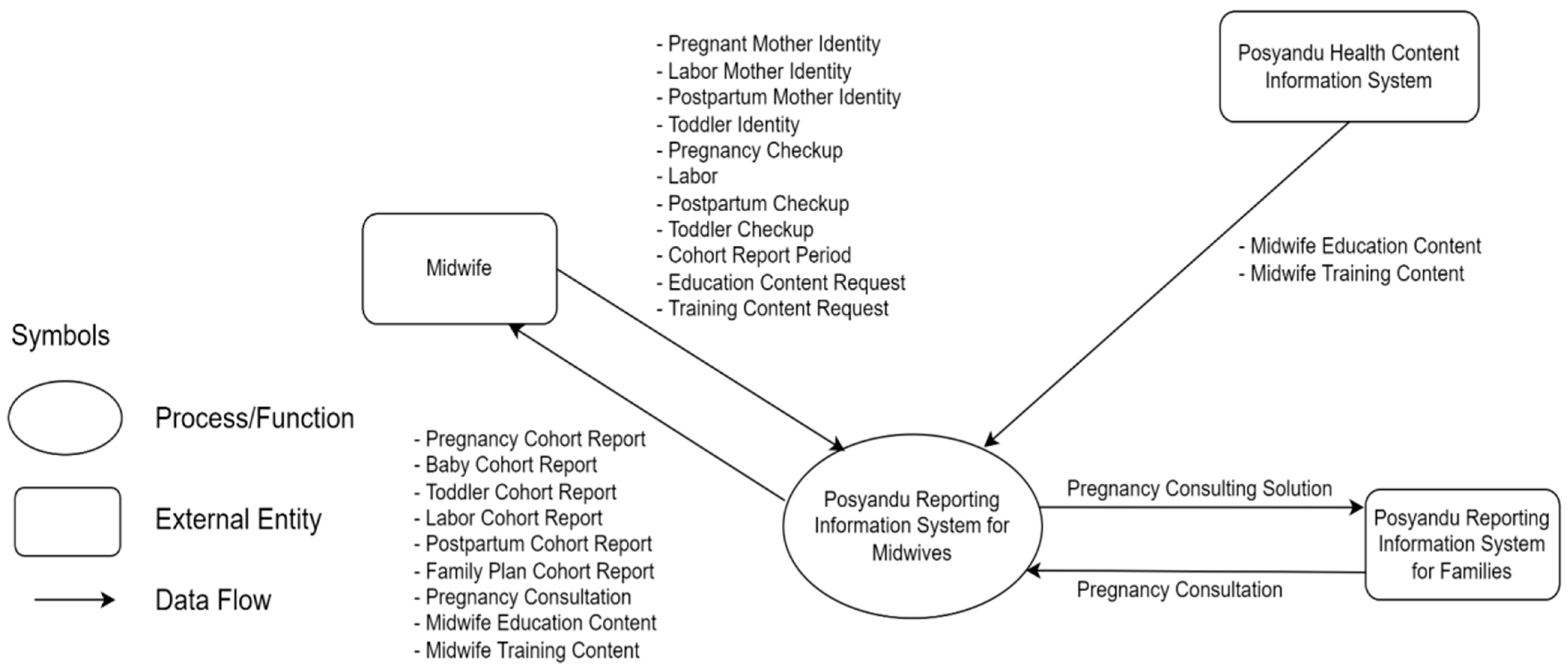

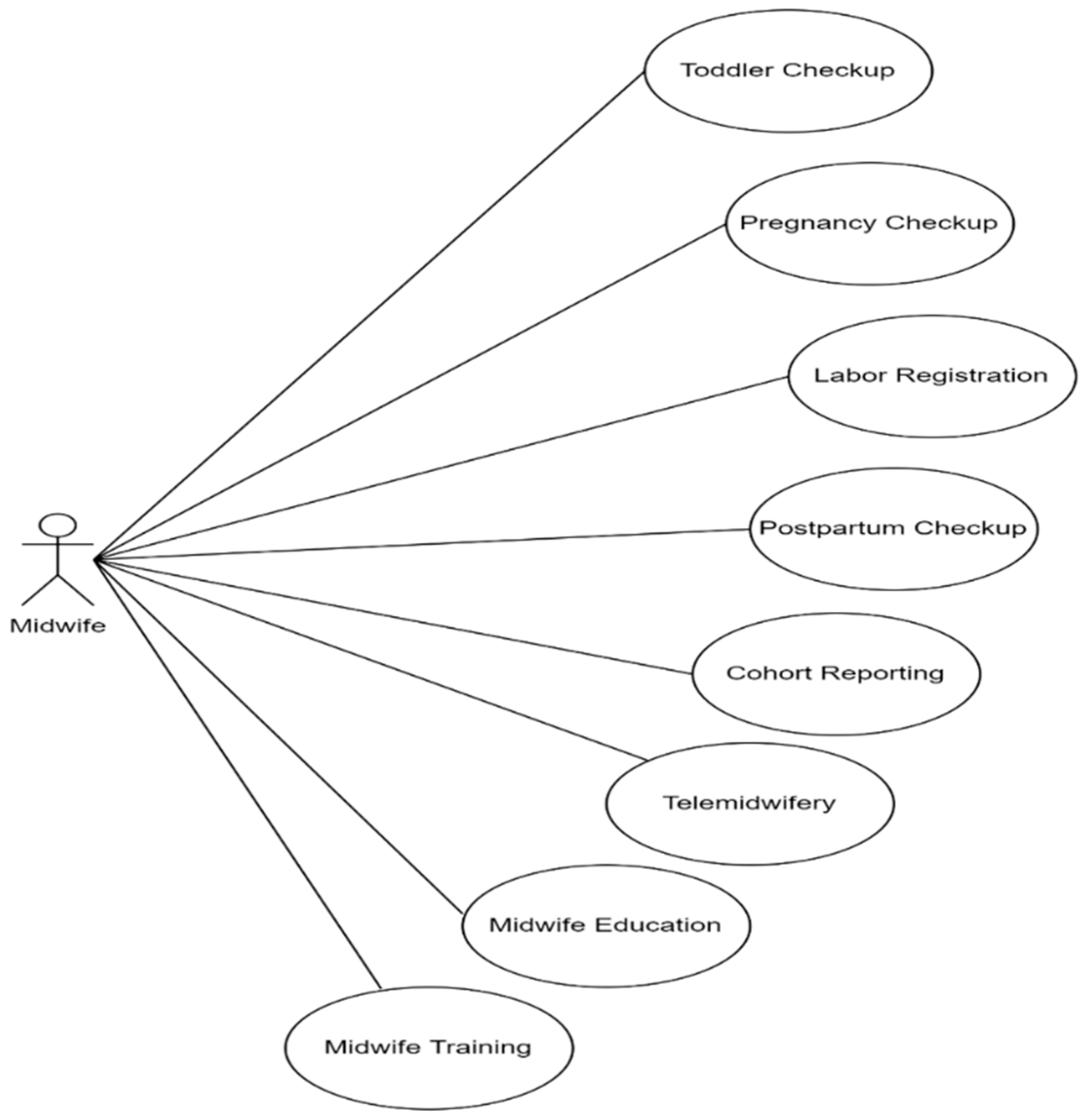

| 3. mHealth | 1. Purposes and benefits | i. So we need an application for continuity care starting from pregnancy, childbirth, or visits to make it easier because the application is on a handphone, so you can take it anywhere to make the midwife’s job easier (Informant A.1) |

| ii. Continuity midwifery care must be applied, making it easy to find out the mother is in labor (Informant A.4) | ||

| iii. Update knowledge with training (Informant B.2) | ||

| iv. The dissemination of the training results is shared via the bidan (Informant A.2) | ||

| v. Recording and reporting the nutritional status of infants and toddlers using the application (Informant A.3) | ||

| 2. Learning | ||

| i. Midwife Education | i. There should be an education menu for midwives in the application so that at least village midwives get initial knowledge before training. The training menu should be more experiential than that (the education menu) (Informant B.5) | |

| ii. Midwife training | ii. The training menu should be more experiential than that (the education menu) (Informant B.5) iii. Training materials in the form of modules for theory and videos for skills (Informant A.5) | |

| 3. Health services | ||

| i. Pregnant | i. There is historical data or information for pregnant women. (Informant B.6) | |

| ii. Labor | ii. Because it was continuous on the delivery date, there were complications or not, according to the cohort (Informant-A.1) | |

| iii. Postpartum | iii. Used for postpartum maternal health monitoring. (Informant A.1) | |

| iv. Babies and children | iv. Requires baby and toddler nutrition data. (Informant A.3) | |

| v. Telemidwifery | v. Communication with doctors, nutritionists, and health promotion the applications from the applications. (Informant A.6) vi. The continuity of care menu must be sequential, starting from detection and then handling, then up to referral. (Informant B.5) vii. Prepare answers automatically in the app from frequently asked questions, mom. (Informant A.1) | |

| 4. Icon | ||

| i. Figure/image | i. There are pictures of pregnant women. Then there are pictures of midwives and fathers. (Informant A.3) | |

| ii. Color application | ii. The application’s color follows the color of the Mother and Child Health book. (Informant A.7) | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Susanti, A.I.; Ali, M.; Hernawan, A.H.; Rinawan, F.R.; Purnama, W.G.; Puspitasari, I.W.; Stellata, A.G. Midwifery Continuity of Care in Indonesia: Initiation of Mobile Health Development Integrating Midwives’ Competency and Service Needs. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13893. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192113893

Susanti AI, Ali M, Hernawan AH, Rinawan FR, Purnama WG, Puspitasari IW, Stellata AG. Midwifery Continuity of Care in Indonesia: Initiation of Mobile Health Development Integrating Midwives’ Competency and Service Needs. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(21):13893. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192113893

Chicago/Turabian StyleSusanti, Ari Indra, Mohammad Ali, Asep Herry Hernawan, Fedri Ruluwedrata Rinawan, Wanda Gusdya Purnama, Indriana Widya Puspitasari, and Alyxia Gita Stellata. 2022. "Midwifery Continuity of Care in Indonesia: Initiation of Mobile Health Development Integrating Midwives’ Competency and Service Needs" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 21: 13893. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192113893

APA StyleSusanti, A. I., Ali, M., Hernawan, A. H., Rinawan, F. R., Purnama, W. G., Puspitasari, I. W., & Stellata, A. G. (2022). Midwifery Continuity of Care in Indonesia: Initiation of Mobile Health Development Integrating Midwives’ Competency and Service Needs. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(21), 13893. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192113893