The Rapid Adaptation and Optimisation of a Digital Behaviour-Change Intervention to Reduce the Spread of COVID-19 in Schools

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- To explore the experiences of students, school staff, and parents and their perceptions of behavioural recommendations relevant to COVID-19.

- To explore reactions to—and beliefs about—the content, structure, and format of Germ Defence.

- To use these insights to adapt Germ Defence in line with user experience, and as a result, develop an intervention that is acceptable, persuasive, and feasible amongst school communities.

2. Materials and Methods

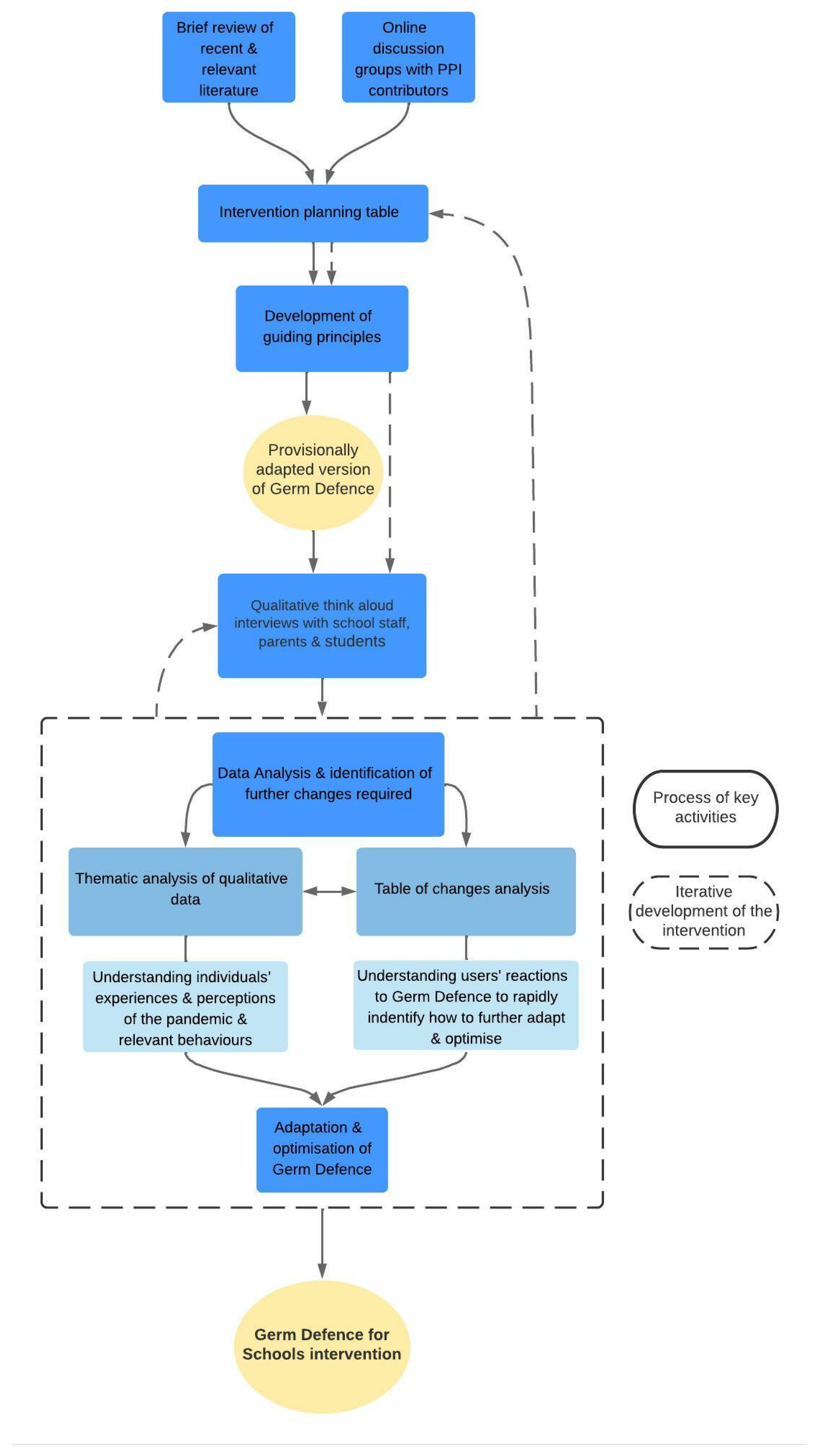

- Collating evidence from relevant literature and input from Patient and Public Involvement (PPI) contributors to inform guiding principles and provisional intervention adaptations

- In-depth qualitative think-aloud interviews with school staff, parents, and students

- Analysis of this qualitative data to provide further understanding of these individuals’ experiences and perceptions of the pandemic and relevant behaviours, and to inform how Germ Defence could be further adapted and optimised.

- Collating evidence and PPI input to inform Guiding Principles

- II.

- In-depth qualitative think-aloud interviews

- III.

- Data Analysis and identification of further changes required

- Thematic analysis allowed us to gain an in-depth understanding of users’ experiences of the pandemic and perceptions of relevant behaviours in order to inform later refinement of intervention content and messages.

- Table of changes analysis aimed to provide a rapid understanding of individuals’ reactions to, and perceptions of, the intervention content to identify necessary alterations and their relative importance. All interviews were transcribed verbatim with all identifiable data removed.

3. Results

3.1. Collating Evidence and PPI Input to Inform Guiding Principles

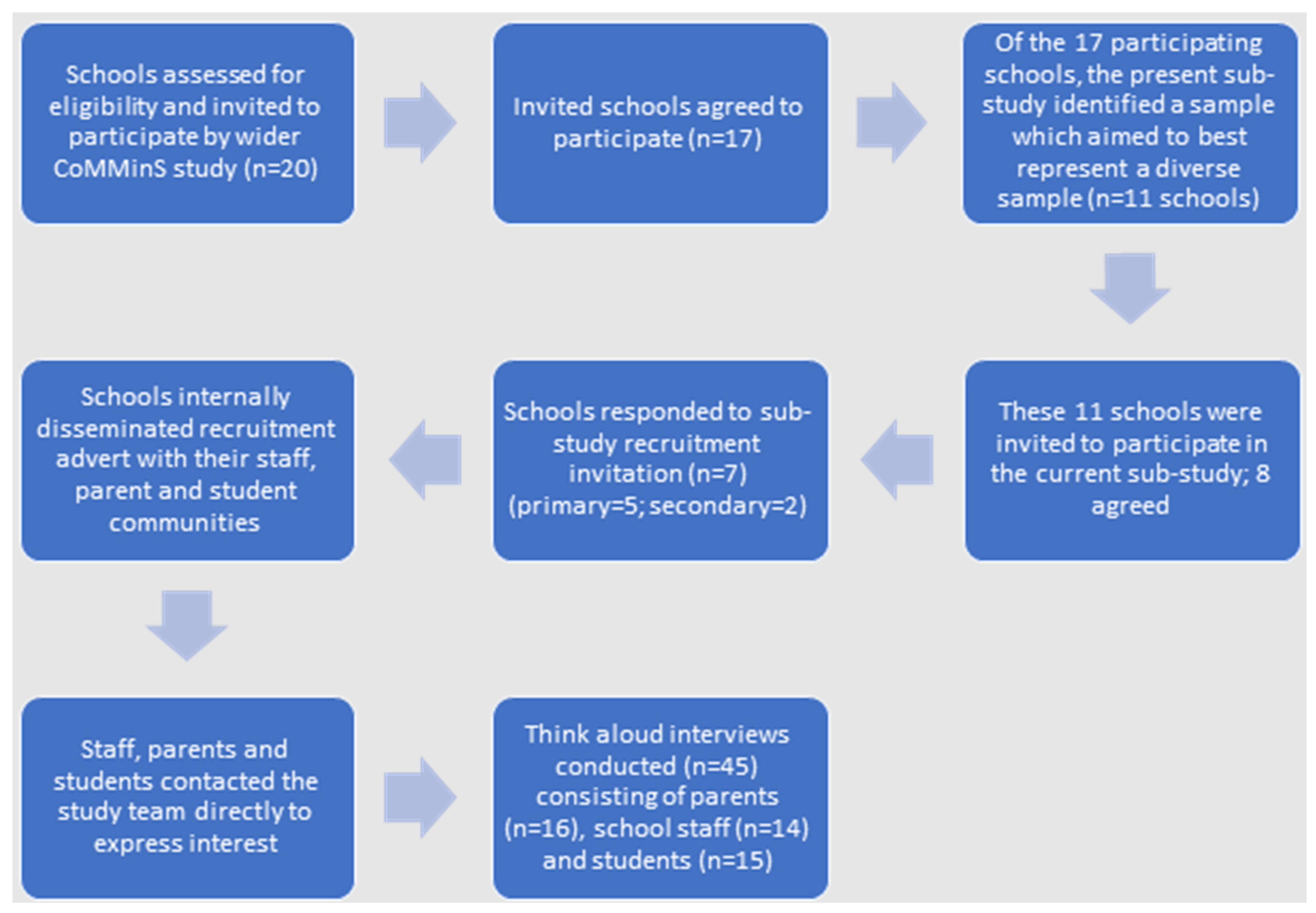

3.2. In-Depth Qualitative Think-Aloud Interviews

3.3. Data Analysis and Identification of Further Changes Required

3.3.1. Thematic Analysis

I think you do need to try and stay in control of what is actually a safe thing to do and what is a practical thing to do. Particularly around the home, if you’re not having visitors in and out and it’s your own family bubble, then I think you can be relatively secure in your own home.(P8)

I don’t think it’s [social distancing] necessary as a household because you live together and you do everything together. I don’t think it’s the right place to say do it in your house because you have bubbles and you’re in the bubble with your house so you don’t really need to be two metres apart in your home against your family.(C4)

We had a debate in the tutor group about it and it was so surprising. The students did not want to wear them [face coverings]. You had probably about a third that were like, ‘well I’m doing it not just for myself but for other people and for my nan etc.’, and then there were others going, ‘I don’t see why I should have to, I’ve not got it.’…There was a lot of resistance from the students, and it was very difficult to get them to wear masks in the corridors and things.(T14)

Well I’ve mostly been social distancing at school and everywhere, been wearing a mask when I go into shops because I’m over 11 now, and I’ve been mostly staying up in my bedroom on my computer.(C7)

I think I obviously didn’t think that much about ‘in the house’. I think I felt the house is my safe space and that once we were indoors, we were kind of fine, but I think I should think about that more really. About spreading the virus indoors between our bubbles.(P7)

I don’t want to wear face coverings at home…because it feels like a safe place, because they’re horrible to wear, and because I would think that because we don’t have people in the at-risk category in our household.(P10)

It’s your own home and you feel like you’re just safe in here(C12)

I think if you’re at school, you’ve got definitely a bigger risk on your shoulders because if you do something wrong or someone else does something wrong, you’re endangering quite a lot of people there…when you’re at home I mean it’s really important, but you’re endangering less people when you’re doing it at home.(C2)

A lot of the parents around here didn’t really take it very seriously at the start. I found myself getting a lot more anxious about it and then with the children coming in and then seeing them out and about and not following the rules, scared me even more.(T12)

So they were in bubbles of eight to ten children throughout the whole of lockdown. Now they’re back in their class of 30, so that’s 30 times more risk and they’re all in three different classes so, all of a sudden, they’ve gone from having 30 families that are accessing to now there being 90 families that are accessing, potentially, so I felt quite anxious about that when they went back.(P2)

I have been aware that I’ve been at an increased risk, and working in a school, whilst I can do everything that I can to maintain my distance and follow all of the rules, it’s difficult to make sure that the students are doing the same because they don’t have the same worries and fears about it all as I do.(T3)

My grandmother’s had both of hers [vaccinations]. She’s 86 and she didn’t want us at the house [before]…she had her second vaccination and she said, ‘Oh, give it two weeks,’ and then she was happy for us to come over and sit inside.(P11)

I think the thing is, everybody started out with amazing intentions in the first lockdown. Come back to school and we’ve all got given a million risk assessments and we’re not all being so good. Even my job share, she’s had both her vaccinations now and she doesn’t wear her mask as much.(T8)

[Covid-19 is] quite serious for some people but other people not so much. Like, children, you can’t really see symptoms, sometimes…it’s more serious for other people because they might have disabilities or have a disease where they’re terminally ill.(C8)

I like the little examples because actually I don’t think they [students] realise you’re passing it on not just to who you’ve seen but also those people that other people have seen and it’s like a massive web. I really like that green box of like an example.(T1)

What I really liked—I know I’m jumping forwards a little bit—was where you had to choose what you do, and how often you do it, and then get you to think about it again—about one thing, or two things, that you could change to reduce your risk, and everybody around you-s risk. The thing that I really struggle with the students is, it’s not just about them, it’s about everyone else around them, and they don’t get that.(T3)

I have elderly relatives who have not been vaccinated, who don’t live in the UK who are quite behind on vaccinations, but I do feel really worried and I wanna make sure that they look after themselves and know what to do to make sure—well, to try to prevent getting it.(P7)

I love my job and these children don’t have much so I wanted to come and to do the right thing but it is hard…

I felt we were just quite at risk… and some of our parents don’t tell you if they’ve been sick the night before or something so that was just… the germs or the potential to catch anything is always quite high anyway…

With parents I didn’t feel safe and when you’re asking… they put spaces around the school and told parents where they were supposed to stand but they didn’t pay much notice. I mean, it just felt like a battle trying to keep yourself safe.(T12)

I’m worried about peoples’ attitudes towards it…since the rules were relaxed people have just stopped wearing masks, stopped social distancing. I know they don’t have to anymore, but I think people have just run their course, they’re fed up with it and they don’t want to take those measures anymore, which is a shame.(T14)

They’re good ideas [from Germ Defence] because then it’s like less—there’s less chance of people catching COVID in school. And if one person in school gets it, then not everyone in school will get it.(C9)

It [Germ Defence] challenged me on the idea of wearing a face covering in my home but I think I would only do that in exceptional circumstances. It got me thinking about whether I should be wearing them when I meet with people.(P10)

And you’ve gotta still look after them haven’t you, and when my son had it we didn’t make him isolate away from the rest of us because mentally for them I think that would be really, yes, to put them in one room, yes too much.(T4)

I don’t know whether it’s feasible with a young child. … It would be very difficult for me to do it because my five-year old’s a very cuddly little boy and to tell him that he couldn’t see his mummy for seven days while she’s locked in a bedroom would be quite hard.(P1)

You may still want to be with your children when they eat because of the risk of choking, if there isn’t another adult in the house you live with.(P7)

I just don’t see that it’s realistic to keep a two-metre distance from people like your mum and dad.(C14)

The school’s not exactly built for this [social distancing]…for one thing, there’s 215 people in my year; it’s not exactly easy, and also the corridors aren’t the thickest and then they try and split them in half to make a one-way system but then the one-way system is so thin, it’s hard to walk down… because when everyone leaves the lessons at the same time, all 215 people are in one corridor so they can’t really try and keep us two metres apart otherwise everyone’s going to be really late for their lessons.(C6)

We’ve just told them they need to keep their own distance because obviously classrooms aren’t built for a two-metre gap.(T1)

I don’t think we could do that two metres apart indoors because we live in a small flat.(P7)

3.3.2. Table of Changes Analysis

It [Germ Defence] was very pragmatic about minimising touching rather than, ‘You shalt not touch,’ but if you’ve minimised, it goes back to that viral load thing really, doesn’t it? ‘You do as much as you can do, this all helps, it’s worth doing, it’s worth your inconvenience because this is how it’s going to benefit,’ and I think that’s quite good.(P9)

The first paragraph is pretty good because—I don’t know—it’s like everyone can do their bit and stuff and it makes them feel involved. It’s good that it tells everyone that you don’t know what people have at home. They could have someone who’s old. Because you never know, they might live with someone who could be at risk(C9)

We all know about it [Covid-19] of course, but a lot of students don’t really understand how wearing a mask can make a difference, and how sanitising, washing your hands can make a difference.(C13)

For your family and friends, if they’ve had the vaccination and they’re doing something that maybe they shouldn’t, you could maybe just note to them ‘maybe you shouldn’t do that, or you could do this [suggested behaviour in Germ Defence]’, and if some people think they’re invincible once they’ve had the vaccine, maybe just tip them it’s not 100% effective.(C5)

I could see this working in school, and then in a household where, for example, the parent’s primary language may not be English, actually to have children that understand this from using it at school, they may be able to communicate that to their parents, or if there is illiteracy or any other reason why the parent may not be able to take on this information themselves. Sometimes I think you can feed it through the children.(P10)

I like that it’s a simple thing that they [students] can do, which is to share it with their community, which is great. We [school staff] would, potentially, put it onto our school website, or into Twitter, or Instagram—or something like that—to share it with our students and parents as well.(T3)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Office for National Statistics. Academic Year 2020/21: Schools, Pupils and Their Characteristics. Available online: https://explore-education-statistics.service.gov.uk/find-statistics/school-pupils-and-their-characteristics (accessed on 10 September 2021).

- Poletti, P.; Tirani, M.; Cereda, D.; Trentini, F.; Guzzetta, G.; Sabatino, G.; Marziano, V.; Castrofino, A.; Grosso, F.; Del Castillo, G.; et al. Probability of symptoms and critical disease after SARS-CoV-2 infection. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2006.08471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keeling, M.J.; Tildesley, M.J.; Atkins, B.D.; Penman, B.; Southall, E.; Guyver-Fletcher, G.; Holmes, A.; McKimm, H.; Gorsich, E.E.; Hill, E.M.; et al. The impact of school reopening on the spread of COVID-19 in England. R. Soc. 2021, 376, 20200261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Department for Education. What All Schools Will Need to Do during the Coronavirus (COVID-19) Pandemic. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/actions-for-schools-during-the-coronavirus-outbreak/schools-covid-19-operational-guidance (accessed on 10 September 2021).

- Amin-Chowdhury, Z.; Bertran, M.; Kall, M.; Ireland, G.; Aiano, F.; Powell, A.; Jones, S.E.; Brent, A.; Brent, B.; Baawuah, F.; et al. Implementation of COVID-19 Preventive Measures in Primary and Secondary Schools Following Reopening of Schools in Autumn 2020; A Cross-Sectional Study of Parents’ and Teachers’ Experiences in England. MedRxiv 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenc, A.; Kesten, J.M.; Kidger, J.; Langdord, R.; Horwood, J. Reducing COVID-19 risk in schools: A qualitative examination of secondary school staff and family views and concerns in the South West of England. BMJ Public Health Emerg. Collect. 2021, 5, e000987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Staniford, L.J.; Schmidtke, K.A. A systematic review of hand-hygiene and environmental-disinfection interventions in settings with children. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michie, S.; van Stralen, M.M.; West, R. The behaviour change wheel: A new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement. Sci 2011, 6, 42–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Michie, S.; Johnston, M.; Abraham, C.; Lawton, R.; Parker, D.; Walker, A. Making psychological theory useful for implementing evidence based practice: A consensus approach. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2005, 14, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Goldberg, J.M.; Sklad, M.; Elfrink, T.R.; Schreurs, K.M.G.; Bohlmeijer, E.T.; Clarke, A.M. Effectiveness of interventions adopting a whole school approach to enhancing social and emotional development: A meta-analysis. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 2019, 34, 755–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Little, P.; Stuart, B.; Hobbs, R.; Moore, M.; Barnett, J.; Popoola, D.; Middleton, K.; Kelly, J.; Mullee, M.; Raftery, J.; et al. An internet-delivered handwashing intervention to modify influenza-like illness and respiratory infection transmission (PRIMIT): A primary care randomised trial. Lancet 2015, 24, 1631–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yardley, L.; Morrison, L.; Bradbury, K.; Muller, I. The Person-Based Approach to Intervention Development: Application to digital Health-Related Behaviour Change Interventions. J. Med. Internet Res. 2015, 17, e30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainsworth, B.; Steele, M.; Stuart, B.; Joseph, J.; Miller, S.; Morrison, L.; Little, P.; Yardley, L. Using an analysis of behaviour change to inform an effective digital intervention design: How did the PRIMIT website change hand hygiene behaviour across 8993 users? Ann. Behav. Med. 2016, 51, 423–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ainsworth, B.; Miller, S.; Denison-Day, J.; Stuart, B.; Groot, J.; Rice, C.; Bostock, J.; Hu, X.; Morton, K.; Towler, L.; et al. Current infection control behaviour patterns in the UK, and how they can be improved by “Germ Defence”, an online behavioural intervention to reduce the spread of COVID-19 in the home. MedRxi 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morton, K.; Ainsworth, B.; Miller, S.; Rice, C.; Bostock, J.; Denison-Day, J.; Towler, L.; Groot, J.; Moore, M.; Willcox, M.; et al. Adapting Behavioral Interventions for a Changing Public Health Context: A Worked Example of Implementing a Digital Intervention During a Global Pandemic Using Rapid Optimisation Methods. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 668197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CoMMinS. COVID-19 Mapping and Mitigation in Schools. Available online: https://commins.org.uk (accessed on 10 September 2021).

- Craig, P.; Dieppe, P.; Macintyre, S.; Michie, S.; Nazareth, I.; Petticrew, M. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: The new Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ 2008, 337, a1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Biezen, R.; Grando, D.; Mazza, D.; Brijnath, B. Visibility and transmission: Complexities around promoting hand hygiene in young children—A qualitative study. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chittleborough, C.R.; Nicholson, A.L.; Basker, E.; Bell, S.; Campbell, R. Factors influencing hand washing behaviour in primary schools: Process evaluation within a randomized controlled trial. Health Education Research 2012, 27, 1055–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kavitha, E.; Srikumar, R.; Muthu, G.; Sathyapriya, T. Bacteriological profile and perception on hand hygiene in school-going children. J. Lab. Physicians 2019, 11, 300–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- White, S.; Thorseth, A.H.; Dreibelbis, R.; Curtis, V. The determinants of handwashing behaviour in domestic settings: An integrative systematic review. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2020, 227, 113512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willmott, M.; Nicholson, A.; Busse, H.; MacArthur, G.J.; Brookes, S.; Campbell, R. Effectiveness of hand hygiene interventions in reducing illness absence among children in educational settings: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch. Dis. Child. 2016, 101, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutter, S.; Stones, C.; Macduff, C. Communicating Handwashing to Children, as Told by Children. Health Commun. 2020, 35, 1091–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medeiros, E.R.; Rebouças, D.G.C.; Paiva, A.C.S.; Nascimento, C.P.A.; Silva, S.Y.B.; Pinto, E.S.G. Studies evaluating of health interventions at schools: An integrative literature review. Rev. Latino Am. Enferm. 2018, 26, e3008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.S.; Duchaine, C. SARS-CoV-2 and health care worker protection in low-risk settings: A review of modes of transmission and a novel airborne model involving inhalable particles. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2020, 34, e00184-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morawska, L.; Milton, D.K. It Is Time to Address Airborne Transmission of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020, 71, 2311–2313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, H.; Zheng, X. Ventilation control for airborne transmission of human exhaled bio-aerosols in buildings. J. Thorac. Dis. 2018, 10, S2295–S2304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verberk, J.D.M.; Anthierens, S.A.; Tonkin-Crine, S.; Goossens, H.; Kinsman, J.; de Hoog, M.L.A.; Bielicki, J.A.; Bruijning-Verhagen, P.C.J.L.; Gobat, N.H. Experiences and needs of persons living with a household member infected with SARS-CoV-2: A mixed method study. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0249391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Haak, M.J.; De Jong, M.D.; Schellens, P.J. Evaluation of an informational web site: Three variants of the think-aloud method compared. Tech. Commun. 2007, 54, 58–71. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ritchie, J.; Lewis, J.; Nicholls, C.M.; Ormston, R. Qualitative Research Practice: A Guide for Social Science Students and Researchers; Sage: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Korstjens, I.; Moser, A. Series: Practical guidance to qualitative research. Part 4: Trustworthiness and publishing. Eur. J. Gen. Pract. 2018, 24, 120–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Elliott, V. Thinking about the Coding Process in Qualitative Data Analysis. Qual. Rep. 2018, 23, 2850–2861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Li, Y.; Zhang, A.L.; Wang, Y.; Molina, M.J. Identifying airborne transmission as the dominant route for the spread of COVID-19. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 14857–14863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainsworth, B.; Miller, S.; Denison-Day, J.; Stuart, B.; Groot, J.; Rice, C.; Bostock, J.; Hu, X.-Y.; Morton, K.; Towler, L.; et al. Infection Control Behavior at Home During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Observational Study of a Web-Based Behavioral Intervention (Germ Defence). J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e22197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morton, K.; Towler, L.; Groot, J.; Miller, S.; Ainsworth, B.; Denison-Day, J.; Rice, C.; Bostock, J.; Willcox, M.; Little, P.; et al. Infection control in the home: A qualitative study exploring perceptions and experiences of adhering to protective behaviours in the home during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e056161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dryhurst, S.; Schneider, C.R.; Kerr, J.; Freeman, A.L.J.; Recchia, G.; van der Bles, A.M.; Spiegelhalter, D.; van der Linden, S. Risk perceptions of COVID-19 around the world. J. Risk Res. 2020, 23, 994–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, C.R.; Dryhurst, S.; Kerr, J.; Freeman, A.L.J.; Recchia, G.; Spiegelhalter, D.; van der Linden, S. COVID-19 risk perception: A longitudinal analysis of its predictors and associations with health protective behaviours in the United Kingdom. J. Risk Res. 2021, 24, 294–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholz, U.; Freund, A.M. Determinants of protective behaviours during a nationwide lockdown in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2021, 26, 935–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenstock, I.M. The Health Belief Model and Preventive Health Behavior. Health Educ. Behav. 1974, 2, 354–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, R.W. A Protection Motivation Theory of Fear Appeals and Attitude Change. J. Psychol. 1975, 91, 93–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cori, L.; Bianchi, F.; Cadum, E.; Anthonj, C. Risk perception and COVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, H.; Sanders, C.; Prasetup, Y.; Syukron, M.; Prentice, E. Exploring the dynamic relationships between risk perception and behavior in response to the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak. Soc. Sci. Med. 2021, 285, 114267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denford, S.; Morton, K.; Horwood, J.; de Garang, R.; Yardley, L. Preventing within household transmission of Covid-19: Is the provision of accommodation to support self-isolation feasible and acceptable? BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partridge, S.R.; Redfern, J. Strategies to Engage Adolescents in Digital Health Interventions for Obesity Prevention and Management. Healthcare 2018, 6, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| User Context and Characteristics | Guiding Principle | |

|---|---|---|

| Design Objective | Key Features | |

| Minimise work required to access and engage with Germ Defence—especially for school staff. |

|

| Promote sense of collective responsibility for keeping ‘your community’ (i.e., home and family and/or school setting) safe. |

|

| Help users understand the objective of reducing rather than eliminating risk; reduce perceptions relating to measures not being worth doing if not being done perfectly. |

|

| Facilitate understanding of why each behavioural recommendation is important and how to overcome recognised barriers. |

|

| Persuade users that within-home transmission not inevitable and increase understanding of how this can be avoided. |

|

| A School/College Student | A Member of School Staff | A Parent/Guardian of a School-Aged Child | A Member of School Staff and a Parent/Guardian of a School-Aged Child | All Participants | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 10 | 12 | 11 | 4 | 37 |

| Age | |||||

| Range | 12–17 | 25–62 | 32–47 | 34–41 | 12–62 |

| Mean (SD) | 14.4 (1.7) | 39 (9.4) | 40.7 (4.6) | 38.8 (3.2) | 32.8 (12.8) |

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 6.7 (67.7%) | 2 (16.7%) | 2 (18.2%) | 6.2 (16.7%) | |

| Female | 2.2 (22.2%) | 10 (83.3%) | 9 (81.8%) | 4 (100%) | 29.8 (80.6%) |

| Other | 1.1 (11.1%) | 1 (2.8%) | |||

| Ethnicity | |||||

| English/Welsh/Scottish/Northern Irish/British | 5 (50%) | 11 (91.7%) | 10 (90.9%) | 3 (75%) | 29 (78.4%) |

| White and Asian | 1 (8.3%) | 1 (2.7%) | |||

| White and Black Caribbean | 1 (10%) | 1 (2.7%) | |||

| Other White | 1 (10%) | 1 (9.1%) | 2 (5.4%) | ||

| Indian | 1 (10%) | 1 (25%) | 2 (5.4%) | ||

| Other Asian | 2 (20%) | 2 (5.4%) | |||

| Highest Educational Level | |||||

| School | 1 (8.3%) | 1 (9.1%) | 2.1 (5.6%) | ||

| College | 2 (18.2%) | 1 (25%) | 3.1 (8.3%) | ||

| Undergraduate | 5 (41.7%) | 3 (27.3%) | 8.2 (22.2%) | ||

| Postgraduate | 6 (50%) | 5 (45.5%) | 3 (75%) | 14.4 (38.9%) | |

| Still in full-time education | 10 (100%) | 9.2 (25%) |

| Evidence | Examples | Subsequent Intervention Change |

|---|---|---|

| When I read the first paragraph I thought ‘Oh you’re joking!’ I don’t want to wear face coverings at home… I think it’s because it feels like a safe place because they’re horrible to wear and because I would think that because we don’t have people in the at-risk category in our household. (P10) It’s not always that practical… in our living arrangements. So if we, for example, have my elderly parents stay with us, space wise, I don’t think we could do that two metres apart indoors because we live in a small flat. (P7) There are some examples that you just need to quickly put one [face covering] on and it’s not really feasible. (C15) |

|

| The school’s not exactly built for this…because when everyone leaves the lessons at the same time, all 215 people are in one corridor so they can’t really try and keep us two metres apart otherwise everyone’s going to be really late for their lessons. (C6) Within school you can’t actually physically do a two-metre kind of social distancing within the actual classroom ‘cause there’s not enough space with 30 children and often you have like three or four members of staff in the room as well. (T4) It would be very difficult for me to do it because my five-year old’s a very cuddly little boy and to tell him that he couldn’t see his mummy for seven days while she’s locked in a bedroom would be quite hard. If you’ve got young children and they’re used to having you there all the time, it would be very difficult. It kind of resonates that it’s the sensible thing to do, but whether it’s feasible for all families to do, it does give people the idea of ‘if you can do it, then do it’. (P1) I almost never wash my hands before and after putting it [face covering] on, because there just wasn’t the time…in the corridor going into the classroom, not all the classrooms have sinks anyway. (C15) We don’t give the students the opportunity to wash their hands regularly within school—they come into the classroom, they sanitise their hands and then, when they leave the classroom, they sanitise their hands, but they don’t wash them as such. (T3) So, the fresh air thing we are doing that but obviously in the winter that was a bit of a tricky situation because we were told we obviously had to shut the windows because it was absolutely freezing. So, that was a bit tricky. (T8) |

|

| I think they need to know why it’s important for them to have a vaccination. (T3) It might just confuse them [children] thinking, ’Why am I reading a vaccination page?’ Or, ’Am I going to have a vaccination now?’ Or, ’Why am I reading it because I don’t think I get one.’ Sort of thing, so it’s a waste of time. (P1) I mean children maybe who were younger than me might not really find it that helpful, but people my age and definitely older people will find it really helpful. (C2) |

|

| On the ‘what would you do in the future’ [page] I think maybe you could simplify the way it’s explaining what you have to do for that bit? Because I was confused in what I actually have to do. (C1) I thought, why are they asking me it again? And then the second one was, now you’ve done this, what will you do better? (T10) |

|

| A few more pictures, maybe like a bit more colour, but it’s relatively informative and yeah, just to be made more to a child’s level of how they would speak rather than adults (P6) Sometimes when things are too long, people will just not read it and just skim past it, but if it’s like a short sentence in a bright green box, you’re more likely to just quickly read it (C12) I didn’t know what that [not applicable] means so maybe some other kids my age might not know what it means, or even older (C7) |

|

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Treneman-Evans, G.; Ali, B.; Denison-Day, J.; Clegg, T.; Yardley, L.; Denford, S.; Essery, R. The Rapid Adaptation and Optimisation of a Digital Behaviour-Change Intervention to Reduce the Spread of COVID-19 in Schools. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6731. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19116731

Treneman-Evans G, Ali B, Denison-Day J, Clegg T, Yardley L, Denford S, Essery R. The Rapid Adaptation and Optimisation of a Digital Behaviour-Change Intervention to Reduce the Spread of COVID-19 in Schools. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(11):6731. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19116731

Chicago/Turabian StyleTreneman-Evans, Georgia, Becky Ali, James Denison-Day, Tara Clegg, Lucy Yardley, Sarah Denford, and Rosie Essery. 2022. "The Rapid Adaptation and Optimisation of a Digital Behaviour-Change Intervention to Reduce the Spread of COVID-19 in Schools" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 11: 6731. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19116731

APA StyleTreneman-Evans, G., Ali, B., Denison-Day, J., Clegg, T., Yardley, L., Denford, S., & Essery, R. (2022). The Rapid Adaptation and Optimisation of a Digital Behaviour-Change Intervention to Reduce the Spread of COVID-19 in Schools. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(11), 6731. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19116731