Evaluation of an Electronic Medical Record Module for Nursing Documentation in Paediatric Palliative Care: Involvement of Nurses with a Think-Aloud Approach

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants and Recruitment

2.3. Data collection and Testing Procedure

- (1)

- Remote testing: During remote sessions, participants shared their screen with evaluators using the software Zoom. Relevant documents were sent to participants in advance by email.

- (2)

- Face-to-face testing: Face-to-face testing sessions were conducted in a regular office close to the PPC unit, with the evaluators using a standardized software and hardware setup. The hardware setup consisted of a computer with a mirrored screen so that the researchers could observe the use of the modules.

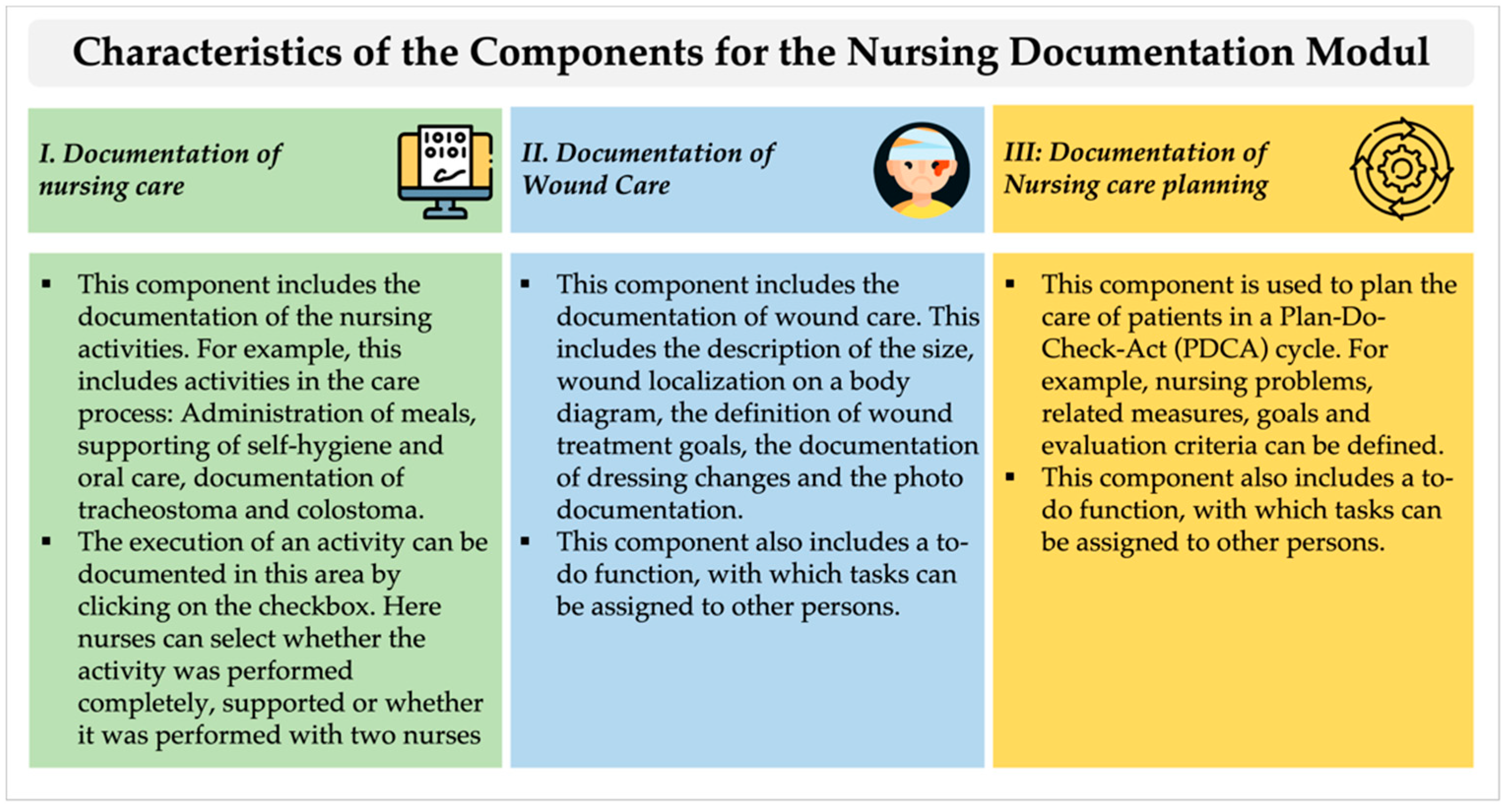

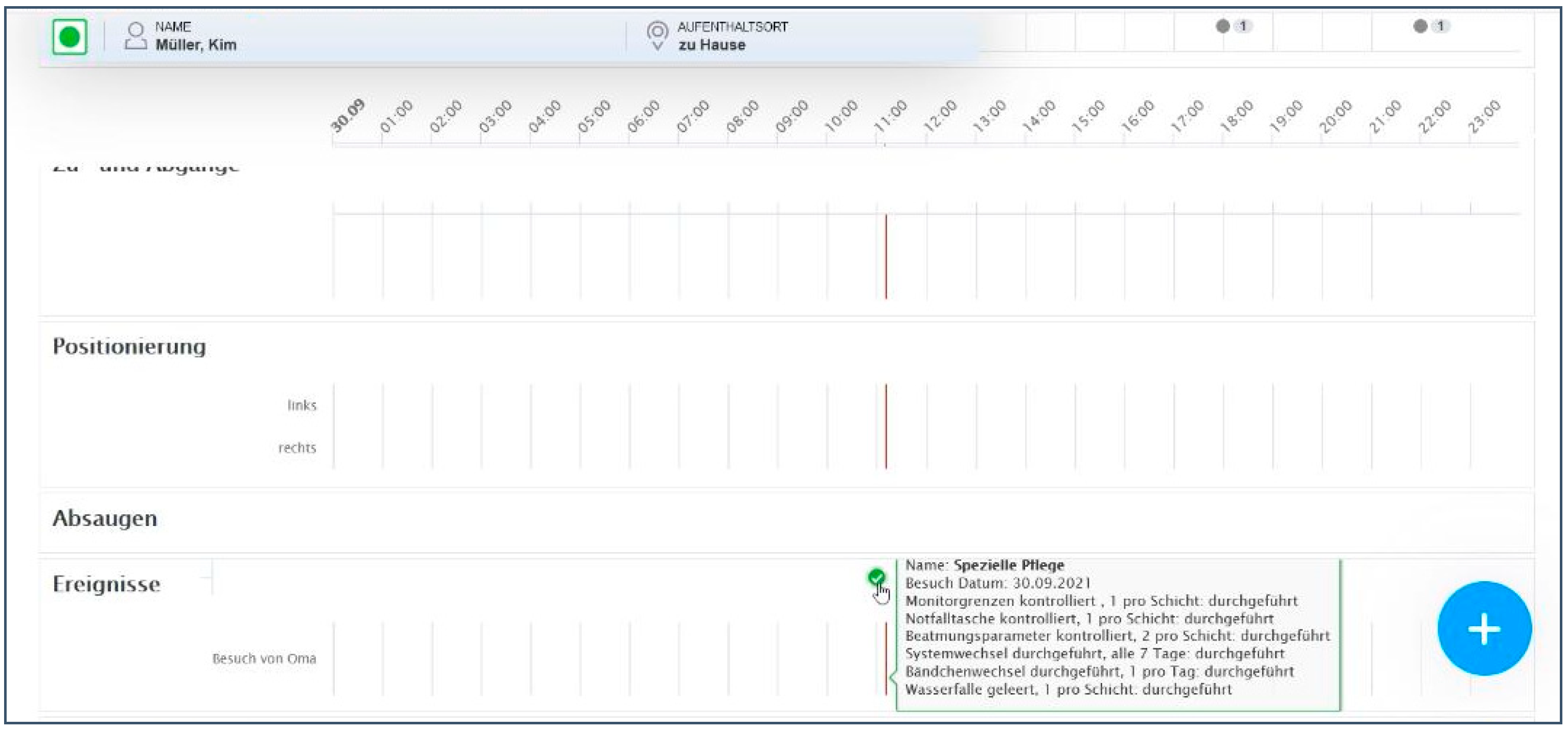

2.4. Module for Nursing Documentation

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Performance Expectancies

- (a) Self-explanatory and easy-to-use

“Well, in itself I think it is quite good and also as detailed as it is now described here, always quite self-explanatory. But I think it is still quite difficult at first, because it is simply a change, and at the beginning, we will just click on different things, I think, to look for where it is really to be found in the end or where I can enter something exactly again.”(Nurse_01_#01:12:15#)

- (b) Support and time reduction through checkboxes

“But I think if you really have such patients [with decubiti], or we just have a patient with, for example, epidermolysis bullosa, where you also have to change the dressing every two days, it is quite practical if you just have to mark a [predefined] list with a cross [the checkbox] concerning what the wound is cleaned with and what it is fixed with and what kind of materials are used. Because otherwise, it is a lot of work to keep lists and write things down.”(Nurse_06_#00:29:23#)

- (c) Usefulness of the to-do function

“So, I think that is really good. And that I can then perhaps also select times, so, I would like to select that a physician is coming to the next care. Because the doctors would then probably also see that it is a to-do for them. And I do not have to run after them and say, ‘Remember, you have to come to change the dressings or something else’. I think that is definitely very, very good.”(Nurse_01_#00:51:43#)

- (d) Adding context-specific information with free text fields

- Nurse:

- “Can I add additional information somewhere, so that everyone [colleagues] also knows, aha, the skin must be creamed with the cream XY and not with wound protection cream?”.

- Interviewer:

- “Is it not intended yet, but you would just wish that one could insert information here as free text?”.

- B:

- “Yes, for example. We often write additional information in the [paper-based] nursing documentation, and that corresponds a bit to the care planning here. That you then see: Aha, we are now using cream XY or water only. I would miss that here now.” (Nurse_09_#00:10:51#).

- (e) Restoration of problems in nursing care planning from past hospitalizations

“Yes, I would like that. So, if the nursing problems are transferred to the archive, if the patient was already here in May [in the PPC unit], I say, and the patient comes back now and I can actually take over half of the problems one to one, because it has not changed. For example, if the patient still tends towards constipation or still has secretion problems, you still do the same thing, that you can quite simply just click, and it [the software] takes over automatically.”(Nurse_08_#01:19:08#)

- (f) Usefulness of the body scheme for wound documentation

“Oh yes, it works. Exactly, I think it is good that you have such a scheme, such a body scheme. Because sometimes you cannot describe it as well as you might have seen it, i.e., where the spot is. So, I think that is great. Exactly, here I can enter everything with five centimetres, two centimetres, whatever.”(Nurse_08_#00:32:25-7#)

3.2. Effort Expectancies

- (a) Fragmentation of the display

“What I find a bit impractical when I scroll down is that you then no longer see the headline: then have to scroll up again and then I see which nursing activity I have to click on. And where did I end up now?”(Nurse_08_#00:08:29#)

- (b) Visibility of functions

“If I click on that now? Can you do that? No. […] But you cannot click on that now? […] Well, this is all here not to click on, no. I find that irritating now, because I do not know how to do document the nursing activities.”(Nurse_03_#00:04:05#)

- (c) Use of familiar nursing terminology

- Nurse:

- “Okay, in the nursing report, in the free text, I have to document a nursing report. It is up there now. Just looking. […]. Cannot add it here, can I? Oh, maybe in the filed ‘comments’”.

- Interviewer:

- “But I could add some free text there now. But you would not have recognized it as such now, so to speak?”.

- Nurse:

- “I would not have recognized it [the field ‘comments’ for ‘nursing report’]”.

- Interviewer:

- “What would help you recognize that sooner?”.

- Nurse:

- “I think that would really have to be called nursing report too.” (Nurse_03_#00:09:38#).

- (d) Confusing mouseover field

“I find that [the mouseover field] totally confusing here. If I click on it now, it shows me what I have done [which activities were documented]. I find that super confusing. I wouldnot be able to cope with it, I would give up again.”(Nurse_09_#00:32:08#)

3.3. Facilitating Conditions

- (a) Insufficient number of computer workstations

“That we do not have enough workstations with computers. That one wants it, the next and there, that there is friction, exactly. Yes, that would be one of the biggest fears I have.”(Nurse_11_#00:46:12#)

- (b) Fears concerning technical problems

“That it does not work and I cannot access the electronic medical record. That would give me a stomach-ache, that I just could not get to the things that were important for the patient right now. That I do not know, okay, now I do no know, the patient is cramping, I need a medication now, but I do not know what I can give because I cannot access the electronic medical record. Or what if the internet time is not working or the connection is just too slow.”(Nurse_09_#01:30:08#)

- (c) Near-bedside documentation

“But otherwise with the implementation [of the EMR], is it meant that we then have it [the EMR] on a tablet, so we could take it with us [to the patient’s room]? Because I think that if you take it with you, you can do it directly after you have done something [e.g., nursing activities] with the child. Or whether you must go back [to a workstation] again first.”(Nurse_08_#00:56:09#)

- (d) Efficiency and readability

“I am hoping that once you are well into it [the digital documentation] and you know where to enter what, that it will not take as much time as the handwritten documentation. That, and maybe also that you do not have to write anymore so much [by hand]. That it is all easy to read, above all, even the doctor’s handwriting. And that it is partly also clearly shorter, more compact […].”(Nurse_03_#01:00:15#)

- (e) Increased clarity of to-do lists and the assurance that things are not forgotten

“In the long run, I hope that it will make my work easier […]. That it is clear what you have to do. That the to-dos pop up in such a way that I also forget fewer things in the end or simply that fewer things get lost. Maybe also a little bit that things that are sometimes considered unnecessary in certain situations, that they are then extra penetratingly annoying with the to-do pop-ups so that you just do it and you do not forget it anymore.”(Nurse_01_#01:00:15#)

- (f) Changeover to digital documentation difficult for older users

“I think that [change to] digital documentation will be more difficult for some older colleagues, but I think that if you put your mind to it a bit and you get used to it, they would be able to do it quite well, and I have to be prepared for it.”(Nurse_05_#00:46:17#)

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Acronyms

| PPC | Paediatric palliative care |

| UTAUT | Unified theory of acceptance and use of technology |

| EMRs | Electronic medical records |

| CTA | Concurrent thinking aloud |

| ISPC | Information-system palliative care |

| NLCS | Near live clinical simulations |

Appendix B. Interview Guide

- –

- Can you describe to me in your own words the problem you are having right now?

- –

- What would you expect here?

- –

- What would you have expected here (instead)?

- –

- How would you solve the problem?

- –

- What would you like to see happen?

Appendix C. Guide for the Qualitative Interview

- How would you describe your overall impression of the application?

- Nursing documentation in general: What else would you like to see in the EMR regarding nursing documentation in the context of PPC?

- (a)

- Is there anything that you felt was missing?

- (b)

- Is there anything that you did not feel was necessary?

- (c)

- What other adjustments would you like to see?

- If not yet named: How did you find the service?

- (a)

- Is there anything that you liked about it?

- (b)

- Is there anything that you did not like about it?

- Can you describe in your own words how you would rate the clarity of the new modules: Was the content easy/quick to find?

- If you imagine that the EMR/digital documentation were introduced in practice for your unit:

- (a)

- Can you describe for me in your own words what your fears would be if there was a switch from analogue to digital documentation?

- (b)

- Can you describe to me in your own words what benefits you would hope to gain if there were a switch from analogue to digital documentation?

- How did you feel about the test situation?

- (a)

- ... especially the thinking out loud and the general situation?

References

- Hoell, J.I.; Weber, H.; Warfsmann, J.; Trocan, L.; Gagnon, G.; Danneberg, M.; Balzer, S.; Keller, T.; Janßen, G.; Kuhlen, M. Facing the Large Variety of Life-Limiting Conditions in Children. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2019, 178, 1893–1902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoell, J.I.; Warfsmann, J.; Distelmaier, F.; Borkhardt, A.; Janßen, G.; Kuhlen, M. Challenges of Palliative Care in Children with Inborn Metabolic Diseases. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2018, 13, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Côté, A.-J.; Payot, A.; Gaucher, N. Paediatric Palliative Care in Practice: Perspectives between Acute and Long-Term Healthcare Teams. Acta Paediatr. 2019, 109, 613–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Connor, S.R.; Downing, J.; Marston, J. Estimating the Global Need for Palliative Care for Children: A Cross-Sectional Analysis. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2016, 53, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trowbridge, A.; Stewart, M.T.; Rhee, E.; Hwang, J.M. Providing Palliative Care in Rare Pediatric Diseases: A Case Series of Three Children with Congenital Disorder of Glycosylation. J. Palliat. Med. 2017, 20, 104–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thrane, S.E.; Maurer, S.H.; Cohen, S.M.; May, C.; Sereika, S.M. Pediatric Palliative Care: A Five-Year Retrospective Chart Review Study. J. Palliat. Med. 2017, 20, 1104–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bender, H.U.; Riester, M.B.; Borasio, G.D.; Führer, M. “Let’s Bring Her Home First.” Patient Characteristics and Place of Death in Specialized Pediatric Palliative Home Care. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2017, 54, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Amarri, S.; Ottaviani, A.; Campagna, A.; De Panfilis, L. Children with Medical Complexity and Paediatric Palliative Care: A Retrospective Cross-Sectional Survey of Prevalence and Needs. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2021, 47, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolte-Buchholtz, S.; Zernikow, B.; Wager, J. Pediatric Patients Receiving Specialized Palliative Home Care According to German Law: A Prospective Multicenter Cohort Study. Children 2018, 5, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lin, S.-C.; Huang, M.-C.; Yasmara, D.; Wuu, H.-L. Impact of Palliative Care on End-of-Life care and Place of Death in Children, Adolescents, and Young Adults with Life-Limiting Conditions: A Systematic Review. Palliat. Support. Care 2021, 19, 488–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, D.Z.; McAllister, J.W.; Rossignol, L.; Turchi, R.M.; Stille, C.J. Care Coordination for Children with Medical Complexity: Whose Care Is It, Anyway? Pediatrics 2018, 141, S224–S232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Abebe, E.; Scanlon, M.C.; Chen, H.; Yu, D. Complexity of Documentation Needs for Children with Medical Complexity: Implications for Hospital Providers. Hosp. Pediatr. 2020, 10, 00. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Donnell, H.C.; Suresh, S.; Webber, E.C.; Alexander, G.M.; Chung, S.L.; Hamling, A.M.; Kirkendall, E.S.; Mann, A.M.; Sadeghian, R.; Shelov, E.; et al. Electronic Documentation in Pediatrics: The Rationale and Functionality Requirements. Pediatrics 2020, 146, 00. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, C.H.; Eghdam, A.; Davoody, N.; Wright, G.; Flowerday, S.; Koch, S. Effects of Electronic Health Record Implementation and Barriers to Adoption and Use: A Scoping Review and Qualitative Analysis of the Content. Life 2020, 10, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathert, C.; Porter, T.H.; Mittler, J.N.; Fleig-Palmer, M. Seven Years after Meaningful Use: Physicians’ and Nurses’ Experiences with Electronic Health Records. Healthc. Manag. Rev. 2019, 44, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campanella, P.; Lovato, E.; Marone, C.; Fallacara, L.; Mancuso, A.; Ricciardi, W.; Specchia, M.L. The Impact of Electronic Health Records on Healthcare Quality: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Eur. J. Public Health 2015, 26, 60–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Akard, T.F.; Hendricks-Ferguson, V.L.; Gilmer, M.J. Pediatric Palliative Care Nursing. Ann. Palliat. Med. 2019, 8, S39–S48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaihlanen, A.-M.; Gluschkoff, K.; Hyppönen, H.; Kaipio, J.; Puttonen, S.; Vehko, T.; Saranto, K.; Karhe, L.; Heponiemi, T. The Associations of Electronic Health Record Usability and User Age with Stress and Cognitive Failures among Finnish Registered Nurses: Cross-Sectional Study. JMIR Med. Inform. 2020, 8, e23623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bøgeskov, B.O.; Grimshaw-Aagaard, S.L.S. Essential Task or Meaningless Burden? Nurses’ Perceptions of the Value of Documentation. Nord. J. Nurs. Res. 2018, 39, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu Raddaha, A.H.; Obeidat, A.; Al Awaisi, H.; Hayudini, J. Opinions, Perceptions and Attitudes toward an Electronic Health Record System among Practicing Nurses. J. Nurs. Educ. Pract. 2017, 8, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jedwab, R.; Hutchinson, A.; Manias, E.; Calvo, R.; Dobroff, N.; Glozier, N.; Redley, B. Nurse Motivation, Engagement and Well-Being before an Electronic Medical Record System Implementation: A Mixed Methods Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gephart, S.M.; Carrington, J.M.; Finley, B.A. A Systematic Review of Nurses’ Experiences with Unintended Consequences When Using the Electronic Health Record. Nurs. Adm. Q. 2015, 39, 345–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powers, E.M.; Shiffman, R.N.; Melnick, E.R.; Hickner, A.; Sharifi, M. Efficacy and Unintended Consequences of Hard-Stop Alerts in Electronic Health Record Systems: A Systematic Review. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2018, 25, 1556–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Snowden, A.; Kolb, H. Two Years of Unintended Consequences: Introducing an Electronic Health Record System in a Hospice in Scotland. J. Clin. Nurs. 2017, 26, 1414–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Middleton, B.; Bloomrosen, M.; Dente, M.A.; Hashmat, B.; Koppel, R.; Overhage, J.; Payne, T.H.; Rosenbloom, S.T.; Weaver, C.; Zhang, J. Enhancing Patient Safety and Quality of Care by Improving the Usability of Electronic Health Record Systems: Recommendations from AMIA. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2013, 20, e2–e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinnunen, U.-M.; Heponiemi, T.; Rajalahti, E.; Ahonen, O.; Korhonen, T.; Hyppönen, H. Factors Related to Health Informatics Competencies for Nurses—Results of a National Electronic Health Record Survey. CIN Comput. Inform. Nurs. 2019, 37, 420–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salameh, B.; Eddy, L.L.; Batran, A.; Hijaz, A.; Jaser, S. Nurses’ Attitudes toward the Use of an Electronic Health Information System in a Developing Country. SAGE Open Nurs. 2019, 5, 2377960819843711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melnick, E.R.; West, C.P.; Nath, B.; Cipriano, P.F.; Peterson, C.; Satele, D.V.; Shanafelt, T.; Dyrbye, L.N. The Association between Perceived Electronic Health Record Usability and Professional Burnout among US Nurses. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2021, 28, 1632–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khairat, S.; Xi, L.; Liu, S.; Shrestha, S.; Austin, C. Understanding the Association between Electronic Health Record Satisfaction and the Well-Being of Nurses: Survey Study. JMIR Nurs. 2020, 3, e13996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, D.A.; Haskell, J.; Cooper, E.; Crouse, N.; Gardner, R. Estimating the Association between Burnout and Electronic Health Record-Related Stress among Advanced Practice Registered Nurses. Appl. Nurs. Res. 2018, 43, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khairat, S.; Coleman, G.C.; Ottmar, P.; Jayachander, D.I.; Bice, T.; Carson, S.S. Association of Electronic Health Record Use with Physician Fatigue and Efficiency. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e207385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazur, L.M.; Mosaly, P.R.; Moore, C.; Marks, L. Association of the Usability of Electronic Health Records with Cognitive Workload and Performance Levels among Physicians. JAMA Netw. Open 2019, 2, e191709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, G.; Wilding, H.; Gray, K.; Castle, D. Participatory Methods to Engage Health Service Users in the Development of Electronic Health Resources: Systematic Review. J. Particip. Med. 2019, 11, e11474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Vandekerckhove, P.; de Mul, M.; Bramer, W.M.; de Bont, A.A. Generative Participatory Design Methodology to Develop Electronic Health Interventions: Systematic Literature Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e13780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andargoli, A.E.; Scheepers, H.; Rajendran, D.; Sohal, A. Health Information Systems Evaluation Frameworks: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2017, 97, 195–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanderhook, S.; Abraham, J. Unintended Consequences of EHR Systems: A Narrative Review. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Human Factors and Ergonomics in Health Care, New Orleans, LA, USA, 5–8 March 2017; SAGE Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2017; Volume 6, pp. 218–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wisner, K.; Lyndon, A.; Chesla, C.A. The Electronic Health Record’s Impact on Nurses’ Cognitive Work: An Integrative Review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2019, 94, 74–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Følstad, A. Users’ Design Feedback in Usability Evaluation: A Literature Review. Human-Centric Comput. Inf. Sci. 2017, 7, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zurynski, Y.; Ellis, L.A.; Tong, H.L.; Laranjo, L.; Clay-Williams, R.; Testa, L.; Meulenbroeks, I.; Turton, C.; Sara, G. Implementation of Electronic Medical Records in Mental Health Settings: Scoping Review. JMIR Ment. Health 2021, 8, e30564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadoughi, F.; Khodaveisi, T.; Ahmadi, H. The Used Theories for the Adoption of Electronic Health Record: A Systematic Literature Review. Health Technol. 2018, 9, 383–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Morris, M.G.; Davis, G.B.; Davis, F.D. User Acceptance of Information Technology: Toward a Unified View. MIS Q. 2003, 27, 425–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dabliz, R.; Poon, S.K.; Ritchie, A.; Burke, R.; Penm, J. Usability Evaluation of an Integrated Electronic Medication Management System Implemented in an Oncology Setting Using the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2021, 21, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiferaw, K.B.; Mehari, E.A. Modeling Predictors of Acceptance and Use of Electronic Medical Record System in a Resource Limited Setting: Using Modified UTAUT Model. Inform. Med. Unlocked 2019, 17, 100182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, D.; Kernebeck, S.; Busse, T.; Ehlers, J.; Wager, J.; Zernikow, B.; Dreier, L. Electronic Health Records in Specialized Pediatric Palliative Care: A Qualitative Needs Assessment among Professionals Experienced and Inexperienced in Electronic Documentation. Children 2021, 8, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kernebeck, S.; Busse, T.S.; Jux, C.; Meyer, D.; Dreier, L.A.; Zenz, D.; Zernikow, B.; Ehlers, J.P. Participatory Design of an Electronic Medical Record for Paediatric Palliative Care: A Think-Aloud Study with Nurses and Physicians. Children 2021, 8, 695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, M.; Lin, J.; Chung, C.; Truong, K.N. Concurrent Think-Aloud Verbalizations and Usability Problems. ACM Trans. Comput. Interact. 2019, 26, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhadreti, O. Comparing Two Methods of Usability Testing in Saudi Arabia: Concurrent Think-Aloud vs. Co-Discovery. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2020, 37, 118–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roman, L.C.; Ancker, J.S.; Johnson, S.B.; Senathirajah, Y. Navigation in the Electronic Health Record: A Review of the Safety and Usability Literature. J. Biomed. Inform. 2017, 67, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, S.; Edwards, H.M.; Zhao, T. Exploring Think-Alouds in Usability Testing: An International Survey. IEEE Trans. Dependable Secur. Comput. 2012, 55, 2–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busse, T.S.; Jux, C.; Kernebeck, S.; Dreier, L.A.; Meyer, D.; Zenz, D.; Zernikow, B.; Ehlers, J.P. Participatory Design of an Electronic Cross-Facility Health Record (ECHR) System for Pediatric Palliative Care: A Think-Aloud Study. Children 2021, 8, 839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russ, A.L.; Saleem, J.J. Ten factors to consider when developing usability scenarios and tasks for health information technology. J. Biomed. Inform. 2018, 78, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dresing, T.; Pehl, T. Praxisbuch Interview, Transkription & Analyse. Anleitungen und Regelsysteme für Qualitativ Forschende; Eigenverlag: Marburg, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- O’Malley, A.S.; Draper, K.; Gourevitch, R.; Cross, D.A.; Scholle, S.H. Electronic Health Records and Support for Primary Care Teamwork. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2015, 22, 426–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Arndt, B.G.; Beasley, J.W.; Watkinson, M.D.; Temte, J.L.; Tuan, W.-J.; Sinsky, C.A.; Gilchrist, V.J. Tethered to the EHR: Primary Care Physician Workload Assessment Using EHR Event Log Data and Time-Motion Observations. Ann. Fam. Med. 2017, 15, 419–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, D.R.; Giardina, T.D.; Satterly, T.; Sittig, D.F.; Singh, H. An Exploration of Barriers, Facilitators, and Suggestions for Improving Electronic Health Record Inbox-Related Usability. JAMA Netw. Open 2019, 2, e1912638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Tai-Seale, M.; Dillon, E.C.; Yang, Y.; Nordgren, R.; Steinberg, R.L.; Nauenberg, T.; Lee, T.C.; Meehan, A.; Li, J.; Chan, A.S.; et al. Physicians’ Well-Being Linked to In-Basket Messages Generated by Algorithms In Electronic Health Records. Health Aff. 2019, 38, 1073–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farokhzadian, J.; Khajouei, R.; Hasman, A.; Ahmadian, L. Nurses’ Experiences and Viewpoints about the Benefits of Adopting Information Technology in Health Care: A Qualitative Study in Iran. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2020, 20, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kossman, S.P.; Scheidenhelm, S.L. Nurses’ Perceptions of the Impact of Electronic Health Records on Work and Patient Outcomes. CIN Comput. Inform. Nurs. 2008, 26, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nguyen, L.; Bellucci, E.; Nguyen, L.T. Electronic Health Records Implementation: An Evaluation of Information System Impact and Contingency Factors. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2014, 83, 779–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollack, A.H.; Pratt, W. Association of Health Record Visualizations with Physicians’ Cognitive Load When Prioritizing Hospitalized Patients. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e1919301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- De Leeuw, J.A.; Woltjer, H.; Kool, R.B. Identification of Factors Influencing the Adoption of Health Information Technology by Nurses Who Are Digitally Lagging: In-Depth Interview Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e15630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiebe, N.; Varela, L.O.; Niven, D.J.; Ronksley, P.E.; Iragorri, N.; Quan, H. Evaluation of Interventions to Improve Inpatient Hospital Documentation within Electronic Health Records: A Systematic Review. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2019, 26, 1389–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaaf, J.; Sedlmayr, M.; Sedlmayr, B.; Prokosch, H.-U.; Storf, H. Evaluation of a Clinical Decision Support System for Rare Diseases: A Qualitative Study. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2021, 21, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alroobaea, R.; Mayhew, P.J. How Many Participants Are Really Enough for Usability Studies? In Proceedings of the Science and Information Conference, London, UK, 27–29 August 2014; pp. 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiyegbusi, O.L. Key methodological considerations for usability testing of electronic patient-reported outcome (ePRO) systems. Qual. Life Res. 2020, 29, 325–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Peute, L.W.; de Keizer, N.F.; Jaspers, M.W. The Value of Retrospective and Concurrent Think Aloud in Formative Usability Testing of a Physician Data Query Tool. J. Biomed. Inform. 2015, 55, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Prokop, M.; Pilař, L.; Tichá, I. Impact of Think-Aloud on Eye-Tracking: A Comparison of Concurrent and Retrospective Think-Aloud for Research on Decision-Making in the Game Environment. Sensors 2020, 20, 2750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, S.; Mishuris, R.; O’Connell, A.; Feldstein, D.; Hess, R.; Smith, P.; McCullagh, L.; McGinn, T.; Mann, D. “Think Aloud” and “Near Live” Usability Testing of Two Complex Clinical Decision Support Tools. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2017, 106, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergen, N.; Labonté, R. “Everything Is Perfect, and We Have No Problems”: Detecting and Limiting Social Desirability Bias in Qualitative Research. Qual. Health Res. 2019, 30, 783–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansler, J.P. Challenges in User-Driven Optimization of EHR: A Case Study of a Large Epic Implementation in Denmark. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2021, 148, 104394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, M.C.; Hills, R.; Demiris, G. Understanding Optimisation Processes of Electronic Health Records (EHRs) in Select Leading Hospitals: A Qualitative Study. BMJ Healthc. Inform. 2018, 25, 109–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Skela-Savič, B.; Lobe, B. Differences in Beliefs on and Implementation of Evidence-Based Practice According to Type of Health Care Institution—A National Cross-Sectional Study among Slovenian Nurses. J. Nurs. Manag. 2020, 29, 971–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| UTAUT Determinant | Definition |

|---|---|

| Performance expectancy | “The degree to which an individual believes that using the system will help him or her to attain gains in job performance,” which encompasses mainly the functionalities of a technology. |

| Effort expectancy | “The degree of ease associated with the use of the system,” which basically includes the dimension of perceived usability and complexity of use. |

| Social influence | “The degree to which an individual perceives that important others believe he or she should use the new system”. |

| Facilitating conditions | “The degree to which an individual believes that an organizational and technical infrastructure exists to support use of the system”. |

| Characteristic | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Female | 11 |

| Male | 0 |

| Age in years (Mean) | 36 1 |

| Profession | |

| Nurse | 11 1 |

| Years of PPC experience | |

| 0–9 | 3 1 |

| 10–20 | 4 1 |

| >20 | 2 1 |

| Years of experience in current position | |

| 0–9 | 4 1 |

| 10–20 | 4 1 |

| >20 | 1 1 |

| Experience in professional use of EMR | 0 1 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kernebeck, S.; Busse, T.S.; Jux, C.; Dreier, L.A.; Meyer, D.; Zenz, D.; Zernikow, B.; Ehlers, J.P. Evaluation of an Electronic Medical Record Module for Nursing Documentation in Paediatric Palliative Care: Involvement of Nurses with a Think-Aloud Approach. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3637. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19063637

Kernebeck S, Busse TS, Jux C, Dreier LA, Meyer D, Zenz D, Zernikow B, Ehlers JP. Evaluation of an Electronic Medical Record Module for Nursing Documentation in Paediatric Palliative Care: Involvement of Nurses with a Think-Aloud Approach. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(6):3637. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19063637

Chicago/Turabian StyleKernebeck, Sven, Theresa Sophie Busse, Chantal Jux, Larissa Alice Dreier, Dorothee Meyer, Daniel Zenz, Boris Zernikow, and Jan Peter Ehlers. 2022. "Evaluation of an Electronic Medical Record Module for Nursing Documentation in Paediatric Palliative Care: Involvement of Nurses with a Think-Aloud Approach" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 6: 3637. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19063637

APA StyleKernebeck, S., Busse, T. S., Jux, C., Dreier, L. A., Meyer, D., Zenz, D., Zernikow, B., & Ehlers, J. P. (2022). Evaluation of an Electronic Medical Record Module for Nursing Documentation in Paediatric Palliative Care: Involvement of Nurses with a Think-Aloud Approach. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(6), 3637. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19063637