Abstract

Hyperglycemia and pulmonary hypertension (PH) share common pathological pathways that lead to vascular dysfunction and resultant cardiovascular complications. These shared pathologic pathways involve endothelial dysfunction, inflammation, oxidative stress, and hormonal imbalances. Individuals with hyperglycemia or pulmonary hypertension also possess shared clinical factors that contribute to increased morbidity from both diseases. This review aims to explore the relationship between PH and hyperglycemia, highlighting the mechanisms underlying their association and discussing the clinical implications. Understanding these common pathologic and clinical factors will enable early detection for those at-risk for complications from both diseases, paving the way for improved research and targeted therapeutics.

1. Introduction

Pulmonary hypertension is a progressive vasculopathy involving the expanse of the pulmonary vascular bed characterized by endothelial cell dysfunction and smooth muscle cell proliferative hypertrophy among its various defining histopathologic attributes [1]. The pathologically increased pulmonary vascular resistance that occurs secondary to this vasculopathy diminishes pulmonary blood flow and gas exchange, and leads to progressive right heart failure and associated increased mortality. Pulmonary hypertension is classified into five separate groups, broadly separated by associated and causative clinical characteristics [2,3]. While alterations in metabolism and glycemic homeostasis have been primarily described in human and animal models of pulmonary arterial hypertension (Group 1—PAH) [4,5,6,7], metabolic alterations can exist across other PH groups [6]. Altered glucose metabolism is associated with cardiovascular and chronic lung diseases that are implicated in the development of other types of pulmonary hypertension (Groups 2, and 3, respectively). Metabolic syndrome and pulmonary hypertension, though traditionally viewed as distinct entities, exhibit compelling associations that extend beyond shared comorbidity, including shared pathophysiological mechanisms, clinical implications with synergistic outcomes, and potential therapeutic interventions. Pulmonary hypertension (PH) and insulin resistance reveal overlapping molecular mechanisms, suggesting an interplay between these diseases. Specific signaling cascades, including dysregulation of the PI3K/Akt pathway, inflammation, and endothelial dysfunction, emerge as common factors, suggesting a potential bidirectional influence between insulin resistance and PH. Chronic inflammation, oxidative stress, hormonal factors and endothelial dysfunction—common features in metabolic disorders—are also implicated in the pathogenesis of pulmonary hypertension [4,5,6]. Epidemiological and clinical studies establish a strong correlation between metabolic syndrome components (obesity, dyslipidemia, insulin resistance, and hypertension) and the incidence and severity of pulmonary hypertension [8]. Research suggests patients with pulmonary hypertension are at a higher risk for complications from the insulin resistance and concomitant impaired glucose metabolism and insulin resistance can exacerbate the already compromised cardiovascular function in pulmonary hypertension, leading to an increased risk of adverse outcomes such as progressive vascular remodeling, right heart failure and overall decreased functional capacity [8]. Understanding the interplay between pulmonary hypertension and the insulin resistance that characterizes metabolic syndrome is crucial for comprehensive patient care and may pave the way for targeted interventions to improve clinical and quality of life outcomes.

2. Pathophysiology of Pulmonary Hypertension

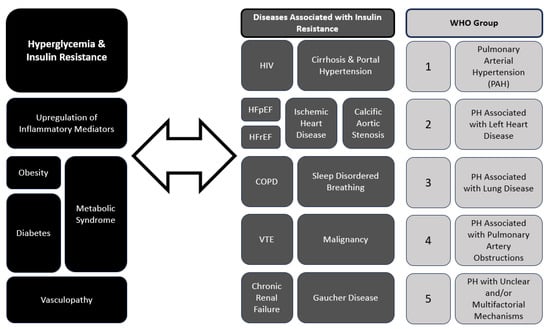

Pulmonary hypertension can arise from various etiologies, including pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH), pulmonary hypertension due to left heart disease (PH-LHD), pulmonary hypertension associated with chronic lung disease, and chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH). Current guidelines describe five groups of PH designated by the World Health Organization (WHO Groups 1–5) with shared pathophysiological and clinical features (See Figure 1, WHO groups) [1,3,9,10]. Within the pulmonary vascular bed, all compartments, namely PAs, arterioles, capillaries, veins and venules, are involved in the remodeling process to different degrees, depending on the underlying associated systemic conditions and clinical subgroup [1,10]. In all of groups of PH, the underlying vascular remodeling leads to shared hemodynamic alterations of increased pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) and resultant increased right ventricular pressure overload and heart failure. In PAH (Group 1), vascular remodeling is characterized by endothelial dysfunction, and vasoconstriction contributing to elevated pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) [10]. Similarly, in CTEPH (Group 4), parallel processes of (i.) trans endothelial migration, (ii.) heightened expression of endothelial adhesion molecules, and (iii.) dysfunctional endothelial tissue are upregulated with an overall influx of inflammatory cells that characterize chronic venous thromboembolism leading to increased PVR [9]. The pathophysiology of PH-LHD (Group 2) involves left ventricular dysfunction and elevated left-sided filling pressures, which subsequently lead to chronically elevated pulmonary vascular bed pressures and remodeling. Chronic lung disease-associated PH (Group 3) is at least in part due to chronic hypoxemia or in the case of obstructive sleep apnea chronic intermittent nocturnal hypoxemia, leading to unopposed hypoxia-induced vasoconstriction and increased PVR. In all PH clinical groups, the concomitant presence of PH worsens morbidity of the underlying associated conditions and leads increased mortality, usually as a complication of right-sided heart failure [1,2].

Figure 1.

Interplay between Hyperglycemia, Insulin Resistance and Pulmonary Hypertension (PH). HIV—human immunodeficiency virus; HFpEF—heart failure with preserved ejection fraction; HFrEF—heart failure with reduced ejection fraction; COPD—chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; VTE—venous thromboembolic disease.

3. The Interplay between Pulmonary Hypertension and Hyperglycemia

Recent studies have suggested a bidirectional relationship between PH and hyperglycemia [4,8,11]. When a diagnosis of PAH is made in elderly patients who present with cardiovascular comorbidities such as diabetes mellitus and obesity, early identification and treatment of PAH can improve outcomes. Endothelial dysfunction, a common denominator in both conditions, plays a pivotal role in their pathogenesis [1,11,12]. Endothelial injury and inflammation contribute to vascular remodeling and vasoconstriction in PH, and decreased endothelium-dependent vasodilation and hyperpermeability, is the initial stage of vasculopathy. Endothelial injury can serve as a vital prognostic indicator of diabetic complications [12] and a signal for impaired glucose metabolism and insulin signaling. The association between PH and hyperglycemia has significant clinical implications. Recent and ongoing analyses of a large European PAH database have revealed that patients with PAH and cardiovascular comorbidities such as diabetes benefit from PAH and diabetes treatment, with improvements in functional status, serologic biomarkers, and mortality risk [13]. Patients with PH, particularly those with PAH, are at increased risk of insulin resistance and DM. Conversely, individuals with DM have a higher prevalence of PH, contributing to worse outcomes and increased mortality [13]. Screening for PH in diabetic patients with unexplained dyspnea or exercise intolerance and evaluating for DM in those with PH may aid in early detection and intervention. Furthermore, optimizing glycemic control and addressing shared comorbidities such as obesity and obstructive sleep apnea are crucial in the management of both conditions. Figure 1 summarizes the interplay between the different subgroups of PH and diabetes mellitus (DM) and hyperglycemia.

5. Metabolic Dysregulation in Pulmonary Hypertension

Insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, and altered glucose metabolism are common features of both DM and PAH. Metabolic dysregulation contributes to excess cellular proliferation and mitochondrial dysfunction which promotes vascular remodeling in PAH progression. Some of the altered metabolic pathways that have been identified in PAH include abnormalities in glycolysis and glucose oxidation, fatty acid oxidation, and the tricarboxylic acid cycle. Glycolysis in particular provides a constant source of energy (ATP) in vascular endothelial cells relative to other types of cardiovascular cells [33]. Increasing evidence highlights the complexity of varied metabolic processes, in particular the reliance on glucose fermentation for growth and bioenergetics proliferation, regardless of oxygen availability (or traditionally considered “aerobic” conditions). One example of this “metabolic shift” is the Warburg effect, which describes an energy shift from mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation to aerobic glycolysis in which pyruvate is preferentially fermented to lactate, regardless of the presence of oxygen/aerobic conditions [33,34]. The Warburg effect has been observed not only in cancer, but also in pulmonary artery endothelial cells (PAECs), which produce large amounts of lactate in their preferential glycolytic state. In PAH, glucose metabolism is preferentially diverted from mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation towards cytoplasmic glycolysis in PAECs and pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells (PASMC). This glycolytic shift has not only been observed in primary cultured human pulmonary vascular cells, but also in cardiomyocytes derived from patients with PAH in vivo, in addition to PAH animal models [34,35]. How and “why” endothelial cells preferentially utilize glycogen and glycolysis to generate energy through a ‘Warburgesque’ phenotype is still not fully understood. Some have postulated that this glycolytic shift in PAECs allow these endothelial cells to use glucose for efficiently conferring a functional advantage over oxidative phosphorylation [33]. Moreover, endothelial cells are more resistant to hypoxia than other cell types because of preferential anaerobic glycolytic pathway particularly when glucose is readily available [33,36]. Contrastingly, when glucose levels are reduced, endothelial cells are more sensitive to hypoxic/low oxygen states, suggesting that glycolysis renders PAECs more resistant to hypoxia, and that hyperglycemia enhances this state of resistance. As such, PAH, hypoxemia and hyperglycemia are distinct clinical scenarios that inextricably bioenergetically linked. In fact, endothelial cells’ intracellular energy stores are in the form of glycogen, highlighting the importance of glycemic metabolism in endothelial cell biology [33].

Shared alterations in fatty acid oxidation are another commonality between PAH and DM, which has been observed in PAH cardiomyocytes [34,36]. Increased levels of carnitine and acylcarnitine in plasma from PAH patients, also support abnormal mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation [33]. Plasma metabolomic studies in PAH have demonstrated alterations in glycolysis, lipid metabolism, and altered bioenergetics [37]. Interestingly, these alterations in metabolism may extend to other types of PH [37,38]. In one study of chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH) patients, the plasma metabolome of CTEPH patients revealed that plasma acylcarnitines and fatty acid and glycerol, an essential component of triglycerides and an indicator of whole body lipolysis, was 2.4 times higher in the CTEPH patients compared to healthy controls [38]. Moreover, pathway enrichment analysis identified the following pathways as enriched in the CTEPH patients compared to controls: amino sugar metabolism, acyl choline, and long-chain fatty acid oxidation [38]. To summarize, metabolic and bioenergetic alterations stemming from mitochondrial abnormalities as well as vascular cell dysfunction play a notable role I both PH and DM. Nitric oxide signaling, glucose metabolism, fatty acid oxidation, and the TCA cycle are abnormal in PAH, along with alterations in the mitochondrial membrane potential, and PAEC and vascular cellular proliferation and DM share abnormal metabolic bioenergetics, particularly when it comes to endothelial cells, that facilitate a metabolic shift in endothelial cells promoting vasculopathy in both PAH and DM [36,37].

6. Oxidative Stress

Oxidative stress results from an imbalance of the prooxidant–antioxidant balance of the cell, resulting in reduced antioxidant cellular activity in favor of prooxidative processes that produce excess reactive oxygen species (ROS) that are deleterious to cellular processes. Oxidative stress has been associated with a variety of pathologic conditions, including diabetes mellitus (DM) [39] and is a common feature in both pulmonary hypertension and DM, sharing a pathway to vascular dysfunction [40]. In DM, auto-oxidation of glucose, imbalanced redox reactions, decreased tissue concentrations of low molecular weight antioxidants (such as diminished Glutathione and vitamin E) are potential causes of oxidative stress and increased ROS that result in overall impaired antioxidant defense enzymes and increased DM complications [40]. The increased production of free radicals and ROS and impairment of endogenous antioxidants can impair insulin signaling pathways and contribute to insulin resistance. In the context of pulmonary hypertension, oxidative stress also contributes to vascular damage and remodeling in both human and animal models of PAH [40,41]. Vasoconstriction promoted by oxidative stress is probably one of the most critical factors in the early stages of PAH. Oxidative stress plays a key role in impairing endothelial cell function, producing an increase in the synthesis and release of endothelium-derived constrictor factors such as endothelin-1 (ET-1) and a decrease in endogenous vasodilators such as nitric oxide (NO), contributing to the alterations in the homeostasis of vascular tone and permeability [39]. Oxidative stress thus leads to a reduction in NO bioavailability when ROS, in the form of O2, reacts with NO to form peroxynitrite (ONOO−) which, in turn, reacts with available tyrosine residues of proteins producing 3-nitrotyrosine, causing lung epithelial damage [40,41]. Therefore, oxidative stress and resulting excess ROS contribute directly to pulmonary vasoconstriction and impaired regulation of pulmonary vascular tone—critical contributing mechanisms in the development of pulmonary hypertension.

7. Hormonal Factors

Adiponectin, an adipokine involved in glucose metabolism, is often reduced in both insulin resistance and pulmonary hypertension. Adiponectin has anti-inflammatory effects and is involved in vascular homeostasis, with decreased adiponectin levels contributing to impaired insulin sensitivity and pulmonary vascular dysfunction [42]. Elevated plasma adiponectin levels are associated with the presence of pulmonary hypertension, increased heart failure admissions and mortality risk in African Americans [43]. Another adipokine, resistin, has been associated with insulin resistance and inflammation, and may also play a role in the development and progression of pulmonary hypertension [42]. Elevated leptin levels, often seen in obesity, are associated with insulin resistance, and can also alter inflammatory and immune responses. Another example of shared hormonal factors due to obesity when considering both DM and PH is in the role of adipose tissue in exogenous estrogen production. The role of estrogen in both these diseases, particularly how it relates to adiposity, is discussed in detail later.

8. Genetic Susceptibility

Individuals with DM and PAH may have shared genetic factors that predispose the development of these diseases. Genome-wide association studies have implicated overlapping pathogenic pathways through identification of common genetic variants associated with both conditions. Some of these shared inherited pathways include associated nuclear and mitochondrial mutations on metabolism. Recent work in mitochondrial genetics in PAH have identified inherited biologic pathways that are preserved through maternal lineage [44]. Mitochondria genes encode oxidative phosphorylation proteins crucial for bioenergetic function that are genetically transmitted to subsequent lineages through the maternal inheritance. Mitochondrial (mt) DNA mutations occur with greater frequency compared to the nuclear genome [44,45]. Mitochondrial haplogroups are defined collections of mutations that are maternally inherited and are associated with increased or decreased risk of metabolic and autoimmune diseases, and have been associated with various types of cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and several types of cancer [46,47]. Other genetic associations between PAH and altered metabolic pathway include implications from the effects of heterozygous germline mutations of the BMPR2 gene, which is identifiable in approximately 75% of heritable (or familial) PAH and 20% of idiopathic PAH [48,49]. BMPR2 is a serine-threonine kinase receptor of transforming growth factor (TGF)-β superfamily that signals to inhibit cell growth and studies with genetic siRNA knockdown of BMPR2 in human PAH endothelial cells demonstrate higher levels of glycolysis; healthy human endothelial cells transfected with mutant BMPR2 have greater glycolysis and increased expression of glycolytic mediator biosynthetic pathways [48,49]. Shared inheritance of particular mutations that encode genes that are important for metabolic regulation of glycolysis and intracellular bioenergetics are common between DM and PAH.

10. Conclusions

Pulmonary hypertension and hyperglycemia with associated insulin resistance share common pathological pathways, suggesting a potential interconnection. While the precise mechanisms linking these conditions require further investigation, recognizing and addressing the coexistence of pulmonary hypertension and metabolic disorders is essential for effective patient care. Understanding these intricate relationships is crucial for developing comprehensive management strategies that address both pulmonary hypertension and metabolic disorders in affected individuals. Interdisciplinary approaches, involving the combination of expertise from both cardiovascular and metabolic specialists, lifestyle modifications, pharmacological agents, and emerging therapies offer promise in addressing the complex interplay between insulin resistance and pulmonary hypertension. Recognizing the shared molecular mechanisms and risk factors provides a foundation for developing integrated therapeutic strategies that target both conditions simultaneously, potentially improving overall patient outcomes. Further research in large-scale cardiovascular registries is essential to unravel the complexities of this interplay and refine treatment modalities for individuals facing the challenges of comorbid pulmonary hypertension and insulin resistance.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, O.B. and L.M.P.; data curation, O.B. and L.M.P.; writing—original draft preparation, O.B. and L.M.P.; writing—review and editing, O.B. and L.M.P. supervision, L.M.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Humbert, M.; Guignabert, C.; Bonnet, S.; Dorfmüller, P.; Klinger, J.R.; Nicolls, M.R.; Olschewski, A.J.; Pullamsetti, S.S.; Schermuly, R.T.; Stenmark, K.R.; et al. Pathology and pathobiology of pulmonary hypertension: State of the art and research perspectives. Eur. Respir. J. 2019, 53, 1801887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simonneau, G.; Montani, D.; Celermajer, D.S.; Denton, C.P.; Gatzoulis, M.A.; Krowka, M.; Williams, P.G.; Souza, R. Haemodynamic definitions and updated clinical classification of pulmonary hypertension. Eur. Respir. J. 2019, 53, 1801913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humbert, M.; Kovacs, G.; Hoeper, M.M.; Badagliacca, R.; Berger, R.M.; Brida, M.; Carlsen, J.; Coats, A.J.; Escribano-Subias, P.; Ferrari, P.; et al. 2022 ESC/ERS Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension. Eur. Respir. J. 2023, 61, 2200879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, W.; Janocha, A.J.; Erzurum, S.C. Metabolism in Pulmonary Hypertension. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2021, 83, 551–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, W.; Erzurum, S.C. Endothelial cell energy metabolism, proliferation, and apoptosis in pulmonary hypertension. Compr. Physiol. 2011, 1, 357–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, X.F.; Su, Y.C. Vascular Metabolic Mechanisms of Pulmonary Hypertension. Curr. Med. Sci. 2020, 40, 444–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, W.; Kaneko, F.T.; Zheng, S.; Comhair, S.A.A.; Janocha, A.J.; Goggans, T.; Thunnissen, F.B.J.M.; Farver, C.; Hazen, S.L.; Jennings, C.; et al. Increased arginase II and decreased NO synthesis in endothelial cells of patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension. FASEB J. 2004, 18, 1746–1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willson, C.; Watanabe, M.; Tsuji-Hosokawa, A.; Makino, A. Pulmonary vascular dysfunction in metabolic syndrome. J. Physiol. 2019, 597, 1121–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Keramidas, G.; Gourgoulianis, K.I.; Kotsiou, O.S. Venous Thromboembolic Disease in Chronic Inflammatory Lung Diseases: Knowns and Unknowns. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Condliffe, R.; Durrington, C.; Hameed, A.; Lewis, R.A.; Venkateswaran, R.; Gopalan, D.; Dorfmüller, P. Clinical-radiological-pathological correlation in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur. Respir. Rev. 2023, 32, 230138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Yang, L.; Jia, Y.; Balistrieri, A.; Fraidenburg, D.R.; Wang, J.; Tang, H.; Yuan, J.X. Pathogenic Mechanisms of Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension: Homeostasis Imbalance of Endothelium-Derived Relaxing and Contracting Factors. JACC Asia 2022, 2, 787–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- An, Y.; Xu, B.T.; Wan, S.R.; Ma, X.M.; Long, Y.; Xu, Y.; Jiang, Z.Z. The role of oxidative stress in diabetes mellitus-induced vascular endothelial dysfunction. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2023, 22, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenkranz, S.; Pausch, C.; Coghlan, J.G.; Huscher, D.; Pittrow, D.; Grünig, E.; Staehler, G.; Vizza, C.D.; Gall, H.; Distler, O.; et al. Risk stratification and response to therapy in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension and comorbidities: A COMPERA analysis. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 2023, 42, 102–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lampropoulou, I.T.; Stangou, Μ.; Sarafidis, P.; Gouliovaki, A.; Giamalis, P.; Tsouchnikas, I.; Didangelos, T.; Papagianni, A. TNF-α pathway and T-cell immunity are activated early during the development of diabetic nephropathy in Type II Diabetes Mellitus. Clin. Immunol. 2020, 215, 108423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavkov, M.E.; Weil, E.J.; Fufaa, G.D.; Nelson, R.G.; Lemley, K.V.; Knowler, W.C.; Niewczas, M.A.; Krolewski, A.S. Tumor necrosis factor receptors 1 and 2 are associated with early glomerular lesions in type 2 diabetes. Kidney Int. 2016, 89, 226–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jang, D.I.; Lee, A.H.; Shin, H.Y.; Song, H.R.; Park, J.H.; Kang, T.B.; Lee, S.-R.; Yang, S.-H. The role of tumor necrosis factor alpha (tnf-α) in autoimmune disease and current tnf-α inhibitors in therapeutics. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 2719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, H.; Zhao, Y.; Li, S.; Wu, H.; Ma, D.; Wan, C. TNF-α and IL-8 levels are positively correlated with hypobaric hypoxic pulmonary hypertension and pulmonary vascular remodeling in rats. Open Life Sci. 2023, 18, 20220650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mauer, J.; Chaurasia, B.; Goldau, J.; Vogt, M.C.; Ruud, J.; Nguyen, K.D.; Theurich, S.; Hausen, A.C.; Schmitz, J.; Brönneke, H.S.; et al. Signaling by IL-6 promotes alternative activation of macrophages to limit endotoxemia and obesity-associated resistance to insulin. Nat. Immunol. 2014, 15, 423–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, T.; Song, J.; Gao, J.; Cheng, J.; Xie, H.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Y.-H.; Gao, Z.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; et al. Adipocyte-derived kynurenine promotes obesity and insulin resistance by activating the AhR/STAT3/IL-6 signaling. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 3489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, T.; Wang, P.; Wang, X.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Feng, Y.; Wang, Q.; Guo, X.; et al. Inflammation and Insulin Resistance in Diabetic Chronic Coronary Syndrome Patients. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yaku, A.; Inagaki, T.; Asano, R.; Okazawa, M.; Mori, H.; Sato, A.; Hia, F.; Masaki, T.; Manabe, Y.; Ishibashi, T.; et al. Regnase-1 Prevents Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension Through mRNA Degradation of Interleukin-6 and Platelet-Derived Growth Factor in Alveolar Macrophages. Circulation 2022, 146, 1006–1022, Erratum in Circulation 2022, 146, e280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toshner, M.; Rothman, A. IL-6 in pulmonary hypertension: Why novel is not always best. Eur. Respir. J. 2020, 55, 2000314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toshner, M.; Church, C.; Harbaum, L.; Rhodes, C.; Moreschi, S.S.V.; Liley, J.; Jones, R.; Arora, A.; Batai, K.; Desai, A.A.; et al. Mendelian randomisation and experimental medicine approaches to interleukin-6 as a drug target in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur. Respir. J. 2022, 59, 2002463, Erratum in Eur. Respir. J. 2022, 60, 2052463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, X.; Bijli, K.M.; Ramirez, A.; Murphy, T.C.; Kleinhenz, J.; Hart, C.M. Hypoxia downregulates PPARγ via an ERK1/2-NF-κB-Nox4-dependent mechanism in human pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2013, 63, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stanimirovic, J.; Radovanovic, J.; Banjac, K.; Obradovic, M.; Essack, M.; Zafirovic, S.; Gluvic, Z.; Gojobori, T.; Isenovic, E.R. Role of C-Reactive Protein in Diabetic Inflammation. Mediat. Inflamm. 2022, 2022, 3706508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ben, J.; Jiang, B.; Wang, D.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Qi, Y.; Tong, X.; Chen, L.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Major vault protein suppresses obesity and atherosclerosis through inhibiting IKK-NF-κB signaling mediated inflammation. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, F.; Huang, Y.; Song, Z.; Zhou, H.J.; Zhang, H.; Perry, R.J.; Shulman, G.I.; Min, W. Mitophagy-mediated adipose inflammation contributes to type 2 diabetes with hepatic insulin resistance. J. Exp. Med. 2021, 218, e20201416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maimaitiaili, N.; Zeng, Y.; Ju, P.; Zhakeer, G.; Guangxi, E.; Yao, H.; Shi, Y.; Zhai, M.; Zhuang, J.; Peng, W.; et al. NLRC3 deficiency promotes hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension development via IKK/NF-κB p65/HIF-1α pathway. Exp. Cell Res. 2023, 431, 113755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, M.; Wu, X.; Wang, J.; He, M.; Han, H.; Hu, S.; Xu, J.; Yang, M.; Tan, Q.; Wang, Y.; et al. Paeoniflorin attenuates monocrotaline-induced pulmonary arterial hypertension in rats by suppressing TAK1-MAPK/NF-κB pathways. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2022, 19, 681–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, T.Y.; Chiu, C.J.; Kuan, C.H.; Chen, F.H.; Shen, Y.C.; Wu, C.H.; Hsu, Y.H. IL-29 promoted obesity-induced inflammation and insulin resistance. Cell Mol. Immunol. 2020, 17, 369–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chattopadhyay, D.; Das, S.; Guria, S.; Basu, S.; Mukherjee, S. Fetuin-A regulates adipose tissue macrophage content and activation in insulin resistant mice through MCP-1 and iNOS: Involvement of IFNγ-JAK2-STAT1 pathway. Biochem. J. 2021, 478, 4027–4043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magoń, W.; Stępniewski, J.; Waligóra, M.; Jonas, K.; Przybylski, R.; Podolec, P.; Kopeć, G. Changes in Inflammatory Markers in Patients with Chronic Thromboembolic Pulmonary Hypertension Treated with Balloon Pulmonary Angioplasty. Cells 2022, 11, 1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Potente, M.; Carmeliet, P. The Link between Angiogenesis and Endothelial Metabolism. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2017, 79, 43–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Luo, F.; Wu, P.; Huang, Y.; Das, A.; Chen, S.; Chen, J.; Hu, X.; Li, F.; Fang, Z.; et al. Metabolomics reveals metabolite changes of patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension in China. J. Cell Mol. Med. 2020, 24, 2484–2496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemnes, A.R.; Brittain, E.L.; Trammell, A.W.; Fessel, J.P.; Austin, E.D.; Penner, N.; Maynard, K.B.; Gleaves, L.; Talati, M.; Absi, T.; et al. Evidence for right ventricular lipotoxicity in heritable pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2014, 189, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pokharel, M.D.; Marciano, D.P.; Fu, P.; Franco, M.C.; Unwalla, H.; Tieu, K.; Fineman, J.R.; Wang, T.; Black, S.M. Metabolic reprogramming, oxidative stress, and pulmonary hypertension. Redox Biol. 2023, 64, 102797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulin, R.; Michelakis, E.D. The metabolic theory of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Circ. Res. 2014, 115, 148–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heresi, G.A.; Mey, J.T.; Bartholomew, J.R.; Haddadin, I.S.; Tonelli, A.R.; Dweik, R.A.; Kirwan, J.P.; Kalhan, S.C. Plasma metabolomic profile in chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Pulm. Circ. 2020, 10, 2045894019890553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papachristoforou, E.; Lambadiari, V.; Maratou, E.; Makrilakis, K. Association of Glycemic Indices (Hyperglycemia, Glucose Variability, and Hypoglycemia) with Oxidative Stress and Diabetic Complications. J. Diabetes Res. 2020, 2020, 7489795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poyatos, P.; Gratacós, M.; Samuel, K.; Orriols, R.; Tura-Ceide, O. Oxidative Stress and Antioxidant Therapy in Pulmonary Hypertension. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulton, D.J.R.; Li, X.; Bordan, Z.; Haigh, S.; Bentley, A.; Chen, F.; Barman, S.A. Reactive oxygen and nitrogen species in the development of pulmonary hypertension. Antioxidants 2017, 6, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perrotta, F.; Nigro, E.; Mollica, M.; Costigliola, A.; D’agnano, V.; Daniele, A.; Bianco, A.; Guerra, G. Pulmonary Hypertension and Obesity: Focus on Adiponectin. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lakshmanan, S.; Jankowich, M.; Wu, W.C.; Abbasi, S.; Morrison, A.R.; Choudhary, G. Association of plasma adiponectin with pulmonary hypertension, mortality and heart failure in African Americans: Jackson Heart Study. Pulm. Circ. 2020, 10, 2045894020961242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kraja, A.T.; Liu, C.; Fetterman, J.L.; Graff, M.; Have, C.T.; Gu, C.; Yanek, L.R.; Feitosa, M.F.; Arking, D.E.; Chasman, D.I.; et al. Associations of Mitochondrial and Nuclear Mitochondrial Variants and Genes with Seven Metabolic Traits. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2019, 104, 112–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallace, D.C. Mitochondrial DNA variation in human radiation and disease. Cell 2015, 163, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farha, S.; Hu, B.; Comhair, S.; Zein, J.; Dweik, R.; Erzurum, S.C.; Aldred, M.A. Mitochondrial Haplogroups and Risk of Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0156042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aldred, M.A.; Comhair, S.A.; Varella-Garcia, M.; Asosingh, K.; Xu, W.; Noon, G.P.; Thistlethwaite, P.A.; Tuder, R.M.; Erzurum, S.C.; Geraci, M.W.; et al. Somatic chromosome abnormalities in the lungs of patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2010, 182, 1153–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The International PPH Consortium; Lane, K.B.; Machado, R.D.; Pauciulo, M.W.; Thomson, J.R.; Phillips, J.A., 3rd; Loyd, J.E.; Nichols, W.C.; Trembath, R.C. Heterozygous germline mutations in BMPR2, encoding a TGF-beta receptor, cause familial primary pulmonary hypertension. Nat. Genet. 2000, 26, 81–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diebold, I.; Hennigs, J.K.; Miyagawa, K.; Li, C.G.; Nickel, N.P.; Kaschwich, M.; Cao, A.; Wang, L.; Reddy, S.; Chen, P.-I.; et al. BMPR2 preserves mitochondrial function and DNA during reoxygenation to promote endothelial cell survival and reverse pulmonary hypertension. Cell Metab. 2015, 21, 596–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naderi, N.; Boobejame, P.; Bakhshandeh, H.; Amin, A.; Taghavi, S.; Maleki, M. Insulin resistance in pulmonary arterial hypertension, is it a novel disease modifier? Res. Cardiovasc. Med. 2014, 3, e19710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradley, E.A.; Bradley, D. Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension and Insulin Resistance. J. Mol. Genet. Med. 2014, 2 (Suppl. S1), 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farha, S.; Comhair, S.; Hou, Y.; Park, M.M.; Sharp, J.; Peterson, L.; Willard, B.; Zhang, R.; DiFilippo, F.P.; Neumann, D.R.; et al. Metabolic endophenotype associated with right ventricular glucose uptake in pulmonary hypertension. Pulm. Circ. 2021, 11, 20458940211054325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimura, H.; Ota, H.; Kimura, Y.; Takasawa, S. Effects of Intermittent Hypoxia on Pulmonary Vascular and Systemic Diseases. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mair, K.M.; Gaw, R.; MacLean, M.R. Obesity, estrogens and adipose tissue dysfunction—Implications for pulmonary arterial hypertension. Pulm. Circ. 2020, 10, 2045894020952019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLean, L.L.; Pellino, K.; Brewis, M.; Peacock, A.; Johnson, M.; Church, A.C. The obesity paradox in pulmonary arterial hypertension: The Scottish perspective. ERJ Open Res. 2019, 5, 00241–2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poms, A.D.; Turner, M.; Farber, H.W.; Meltzer, L.A.; McGoon, M.D. Comorbid conditions and outcomes in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension: A REVEAL registry analysis. Chest 2013, 144, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weatherald, J.; Huertas, A.; Boucly, A.; Guignabert, C.; Taniguchi, Y.; Adir, Y.; Jevnikar, M.; Savale, L.; Jaïs, X.; Peng, M.; et al. Association between BMI and obesity with survival in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Chest 2018, 154, 872–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawut, S.M.; Archer-Chicko, C.L.; DeMichele, A.; Fritz, J.S.; Klinger, J.R.; Ky, B.; Palevsky, H.I.; Palmisciano, A.J.; Patel, M.; Pinder, D.; et al. Anastrozole in pulmonary arterial hypertension. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2017, 195, 360–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, A.F.; Ewart, M.A.; Mair, K.; Nilsen, M.; Dempsie, Y.; Loughlin, L.; Maclean, M.R. Oestrogen receptor alpha in pulmonary hypertension. Cardiovasc. Res 2015, 106, 206–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawut, S.M.; Pinder, D.; Al-Naamani, N.; McCormick, A.; Palevsky, H.I.; Fritz, J.; Smith, K.A.; Mazurek, J.A.; Doyle, M.F.; MacLean, M.R.; et al. Fulvestrant for the treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2019, 16, 1456–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Austin, E.D.; Talati, M.; Fessel, J.P.; Farber-Eger, E.H.; Brittain, E.L.; Hemnes, A.R.; Loyd, J.E.; West, J. Oestrogen inhibition reverses pulmonary arterial hypertension and associated metabolic defects. Eur. Respir. J. 2017, 50, 1602337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).