Sentinel Lymph Node in Endometrial Hyperplasia: State of the Art and Future Perspectives

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

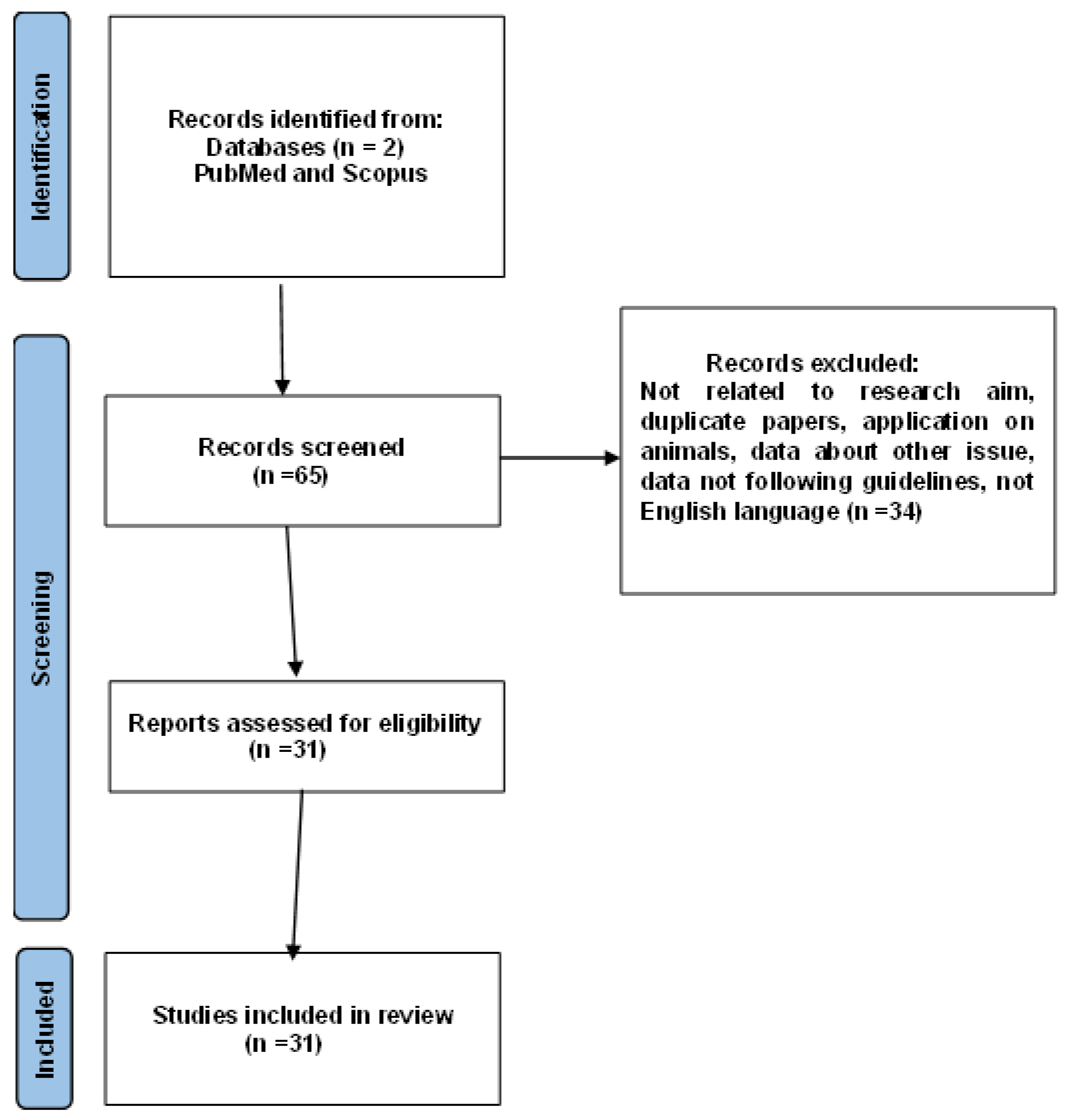

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nees, L.K.; Heublein, S.; Steinmacher, S.; Juhasz-Böss, I.; Brucker, S.; Tempfer, C.B.; Wallwiener, M. Endometrial Hyperplasia as a Risk Factor of Endometrial Cancer. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2022, 306, 407–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ring, K.L.; Mills, A.M.; Modesitt, S.C. Endometrial Hyperplasia. Obstet. Gynecol. 2022, 140, 1061–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanderson, P.A.; Critchley, H.O.D.; Williams, A.R.W.; Arends, M.J.; Saunders, P.T.K. New Concepts for an Old Problem: The Diagnosis of Endometrial Hyperplasia. Hum. Reprod. Update 2017, 23, 232–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Touhami, O.; Grégoire, J.; Renaud, M.-C.; Sebastianelli, A.; Grondin, K.; Plante, M. The Utility of Sentinel Lymph Node Mapping in the Management of Endometrial Atypical Hyperplasia. Gynecol. Oncol. 2018, 148, 485–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Management of Endometrial Intraepithelial Neoplasia or Atypical Endometrial Hyperplasia: ACOG Clinical Consensus No. 5. Obstet. Gynecol. 2023, 142, 735–744. [CrossRef]

- Gullo, G.; Cucinella, G.; Chiantera, V.; Dellino, M.; Cascardi, E.; Török, P.; Herman, T.; Garzon, S.; Uccella, S.; Laganà, A.S. Fertility-Sparing Strategies for Early-Stage Endometrial Cancer: Stepping towards Precision Medicine Based on the Molecular Fingerprint. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannella, L.; Grelloni, C.; Bernardi, M.; Cicoli, C.; Lavezzo, F.; Sartini, G.; Natalini, L.; Bordini, M.; Petrini, M.; Petrucci, J.; et al. Atypical Endometrial Hyperplasia and Concurrent Cancer: A Comprehensive Overview on a Challenging Clinical Condition. Cancers 2024, 16, 914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Kallas, H.; Cooper, P.; Varma, S.; Peplinski, J.; Kuo, Y.-H.; Miller, B.; Aikman, N.; Borowsky, M.E.; Haggerty, A.; ElSahwi, K. Evaluation of Sentinel Lymph Nodes in Complex Atypical Endometrial Hyperplasia. Lymphatics 2024, 2, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuo, K.; Ciesielski, K.M.; Mandelbaum, R.S.; Lee, M.W.; Jooya, N.D.; Roman, L.D.; Wright, J.D. Lymph Node Evaluation for Endometrial Hyperplasia: A Nationwide Analysis of Minimally Invasive Hysterectomy in the Ambulatory Setting. Surg. Endosc. 2023, 37, 6163–6171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, J.J.; Rios-Doria, E.; Park, K.J.; Broach, V.A.; Alektiar, K.M.; Jewell, E.L.; Zivanovic, O.; Sonoda, Y.; Abu-Rustum, N.R.; Leitao, M.M.; et al. Sentinel Lymph Node Mapping in Patients with Endometrial Hyperplasia: A Practice to Preserve or Abandon? Gynecol. Oncol. 2023, 168, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vieira-Serna, S.; Peralta, J.; Viveros-Carreño, D.; Rodriguez, J.; Feliciano-Alfonso, J.E.; Pareja, R. Sentinel Lymph Node Assessment in Patients with Atypical Endometrial Hyperplasia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2024, 34, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pöschke, P.; Gass, P.; Krückel, A.; Keller, K.; Erber, R.; Hartmann, A.; Beckmann, M.W.; Emons, J. Clinical and Surgical Evaluation of Sentinel Node Biopsy in Patients with Early-Stage Endometrial Cancer and Atypical Hyperplasia. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd. 2024, 84, 470–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blandamura, S.; Boccato, P.; Spadaro, M.; Litta, P.; Chiarelli, S. Endometrial Hyperplasia with Berrylike Squamous Metaplasia and Pilomatrixomalike Shadow Cells. Report of an Intriguing Cytohistologic Case. Acta Cytol. 2002, 46, 887–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uptake and Outcomes of Sentinel Lymph Node Mapping in Women with Atypical Endometrial Hyperplasia—PubMed. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33831939/ (accessed on 3 February 2025).

- Rosati, A.; Vargiu, V.; Capozzi, V.A.; Giannarelli, D.; Palmieri, E.; Baroni, A.; Perrone, E.; Berretta, R.; Cosentino, F.; Scambia, G.; et al. Concurrent Endometrial Cancer in Atypical Endometrial Hyperplasia and the Role of Sentinel Lymph Nodes: Clinical Insights from a Multicenter Experience. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2024, 34, 1011–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capozzi, V.A.; Sozzi, G.; Butera, D.; Chiantera, V.; Ghi, T.; Berretta, R. Nodal Assessment in Endometrial Atypical Hyperplasia. Gynecol. Obstet. Investig. 2022, 87, 226–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGowan, M.; Addley, S.; Davies, J.; Abdul, S.; Asher, V.; Bali, A.; Dudill, W.; Phillips, A. Does the Character of the Hospital of Primary Management Influence Outcomes in Patients Treated for Presumed Early Stage Endometrial Cancer and Atypical Endometrial Hyperplasia: A Comparison of Outcomes from a Cancer Unit and Cancer Centre. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2022, 42, 3362–3367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matanes, E.; Amajoud, Z.; Kogan, L.; Mitric, C.; Ismail, S.; Raban, O.; Knigin, D.; Levin, G.; Bahoric, B.; Ferenczy, A.; et al. Is Sentinel Lymph Node Assessment Useful in Patients with a Preoperative Diagnosis of Endometrial Intraepithelial Neoplasia? Gynecol. Oncol. 2023, 168, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vetter, M.H.; Smith, B.; Benedict, J.; Hade, E.M.; Bixel, K.; Copeland, L.J.; Cohn, D.E.; Fowler, J.M.; O’Malley, D.; Salani, R.; et al. Preoperative Predictors of Endometrial Cancer at Time of Hysterectomy for Endometrial Intraepithelial Neoplasia or Complex Atypical Hyperplasia. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2020, 222, 60.e1–60.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nahshon, C.; Leitao, M.M.; Lavie, O.; Schmidt, M.; Younes, G.; Ostrovsky, L.; Assaf, W.; Segev, Y. Surgical Nodal Assessment for Endometrial Hyperplasia—A Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review. Gynecol. Oncol. 2024, 188, 140–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, A.; Tsur, Y.; Tako, E.; Levin, I.; Gil, Y.; Michaan, N.; Grisaru, D.; Laskov, I. Incidence of Endometrial Carcinoma in Patients with Endometrial Intraepithelial Neoplasia Versus Atypical Endometrial Polyp. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer. 2023, 33, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, L.M.; Erfani, H.; Furey, K.B.; Matsuo, K.; Guo, X.M. Risks and Benefits of Sentinel Lymph Node Evaluation in the Management of Endometrial Intraepithelial Neoplasia. Expert Rev. Anticancer Ther. 2024, 24, 745–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.A.; Olshan, A.F.; Bae-Jump, V.L.; Ogunleye, A.A.; Smith, S.; Black-Grant, S.; Nichols, H.B. Lymphedema Self-Assessment Among Endometrial Cancer Survivors. Cancer Causes Control 2024, 35, 771–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albolino, S.; Bellandi, T.; Cappelletti, S.; Di Paolo, M.; Fineschi, V.; Frati, P.; Offidani, C.; Tanzini, M.; Tartaglia, R.; Turillazzi, E. New Rules on Patient’s Safety and Professional Liability for the Italian Health Service. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2019, 20, 615–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- La Russa, R.; Viola, R.V.; D’Errico, S.; Aromatario, M.; Maiese, A.; Anibaldi, P.; Napoli, C.; Frati, P.; Fineschi, V. Analysis of Inadequacies in Hospital Care Through Medical Liability Litigation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Busardò, F.P.; Frati, P.; Santurro, A.; Zaami, S.; Fineschi, V. Errors and Malpractice Lawsuits in Radiology: What the Radiologist Needs to Know. Radiol. Med. 2015, 120, 779–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeMari, J.A.; Shalowitz, D.I. Routine Informed Consent for Mismatch Repair Testing in Endometrial Cancers: Review and Ethical Analysis. Gynecol. Oncol. 2022, 167, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, H.K.; Shim, S.-H.; Lee, M.; Lee, W.M.; Eoh, K.J.; Yoo, H.J.; Kim, M.K.; Kim, M.K.; Lee, K.-B.; So, K.A.; et al. Informed Consent Forms for Gynecologic Cancer Surgery: Recommendations from the Korean Society of Gynecologic Oncology. J. Gynecol. Oncol. 2022, 33, e42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeppesen, M.M.; Mogensen, O.; Dehn, P.; Jensen, P.T. Needs and Priorities of Women with Endometrial and Cervical Cancer. J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2015, 36, 122–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quattrocchi, A.; Del Fante, Z.; Di Fazio, N.; Romano, S.; Volonnino, G.; Fazio, V.; Santoro, P.; De Gennaro, U. Personalized Medicine in Psychiatric Disorders: Prevention and Bioethical Questions. Clin. Ter. 2019, 170, e421–e424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Napoletano, G.; Paola, L.D.; Circosta, F.; Vergallo, G.M. Right to Be Forgotten: European Instruments to Protect the Rights of Cancer Survivors. Acta Biomed. Atenei Parm. 2024, 95, e2024114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fournier, E.M. Oncofertility and the Rights to Future Fertility. JAMA Oncol. 2016, 2, 249–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, L.; Labied, S.; Chiaradia, F.; Munaut, C.; Nisolle, M. Cancer and the right to motherhood. Rev. Med. Liege 2014, 69, 188–193. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shree Ca, P.; Garg, M.; Bhati, P.; Sheejamol, V.S. Should We Prioritise Proper Surgical Staging for Patients with Atypical Endometrial Hyperplasia (AEH)? Experience from a Single-Institution Tertiary Care Oncology Centre. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2024, 303, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Routine SLN Biopsy for Endometrial Intraepithelial Neoplasia: A Pragmatic Approach or Over-Treatment? PubMed. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36577526/ (accessed on 4 February 2025).

- Papadia, A.; Gasparri, M.L.; Siegenthaler, F.; Imboden, S.; Mohr, S.; Mueller, M.D. FIGO Stage IIIC Endometrial Cancer Identification Among Patients with Complex Atypical Hyperplasia, Grade 1 and 2 Endometrioid Endometrial Cancer: Laparoscopic Indocyanine Green Sentinel Lymph Node Mapping Versus Frozen Section of the Uterus, Why Get Around the Problem? J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 143, 491–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bedyńska, M.; Szewczyk, G.; Klepacka, T.; Sachadel, K.; Maciejewski, T.; Szukiewicz, D.; Fijałkowska, A. Sentinel Lymph Node Mapping Using Indocyanine Green in Patients with Uterine and Cervical Neoplasms: Restrictions of the Method. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2019, 299, 1373–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomaier, L.; Jager, L.; Stone, R.; Wethington, S.; Fader, A.; Tanner, E.J. Risk of Empty Lymph Node Packets in Sentinel Lymph Node Mapping for Endometrial Cancer Using Indocyanine Green. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2019, 29, 513–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lörsch, A.M.; Jung, J.; Lange, S.; Pfarr, N.; Mogler, C.; Illert, A.L. Personalized medicine in oncology. Pathologie 2024, 45, 180–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volonnino, G.; Paola, L.D.; Spadazzi, F.; Serri, F.; Ottaviani, M.; Zamponi, M.V.; Arcangeli, M.; Russa, R.L. Artificial intelligence and Forensic Medicine: The state of the art and future perspectives. La Clin. Ter. 2024, 175, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, G.; Matanes, E.; Brezinov, Y.; Ferenczy, A.; Pelmus, M.; Brodeur, M.N.; Salvador, S.; Lau, S.; Gotlieb, W.H. Machine Learning for Prediction of Concurrent Endometrial Carcinoma in Patients Diagnosed with Endometrial Intraepithelial Neoplasia. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2024, 50, 108006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Achi, V.; Burling, M.; Al-Aker, M. Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy at Robotic-Assisted Hysterectomy for Atypical Hyperplasia and Endometrial Cancer. J. Robot. Surg. 2022, 16, 1111–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casarin, J.; Multinu, F.; Tortorella, L.; Cappuccio, S.; Weaver, A.L.; Ghezzi, F.; Cilby, W.; Kumar, A.; Langstraat, C.; Glaser, G.; et al. Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy for Robotic-Assisted Endometrial Cancer Staging: Further Improvement of Perioperative Outcomes. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2020, 30, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herling, S.F.; Havemann, M.C.; Palle, C.; Møller, A.M.; Thomsen, T. Robotic-Assisted Laparoscopic Hysterectomy Seems Safe in Women with Early-Stage Endometrial Cancer. Dan Med. J. 2015, 62, A5109. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sinno, A.K.; Fader, A.N.; Roche, K.L.; Giuntoli, R.L.; Tanner, E.J. A Comparison of Colorimetric versus Fluorometric Sentinel Lymph Node Mapping during Robotic Surgery for Endometrial Cancer. Gynecol. Oncol. 2014, 134, 281–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Ref. | Number of Patients | Preoperative Histological Diagnosis | Lymph Node Staging | Postoperative Histological Diagnosis | Positive Lymph Nodes on Definitive Histological Examination | Postoperative Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [12] | 102 | Atypical endometrial hyperplasia (n = 20) and early-stage endometrial cancer (n = 82) | Sentinel node biopsy (n = 96)/sentinel node biopsy and pelvic lymphadenectomy (n = 6) | Atypical endometrial hyperplasia (n = 9) Endometrioid carcinoma (n = 90) Uterine serous carcinoma (n = 2) Adenosquamous endometrial cancer (n = 1) | 3; 3.6% rate of positive SNBs was found in patients with EC | C * |

| [8] | 113 | Complex atypical hyperplasia (n = 74)/complex atypical hyperplasia bordering on cancer or unable to rule out cancer (n = 39) | Sentinel node sampling (n = 69), no sentinel node biopsy (n = 44) | No hyperplasia (n = 20) Complex atypical hyperplasia (n = 41) Endometrioid adenocarcinoma (n = 52) | 1 ITC | C |

| [10] | 221 | EIN, complex atypical hyperplasia, and hyperplasia bordering on carcinoma | SLN mapping/excision (n = 161) | Endometrioid carcinoma (n = 98) Adenosarcoma (n = 1) CAH (n = 35) CAH bordering on carcinoma (n = 15) Atypical hyperplasia (n = 50) Benign (n = 22) | 3 | C |

| [14] | 10,266 | Complex atypical endometrial hyperplasia | Sentinel lymph node mapping in 620 (6.0%), lymph node dissection in 538 (5.2%), and no lymphatic evaluation in 9108 | NA * | NA | C |

| [11] | 10,217 | Atypical hyperplasia/endometrial intraepithelial neoplasia and endometrial cancer | 1044 in SLN group and 9173 in the non-nodal assessment group | NA | 1.6%, 7 SLN | C |

| [4] | 120 | 70 patients had diagnosis of “AH only” and 50 had preoperative diagnosis of “AH-C” | SLN mapping followed by pelvic lymphadenectomy | 64/120 (53.3%) patients found to have EC on final pathology: 58 stage IA, 3 IB, and 3 IIIC1. 30/70 (44.3%) with AH and 33/50 (66%) with AH-C had EC on final pathology | 4/120 had lymph node involvement. In patients with EC with preoperative diagnosis of “AH”, none had lymph node metastasis (0/31), 12.1% (4/33) in patients with AH-C | NA |

| [15] | 460 | Atypical endometrial hyperplasia | 192 received standard surgical management (no SLN) and 268 underwent sentinel lymph node biopsy | 47.2% of patients updated to endometrial cancer on final histopathological examination | Lymph node metastases were identified in 7.6% of patients with concurrent endometrial cancer who underwent nodal assessment | C |

| [9] | 49,698 | Endometrial hyperplasia | 2847 (5.7%) patients had lymph node evaluation at time of hysterectomy | NA | NA | NA |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Billone, V.; De Paola, L.; Conti, E.; Borsellino, L.; Kozinszky, Z.; Giampaolino, P.; Suranyi, A.; Della Corte, L.; Andrisani, A.; Cucinella, G.; et al. Sentinel Lymph Node in Endometrial Hyperplasia: State of the Art and Future Perspectives. Cancers 2025, 17, 776. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17050776

Billone V, De Paola L, Conti E, Borsellino L, Kozinszky Z, Giampaolino P, Suranyi A, Della Corte L, Andrisani A, Cucinella G, et al. Sentinel Lymph Node in Endometrial Hyperplasia: State of the Art and Future Perspectives. Cancers. 2025; 17(5):776. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17050776

Chicago/Turabian StyleBillone, Valentina, Lina De Paola, Eleonora Conti, Letizia Borsellino, Zoltan Kozinszky, Pierluigi Giampaolino, Andrea Suranyi, Luigi Della Corte, Alessandra Andrisani, Gaspare Cucinella, and et al. 2025. "Sentinel Lymph Node in Endometrial Hyperplasia: State of the Art and Future Perspectives" Cancers 17, no. 5: 776. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17050776

APA StyleBillone, V., De Paola, L., Conti, E., Borsellino, L., Kozinszky, Z., Giampaolino, P., Suranyi, A., Della Corte, L., Andrisani, A., Cucinella, G., Marinelli, S., & Gullo, G. (2025). Sentinel Lymph Node in Endometrial Hyperplasia: State of the Art and Future Perspectives. Cancers, 17(5), 776. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17050776