Abstract

The acceleration of stunting reduction in Indonesia is one of the priority agendas in the health sector, its implementation being through various regional and tiered approaches. This paper aims to manage management using an integrated system framework approach at the regional level and to support the acceleration of stunting reduction nationally. It takes a quantitative description approach that uses secondary data sourced from the Directorate General of Regional Development, Ministry of Home Affairs, the Republic of Indonesia in 2019–2021. The locus of papers is in five provinces, North Kalimantan, South Kalimantan, Central Kalimantan, West Kalimantan, and East Kalimantan, Indonesia. The data collection and processing consisted of twenty stunting convergence coverage referring to regulations in Indonesia. The analysis used is an integrated framework based on five dimensions. Management based on an integrated framework in a regional-based system for stunting convergence can be a solution to accelerating stunting reduction. This paper provides an option to accelerate the handling of stunting through the Integration of Service Governance-Based Systems in Districts/Cities, considering the achievements in the last three years that have not been maximally carried out in every district/city in five provinces in Kalimantan, Indonesia. This study explains that the local government needs to socialize and disseminate the commitment to stunting reduction results to reaffirm commitment and encourage all parties to actively contribute to integrated stunting reduction efforts. This paper has limitations in the implementation of dimensions that can develop in a context that is correlated with several perspectives, such as regional planning, budgetary capacity, and regional capacity.

1. Introduction

Stunting is commonly defined as a failure to grow in children under the age of five owing to chronic malnutrition, particularly in the first 1000 days of life, which impacts brain growth and development [1]. In addition, stunted children are more likely to develop chronic illnesses as adults. Multiple publications discuss the effects of stunting and malnutrition on economic development and other factors, such as [2,3,4,5,6]. There is strong evidence that poor childhood nutrition, as assessed by stunting or height-for-age, is associated with lower adult income [7]. In [8]’s paper, moreover, it has been estimated that for every percentage point rise in the prevalence of child stunting, GDP per capita in poor nations falls by 0.4%. This was developed by [9] based on the findings of a study on 137 developing nations, which concluded that the cost of inaction is high in terms of the future revenue lost to economies in the developing world [10,11], children’s long-term health and wellbeing as they transition into adulthood. The majority of the variation in child nutrition is attributable to household economics, maternal body mass index, and education [12]. Improved economic growth may have a good impact on the lives of children from wealthy homes, but not those from low-income families [13]. The approach in the papers in [14] and [15] describes the relationship between the factors of economic growth, stunting, and other factors. Several research studies chose the exemplar countries by taking into account both quantitative information (such as the annual rates of stunting change in relation to economic growth and the size of the country’s population) and qualitative insights (e.g., logistics of country work, political stability) [16,17]. As a result, it is crucial to take action to accelerate the decline in stunting [18] by promoting the potential benefits of tailoring centrally launched initiatives to the state’s performance and incorporating co-production into the existing nutrition and health policy framework. To accelerate stunting reduction more equitably [19], food and health system initiatives must be coordinated [19]. In a more complex scope [20], according to a study [21], socially, economically, politically, and emotionally disadvantaged children were not associated with anthropometric and clinical symptoms of malnutrition or delays in physical development.

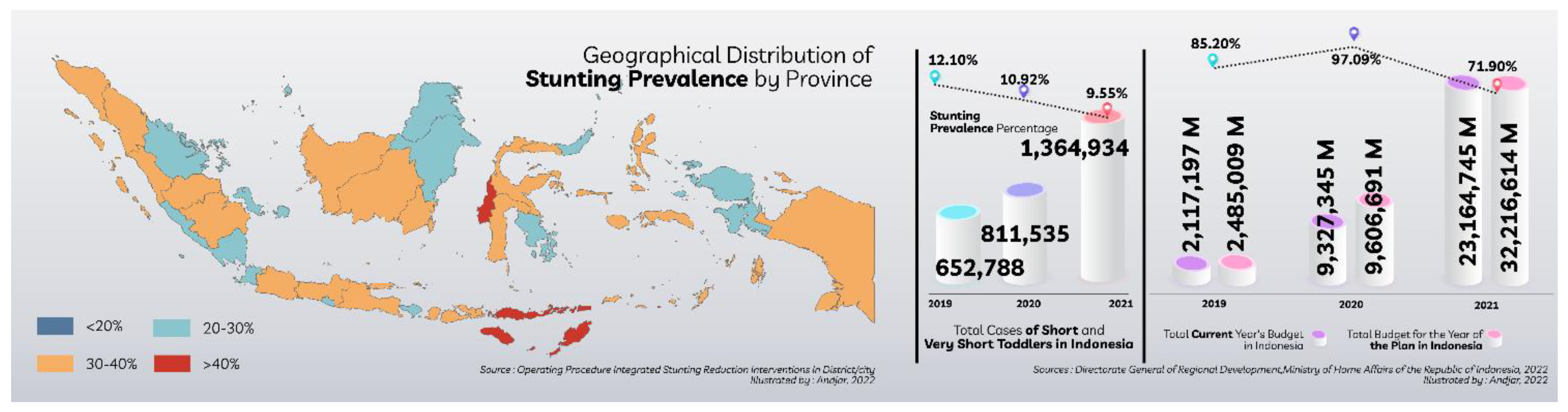

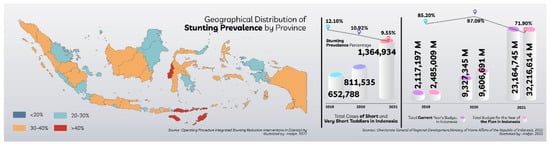

The National Strategy [22] for the acceleration of stunting reduction in 2018–2024 specifies that initiatives to accelerate stunting prevention are implemented in all districts/cities in phases. The Ministry of National Development Planning/National Development Planning Agency determines annually the expansion phases and priority districts and cities, which are described in the Government Work Plan. Several processes include the designation of priority districts and cities to accelerate stunting prevention. In the first phase of 2018, the government prioritized the implementation of interventions in 100 districts and cities. In the second phase of the intervention’s execution in 2019, 160 districts and cities were added. In the third phase (2020–2023), all districts and cities will be gradually included in the activities [22]. Based on the 2018 Basic Health Research mentioned in the Operating Procedure for Integrated Stunting Reduction Interventions In District/city (Figure 1), as many as two provinces have stunting prevalence above 40%, which is very high; eighteen provinces have stunting prevalence between 30–40% which is quite high. DKI Jakarta Province has a stunting prevalence below 20%, which is classified as medium and low. In addition to stunting, the prevalence of wasting in several provinces is also very high, which is above 10%. This indicates a large number of cases of acute malnutrition, with a very high risk of death, which is ten times greater than normal children [22]. Meanwhile, from 2019 to 2021, in the dashboard for accelerating stunting decline nationally, the quantity of stunting shows an increasing condition, although there is a decrease in the percentage comparison. The total budget disbursed by the state in the context of accelerating stunting reduction is also increasing when comparing the total budget for 2019–2021.

Figure 1.

Geographical distribution of stunting prevalence by province; stunting prevalence percentage, total cases of short and very short toddlers, national budget for stunting in 2019–2021.

Stunting has garnered a variety of scientific perspectives. Poverty reduction, women’s empowerment, public health programs focusing on water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH), increasing acceptability, and increased coverage and quality of child and maternal health services are interventions that could improve children’s growth in these two areas [23]. In addition, the government and policymakers need to take long-term steps to fix a number of social and environmental problems that are linked to chronic undernutrition, with a focus on urban slum areas [24]. There is a framework for policies addressing stunting throughout childhood, with emphasis on the requirement for clarity on a single definition of stunting in older children and adolescents in order to streamline monitoring activities [25,26]. Leroy and Frongillo [26] encourage donors, program planners, and researchers to think carefully about the results of nutrition and to plan programs and research that directly target those results.

In one study [27], wawamum (a daily 50-g supplement of fortified chickpea paste) is effective in reducing the risk of stunting, wasting, and anemia among children aged 6 to 23 months. To improve nutrition and health, this strategy should be scaled up in the most food-insecure areas and households with a high prevalence of stunting. By addressing several interdependent factors that prevent children from thriving in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), the One Health strategy may uncover new approaches to combating child stunting, and coordinated interventions between the human health, animal health, and environmental health sectors may have a synergistic effect on stunting reduction [28]. In order to close achievement gaps, priority should be given to strengthening strategies for reducing malnutrition in vulnerable areas as well as those directly affecting EVC [29]. Cultural communication interventions can help stop stunting by getting religious leaders to talk about nutrition on the pulpit and in church programs. This way, more people will know about how to stop malnutrition [30] and how to prevent it [30]. Concerned organizations should prioritize addressing the issue of stunting by improving maternal education, promoting girl education, improving household economic status, promoting context-specific child feeding practices, improving maternal nutrition education, counseling, sanitation, and hygiene practices [31].

However, it should be noted that stunting management should be accompanied by an integrated system framework for its regional management from the perspective of sustainable regional capacity management. There is currently no regionally-integrated research explaining the central government’s program to reduce stunting rates in Indonesia. Based on this occurrence, there is a research gap that must be filled by new findings derived from existing regional data. This paper aims to contribute to the regional system integration framework approach and support the acceleration of stunting reduction at the national level. A framework comprised of leadership and personnel is required; analysis of health for decision-making and tools for stunting are still incomplete; digital health is still conducted with a sectorial approach; and open government must be implemented proportionally. A scalable, dynamic regional framework has not been integrated with health information readiness.

2. Research Design

The methods of quantitative description were based on secondary data collected by the Directorate General of Regional Development, Ministry of Home Affairs, Republic of Indonesia, for the years 2019–2021. The paper concentrates on five Kalimantan provinces (Indonesia): north, south, central, west, and east.

2.1. Data Collection

This research made use of a stunting reduction intervention data management system, an effort to manage data from the district or city level down to the village level, which will be used to aid in the execution of other integration actions and the administration of integrated stunting reduction programs and activities. Information on a wide range of indicators, such as the prevalence of stunting and the reach of nutrition-related programs, is stored in the database.

The data management system is part of information resource management, which includes all activities from identifying data needs to collecting and utilizing data, to ensure accurate and up-to-date information. Activities in the data management system will intersect with aspects of district and city policy, use, and support mechanisms, and are inextricably linked to information technology support in data collection and management. The person responsible for improving this data management system is the Development Planning Agency at Sub-National Level (Bappeda). Bappeda asked each related Regional Apparatus Organization (OPD) to map the need for and use of data and provide program/activity data for which they were responsible. This study uses data collected by OPD from several stages and activities (Table 1).

Table 1.

Research data sources.

In our research, we asked each OPD in charge of the program to map the needs and use of data based on who is the user of the data, the types of decisions that need to be supported with data, and the type of data needed. The data requirements are compiled based on the type of intervention and level of government in the area, starting at the village, sub-district, and district/city levels. We, together with the Regency/City Statistics Unit, need to identify which data systems OPD has. Furthermore, the Bappeda and the Regency/City Statistics Unit need to identify what data are available in the system that is related to priority stunting reduction interventions.

2.2. Analysis Techniques

The data collection and processing analyzed consisted of twenty stunting convergence coverage referring to regulations in Indonesia. The coverage is grouped in the perspective of the subjectivity of the paper for analysis of needs, internally consisting of groups of mothers and children and external limitations consisting of family groups and environmental groups on stunting interventions. Explanations are based on Mother’s group code: A.1.–A.5., Children and Young Women group: B.1.–B.6., Group of Family: C.1.–C.3., and Neighborhoods group: D.1.–D.6. The reference in this scope comes from [1] which provides a technical description of efforts to accelerate stunting reduction in Indonesia. The analysis used is an integrated framework based on five dimensions, namely leadership and staff, analysis of stunting, digital data stunting, open government, and stunting information preparedness.

In this study, we designed an objective situation analysis plan according to the needs of the implementation year [32,33]. In the first year, the objective of the situation analysis was to place more emphasis on providing baseline data on the integration of district/city stunting prevention and reduction program interventions. In the second and subsequent years, the situation analysis aims to determine whether there is an improvement in the situation following the implementation of the stunting prevention and reduction program as a basis for formulating recommendations for corrective action planning.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Intervention for Stunting Coverages in Kalimantan

In summary, ref. [1] explains that the problem of early childhood stunting will have a short-term effect on the quality of human resources (HR), producing growth failure, cognitive and motor development hurdles, non-optimal body size and physical fitness, and metabolic disorders. Long-term exposure produces irreversible changes in the structure and function of nerves and brain cells, as well as a decline in the ability to retain information from an early age, which will have a negative impact on adult productivity. In addition, malnutrition causes growth abnormalities (shortness or thinning) and raises the risk of noncommunicable diseases such as diabetes, hypertension, coronary heart disease, and stroke. Stunting toddlers contribute to 1.5 million (15%) deaths of children under five in the world and cause 55 million disability-adjusted life years (DALYs), i.e., the annual loss of healthy life spans [1]. Efforts to reduce stunting are carried out through two types of interventions: specific nutrition interventions to address direct causes and sensitive nutrition interventions to address indirect causes. In addition to addressing direct and indirect causes, supporting prerequisites such as political and policy commitment to implementation, government, and cross-sectoral involvement, and implementation capacity are necessary. The primary target indicators for the integrated stunting reduction intervention are: (1) the prevalence of stunting in children under five; (2) the percentage of babies with low birth weight; (3) the prevalence of malnutrition (underweight) in children under five; (4) the prevalence of wasting (thin) children under five; (5) the percentage of infants aged less than six months who are exclusively breastfed; (6) the prevalence of anemia in pregnant women and adolescent girls; and (7) the prevalence of diarrhea [1]. This indicator objective is then examined with respect to the location of five provisions on the island of Kalimantan, beginning with a brief description of each province [1].

Approximately three-quarters of the southern portion of the island of Kalimantan belongs to Indonesia, along with the Malaysian states of Sabah and Sarawak and the small Sultanate of Brunei. The Indonesian province of Kalimantan consists of five provinces. First, East Kalimantan encompasses a land area of 127,267.52 km2 and a marine management area of 25,656 km2 between 113°44′ east longitude and 119°00′ east longitude and between 2°33′ north latitude and 2°25′ south latitude. This province fosters ten regencies or cities, namely West Kutai, Kutai Kartanegara, East Kutai, Berau, North Paser Penajam, Mahakam Ulu, Balikpapan, Samarinda, and Bontang. West Kalimantan’s geographical coordinates are 2°05′ north latitude, 3°05′ south latitude, and 108°30′–114°10′ east longitude. West Kalimantan is 147,307 km2 in size.

This province fosters fourteen regencies or cities, namely Sambas, Bengkayang, Landak, Mempawah, Sanggau, Ketapang, Sintang, Kapuas Hulu, Sekadau, Melawi, North Kayong, Kubu Raya, Pontianak, and Singkawang. Third, Central Kalimantan Province, located between 111° east longitude and 116° east longitude and between 0°45′ north latitude and 3°30′ south latitude, is the second-largest province in Indonesia in terms of land area. This province covers fourteen regencies or cities, including West Kotawaringin, East Kotawaringin, Kapuas, South Barito, North Barito, Sukamara, Lamandau, Seruyan, Katingan, Pulang Pisau, Gunung Mas, East Barito, Murung Raya, and Palangka Raya. South Kalimantan Province is geographically located between 1°21′49″ and 1°10′14″ south latitude and 114° 19′33″ east longitude and 116° 33′28″ east longitude, with a total area of 37,377.53 km2 (6.98% of the island of Kalimantan). There are thirteen districts or cities in this province, consisting of Tanah Laut, Kotabaru, Banjar, Barito Kuala, Tapin, Hulu Sungai Selatan, Hulu Sungai Tengah, Hulu Sungai Utara, Tabalong, Tanah Bumbu, Balangan, Banjarmasin, and Banjarbaru. The North Kalimantan Province is located between 114°35′22″ and 118°03′00″ east longitude and 1°21′36″ and 4°24′55″ north latitude. Malinau, Bulungan, Tana Tidung, Nunukan, and Tarakan are the five regencies or cities of the province on the island of Kalimantan, with the fewest number of them compared to other provinces.

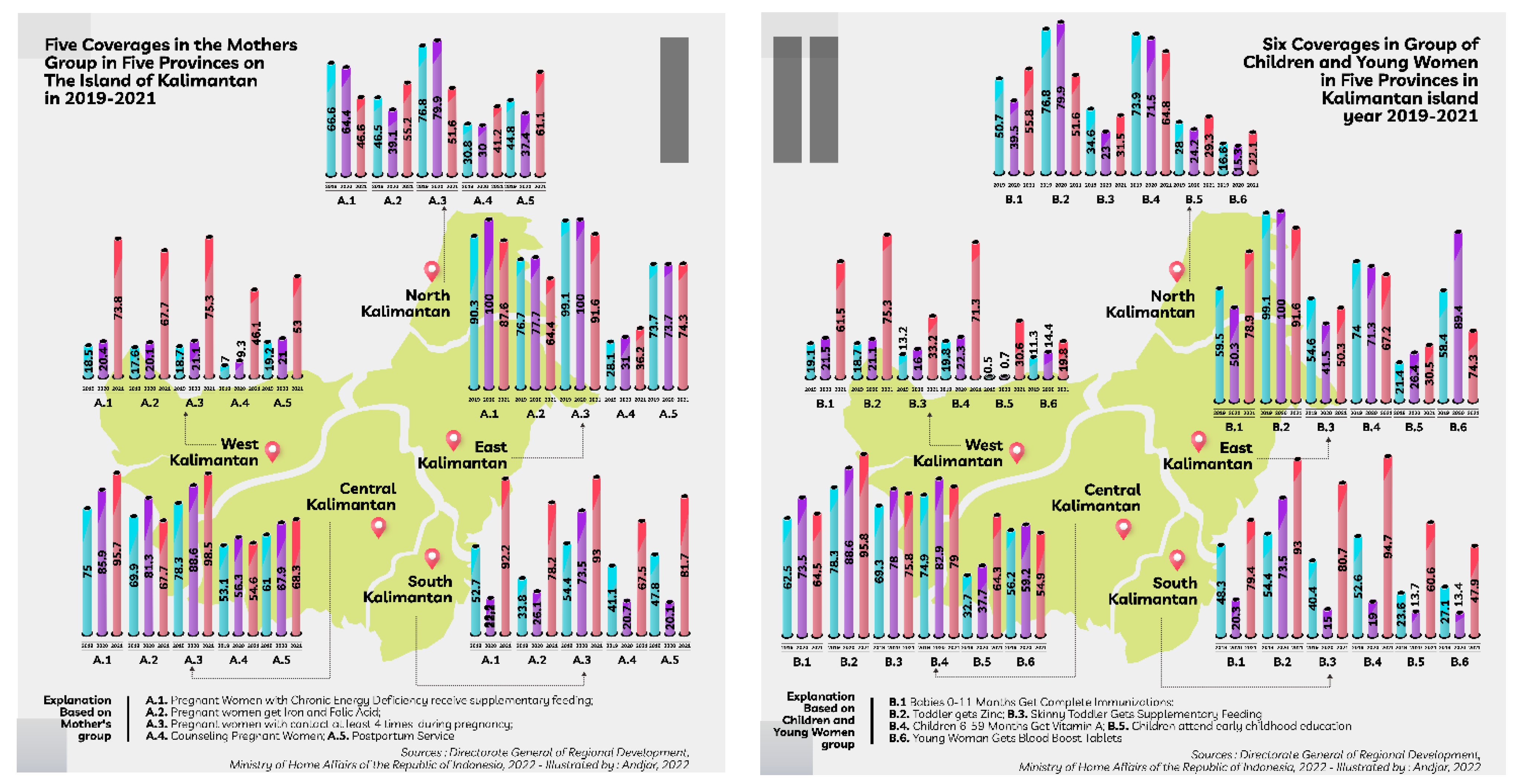

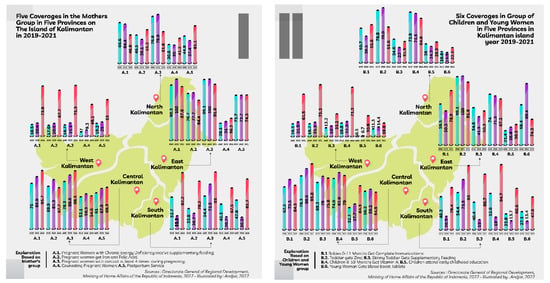

Handling the decline in stunting in five provinces in three consecutive years, from 2019 to 2021, has experienced dynamics that can be described in the maternal coverage group by presenting data on A.1. Pregnant Women with Chronic Energy Deficiency receive supplementary feeding; A.2. Pregnant women get Iron and Folic Acid; A.3. Pregnant women with contact at least four times during pregnancy; A.4. Counseling Pregnant Women; A.5. Postpartum Service. Coverage group of children and adolescent girls by presenting data on Babies 0–11 Months Get Complete Immunizations; B.2. Toddler gets Zinc; B.3. Skinny Toddler Gets Supplementary Feeding; B.4. Children 6–59 Months Get Vitamin A; B.5. Children attend early childhood education; B.6. Young Woman Gets Blood Boost Tablets, in the following two figures. The five coverages in the mother group showed different results in each province, East Kalimantan Province being the province with the lowest coverage in the first two years (2019 and 2020) compared to the other four provinces on the island of Kalimantan. The next group in this paper is assumed to be the group that influences the subject of the acceleration of stunting reduction externally consisting of family groups and environmental groups.

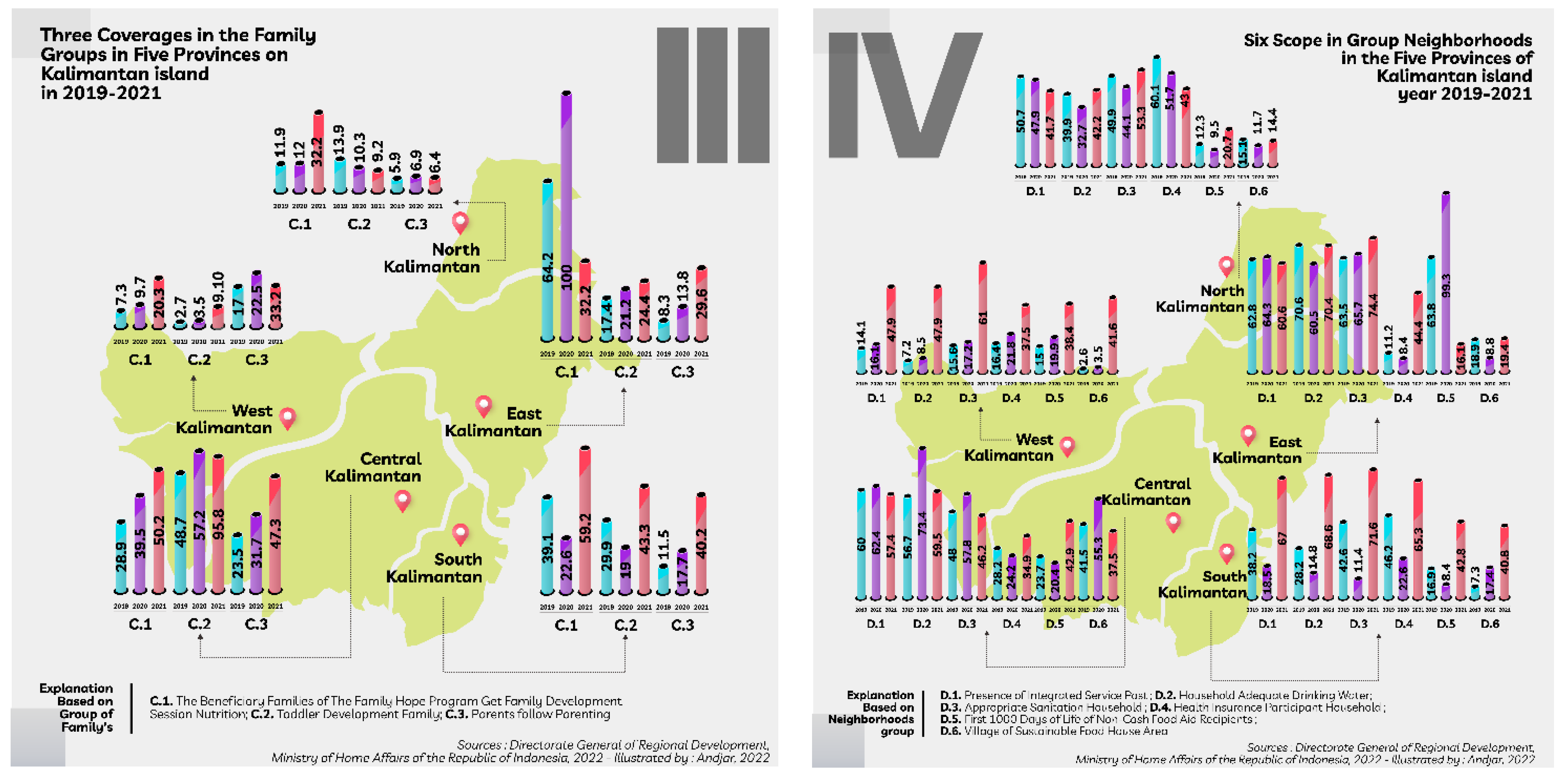

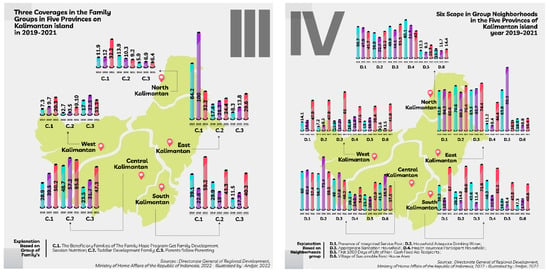

Explanation Based on Group of Family: C.1. The Beneficiary Families of The Family Hope Program Get Family Development Session Nutrition; C.2. Toddler Development Family; C.3. Parents follow Parenting. Explanation Based on Neighborhoods group; D.1. Presence of Integrated Service Post; D.2. Household Adequate Drinking Water; D.3. Appropriate Sanitation Household; D.4. Health Insurance Participant Household; D.5. First 1000 Days of Life of Non-Cash Food Aid Recipients; D.6. Village of Sustainable Food House Area. In Figure 2 and Figure 3, East Kalimantan Province has the lowest achievement score compared to the other four provinces. The description of data collection that has been divided into four groups, in general, shows that a joint effort is still needed by involving leadership commitments that can manage HR to analyze valid stunting data, then presented in digital form that is open so that it can be accessed by relevant stakeholder and has readiness in continuous sustainable data management. This paper seeks to synergize the government’s efforts that have been carried out in eight actions to accelerate stunting reduction.

Figure 2.

Internal intervention for mother, children, and young women in five provinces in Kalimantan Island 2019–2021.

Figure 3.

External intervention for family and neighborhoods in the five provinces of Kalimantan Island 2019–2021.

At this time, there are 20 indicators to measure the performance of stunting. The 20 indicators are targeted for achievement in several OPDs, including 11 indicators for programs in the health sector; 1 indicator for the Office of Women’s Empowerment, Child Protection, Population Control, and Family Planning (P3P2KB); 1 more indicator at the Office of Food Security; 2 indicators at the Office of Employment General Affairs, Spatial Planning, and Land Affairs (PUPRP); 2 indicators at the Office of Education and Culture; and 3 indicators at the Office of Social Affairs. 1. Pregnant women who receive additional feeding recovery and have chronic energy deficiency are covered; 2. Coverage for pregnant women who take at least 90 iron-folic acid blood Supplement Tablets while they are pregnant; 3. Coverage of underweight toddlers who receive additional feeding; 4. Coverage of attendance at integrated healthcare center (ratio of attendance to total target); 5. Coverage of contact at least 4 times during pregnancy; 6. Coverage of children 6–59 months who received Vitamin A; 7. Coverage of infants 0–11 months who receive complete basic immunization; 8. Coverage of toddlers with diarrhea who received zinc sulfate; 9. Coverage young women get blood Supplement Tablets; 10. Coverage of nivas mother’s Services; 11. Coverage of classes for pregnant women (mothers attending nutrition and health counselling); 12. Coverage of families participating in toddler family development; 13. Coverage of households using proper drinking water sources; 14. Coverage of households using proper sanitation; 15. Coverage of parents who attended parenting classes; 16. Coverage of children aged 2–6 years registered (students) in early childhood education; 17. Coverage of households participating in National Health Insurance; 18. Coverage of hope family program who received nutrition and health family development session; 19. Family coverage of 1000 first day of life poor groups as non-cash food aid recipients; 20. Village coverage implementing sustainable food house area.

In the evaluation results from [34], the acceleration of stunting reduction is carried out in 20 indicators grouped into 8 actions. The grouping of 8 actions is a step to accelerate the implementation of government programs with each description as follows: 1. The first action consists of 1.1. Analysis for identification of priority locations; 1.2. Analysis to identify interventions that require priority treatment; 1.3. Analysis of constraints in service management; and 1.4. Recommended situation analysis results. 2. The second action consists of 2.1. The substance of the activity plan; 2.2. The progress of the implementation of the activity plan in the current year; and 2.3. Integration of the activity plan into the next year’s stakeholder work plan. 3. The third action consists of 3.1. Active participation of regional leaders and stakeholders in stunting consultations; 3.2. Stunting discussion agreement/commitment; and 3.3. Publication/socialization of stunting consultations by the media. 4. The fourth action consists of 4.1. The substance of the regulation on the role of the village in reducing stunting; and 4.2. Coverage of villages that received socialization of regulations regarding participation. 5. The fifth action consists of 5.1. Coverage of villages that have human development cadres; and 5.2. Analysis to identify interventions that require priority treatment. 6. The sixth action consists of 6.1. Dea certainty with the certainty of operational cost support; and 6.2. Districts/Cities follow up on data that will be prioritized for improvement. 7. The seventh act consists of 7.1. Districts/Cities have plans to improve their data management system based on the results of the assessment; and 7.2. Districts/Cities carry out an analysis of the results of reducing stunting data. 8. The eighth act consists of 8.1. Districts/Cities publish the results of the latest stunting data analysis; and 8.2. Districts/Cities conduct performance reviews. The contribution of this paper is analyzing the eight actions to develop a framework that has a cycle based on objects and subjects to accelerate stunting reduction. The contribution of this paper is carried out in an integrated governance perspective using the results of the analysis of eight actions. Governance is structured in an integrated governance framework for districts/cities with a continuous cycle based on objects and subjects described in Figure 2 and Figure 3.

Figure 2 and Figure 3 refer to the report on the results of the stunting assessment from (the Directorate General of Regional Development, 2022), in East Kalimantan Province, two regions performed in the Most Inspirational and Most Innovative category, namely Kutai Kartanegara Regency, and the Most Replicative is North Penajam Paser Regency. West Kalimantan Province, Sintang Regency achieved a decent score in stunting handling, then Central Kalimantan Province has three regions that have reported the results of stunting reduction, namely, East Kotawaringin, Barito East, and Kapuas. Then, the Province of South Kalimantan has three regions with performance predicates, the most inspiring is the North Hulu Sungai Regency, the most replicative is the Tapin Regency, and the most innovative is the North Hulu Sungai Regency. Meanwhile, for North Kalimantan Province, two regencies performed in the Most Inspirational and Most Innovative category, Malinau Regency and Nunukan Regency.

The condition of the five provinces on the island of Kalimantan in 2019 shows that management governance is not optimal in accelerating stunting reduction. This paper argues that the cycle needs to be managed sustainably starting from leadership and staff handling, analyzing stunting data in an orderly manner, utilizing stunting data in digital form, disclosing valid and sustainable data, and readiness in integrated governance. The readiness of the leadership and staff in responding to the acceleration of stunting reduction is a necessary initial indicator. The readiness of HR provides speed in classifying stunting subjects and analyzing the validity of the data that has been collected. Barriers to stunting management in digital form are obstacles to achieving stunting goals and targets. Disclosure of valid data in governance provides opportunities for stakeholder participation in accelerating stunting reduction. The use of valid data with ongoing readiness involving relevant stakeholders is a supporting indicator in programs and activities that will be the next reference. Governance involving these indicators can encourage other districts/cities in each province within the island of Kalimantan to have the same capacity to accelerate stunting reduction.

3.2. System Integration Based on Regional Service Governance

Leadership and staff are important dimensions in the governance of accelerating stunting reduction with arguments that provide an understanding of the position of this dimension. Integrating policy requires explicit leadership of the centralized [35]. Some of the conditions that make this possible are the professional and cultural skills of the staff, their ability to lead and their commitment, the compatibility of the different systems, and the funding for health care and support for well-being [36,37]. This form of communication between leaders and subordinates can accelerate governance as stated in [38], this huddle results in more open and active conversations with unit leaders and the ability to take the appropriate actions at the appropriate time. The Co-Lead intervention was co-designed by frontline healthcare staff and management based on evidence for collective leadership and teamwork in healthcare [39]. It is also based on the real-world experiences, needs, and priorities of frontline healthcare staff and management [39]. As a future goal, it is important to find and fill leadership knowledge gaps in order to improve the job satisfaction of health professionals and, in turn, the quality indicators [40] of healthcare [40]. A valuable starting point is to explore the factors driving change and the shift to more collective ways of working observed in response to COVID-19 [41]. From the standpoint of health care personnel, there is heterogeneity, indicating that efforts to reduce adverse effects must be planned and implemented in specific contexts [42]. Leadership in healthcare reform needs to be in line with the strategy for reform and show collaboration, flexibility, and support for new ideas [43]. It is also emphasized in [44]’s paper that, for information dissemination, effective communication between health officials, institutional leadership, and field staff is crucial. Ethics-based forums, which give people a place to talk about and explore ethical dilemmas without getting into a fight, have been well received and can also serve as a way for managers and leaders to get helpful feedback right away [45]. There were strong links between how staff felt about senior leadership, how well they worked as a team, and whether or not they wanted to leave, and how safe patients felt overall [46]. During the COVID-19 outbreak, leaders in government and healthcare must show strong leadership and support for doctors and their families [47]. Closing the skills and knowledge gap could improve the retention of skilled and knowledgeable healthcare leaders, thereby reducing the costs associated with training and leading to improvements in healthcare delivery [48]. For the mental health of healthcare staff, servant leadership is crucial. Thus, it extends the applicability of the servant leadership concept to the literature on psychology and crisis management [49]. A scientific approach to the role of leadership in building commitment and the role of staff who can manage continuous and sustainable data are important indicators in this paper that contribute to accelerating the reduction of stunting at the research location based on regency and city areas in Indonesia. Due to the decentralization system in Indonesia, the leader is still the sole decision-maker on a regional scale, making this one of the most significant indicators [50,51,52,53].

Based on Table 2 above, the description of the mother group, child group, family group, and environmental group in the paper is based on the availability of serial data from 2019 to 2021. This condition can be interpreted that the data are available, and the previous year’s data analysis process can be used as a basis for the following year. Analysis of previous data will be used as consideration and evaluation material for the programs being implemented. The speed of implementation between provinces is not necessarily the same, so it can be a lesson in the coming year. Therefore, the stunting data analysis phase is the second indicator in this paper. Scientific literature has shown how important analysis is for public health. The precision public health use cases where big data has added value, the types of value that big data may bring, and the risks associated with the use of big data in precision public health efforts are described [54]. The review in [55] paper highlights the lack of national and international research on the role of managers in public health in frontier areas. The topic’s significance and complexity demonstrate the need for research on managers in this field. From another angle [56], important suggestions are made to strengthen the role of veterinarians in public health for the control of zoonotic diseases that are not being paid enough attention to. The article from [57] confirms that an increase in the proportion of public health expenditures reduces the impact of economic indicators on child mortality. Therefore, more attention must be paid to the negative effects of the macroeconomic crisis in order to improve the health of children [58]. Ref. [58] identifies three characteristics of a robust applied public health research community that are required for contributions to the principles: researcher autonomy, sustainable cross-sectoral research capacity, and a critical perspective on the practice-policy interface of research. Then, in [59], the article complements the SPHERE (Social Media and Public Health Epidemic and Response) continuum model in public health. This model illustrates the functions of social media across the continuum of epidemic response, including contagion, vector, surveillance, immunization, disease control, and treatment. A comprehensive set of outcomes pertinent to the evaluation of the health effects of social media. The topic of this paper is public health during the pandemic [60], with the COVID-19 Community Vulnerability Index, a tool that can help identify communities most at risk of contracting COVID-19 based on indicators such as socioeconomic status factors and health care systems. Comics have been used as a vehicle to present science in graphic narratives, harnessing the power of visuals, text, and storytelling in an engaging format. This paper examines the emerging role of comics as a public health tool during the COVID-19 pandemic [61], as well as the supporting research [61]. Papers from [62] standardized training-to-practice timeline highlights the importance of the relationship between medical education and socio-environmental influences on health and public health with seven key recommendations. In the context of the election, the [63] article talks about how important public health is and how important it is for everyone to speak up as a way to improve public health.

Table 2.

Maternal and child health program data in Kalimantan.

Based on Table 3 above, it is known that in every province in Kalimantan, there has been an increase in the overall health program. This result is known from the range and the mean number, which have both increased. A sharp increase occurred in 2021 in all provinces, mainly due to increased public awareness regarding health due to the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 and the government increasing socialization of health programs, especially in the province of Kalimantan, which is projected to become a candidate for Indonesia’s new capital city. Based on the data above, it is known that the increase in the achievement of the health program was accompanied by an increase in the standard deviation, therefore it can be said that equity in these government programs is still not classified as effective when viewed from the mean and standard deviation distances obtained. The government implements supervision and monitoring of this health program online so that it can adjust to the social restrictions currently being implemented by the government [64,65]. According to [66], digital health has been proven to be able to bridge the government’s health program through the equitable distribution of health assistance throughout the province of Kalimantan.

Table 3.

Comparison of health programs by year.

Digital health has grown rapidly globally and its implementation has been carried out in stages. The scientific approach to the role of digitization penetrates all sectors, the health sector has a strategic portion in the digitizing process, including digitizing stunting data. The designed system could serve as a monitoring support model utilizing free and user-friendly data science tools, which are cost-effective alternatives to expensive proprietary business intelligence solutions. Still, the success of decision-making systems depends on investments in human resources, training in business intelligence skills, the organization of the decision-making process, and quality assurance of data production [67]. A framework to bring out actionable knowledge is elaborated in [68]. As the Healthcare Research and Analytics Data Infrastructure Solution (HRADIS) model was [69] used, there was talk about a number of important issues, lessons learned, reflections and suggestions, and things to think about for the future [69]. Then, [70] enhanced understanding of digital behavior, including its conceptualization and measurement, in training programs. The purpose of implementing a business intelligence cost accounting solution is to improve the efficiency of healthcare settings and provide managers with new tools to manage resources and plan for the future [71]. The extraction of knowledge from hospital data with a focus on clinical decision-making was carried out in [72], making it easier for health data to work with each other and push for the creation of national electronic health records [73]. This is corroborated by the article [74] which constructed the business intelligence dashboard using the business intelligence development methodology. It requires treatment to improve its performance. Remaining Useful Life (RUL) prognostics techniques employ Artificial Intelligence (AI) and future research opportunities to investigate monitoring techniques, feature extraction methods, decision-making models, and currently available sensors for the data-driven model [75]. A foundational reference to inform the analysis of specific ethical and regulatory challenges arising from the use of machine learning-based predictive analytics (MLPA) to enhance the efficacy of health care can be found in [76]. The concept of digital health is complemented in [77] article, three business models include: (i) an intermediary model, (ii) a surrogate model, and (iii) a direct-to-consumer model, and we analyze their customer value.

Open Government [78]: to narrow the divide between rural and urban areas, the government must build ICT infrastructure in rural areas and provide citizens with training on how to utilize these infrastructures [79]. In [79], due to a dearth of research on this topic, the current study contributes to the body of knowledge by examining the effect of perceived risk, government support, and perceived usefulness on customers’ intention to use e-wallets during the COVID-19 outbreak. In most countries, services that use online apps, social media, and videos are growing quickly, shedding light on important parts of e-health services [80]. Since telemedicine is a field that is always changing, training for medical professionals, clear rules, and high-quality Internet service systems will go a long way toward making people more open to it [81]. Establishing communication strategies for protracted public health crises, making financial resources available to carry out such strategies, and reducing the digital divide can all contribute to more effective disclosure [78,82]. Ref. [83]’s paper is the first to investigate the adoption of e-government health applications launched by the MOH in South Africa during the COVID-19 pandemic and to provide a theoretical framework for future research work of a comparable scope. Perceived utility has a substantial impact on the adoption of e-government services in the delivery of healthcare services in healthcare institutions [84]. In strengthening the health system and e-government system, according to [85], China’s 6G invention will take China’s institutional structure to the next level. It will also help fight future disasters and the waves of COVID-19 [86] that are expected to hit in the near future. According to [86], during the COVID-19 outbreak, people in charge of public health may use e-government and social media as effective ways to get people to act in ways that protect them [87]. It is recommended that professionals contribute to the modification of the e-health system and the addition of more government regulatory bodies in order to increase adoption. The digital capabilities leverage sustained investment in new digital technology and integrated government platforms and provide a stable base for the COVID-19 emergency response, including sustained access to multiple e-government resources [88]. With the discovery that the pandemic is making the need for digital governance more urgent, the health crisis has pushed the limits of technology, which has become a “magic bullet” for completing economic tasks that are important to national economies on a global [89] scale [89].

3.3. Discussion

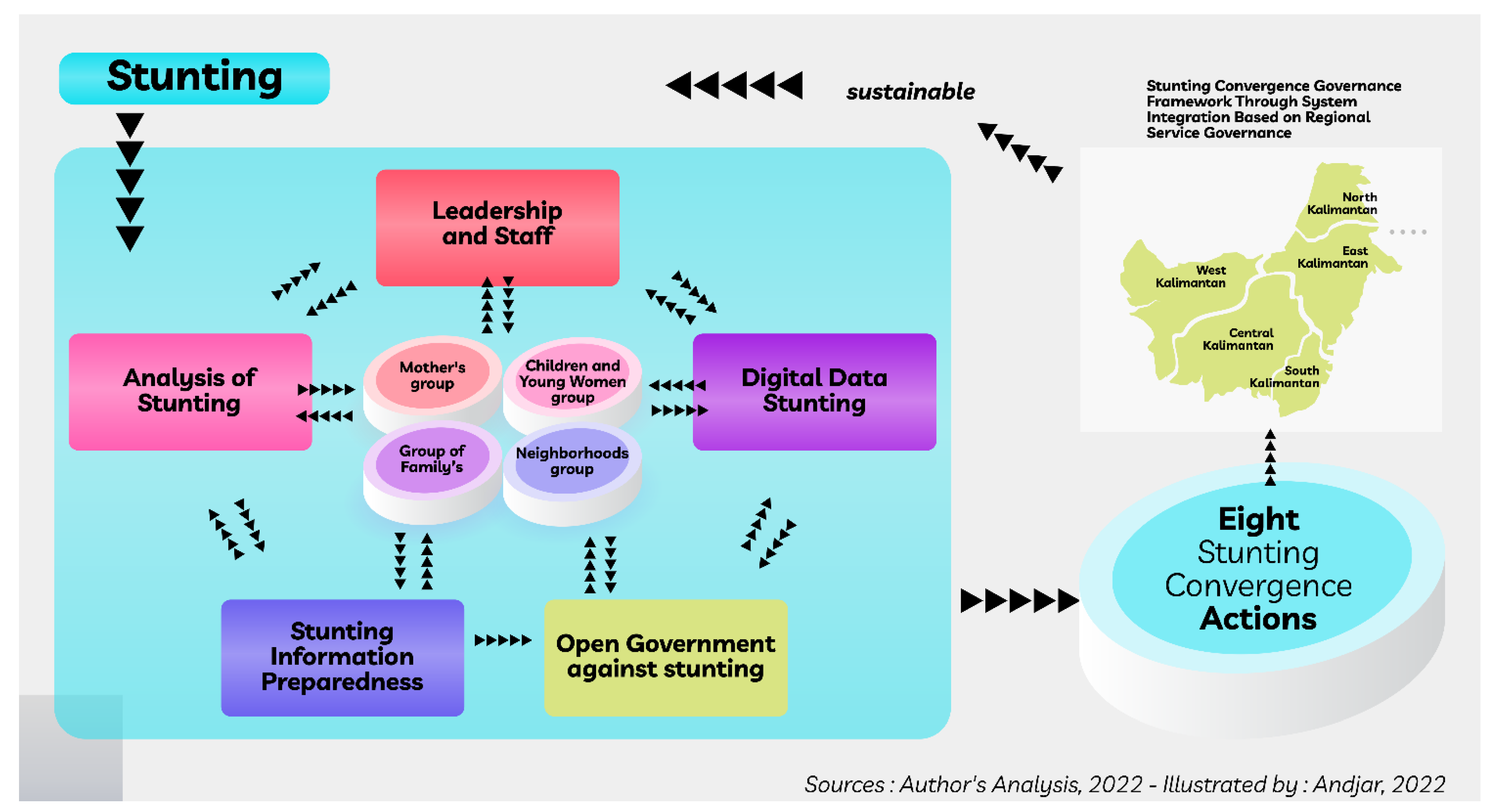

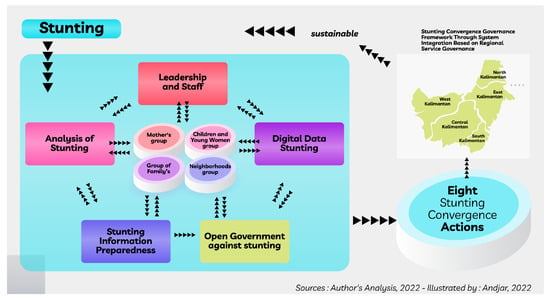

Referring to several scientific approaches that discuss the roles and positions of Leadership and Staff, the process of health analysis, Digital Health, Open Government, and Health Information Preparedness, then with the results of stunting reduction in five provinces in Kalimantan Island, the framework is presented in Figure 4. Leadership and staff; stunting analysis; digitizing stunting data; the readiness of stunting data management then become a single unit that is compiled in a framework based on integrated system governance at the district/city level. The integration system is related to the handling of twenty scopes which have been divided into four groups to fulfill eight actions according to the provisions required by the central government.

Figure 4.

Stunting convergence governance framework through system integration based on regional service governance.

The governance integration as shown in Figure 4 begins with a framework that involves leadership and staff to analyze the existing condition of stunting based on previous data. The results of the stunting analysis are used as digital data that have useful value in program development in the context of accelerating stunting reduction. However, in this development, local government transparency is also needed in encouraging access to relevant stakeholders so that it becomes data that can be used in reducing stunting in the following year. To maintain the continuity of governance integration, Stunting Information Preparedness is needed, because the regional character of the five provinces on the island of Kalimantan has heterogeneity. The integration presented in this paper also narrates the results that can be achieved for each district/city, so that efforts to accelerate stunting reduction are more measurable both in terms of quality and quantity.

The first dimension, leadership and staff, has indicators (1) Leadership and staff awareness and knowledge of Stunting Convergence point: big data, open data; and (2) leadership and staff are committed to a sustainable digital stunting policy, and digitally focused and literate, especially predictive analytics, data management readiness, forecasting. This indicator is equipped with the results to be achieved with tiered boundaries, as follows: (1) Management and staff understand the basics of the Stunting Convergence policy; The Stunting Convergence policy is understood by the leadership and staff gradually internally; (2) The Stunting Convergence policy is understood by leadership and staff to be gradually sustainable internally and externally; (3) Knowledge of the Stunting Convergence policy and digital literacy is evenly distributed among leaders and staff, with evidence of routine application in practice in twenty stunting reduction areas; and (4) Knowledge of the Stunting Convergence policy and digital literacy is evenly distributed among leaders and staff, with evidence of routine application in practice across twenty stunting reduction areas internally and externally at all levels and across sectors. The relevance of this first dimension can refer to the five predefined scopes in twenty stunting coverages, consisting of 3.1. Active participation of regional leaders and stakeholders in stunting consultation; 3.2. Stunting discussion agreement/commitment; 4.1. The substance of regulation on the role of villages in stunting reduction; 5.1. Coverage of villages that have human development cadres; and 7.2. Districts/Cities carry out an analysis of the results of reducing stunting data.

Additionally, the second dimension, the analysis of stunting, includes indicators. Accessibility of essential information and advanced analytical techniques to support real-time clinical, management, policy, and decision-making needs assessments for stunting convergence. This indicator can describe the accomplishments that can be pursued by each district or city in the five provinces on the island of Kalimantan, subject to the limitations described below. (1) Routine statistical analysis is applied to available stunting convergence data to generate reports on the status and outcomes of stunting convergence. Other types of staggered convergence analysis are required for special presentations and projects and are performed ad hoc. Rarely is evidence-informed decision-making integrated into the policy and management culture; (2) there is evidence that Stunting Convergence data and information are routinely used to support policy and management decisions based on mostly descriptive analyses; (3) all critical information to support monitoring of the twenty stunting coverage, management, decision-making of stunting convergence policies is easily accessible, and the public has on-demand access to information products or stunting convergence analysis resources. There is capacity among technical and managerial staff for evidence-based decision-making. Various established health analysis approaches are applied routinely; (4) continued capacity building among technical staff (investment in skills, tools, partnerships) for more advanced approaches to health analysis; and (5) there is annual capacity and budget for training to increase expert capacity among staff conducting routine real-time and clinical stunting analysis, management and policy decision-making based on timely analysis and data for community stunting reduction strategies and activities. As with the first indicator, in the second indicator, there are four stunting coverages which are part of twenty stunting coverages. The four stunting coverages in this second indicator are 1.1. Analysis for identification of priority locations; 1.2. analysis to identify interventions that require priority treatment; 1.4. recommended situation analysis; and 5.2. analysis to identify interventions that require priority treatment.

The third dimension is digital stunting data, which has indicators to provide a description that can be understood by actors in districts/cities in the context of leadership and staff on stunting digital efforts. the required indicators are digital stunting convergence tools are used to transform data collection, and stunting reduction models, improve maternal and child safety, and quality of care, and support the population stunting approach. Stunting reduction care and services are provided virtually. The description of this dimension is narrated in stages so that the government can adopt it, given the limited capacity in districts/cities in five provinces on the island of Kalimantan. The stages that can be narrated at least reach at (1) stunting care delivery and services are largely a manual process. Assess digital technology in stunting including information systems at the district/city level to identify areas for improvement; (2) digitally stunting data such as electronic archives, information systems, and electronic order entry are being implemented with a focus on digitizing manual processes and improving operational efficiency. A roadmap was developed based on the assessment to better integrate digital technology into the existing stunting system, including normative and technical aspects.; (3) digital stunting tool used to change the model of data collection, treatment, improve stunting reduction, or to support a progressively developed approach to stunting in the community; (4) digital stunting tools are used to facilitate targeted communication to individuals to stimulate demand for stunting services/information access and digital stunting interventions to improve decision support/telemedicine mechanisms, and (5) digital stunting management technology enables population stunting management and rapid response to action plans. Citizens are empowered to manage stunting reduction and to proactively engage with stunting reduction service providers. Four scopes can be correlated in this third dimension, consisting of 6.1. village certainty with the certainty of operational cost support; 6.2. regencies/cities follow up on data that will be prioritized for improvement; 7.1. districts/cities have a data management system improvement plan based on the results of the assessment; and 8.2. regencies/cities conduct performance reviews.

The fourth dimension is Open Government, which is the basis for increasing the involvement of relevant stakeholders; this dimension provides space to utilize it with an ethical structure and mutually agreed on rules. Indicators in this dimension, consist of (1) The integration of stunting convergence into e-Government initiatives, including the implementation of standards, applications, and information services to transform transactions between government and the public, businesses, or other organizations in stunting reduction; (2) Stunting convergence e-government is on the institutional agenda (Interaction of citizens with the government); (3) The current focus of e-government is on the level of integration of institutional stunting reduction in e-government initiatives; (4) Integration of public ports specifically for district/city level stunting convergence with local government e-government platforms; and (5) Leadership and staff knowledge, leadership support to advance Open Government policies and initiatives, integrated into institutional policies for handling stunting reduction. The directions to be achieved in the fourth dimension are based on indicators that have been prepared through the integration of stunting management, consisting of (1) Open Government and E-government have been on the stunting convergence institutional agenda, albeit informally; (2) the regency/city government has established an Open Government and E-government strategy, with the stage on strengthening the core IT infrastructure; (3) there is evidence of Open Government and E-government initiatives changing interactions with stakeholders in reducing stunting, and (4) stunting convergence is integrated into Open Government initiatives and e-government platforms. Meanwhile, four coverages in twenty stunting coverages that have relevance in this dimension are 2.1. the substance of the activity plan; 2.2. progress of the implementation of the activity plan in the current year; 2.3. integration of the activity plan into the next year’s stakeholder work plan; and 8.1. districts/cities publish the results of the latest stunting data analysis.

The fifth dimension, Stunting Information Preparedness, provides the function of maintaining the continuity of the information needed in the next action plan, the lack of awareness in managing information also slows down efforts to reduce stunting in the districts/cities in the locus of this paper. The indicators that can be conveyed in this last dimension are: (1) The capacity of the Stunting Convergence information system to operate sustainably requires the development and implementation of continuous operating procedures to ensure access to the right information at the right time in the right format; (2) there is a plan for the restoration of stunting convergence information, an action plan to ensure the functionality of the stunting convergence; (3) main datasets, data backup strategy, stunting convergence information system can support twenty stunting coverages regularly. This indicator is limited by the conditions that can be achieved by stunting information managers at the district/city level in five provinces on the island of Kalimantan, which consist of (1) manual and electronic stunting convergence information systems are still vulnerable, and limited data are available to support stunting reduction action plans; (2) efforts on an evidence-based approach to ensure business continuity in the case of stunting reduction (e.g., SOPs, manual processes). Several key datasets are available to support stunting convergence; (3) the essential stunting convergence information system has been proven to have worked during the implementation of the action plan and will be able to support several functions of the stunting reduction system; and (4) a valid stunting convergence information system that can support the function, during the implementation of the stunting reduction process in a sustainable manner. The four coverages in the twenty stunting coverages that can be linked are 3.3. publication/socialization of stunting consultation by media; 4.2. coverage of villages that have received regulation socialization on participation; 5.1. coverage of villages that have human development cadres; and 5.2. analysis to identify interventions that require priority treatment.

4. Conclusions

The Stunting Convergence Management Framework can be structured from several perspectives by taking into account the character and heterogeneity of the region. This paper provides an option to accelerate the handling of stunting through the Integration of Service Governance-Based Systems in Districts/Cities, considering the achievements in the last three years that have not been maximally carried out in every district/city in five provinces in Kalimantan, Indonesia. Leadership and staff, analysis of stunting, digital data on stunting, open government, and stunting information preparedness are the dimensions described in the paper from the perspective of sustainable management of stunting convergence management. Health information preparedness needs to be managed on an ongoing basis to encourage the use of data. This role has an important portion considering the acceleration of stunting reduction utilizes information as one of the fundamental problem-solving procedures. The public health information management system of primary health care units, which is based on the design of medical and health information, is feature-rich and highly efficient, considerably enhancing the public health of grassroots medical units. In the context of health, attitudes are the primary determinants of continued use of health information systems; habits greatly improve the perception of health professionals, which in turn improves their attitudes toward continued use of health information systems. Then, important components for the continued development of a framework for monitoring the quality of data collection procedures for public health information systems include the data collection environment, data collection training, leadership, and finance. The gathered information could be utilized by health institutions to establish processes that contribute to the nationwide implementation and adoption of health information systems. In the past, the majority of countries lacked standardization and interoperability, provider, and user acceptance, and project financing for the development of large-scale health information systems. The quality of routine data acquired by the health system must be enhanced with prudence; regular triangulation with data from other sources is suggested to alleviate denominator issues, minimize indicator complexity, and align indicators with international definitions.

The results of this study can identify the reports that are considered relevant as input for the implementation of stunting prevention policies and programs in five provinces in Kalimantan. This research can also help OPD and other organizations, such as universities, civil society groups, donor agencies, and international development partners. Information on the mapping of programs/activities, scope and prevalence (number and cases) of stunting is very much needed in the process of analyzing the situation and determining priority locations in each district/city. Mapping programs and activities are done to determine the type and location of their implementation. To assess the scope of program/activity implementation, the scope of both specific and sensitive interventions needs to be studied. While the prevalence distribution (cases and numbers) of stunting is used as a guide in determining stunting-prone locations, this study explains that the local government needs to socialize and disseminate the commitment to stunting reduction results to reaffirm commitment and encourage all parties to actively contribute to integrated stunting reduction efforts. With socialization and dissemination, the community can also carry out social monitoring of the implementation of commitments in an integrated stunting reduction effort in their respective areas. This paper has limitations in the implementation of dimensions that can develop in a context that is correlated with several perspectives, such as regional planning, budgetary capacity, and regional capacity.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.N. and A.P.; methodology, M.F. and B.P.H.; software, W.R. and M.A.A.; validation, N.N. and A.P.; formal analysis, M.A.A.; investigation, A.P.; resources, M.F. and H. (Hartiningsih); data curation, A.P. and H. (Hendrixon); writing—original draft preparation, N.N. and A.P.; writing—review and editing, M.F. and H. (Hendrixon); visualization, B.P.H. and H. (Hartiningsih); supervision, M.F.; project administration, M.F. and A.P.; funding acquisition, A.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Kementerian PPN/Bappenas. Pedoman Pelaksanaan Intervensi Penurunan Stunting Terintegrasi Di Kabupaten/Kota; Kementerian PPN/Bappenas: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- McGovern, M.E.; Krishna, A.; Aguayo, V.M.; Subramanian, S. A review of the evidence linking child stunting to economic outcomes. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2017, 46, 1171–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bevis, L.; Kim, K.; Guerena, D. Soil zinc deficiency and child stunting: Evidence from Nepal. J. Heal. Econ. 2023, 87, 102691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bridgman, G.; von Fintel, D. Stunting, double orphanhood and unequal access to public services in democratic South Africa. Econ. Hum. Biol. 2021, 44, 101076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kofinti, R.E.; Koomson, I.; Paintsil, J.A.; Ameyaw, E.K. Reducing children’s malnutrition by increasing mothers’ health insurance coverage: A focus on stunting and underweight across 32 sub-Saharan African countries. Econ. Model. 2022, 117, 106049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akseer, N.; Tasic, H.; Onah, M.N.; Wigle, J.; Rajakumar, R.; Sanchez-Hernandez, D.; Akuoku, J.; Black, R.E.; Horta, B.L.; Nwuneli, N.; et al. Economic costs of childhood stunting to the private sector in low- and middle-income countries. Eclinicalmedicine 2022, 45, 101320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkins, J.M.; Kim, R.; Krishna, A.; McGovern, M.; Aguayo, V.M.; Subramanian, S. Understanding the association between stunting and child development in low- and middle-income countries: Next steps for research and intervention. Soc. Sci. Med. 2017, 193, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mary, S. How Much Does Economic Growth Contribute to Child Stunting Reductions? Economies 2018, 6, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fawzi, M.C.S.; Andrews, K.G.; Fink, G.; Danaei, G.; McCoy, D.C.; Sudfeld, C.R.; Peet, E.D.; Cho, J.C.; Liu, Y.; Finlay, J.E.; et al. Lifetime economic impact of the burden of childhood stunting attributable to maternal psychosocial risk factors in 137 low/middle-income countries. BMJ Glob. Health 2019, 4, e001144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharbi, N.S.; AlGhanmi, A.S.; Fahlevi, M. Adoption of Health Mobile Apps during the COVID-19 Lockdown: A Health Belief Model Approach. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agbo, C.C.; Mahmoud, Q.H.; Eklund, J.M. Blockchain technology in healthcare: A systematic review. Healthcare 2019, 7, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, P.; Rammohan, A.; Gwozdz, W.; Sousa-Poza, A. Changes in Child Nutrition in India: A Decomposition Approach. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaya, S.; Uthman, O.A.; Kunnuji, M.; Navaneetham, K.; Akinyemi, J.O.; Kananura, R.M.; Adjiwanou, V.; Adetokunboh, O.; Bishwajit, G. Does economic growth reduce childhood stunting? A multicountry analysis of 89 Demographic and Health Surveys in sub-Saharan Africa. BMJ Glob. Health 2020, 5, e002042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akseer, N.; Vaivada, T.; Rothschild, O.; Ho, K.; Bhutta, Z.A. Understanding multifactorial drivers of child stunting reduction in Exemplar countries: A mixed-methods approach. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 112, 792S–805S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhutta, Z.A.; Akseer, N.; Keats, E.C.; Vaivada, T.; Baker, S.; Horton, S.E.; Katz, J.; Menon, P.; Piwoz, E.; Shekar, M.; et al. How countries can reduce child stunting at scale: Lessons from exemplar countries. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 112, 894S–904S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasetyo, A.; Gartika, D.; Hartopo, A.; Harwijayanti, B.P.; Sukamsi, S.; Fahlevi, M. Capacity Development of Local Service Organizations Through Regional Innovation in Papua, Indonesia After the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasetyo, A.; Harwijayanti, B.P.; Ikhwan, M.N.; Maknun, M.L.; Fahlevi, M. Interaction of Internal and External Organizations in Encouraging Community Innovation. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, K.; Dwivedi, L.K. Disparity in childhood stunting in India: Relative importance of community-level nutrition and sanitary practices. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0238364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baye, K.; Laillou, A.; Chitweke, S. Socio-Economic Inequalities in Child Stunting Reduction in Sub-Saharan Africa. Nutrients 2020, 12, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheffler, C.; Hermanussen, M.; Soegianto, S.; Homalessy, A.; Touw, S.; Angi, S.; Ariyani, Q.; Suryanto, T.; Matulessy, G.; Fransiskus, T.; et al. Stunting as a Synonym of Social Disadvantage and Poor Parental Education. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadhani, I.D.; Latifah, L.; Prasetyo, A.; Khairunnisa, M.; Wardhani, Y.F.; Yunitawati, D.; Fahlevi, M. Infodemiology on diet and weight loss behavior before and during COVID-19 pandemic in Indonesia: Implication for public health promotion. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tim Nasional Percepatan Penanggulangan Kemiskinan. Strategi Nasional Percepatan Pencegahan Anak Kerdil (Stunting) Periode 2018–2024; Edisi Kedu; Sekretariat Wakil Presiden Republik Indonesia: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2019.

- Rabaoarisoa, C.R.; Rakotoarison, R.L.; Rakotonirainy, N.H.; Mangahasimbola, R.T.; Randrianarisoa, A.B.; Jambou, R.; Vigan-Womas, I.; Piola, P.; Randremanana, R.V. The importance of public health, poverty reduction programs and women’s empowerment in the reduction of child stunting in rural areas of Moramanga and Morondava, Madagascar. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0186493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, M.M.; Sanin, K.I.; Mahfuz, M.; Ahmed, A.M.S.; Mondal, D.; Haque, R.; Ahmed, T. Risk factors of stunting among children living in an urban slum of Bangladesh: Findings of a prospective cohort study. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Partap, U.; Young, E.H.; Allotey, P.; Sandhu, M.S.; Reidpath, D.D. Characterisation and correlates of stunting among Malaysian children and adolescents aged 6–19 years. Glob. Health Epidemiology Genom. 2019, 4, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leroy, J.L.; Frongillo, E.A. Perspective: What Does Stunting Really Mean? A Critical Review of the Evidence. Adv. Nutr. Int. Rev. J. 2019, 10, 196–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, G.N.; Kureishy, S.; Ariff, S.; Rizvi, A.; Sajid, M.; Garzon, C.; Khan, A.A.; De Pee, S.; Soofi, S.B.; Bhutta, Z.A. Effect of lipid-based nutrient supplement—Medium quantity on reduction of stunting in children 6-23 months of age in Sindh, Pakistan: A cluster randomized controlled trial. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0237210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gharpure, R.; Mor, S.M.; Viney, M.; Hodobo, T.; Lello, J.; Siwila, J.; Dube, K.; Robertson, R.C.; Mutasa, K.; Berger, C.N.; et al. A One Health Approach to Child Stunting: Evidence and Research Agenda. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2021, 104, 1620–1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Vásquez, A.; Pisfil-Benites, N.; Vargas-Fernández, R.; Azañedo, D. Nutritional status and effective verbal communication in Peruvian children: A secondary analysis of the 2019 Demographic and Health Survey. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0246542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marni, M.; Abdullah, A.Z.; Thaha, R.M.; Hidayanty, H.; Sirajuddin, S.; Razak, A.; Stang, S.; Liliweri, A. Cultural Communication Strategies of Behavioral Changes in Accelerating of Stunting Prevention: A Systematic Review. Open Access Maced. J. Med Sci. 2021, 9, 447–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muche, A.; Gezie, L.D.; Baraki, A.G.-E.; Amsalu, E.T. Predictors of stunting among children age 6–59 months in Ethiopia using Bayesian multi-level analysis. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prahiawan, W.; Fahlevi, M.; Juliana, J.; Purba, J.T.; Tarigan, S.A. The role of e-satisfaction, e-word of mouth and e-trust on repurchase intention of online shop. Int. J. Data Netw. Sci. 2021, 5, 593–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purwanto, A.; Wirawati, S.M.; Arthawati, S.N.; Radyawanto, A.S.; Rusdianto, B.; Haris, M.; Kartika, H.; Rabathi, S.R.; Fahlevi, M.; Abidin, R.Z.; et al. Lean Six Sigma Model for Pharmacy Manufacturing: Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow. Syst. Rev. Pharm. 2020, 11, 304–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Directorate General of Regional Development Dashboard Monitoring 8 Aksi Konvergensi. Available online: https://aksi.bangda.kemendagri.go.id/web/in/main/home (accessed on 15 March 2022).

- Poole, N.; Echavez, C.; Rowland, D. Are agriculture and nutrition policies and practice coherent? Stakeholder evidence from Afghanistan. Food Secur. 2018, 10, 1577–1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCalman, J.; Benveniste, T.; Wenitong, M.; Saunders, V.; Hunter, E. “It’s all about relationships”: The place of boarding schools in promoting and managing health and wellbeing of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander secondary school students. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 113, 104954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasetyo, A.; Raharjo, T.W.; Rinawati, H.S.; Eko, B.R.; Wahyudiyono, S.N.; Fahlevi, M.; Aljuaid, M.; Heidler, P. Determination of Critical Factors for Success in Business Incubators and Startups in East Java. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldawood, F.; Kazzaz, Y.; AlShehri, A.; Alali, H.; Al-Surimi, K. Enhancing teamwork communication and patient safety responsiveness in a paediatric intensive care unit using the daily safety huddle tool. BMJ Open Qual. 2020, 9, e000753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Brún, A.; Anjara, S.; Cunningham, U.; Khurshid, Z.; Macdonald, S.; O’Donovan, R.; Rogers, L.; McAuliffe, E. The Collective Leadership for Safety Culture (Co-Lead) Team Intervention to Promote Teamwork and Patient Safety. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Specchia, M.; Cozzolino, M.; Carini, E.; Di Pilla, A.; Galletti, C.; Ricciardi, W.; Damiani, G. Leadership Styles and Nurses’ Job Satisfaction. Results of a Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjara, S.; Fox, R.; Rogers, L.; De Brún, A.; McAuliffe, E. Teamworking in Healthcare during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Mixed-Method Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huhtala, M.; Geurts, S.; Mauno, S.; Feldt, T. Intensified job demands in healthcare and their consequences for employee well-being and patient satisfaction: A multilevel approach. J. Adv. Nurs. 2021, 77, 3718–3732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, D.; de Vries, J.; Comiskey, C.M. Leadership and Community Healthcare Reform: A Study Using the Competing Values Framework (CVF). Leadersh. Health Serv. 2021, 34, 485–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Goy, R.; Sng, B.; Lew, E. Considerations and strategies in the organisation of obstetric anaesthesia care during the 2019 COVID-19 outbreak in Singapore. Int. J. Obstet. Anesthesia 2020, 43, 114–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drewett, G.P.; Gibney, G.; Ko, D. Practical ethical challenges and moral distress among staff in a hospital COVID-19 screening service. Intern. Med. J. 2021, 51, 1513–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaheer, S.; Ginsburg, L.; Wong, H.J.; Thomson, K.; Bain, L.; Wulffhart, Z. Acute care nurses’ perceptions of leadership, teamwork, turnover intention and patient safety—A mixed methods study. BMC Nurs. 2021, 20, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galbraith, N.; Boyda, D.; McFeeters, D.; Hassan, T. The mental health of doctors during the COVID-19 pandemic. BJPsych Bull. 2020, 45, 93–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abraham, T.H.; Stewart, G.L.; Solimeo, S.L. The importance of soft skills development in a hard data world: Learning from interviews with healthcare leaders. BMC Med Educ. 2021, 21, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zada, M.; Zada, S.; Khan, J.; Saeed, I.; Zhang, Y.J.; Vega-Muñoz, A.; Salazar-Sepúlveda, G. Does Servant Leadership Control Psychological Distress in Crisis? Moderation and Mediation Mechanism. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2022, 15, 607–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paranata, A. The miracle of anti-corruption efforts and regional fiscal independence in plugging budget leakage: Evidence from western and eastern Indonesia. Heliyon 2022, 8, e11153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanafi, Y.; Taufiq, A.; Saefi, M.; Ikhsan, M.A.; Diyana, T.N.; Thoriquttyas, T.; Anam, F.K. The new identity of Indonesian Islamic boarding schools in the “new normal”: The education leadership response to COVID-19. Heliyon 2021, 7, e06549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setyowati, A.B.; Quist, J. Contested transition? Exploring the politics and process of regional energy planning in Indonesia. Energy Policy 2022, 165, 112980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desky, H.; Mukhtasar, M.I.; Ariesa, Y.; Dewi, I.; Fahlevi, M.; Abdi, M.; Noviantoro, R.; Purwanto, A. Did trilogy leadership style, organizational citizenship behaviour (OCB) and organizational commitment (OCO) influence financial performance? Evid. Pharm. Ind. 2020, 11, 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolley, S. Big Data’s Role in Precision Public Health. Front. Public Health 2018, 6, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hortelan, M.D.S.; Almeida, M.D.L.D.; Fumincelli, L.; Zilly, A.; Nihei, O.K.; Peres, A.M.; Sobrinho, R.A.; Pereira, P.E. Papel do gestor de saúde pública em região de fronteira: Scoping review. Acta Paul. de Enferm. 2019, 32, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elelu, N.; Aiyedun, J.O.; Mohammed, I.G.; Oludairo, O.; Odetokun, I.A.; Mohammed, K.M.; Bale, J.O.; Nuru, S. Neglected zoonotic diseases in Nigeria: Role of the public health veterinarian. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2019, 32, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tejada, C.A.O.; Triaca, L.M.; Liermann, N.H.; Ewerling, F.; Costa, J.C. Crises econômicas, mortalidade de crianças e o papel protetor do gasto público em saúde. Ciênc. Saúde Coletiva 2019, 24, 4395–4404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaren, L.; Braitstein, P.; Buckeridge, D.; Contandriopoulos, D.; Creatore, M.I.; Faulkner, G.; Hammond, D.; Hoffman, S.J.; Kestens, Y.; Leatherdale, S.; et al. Why public health matters today and tomorrow: The role of applied public health research. Can. J. Public Health 2019, 110, 317–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chittamuru, D.; Ramírez, A.S. From “Infodemics” to Health Promotion: A Novel Framework for the Role of Social Media in Public Health. Am. J. Public Health 2020, 110, 1393–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melvin, S.C.; Wiggins, C.; Burse, N.; Thompson, E.; Monger, M. The Role of Public Health in COVID-19 Emergency Response Efforts From a Rural Health Perspective. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2020, 17, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kearns, C.; Kearns, N. The role of comics in public health communication during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Vis. Commun. Med. 2020, 43, 139–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, R.; Hawkins, M.; Ulrich, T.; Gatlin, G.; Mabry, G.; Mishra, C. The Evolving Role of Public Health in Medical Education. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehlinger, E.P.; Nevarez, C.R. Safe and Accessible Voting: The Role of Public Health. Am. J. Public Health 2021, 111, 45–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golinelli, D.; Boetto, E.; Carullo, G.; Nuzzolese, A.G.; Landini, M.P.; Fantini, M.P. Adoption of digital technologies in health care during the COVID-19 pandemic: Systematic review of early scientific literature. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e22280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melia, R.; Francis, K.; Hickey, E.; Bogue, J.; Duggan, J.; O’Sullivan, M.; Young, K. Mobile health technology interventions for suicide prevention: Systematic review. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2020, 8, e12516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alharbi, N.S.; Alsubki, N.; Altamimi, S.R.; Alonazi, W.; Fahlevi, M. COVID-19 Mobile Apps in Saudi Arabia: Systematic Identification, Evaluation, and Features Assessment. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 803677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Housbane, S.; Khoubila, A.; Ajbal, K.; Agoub, M.; Battas, O.; Othmani, M.B. Real-Time Monitoring System to Manage Mental Healthcare Emergency Unit. Heal. Informatics Res. 2020, 26, 344–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, A.; Karim, M. Designing a Model to Study Data Mining in Distributed Environment. J. Data Anal. Inf. Process. 2021, 9, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozaydin, B.; Zengul, F.; Oner, N.; Feldman, S.S. Healthcare Research and Analytics Data Infrastructure Solution: A Data Warehouse for Health Services Research. J. Med Internet Res. 2020, 22, e18579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Medina, A.J.; Galván-Sánchez, I.; Fernández-Monroy, M. Applying artificial intelligence to explore sexual cyberbullying behaviour. Heliyon 2020, 6, e03218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azevedo, J.; Duarte, J.; Santos, M.F. Implementing a business intelligence cost accounting solution in a healthcare setting. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2022, 198, 329–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abreu, J.; Guimarães, T.; Abelha, A.; Santos, M.F. Business Analytics Components for Public Health Institution—Clinical Decision Area. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2022, 198, 335–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruson, D. Big Data, artificial intelligence and laboratory medicine: Time for integration. Adv. Lab. Med. Av. Med. Lab. 2021, 2, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wibowo, R.P.; Anggraeni, W.; Arifiyah, T.; Riksakomara, E.; Samopa, F.; Pujiadi, P.; Zehroh, S.A.; Lestari, N.A. Business Intelligence Development in Distributed Information Systems to Visualized Predicting and Give Recommendation for Handling Dengue Hemorrhagic Fever. J. Inf. Syst. Eng. Bus. Intell. 2020, 6, 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayyad, S.; Kumar, S.; Bongale, A.; Kamat, P.; Patil, S.; Kotecha, K. Data-Driven Remaining Useful Life Estimation for Milling Process: Sensors, Algorithms, Datasets, and Future Directions. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 110255–110286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichol, A.A.; Batten, J.N.; Halley, M.C.; Axelrod, J.K.; Sankar, P.L.; Cho, M.K. A Typology of Existing Machine Learning–Based Predictive Analytic Tools Focused on Reducing Costs and Improving Quality in Health Care: Systematic Search and Content Analysis. J. Med Internet Res. 2021, 23, e26391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikuchi, S.; Kadama, K.; Sengoku, S. Characteristics and Classification of Technology Sector Companies in Digital Health for Diabetes. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blom, P.; Uwizeyimana, D. Assessing the Effectiveness of e-Government and e-Governance in South Africa: During National Lockdown 2020. Res. World Econ. 2020, 11, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aji, H.M.; Berakon, I.; Husin, M. COVID-19 and e-wallet usage intention: A multigroup analysis between Indonesia and Malaysia. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2020, 7, 1804181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wynn, R.; Gabarron, E.; Johnsen, J.-A.K.; Traver, V. Special Issue on E-Health Services. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahi, P.K.; Mishra, D.; Singh, T. Medical Education Amid the COVID-19 Pandemic. Indian Pediatr. 2020, 57, 652–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padeiro, M.; Bueno-Larraz, B.; Freitas, Â. Local governments’ use of social media during the COVID-19 pandemic: The case of Portugal. Gov. Inf. Q. 2021, 38, 101620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamufleh, D.; Alshamari, A.S.; Alsobhi, A.S.; Ezzi, H.H.; Alruhaili, W.S. Exploring Public Attitudes toward E-Government Health Applications Used During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Evidence from Saudi Arabia. Comput. Inf. Sci. 2021, 14, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ironbar, A.E.; Angioha, P.U.; Uno, I.A.; Ada, J.A.; Ibioro, F.E. Drivers of the Adoption of E-Government Services in the deliverance of healthcare services in Federal Health Institutions. ARRUS J. Eng. Technol. 2021, 1, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, H.S.M.; Xu, X.; Sun, C. China health technology and stringency containment measures during COVID-19 pandemic: A discussion of first and second wave of COVID-19. Heal. Technol. 2021, 11, 405–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dawi, N.M.; Namazi, H.; Hwang, H.J.; Ismail, S.; Maresova, P.; Krejcar, O. Attitude Toward Protective Behavior Engagement During COVID-19 Pandemic in Malaysia: The Role of E-government and Social Media. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 609716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]