Parents’ Response to Children’s Performance and Children’s Self-Esteem: Parent–Child Relationship and Friendship Quality as Mediators

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Parents’ Response to Children’s Performance and Children’s Self-Esteem

1.2. Mediating Role of Parent–Child Relationship and Friendship Quality

1.2.1. The Mediating Role of Parent–Child Relationship

1.2.2. The Mediating Role of Friendship Quality

1.3. Parent–Child Relationship and Friendship Quality as Sequential Mediators

1.4. The Present Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Parents’ Response to Children’s Performance

2.2.2. Parent–Child Relationship

2.2.3. Friendship Quality

2.2.4. Self-Esteem

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Common Method Bias Test

3.2. Preliminary Analyses

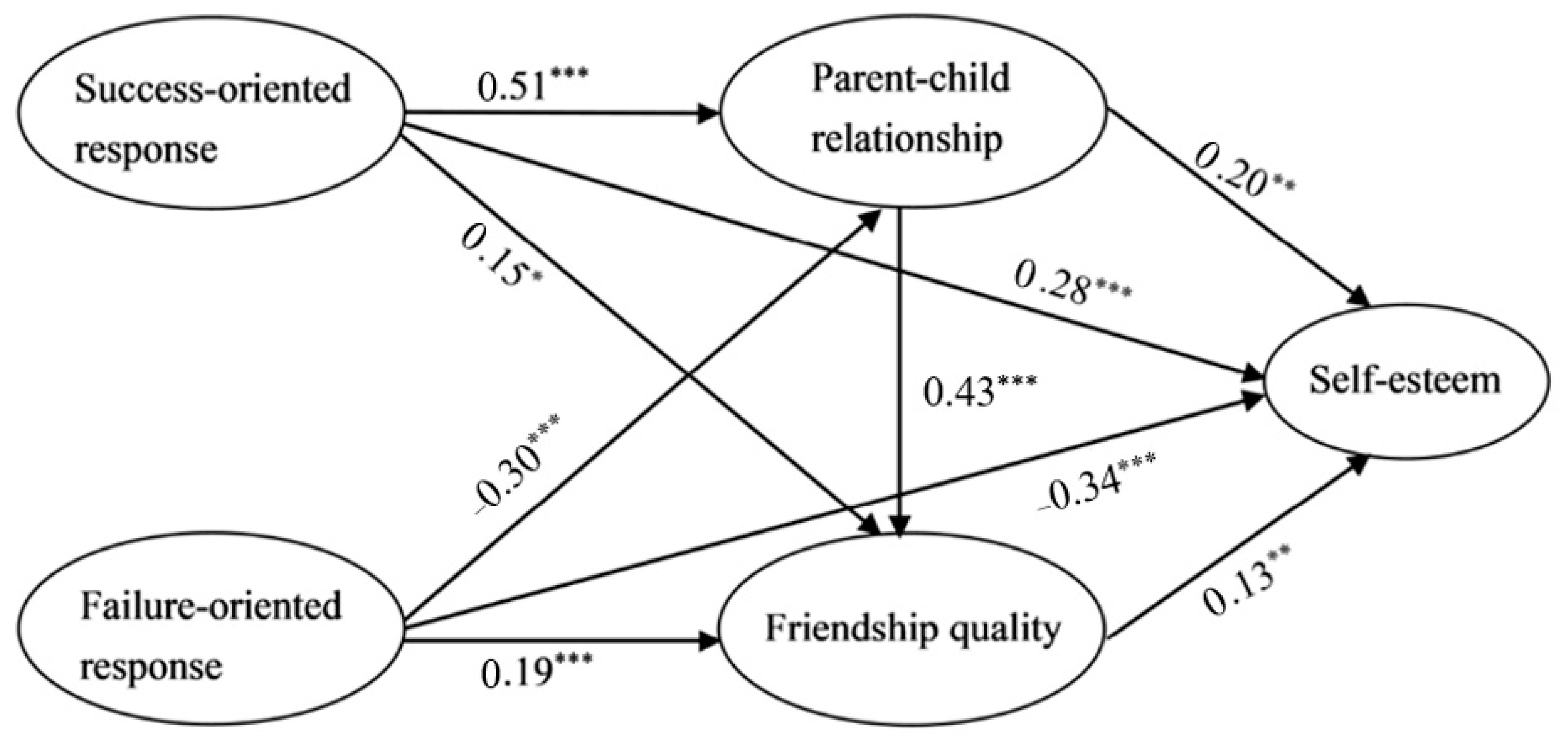

3.3. Mediation Model with Parent–Child Relationship and Friendship Quality

3.3.1. Test of Measurement Model

3.3.2. Significance Test of Mediating Effect

4. Discussion

4.1. Parents’ Response to Children’s Performance and Children’s Self-Esteem

4.2. The Mediating Role of Parent–Child Relationship

4.3. The Mediating Role of Friendship Quality

4.4. The Serial Mediation Role of Parent–Child Relationship and Friendship Quality

5. Conclusions, Limitations, and Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Harter, S. Developmental perspectives on the self-system. In Handbook of Child Psychology; Mussen, P.H., Ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1983; Volume 4, pp. 275–386. [Google Scholar]

- Orth, U.; Robins, R.W. The development of self-esteem. Curr. Psychol. 2014, 23, 381–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Babore, A.; Trumello, C.; Candelori, C.; Paciello, M.; Cerniglia, L. Depressive symptoms, self-esteem and perceived parent-child relationships in early adolescence. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lerner, R.M.; Lerner, J.V.; Murry, V.M.; Smith, E.P.; Bowers, E.P.; Geldhof, G.J.; Buckingham, M.H. Positive youth development in 2020: Theory, research, programs, and the promotion of social justice. J. Res. Adolesc. 2021, 31, 1114–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pomerantz, E.M.; Ng, J.; Ng, F.F. The role of culture in parents’ responses to children’s performance: The case of the West and East Asia. In Psychological Perspectives on Praise; Brummelman, E., Ed.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2020; pp. 140–147. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, J.; Sze, I.N.L.; Ng, F.F.Y.; Pomerantz, E.M. Parents’ responses to their children’s performance: A process examination in the United States and China. Dev. Psychol. 2020, 56, 2331–2344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, F.F.Y.; Pomerantz, E.M.; Lam, S.F.; Deng, C. The role of mothers’ child-based worth in their affective responses to children’s performance. Child Dev. 2019, 90, e165–e181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Olson, K.R.; Dweck, C.S. A blueprint for social cognitive development. Perspec. Psychol. Sci. 2008, 3, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, J.; Ng, F.F.; Pomerantz, E.M. Mothers’ goals influence their responses to children’s performance: An experimental study in the United States and Hong Kong. Child Dev. 2021, 92, 2317–2334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, J.; Xiong, Y.; Qu, Y.; Cheung, C.; Ng, F.F.Y.; Wang, M.; Pomerantz, E.M. Implications of Chinese and American mothers’ goals for children’s emotional distress. Dev. Psychol. 2019, 55, 2616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, F.F.; Pomerantz, E.M.; Lam, S.F. European American and Chinese parents’ responses to children’s success and failure: Implications for children’s responses. Dev. Psychol. 2007, 43, 1239–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomerantz, E.M.; Ng, F.F.Y.; Cheung, C.S.S.; Qu, Y. Raising happy children who succeed in school: Lessons from China and the United States. Child Dev. Perspect. 2014, 8, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, N.; Levitt, M.J. The social ecology of middle childhood: Family support, friendship quality and self-esteem. Fam. Relat. 1998, 47, 315–321. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/585262 (accessed on 3 January 2020). [CrossRef]

- Bulanda, R.E.; Majumdar, D. Perceived parental-child relations and adolescent self-esteem. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2009, 18, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raboteg-Saric, Z.; Sakic, M. Relations of parenting styles and friendship quality to self-esteem, life satisfaction and happiness in adolescents. Appl. Res. Qual. Life. 2014, 9, 749–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinohara, R.; Sugisawa, Y.; Tong, L.; Tanaka, E.; Watanabe, T.; Onda, Y.; Kawashima, Y.; Hirano, M.; Tomisaki, E.; Mochizuki, Y.; et al. Influence of maternal praise on developmental trajectories of early childhood social competence. Creat. Educ. 2012, 3, 533–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hart, J.R.; Coates, E.E.; Smith-Bynum, M.A. Parenting style and parent-child relationship quality in African American mother-adolescent dyads. Parenting 2019, 19, 318–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aloia, L.S.; Warren, R. Quality parent-child relationships: The role of parenting style and online relational maintenance behaviors. Commun. Rep. 2019, 32, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Zhang, D.; Chen, Y.; Yu, C.; Zhen, S.; Zhang, W. Parental psychological control, psychological need satisfaction, and non-suicidal self-injury among Chinese adolescents: The moderating effect of sensation seeking. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2022, 136, 106417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grogan-Kaylor, A.; Burlaka, V.; Ma, J.; Lee, S.; Castillo, B.; Churakova, I. Predictors of parental use of corporal punishment in Ukraine. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2018, 88, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, J.; Benson, M. Parent-child relations and adolescent functioning: Self-esteem, substance abuse, and delinquency. Adolescence. 2004, 39, 519–530. [Google Scholar]

- Steele, E.H.; McKinney, C. Emerging adult psychological problems and parenting style: Moderation by parent-child relationship quality. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2019, 146, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yu, C.; Zhen, S.; Zhang, W. Parent-Adolescent Communication, School Engagement, and Internet Addiction among Chinese Adolescents: The Moderating Effect of Rejection Sensitivity. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2021, 18, 3542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Ma, C.; Gu, C.; Zuo, B. What matters most to the left-behind children’s life satisfaction and school engagement: Parent or grandparent? J. Child Fam. Stud. 2018, 27, 2481–2490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, J.; Padilla, B. Self-esteem and family challenge: An investigation of their effects on achievement. J. Youth Adolesc. 2003, 32, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, W.; Liu, R.D.; Ding, Y.; Oei, T.P.; Zhen, R.; Jiang, S. Parents’ phubbing and problematic mobile phone use: The roles of the parent-child relationship and children’s self-esteem. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2019, 22, 779–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shenaar-Golan, V.; Goldberg, A. Subjective well-being, parent-adolescent relationship, and perceived parenting style among Israeli adolescents involved in a gap-year volunteering service. J. Youth Stud. 2019, 22, 1068–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuczynski, L.; Parkin, C.M. Agency and bidirectionality in socialization: Interactions, transactions, and relational dialectics. In Handbook of Socialization: Theory and Research; Grusec, J.E., Hastings, P.D., Eds.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 259–283. [Google Scholar]

- Batool, S.S.; Lewis, C.A. Does positive parenting predict prosocial behavior and friendship quality among adolescents? Emotional intelligence as a mediator. Curr. Psychol. 2020, 41, 1997–2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stearns, J.A.; Godley, J.; Veugelers, P.J.; Ekwaru, J.P.; Bastian, K.; Wu, B.; Spence, J.C. Associations of friendship and children’s physical activity during and outside of school: A social network study. SSM-Popul. Health. 2019, 7, 100308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, D.; Hart, C.H.; Cheah, C.S.L.; Balkaya, M.; Vu, K.T.T.; Liu, J. Chinese American Children’s Temperamental Shyness and Responses to Peer Victimization as Moderated by Maternal Praise. J. Fam. Psychol. 2020, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maltais, C.; Bouffard, T.; Vezeau, C.; Dussault, F. Does parental concern about their child performance matter? Transactional links with the student’s motivation and development of self-directed learning behaviors. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 2021, 24, 1003–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keefe, K.; Berndt, T.J. Relations of friendship quality to self-esteem in early adolescence. J. Early Adolesc. 1996, 16, 110–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonopoulou, K.; Chaidemenou, A.; Kouvava, S. Peer acceptance and friendships among primary school pupils: Associations with loneliness, self-esteem and school engagement. Educ. Psychol. Pract. 2019, 35, 339–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meter, D.J.; Card, N.A. Stability of children’s and adolescents’ friendships: A meta-analytic review. Merrill-Palmer Q. 2016, 62, 252–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maunder, R.; Monks, C.P. Friendships in middle childhood: Links to peer and school identification, and general self-worth. Br. J. Dev. Psychol. 2019, 37, 211–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Georgiou, N.; Stavrinides, P.; Georgiou, S. Parenting and children’s adjustment problems: The mediating role of self-esteem and peer relations. Emot. Behav. Diffic. 2016, 21, 433–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikulincer, M.; Shaver, P.R.; Pereg, D. Attachment theory and affect regulation: The dynamics, development, and cognitive consequences of attachment-related strategies. Motiv. Emot. 2003, 27, 77–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Chui, H.; Chung, M.C. The effect of parent-adolescent relationship quality on deviant peer affiliation: The mediating role of self-control and friendship quality. J. Soc. Pers. Relat. 2020, 37, 2714–2736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, K.H.; Oh, W.; Menzer, M.; Ellison, K. Dyadic relationships from a cross-cultural perspective: Parent–child relationships and friendship. In Socioemotional Development in the Cultural Context; Chen, X., Rubin, K.J., Eds.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 208–237. [Google Scholar]

- Beyers, W.; Seiffge-Krenke, I. Are friends and romantic partners the “best medicine”? How the quality of other close relations mediates the impact of changing family relationships on adjustment. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2007, 31, 559–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stright, A.D.; Herr, M.Y.; Neitzel, C. Maternal scaffolding of children’s problem solving and children’s adjustment in kindergarten: Hmong families in the United States. J. Educ. Psychol. 2009, 101, 207–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchanan, C.M.; Maccoby, E.E.; Dornbusch, S.M. Caught between parents: Adolescents’ experience in divorced homes. Child Dev. 1991, 62, 1008–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.X.; Fang, X.Y.; Zhou, Z.K.; Zhang, J.T.; Deng, L.Y. Perceived parent-adolescent relationship, perceived parental online behaviors and pathological internet use among adolescents: Gender-specific differences. PLoS ONE. 2013, 8, e75642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hu, J.; Ai, H. Self-esteem mediates the effect of the parent-adolescent relationship on depression. J. Health Psychol. 2016, 21, 897–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q.X.; Fang, X.Y.; Yan, N.; Zhou, Z.K.; Yuan, X.J.; Lan, J.; Liu, C.Y. Multi-family group therapy for adolescent Internet addiction: Exploring the underlying mechanisms. Addict. Behav. 2015, 42, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, M.; Chan, K.L. Parental absence, child victimization, and psychological well-being in rural China. Child Abus. Negl. 2016, 59, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parker, J.G.; Asher, S.R. Friendship and friendship quality in middle childhood: Links with peer group acceptance and feelings of loneliness and social dissatisfaction. Dev. Psychol. 1993, 29, 611–621. Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1993-44976-001 (accessed on 3 January 2020). [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Sun, X.; Zhao, D.; Yeh, H. The test of the mediator variable between peer relationship and loneliness in middle childhood. Acta Psychol. Sin. 2005, 37, 776–783. Available online: http://journal.psych.ac.cn/xlxb/CN/Y2005/V37/I06/776 (accessed on 3 January 2020). (In Chinese).

- Wang, Y.; Hawk, S.T.; Tang, Y.; Schlegel, K.; Zou, H. Characteristics of emotion recognition ability among primary school children: Relationships with peer status and friendship quality. Child Indic. Res. 2019, 12, 1369–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harter, S. Manual for the Self-Perception Profile for Children (Revision of the Perceived Competence Scale for Children); University of Denver: Denver, CO, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Muris, P.; Meesters, C.; Fijen, P. The self-perception profile for children: Further evidence for its factor structure, reliability, and validity. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2003, 35, 1791–1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.C.; Liu, J.S.; Li, D.; Sang, B. Psychometric properties of Chinese version of Harter’s Self-Perception Profile for Children. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 2014, 22, 251–255. [Google Scholar]

- Chiou, H.H.; Hsieh, L.P. Comparative study of children’s self-concepts and parenting stress between families of children with epilepsy and asthma. J. Nurs. Res. 2008, 16, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthén, L.K.; Muthén, B.O. Mplus User’s Guide, 7th ed.; Muthén and Muthén: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Wothke, W. Longitudinal and multigroup modeling with missing data. In Modeling Longitudinal and Multiple Group Data: Practical Issues, Applied Approaches, and Specific Examples; Little, T.D., Schnabel, K.U., Baumert, J., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 2000; pp. 205–224. [Google Scholar]

- Erceg-Hurn, D.M.; Mirosevich, V.M. Modern robust statistical methods: An easy way to maximize the accuracy and power of your research. Am. Psychol. 2008, 63, 591–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chang, S.J.; Van Witteloostuijn, A.; Eden, L. From the editors: Common method variance in international business research. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2010, 41, 178–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. On happiness and human potentials: A review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 141–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vansteenkiste, M.; Ryan, R.M.; Soenens, B. Basic psychological need theory: Advancements, critical themes, and future directions. Motiv. Emot. 2020, 44, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Berger, L.M.; Font, S.A. The role of the family and family-centered programs and policies. Future Child. 2015, 25, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagwell, C.L.; Schmidt, M.E. The friendship quality of overtly and relationally victimized children. Merrill-Palmer Q. 2011, 57, 158–185. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/23097542 (accessed on 3 January 2020). [CrossRef]

- Youngblade, L.M.; Belsky, J. Parent-child antecedents of 5-year-olds’ close friendships: A longitudinal analysis. Dev. Psychol. 1992, 28, 700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuligni, A.J.; Eccles, J.S. Perceived parent-child relationships and early adolescents’ orientation toward peers. Dev. Psychol. 1993, 29, 622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngai, S.S.Y.; Cheung, C.K.; To, S.M.; Liu, Y.; Song, H.Y. Parent-child relationships, friendship networks, and developmental outcomes of economically disadvantaged youth in Hong Kong. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2013, 35, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.M.; Park, H. Effects of self-esteem improvement program on self-esteem and peer attachment in elementary school children with observed problematic behaviors. Asian Nurs. Res. 2015, 9, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Variables | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Gender | 0.54 | 0.50 | 1 | ||||||

| 2 Grade | 4.54 | 1.16 | 0.04 | 1 | |||||

| 2 Success-oriented response | 2.99 | 0.95 | 0.02 | −0.04 | 1 | ||||

| 3 Failure-oriented response | 2.57 | 0.95 | 0.06 | 0.07 * | 0.07 | 1 | |||

| 4 Parent–child relationship | 3.34 | 0.96 | −0.03 | −0.11 ** | 0.37 ** | −0.22 ** | 1 | ||

| 5 Friendship quality | 3.72 | 0.79 | −0.16 ** | 0.12 ** | 0.29 ** | 0.08 * | 0.34 ** | 1 | |

| 6 Self-esteem | 2.73 | 0.62 | 0.06 | −0.02 | 0.30 ** | −0.28 ** | 0.35 ** | 0.21 ** | 1 |

| Indirect Effect Values | SE | 95% Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total indirect effects of SOR | 0.148 | 0.031 | [0.086, 0.211] |

| SOR→PCR→SEM | 0.101 | 0.032 | [0.038, 0.165] |

| SOR→FQ→SEM | 0.019 | 0.010 | [−0.002, 0.039] |

| SOR→PCR→FQ→SEM | 0.028 | 0.012 | [0.005, 0.051] |

| Total indirect effects of FOR | −0.052 | 0.024 | [−0.098, −0.006] |

| FOR→PCR→SEM | −0.060 | 0.021 | [−0.100, −0.019] |

| FOR→FQ→SEM | 0.025 | 0.012 | [0.001, 0.048] |

| FOR→PCR→FQ→SEM | −0.017 | 0.008 | [−0.031, −0.002] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, W.; Tan, F.; Zhou, Z.; Xue, Y.; Gu, C.; Xu, X. Parents’ Response to Children’s Performance and Children’s Self-Esteem: Parent–Child Relationship and Friendship Quality as Mediators. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6012. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19106012

Li W, Tan F, Zhou Z, Xue Y, Gu C, Xu X. Parents’ Response to Children’s Performance and Children’s Self-Esteem: Parent–Child Relationship and Friendship Quality as Mediators. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(10):6012. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19106012

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Weina, Fenge Tan, Zongkui Zhou, Yukang Xue, Chuanhua Gu, and Xizheng Xu. 2022. "Parents’ Response to Children’s Performance and Children’s Self-Esteem: Parent–Child Relationship and Friendship Quality as Mediators" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 10: 6012. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19106012

APA StyleLi, W., Tan, F., Zhou, Z., Xue, Y., Gu, C., & Xu, X. (2022). Parents’ Response to Children’s Performance and Children’s Self-Esteem: Parent–Child Relationship and Friendship Quality as Mediators. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(10), 6012. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19106012