Ghanaian SMEs Amidst the COVID-19 Pandemic: Evaluating the Influence of Entrepreneurial Orientation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials

2.1. Theoretical Framework

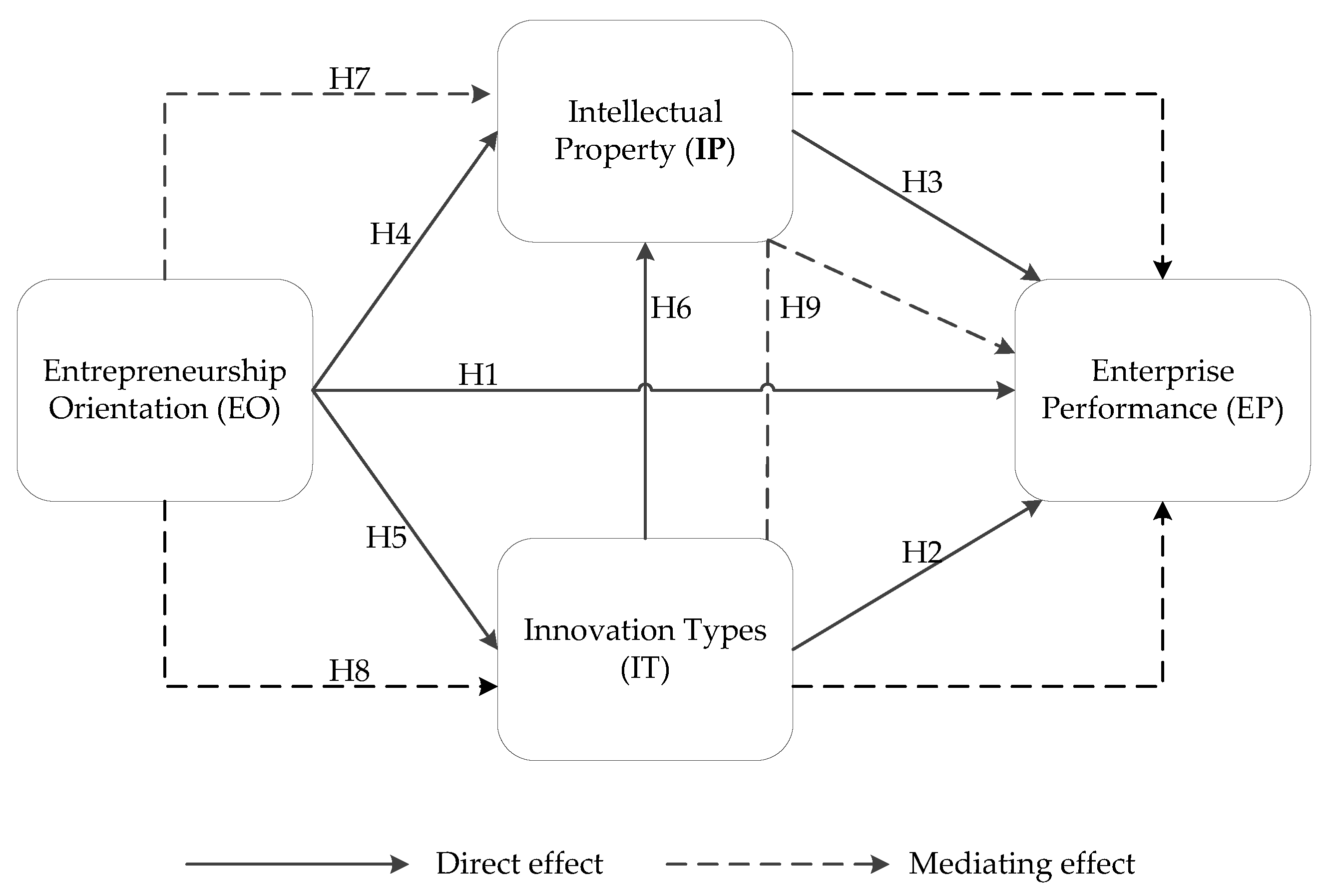

2.2. Hypothesis Development

2.2.1. Entrepreneurial Orientation and Enterprise Performance

2.2.2. Innovation Types and Enterprise Performance

2.2.3. Intellectual Property and Enterprise Performance

2.2.4. Entrepreneurial Orientation and Intellectual Property

2.2.5. Entrepreneurial Orientation and Innovation Types

2.2.6. Innovation Types and Intellectual Property

2.2.7. Mediating Effects of IP in the Relationship between EO and EP

2.2.8. Mediating Effects of IT in the Relationship between EO and EP

2.2.9. Mediating Effects of IP in the Relationship between IT and EP

3. Methods

3.1. Sample Size and Process

3.2. Measures

3.3. Method of Analysis

3.3.1. Tools

3.3.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

4. Results and Discussions

4.1. Demographic Information

4.2. Descriptive Statistics

4.3. Model Fit Calculation

4.4. The Relationship between EO, IT and IP on EP

4.4.1. Relationship between Entrepreneurial Orientation and Enterprise Performance

4.4.2. Relationship between Innovation Types and Enterprise Performance

4.4.3. Relationship between Intellectual Property and Enterprise Performance

4.5. The Mediation Role of Intellectual Property and Innovation Types

4.5.1. The Mediation Role of Innovation Types between Entrepreneurial Orientation and Enterprise Performance

4.5.2. The Mediation Role of Intellectual Property between Entrepreneurial Orientation, Innovation Types, and Enterprise Performance

5. Conclusions

6. Implications

7. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Construct | First Level Indicator | Second Level Indicator | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Entrepreneurial Orientation (OE) | Autonomy (EO_A) | EO_A1 | The manager or owner of this firm upholds strong dominant authority |

| EO_A2 | The manager or owner of this firm has the skill and will to be self-directed in the quest of opportunities | ||

| EO_A3 | Our firm grants little freedom for both individuals and team work | ||

| EO_A4 | We inspire employees to make decision in innovation | ||

| Proactiveness (EO_P) | EO_P1 | We assist in the acknowledgement of clear customer needs | |

| EO_P2 | Our firm is not overwhelmed by new circumstances | ||

| EO_P3 | Our firm acts in expectation of imminent needs | ||

| EO_P4 | We take the lead before competitors follow | ||

| Risk-taking (EO_R) | EO_R1 | Our firm recognizes risk-taking and how it functions | |

| EO_R2 | We see ourselves daring | ||

| EO_R3 | Our firm does not respond to unconnected opportunities | ||

| EO_R4 | Our firm always invests in novel technologies | ||

| Competitive Aggressiveness (EO_C) | EO_C1 | Our firm is ready to be unconventional rather than rely on traditional methods of competing | |

| EO_C2 | We inspire the practice of “undo-the-competitor” attitude | ||

| EO_C3 | We encourage taking advantage of our competitor’s weakness | ||

| EO_C4 | Our firm is prone to the “liability of novelty” | ||

| Innovativeness (EO_INO) | EO_INO1 | Our firm regularly introduces new services/products/processes | |

| EO_INO2 | Our firm has a widely held belief that innovation is an absolute necessity for the firm’s future | ||

| EO_INO3 | Our firm is continually pursuing new opportunities | ||

| EO_INO4 | Our firm places a strong emphasis on new and innovative products/services | ||

| EO_INO5 | Our leaders seek to maximize value from opportunities without constraint to existing models, structures or resources | ||

| Sources: [121,122] | |||

| Innovation Types (IT) | Incremental Innovation (IT_I) | IT_I1 | Our firm regularly enhance current core competencies and capabilities |

| IT_I2 | Our firm responds to customer needs identified from current offers | ||

| IT_I3 | Our firm has a more predictable path or process, particularly with respect to costs | ||

| IT_I4 | Our firm develops modest technological changes from existing platforms, products, or services | ||

| IT_I5 | Our firm is able to improve product/service design | ||

| Radical Innovation (IT_R) | IT_R1 | Our firm works a lot with outsiders, even on a temporary basis | |

| IT_R2 | Our employees have excellent relationship with people who can serve as catalysts for the innovation process | ||

| IT_R3 | Our firm core performance is based on new technology | ||

| IT_R4 | Our firm is able to introduce a whole new set of performance features | ||

| Disruptive Innovation (IT_D) | IT_D1 | Our firm starts with a purpose and a small problem rather than a big idea | |

| IT_D2 | We begin by changing a small group of people at the edges | ||

| IT_D3 | We tap into consumer’s latent desire | ||

| IT_D4 | Our firm is based on what people do, not what they say they do | ||

| IT_D5 | Our firm can be more responsive to customer’s behaviors and needs | ||

| Architectural Innovation (IT_A) | IT_A1 | Our firm invest a lot of resources in research and development (R&D) | |

| IT_A2 | Our firm is able to use the lessons, skills and overall technology and apply them within a different market. | ||

| IT_A3 | Our firm continually update its technology | ||

| IT_A4 | Our firm constantly renew the organizational structure to facilitate teamwork | ||

| Sources: [123,125,126] | |||

| Intellectual Property (IP) | Trade Secrets (IP_TS) | IP_TS1 | We consider trade secrets as strategic value in terms of innovative growth performance and return on investment |

| IP_TS2 | Our firm uses trade secret to protect knowledge that could be protected under other IP rights | ||

| IP_TS3 | We acquire trade secrets from third parties | ||

| IP_TS4 | Our firm apply different protection measures according to the different country where it trades in | ||

| IP_TS5 | We employ payment of wage premia to discourage key employee’s departures as a precaution to protect trade secrets | ||

| Patents (IP_P) | IP_P1 | Acquiring patents improves our firm’s chances of securing investment | |

| IP_P2 | Patent acquisition enhances our firm’s reputation/product image | ||

| IP_P3 | Our firm improve chances of quality liquidity through the patent acquisition | ||

| IP_P4 | Our firm is able to improve negotiating position with other enterprises | ||

| Trademark (IP_TM) | IP_TM1 | Our firm has its own unique trademark | |

| IP_TM2 | Our firm’s trademark is printed on a tag that is affixed to the good | ||

| IP_TM3 | Our firm’s trademark been used extensively in the market | ||

| IP_TM4 | Our trademark is displayed on a website that advertises our goods or services | ||

| IP_TM5 | The goods of our firm are packaged bearing our trademark | ||

| Copyright (IP_CR) | IP_CR1 | Copies of our work have been publicly distributed or given to another for purposes of distribution to the public | |

| IP_CR2 | Our works are normally done anonymously | ||

| IP_CR3 | Our works are prepared by an employee acting within the scope of his/her employment | ||

| IP_CR4 | In our firm applicant owns copyright, as author signed written agreement assigning rights to work | ||

| IP_CR5 | Our works are never derived, or based on, a pre-existing work | ||

| Source: [127] | |||

| Enterprise Performance (EP) | Increase in Number of Employees (EP_INE) | EP_INE1 | Our firm has experienced an increase in the number of employees within the past few years |

| EP_INE2 | In our business, employees are viewed as the most valuable asset of the business | ||

| EP_INE3 | Our employees are highly committed to our business | ||

| EP_INE4 | Our firm has room for more full-time employees in the coming months | ||

| EP_INE5 | We have had to lay-off employees within the past few years | ||

| Increase in Sales (EP_IS) | EP_IS1 | Our firm has experienced a stable increase in sales within the past few years | |

| EP_IS2 | Our firm has achieved its sales objective within the past few years | ||

| EP_IS3 | Our firm has experienced growth in turnover over the past few years | ||

| EP_IS4 | Over the last few years, comparative to major competitors, our firm’s overall sales revenue has been increasing | ||

| EP_IS5 | Our firm’s average return on sales are always high | ||

| Increase in Profits (EP_IP) | EP_IP1 | Our firm has experienced growth in profit over the past few years | |

| EP_IP2 | Over the last few years, comparative to major competitors, our firm’s overall return on investment has been much lower | ||

| EP_IP3 | Over the last few years, relative to major competitors, our firm’s overall return on assets has been much higher | ||

| EP_IP4 | Despite the external business factors on our business our firm has been able to make profit daily | ||

| Increase in Market Share (EP_IMS) | EP_IMS1 | Our firm has experienced growth in market share over the past few years | |

| EP_IMS2 | Over the last few years, comparative to major competitors, our firm’s overall return on assets has been much higher | ||

| EP_IMS3 | Our firm has a lot of customers as compared to our competitors | ||

| EP_IMS4 | Our firm’s pricing system is the best as compared to our competitors | ||

| Sources: [121,122,128,129] | |||

| Constructs | First Level Construct | Items | Loadings | Eigen Value | CR | Percentage Variance | Cronbach’s Alpha | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entrepreneurial Orientation (EO) | EO_INO | EO_INO1 | 0.731 | 6.849 | 0.861 | 15.720 | 0.858 | 0.554 |

| EO_INO2 | 0.744 | |||||||

| EO_INO3 | 0.738 | |||||||

| EO_INO4 | 0.718 | |||||||

| EO_INO5 | 0.787 | |||||||

| EO_A | EO_A1 | 0.686 | 2.025 | 0.837 | 13.405 | 0.817 | 0.564 | |

| EO_A 2 | 0.835 | |||||||

| EO_A 3 | 0.781 | |||||||

| EO_A 4 | 0.692 | |||||||

| EO_R | EO_R1 | 0.777 | 1.851 | 0.808 | 13.379 | 0.767 | 0.514 | |

| EO_R2 | 0.738 | |||||||

| EO_R3 | 0.646 | |||||||

| EO_R4 | 0.701 | |||||||

| EO_C | EO_C1 | 0.674 | 1.420 | 0.828 | 11.404 | 0.703 | 0.548 | |

| EO_C2 | 0.767 | |||||||

| EO_C3 | 0.815 | |||||||

| EO_C4 | 0.697 | |||||||

| EO_P | EO_P1 | 0.672 | 1.202 | 0.776 | 9.648 | 0.712 | 0.501 | |

| EO_P2 | 0.723 | |||||||

| EO_P3 | 0.674 | |||||||

| EO_P4 | 0.656 |

| Constructs | First Level Construct | Items | Loadings | Eigen Value | CR | Percentage Variance | Cronbach’s Alpha | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Innovation Types (IT) | IT_I | IT_I1 | 0.836 | 7.292 | 0.856 | 17.418 | 0.839 | 0.545 |

| IT_I2 | 0.727 | |||||||

| IT_I3 | 0.785 | |||||||

| IT_I4 | 0.707 | |||||||

| IT_I5 | 0.618 | |||||||

| IT_D | IT_D1 | 0.812 | 1.454 | 0.829 | 15.251 | 0.843 | 0.501 | |

| IT_D2 | 0.715 | |||||||

| IT_D3 | 0.729 | |||||||

| IT_D4 | 0.639 | |||||||

| IT_D5 | 0.602 | |||||||

| IT_A | IT_A1 | 0.688 | 1.097 | 0.800 | 13.694 | 0.749 | 0.502 | |

| IT_A2 | 0.685 | |||||||

| IT_A3 | 0.777 | |||||||

| IT_A4 | 0.678 | |||||||

| IT_R | IT_R1 | 0.766 | 0.936 | 0.799 | 13.520 | 0.757 | 0.500 | |

| IT_R2 | 0.759 | |||||||

| IT_R3 | 0.672 | |||||||

| IT_R4 | 0.622 |

| Constructs | First Level Construct | Items | Loadings | Eigen Value | CR | Percentage Variance | Cronbach’s Alpha | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intellectual Property (IP) | IP_TS | IP_TS1 | 0.643 | 7.309 | 0.856 | 18.674 | 0.842 | 0.544 |

| IP_TS2 | 0.722 | |||||||

| IP_TS3 | 0.799 | |||||||

| IP_TS4 | 0.716 | |||||||

| IP_TS5 | 0.797 | |||||||

| IP_CR | IP_CR1 | 0.767 | 3.224 | 0.915 | 18.505 | 0.835 | 0.683 | |

| IP_CR2 | 0.838 | |||||||

| IP_CR3 | 0.858 | |||||||

| IP_CR4 | 0.832 | |||||||

| IP_CR5 | 0.836 | |||||||

| IP_TM | IP_TM1 | 0.607 | 1.245 | 0.815 | 16.218 | 0.842 | 0.500 | |

| IP_TM2 | 0.639 | |||||||

| IP_TM3 | 0.773 | |||||||

| IP_TM4 | 0.781 | |||||||

| IP_TM5 | 0.613 | |||||||

| IP_P | IP_P1 | 0.725 | 0.885 | 0.863 | 13.252 | 0.764 | 0.612 | |

| IP_P2 | 0.762 | |||||||

| IP_P3 | 0.814 | |||||||

| IP_P4 | 0.823 |

| Constructs | First Level Construct | Items | Loadings | Eigen Value | CR | Percentage Variance | Cronbach’s Alpha | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enterprise Performance (EP) | EP_INE | EP_INE1 | 0.863 | 6.367 | 0.921 | 19.915 | 0.866 | 0.701 |

| EP_INE2 | 0.862 | |||||||

| EP_INE3 | 0.809 | |||||||

| EP_INE4 | 0.830 | |||||||

| EP_INE5 | 0.820 | |||||||

| EP_IS | EP_IS1 | 0.694 | 3.244 | 0.844 | 17.774 | 0.845 | 0.522 | |

| EP_IS2 | 0.673 | |||||||

| EP_IS3 | 0.767 | |||||||

| EP_IS4 | 0.790 | |||||||

| EP_IS5 | 0.681 | |||||||

| EP_IMS | EP_IMS1 | 0.731 | 1.224 | 0.788 | 14.491 | 0.752 | 0.500 | |

| EP_IMS2 | 0.721 | |||||||

| EP_IMS3 | 0.719 | |||||||

| EP_IMS4 | 0.603 | |||||||

| EP_IP | EP_IP1 | 0.672 | 1.061 | 0.839 | 13.912 | 0.767 | 0.567 | |

| EP_IP2 | 0.772 | |||||||

| EP_IP3 | 0.770 | |||||||

| EP_IP4 | 0.791 |

References

- WHO. Available online: http://www.who.int (accessed on 8 December 2020).

- Chen, H.; Guo, J.; Wang, C.; Luo, F.; Yu, X.; Zhang, W.; Li, J.; Zhao, D.; Xu, D.; Gong, Q. Clinical characteristics and intrauterine vertical transmission potential of COVID-19 infection in nine pregnant women: A retrospective review of medical records. Lancet 2020, 395, 809–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donthu, N.; Gustafsson, A. Effects of COVID-19 on business and research. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 117, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abor, J.; Quartey, P. Issues in SME development in Ghana and South Africa. Int. Res. J. Financ. Econ. 2010, 39, 215–228. [Google Scholar]

- Obi, J.; Ibidunni, A.S.; Tolulope, A.; Olokundun, M.A.; Amaihian, A.B.; Borishade, T.T.; Fred, P. Contribution of small and medium enterprises to economic development: Evidence from a transiting economy. Data Brief. 2018, 18, 835–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- OECD. Report of the Chair of the Working Group on the Future Size and Membership of the Organisation to Council; OECD: Paris, France, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Tehseen, S.; Ahmed, F.U.; Qureshi, Z.H.; Uddin, M.J.; Ramayah, T. Entrepreneurial competencies and SMEs’ growth: The mediating role of network competence. Asia-Pac. J. Bus. Adm. 2019, 11, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agbola, R.M.; Amoah, A. Coding Systems and Effective Inventory Management of SMEs in the Ghanaian Retail Industry. Cent. Inq. 2019, 1, 46–65. [Google Scholar]

- Stephen, E. SMEs contribute 70% to Ghana’s GDP. Today Newspaper, 17 November 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Affum, E.K.; Wang, H. The Food Industry in Ghana: Demystifying the Innovation and Quality Conundrum. Food Ind. 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Institute of Statistical, Social and Economic Research (ISSER). Social and Economic Research. In The State of the Ghanaian Economy in 2016; University of Ghana: Legon Boundary, Accra, Ghana, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Manufacturing: Struggling to survive. In UNESCO Ghana Report; Ghana Education Service: Accra, Ghana, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Sutton, J.; Kpentey, B. An Enterprise Map of Ghana; International Growth Centre in Association with the London Publishing Partnership: London, UK, 2012; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- GNCCI Business Survey. COVID-19 Examining the Concerns and Expectations of Businesses in Ghana Finalised; Ghana National Chamber of Commerce and Industry: Tarkwa, Ghana, 2020; pp. 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Yawised, K.; O’Donohue, W. Social Customer Relationship Management in Small and Medium Enterprises: Overcoming Barriers to Success. In Management Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 157–181. [Google Scholar]

- Petković, S.; Jäger, C.; Sašić, B. Challenges of small and medium sized companies at early stage of development: Insights from Bosnia and Herzegovina. Manag. J. Contemp. Manag. Issues 2016, 21, 45–76. [Google Scholar]

- Poudel, K.P.; Carter, R.; Lonial, S. The Impact of Entrepreneurial Orientation, Technological Capability, and Consumer Attitude on Firm Performance: A Multi-Theory Perspective. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2019, 2, 268–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amponsah, R.; Frimpong, I.A. Ghana in the Face of COVID-19: Economic Impact of Coronavirus (2019-NCOV) Outbreak on Ghana. Open J. Bus. Manag. 2020, 8, 1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quaye, D.; Mensah, I. Marketing innovation and sustainable competitive advantage of manufacturing SMEs in Ghana. Manag. Decis. 2019, 57, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quartey, P.; Turkson, E.; Abor, J.Y.; Iddrisu, A.M. Financing the growth of SMEs in Africa: What are the contraints to SME financing within ECOWAS? Rev. Dev. Financ. 2017, 7, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeebaree, M.R.Y.; Siron, R.B. The impact of entrepreneurial orientation on competitive advantage moderated by financing support in SMEs. Int. Rev. Manag. Mark. 2017, 7, 43–52. [Google Scholar]

- Sirivanh, T.; Sukkabot, S.; Sateeraroj, M. The effect of entrepreneurial orientation and competitive advantage on SMEs’ growth: A structural equation modeling study. Int. J. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2014, 5, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Sabahi, S.; Parast, M.M. The impact of entrepreneurship orientation on project performance: A machine learning approach. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2020, 226, 107621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devece, C.; Peris-Ortiz, M.; Rueda-Armengot, C. Entrepreneurship during economic crisis: Success factors and paths to failure. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 5366–5370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desbureaux, S.; Kaota, A.; Lunanga, E.; Stoop, N.; Verpoorten, M. Covid-19 vs. Ebola: Impact on households and SMEs in Nord Kivu, DR Congo; IOB Working Paper: Antwerp, Belgium, 2020; pp. 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Kottika, E.; Özsomer, A.; Rydén, P.; Theodorakis, I.G.; Kaminakis, K.; Kottikas, K.G.; Stathakopoulos, V. We survived this! What managers could learn from SMEs who successfully navigated the Greek economic crisis. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2020, 88, 352–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, S.; Rigtering, J.C.; Hughes, M.; Hosman, V. Entrepreneurial orientation and the business performance of SMEs: A quantitative study from the Netherlands. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2012, 6, 161–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asad, M.; Shabbir, M.; Salman, R.; Haider, S.; Ahmad, I. Do entrepreneurial orientation and size of enterprise influence the performance of micro and small enterprises? A study on mediating role of innovation. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2018, 8, 1015–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kee, D.M.H.; Rahman, N.A. Analyzing entrepreneurial orientation impact on start-up success with support service as moderator: A PLS-SEM approach. Bus. Econ. Horiz. (BEH) 2017, 13, 128–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Gelderen, M.; Kibler, E.; Kautonen, T.; Munoz, P.; Wincent, J. Mindfulness and taking action to start a new business. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2019, 57, 489–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, A.M.; Casillas, J.C. Entrepreneurial orientation and growth of SMEs: A causal model. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2008, 32, 507–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, J.; Ortt, R. Entrepreneurial orientation and firm performance: The mediating role of functional performances. Manag. Res. Rev. 2018, 41, 878–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juergensen, J.; Guimón, J.; Narula, R. European SMEs amidst the COVID-19 crisis: Assessing impact and policy responses. J. Ind. Bus. Econ. 2020, 47, 499–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuscheler, D.; Engelen, A.; Zahra, S.A. The role of top management teams in transforming technology-based new ventures’ product introductions into growth. J. Bus. Ventur. 2019, 34, 122–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covin, J.G.; Lumpkin, G.T. Entrepreneurial orientation theory and research: Reflections on a needed construct. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2011, 35, 855–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumpkin, G.T.; Dess, G.G. Clarifying the entrepreneurial orientation construct and linking it to performance. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1996, 21, 135–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampe, J.; Kraft, P.S.; Bausch, A. Mapping the Field of Research on Entrepreneurial Organizations (1937–2016): A Bibliometric Analysis and Research Agenda. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2019, 44, 784–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuratko, D.F.; Morris, M.H. Examining the future trajectory of entrepreneurship. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2018, 56, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mintzberg, H. Strategy-making in three modes. Calif. Manag. Rev. 1973, 16, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covin, J.G.; Slevin, D.P. Strategic management of small firms in hostile and benign environments. Strateg. Manag. J. 1989, 10, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D. The correlates of entrepreneurship in three types of firms. Manag. Sci. 1983, 29, 770–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covin, J.G.; Slevin, D.P. A conceptual model of entrepreneurship as firm behavior. Entrep. Theory Pract. 1991, 16, 7–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuratko, D.F. Entrepreneurial leadership in the 21st century: Guest editor’s perspective. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2007, 13, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X.E. The effect of entrepreneurial orientation on business performance: A role of network capabilities in China. J. Chin. Entrep. 2012, 4, 132–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, K.; Hasnain, S.S.U.; Awais, M.; Shahzadi, I.; Afzal, M.M. The Impact of Entrepreneurial Orientation on SME Performance in Pakistan: A Qualitative Analysis. Int. J. Eng. Inf. Syst. (IJEAIS) 2017, 1, 107–112. [Google Scholar]

- Pratono, A.H.; Mahmood, R. Entrepreneurial orientation and firm performance: How can micro, small and medium-sized enterprises survive environmental turbulence? Pac. Sci. Rev. B Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2015, 1, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taheri, B.; Bititci, U.; Gannon, M.J.; Cordina, R. Investigating the influence of performance measurement on learning, entrepreneurial orientation and performance in turbulent markets. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 31, 1224–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simba, A.; Thai, M.T.T. Advancing Entrepreneurial Leadership as a Practice in MSME Management and Development. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2019, 57, 397–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, S.; Yadav, S. Entrepreneurial orientation of SMEs, total quality management and firm performance. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2017, 28, 892–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauch, A.; Wiklund, J.; Lumpkin, G.; Frese, M. Entrepreneurial Orientation and Business Performance: Cumulative Empirical Evidence; University of Exeter: Exeter, England, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrontis, D.; Thrassou, A.; Chebbi, H.; Yahiaoui, D. Transcending innovativeness towards strategic reflexivity. Qual. Mark. Res. Int. J. 2012, 15, 420–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdilahi, M.H.; Hassan, A.A.; Muhumed, M.M. The Impact of Innovation on Small and Medium Enterprises Performance: Empirical Evidence from Hargeisa, Somaliland. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2017, 7, 14–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olughor, R.J. Effect of innovation on the performance of SMEs organizations in Nigeria. Management 2015, 5, 90–95. [Google Scholar]

- Rosli, M.M.; Sidek, S. The Impact of Innovation on the Performance of Small and Medium Manufacturing Enterprises: Evidence from Malaysia. J. Innov. Manag. Small Medium Enterp. 2013, 2013, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welsch, H.; Price, D.P.; Stoica, M. Innovation, Performance and Growth Intentions in SMEs. Int. J. Econ. Manag. Eng. 2013, 3, 176. [Google Scholar]

- Zwingina, C.; Opusunju, M. Impact of innovation on the performance of small and medium scale enterprise in Gwagwalada, Abuja. Int. J. Entrep. Dev. Educ. Sci. Res. 2017, 4, 31–43. [Google Scholar]

- Li, B.; Huang, L. The Effect of Incremental Innovation and Disruptive Innovation on the Sustainable Development of Manufacturing in China. Sage Open 2019, 9, 2158244019832700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zentner, A. Disruptive Innovation: A Catalyst for Change in Business and Market Modeling. 2015. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2522812 (accessed on 8 December 2020).

- Shih, T.-Y. Determinants of enterprises radical innovation and performance: Insights into strategic orientation of cultural and creative enterprises. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Atuahene-Gima, K. Product innovation strategy and the performance of new technology ventures in China. Acad. Manag. J. 2001, 44, 1123–1134. [Google Scholar]

- Rajapathirana, R.J.; Hui, Y. Relationship between innovation capability, innovation type, and firm performance. J. Innov. Knowl. 2018, 3, 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E.; Kramer, M.R. Creating shared value. In Managing Sustainable Business; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 323–346. [Google Scholar]

- Kretschmer, M.; Soetendorp, R. The strategic use of business method patents: A pilot study of out of court settlements. J. E-Bus. 2001, 2, 9–38. [Google Scholar]

- Chirico, F.; Criaco, G.; Baù, M.; Naldi, L.; Gomez-Mejia, L.R.; Kotlar, J. To patent or not to patent: That is the question. Intellectual property protection in family firms. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2018, 44, 339–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artz, K.W.; Norman, P.M.; Hatfield, D.E.; Cardinal, L.B. A longitudinal study of the impact of R&D, patents, and product innovation on firm performance. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2010, 27, 725–740. [Google Scholar]

- Holgersson, M.; Granstrand, O. Patenting motives, technology strategies, and open innovation. Manag. Decis. 2017, 55, 1265–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, K.-C.; Chen, D.-Z.; Huang, M.-H. The relationships between the patent performance and corporation performance. J. Informetr. 2012, 6, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernst, H. Patent applications and subsequent changes of performance: Evidence from time-series cross-section analyses on the firm level. Res. Policy 2001, 30, 143–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo-Fitoussi, L.; Bounfour, A.; Rekik, S. Intellectual property rights, complementarity and the firm’s economic performance. Int. J. Intellect. Prop. Manag. 2019, 9, 136–165. [Google Scholar]

- Rank, O.N.; Strenge, M. Entrepreneurial orientation as a driver of brokerage in external networks: Exploring the effects of risk taking, proactivity, and innovativeness. Strateg. Entrep. J. 2018, 12, 482–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, S.; McLean, G.N.; Park, S. Understanding informal learning in small-and medium-sized enterprises in South Korea. J. Workplace Learn. 2018, 30, 89–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athreye, S.; Fassio, C. Why do innovators not apply for trademarks? The role of information asymmetries and collaborative innovation. Ind. Innov. 2020, 27, 134–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shane, S.; Venkataraman, S. The promise of entrepreneurship as a field of research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2000, 25, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, S.; Burtscher, J.; Vallaster, C.; Angerer, M. Sustainable entrepreneurship orientation: A reflection on status-quo research on factors facilitating responsible managerial practices. Sustainability 2018, 10, 444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, N.; Yordanova, Z. Why say no to innovation? Evidence from industrial SMEs in European Union. J. Technol. Manag. Innov. 2018, 13, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Minafam, Z. Corporate Entrepreneurship and Innovation Performance in Established Iranian Media Firms. Ad-Minister 2019, 34, 77–100. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, B.S.; Covin, J.G.; Slevin, D.P. Understanding the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and strategic learning capability: An empirical investigation. Strateg. Entrep. J. 2009, 3, 218–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Dass, M.; Arnett, D.B.; Yu, X. Understanding firms’ relative strategic emphases: An entrepreneurial orientation explanation. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2019, 84, 151–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wales, W.J. Entrepreneurial orientation: A review and synthesis of promising research directions. Int. Small Bus. J. 2016, 34, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafeez, M.H.; Shariff, M.N.M.; Lazim, H.B.M. Relationship between entrepreneurial orientation, firm resources, SME branding and firm’s performance: Is innovation the missing link. Am. J. Ind. Bus. Manag. 2012, 2, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Harms, R.; Schulz, A.; Kraus, S.; Fink, M. The conceptualisation of’opportunity’in strategic management research. Int. J. Entrep. Ventur. 2009, 1, 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arzubiaga, U.; Kotlar, J.; De Massis, A.; Maseda, A.; Iturralde, T. Entrepreneurial orientation and innovation in family SMEs: Unveiling the (actual) impact of the Board of Directors. J. Bus. Ventur. 2018, 33, 455–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar, N.A.; Aris, H.M.; Nazri, M.A. The effect of entrepreneurial orientation, innovation capability and knowledge creation on firm performance: A perspective on small scale entrepreneurs. J. Pengur. (J. Manag.) 2016, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naidu, A.A. Examining the Relationship between Entrepreneurial Orientation, the Strategic Decision-Making Process and Organisational Performance: A Study of Singapore SMEs. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Western Australia, Crawley, WA, Australia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Madhoushi, M.; Sadati, A.; Delavari, H.; Mehdivand, M.; Mihandost, R. Entrepreneurial orientation and innovation performance: The mediating role of knowledge management. Asian J. Bus. Manag. 2011, 3, 310–316. [Google Scholar]

- Nasir, W.M. The Relationship between Strategic Orientation and Firm Performance: Evidence from Small and Medium Enterprises in Malaysia; Victoria University: Footscray, VIC, Australia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bodlaj, M.; Čater, B. The Impact of Environmental Turbulence on the Perceived Importance of Innovation and Innovativeness in SMEs. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2019, 2, 417–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, Y.-M.; Sun, W.-Q.; Tsai, S.-B.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, Q. An Empirical Study on Entrepreneurial Orientation, Absorptive Capacity, and SMEs’ Innovation Performance: A Sustainable Perspective. Sustainability 2018, 10, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tidd, J.; Bessant, J.R. Managing Innovation: Integrating Technological, Market and Organizational Change; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Fink, C.; Raffo, J. What Role for Intellectual Property in Industrial Development? In Intellectual Property and Development: Understanding the Interfaces; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 119–136. [Google Scholar]

- Chandra, G.R.; Liaqat, I.A. Commercialization of Intellectual Property; an Insight for Technocrats. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Automation, Computational and Technology Management (ICACTM), London, UK, 24–26 April 2019; pp. 373–378. [Google Scholar]

- Morikawa, M. Innovation in the service sector and the role of patents and trade secrets: Evidence from Japanese firms. J. Jpn. Int. Econ. 2019, 51, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalanje, C.M. Role of Intellectual Property in Innovation and New Product Development; World Intellectual Property Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Naveiro, R. Role of Intellectual Property in Innovation and New Product Development. Master’s Thesis, Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Iksanova, L.; Kashapov, N. Intellectual property as a factor of increasing innovation activity of economic entities. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 412, 012028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherwood, R.M. Intellectual Property and Economic Development; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Rushing, F.W. Intellectual Property Rights in Science, Technology, and Economic Performance: International Comparisons; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Dzenopoljac, V.; Yaacoub, C.; Elkanj, N.; Bontis, N. Impact of intellectual capital on corporate performance: Evidence from the Arab region. J. Intellect. Cap. 2017, 18, 884–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamm, J.B.; Shuman, J.C.; Seeger, J.A.; Nurick, A.J. Entrepreneurial teams in new venture creation: A research agenda. Entrep. Theory Pract. 1990, 14, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, P.; Song, M.; Ju, X. Entrepreneurial orientation and performance: Is innovation speed a missing link? J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 683–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuart, R.; Abetti, P.A. Start-up ventures: Towards the prediction of initial success. J. Bus. Ventur. 1987, 2, 215–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheah, J.; Amran, A.; Yahya, S. External oriented resources and social enterprises’ performance: The dominant mediating role of formal business planning. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 236, 117693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calisir, F.; Altin, G.C.; Guzelsoy, E. Impacts of learning orientation on product innovation performance. Learn. Organ. 2013, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avlonitis, G.J.; Salavou, H.E. Entrepreneurial orientation of SMEs, product innovativeness, and performance. J. Bus. Res. 2007, 60, 566–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hami, N.; Muhamad, M.R.; Ebrahim, Z. The impact of sustainable manufacturing practices and innovation performance on economic sustainability. Procedia Cirp 2015, 26, 190–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajasom, A.; Hung, D.K.M.; Nikbin, D.; Hyun, S.S. The role of transformational leadership in innovation performance of Malaysian SMEs. Asian J. Technol. Innov. 2015, 23, 172–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Hallak, R.; Sardeshmukh, S.R. Innovation, entrepreneurship, and restaurant performance: A higher-order structural model. Tour. Manag. 2016, 53, 215–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davila, T.; Epstein, M.; Shelton, R. Making Innovation Work: How to Manage It, Measure It, and Profit from It; FT Press: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Joe, T.; Fiona, S. Innovation Heroes: Understanding Customers as a Valuable Innovation Resource; World Scientific: Singapore, 2018; Volume 31. [Google Scholar]

- Kronthaler, M.M. Innovation Heroes–Understanding Customers as a Valuable Innovation Resource; Fiona, S., Joe, T., Eds.; World Scientific Publishing Europe: London, UK, 2018; ISBN 978-1786345363. [Google Scholar]

- de Zubielqui, G.C.; Lindsay, N.; Lindsay, W.; Jones, J. Knowledge quality, innovation and firm performance: A study of knowledge transfer in SMEs. Small Bus. Econ. 2019, 53, 145–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Zou, F.; Zhang, P. The role of innovation for performance improvement through corporate social responsibility practices among small and medium-sized suppliers in C hina. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 26, 341–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadani, V.; Hisrich, R.D.; Abazi-Alili, H.; Dana, L.-P.; Panthi, L.; Abazi-Bexheti, L. Product innovation and firm performance in transition economies: A multi-stage estimation approach. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2019, 140, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabić, M.; Lažnjak, J.; Smallbone, D.; Švarc, J. Intellectual capital, organisational climate, innovation culture, and SME performance: Evidence from Croatia. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2019, 26, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalique, M.; Bontis, N.; Shaari, J.A.N.B.; Yaacob, M.R.; Ngah, R. Intellectual capital and organisational performance in Malaysian knowledge-intensive SMEs. Int. J. Learn. Intellect. Cap. 2018, 15, 20–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, P.; Lu, H.; Hong, J.; Chen, Q.; Yang, Y. Government R&D subsidies, intellectual property rights protection and innovation. Chin. Manag. Stud. 2019, 13, 363–378. [Google Scholar]

- Davoudi, S.M.M.; Fartash, K.; Venera, G.Z.; Asiya, M.B.; Rashad, A.K.; Anna, V.B.; Zhanna, M.S. Testing the Mediating Role of Open Innovation on the Relationship between Intellectual Property Rights and Organizational Performance: A Case of Science and Technology Park. Eurasia J. Math. Sci. Technol. Educ. 2018, 14, 1359–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibarra Cisneros, M.A.; Hernandez-Perlines, F. Intellectual capital and Organization performance in the manufacturing sector of Mexico. Manag. Decis. 2018, 56, 1818–1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aminu, M.I.; Mahmood, R. Mediating role of dynamic capabilities on the relationship between intellectual capital and performance: A hierarchical component model perspective in PLS-SEM path modeling. Res. J. Bus. Manag. 2015, 9, 443–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alembummah, A.B. Entrepreneurial Orientation and SME Growth: A Study of the Food Processing Sector of Ghana; MPhil, University of Ghana: Legon Boundary, Accra, Ghana, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Venter, A. An Analysis of the Influence of Entrepreneurial Orientation on Business Success in Selected Small and Medium–Sized Enterprises; North-West University: Evanston, IL, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Damanpour, F. Organizational innovation: A meta-analysis of effects of determinants and moderators. Acad. Manag. J. 1991, 34, 555–590. [Google Scholar]

- Moch, M.; Pondy, L. The structure of chaos: Organized anarchy as a response to ambiguity. JSTOR 1977, 22, 351–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewar, R.D.; Dutton, J.E. The adoption of radical and incremental innovations: An empirical analysis. Manag. Sci. 1986, 32, 1422–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, P.D.; Hage, J.; Hull, F.M. Organizational and technological predictors of change in automaticity. Acad. Manag. J. 1988, 31, 512–543. [Google Scholar]

- Linton, G. The Future, Entrepreneurship, and Innovation: A Note on the Importance of the Getting Entrepreneurship and Innovation Right for a Sustainable Future; Örebro University School of Business: Örebro, Sweden, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, D. Measuring Performance in Small and Medium Enterprises in the Information and Communication Technology Industries. Ph.D. Thesis, RMIT University, Melbourne, VIC, Australia, February 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Akrofi, A.E. The Impact of External Business Environment Factors on Performance of Small & Medium Sized Enterprises in the Pharmaceutical Industry in Kumasi Metropolis; Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology: Kumasi, Ghana, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kuppelwieser, V.G.; Putinas, A.-C.; Bastounis, M. Toward application and testing of measurement scales and an example. Sociol. Methods Res. 2019, 48, 326–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Sadick, M.A.; Musah, A.-A.I.; Mustapha, S. The Moderating Effect of Social Innovation in Perspectives of Shared Value Creation in the Educational Sector of Ghana. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringle, C.M.; Wende, S.; Becker, J.-M. SmartPLS 3. SmartPLS GmbH, Boenningstedt. J. Serv. Sci. Manag. 2015, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2011, 19, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Smith, D.; Reams, R.; Hair, J.F., Jr. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM): A useful tool for family business researchers. J. Fam. Bus. Strategy 2014, 5, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, H.; Zhiqiang, M.; Abubakari Sadick, M.; Ibn Musah, A.-A. Investigating the Role of Psychological Contract Breach, Political Skill and Work Ethic on Perceived Politics and Job Attitudes Relationships: A Case of Higher Education in Pakistan. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cegarra-Navarro, J.-G.; Reverte, C.; Gómez-Melero, E.; Wensley, A.K. Linking social and economic responsibilities with financial performance: The role of innovation. Eur. Manag. J. 2016, 34, 530–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeung, P. SPSS survival manual. A step by step guide to data analysis using IBM SPSS [Book Review]. Aotearoa N. Z. Soc. Work 2014, 26, 92. [Google Scholar]

- McNeish, D.; An, J.; Hancock, G.R. The thorny relation between measurement quality and fit index cutoffs in latent variable models. J. Personal. Assess. 2018, 100, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ta, A.; Prybutok, V. A mindful product acceptance model. J. Decis. Syst. 2018, 27, 19–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Gudergan, S.P. Advanced Issues in Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling; Sage Publications: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.-t.; Bentler, P.M. Fit indices in covariance structure modeling: Sensitivity to underparameterized model misspecification. Psychol. Methods 1998, 3, 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Jinini, D.K.; Dahiyat, S.E.; Bontis, N. Intellectual capital, entrepreneurial orientation, and technical innovation in small and medium-sized enterprises. Knowl. Process. Manag. 2019, 26, 69–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danneels, E.; Vestal, A. Normalizing vs. analyzing: Drawing the lessons from failure to enhance firm innovativeness. J. Bus. Ventur. 2020, 35, 105903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelderen, M.V. Entrepreneurial autonomy and its dynamics. Appl. Psychol. 2016, 65, 541–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiVito, L.; Bohnsack, R. Entrepreneurial orientation and its effect on sustainability decision tradeoffs: The case of sustainable fashion firms. J. Bus. Ventur. 2017, 32, 569–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallmuenzer, A.; Strobl, A.; Peters, M. Tweaking the entrepreneurial orientation–performance relationship in family firms: The effect of control mechanisms and family-related goals. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2018, 12, 855–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, C.M.; McDonald, R.; Altman, E.J.; Palmer, J.E. Disruptive innovation: An intellectual history and directions for future research. J. Manag. Stud. 2018, 55, 1043–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulze-Krogh, A.C.; Calignano, G. How Do Firms Perceive Interactions with Researchers in Small Innovation Projects? Advantages and Barriers for Satisfactory Collaborations. J. Knowl. Econ. 2019, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grashof, N.; Hesse, K.; Fornahl, D. Radical or not? The role of clusters in the emergence of radical innovations. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2019, 27, 1904–1923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, D.S.; Sichelman, T. Why Do Startups Use Trade Secrets. Notre Dame L. Rev. 2018, 94, 751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lie, H.T. Trade Secrets and Lead Time Advantages-Understanding Innovation Appropriation Mechanisms. SSRN Electron. J. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta, M.; Coronado, D.; Ferrandiz, E.; Marin, M.R.; Moreno, P.J. Patents and Dual-use Technology: An Empirical Study of the World’s Largest Defence Companies. Def. Peace Econ. 2018, 29, 821–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); Sage publications: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X.; Lynch, J.G., Jr.; Chen, Q. Reconsidering Baron and Kenny: Myths and truths about mediation analysis. J. Consum. Res. 2010, 37, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varadarajan, R. Fortune at the bottom of the innovation pyramid: The strategic logic of incremental innovations. Bus. Horiz. 2009, 52, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amewu, S.; Asante, S.; Pauw, K.; Thurlow, J. The economic costs of COVID-19 in sub-Saharan Africa: Insights from a simulation exercise for Ghana. Eur. J. Dev. Res. 2020, 32, 1353–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danquah, M.; Schotte, S.; Sen, K. COVID-19 and Employment: Insights from the Sub-Saharan African Experience. Indian J. Labour Econ. 2020, 63, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamfo, B.A.; Kraa, J.J. Market orientation and performance of small and medium enterprises in Ghana: The mediating role of innovation. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2019, 6, 1605703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Model | SRMR | d_ULS | d_G | Chi-Square | NFI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Saturated Model | 0.083 | 1.727 | 0.714 | 2622.54 | 0.931 |

| Constructs | AVE | EO | EP | IP | IT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EO | 0.536 | 0.710 | |||

| EP | 0.573 | 0.639 | 0.764 | ||

| IP | 0.585 | 0.646 | 0.725 | 0.811 | |

| IT | 0.512 | 0.716 | 0.793 | 0.712 | 0.831 |

| Constructs | EO | EP | IP | IT |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EO | ||||

| EP | 0.639 | |||

| IP | 0.646 | 0.725 | ||

| IT | 0.716 | 0.793 | 0.712 |

| Path Relations | Beta | Standard Error | t-Value | p-Values | 95% CI | R Square | Q Square | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.5% | 97.5% | |||||||

| EO -> EP | 0.116 | 0.040 | 2.949 | 0.003 | 0.047 | 0.196 | 0.458 | 0.251 |

| IT -> EP | 0.126 | 0.053 | 2.361 | 0.019 | 0.026 | 0.233 | 0.577 | 0.318 |

| IP -> EP | 0.670 | 0.058 | 11.517 | 0.000 | 0.555 | 0.779 | 0.754 | 0.415 |

| EO -> IP | 0.145 | 0.045 | 3.222 | 0.008 | 0.124 | 0.167 | 0.523 | 0.311 |

| EO -> IT | 0.716 | 0.041 | 17.464 | 0.000 | 0.622 | 0.786 | 0.602 | 0.466 |

| IT -> IP | 0.840 | 0.029 | 27.866 | 0.000 | 0.777 | 0.893 | 0.803 | 0.567 |

| Hypothesis | Path Relations | Beta | Standard Error | t-Value | p-Values | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | EO -> EP | 0.116 | 0.040 | 2.949 | 0.003 *** | Supported |

| H2 | IT -> EP | 0.126 | 0.053 | 2.361 | 0.019 *** | Supported |

| H3 | IP -> EP | 0.670 | 0.058 | 11.517 | 0.000 *** | Supported |

| H4 | EO -> IP | 0.145 | 0.045 | 3.222 | 0.008 *** | Supported |

| H5 | EO -> IT | 0.716 | 0.041 | 17.464 | 0.000 *** | Supported |

| H6 | IT -> IP | 0.840 | 0.029 | 27.866 | 0.000 *** | Supported |

| Path Relations | Beta | Standard Error | t-Value | p-Values | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.5% | 97.5% | |||||

| EO -> IP -> EP | 0.430 | 0.030 | 14.333 | 0.001 | 0.331 | 0.587 |

| EO -> IT -> EP | 0.090 | 0.039 | 2.292 | 0.024 | 0.013 | 0.163 |

| IT -> IP -> EP | 0.563 | 0.058 | 9.663 | 0.000 | 0.421 | 0.684 |

| Model | SRMR | d_ULS | d_G | Chi-Square | NFI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Saturated Model | 0.058 | 10.889 | 22.857 | 25,476.43 | 0.962 |

| Independent Variable | Direct Effect | Indirect Effect | Total Effect | VAR Range | Mediation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entrepreneurial Orientation | 0.116 | 0.090 | 0.105 | 0.859 | Full |

| Independent Variable | Direct Effect | Indirect Effect | Total Effect | VAR Range | Mediation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entrepreneurial Orientation | 0.116 | 0.430 | 0.175 | 0.556 | Partial |

| Independent Variable | Direct Effect | Indirect Effect | Total Effect | VAR Range | Mediation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Innovation Types | 0.126 | 0.563 | 0.642 | 0.869 | Full |

| Hypothesis | Path Relations | Beta | Standard Error | t-Value | p-Values | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H7 | EO -> IP -> EP | 0.430 | 0.030 | 14.333 | 0.001 | Supported |

| H8 | EO -> IT -> EP | 0.090 | 0.039 | 2.292 | 0.024 | Supported |

| H9 | IT -> IP -> EP | 0.563 | 0.058 | 9.663 | 0.000 | Supported |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, Z.; Anaba, O.A.; Ma, Z.; Li, M. Ghanaian SMEs Amidst the COVID-19 Pandemic: Evaluating the Influence of Entrepreneurial Orientation. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1131. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13031131

Li Z, Anaba OA, Ma Z, Li M. Ghanaian SMEs Amidst the COVID-19 Pandemic: Evaluating the Influence of Entrepreneurial Orientation. Sustainability. 2021; 13(3):1131. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13031131

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Zhiwen, Oswin Aganda Anaba, Zhiqiang Ma, and Mingxing Li. 2021. "Ghanaian SMEs Amidst the COVID-19 Pandemic: Evaluating the Influence of Entrepreneurial Orientation" Sustainability 13, no. 3: 1131. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13031131

APA StyleLi, Z., Anaba, O. A., Ma, Z., & Li, M. (2021). Ghanaian SMEs Amidst the COVID-19 Pandemic: Evaluating the Influence of Entrepreneurial Orientation. Sustainability, 13(3), 1131. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13031131