The Hospice as a Learning Environment: A Follow-Up Study with a Palliative Care Team

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

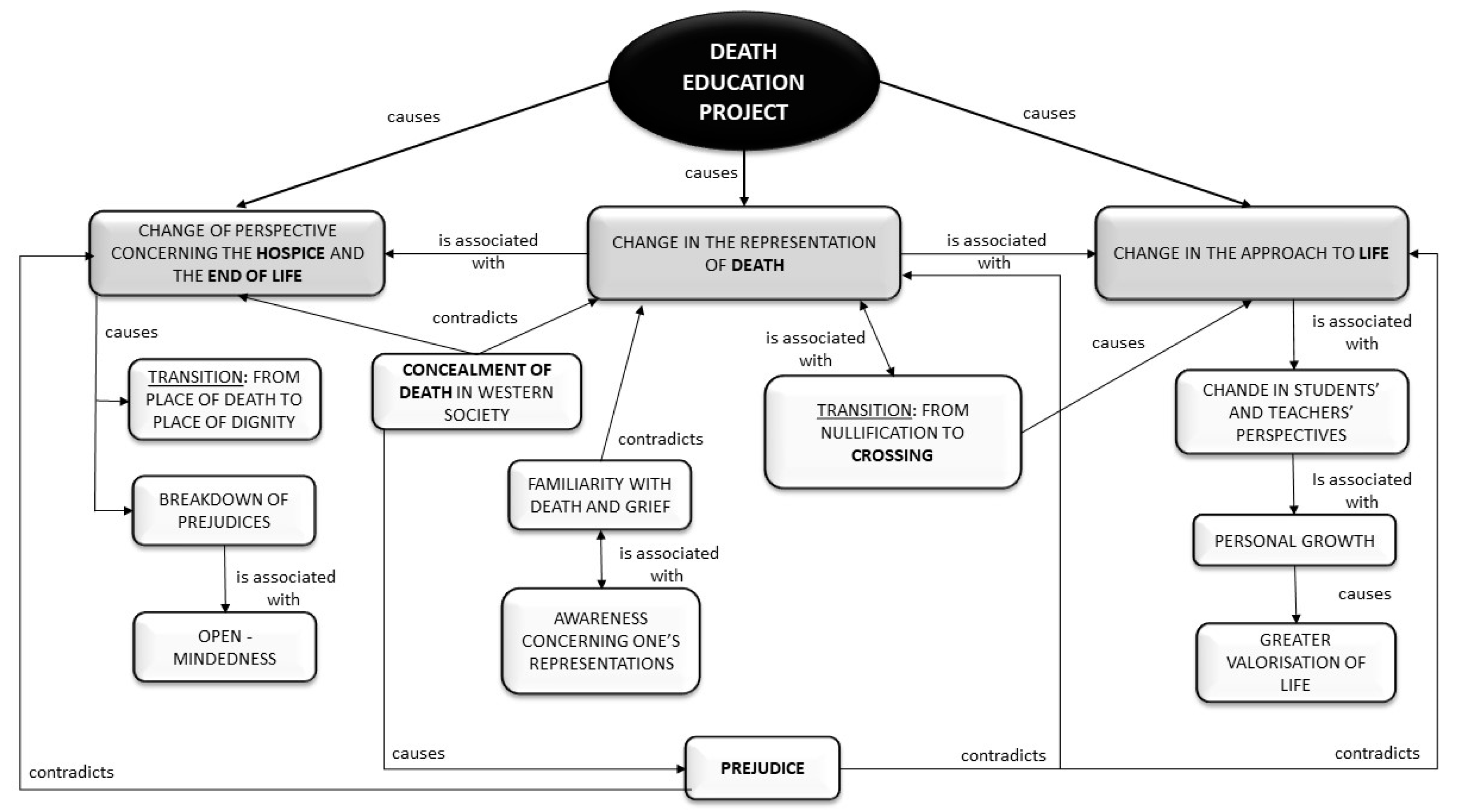

3.1. Thematic Area 1: Changes Following the Death Education Initiative

“The death education course allowed me, in the first place, to examine the ontological representations I had concerning death and, while reflecting upon them, to modify the most distressing ones. Initially, I saw death as something to avoid, something I preferred not to think about, that I preferred to cast aside, and now, instead, I am able to face the idea of death in a calmer way, I am able to speak about it, to mention it; I am able to accept death as, indeed, the conclusion of a path that is part of life. This allows me to act as a support for the patients’ relatives in the hospice and also as a support for my own relatives and friends.”

“The general fear was of entering a sort of “factory of death”. When I proposed to visit the hospice, the students were full of prejudices that certainly came from what we, as adults, communicate to them, from the way we talk about the hospice in our society.”

3.2. Thematic Area 2: Usefulness of Death Education for Elaborating the Community’s Traumatic Grief

“There is a huge difference between being silent, as often happens after a suicide, and being able to talk about it, considering death as something natural. In the latter case, the elaboration of grief helps people to draw on the resources they need to face the situation and the distress without isolating themselves … on the contrary, talking about grief at the community level offers support to all.”

“Talking about death can make us reflect upon the fact that death is part of life and that it is therefore not something obscene but rather something that is natural. It is important to intervene with a philosophical reflection concerning life, considering it as a good that is not endless, but, on the contrary, available for a limited amount of time.”

“Death education is useful because it means going back to our origins; in the past, indeed, when there wasn’t a very sophisticated health network, these efforts to accompany people facing death were conducted at home, and therefore there was much more solidarity. A communitarian path would help us rediscover what we already have inside of us, that is, the importance of accompanying a person right until his/her last instant of life. Thanks to these death education courses, there is a more welcoming atmosphere in the hospice, and the sense of responsibility towards the patients and their families has increased because we now operate in a cultural environment that needs to seriously deepen its engagement with the themes of death.”

3.3. Thematic Area 3: Motivations to Reintroduce the Death Education Initiative

“Yes, all well and good, but I would like to stress more that here in the hospice, we were all amazed at the maturity shown by the students. They showed great depth of thought in their discussions with us, despite their young age, and this is important because it means that they really think about death even though no one seriously talks to them about it, and this course permitted them to reflect on this issue in a more profound way.”

“Yes, I absolutely agree, but I want to make some additions. It is very important to affirm that all the schools should implement death education courses, inserting them into the educational system in a structural and interdisciplinary way. In fact, I do not believe that only spiritual dimensions can help to manage death. Indeed, there are spiritual texts of great importance, but also theatrical, musical and pictorial works. Art also helps to manage anguish. We all need good and beautiful readings that enrich our language and our ability to attach words to our experiences of loss and mortality.”

“I agree with everything, but now that I have the chance, I feel I still have something to express. The project has highlighted the relationship between love and death. Yes, love is what allows us to live, but it is also what allows us to face the passage of death. Without love, death is unbearable. The project has therefore enhanced love and this aspect must be highlighted. I believe that the students understood, first and foremost, that those who do not love are already dead, while those who love do not die. This is the synthesis of what we all understood together.”

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Limitations of the Study

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Testoni, I.; Piscitello, M.; Ronconi, L.; Zsák, É.; Iacona, E.; Zamperini, A. Death Education and the Management of Fear of Death Via Photo-Voice: An Experience Among Undergraduate Students. J. Loss Trauma 2019, 5–6, 387–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, S.; Testoni, I.; Bianco, S. Clash of civilizations? Terror management theory and the role of the ontological representations of death in contemporary global crisis. Test. Psychom. Methodol. Appl. Psychol. 2017, 24, 379–398. [Google Scholar]

- Testoni, I.; Visintin, E.P.; Capozza, D.; Carlucci, M.C.; Shams, M. The implicit image of God: God as reality and psychological well-being. J. Sci. Study Relig. 2016, 55, 174–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testoni, I.; Bingaman, K.; Gengarelli, G.; Capriati, M.; De Vincenzo, C.; Toniolo, A.; Marchica, B.; Zamperini, A. Self-Appropriation between Social Mourning and Individuation: A Qualitative Study on Psychosocial Transition among Jehovah’s Witnesses. Pastor. Psychol. 2019, 68, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Codato, M.; Shaver, P.R.; Testoni, I.; Ronconi, L. Civic and moral disengagement, weak personal beliefs and unhappiness: A survey study of the “famiglia lunga” phenomenon in Italy. TPM Test. Psychom. Methodol. Appl Psychol. 2011, 18, 87–97. [Google Scholar]

- Berry, P.; Wernick, A. (Eds.) Shadow of Spirit: Postmodernism and Religion; Routledge: London, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Testoni, I.; Lazzarotto Simioni, J.; Di Lucia Sposito, D. Representation of death and social management of the limit of life: Between resilience and irrationalism. Nutr. Metab. 2013, 31, 192–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testoni, I.; Facco, E.; Perelda, F. Toward A New Eternalist Paradigm for Afterlife Studies: The Case of the Near-Death Experiences Argument. World Futures 2017, 73, 442–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batista, A.S.; Wanderley, C. Dirty Work and Stigma: Caretakers of Death in Cemeteries. Rev. Estud. Soc. 2018, 63, 72–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, S.B.; Grandy, G. Stigmas, Work and Organizations; Springer: Basingstoke, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, W.E. Handling the stigma of handling the dead: Morticians and funeral directors. Deviant Behav. 1991, 12, 403–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, M.J.; Wellman, J.D. Evidence of palliative care stigma: The role of negative stereotypes in preventing willingness to use palliative care. Palliat. Supportive Care 2019, 17, 374–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherny, N.I. Stigma associated with “palliative care” getting around it or getting over it. Cancer 2009, 115, 1808–1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmermann, C.I. 6 Stigma Around Palliative Care: Why It Exists and How to Manage It. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2019, 14, S1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.X.; Chen, T.J.; Lin, M.H. Branding Palliative Care Units by Avoiding the Terms “Palliative” and “Hospice” A Nationwide Study in Taiwan. INQUIRY J. Health Care Organ. Provis. Financ. 2017, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentein, K.; Garcia, A.; Guerrero, S.; Herrbach, O. How does social isolation in a context of dirty work increase emotional exhaustion and inhibit work engagement? A process model. Pers. Rev. 2017, 46, 1620–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashforth, B.E.; Kreiner, G.E.; Clark, M.A.; Fugate, M. Congruence work in stigmatized occupations: A managerial lens on employee fit with dirty work. J. Organ. Behav. 2017, 38, 1260–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sardiwalla, N.; VandenBerg, H.; Esterhuyse, K.G.F. The Role of Stressors and Coping Strategies in the Burnout Experienced by Hospice Workers. Cancer Nurs. 2007, 30, 488–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schimel, J.; Hayes, J.; Williams, T.; Jahrig, J. Is death really the worm at the core? Converging evidence that worldview threat increases death-thought accessibility. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 92, 789–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testoni, I.; Cordioli, C.; Nodari, E.; Zsak, E.; Marinoni, G.L.; Venturini, D.; Maccarini, A. Language re-discovered: A death education intervention in the net between kindergarten, family and territory. Ital. J. Sociol. Educ. 2019, 11, 331–346. [Google Scholar]

- Testoni, I.; Sansonetto, G.; Ronconi, L.; Rodelli, M.; Baracco, G.; Grassi, L. Meaning of life, representation of death, and their association with psychological distress. Palliat. Supportive Care 2018, 16, 511–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testoni, I.; Parise, G.; Zamperini, A.; Visintin, E.P.; Toniolo, E.; Vicentini, S.; De Leo, D. The “sick-lit” question and the death education answer. Papageno versus Werther effects in adolescent suicide prevention. Hum. Aff. (Bratsil) 2016, 26, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durlak, J.A.; Riesenberg, L.A. The impact of death education. Death Stud. 1991, 15, 39–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowton, K.; Higginson, I.J. Managing bereavement in the classroom: A conspiracy of silence? Death Stud. 2003, 27, 717–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Pratt, C.C.; Hare, J.; Wright, C. Death and dying in early childhood education: Are educators prepared? Education 2001, 107, 279–286. [Google Scholar]

- McClatchey, I.S.; King, S. The Impact of Death Education on Fear of Death and Death Anxiety among Human Services Students. OMEGA (Westport.) 2015, 71, 343–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doka, K.J. Hannelore Wass: Death Education-An Enduring Legacy. Death Stud. 2015, 39, 545–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Testoni, I.; Biancalani, G.; Ronconi, L.; Varani, S. Let’s Start with the End: Bibliodrama in an Italian Death Education Course on Managing Fear of Death, Fantasy-Proneness, and Alexithymia with a Mixed-Method Analysis. OMEGA (Westport.) 2019, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Successful Qualitative Research: A Practical Guide for Beginners; Sage: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wass, H. A perspective on the current state of death education. Death Stud. 2004, 28, 289–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, W.Y. The Growth of Death Awareness through Death Education among University Students in Hong Kong. OMEGA J. Death Dying 2009, 59, 113–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neimeyer, R.A. Meaning Reconstruction and the Experience of Loss; American Psychological Association: Whashington, DC, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Kastenbaum, R. Death, Society, and Human Experience, 11th ed.; Allun & Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Waas, H. Death education for children. In Dying, Death, and Bereavement; Corless, I., Germino, B.B., Pittman, M.A., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2003; pp. 25–41. [Google Scholar]

- Thieleman, K.; Cacciatore, J. “Experiencing life for the first time”: The effects of a traumatic death course on social work student mindfulness and empathy. Soc. Work Educ. 2018, 38, 470–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testoni, I.; Iacona, E.; Fusina, S.; Floriani, M.; Crippa, M.; Maccarini, A.; Zamperini, A. “Before I die I want to…”: An experience of death education among university students of social service and psychology. Health Psychol. Open. 2018, 5, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aseltine, R.H.; James, A.; Schilling, E.A.; Glanovsky, J. Evaluating the SOS suicide prevention program: A replication and extension. BMC Public Health 2007, 7, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Testoni, I.; Ronconi, L.; Palazzo, L.; Galgani, M.; Stizzi, A.; Kirk, K. Psychodrama and moviemaking in a death education course to work through a case of suicide among high school students in Italy. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Testoni, I.; Ronconi, L.; Cupit, I.N.; Nodari, E.; Bormolini, G.; Ghinassi, A.; Messeri, D.; Cordioli, C.; Zamperini, A. The effect of death education on fear of death amongst Italian adolescents: A nonrandomized controlled study. Death Stud. 2019, 44, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corr, C.A. Teaching About Life and Living in Courses on Death and Dying. OMEGA (Westport.) 2016, 73, 174–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss, A.; Corbin, J. Grounded Theory Methodology: An Overview. In Handbook of Qualitative Research, 1st ed.; Denzin, N., Lincoln, Y., Eds.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994; pp. 273–284. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser, B.G.; Strauss, A.L. The Discovery of Grounded Theory, 1st ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Thematic analysis. In APA Handbook of Research Methods in Psychology, Vol 2: Research Designs: Quantitative, Qualitative, Neuropsychological, and Biological; Cooper, H., Camic, P.M., Long, D.L., Panter, A.T., Rindskopf, D., Sher, K.J., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2012; pp. 57–71. [Google Scholar]

- Muhr, T. ATLAS/ti—A prototype for the support of text interpretation. Qual. Sociol. 1991, 14, 349–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, V.; Braun, V. Thematic analysis. In Encyclopedia of Critical Psychology; Teo, T., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 1947–1952. [Google Scholar]

- Nowell, L.S.; Norris, J.M.; White, D.E.; Moules, N.J. Thematic analysis: Striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2017, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testoni, I.; Bisceglie, D.; Ronconi, L.; Pergher, V.; Facco, E. Ambivalent trust and ontological representations of death as latent factors of religiosity. Cogent Psychol. 2018, 5, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamino, L. ADEC at 40: Second half of life wisdom for the future of death education and counseling. Death Stud. 2017, 41, 188–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terskova, M.A.; Agadullina, E.R. Dehumanization of dirty workers and attitude towards social support. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2019, 49, 767–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malone, P.A. Counseling Adolescents through Loss, Grief and Trauma; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Gould, M.S.; Lake, A.M.; Kleinman, M.; Galfalvy, H.; Chowdhury, S.; Madnick, A. Exposure to Suicide in High Schools: Impact on Serious Suicidal Ideation/Behavior, Depression, Maladaptive Coping Strategies, and Attitudes toward Help-Seeking. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2018, 15, 455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asgari, Z.; Naghavi, A. Experience of Adolescents’ Post Traumatic Growth after Sudden Loss of Father. J. Loss Trauma 2020, 25, 173–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heath, M.A.; Cole, B.V. Strengthening Classroom Emotional Support for Children Following a Family Member’s Death. Sch. Psychol. Int. 2012, 33, 243–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roepke, A.M. Psychosocial interventions and posttraumatic growth: A meta-analysis. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2015, 83, 129–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedeschi, R.G.; Calhoun, L.G. Posttraumatic Growth: Conceptual Foundations and Empirical Evidence. Psychol. Inq. 2004, 15, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lima, R.; Brito Bergold, L.; de Souza, J.D.F.; Genesis, B.; Ferreira, M. Death education: Sensibility for caregiving. Rev. Bras Enferm. 2018, 71, 1779–1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Case, D.M.; Cheah, W.H.; Liu, M. “Mourning with the Morning Bell”: An Examination of Secondary Educators’ Attitudes and Experiences in Managing the Discourse of Death in the Classroom. OMEGA (Westport.) 2020, 80, 397–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacciatore, J.; Thieleman, K.; Killian, M.; Tavasolli, K. Braving Human Suffering: Death Education and its Relationship to Empathy and Mindfulness. Soc. Work Educ. 2015, 34, 91–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Formaini, J. Discovering Hannelore Wass. Death Stud. 2015, 39, 553–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spicer, S.; Heller, R.; Troth, S. Hospice clinical experiences for nursing students: Living to the fullest. J Christ. Nurs. 2015, 32, 46–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dadfar, M.; Farid, A.A.A.; Lester, D.; Vahid, M.; Kazem, A.; Birashk, B. Effectiveness of death education program by methods of didactic, experiential and 8A model on the reduction of death distress among nurses. Int. J. Med. Res. Health Sci. 2016, 5, 60–71. [Google Scholar]

- Lippen, M.P.; Becker, H. Improving Attitudes and Perceived Competence in Caring for Dying Patients: An End-of-Life Simulation. Nurs. Educ. Perspect. 2015, 36, 372–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Testoni, I.; Tronca, E.; Biancalani, G.; Ronconi, L.; Calapai, G. Beyond the wall: Death education at middle school as suicide prevention. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Testoni, I.; Palazzo, L.; de Vincenzo, C.; Wieser, M.A. Enhancing existential thinking through death education: A qualitative study among high school students. Behav. Sci. 2020, 10, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piotrowski, J.P.; Żemojtel-Piotrowska, M.; Clinton, A. Spiritual transcendence as a buffer against death anxiety. Curr. Psychol. 2020, 39, 994–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jong, J.; Bluemke, M.; Halberstadt, J. Fear of death and supernatural beliefs: Developing a new Supernatural Belief Scale to test the relationship. Eur. J. Personal. 2013, 27, 495–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dechesne, M.; Pyszczynski, T.; Arndt, J.; Ransom, S.; Sheldon, K.M.; van Knippenberg, A.; Janssen, J. Literal and symbolic immortal-ity: The effect of evidence of literal immortality on self-esteem strivingin response to mortality salience. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 84, 722–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Routledge, C.; Arndt, J. Self-sacrifice as self-defense: Mortality salience increases efforts to affirm a symbolic immortal self at the expense of the physical self. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2008, 38, 531–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heflick, N.A.; Goldenberg, J.L. No atheists in foxholes: Arguments for (but not against) afterlife belief buffers mortality salience effects for atheists. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 51, 385–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, S.; Greenberg, J.; Pyszczynski, T. The Worm at the Core. On the Role of Death in Life; Random House: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

| Age | Sex | Qualification | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| μ | σ | Female | Male | High School Diploma | University Degree | |

| School (n = 9) | 53.11 | 10.2 | 6 | 3 | - | 9 |

| Hospice (n = 11) | 44 | 5.98 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 7 |

| Total (n = 20) | 48.1 | 9.18 | 12 | 8 | 4 | 16 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Testoni, I.; Sblano, V.F.; Palazzo, L.; Pompele, S.; Wieser, M.A. The Hospice as a Learning Environment: A Follow-Up Study with a Palliative Care Team. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7460. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17207460

Testoni I, Sblano VF, Palazzo L, Pompele S, Wieser MA. The Hospice as a Learning Environment: A Follow-Up Study with a Palliative Care Team. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(20):7460. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17207460

Chicago/Turabian StyleTestoni, Ines, Vito Fabio Sblano, Lorenza Palazzo, Sara Pompele, and Michael Alexander Wieser. 2020. "The Hospice as a Learning Environment: A Follow-Up Study with a Palliative Care Team" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 20: 7460. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17207460

APA StyleTestoni, I., Sblano, V. F., Palazzo, L., Pompele, S., & Wieser, M. A. (2020). The Hospice as a Learning Environment: A Follow-Up Study with a Palliative Care Team. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(20), 7460. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17207460