Sustainable vs. Unsustainable Food Consumption Behaviour: A Study among Students from Romania, Bulgaria and Moldova

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Material and Method

3. Research Findings

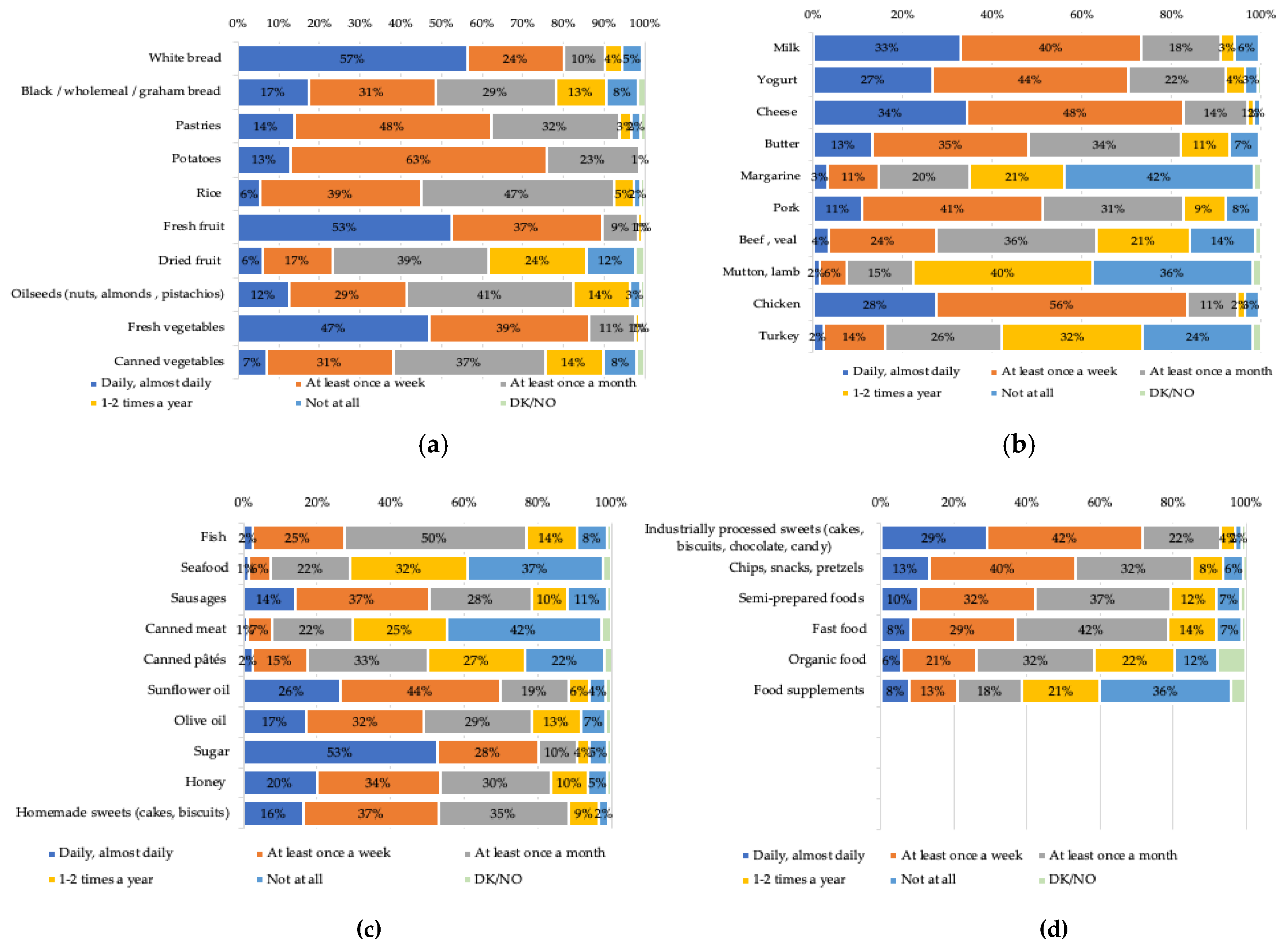

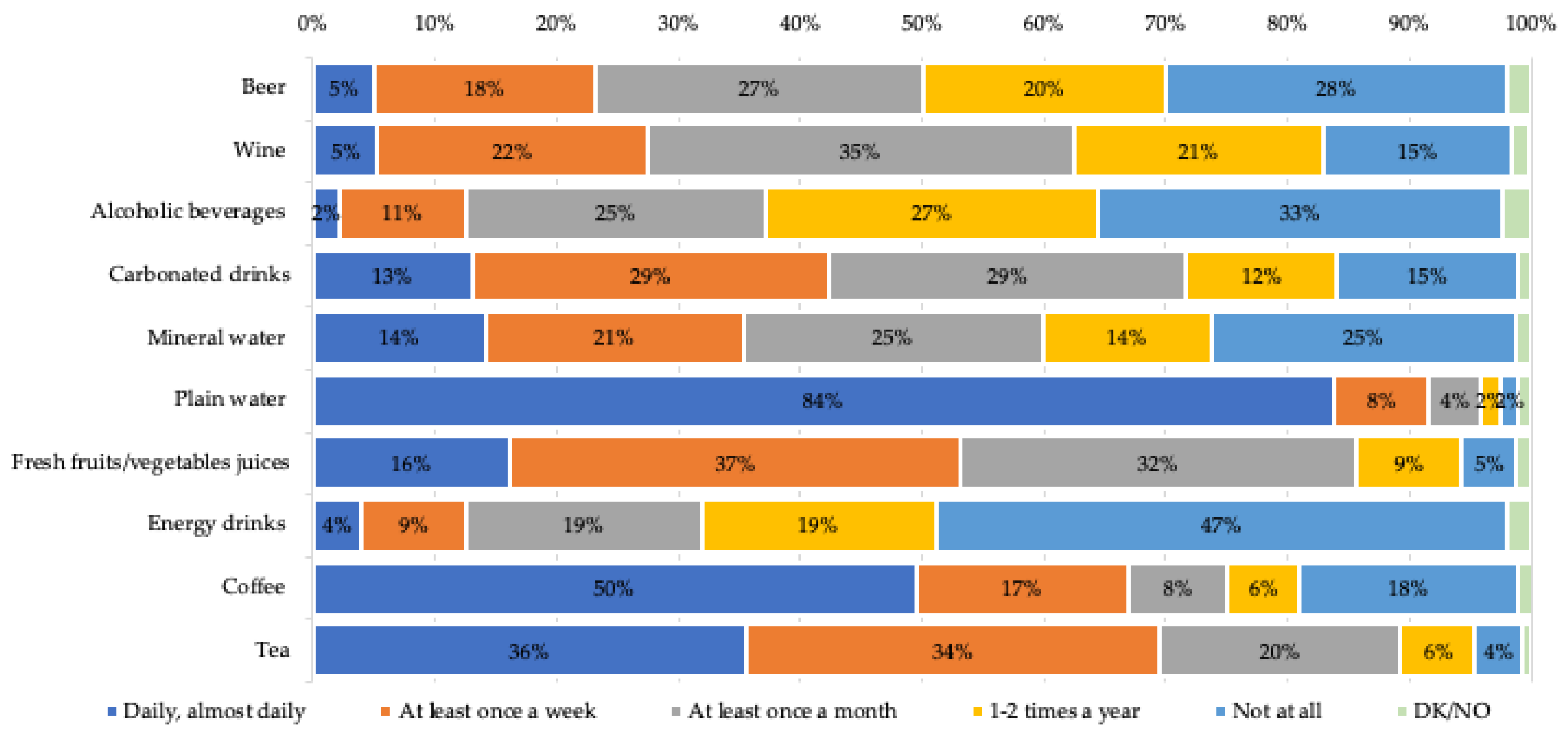

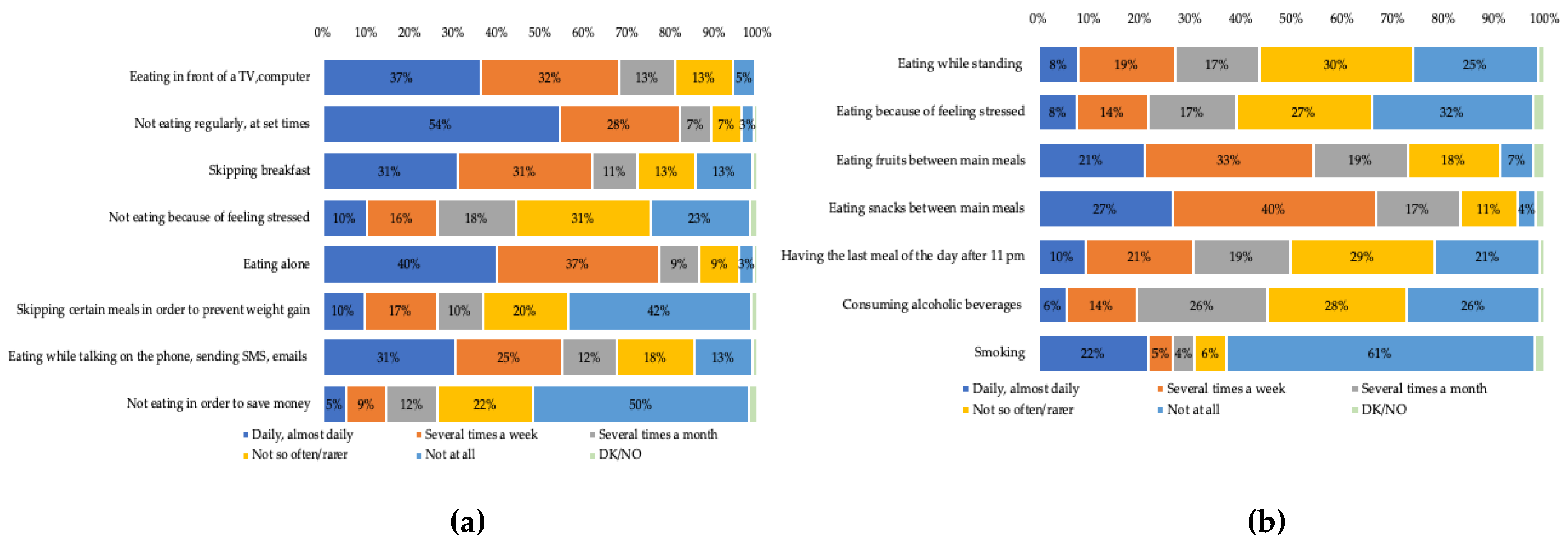

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

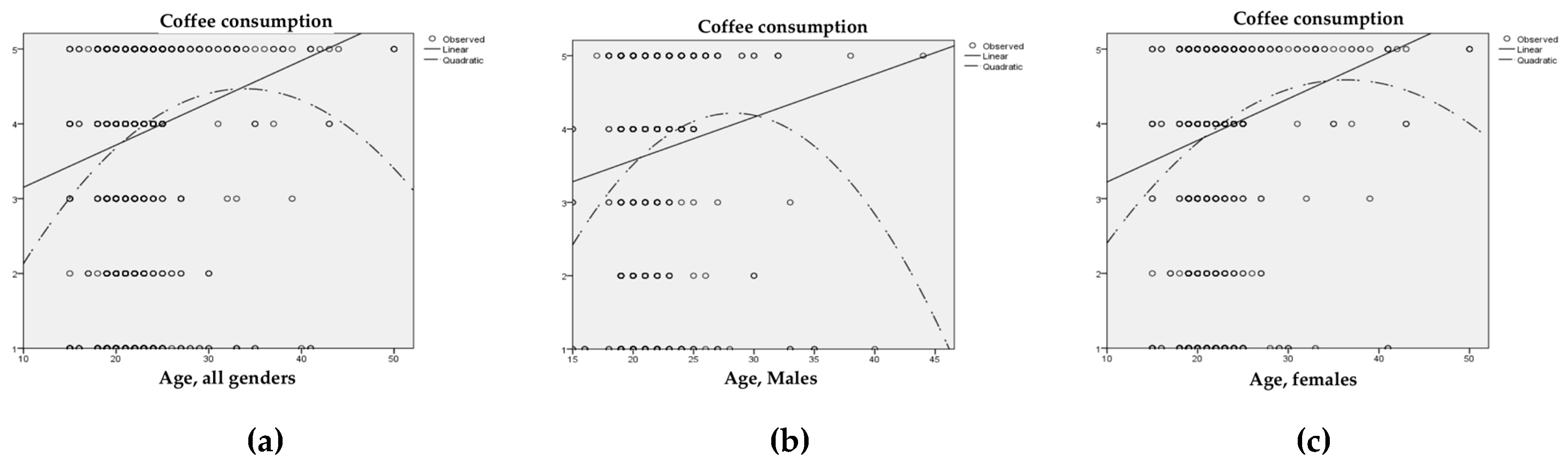

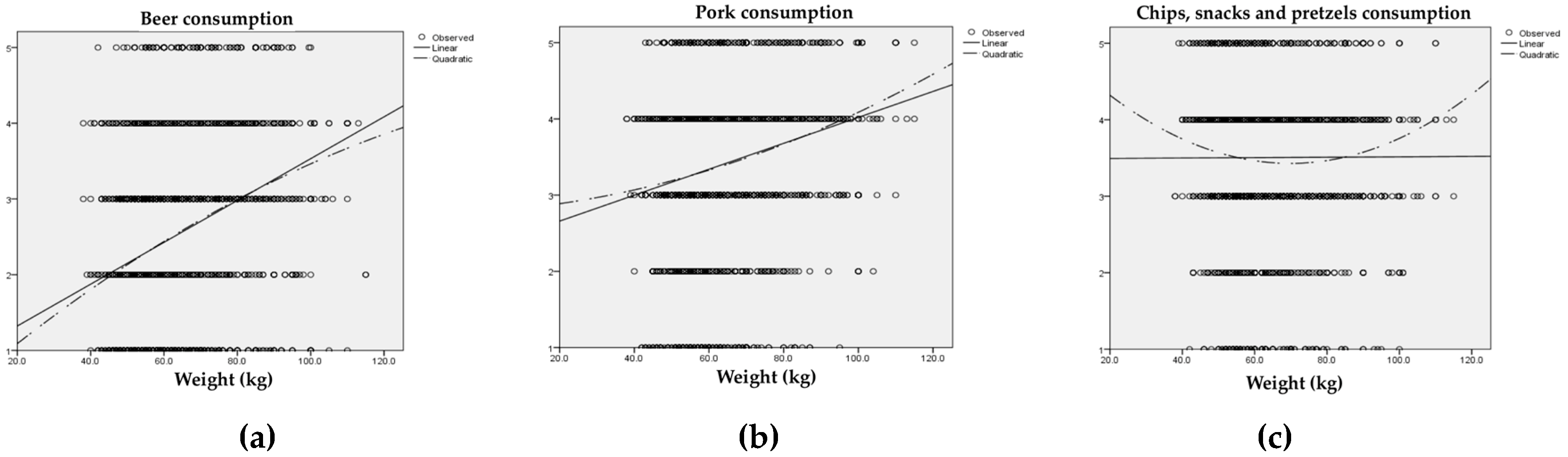

3.2. Inferential Statistics

4. Discussions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jacobs, C.; Berglund, M.; Kurnik, B.; Dworak, T.; Marras, S.; Mereu, V.; Michetti, M. Climate Change Adaptation in the Agriculture Sector in Europe; EEA Report: 4/2019; European Environment Agency (EEA): Luxembourg, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie, H. Food Production Is Responsible for One-Quarter of the World’s Greenhouse Gas Emissions—Our World in Data. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/food-ghg-emissions (accessed on 21 May 2020).

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Environment Statistics. The Contribution of Agriculture to Greenhouse Gas Emissions. Available online: http://www.fao.org/economic/ess/environment/data/emission-shares/en/ (accessed on 21 May 2020).

- Ritchie, H. Food Waste Is Responsible for 6% of Global Greenhouse Gas Emissions—Our World in Data. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/food-waste-emissions (accessed on 21 May 2020).

- Sustainable Food-Environment-European Commission. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/environment/archives/eussd/food.htm (accessed on 24 April 2020).

- Reisch, L.; Eberle, U.; Lorek, S. Sustainable food consumption: An overview of contemporary issues and policies. Sustain. Sci. Pr. Policy 2013, 9, 7–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Sustainable Development Goals. Goal 12: Ensure Sustainable Consumption and Production Patterns. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-consumption-production/ (accessed on 24 April 2020).

- Verain, M.; Sijtsema, S.; Dagevos, H.; Antonides, G. Attribute segmentation and communication effects on healthy and sustainable consumer diet intentions. Sustainability 2017, 9, 743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrillo, C.; Milano, S.; Roveglia, P.; Scaffidi, C. Slow food’s contribution to the debate on the sustainability of the food system. In 148th Seminar of the EAAE “Does Europe Need a Food Policy?”; Slow Food International: Brussels, Belgium, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Vermeir, I.; Verbeke, W. Sustainable food consumption: Exploring the consumer “attitude-behavioral intention” gap. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2006, 19, 169–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.J.; Li, H. Sustainable consumption and life satisfaction. Soc. Indic. Res. 2011, 104, 323–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pingali, P. Policies for sustainable food systems. In Sustainable Food and Agriculture; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 509–521. [Google Scholar]

- Norwegian Ministry of the Environment. Oslo Roundtable on Sustainable Production and Consumption; Norwegian Ministry of the Environment: Oslo, Norway, 1994.

- Lim, E.; Arita, S.; Joung, S. Advancing sustainable consumption in Korea and Japan-from re-orientation of consumer behavior to civic actions. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baudry, J.; Péneau, S.; Allès, B.; Touvier, M.; Hercberg, S.; Galan, P.; Amiot, M.-J.; Lairon, D.; Méjean, C.; Kesse-Guyot, E. Food choice motives when purchasing in organic and conventional consumer clusters: Focus on sustainable concerns (the NutriNet-Santé cohort study). Nutrients 2017, 9, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Definition of “sustainable diets”. In Proceedings of the International Scientific Symposium “Biodiversity and Sustainable Diets: United against Hunger”, Rome, Italy, 3–5 November 2010; p. 10. [Google Scholar]

- Waxman, A. WHO global strategy on diet, physical activity and health. Food Nutr. Bull. 2004, 25, 292–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertens, E.; Van’T Veer, P.; Hiddink, G.J.; Steijns, J.M.; Kuijsten, A. Operationalising the health aspects of sustainable diets: A review. Public Health Nutr. 2017, 20, 739–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonides, G. Sustainable consumer behaviour: A collection of empirical studies. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollani, L.; Bonadonna, A.; Peira, G. The millennials’ concept of sustainability in the food sector. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aschemann-Witzel, J. Consumer perception and trends about health and sustainability: Trade-offs and synergies of two pivotal issues. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2015, 3, 6–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, S.; Noriega, B.R.; Shin, J.Y. College students’ eating habits and knowledge of nutritional requirements. J. Nutr. Hum. Heal. 2018, 2, 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrigan, M.; Attalla, A. The myth of the ethical consumer-do ethics matter in purchase behaviour? J. Consum. Mark. 2001, 18, 560–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Meyer-Höfer, M.; von der Wense, V.; Spiller, A. Characterising convinced sustainable food consumers. Br. Food J. 2015, 117, 1082–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verain, M.C.D.; Dagevos, H.; Antonides, G. Sustainable food consumption. Product choice or curtailment? Appetite 2015, 91, 375–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konttinen, H.; Sarlio-Lähteenkorva, S.; Silventoinen, K.; Männistö, S.; Haukkala, A. Socio-economic disparities in the consumption of vegetables, fruit and energy-dense foods: The role of motive priorities. Public Health Nutr. 2013, 16, 873–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giskes, K.; Turrell, G.; Patterson, C.; Newman, B. Socio-economic differences in fruit and vegetable consumption among Australian adolescents and adults. Public Health Nutr. 2002, 5, 663–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hupkens, C.L.H.; Knibbe, R.A.; Drop, M.J. Social class differences in food consumption. The explanatory value of permissiveness and health and cost considerations. Eur. J. Public Health 2000, 10, 108–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Irala-Estévez, J.; Groth, M.; Johansson, L.; Oltersdorf, U.; Prättälä, R.; Martínez-González, M.A. A systematic review of socio-economic differences in food habits in Europe: Consumption of fruit and vegetables. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2000, 54, 706–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allès, B.; Péneau, S.; Kesse-Guyot, E.; Baudry, J.; Hercberg, S.; Méjean, C. Food choice motives including sustainability during purchasing are associated with a healthy dietary pattern in French adults. Nutr. J. 2017, 16, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowman, S.A. A comparison of the socioeconomic characteristics, dietary practices, and health status of women food shoppers with different food price attitudes. Nutr. Res. 2006, 26, 318–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guthrie, J.; Mancino, L.; Lin, C.-T.J. Nudging consumers toward better food choices: Policy approaches to changing food consumption behaviors. Psychol. Mark. 2015, 32, 501–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, J.C.; Netemeyer, R.G.; Burton, S. The nutrition elite: Do only the highest levels of caloric knowledge, obesity knowledge, and motivation matter in processing nutrition ad claims and disclosures? J. Public Policy Mark. 2009, 28, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, O.N.; O’Connor, L.E.; Savaiano, D. Mobile MyPlate: A pilot study using text messaging to provide nutrition education and promote better dietary choices in college students. J. Am. Coll. Heal. 2014, 62, 320–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boucher, D.; Gagné, C.; Côté, F. Effect of an intervention mapping approach to promote the consumption of fruits and vegetables among young adults in junior college: A quasi-experimental study. Psychol. Heal. 2015, 30, 1306–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Cauwenberghe, E.; Maes, L.; Spittaels, H.; Van Lenthe, F.J.; Brug, J.; Oppert, J.M.; De Bourdeaudhuij, I. Effectiveness of school-based interventions in Europe to promote healthy nutrition in children and adolescents: Systematic review of published and “grey” literature. Br. J. Nutr. 2010, 103, 781–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryła, P. The development of organic food market as an element of sustainable development concept implementation. Probl. Ekorozwoju Probl. Sustain. Dev. 2015, 10, 79–88. [Google Scholar]

- Vermeir, I.; Verbeke, W. Sustainable food consumption among young adults in Belgium: Theory of planned behaviour and the role of confidence and values. Ecol. Econ. 2008, 64, 542–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson-O’Brien, R.; Larson, N.; Neumark-Sztainer, D.; Hannan, P.; Story, M. Characteristics and dietary patterns of adolescents who value eating locally grown, organic, nongenetically engineered, and nonprocessed food. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2009, 41, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisinger-Watzl, M.; Wittig, F.; Heuer, T.; Hoffmann, I. Customers purchasing organic food-do they live healthier? Results of the German national nutrition survey II. Eur. J. Nutr. Food Saf. 2015, 5, 59–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annunziata, A.; Mariani, A. Consumer perception of sustainability attributes in organic and local food. Recent Pat. Food. Nutr. Agric. 2018, 9, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vecchio, R.; Annunziata, A. Consumers’ attitudes towards sustainable food: A cluster analysis of Italian university students. New Medit 2013, 12, 47–56. [Google Scholar]

- Savelli, E.; Murmura, F.; Liberatore, L.; Casolani, N.; Bravi, L. Consumer attitude and behaviour towards food quality among the young ones: Empirical evidences from a survey. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excel. 2019, 30, 169–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamenidou, I.C.; Mamalis, S.A.; Pavlidis, S.; Bara, E.-Z.G. Segmenting the generation Z cohort university students based on sustainable food consumption behavior: A preliminary study. Sustainability 2019, 11, 837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stok, F.; Renner, B.; Clarys, P.; Lien, N.; Lakerveld, J.; Deliens, T. Understanding eating behavior during the transition from adolescence to young adulthood: A literature review and perspective on future research directions. Nutrients 2018, 10, 667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bădescu, G.; Uslaner, E.M. Social Capital and the Transition to Democracy; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- El Ansari, W.; Stock, C.; Mikolajczyk, R.T. Relationships between food consumption and living arrangements among university students in four European countries—A cross-sectional study. Nutr. J. 2012, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pocol, C.B.; Bența, I.; Ciobanu, E.; Cozma-Petruț, A.; Crețu-Stuparu, M.; Croitoru, C.; Marinescu, V.; Mateva, N.; Moldavian-Teselios, C.; Stranț, M. Comportamentul de Consum Alimentar În Rândul Tinerilor, Raport de Cercetare, Project “Réseau Régional Francophone sur la Santé, la Nutrition et la Sécurité Alimentaire (SaIN)” Financed by AUF. 2018. Available online: https://www.auf.org/europe-centrale-orientale/ (accessed on 23 March 2020).

- Friel, S.; Barosh, L.J.; Lawrence, M. Towards healthy and sustainable food consumption: An Australian case study. Public Health Nutr. 2014, 17, 1156–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graur, M.; Mihai, B.; Botnariu, G.; Popescu, R.; Lăcătuşu, C.; Mihalache, L.; Răcaru, V.; Ciocan, M.; Colisnic, A.; Popa, A.; et al. Ghid Pentru Alimentaţia Sănătoasă; Performantica: Iași, Romania, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health-National Center of Public Health Protection (NCPHP); WHO Regional Office for Europe. Food-Based Dietary Guidelines in for Adults in Bulgaria; FAO: Sofia, Bulgaria, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Croitoru, C.; Ciobanu, E.; Bahnarel, I.; Burduniuc, O.; Cazacu-Stratu, A.; Cebanu, S.; Ciobanu, E.; Ferdohleb, A.; Fira-Mlădinescu, C.; Friptuleac, G.; et al. Ghid de Bune Practici: Alimentație Rațională, Siguranța Alimentelor Și Schimbarea Comportamentului Alimentar; USMF: Chișinău, Moldova, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Vilija, M.; Romualdas, M. Unhealthy food in relation to posttraumatic stress symptoms among adolescents. Appetite 2014, 74, 86–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bech-Larsen, T.; Kazbare, L. Spillover of diet changes on intentions to approach healthy food and avoid unhealthy food. Health Educ. 2014, 114, 367–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visram, S.; Cheetham, M.; Riby, D.M.; Crossley, S.J.; Lake, A.A. Consumption of energy drinks by children and young people: A rapid review examining evidence of physical effects and consumer attitudes. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e010380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehlers, A.; Marakis, G.; Lampen, A.; Hirsch-Ernst, K.I. Risk assessment of energy drinks with focus on cardiovascular parameters and energy drink consumption in Europe. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2019, 130, 109–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lang, T.; Barling, D. Nutrition and sustainability: An emerging food policy discourse. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2013, 72, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Health Council of the Netherland. Guidelines for a Healthy Diet: The Ecological Perspective|Advisory Report|The Health Council of the Netherlands; Health Council of the Netherland: Hague, The Netherlands, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Westhoek, H.; Lesschen, J.P.; Rood, T.; Wagner, S.; De Marco, A.; Murphy-Bokern, D.; Leip, A.; van Grinsven, H.; Sutton, M.A.; Oenema, O. Food choices, health and environment: Effects of cutting Europe’s meat and dairy intake. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2014, 26, 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmadfa, I.; Meyer, A.; Nowak, V.; Hasenegger, V.; Putz, P.; Verstraeten, R.; Remaut-DeWinter, A.A.M.; Kolsteren, P.; Dostálová, J. European Nutrition and Health Report 2009, 62nd ed.; Elmadfa, I., Ed.; Karger: Basel, Switzerland, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Comparative Analysis of Nutrition Policies in the WHO European Region: A Comparative Analysis of Nutrition Policies and Plans of Action in WHO European Region; WHO: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Dagevos, H.; Voordouw, J. Sustainability and meat consumption: Is reduction realistic? Sustain. Sci. Pr. Policy 2013, 9, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, K.; Saunders, A.; Zeuschner, C. Chapter 8. red meat and health: Evidence regarding red meat, health, and chronic disease risk. In Impact of Meat Consumption on Health and Environmental Sustainability; Raphaely, A., Marinova, D., Eds.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2015; p. 131. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Diet, Nutrition, and the Prevention of Chronic Diseases: Report of a Joint WHO/FAO Expert Consultation; WHO Technical Report Series 916; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Perignon, M.; Vieux, F.; Soler, L.-G.; Masset, G.; Darmon, N. Improving diet sustainability through evolution of food choices: Review of epidemiological studies on the environmental impact of diets. Nutr. Rev. 2017, 75, 2–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poobalan, A.S.; Aucott, L.S.; Clarke, A.; Smith, W.C.S. Diet behaviour among young people in transition to adulthood (18–25 year olds): A mixed method study. Heal. Psychol. Behav. Med. 2014, 2, 909–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernardo, G.L.; Jomori, M.M.; Fernandes, A.C.; da Proença, R.P.C. Food intake of university students. Rev. Nutr. 2017, 30, 847–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birt, C.; Buzeti, T.; Grosso, G.; Justesen, L.; Lachat, C.; Lafranconi, A.; Mertanen, E.; Rangelov, N.; Sarlio-Lähteenkorva, S. Healthy and Sustainable Diets for European Countries; European Public Health Association: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- MacDiarmid, J.I. Is a healthy diet an environmentally sustainable diet? Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2013, 72, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salameh, P.; Jomaa, L.; Issa, C.; Farhat, G.; Salamé, J.; Zeidan, N.; Baldi, I.; Barbour, B.; Waked, M.; Zeghondi, H.; et al. Assessment of dietary intake patterns and their correlates among university students in Lebanon. Front. Public Heal. 2014, 2, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, S.L.; Vandelanotte, C.; Irwin, C.; Bellissimo, N.; Heidke, P.; Saluja, S.; Saito, A.; Khalesi, S. Association between dietary patterns and sociodemographics: A cross-sectional study of Australian nursing students. Nurs. Health Sci. 2019, 22, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resano, H.; Perez-Cueto, F.J.A.; de Barcellos, M.D.; Veflen-Olsen, N.; Grunert, K.G.; Verbeke, W. Consumer satisfaction with pork meat and derived products in five European countries. Appetite 2011, 56, 167–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stanford, L. Observations on alcohol beverage consumption. Aust. New Zeal. Wine Ind. J. 2000, 15, 14–27. [Google Scholar]

- Demura, S.; Aoki, H.; Mizusawa, T.; Soukura, K.; Noda, M.; Sato, T. Gender differences in coffee consumption and its effects in young people. Food Nutr. Sci. 2013, 4, 748–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, M.C.; Kocos, R.; Lytle, L.A.; Perry, C.L. Understanding the perceived determinants of weight-related behaviors in late adolescence: A qualitative analysis among college youth. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2009, 41, 287–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunes, F.E.; Bekiroglu, N.; Imeryuz, N.; Agirbasli, M. Relation between eating habits and a high body mass index among freshman students: A cross-sectional study. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2012, 31, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musaiger, A.O.; Radwan, H.M. Social and dietary factors associated with obesity in university female students in United Arab Emirates. J. R. Soc. Health 1995, 115, 96–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, P.R.M.; Luiz, R.R.; Monteiro, L.S.; Ferreira, M.G.; Gonçalves-Silva, R.M.V.; Pereira, R.A. Adolescents’ unhealthy eating habits are associated with meal skipping. Nutrition 2017, 42, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Striegel-Moore, R.H.; Franko, D.L.; Thompson, D.; Affenito, S.; Kraemer, H.C. Night eating: Prevalence and demographic correlates. Obesity 2006, 14, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiefer, I.; Rathmanner, T.; Kunze, M. Eating and dieting differences in men and women. J. Men’s Heal. Gend. 2005, 2, 194–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zellner, D.A.; Saito, S.; Gonzalez, J. The effect of stress on men’s food selection. Appetite 2007, 49, 696–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Górska-Warsewicz, H.; Rejman, K.; Laskowski, W.; Czeczotko, M. Butter, margarine, vegetable oils, and olive oil in the average polish diet. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lipovetsky, G.; Ungurean, M. Fericirea Paradoxală: Eseu Asupra Societății de Hiperconsum; Polirom: Iași, Romania, 2007. [Google Scholar]

| Gender | Age | Total | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | 18–19 Years Old | 20–21 Years Old | 22–23 Years Old | 24–25 Years Old | 26 Years Old+ | Don’t Know/ No Opinion | |||

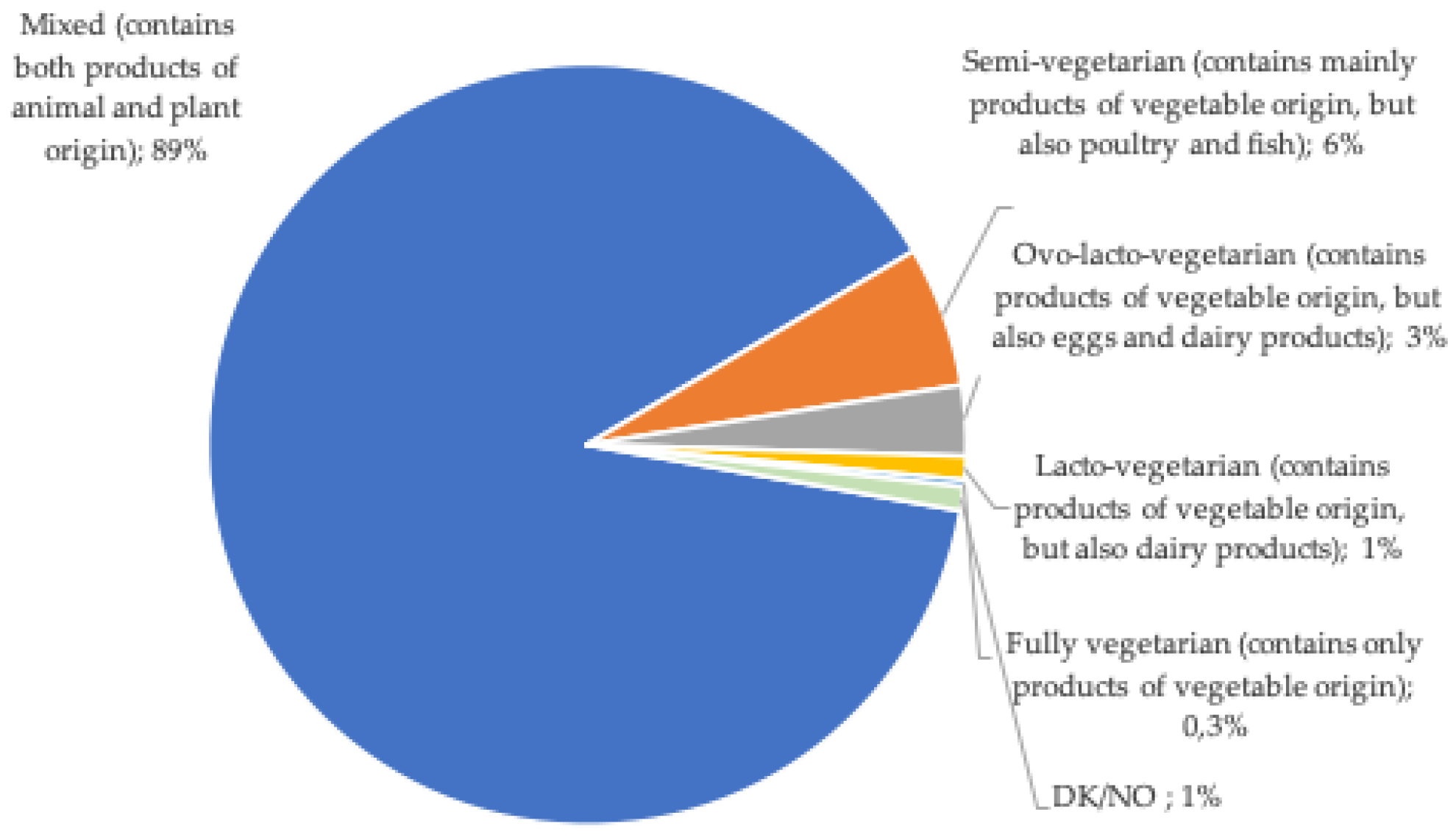

| What kind of diet do you usually have? | Mixed | 93.2% | 87.5% | 92.7% | 89.3% | 90.3% | 83.6% | 82.9% | 86.2% | 89.3% |

| Semi-vegetarian | 2.7% | 7.1% | 4.5% | 5.2% | 5.6% | 8.6% | 10.3% | 0.0% | 5.7% | |

| Ovo-lacto-vegetarian | 1.4% | 3.5% | 1.2% | 2.9% | 2.1% | 5.6% | 4.3% | 13.8% | 2.9% | |

| Lacto-vegetarian | 0.3% | 0.6% | 0.2% | 0.7% | 0.0% | 1.5% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.4% | |

| Vegetarian | 0.3% | 0.3% | 0.0% | 0.4% | 0.4% | 0.0% | 0.8% | 0.0% | 0.3% | |

| Don’t know/ No opinion | 2.1% | 1.0% | 1.4% | 1.5% | 1.6% | 0.7% | 1.7% | 0.0% | 14% | |

| Total | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | |

| Model | Unstandardised Coefficients | Standardised Coefficients | t | Sig. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Butter | 0.192 | 0.086 | 0.060 | 2.232 | 0.026 |

| Margarine | −0.169 | 0.075 | −0.060 | −2.248 | 0.025 |

| Pork meat | 0.237 | 0.093 | 0.073 | 2.564 | 0.010 |

| Canned meat | 0.291 | 0.095 | 0.087 | 3.055 | 0.002 |

| Canned pâtés | −0.234 | 0.088 | −0.074 | −2.660 | 0.008 |

| Sunflower oil | 0.244 | 0.087 | 0.075 | 2.794 | 0.005 |

| Industrially obtained sweets | −0.232 | 0.110 | −0.063 | −2.111 | 0.035 |

| Semi−prepared foods | −0.215 | 0.095 | −0.066 | −2.266 | 0.024 |

| Wine | 0.324 | 0.095 | 0.107 | 3.420 | 0.001 |

| Energy drinks | −0.234 | 0.078 | −0.083 | −3.003 | 0.003 |

| Coffee | 0.208 | 0.054 | 0.096 | 3.879 | 0.000 |

| Model | Unstandardised Coefficients | Standardised Coefficients | t | Sig. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I eat alone | −0.136 | 0.069 | −0.045 | −1.962 | 0.050 |

| I skip certain meals in order to prevent gaining weight | 0.116 | 0.059 | 0.050 | 1.972 | 0.049 |

| I eat while talking on the phone/sending SMS/emails | −0.201 | 0.055 | −0.088 | −3.664 | 0.000 |

| I do not eat in order to save money | −0.319 | 0.066 | −0.119 | −4.805 | 0.000 |

| I eat while standing | 0.282 | 0.062 | 0.110 | 4.534 | 0.000 |

| I have the last meal of the day after 23:00 | −0.225 | 0.062 | −0.089 | −3.599 | 0.000 |

| Model | Unstandardised Coefficients | Standardised Coefficients | t | Sig. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I do not have breakfast | 0.909 | 0.240 | 0.095 | 3.784 | 0.000 |

| I do not eat because I feel stressed | −1.897 | 0.246 | −0.182 | −7.696 | 0.000 |

| I skip certain meals in order to prevent gaining weight | 0.998 | 0.244 | 0.103 | 4.082 | 0.000 |

| I eat while talking on the phone/sending SMS/emails | −1.406 | 0.226 | −0.149 | −6.218 | 0.000 |

| I eat while standing | 1.058 | 0.257 | 0.099 | 4.114 | 0.000 |

| I have snacks between meals | −0.868 | 0.316 | −0.068 | −2.746 | 0.006 |

| I have the last meal of the day after 23:00 | 0.715 | 0.258 | 0.068 | 2.768 | 0.006 |

| Levene’s Test for Equality of Variances | t-test for Equality of Means | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | Sig. | t | df | Sig. (2-tailed) | Mean Difference | Std. Error Difference | 95% Confidence Interval of the Difference | |||

| Lower | Upper | |||||||||

| Industrially obtained sweets | Equal variances assumed | 0.388 | 0.533 | −2.609 | 2349 | 0.009 | −0.106 | 0.041 | −0.186 | −0.026 |

| Equal variances not assumed | −2.659 | 1478.000 | 0.008 | −0.106 | 0.040 | −0.185 | −0.028 | |||

| Semi−prepared foods | Equal variances assumed | 1.680 | 0.195 | 2.888 | 2341 | 0.004 | 0.133 | 0.046 | 0.043 | 0.223 |

| Equal variances not assumed | 2.965 | 1484.929 | 0.003 | 0.133 | 0.045 | 0.045 | 0.221 | |||

| Beer | Equal variances assumed | 0.359 | 0.549 | 19.936 | 2330 | 0.000 | 1.009 | 0.051 | 0.910 | 1.108 |

| Equal variances not assumed | 19.466 | 1320.280 | 0.000 | 1.009 | 0.052 | 0.907 | 1.111 | |||

| Frizzy drinks | Equal variances assumed | 0.981 | 0.322 | 10.047 | 2349 | 0.000 | 0.542 | 0.054 | 0.436 | 0.648 |

| Equal variances not assumed | 10.325 | 1511.803 | 0.000 | 0.542 | 0.053 | 0.439 | 0.645 | |||

| Coffee | Equal variances assumed | 1.188 | 0.276 | −2.691 | 2348 | 0.007 | −0.185 | 0.069 | −0.321 | −0.050 |

| Equal variances not assumed | −2.687 | 1397.216 | 0.007 | −0.185 | 0.069 | −0.321 | −0.050 | |||

| Levene’s Test for Equality of Variances | t-test for Equality of Means | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | Sig. | t | df | Sig. (2-tailed) | Mean Difference | Std. Error Difference | 95% Confidence Interval of the Difference | |||

| Lower | Upper | |||||||||

| I do not eat because I feel stressed | Equal variances assumed | 0.708 | 0.400 | −4.891 | 2336 | 0.000 | −0.281 | 0.057 | −0.393 | −0.168 |

| Equal variances not assumed | −4.853 | 1354.720 | 0.000 | −0.281 | 0.058 | −0.394 | −0.167 | |||

| I eat while standing | Equal variances assumed | 1.042 | 0.307 | 2.050 | 2343 | 0.041 | 0.116 | 0.057 | 0.005 | 0.228 |

| Equal variances not assumed | 2.035 | 1372.007 | 0.042 | 0.116 | 0.057 | 0.004 | 0.229 | |||

| I have snacks between meals | Equal variances assumed | 0.963 | 0.327 | −3.457 | 2333 | 0.001 | −0.167 | 0.048 | −0.262 | −0.072 |

| Equal variances not assumed | −3.461 | 1396.776 | 0.001 | −0.167 | 0.048 | −0.261 | −0.072 | |||

| I have the last meal of the day after 11 pm | Equal variances assumed | 3.786 | 0.052 | 9.525 | 2354 | 0.000 | 0.532 | 0.056 | 0.423 | 0.642 |

| Equal variances not assumed | 9.625 | 1433.008 | 0.000 | 0.532 | 0.055 | 0.424 | 0.641 | |||

| I consume alcoholic beverages | Equal variances assumed | 2.874 | 0.090 | 12.612 | 2350 | 0.000 | 0.643 | 0.051 | 0.543 | 0.743 |

| Equal variances not assumed | 12.322 | 1324.868 | 0.000 | 0.643 | 0.052 | 0.541 | 0.745 | |||

| Levene’s Test for Equality of Variances | t-test for Equality of Means | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | Sig. | t | df | Sig. (2-tailed) | Mean Difference | Std. Error Difference | 95% Confidence Interval of the Difference | |||

| Lower | Upper | |||||||||

| Butter | Equal variances assumed | 3.690 | 0.055 | 2.957 | 2331 | 0.003 | 0.139 | 0.047 | 0.047 | 0.230 |

| Equal variances not assumed | 2.994 | 1494.901 | 0.003 | 0.139 | 0.046 | 0.048 | 0.229 | |||

| Margarine | Equal variances assumed | 3.429 | 0.064 | −3.381 | 2301 | 0.001 | −0.177 | 0.052 | −0.280 | −0.074 |

| Equal variances not assumed | −3.363 | 1413.745 | 0.001 | −0.177 | 0.053 | −0.281 | −0.074 | |||

| Canned pâtés | Equal variances assumed | 1.693 | 0.193 | −4.937 | 2299 | 0.000 | −0.234 | 0.047 | −0.327 | −0.141 |

| Equal variances not assumed | −4.958 | 1448.441 | 0.000 | −0.234 | 0.047 | −0.327 | −0.142 | |||

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pocol, C.B.; Marinescu, V.; Amuza, A.; Cadar, R.-L.; Rodideal, A.A. Sustainable vs. Unsustainable Food Consumption Behaviour: A Study among Students from Romania, Bulgaria and Moldova. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4699. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12114699

Pocol CB, Marinescu V, Amuza A, Cadar R-L, Rodideal AA. Sustainable vs. Unsustainable Food Consumption Behaviour: A Study among Students from Romania, Bulgaria and Moldova. Sustainability. 2020; 12(11):4699. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12114699

Chicago/Turabian StylePocol, Cristina Bianca, Valentina Marinescu, Antonio Amuza, Roxana-Larisa Cadar, and Anda Anca Rodideal. 2020. "Sustainable vs. Unsustainable Food Consumption Behaviour: A Study among Students from Romania, Bulgaria and Moldova" Sustainability 12, no. 11: 4699. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12114699

APA StylePocol, C. B., Marinescu, V., Amuza, A., Cadar, R.-L., & Rodideal, A. A. (2020). Sustainable vs. Unsustainable Food Consumption Behaviour: A Study among Students from Romania, Bulgaria and Moldova. Sustainability, 12(11), 4699. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12114699