An Improved Eclat Algorithm Based on Tissue-Like P System with Active Membranes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Preliminaries

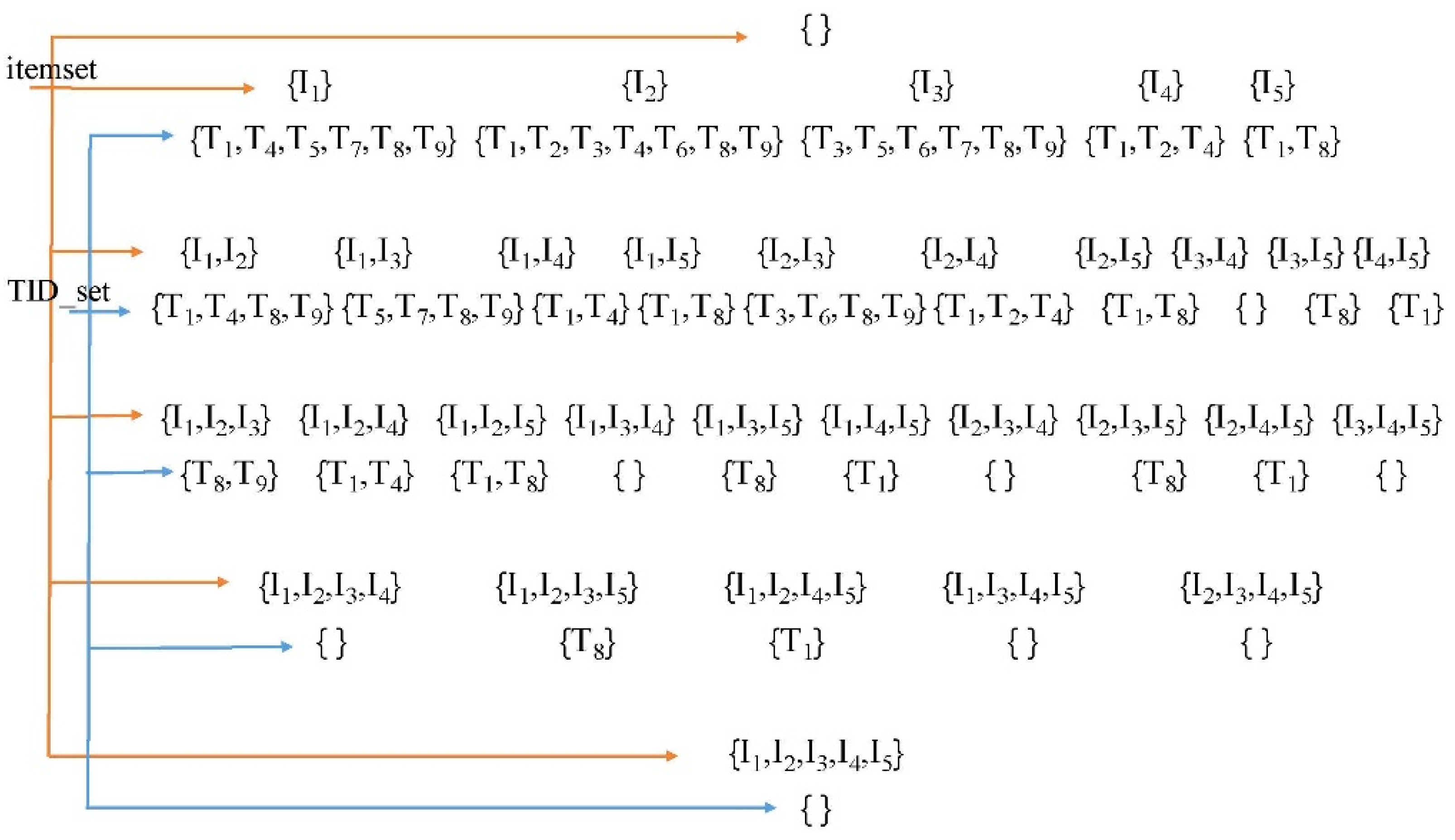

2.1. Frequent Pattern Mining

- (i)

- Pattern: A set of items is called a pattern or an itemset.

- (ii)

- h-pattern: A pattern consisting of items.

- (iii)

- Support count: The number of transactions containing a certain pattern P, denoted as.

- (iv)

- Frequent pattern: A pattern with a support count no less than a given thresholdis called a frequent pattern.

2.2. The Eclat Algorithm

2.3. Tissue-Like P Systems

- (i)

- is a non-empty alphabet that represents a collection of objects in the tissue-like P system.

- (ii)

- syn {1, 2, } * {1, 2, , } represents all channels between cells.

- (iii)

- represents the execution order of the rules in the membranes.

- (iv)

- is the output membrane which stores the final results of the algorithm.

- (v)

- are the cells, each of which is a construct of the form:where is the object set initially in cell , if no object is in cell initially, is empty represented by , and is the set of evolution rules in cell . A rule : means removing the object multiset represented by , generating the object multiset represented by and , and sending the objects in and out to a specific area according to the target command. In the rule, means objects in are sent to the cells connected to the current cell, and v means objects in stay in the current cell. In , is the promoter of the rule. If is in the rule, is the inhibitor of the rule. If the rule has a promoter, the rule can be executed only when all objects in the promoter appear, and if the rule has an inhibitor, the rule cannot be executed when the objects in the inhibitor appear. Active membranes are used to generate subsume indices for frequent 1-patterns, and dissolved when all subsume indices are found.

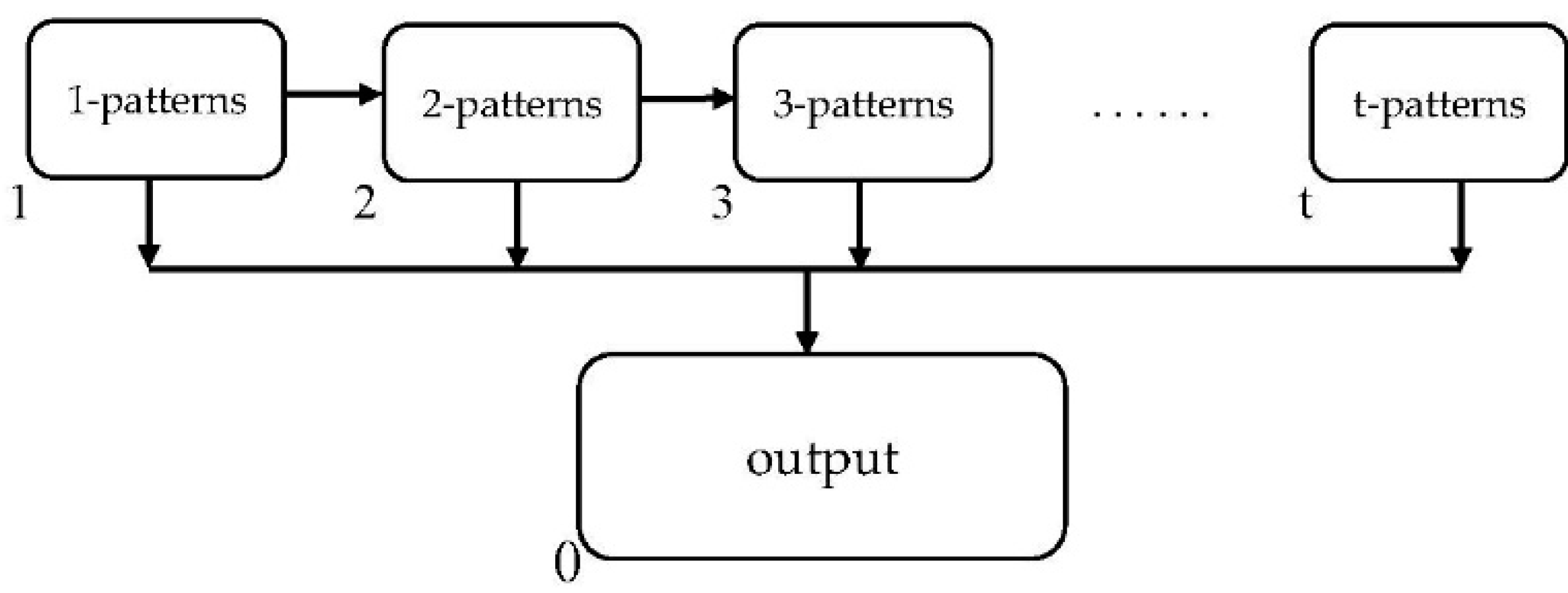

3. The ETPAM Algorithm

3.1. Improvements to the Eclat Algorithm

3.2. Algorithm and Evolution Rules

- (i)

- O = {, ,,, , ,,, , , }, for 1 1 ;

- (ii)

- syn = {{0,1}, {0,2},,{0,}; {1,2}, {2,3}{−1,}};

- (iii)

- = {};

- (iv)

- = (, ), = (, ) = (, );

- (v)

- = 0.

3.3. Computing Process

3.4. Algorithm Specification

| Algorithm 1. ETPAM. |

| Input: Transactional database; representing the threshold k; |

| Method: |

| { |

| Rule : Transfer one copy of objects to cell 2. |

| Rule : Generate for 1 j t to check the candidate frequent 1-patterns . |

| Rule : Check all objects in the cell, and one object consumes one . Continue until all objects have been checked or all k copies of have been consumed. Rule : If all k copies of have been consumed, generate an object to add to as a frequent 1-pattern and transfer cell 2, and cell 0. |

| Rule : Generate a new membrane for each frequent 1-pattern , and transfer the corresponding objects and to cell . Rule : In cell , compare objects belonging to and objects belonging to for 1 j’ in parallel, and one consumes one . Finally, if both and remain in the cell, and are not subsume of each other. If just remains, is a subsume of and then is generated. If just remains, is subsume of and then is generated. Continue this way until all subsumes of have been found. Rule : Generate object and transfer it to cell 2 and cell 0 together with all subsumes of . |

| For (2 h t and ) |

| { |

| Rule : Delete objects not belonging to frequent ( − 1)-patterns. |

| Rule : Scan all objects representing the frequent ( − 1)-patterns to generate the objects representing the candidate frequent h-patterns . |

| Rule : Transfer one copy of objects to cell + 1. |

| Rule : Generate for each to check the candidate frequent h-patterns . |

| } |

| Rule : combine frequent patterns in cell 0 with their subsumes to get all frequent patterns of database. |

| } |

| Output: Frequent patterns mined from the database. |

3.5. Time Complexity

4. An Illustrative Example

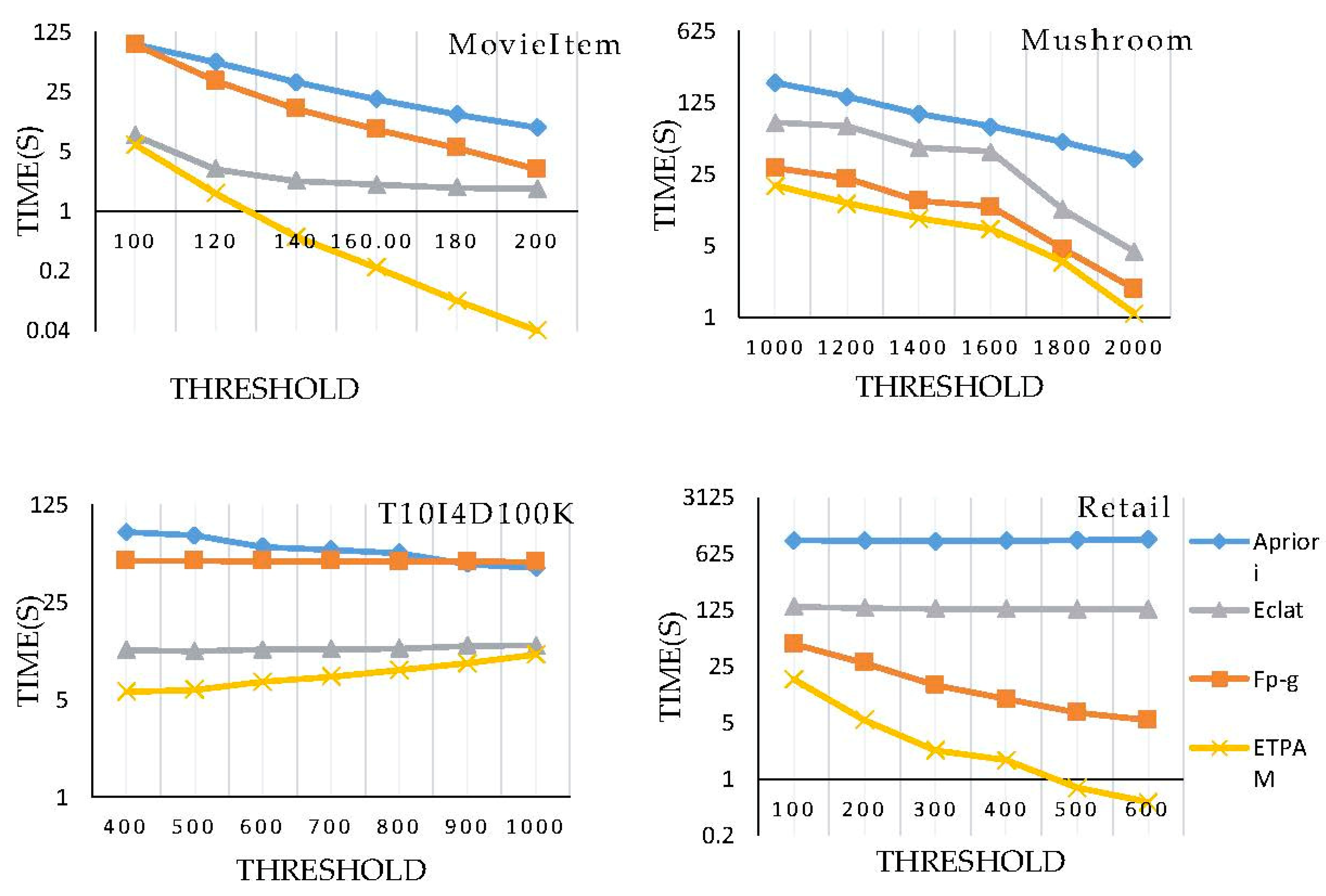

5. Experiments

5.1. Effectiveness of ETPAM in Identifying the Frequent Pattern Itemsets

5.2. Efficiency of the Proposed Algorithm

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Păun, G.; Rozenberg, G.; Salomaa, A. The Oxford Handbook of Membrane Computing; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Păun, G. Computing with membranes. Comput. Syst. Sci. 2000, 61, 108–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Păun, G. Membrane Computing; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, German, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, L.; Păun, G.; Song, B. Flat maximal parallelism in p systems with promoters. Theor. Comput. Sci. 2016, 623, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahya, R.I.; Shamsuddin, S.M.; Yahya, S.I.; Hasan, S.; Alsalibi, B. Automatic 2d image segmentation using tissue-like p system. Int. J. Adv. Soft Comput. Its Appl. 2018, 10, 36–54. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Shi, P.; Peng, H. Membrane computing model for IIR filter design. Inf. Sci. 2016, 329, 164–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhao, Y.; Sun, M. An improved apriori algorithm based on an evolution-communication tissue-like p system with promoters and inhibitors. Discret. Dyn. Nat. Soc. 2017, 2017, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, T.; Vo, B.; Nguyen, L.T.T. A lattice-based approach for mining high utility association rules. Inf. Sci. 2017, 399, 81–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabir, M.M.J.; Xu, S.; Kang, B.H.; Zhao, Z. A new multiple seeds based genetic algorithm for discovering a set of interesting boolean association rules. Expert Syst. Appl. 2017, 74, 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoseini, M.S.; Shahraki, M.N.; Neysiani, B.S. A new algorithm for mining frequent patterns in can tree. In Proceedings of the 2015 2nd International Conference on Knowledge-Based Engineering and Innovation (KBEI), Tehran, Iran, 5–6 November 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Raval, R. F3 algorithm for association rules. Int. J. Comput. Appl. 2017, 164, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Yang, R.; Liu, P. An improved apriori algorithm for association rules of mining. In Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE International Symposium on IT in Medicine & Education, Jinan, China, 14–16 August 2009; Volume 1, pp. 942–946. [Google Scholar]

- Ezhilvathani, A.; Raja, K. Implementation of parallel apriori algorithm on Hadoop cluster. Int. J. Comput. Sci. Mob. Comput. 2013, 2, 513–516. [Google Scholar]

- Ergen, B. Frequent pattern mining under multiple support thresholds. WSEAS Trans. Comput. Res. 2016, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, K.; Liu, H. An improved FP-growth algorithm based on som partition. In Proceedings of the Third International Conference of Pioneering Computer Scientists, Engineers and Educators, ICPCSEE 2017, Changsha, China, 22–24 September 2017; pp. 166–178. [Google Scholar]

- Suvalka, B.; Khandelwal, S.; Patel, C. Revised ECLAT Algorithm for Frequent Itemset Mining. In Information Systems Design and Intelligent Applications; Springer: New Delhi, India, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Z.; Yang, J.; Zhang, T.; Liu, F. An improved eclat algorithm for mining association rules based on increased search strategy. Int. J. Database Theory Appl. 2016, 9, 251–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jusoh, J.A.; Man, M. Modifying iEclat Algorithm for Infrequent Patterns Mining. Adv. Sci. Lett. 2018, 24, 1876–1880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vo, B.; Le, T.; Coenen, F.; Hong, T. Mining frequent itemsets using the n-list and subsume concepts. Int. J. Mach. Learn. Cybern. 2016, 7, 253–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Wang, H.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Y. Effective algorithms for vertical mining probabilistic frequent patterns in uncertain mobile environments. Int. J. Ad Hoc Ubiquitous Comput. 2016, 23, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, B.; Zhang, C.; Pan, L. Tissue-like p systems with evolutional symport/antiport rules. Inf. Sci. 2017, 378, 177–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, B.; Pan, L. The computational power of tissue-like p systems with promoters. Theor. Comput. Sci. 2016, 641, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dam, T.L.; Li, K.; Fournier-Viger, P.; Duong, Q. An efficient algorithm for mining top-rank-k frequent patterns. Appl. Intell. 2016, 45, 96–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Pei, J.; Yin, Y. Mining frequent patterns without candidate generation. In Proceedings of the 2000 ACM SIGMOD International Conference on Management of Data, Dallas, TX, USA, 15–18 May 2000; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Zaki, M.J. Scalable algorithms for association mining. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2000, 12, 372–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, L.; Păun, G.; Zhang, G. Spiking neural p systems with communication on request. Int. J. Neural Syst. 2017, 27, 1750042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Item | TID_Set |

|---|---|

| I1 | T1 T4 T5 T7 T8 T9 |

| I2 | T1 T2 T3 T4 T6 T8 T9 |

| I3 | T3 T5 T6 T7 T8 T9 |

| I4 | T1 T2 T4 |

| I5 | T1 T8 |

| Algorithm | Time Complexity |

|---|---|

| Apriori [7] | O(|| + t| − 1| | − 1|) |

| Parallel Apriori algorithm on | |

| Hadoop Cluster [13] | O(|| + t| − 1| | − 1|) |

| FP-growth [24] | O() |

| Eclat [25] | O(t(t + 1)) |

| dEclat [15] | O(t(t + 1)) |

| ETPAM | O(t) |

| Cell 0 | Cell 1 | |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | {}, {}, {}, {} {} | |

| 1 | {}, {}, {}, {}, {}, , () | |

| 2 | {} {} {} () | |

| 3 | {} {} {} () |

| Cell 0 | Cell 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| 3 | {} {} {}{} | |

| 4 | () | |

| 5 | () | |

| 6 | () | |

| 7 | () |

| Cell 0 | Cell 3 | |

|---|---|---|

| 7 | ||

| 8 | () | |

| 9 | () | |

| 10 | () | |

| 11 | () |

| Database | Transactions | Items | Avg. Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| T10I4D100K | 100,000 | 1000 | 10.0 |

| Mushroom | 8124 | 120 | 23.0 |

| Retail | 88,162 | 16,470 | 10.3 |

| MovieItem | 943 | 80,000 | 84.8 |

| h | Frequent Patterns |

|---|---|

| 1 | {2}{24}{36}{90}{34}{86}{85}{39}{53}{59}{63}{67}{76} |

| 2 | {90, 36}{86, 39}{86, 53}{86, 59}{86, 63}{86, 67}{86, 76}{86, 24}{85, 63}{85, 67}{85, 76}{85, 39}{85, 53} {85, 59}{90, 39}{90, 53}{90, 59}{90, 63}{85, 2}{85, 24}{85, 34}{59, 63}{36, 39}{36, 59}{36, 63}{34, 39} {34, 53}{34, 59}{34, 63}{34, 67}{34, 76}{34, 24}{34, 36}{85, 86}{34, 86}{34, 85}{86, 90}{34, 90}{85, 90} {36, 90}{34, 36}{36, 86}{36, 85}{90, 24} |

| 3 | {34, 36, 85}{90, 36, 39}{90, 36, 59}{86, 90, 24}{86, 90, 39}{86, 90, 53}{86, 90, 59}{86, 90, 63}{85, 86, 90} {34, 85, 90}{36, 85, 86}{85, 36, 39}{85, 36, 59}{85, 36, 63}{86, 34, 39}{86, 34, 53}{86, 34, 59}{86, 34, 63} {86, 34, 67}{86, 34, 76}{86, 34, 24}{85, 86, 24}{85, 59, 63}{85, 34, 24}{34, 90, 24}{34, 90, 36}{34, 90, 39} {34, 90, 53}{34, 90, 59}{34, 90, 63}{34, 36, 39}{34, 36, 59}{34, 85, 86}{34, 86, 90}{34, 36, 90}{85, 90, 39} {85, 90, 53}{85, 90, 59}{85, 90, 63}{85, 90, 24}{85, 86, 39}{85, 86, 53}{85, 86, 59}{85, 86, 63}{85, 86, 67} {85, 86, 76}{85, 86, 36}{36, 86, 90}{36, 85, 90}{85, 34, 39}{85, 34, 53}{85, 34, 59}{85, 34, 63}{85, 34, 67} {85, 34, 76}{34, 36, 86}{86, 36, 39}{86, 36, 59} |

| 4 | {85, 86, 90, 39}{85, 86, 90, 53}{85, 86, 90, 59}{85, 86, 90, 63}{85, 90, 36, 59}{85, 86, 36, 39}{85, 86, 36, 59} {85, 86, 34, 39}{85, 86, 34, 53}{85, 86, 34, 59}{85, 86, 34, 63}{85, 86, 34, 67}{85, 86, 34, 76}{85, 86, 34, 24} {36, 85, 86, 90}{36, 34, 86, 85}{85, 34, 36, 39}{85, 34, 36, 59}{90, 86, 34, 85}{36, 90, 34, 86}{34, 36, 85, 90} {85, 34, 90, 24}{85, 34, 90, 36}{85, 34, 90, 39}{85, 34, 90, 53}{85, 34, 90, 59}{85, 34, 90, 63}{86, 34, 90, 24} {86, 34, 90, 39}{86, 34, 90, 53}{86, 34, 90, 59}{86, 34, 90, 63}{86, 34, 36, 39}{86, 34, 36, 59}{85, 90, 36, 39} {85, 86, 90, 24} |

| 5 | {85, 86, 34, 90, 59}{85, 86, 34, 90, 63}{85, 86, 34, 90, 53}{85, 86, 34, 90, 24}{85, 86, 34, 36, 39}{85, 86, 34, 36, 59}{85, 86, 34, 90, 39} |

| 6 |

| h | Frequent Patterns |

|---|---|

| 1 | {124}{106}{34}{86}{85}{88}{19}{37}{55}{75}{109}{91}{127} |

| 2 | {109, 91}{37, 91}{109, 55}{55, 75}{106, 37}{106, 55}{106, 75}{106, 127}{106, 91}{106, 109}{19, 88} {37, 88}{55, 88}{75, 88}{19, 37, 75}{127, 19, 37}{124, 75}{109, 124}{124, 91}{124, 127}{106, 19} {127, 88}{109, 88}{88, 91}{19, 37}{19, 55}{19, 75}{127, 19}{109, 19}{19, 91}{37, 55}{37, 75}{127, 37} {109, 37}{127, 55}{55, 91}{127, 75}{109, 75}{75, 91}{109, 127}{127, 91} |

| 3 | {106, 55, 91}{106, 109, 55}{19, 37, 91}{19, 55, 75}{127, 19, 55}{109, 19, 75}{19, 75, 91}{106, 127, 75} {106, 75, 91}{106, 109, 75}{109, 127, 88}{127, 88, 91}{109, 88, 91}{109, 55, 75}{106, 127, 91} {106, 109, 127}{106, 109, 91}{127, 75, 88}{109, 75, 88}{75, 88, 91}{109, 19, 37}{55, 75, 91} {109, 127, 55}{127, 19, 88}{109, 19, 88}{19, 88, 91}{127, 37, 88}{109, 37, 88}{37, 88, 91}{127, 55, 88} {109, 55, 88}{55, 88, 91}{109, 124, 75}{124, 75, 91}{124, 127, 75}{109, 19, 91}{37, 55, 75}{109, 37, 91} {127, 37, 55}{109, 37, 55}{37, 55, 91}{127, 37, 91}{127, 55, 75}{127, 37, 75}{37, 75, 91}{109, 127, 37} {127, 55, 91}{109, 55, 91}{127, 75, 91}{109, 127, 91}{109, 127, 75}{109, 75, 91}{109, 124, 91} {109, 124, 127}{124, 127, 91}{109, 37, 75}{106, 127, 19}{106, 19, 91}{106, 127, 55}{109, 127, 19} {127, 19, 91}{106, 109, 19}{106, 127, 37}{106, 37, 91}{109, 19, 55}{19, 55, 91}{127, 19, 75}{106, 109, 37} |

| 4 | {109, 75, 88, 91}{109, 127, 88, 91}{109, 127, 19, 37}{127, 19, 37, 91}{109, 19, 37, 91}{109, 127, 19, 55} {127, 19, 55, 91}{109, 19, 55, 91}{109, 127, 19, 75}{127, 19, 75, 91}{109, 19, 75, 91}{109, 127, 19, 91} {109, 127, 37, 55}{127, 37, 55, 91}{109, 37, 55, 91}{109, 127, 37, 75}{127, 37, 75, 91}{109, 37, 75, 91} {109, 127, 37, 91}{109, 127, 55, 75}{127, 55, 75, 91}{109, 55, 75, 91}{109, 127, 55, 91}{109, 127, 75, 91} {109, 124, 75, 91}{109, 124, 127, 75}{124, 127, 75, 91}{109, 124, 127, 91}{106, 109, 127, 19} {106, 109, 19, 91}{106, 109, 127, 37}{106, 109, 37, 91}{106, 109, 127, 55}{106, 109, 55, 91} {106, 127, 75, 91}{106, 109, 127, 75}{106, 109, 75, 91}{106, 109, 127, 91}{109, 127, 19, 88} {127, 19, 88, 91}{109, 19, 88, 91}{109, 127, 37, 88}{127, 37, 88, 91}{109, 37, 88, 91}{109, 127, 55, 88} {127, 55, 88, 91}{109, 55, 88, 91}{109, 127, 75, 88}{127, 75, 88, 91} |

| 5 | {109, 127, 37, 55, 91}{109, 127, 37, 75, 91}{109, 127, 19, 37, 91}{109, 127, 55, 75, 91}{109, 124, 127, 75, 91}{106, 109, 127, 75, 91}{109, 127, 19, 88, 91}{109, 127, 37, 88, 91}{109, 127, 55, 88, 91}{109, 127, 75, 88, 91}{109, 127, 19, 55, 91}{109, 127, 19, 75, 91} |

| 6 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jia, L.; Xiang, L.; Liu, X. An Improved Eclat Algorithm Based on Tissue-Like P System with Active Membranes. Processes 2019, 7, 555. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr7090555

Jia L, Xiang L, Liu X. An Improved Eclat Algorithm Based on Tissue-Like P System with Active Membranes. Processes. 2019; 7(9):555. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr7090555

Chicago/Turabian StyleJia, Linlin, Laisheng Xiang, and Xiyu Liu. 2019. "An Improved Eclat Algorithm Based on Tissue-Like P System with Active Membranes" Processes 7, no. 9: 555. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr7090555

APA StyleJia, L., Xiang, L., & Liu, X. (2019). An Improved Eclat Algorithm Based on Tissue-Like P System with Active Membranes. Processes, 7(9), 555. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr7090555