Does Identification Influence Continuous E-Commerce Consumption? The Mediating Role of Intrinsic Motivations

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

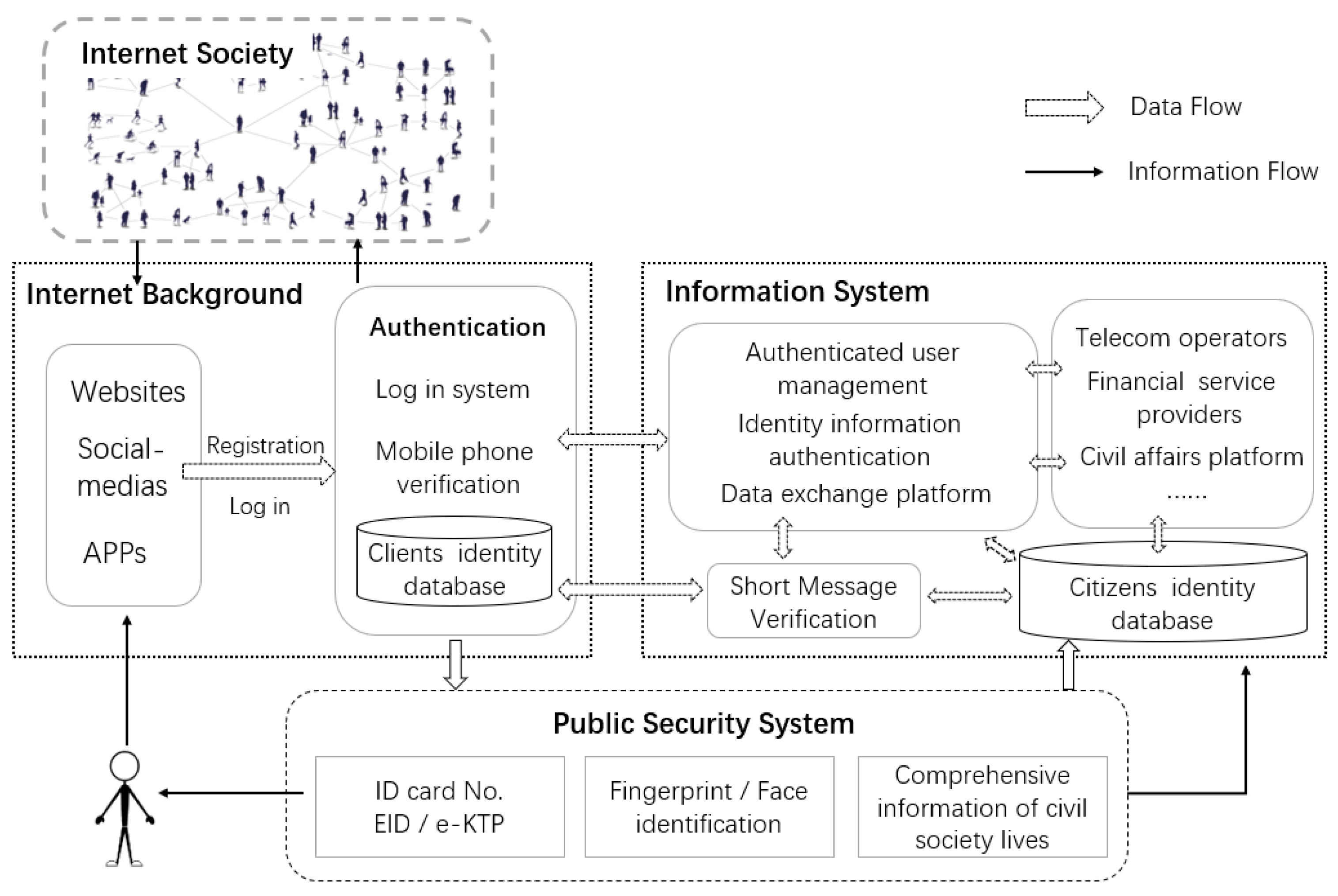

2.1. Identification and Anonymity on the Internet

2.2. Motivation and Self-Determination Theory

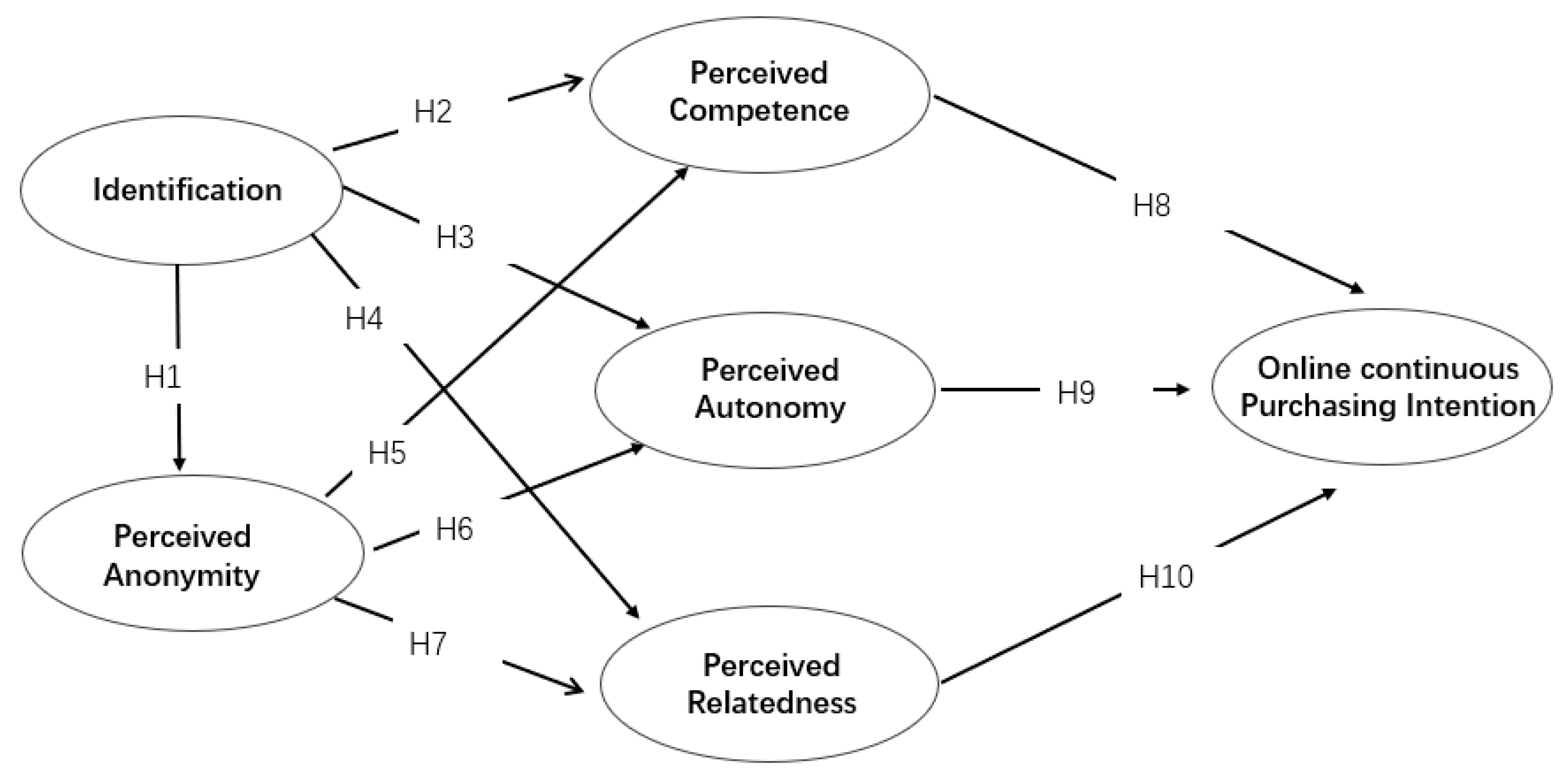

3. Research Model and Hypotheses

3.1. Identification

3.2. Anonymity Perception

3.3. Online Continuous Purchasing Intention

3.4. Self-Determination Factors

4. Methodology

4.1. Data Collection

4.2. Measures

5. Data Analysis and Results

5.1. Reliability and Validity of the Measurement Items

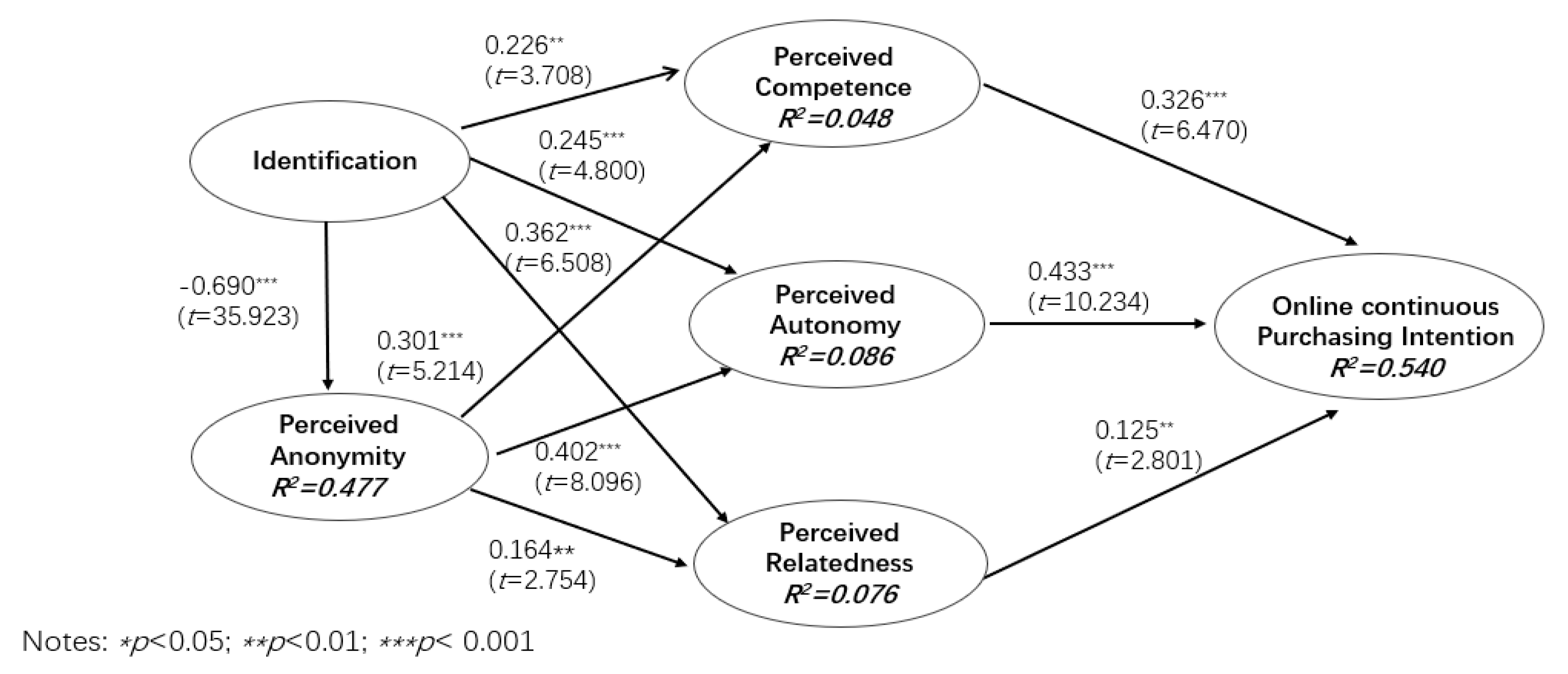

5.2. Structural Model

5.3. Mediating Effect Test of Self-Determination

6. Discussion and Conclusions

6.1. Discussion

6.2. Theoretical Implications

6.3. Practical Implications

6.4. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Huang, Z.; Benyoucef, M. From e-commerce to social commerce: A close look at design features. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2013, 12, 246–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, C.; Lee, Z.W.; Chan, T.K. Self-disclosure in social networking sites: The role of perceived cost, perceived benefits and social influence. Internet Res. 2015, 25, 279–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W. Requirement management for product-service systems: Status review and future trends. Comput. Ind. 2017, 85, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lien, C.H.; Cao, Y. Examining WeChat users’ motivations, trust, attitudes, and positive word-of-mouth: Evidence from China. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 41, 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dan, C. Consumer-To-Consumer (C2C) Electronic Commerce: The Recent Picture. Int. J. Netw. Commun. 2014, 4, 29–32. [Google Scholar]

- Chaparro-Peláez, J.; Agudo-Peregrina, Á.F.; Pascual-Miguel, F.J. Conjoint analysis of drivers and inhibitors of e-commerce adoption. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 1277–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Li, Y. Usability evaluation of e-commerce on B2C websites in China. Procedia Eng. 2011, 15, 5299–5304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molla, A.; Licker, P.S. E-commerce systems success: An attempt to extend and respecify the Delone and MacLean model of IS success. J. Electron. Commer. Res. 2001, 2, 131–141. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, C.; Palvia, P.; Lin, H.N. The roles of habit and web site quality in e-commerce. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2006, 26, 469–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfinbarger, M.; Gilly, M.C. eTailQ: Dimensionalizing, measuring and predicting etail quality. J. Retail. 2003, 79, 183–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katerattanakul, P. Framework of effective web site design for business-to-consumer Internet commerce. INFOR Inf. Syst. Oper. Res. 2002, 40, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behavior; Plenum: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Basu, A.; Muylle, S. Authentication in e-commerce. Commun. ACM 2003, 46, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marx, G.T. What’s in a Name? Some Reflections on the Sociology of Anonymity. Inf. Soc. 1999, 15, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Srivastava, J. Impact of social influence in e-commerce decision making. In Proceedings of the Ninth International Conference on Electronic Commerce, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 19–22 August 2007; pp. 293–302. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, T.P.; Ho, Y.T.; Li, Y.W.; Turban, E. What drives social commerce: The role of social support and relationship quality. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2011, 16, 69–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X. Internet Anonymous Space: Emerging Order and Governance Logic. Chong Qing Soc. Sci. 2018, 8, 26–34. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Scott, S.V.; Orlikowski, W.J. Entanglements in Practice: Performing Anonymity Through Social Media. MIS Q. 2014, 38, 873–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subrahmanyam, K.; Reich, S.M.; Waechter, N.; Espinoza, G. Online and offline social networks: Use of social networking sites by emerging adults. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2008, 29, 420–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joinson, A.N. Oxford Handbook of Internet Psychology; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hite, D.M.; Voelker, T.; Robertson, A. Measuring perceived anonymity: The development of a context independent instrument. J. Methods Meas. Soc. Sci. 2014, 5, 22–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, H. Beyond anonymity, or future directions for Internet identity research. New Media Soc. 2006, 8, 859–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, R. Social Identity; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Luarn, P.; Hsieh, A.Y. Speech or silence: The effect of user anonymity and member familiarity on the willingness to express opinions in virtual communities. Online Inf. Rev. 2014, 38, 881–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christopherson, K.M. The positive and negative implications of anonymity in Internet social interactions: “On the Internet, Nobody Knows You’re a Dog”. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2007, 23, 3038–3056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turkle, S. Life on the Screen: Identity in the Age of the Internet; Weidenfeld and Nicolson: London, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, S. Who Needs Identity? In Questions of Cultural Identity; Hall, S., du Gay, P., Eds.; Sage: London, UK, 1996; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Li, G.; Hu, Y.; Li, Y. How Anonymity Influence Self-Disclosure Tendency on Sina Weibo: An Empirical Study. Anthropologist 2016, 26, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baym, N.K. The Emergence of On-line Community. In Cybersociety 2.0: Revisiting Computer-Mediated Communication and Community; Jones, S.G., Ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1998; pp. 35–68. [Google Scholar]

- McLeod, P.L. A comprehensive model of anonymity in computer-supported group decision making. In Proceedings of the Eighteenth International Conference on Information Systems, Atlanta, GE, USA, 14–17 December 1997; pp. 223–234. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, C.; Rolland, E. Knowledge-sharing in virtual communities: Familiarity, anonymity and self-determination theory. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2012, 31, 1133–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultheiss, O.C.; Strasser, A.; Rösch, A.G.; Kordik, A.; Graham, S.C.C. Motivation. Encycl. Hum. Behav. 2012, 498, 650–656. [Google Scholar]

- Deci, E.L. Intrinsic Motivation; Plenum: New York, NY, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Yoo, C.W.; Sanders, G.L.; Moon, J. Exploring the effect of e-WOM participation on e-Loyalty in e-commerce. Decis. Support Syst. 2013, 55, 669–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.L.; Lu, H.P. Consumer behavior in online game communities: A motivational factor perspective. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2007, 23, 1642–1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.; Tai, Z.; Tsai, K.C. Perceived ease of use in prior e-commerce experiences: A hierarchical model for its motivational antecedents. Psychol. Mark. 2010, 27, 874–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillard, A. Self-determination theory. Int. Encycl. Soc. Behav. Sci. 2013, 91, 486–491. [Google Scholar]

- Jian, D.; Duan, J.; Wang, X. New development of motivation theory: Self-determination theory. Adv. Psychol. 2011, 1, 46–49. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, R.M.; Kuhl, J.; Deci, E.L. Nature and autonomy: An organizational view of social and neurobiological aspects of self-regulation in behavior and development. Dev. Psychopathol. 1997, 9, 701–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deci, E.L.; Connell, J.P.; Ryan, R.M. Self-determination in a work organization. J. Appl. Psychol. 1989, 74, 580–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Lu, Y.; Wang, B.; Chau, P.Y.; Zhang, L. Cultivating the sense of belonging and motivating user participation in virtual communities: A social capital perspective. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2012, 32, 574–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- deCharms, R. Personal Causation; Academic: New York, NY, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. Play and intrinsic rewards. In Flow and the Foundations of Positive Psychology; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 135–153. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, R.M. Control and information in the intrapersonal sphere: An extension of cognitive evaluation theory. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1982, 43, 450–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowlby, J. The Making and Breaking of Affectional Bonds; Tavistock: London, UK, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister, R.F.; Leary, M.R. The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychol. Bull. 1995, 117, 497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gagné, M.; Deci, E.L. Self-determination theory and work motivation. J. Organ. Behav. 2005, 26, 331–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roca, J.C.; Gagné, M. Understanding e-learning continuance intention in the workplace: A self-determination theory perspective. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2008, 24, 1585–1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.T.; Wang, Y.S.; Liu, E.R. The stickiness intention of group-buying websites: The integration of the commitment–trust theory and e-commerce success model. Inf. Manag. 2016, 53, 625–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, D.; Kim, S.; Acquisti, A. Empirical analysis of online anonymity and user behaviors: The impact of real name policy. In Proceedings of the 2012 45th Hawaii International Conference on System Science (HICSS), Maui, HI, USA, 4–7 January 2012; pp. 3041–3050. [Google Scholar]

- Wagman, J.B.; Miller, D.B. Nested reciprocities: The organism–environment system in perception–action and development. Dev. Psychobiol. J. Int. Soc. Dev. Psychobiol. 2003, 42, 317–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deaux, K. Social identification. In Social Psychology: Handbook of Basic Principles; Higgins, E.T., Kruglanski, A.W., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1996; pp. 777–798. [Google Scholar]

- Sirgy, M.J.; Grewal, D.; Mangleburg, T. Retail environment, self-congruity, and retail patronage: An integrative model and a research agenda. J. Bus. Res. 2004, 49, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, F.; Hogg, M.A. Self-uncertainty, social identity prominence and group identification. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 48, 538–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igbaria, M.; Iivari, J. The effects of self-efficacy on computer usage. Omega 1995, 23, 587–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, C.B.; Sen, S. Consumer-company identification: A framework for understanding consumers’ relationships with companies. J. Mark. 2003, 67, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belén del Río, A.; Vazquez, R.; Iglesias, V. The effects of brand associations on consumer response. J. Consum. Mark. 2001, 18, 410–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedikides, C.; Strube, M.J. The multiply motivated self. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 1995, 21, 1330–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.J.; Ferrin, D.L.; Rao, H.R. Trust and satisfaction, two stepping stones for successful e-commerce relationships: A longitudinal exploration. Inf. Syst. Res. 2009, 20, 237–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rainie, L.; Kiesler, S.; Kang, R.; Madden, M.; Duggan, M.; Brown, S.; Dabbish, L. Anonymity, privacy, and security online. Pew Res. Cent. 2013, 5, 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Brennan, M.; Afroz, S.; Greenstadt, R. Adversarial stylometry: Circumventing authorship recognition to preserve privacy and anonymity. ACM Trans. Inf. Syst. Secur. (TISSEC) 2012, 15, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jessup, L.M.; Connolly, T.; Galegher, J. The effects of anonymity on GDSS group process with an idea-generating task. MIS Q. 1990, 14, 313–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, R.; Brown, S.; Kiesler, S. Why do people seek anonymity on the Internet? informing policy and design. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Paris, France, 27 April–2 May 2013; pp. 2657–2666. [Google Scholar]

- Spears, R. Social Identity Model of Deindividuation Effects. Int. Encycl. Media Eff. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.H.; Chiu, C.M. In justice we trust: Exploring knowledge-sharing continuance intentions in virtual communities of practice. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2010, 26, 235–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlett, C.P.; Gentile, D.A.; Chew, C. Predicting cyberbullying from anonymity. Psychol. Popul. Media Cult. 2016, 5, 171–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.P.; Yu-Jen Su, P. Factors affecting purchase intention on mobile shopping web sites. Internet Res. 2009, 19, 442–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.U.; Kim, W.J.; Park, S.C. Consumer perceptions on web advertisements and motivation factors to purchase in the online shopping. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2010, 26, 1208–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol. Rev. 1977, 84, 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donovan, L.A.; MacIntyre, P.D. Age and sex differences in willingness to communicate, communication apprehension, and self-perceived competence. Commun. Res. Rep. 2004, 21, 420–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.P. Online group buying behavior in CC2B e-commerce: Understanding consumer motivations. J. Internet Commer. 2012, 11, 254–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, B.J. Self-efficacy: An essential motive to learn. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2000, 25, 82–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gefen, D.; Straub, D.W. The relative importance of perceived ease of use in IS adoption: A study of e-commerce adoption. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2000, 1, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stieglitz, S.; Dang-Xuan, L. Emotions and information diffusion in social media—Sentiment of microblogs and sharing behavior. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2013, 29, 217–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Fang, Y.; Wei, K.K.; Ramsey, E.; McCole, P.; Chen, H. Repurchase intention in B2C e-commerce—A relationship quality perspective. Inf. Manag. 2011, 48, 192–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, C.M.; Wang, E.T.; Fang, Y.H.; Huang, H.Y. Understanding customers’ repeat purchase intentions in B2C e-commerce: The roles of utilitarian value, hedonic value and perceived risk. Inf. Syst. J. 2014, 24, 85–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, Y. Understanding the role of sense of presence and perceived autonomy in users’ continued use of social virtual worlds. J. Comput.-Mediat. Commun. 2011, 16, 492–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.S.; Shin, J.K.; Ju, Y. The effect of online social network characteristics on consumer purchasing intention of social deals. Glob. Econ. Rev. 2014, 43, 25–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrebi, S.; Jallais, J. Explain the intention to use smartphones for mobile shopping. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2015, 22, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, C.; Palvia, P.; Lin, H.N. Stage antecedents of consumer online buying behavior. Electron. Mark. 2010, 20, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiau, W.L.; Luo, M.M. Factors affecting online group buying intention and satisfaction: A social exchange theory perspective. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2012, 28, 2431–2444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charbonneau, D.; Barling, J.; Kelloway, E.K. Transformational leadership and sports performance: The mediating role of intrinsic motivation. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 31, 1521–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabhu, V.; Sutton, C.; Sauser, W. Creativity and certain personality traits: Understanding the mediating effect of intrinsic motivation. Creat. Res. J. 2008, 20, 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapata-Phelan, C.P.; Colquitt, J.A.; Scott, B.A.; Livingston, B. Procedural justice, interactional justice, and task performance: The mediating role of intrinsic motivation. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2009, 108, 93–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernet, C.; Austin, S.; Trépanier, S.G.; Dussault, M. How do job characteristics contribute to burnout? Exploring the distinct mediating roles of perceived autonomy, competence, and relatedness. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2013, 22, 123–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.C.; Jang, S.J. Motivation in online learning: Testing a model of self-determination theory. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2010, 26, 741–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrabian, A.; Russell, J.A. An Approach to Environmental Psychology; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Jacoby, J. Stimulus-organism-response reconsidered: An evolutionary step in modeling (consumer) behavior. J. Consum. Psychol. 2002, 12, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Lennon, S.J. Effects of reputation and website quality on online consumers’ emotion, perceived risk and purchase intention: Based on the stimulus-organism-response model. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2013, 7, 33–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, V.A. Stimuli–organism-response framework: A meta-analytic review in the store environment. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 1420–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohaib, O.; Kang, K.; Nurunnabi, M. Gender-Based iTrust in E-Commerce: The Moderating Role of Cognitive Innovativeness. Sustainability 2019, 11, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canary, D.J.; Spitzberg, B.H. A model of the perceived competence of conflict strategies. Hum. Commun. Res. 1989, 15, 630–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, S.; Wiedenbeck, S. The mediating effects of intrinsic motivation, ease of use and usefulness perceptions on performance in first-time and subsequent computer users. Interact. Comput. 2001, 13, 549–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong-bo, G.; Yin, J.Z. The strategy comparison of Sino-US B2C e-commerce company. In Proceedings of the 2012 International Conference on Management Science and Engineering (ICMSE), Dallas, TX, USA, 22–22 September 2012; pp. 148–152. [Google Scholar]

- Anwar, S.T. Alibaba: Entrepreneurial growth and global expansion in B2B/B2C markets. J. Int. Entrep. 2017, 15, 366–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringle, C.M.; Wende, S.; Becker, J.M. SmartPLS 3. Hamburg: SmartPLS. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2014, 9, 419–445. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J.; Dijkstra, T.K.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Diamantopoulos, A.; Straub, D.W.; Ketchen, D.J., Jr.; Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Calantone, R.J. Common beliefs and reality about PLS. Organ. Res. Methods 2014, 17, 182–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, F.; Marko, J.S.; Lucas, H.; Volker, G.K. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) An emerging tool in business research. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2014, 26, 106–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, H.W.; Hau, K.-T.; Grayson, D. Goodness of Fit in Structural Equation Models. In Multivariate Applications Book Series. Contemporary psychometrics: A festschrift for Roderick P. McDonald; Maydeu-Olivares, A., McArdle, J.J., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2005; pp. 275–340. [Google Scholar]

- O’brien, R.M. A caution regarding rules of thumb for variance inflation factors. Qual. Quant. 2007, 41, 673–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.W. The partial least squares approach to structural equation modeling. Mod. Methods Bus. Res. 1998, 295, 295–336. [Google Scholar]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behav. Res. Methods Instrum. Comput. 2004, 36, 717–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whetten, D.A. What Constitutes a Theoretical Contribution? Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 490–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, C.; Wang, W. Uses and gratifications of social media: A comparison of microblog and WeChat. J. Syst. Inf. Technol. 2015, 17, 351–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Measure | Value | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | Female | 357 (54.0) |

| Male | 304 (46.0) | |

| Age (years) | 18–25 | 149 (22.5) |

| 26–30 | 171 (25.9) | |

| 31–40 | 269 (40.7) | |

| 41–50 | 63 (9.5) | |

| Older | 9 (1.4) | |

| User history | <2 years | 23 (3.5) |

| 2–3 years | 85 (12.9) | |

| 3–4 years | 110 (16.6) | |

| 4–5 years | 115 (17.4) | |

| >5 years | 328 (49.6) | |

| Frequency of using Taobao | A few times/day | 29 (4.4) |

| A few times/week | 273 (41.3) | |

| A few times/month | 300 (45.4) | |

| A few times/year | 59 (8.9) |

| Items | Loading | t-Value | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ID: Identification (Cronbach’ α = 0.789; CR = 0.861; AVE = 0.609) [28] | ||||

| ID1: I use my real name or screen name on Taobao.com | —— | —— | —— | —— |

| ID2: I post content about my true identity from my Taobao account | 0.740 | 28.805 | 3.157 | 1.187 |

| ID3: My Taobao information contains personal characteristics that enable others to know my true identity | 0.778 | 37.934 | 3.190 | 1.114 |

| ID4: I left clues in Taobao that will allow people to find out my true Identity | 0.777 | 35.266 | 3.321 | 1.182 |

| ID5: People who do not know me can easily find out who I am through my Taobao information | 0.824 | 63.894 | 2.668 | 1.186 |

| PA: Perceived Anonymity (Cronbach’ α = 0.845; CR = 0.889; AVE = 0.618) [21] | ||||

| PA1: I believe that people who can see my Taobao information do not know who I am | 0.691 | 25.164 | 3.590 | 0.968 |

| PA2: I think that people who connect to my Taobao information do not know my real identity | 0.747 | 34.626 | 3.550 | 1.120 |

| PA3: My Taobao information easily tells people who I am * | 0.841 | 62.264 | 3.313 | 1.151 |

| PA4: People who can see my Taobao profile know my real identity * | 0.826 | 55.512 | 3.527 | 1.06 |

| PA5: My real personal identity can be guessed or known by people who can see my Taobao information * | 0.816 | 56.982 | 3.250 | 1.121 |

| PC: Perceived Competence (Cronbach’ α = 0.668; CR = 0.818; AVE = 0.601) [31,40] | ||||

| PC1: I am capable of using Taobao well | 0.817 | 43.358 | 4.228 | 0.744 |

| PC2: Buying in Taobao gives me a sense of accomplishment (dropped) | —— | —— | —— | —— |

| PC3: Purchasing the products using Taobao makes me feel that I am a capable person | 0.804 | 34.868 | 4.374 | 0.753 |

| PC4: I often feel that I am competent when shopping on Taobao | 0.700 | 20.034 | 3.956 | 0.842 |

| PO: PerceivedAutonomy (Cronbach’ α = 0.659; CR = 0.813; AVE = 0.592) [31,40] | ||||

| PO1: I feel that I can buy products freely on Taobao | 0.800 | 42.597 | 4.143 | 0.791 |

| PO2: I feel that I am more of myself on Taobao (dropped) | —— | —— | —— | —— |

| PO3: I can control over what I want to buy following my own wishes | 0.711 | 22.797 | 4.167 | 0.736 |

| PO4: I can buy whatever I want as I desire on Taobao | 0.794 | 45.769 | 4.316 | 0.810 |

| PR: Perceived Relatedness (Cronbach’ α = 0.744; CR = 0.836; AVE = 0.560) [31,40] | ||||

| PR1: I really like the sellers on Taobao | 0.795 | 32.142 | 3.583 | 0.776 |

| PR2: The sellers on Taobao care about me. | 0.735 | 28.015 | 3.580 | 0.954 |

| PR3: The sellers on Taobao are friendly towards me | 0.708 | 19.642 | 3.432 | 0.930 |

| PR4: I feel a lot of closeness and intimacy on Taobao | 0.752 | 22.725 | 3.414 | 0.981 |

| PI: Online continuous purchasing intention (Cronbach’ α = 0.758; CR = 0.848; AVE = 0.585) [92] | ||||

| PI1: I intend to use Taobao to shop in the next 12 months | 0.864 | 68.166 | 4.178 | 0.859 |

| PI2: I would continue to use Taobao in the next 12 months | 0.721 | 27.969 | 4.184 | 0.854 |

| PI3: I plan to shop on Taobao in the next 12 months | 0.641 | 18.795 | 4.256 | 0.782 |

| PI4: I expect to shop on Taobao in the next 12 months | 0.813 | 41.000 | 4.146 | 0.914 |

| X | ID | PA | PC | PO | PR | PI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identification (ID) | (0.780) | |||||

| Perceived Anonymity (PA) | −0.690 | (0.786) | ||||

| Perceived Competence (PC) | 0.018 | 0.145 | (0.775) | |||

| Perceived Autonomy (PO) | 0.153 | 0.233 | 0.528 | (0.770) | ||

| Perceived Relatedness (PR) | 0.248 | −0.085 | 0.306 | 0.186 | (0.748) | |

| Continuous purchasing intention (PI) | 0.080 | 0.212 | 0.609 | 0.651 | 0.307 | (0.765) |

| IV | M | DV | IV > DV | IV > M | IV + M > DV | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IV | M | |||||

| ID | PC | PI | 0.063 * | 0.089 ** | 0.002 | 0.690 *** |

| ID | PO | PI | 0.063 * | 0.095 *** | −0.10 | 0.774 *** |

| ID | PR | PI | 0.063 * | 0.206 *** | 0.012 | 0.206 *** |

| PA | PC | PI | 0.266 *** | 0.08 ** | 0.108 *** | 0.671 *** |

| PA | PO | PI | 0.266 *** | 0.090 *** | 0.095 *** | 0.749 *** |

| PA | PR | PI | 0.266 *** | −0.072 * | 0.182 *** | 0.268 *** |

| Effect Types | Effect Mean | S.E. | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||

| ID→PI (Direct) | −0.0265 | 0.0225 | −0.0707 | 0.0177 |

| ID→PI (Total indirect) | 0.0897 | 0.0228 | 0.0456 | 0.1368 |

| ID→PC→PI | 0.0376 | 0.0118 | 0.0173 | 0.0656 |

| ID→PO→PI | 0.0500 | 0.0132 | 0.0284 | 0.0802 |

| ID→PR→PI | 0.0021 | 0.0087 | −0.0128 | 0.0211 |

| PA→PI (Direct) | 0.0858 | 0.0200 | 0.0427 | 0.1290 |

| PA→PI (Total indirect) | 0.0761 | 0.0235 | 0.0348 | 0.1265 |

| PA→PC→PI | 0.0324 | 0.0119 | 0.0117 | 0.0590 |

| PA→PO→PI | 0.0452 | 0.0134 | 0.0217 | 0.0754 |

| PA→PR→PI | −0.0015 | 0.0032 | −0.0095 | 0.0029 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, X.; Fang, S.; Li, Y.; Wang, H. Does Identification Influence Continuous E-Commerce Consumption? The Mediating Role of Intrinsic Motivations. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1944. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11071944

Chen X, Fang S, Li Y, Wang H. Does Identification Influence Continuous E-Commerce Consumption? The Mediating Role of Intrinsic Motivations. Sustainability. 2019; 11(7):1944. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11071944

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Xi, Shaofen Fang, Yujie Li, and Haibin Wang. 2019. "Does Identification Influence Continuous E-Commerce Consumption? The Mediating Role of Intrinsic Motivations" Sustainability 11, no. 7: 1944. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11071944

APA StyleChen, X., Fang, S., Li, Y., & Wang, H. (2019). Does Identification Influence Continuous E-Commerce Consumption? The Mediating Role of Intrinsic Motivations. Sustainability, 11(7), 1944. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11071944