1. Introduction

The number of international students in the UK has surged by nearly 75% over the past decade [

1], positioning the UK at the forefront of international higher-education-hosting countries worldwide. Universities in urban centres maintain a lion’s share of this young multicultural population. While several studies have long reported difficulties regarding students’ acculturation [

2], digital and social media use have become critical tools for orientation, navigating new spaces, socialisation, and managing change, particularly in global cities such as London [

3,

4].

In this paper, we explore how the concept of the ‘city’ as a space that is simultaneously mediated, affective, and experienced may offer insights not only into how London-based students learn about life and access to a city but also how ‘digital’ place may be learned as a collage of urban ecologies or an assemblage of cultures, media, and socio-technical connections. By exploring the process through which people come to know and understand the digital through the physical city, we suggest that this learning occurs as a dynamic interplay in which both the city and the self are transformed through the cumulative effect of these encounters.

Drawing on the work of urban communication researchers, critical technology scholars [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9], and scholars from critical education studies [

10], this paper investigates the intricate relationship between place, digital expressions, and the formation of social and affective connections within urban environments. Acknowledging the blurred boundaries between physical and virtual spaces, we point to the ways digital technologies foster new forms of sociality, creativity, and connection. We explore how students leverage their aspirations, through digital media and lived experiences, to not only navigate but also learn and construct their understanding of London. In the context of learning about the city, this kind of ‘learning’ involves a combination of virtual and physical modes and activities. We reveal that when the digital is understood as an expansive logic operating across mediated, affective, and experienced geographies, ‘learning’ becomes an assemblage of cultures, media, and sociotechnical elements, and it is never purely physical or digital.

Indeed, research in urban studies has demonstrated that young people are both prolific consumers and producers of media content, with their interactions and experiences both shaping and being shaped by their urban surroundings [

11]. This dynamic relationship reflects the intricate ways in which digital technologies and physical spaces are intertwined, as young people navigate and redefine their environments through the content they create, share, and consume. While Barns [

12], who coined the term “platform urbanism”, implicitly refers to such forms of urban ecologies, our understanding within the context of this study goes further, combining insights into the technological affordances of smartphones with the critical, interpretative learning of users. Smartphones, as ubiquitous, location-aware devices, play a crucial role in mediating urban experiences, structuring how individuals perceive, interact with, and even transform their surroundings. However, these ecologies are not solely about the technological capacities of devices. They also encompass the complex and often fluid ways in which users construct meanings around place and identity. This critical learning arises from divergent, context-dependent, and locative interpretations of place and self, reflecting a constantly shifting relationship with urban environments. It acknowledges that places are not fixed but instead continuously reshaped by the interactions between the digital and physical worlds, as well as the social, cultural, and political forces that influence them [

13].

Drawing on concepts such as ‘place’ [

14] and creative engagements through place-making [

5,

15], we introduce London as ‘a learnt city’. In doing so, we acknowledge existing research agendas which have uncovered oppositional frames of the ‘learning city’ [

16], which often perpetuate neoliberal frames of the knowledge economy and life-long learning through state-led or managerial interventions (e.g., learning as ‘resource to be mobilised’ with ambiguous empowerment discourses that emphasise personal responsibility), and others that consider socio-cultural perspectives of learning linked with grassroots agendas of agency and rights [

10]. Following this second strand, we recognise ‘learning’ as an active verb and noun that involves concepts of the city as an assemblage [

17,

18] understood as a network of relational entities, such as cultures, media, and socio-technical connections.

The concept of the ‘learnt’ city extends beyond conventional interpretations of being ‘educated’ or ‘cultured’ and is not confined to the structured learning environments of formal institutions, such as universities. Instead, the ‘learnt’ city encompasses the diverse and layered processes through which urban knowledge is gathered, assembled, and collated. These processes span a broad spectrum, from mediated representations and digital–physical experiences to deeply personal and familiar encounters, forming embodied, improvised, and contextually rich understandings of urban spaces. While cities undeniably act as pedagogical entities, shaping our perceptions and interactions (p. 161, [

10]), the notion of the city as a site of ‘learnt attention’ stresses the dynamic and iterative nature of urban learning. It captures the ongoing, often unstructured ways in which individuals engage with and come to ‘know’ the city, underscoring the active, situated, and continuously evolving nature of urban experience.

Deploying a novel empirical methodology that integrates communications infrastructures, asset mapping, and reflective inquiry, we interrogate students’ experiences with and without digital technologies. Social media, mobility, and smartphone apps emerge as particularly crucial for students’ orientation and understanding of the city, encompassing not only physical spaces but also the intricate web of communication, networks, and cultures that shape young people’s daily lives and ultimately regulate their access to the city’s resources.

1.1. Learning the City Beyond Emplacement and Urbanism

The city, as a key analytical category, raises questions about how we manage identity boundaries and spatial constellations. Phenomenological approaches to social geography maintain a close relationship between place and space, ordering the human experience as embodied, habitual, and cognitive [

19]. This power of place to order human intentions, experiences, and actions spatially is reciprocal. In Lefebvre’s words, ‘the concept of space links to the mental and the cultural, the social and the historical’ (p. 209, [

20]); it has the power to reconstitute complex processes that include discovery, production, and creation of landscapes and the city. Space is then real, virtual, or imagined [

21], particularly as identities form through communicative, mediated, and ‘digital passages’ [

22] through local, transitional, and transnational networks [

8,

20,

23].

1.1.1. Space, Cities, and the Digital

Recent studies call for recognising what creative uses of digital media do to emplace agency within space. In 2019, Halegoua tracked the relationship between bodies and urban landscape through the digital, raising essential questions about the ways in which technologies facilitate our assumptions about ‘the everyday’ [

24]. Indeed, everyday experiences assume an ecosystem that hangs in the balance of access and digital literacies, or what some urban communication scholars call the ‘media–architecture complex’ [

22,

25], or what geographers refer to as the ‘communicative sense of space’ [

21,

26].

The production of space is increasingly shaped through informal, networked, and digital avenues, particularly via social media platforms that facilitate the sharing of place-based practices and local narratives. These platforms embody the ‘radical ordinariness’ of everyday spatial experiences, providing new frameworks for interpreting and engaging with the urban environment [

27,

28,

29]. In this context, maps, mobile applications, and other location-based services have emerged as critical tools, reshaping how individuals experience, navigate, and make sense of the city. This integration of digital platforms into the spatial practices of urban life signals a shift toward more personalised, decentralised, and participatory forms of spatial production, challenging traditional conceptions of urban space and its governance.

Platform urbanism, in contrast, highlights the deepening entanglement of urban spaces with digital infrastructures, demonstrating how everyday experiences are increasingly mediated by platforms such as Instagram, Google Maps, Uber, Airbnb, and Deliveroo. As Barns [

12] and Rodgers [

30] argue, these platforms not only structure the spatial practices of city life but also transform them into opportunities for continuous data production, algorithmic coordination, and value extraction. We argue that platform urbanism can expand beyond navigation (e.g., Google Maps and City Mapper) or service-oriented apps (e.g., Deliveroo and Uber) and that social and self-representation platforms (e.g., Instagram, TikTok, and WeChat) expand as they have ‘platformed’ outlets to both mainstream media (e.g., the BBC and

The Guardian), hyperlocal news and information sharing (e.g., locality- or interest-based Facebook groups, WhatsApp groups, etc.), and other public service infrastructures (e.g., the NHS [National Health Service], TfL [Transport for London], etc.) that are increasingly ‘app-fied’ and subject to data extraction. Considering this expanded typology, the approach to platform urbanism reveals how platforms shape the rhythms and flows of contemporary urban life, embedding themselves as critical intermediaries that restructure the spatial, social, cultural, and economic fabric of cities.

This mediation is not merely technical or neutral. It represents a profound shift in the political economy of cities, where platforms actively produce new forms of urban power and control by integrating digital practices into everyday life. They transform cities into sites of pervasive data extraction, where human mobility, consumption, and even social interactions are converted into monetisable data points. As such, platforms act as both infrastructure and economic actors, capturing value from the intersections of digital and physical spaces [

30].

This platformisation of urban life risks amplifying social inequalities; as digital platforms mediate access to critical urban services—like transportation, housing, and labour—they can exacerbate existing spatial and economic divides, privileging certain users, neighbourhoods, and demographics over others [

31]. This digital mediation not only reconfigures the material geographies of the city but also introduces new forms of digital exclusion and surveillance, raising urgent questions about urban justice, privacy, and the rights to the city in an era of pervasive digital intermediation.

1.1.2. Transience in Motion: Encountering the City Through Emplacement

How do digital practices and the ways we use technology to overlay physical spaces influence the ways students learn the city? How do transient experiences of the city feature within these contexts? So-called “emplaced encounters”—the co-presence of bodies in specific, often transient urban spaces—have become central to studies of transnational mobility in global cities. These affective and ephemeral dimensions of place are explored through concepts like “emotional geographies” [

32] and “emplacement platforms” [

8], which facilitate reimagined, localised urban experiences. Yet, as noted earlier, as walking and bodily movement become entwined with appified infrastructures—monitors, trackers, and sensors—they also reveal how urban dwellers are increasingly incorporated into systems of commercialisation and platform governance.

Tracing how international students experience locality and ‘making Melbourne’ through digital connectivity, Martin and Rizvi offer insights about the ‘material issue of media uses in geographical space […whereby] urban mobile populations actively remake culture in their transnational journeys’ (p. 1028, [

29]). This remaking contended with the notion that neither affectivity nor mediated encounters are experiential or representational; veiling and obscuring the real structures underpinning urban life; instead, such structures are a crucial part of the everyday infrastructural materialities of urban experience, revealing anxieties and fears as well as multiple ways for enabling and hindering ‘affective possibilities’ for urban dwellers [

32,

33].

Researchers in place-making acknowledge a drive to create and control how places are understood and learned. This type of learning involves recognising how social actors identify with one another to express their identities and regarding communities’ abilities to organise for building and connecting spaces [

15]. It also includes examining the various ways people utilise digital media to negotiate different expressions and become place-makers, through practices that may reveal pre-existing inequities and exclusions [

34,

35]. Adopting a political perspective on place-making to claim rights to place through digital means [

36,

37] has also illuminated how local urban communities share resources and foster a sense of belonging where symbolic and actual recognition may arise from conflicts surrounding place governance or by enacting tangible and pluralistic place-ness [

38].

1.2. Layering Knowledge Across the Learning City

Research within platform urbanism has invited the ‘encoding’ of technical objects, actions, and humans [

39], as well as non-human actors. Such perspectives often call for different types of urban epistemologies and approaches to knowing or learning about cities [

40], while also addressing ambiguity, doubt, misgivings, and the contradictory values inherent in urban environments [

6,

41]. The question then becomes the extent to which place-making enables residents and transient populations, such as students, to learn about and reflect on those visible and invisible traces, as well as the mediated and embodied experiences, and the layers of experience and emotion.

The concept of the city as an assemblage, drawing notably from the works of scholars such as Amin and Thrift, as well as Colin McFarlane and, indirectly, Shannon Mattern, underscores the dynamic, heterogeneous, and interconnected nature of urban elements and the relationships among them. It has inspired a line of work in recent critical traditions of educational research, focusing on questions of

actually learning in the city [

10]. Advancing critical urbanism [

17], this line of inquiry focuses on the interactions, relations, and networks among diverse elements to argue that complexity and dynamism create constantly evolving configurations of urban life.

Mattern approaches the concept of assemblage from a different angle by examining how media representations, infrastructures, and technologies—ranging from urban screens to data networks—interweave with urban environments. Such an investigation may provide insights into how cities are experienced, understood, perceived, or imagined [

7]. This, we argue, stresses how the cultural dimensions of urban life animate layers that allow researchers to reimagine the technicity of cities in more organic and multifaceted ways, through layers that connect notions of place and the digital with socio-cultural learning.

Recognising the multidimensionality of objects arranged to create a unified whole, the city can be viewed as a collage of urban assemblages that enables students to disassemble its interwoven layers while reflecting on their experiences, which serve as a means for learning about the city and themselves through the city. This perspective provided a framework to analyse insights from our student workshops and focus groups, distilled into three key themes: affected, mediated, and experiential.

Affectivity is intrinsically shaped by the interplay between urban spaces, atmospheres, and activities, profoundly influencing emotional states and consequently altering individuals’ perceptions of the city around them [

42,

43,

44]. Contextual knowledge thus arises not only from individual encounters and collective practices of inhabiting urban environments but also through processes of interaction and acculturation that reflect and amplify the collage of contemporary urban experiences.

Acculturation, in this context, encompasses both cultural maintenance [

45] and active, often ambivalent immersion into the city’s culture, social networks, and infrastructures. Although these dimensions can be fragmented and intertwined, the immersive aspect particularly involves affective engagement and intercultural interactions, fostering novel formations of learning, cultural expression, and belonging. Mike Savage’s concept of elective belonging [

46], which describes the affective and reflexive way individuals choose where and how to belong, often grounded in their narratives of personal identity and life trajectories, offers a rich lens for informing how we approach processes of learning among students. In the context of international students, elective belonging can be used to explore how urban environments are not just navigated physically but inhabited and interpreted emotionally, culturally, and cognitively through processes of learning and attachment. Unlike more stable or inherited notions of belonging (e.g., national, ethnic, or class-based), elective belonging can signal individual agency, temporality, and affect, aligning closely with how international students experience and learn cities—tentatively, selectively, and often through mediated, affective, and experiential layers. Although the original concept is not aligned with media or technology use, its connection to platform dynamics may yield insights not just on where or how students belong, but also on what kinds of belonging are made legible or desirable. This raises the question of whether platforms encourage certain types of elective belonging over others (e.g., consumerist, aesthetic, and diasporic).

These dimensions intersect vividly with mediated experiences, wherein mediation describes how urban inhabitants engage with and interpret their surroundings through digital technologies. These engagements extend to practices of media production, communication, connectivity, and self-representation [

39,

47,

48,

49]. Such mediated activities, deeply embedded in specific locations, simultaneously span geographically dispersed social and cultural networks (cf., [

50]), transforming the city into a collage of urban configurations.

2. Materials and Methods: Layering the City

The aim of this study is to unpack how students learn about, navigate, and make sense of the city—specifically how ‘digital’ urban spaces are experienced as collages of culture, media, socio-technical infrastructures, and everyday encounters. Our research aims to address the following two main questions:

How do London-based students negotiate and make sense of the city through digital media and platforms, cultural representations, and embodied practices?

In what ways do these negotiations foster critical forms of urban learning, and what implications might they hold for pedagogy?

In 2023–2024, a diverse sample of 19 undergraduate and postgraduate students from a London university were recruited. The cohort included 2 British, 4 Indian, 3 French, 1 German, 1 Russian, 2 Taiwanese, 1 Canadian, and 5 Chinese citizens. Students, as a highly mobile and transitional demographic, offer a distinctive lens on how digital technologies mediate adaptation to unfamiliar urban environments. Their experiences highlight the layered and uneven processes of acculturation, orientation, and social connection, shedding light on how place-making unfolds at the intersection of digital media, cultural representation, and embodied spatial practices [

4,

51].

Moreover, students represent a very special social class, defined by both privilege (as belonging to the academic class) and, potentially, but not necessarily, restrained economic circumstances and gender inequality; their urban knowledge is not necessarily conditioned by habitus but by how they choose (or are forced) to approach, learn, and reproduce a city. An expanded notion of elective belonging [

46], as outlined above, offers a reflexive and stratified understanding of belonging that expands our thinking about acculturation, not as assimilation into a fixed culture, but as a layered, selective, and culturally mediated negotiation of identity, place, and social positioning. Similarly to exploring stratification or relationships with local residents, the concept proved helpful in examining how students make sense of urban resources, not just functionally, but also as spaces of potential affiliation, comfort, or alienation.

The sample was recruited through an open call to undergraduate and postgraduate students in Liberal Arts, Informatics, and Digital Culture programmes, reflecting a cohort already predisposed to thinking critically about media, culture, and urban life. While this purposive sample limits generalisability, it provides a rich and situated perspective on how a specific group of international and domestic students negotiate the city through both conceptual and lived frames. Four focus groups were conducted with this entire cohort (approximately 4–6 participants per group), structured to ensure a mix of nationalities and degree levels in each session. This division was not random but instead designed to encourage cross-cultural dialogue while keeping groups small enough for sustained, narrative-rich discussions. From an ethnographic standpoint, the approach prioritises depth over breadth: the methodology aimed to elicit tick descriptions of students’ embodied and mediated encounters with London, co-constructed through playful mapping and dialogue, rather than to produce statistically representative findings.

In this study, collage functions as both a metaphor and an analytic sensibility, capturing the layered, fragmented, and selective ways students assemble knowledge of the city. These layered aspects have informed our methodological approach and underpin the development of a toolkit designed as a learning infrastructure for the city, offering a playful framework for exploring conditions such as learning the city. Drawing on asset mapping (see below), the toolkit operationalises this metaphor, translating collage into a participatory method where students map and narrate their urban experiences through playful and material prompts, highlighting the socio-technical infrastructures through which urban life is mediated. Within this process, asset mapping provides the concrete technique: it anchors the activity in identifying resources, needs, and obstacles, shifting the focus from deficits to potentials. Assembling and mapping resources, knowledge, and connectivity prompts narratives about cultures, infrastructures, and spaces, all of which generate new ways of being in the city [

52]. We argue that this practice of collating, mapping, and narrating can activate meaningful processes of sense-making within place-making and further cultivate means for interrogating the informational, educational, communicative, cultural, and infrastructural elements that comprise cities.

Combining focus groups with asset mapping and co-creation methodologies from fields such as design, geography, and community development, the study created a participatory space where students could collectively narrate, visualise, and reconfigure their experiences of London. Asset mapping approaches that informed the design of the toolkit underscore collaborative processes that foreground the voices and perspectives [

53,

54,

55]. Additionally, the toolkit incorporates perspectives from urban communication and informatics, inviting participants to articulate and share their experiences with communication infrastructures, thereby highlighting the socio-technical systems that shape everyday urban life [

56,

57]. This dimension aimed to uncover the often-overlooked layers of digital and physical connectivity that influence how students navigate, understand, and engage with their cities. Drawing on critical urbanism, which extends the concept of ‘assets’ from material resources to the relational networks of kinship and association, we were able to foreground the dynamic, interdependent nature of urban spaces, recognising the importance of informal networks and community ties in shaping adaptability [

17,

58,

59].

Engaging a ‘logic of inquiry’ [

60], each focus group invited students to narrate and map their urban experiences, expressing how they situate themselves within London. Through this mix of interpretive and collaborative place-making, the

learnt city emerged from their reflections and playful negotiations across digital and physical layers of urban life.

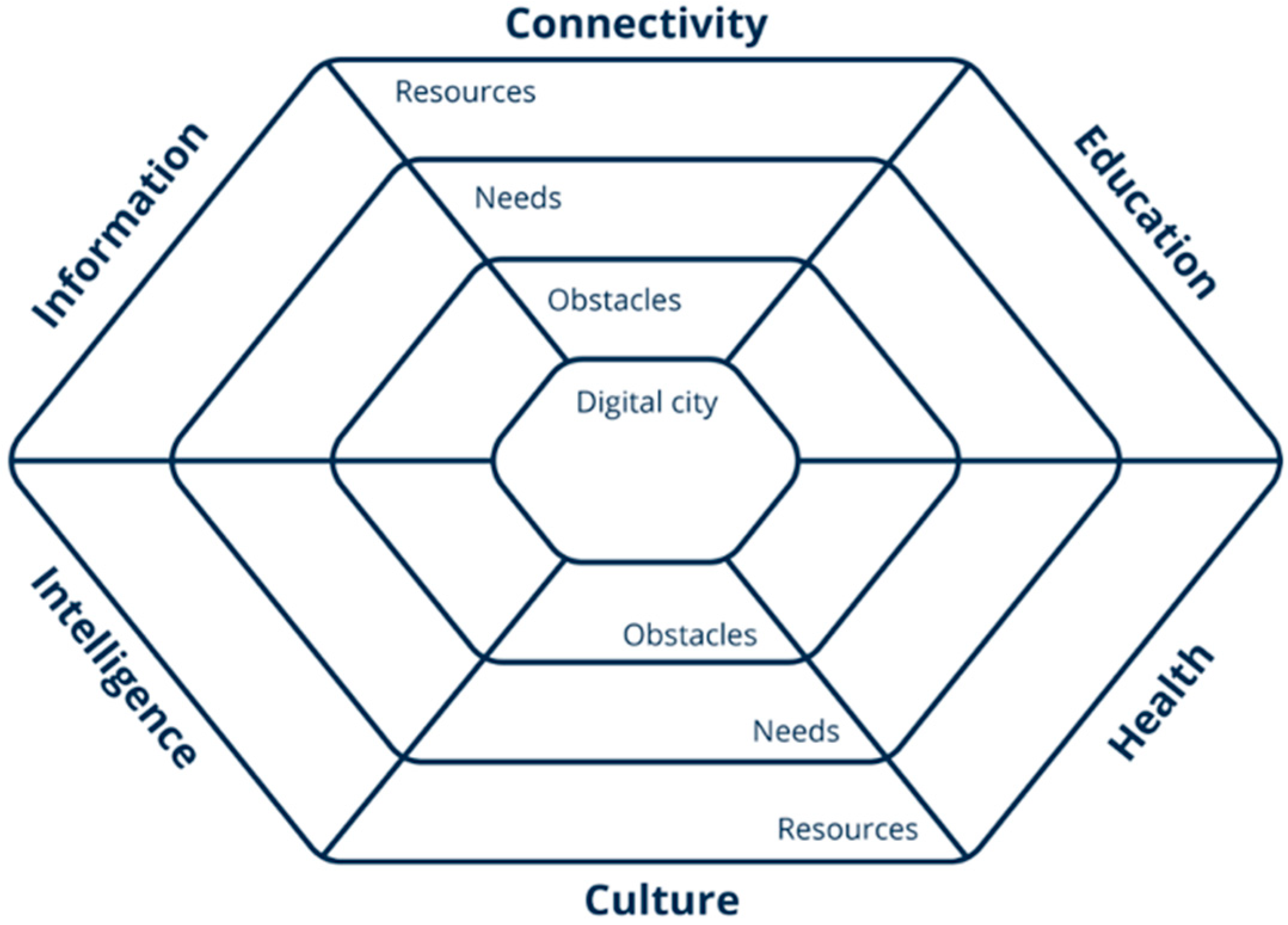

As a starting point, participants were invited to identify ‘hot spots’ (places where information about their life in London is exchanged) and ‘comfort zones’ (places where socialising and bonding take place) on a physical map of Greater London. Using Post-it Notes, participants identified ethnic markets, campus gyms, and cafés as positive spaces that inspire and bring contentment, where social and community interaction takes place. Besides acting as an icebreaker, this activity produced visual data that elicited initial narratives, providing insights into engagements with space and reflections on affective connections among the material, symbolic, and functional dimensions of urban spaces. This offered glimpses into student community life and identity. The next activity of ‘mapping’ involved a board with six themes across 18 vectors, as seen in

Figure 1.

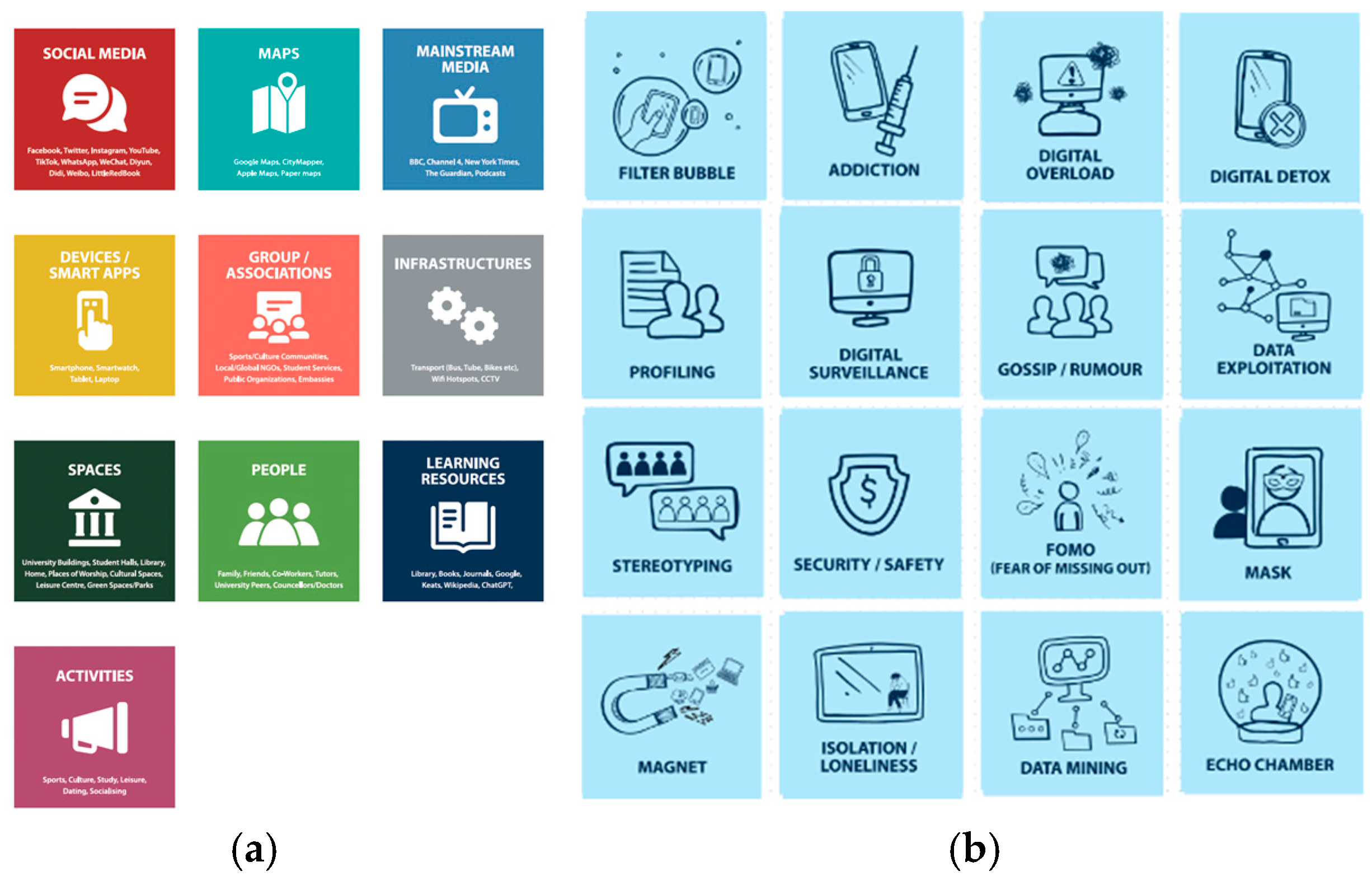

Participants were prompted to place cards from an inventory of ‘assets’ that included both human and non-human material and immaterial resources (

Figure 2), labelling examples of, or types within, the distinct categories; these were to be positioned with the ‘resources’ or ‘needs’ vectors. Several of the asset cards reflected the typology of digital platforms we identified in the previous section, allowing students to identify cross-overs and rethinking of these categories across different fields of activity. For example, while media included several social networking platforms, it also allowed students to reflect on analogue media (e.g., free London newspapers, such as

The Metro, distributed across the London Underground). Similarly, while the TfL (Transport for London) website was identified as a key transport infrastructure, TfL apps were also deemed as a core navigational digital platform embedded with CityMapper. Obstacle cards were designed in relation to popular tensions, social media, and digital infrastructures to prompt perceptions of risk and elicit reflections on experiences of difficulty [see also [

15,

52] for further background and guidance contained in the toolkit]. Post-it Notes were also used to specify various types in both inventories.

Promoting interaction with an inventory of “assets,” the toolkit combines elements of physicalisation and gamification (

Figure 3) with a systems thinking approach [

61,

62] to enable students to reflect upon and visualise their understanding of the ‘digital’ across various layers of experience and as a collage of urban ecologies. This method helped us uncover layers of knowledge, belonging, and sociality, not only to understand students’ sense of city space and city knowledge, but also to reveal how digital platforms may play a role in place-making within these processes. This methodological design generates insights not just into what students know, but how they resist, negotiate, and reconfigure urban infrastructures. We explore this in detail in the next section.

Reflections on Positionality and Limitations

While this study provides rich, situated insights into how international students navigate and understand London’s urban and digital environments, it is important to recognise several limitations. The sample, although diverse in ethnic background, is small and specific to certain institutions. Therefore, the findings cannot be broadly generalised to all student populations but can inform replication across different student demographics and urban settings. Nevertheless, qualitative in its nature, the value of this research lies in the depth and breadth of the narratives students produced, which were facilitated by embodied activities (focus groups and mapping as situated knowledge) and the analytical richness threaded in the results and discussion. As facilitators, our own disciplinary positioning within media and digital culture inevitably shaped the framing of questions and activities, foregrounding critical reflection on platforms and infrastructures as part of students’ urban narratives.

Students represent a distinct social group, marked by transience, varying degrees of privilege, and different modes of access to urban and digital infrastructures. This positionality both enables and constrains the kinds of urban knowledge they produce. We approach this reflexively, acknowledging that their “elective belonging” may differ from longer-term or more marginalised urban residents.

The playful, participatory methodology privileges co-constructed meaning and situated knowledge. This inevitably raises questions about replicability and interpretation. However, we argue that these are strengths rather than weaknesses: the toolkit was designed not to produce fixed knowledge, but to surface layered, contested, and affective engagements with the city, which are valuable for rethinking urban learning as a relational, place-based, and socially diverse process.

3. Results

The city itself, as a key analytical category, prompts questions about how identity boundaries and spatial constellations are managed. To ground our exploration of how London-based students engage with this multifaceted concept, this section offers analytical insights that illuminate the intersection of physical and digital urban experiences. Phenomenological approaches to social geography emphasise the intimate connection between place and space, organising human experience as embodied, habitual, and cognitive. This power of place to spatially order human intentions and experiences is reciprocal; indeed, as Lefebvre articulated, space is not a mere container, but rather it links to the mental, cultural, social, and historical, possessing the power to reconstitute complex processes of discovery and creation within the urban landscape. Building on the idea of cities as affective and mediated assemblages, we explore how digital platforms shape students’ perceptions of urban life, revealing the socio-technical layers that produce and structure communicative senses of space. In doing so, we aim to provide a nuanced understanding of how students encounter, interpret, and construct ‘the learnt city’.

3.1. The Mediated City

The production of space now unfolds through fluid, networked currents, with social media weaving place-based practices and local narratives into shared urban textures. Students arriving in global cities often carry preconceived notions heavily influenced by mediated portrayals, including cinematic and cultural representations. Seeing the city digitally, as our participants contended, is deeply imbricated in several visualisation [

48,

63] ranging from cinematic to social media imagery. These construct a mediated, romanticised vision of the city, with iconic landmarks serving as symbolic signifiers of Western modernity and cultural aspiration. These portrayals have profoundly influenced not only students’ initial expectations but also their subsequent choices regarding residence, social life, and academic pursuits. One student commented:

“I like Covent Garden, Oxford Street, […]. Not only for me but for a lot of international students coming to study abroad, it is a very aspirational thing to do […] Those places remind me, I made it to London, I am finally here. I think that it evokes a happy feeling”.

The dominance of such mediated images in shaping students’ perceptions highlights the power of representation in constructing cultural narratives. The desire to inhabit and experience these iconic spaces reflects how media can shape a kind of ‘aspirational belonging’. Visual social media platforms have amplified the influence of mediated representations. These platforms embody the familiarity of everyday spatial experiences, providing new frameworks for interpreting and engaging with the urban environment. As such, seeing urban spaces through digital devices reconfigures both how cities appear and what may happen there, particularly as using media in place itself constitutes a concrete presence in London. Instagram and TikTok, for example, have become tools for curating and sharing idealised images of urban life. This aligns with the concept of “platform urbanism,” which emphasises the growing interconnection of urban spaces with self-representation and service-oriented platforms, such as Instagram, Google Maps, Uber, Airbnb, and Deliveroo. These platforms not only structure the spatial practices of city life but can also transform them into opportunities for continuous data production, algorithmic coordination, and value extraction. Students often seek out and share “Instagrammable” locations, reinforcing the notion that certain spaces are more desirable or authentic than others. Meanwhile, the desire to ‘emplace’ themselves in virtual spaces is conditioned by negotiating their urban subjectivity, urban temporalities, as well as learning to inhabit the city (cf., [

19]).

Students described gaining a personalised, mediated, and digital awareness of the city. For example, one student noted that Instagram recognised their presence in London and began providing food recommendations. Another found TikTok helpful in discovering new events, such as a themed restaurant experience, that they would not have thought to search for on Google but were drawn to after seeing it on the platform. A third student shared that initially their primary source of information about London came from tagged pictures and stories on Instagram. Still, they observed “a shift towards video content” and found social networking platforms like BeReal offering more recommendations. For others, Instagram operates as a mediating infrastructure where self-presentation, place-making, and algorithmic visibility coalesce, shaping both how individuals navigate cities and how cities themselves are branded and experienced (cf., [

50]).

As a plethora of visual social media interweaves with and influences the spatial practices of the city, newly found networks, forms, contents, and contexts of the mediated city interact with each other to produce new perceptions of the city. A female student confessed that her keen interest in fashion reached a new niche and a new following when she discovered that Instagram’s and TikTok’s Streetfashion tags were popular in London:

“Because in India this kind of fashion is not popular; here it is streetwear fashion […] so I started sharing pictures of me posing in places and I got a massive following, to the point I became a micro-influencer. It’s an interest I developed online, and being here in person”.

As such, the production of new notions of digital London are collated as an urban ecology that depends on learning through not just media reproduction through apps and portable media, but, extending what Elliot and Urry noted in 2010 [

64], the self—in conditions of intensive mobilities—becomes deeply ‘layered’ within technological networks, as well as reshaped by their influence; they condition how the self engages with affect, anxiety, memory, and desire, giving these relations concrete, embodied form. Meanwhile, as students discover, inhabit, and curate Instagrammable spaces and performances, using them as a shorthand for ‘feeling part of London’, they also encourage a sense of consumerist and aesthetic belonging.

In turn, layered place-making unfolds through and is reinforced by diasporic communication networks, where practices of connection, memory, and orientation extend urban belonging across trans-local scales. Chinese students, among our participants, attest to insights shared by others [

25,

65] that platforms like WeChat and Little Red Book enhance their ability to navigate London’s social and cultural nuances following arrival. This echoes Martin and Rizvi’s [

29] findings on how international students actively remake culture in their transnational journeys through digital connectivity. These platforms help them adjust to academic and social environments while maintaining cultural ties and establishing support networks. One student mentioned that collectively, Little Red Book, Weibo, and WeChat have several hundred groups featuring London, with most of them populated by students, in categories like ‘Food’, ‘Culture’, ‘Education’, ‘University Clubs’, ‘Shopping’, ‘amenities’, admin and visa-related information, as well as provincial or regional affiliations. Such spaces are indeed appropriated in different ways to construct locality, producing what Andreas Hepp calls the diasporic heimat (p. 333 [

66]), as we may extend to a sense of elective diasporic belonging, not without tensions, growing as knowledge of the city grows through experience:

“When I was still kind of unfamiliar with the whole city and stuff, so I feel like it’s easier to just go through some content [In Little Red Book] in my mother tongue. But there’s a lot of nonsense too, about perceived dangers and fear mongering about crime and terrorism that is simply not always there… It’s not that hard, but as I lived here for longer, I started to rely more on other networks and local media I came across or what my classmates share.”

Our participants mentioned that the use of local media is organically linked with spatial practices, as it provides information about urban and national events, such as protests, weather, national news, university life, and mobility patterns. Billboards, posters, and reading the Metro or Evening Standard on public transport create a sense of London-ness, animating trans-local subjectivities, particularly as students navigate between the new, the familiar, the affective, and the nostalgic. Mediated representations and expectations shape subjectivities, which have profound implications for students’ initial expectations and subsequent experiences. By inhabiting iconic spaces, students symbolically achieve personal milestones and experiment with new subjectivities, which they can share with their friends in London and abroad.

The allure of these mediated images, however, can lead to a cognitive dissonance between the idealised image of London and the realities of urban life. Students may find themselves grappling with the discrepancy between their preconceived notions and the actual lived experience of the city. Chinese students often mentioned struggling to adjust to the demand of multiple apps to communicate with their new friends and experience the city: “There are a lot of apps that are banned in China, like Snapchat and Instagram. […] we need to download all these to communicate with our new friends [and] adapt to the functions and the norms of the city”.

While, to an extent, our participants reflected that they manage their media environments to maintain a sense of control in their interpersonal relationships, they also deal with multiple social relationships across various social media platforms. They usually refer to the skills they had to develop to manage digital overload, feelings of being overwhelmed and fatigue associated with recommender cultures, and tracking routes to attention economies. Some students even claimed that they “deleted TikTok” with one suggesting that they constantly “got this London content” and were “incapable of sleeping at night” due to it or having severe FOMO (fear of missing out) because they do not experience as much of London as others. Yet, this process of spatial consumption, driven by media-constructed fantasies, also highlights the power of representation in shaping individual experiences and identities.

3.2. The Affective City

Beyond its geographical and cultural significance, London emerges as a pivotal catalyst for personal growth and self-discovery. The affective and ephemeral dimensions of place, explored through concepts like “emotional geographies” and “emplacement platforms”, are central to this experience, where online tools can facilitate reimagined, localised urban encounters. The city’s reputation as a global metropolis, synonymous with independence and autonomy, resonates deeply with students seeking to break free from the constraints of their home environments. For instance, students admitted that “London has been the independence you don’t get in India” and that “London has taught me how to coordinate things with other people.” Other students suggested that “London equals [..] being completely independent”, or that “In London you have more freedom”, and that “you have a lot more autonomy and agency in terms of the options.”

The challenges of navigating a new city, managing finances, and building social connections foster a sense of agency and independence. London becomes more than just a physical location; it serves as a crucible for personal development. The city’s dynamic energy and diverse population provide a fertile ground for students to explore their identities, expand their horizons, and cultivate a sense of self-sufficiency. “Places are familiar, I feel I know the place,” one student noted. “The place where I live is Vauxhall, and I know my accommodation. Places near the campus are very comfortable.” These familiar spaces can serve as a grounding force of acculturation, providing a sense of continuity and stability amidst the chaos and novelty of city life.

However, London can also be a source of anxiety and isolation. Using tracking apps like ‘Find My’ and ‘Life 360’ helps some students manage complexity and navigate the paradox of independence vis-à-vis connection with familial and friend networks. Here, pieces of ‘home’ provide a sense of connection with space/life ‘out there’, while stratifying the ‘out here’ in London. As a few students confessed, using tracking apps with family (‘back home’) and with friends (in London, the UK, or elsewhere) lends weight to the idea of ‘miniaturised mobilities’: functioning in part for managing anxieties associated with mobile lives (p. 1021, [

29]), ref. [

64] while also learning to acknowledge the apps’ sensory power and the balance between connection and surveillance, security and convenience, and independence and comfort. As constant streams of new experiences and challenges can be overwhelming, leading to feelings of nostalgia, the presence of cultural communities and ethnic enclaves offers a sense of connection to one’s homeland.

Students are not just users shaped by platform logics. A recent French MA graduate explained that prior knowledge and expatriate experience in London enabled them to act as a node among newcomers’ social networks, which, however, also operate through word of mouth and physical encounters. Another student, a German BA graduate, reflected on how she produced alternative mappings of arts and crafts spaces and bookshops where she likes to ‘hang out and relax’, some of which are reminiscent of familiar places back home. Just like ‘I deleted TikTok’, students ignored, overrode, or adapted platform suggestions—e.g., “I knew the shortcut,” “I switched off notifications,” “I found a café that wasn’t on Google Maps.” These moments foreground agency in the form of ‘micro-resistances’, everyday tactical improvisations within structures of control. In many cases, resistance is not heroic defiance but mundane negotiation: students testing alternative routes, cultivating “urban sense-making” outside algorithmic defaults.

For students, then, a place not actively sought would become a site of emotional anchoring. An Indian student’s encounter with East London’s Bangladeshi and Pakistani neighbourhoods evoked a powerful, unexpected nostalgia, as if she had been momentarily transported “back home.” She described the comfort she found in the Bengali script, familiar smells, and unexpected cultural proximity, revealing how belonging can emerge through sensory recognition and spatial serendipity, rather than through deliberate identification. This demonstrates diasporic elective belonging through the discovery of symbolically meaningful locations. Yet this elective affinity is laced with discomfort: her sense of home was problematised by the social gaze of her middle-class peers, who view the area and its dwellers with disdain. This dissonance underscores how elective diasporic belonging is always negotiated between the personal resonance of place and the cultural hierarchies that shape its legitimacy. The city’s ability to both challenge and support individuals underscores its role as a crucible for personal growth and transformation. Similarly, to avoid presenting an overly simplistic narrative of ‘happy hybridity’ [

67] that may depoliticise the issues at hand, it is essential also to consider instances where students felt their sense of belonging in the city is disrupted by racial stereotyping and xenophobia.

3.3. The Experiential City

The experiential city encompasses not only a physical space but also an immersive environment where human experiences, sensory perceptions, and social interactions are integral to understanding urban life [

20]. Similarly, experiential learning stems from engaging activities, ranging from learning how to navigate the city to the most mundane, such as shopping in supermarkets and recognising protest spaces. It is a dynamic process fuelled by direct engagement and participation in the city’s everyday life. This kind of learning fosters a deeper understanding of London’s fabric. Walking becomes a crucial aspect of this experiential learning. One participant described how walking in London helped them build a mental map of the city, contrasting it with their car-centric experience in China, and deepening their sense of familiarity and comfort.

This highlights the contrast between a mediated understanding of the city and the embodied knowledge gained through walking. Relatedly, another student observes the contrast between the fast-paced nature of walking in London (“In London there is a thing where you walk with purpose […] people pushing you”) and the more relaxed atmosphere of parks (“But when you go to a park it’s a lot more relaxing. You get to interact with a lot of people, especially people with pets”). These contrasting experiences contribute to a nuanced understanding of the city’s diverse spaces. Encountering different parks through running clubs or as football games evokes affective, kinaesthetic, and collective registers of physical place within urban space [

68], offering opportunities for spontaneous ‘mixing with locals’ and community building beyond pre-existing social or academic circles.

Navigating and engaging with the city’s infrastructure becomes a core part of learning London. Yet, traversing the complexities of urban life often requires a more nuanced understanding of the city. The reliance on digital technologies, such as Google Maps and smartphones, can both facilitate and constrain experiences. While these tools can provide convenience and information, they can also limit opportunities for serendipitous encounters and a deeper engagement with the city’s diverse cultural fabric and learning the city. One student described London as “a coded space”, exclaiming sarcastically: “As in, if I didn’t have my smartphone, I could not function within London….For my first few months in London, yes, OK!… After making a conscious effort to try learning the routes and being less dependent on my smartphone, I managed to make the city less of a coded space.”

Indeed, some students expressed concerns that adhere to critiques of “algorithmic wayfinding” suggesting over-reliance can stifle development of independent spatial competencies or even deskill orientational capacities (e.g., [

26]). Yet, evidence of hybrid competences (learning to “read” the city both digitally and physically) prevails as instances already outlined earlier reveal. Learning to navigate through familiar and routine paths, through serendipity, developing mental maps of favourite places, and switching off to detox in physical spaces like parks, reveals a kind of experiential learning that transforms London from a foreign city into a familiar and dynamic environment.

The juxtaposition of independence and interdependence, of exploration and familiarity, was a common theme, as were experiences of constant surveillance and algorithmic tracking: as one student noted, “the billboards scan the demographic and accordingly show ads to them. Is this like a smart city feature?” Several participants reflected upon their knowledge of being objects of ‘interfacial data collection’ in public spaces (ranging from CCTV cameras to QR Codes, public (yet commercialised) WIFI hotspots, billboards, etc.), expressing tensions between comfort and discomfort, hype over crime and hyper-policing, and exposure and profiling among ‘communities of strangers’ [

49]. For others, attempting to ‘manipulate the algorithms becomes both part of the acculturation journeys, the embodied experiences and hybrid selfhood. One Taiwanese student contends that they use social media algorithms as tools to connect with London-based popular culture and to perform a curated sense of self within the city that strives for both novelty and novel connection with their national identity:

“If you want to integrate a culture, the best way is to get to know its pop culture, so I tried to find certain trends and things I like within London tags. So, I created a new Instagram account and I kind of changed my persona (from original account) and the algorithm stalked me with new content on both accounts…but eventually this is how I found the running clubs and got to know new places and new ways to connect with other Taiwanese students in London and promote our culture here”.

The same student attempted to foreground elective belonging through active signalling of political or cultural identity, especially in diasporic contestations (e.g., Taiwanese vs. Chinese identities): “I always carry something—this little flag… It’s important for me to represent myself like this in this city, and maybe something that shows your identity is important.”

Taken together, these insight reveals an understanding of how platform capabilities can influence urban experiences and a sense of spatial self [often platform-curated] with more active learning environments that encourage reflections based on varied, fluid, emotional, and location-specific interpretations of place. The notion of learnt hybridity presented here goes beyond simply connecting physical and digital realms; it serves as a bridge that redefines the experience and understanding of the city itself through patterns of elective belonging. This self-fashioning through platformed identity and algorithmic curation also highlights how mobility and cultural capital shape contemporary forms of belonging, which blend the adaptive norms of acculturation with a nonlinear process of strategic, identity-driven affiliation. It thus extends the notion of elective belonging [

46] as a mediated, affective, and strategic process, where social media, urban rhythms, and diasporic ties intersect to create new forms of cultural positioning and communal expression.

4. Discussion and Conclusions: Assembling the Layers of the ‘Learnt City’

Our aim in this paper is to offer a fresh perspective on how London-based students develop their understanding of the city, not only through it but also alongside it. Diverging from instrumental notions of the learning city and administrative concepts of the ‘student experience’ [

69], we deployed a qualitative methodology to emphasise agentive subjects, their experiences, and practices.

Students’ narratives suggest that learning about the city is a practice embodied in everyday dwelling, in understanding representations of the city and of the self within it, while uncovering some of the layers of the digital and mediated infrastructures that make up the city. Indeed, the expansion of digital networks and connectivity means that “local” developments can no longer be spatially circumscribed so tightly, and this is underscored through the lens of student experiences. By adopting a notion of emplacement and assemblage as a layered collage of mediated, coded, embodied, and affective learnings of the city, we have enhanced our understanding by focusing not only on digital interactions but also on how technologies are used in specific geographic locations. If digital is understood as an expansive logic operating across national, regional, and urban geographies, our study reveals that learning involves understanding that this logic does not follow uniform patterns or timeframes, or homogeneous outcomes; it is never purely physical or digital. Essentially, transient student populations are constantly reshaping their identities, environments, and the places in which they live.

We also demonstrate that students make sense of urban infrastructures, not just functionally, but as spaces of potential affiliation, comfort, or division. Furthermore, as students forge attachments or disconnections through place-making practices, such as routinised movement or cultural participation, they also create an interplay between mobility and emplacement.

Finally, they forge a sense of learning through expanded patterns of elective belonging [

46], as they appreciate the physical or symbolic features of their new ‘neighbourhoods’, acquiring social capital through university and social networks connecting them to both the ‘here’ and ‘back home’, and asserting new forms of independence, experiencing the city in relation to current imaginaries and aspirations. The student narratives in this study show how the notion of elective belonging is increasingly mediated by platforms and diversified across consumerist, diasporic, aspirational, resistant, and identity-performative registers. For some, Instagram recommendations or Google Maps reviews anchor belonging in consumerist or aesthetic practices as markers of participation in urban life. For others, belonging is affectively diasporic, forged in comfort zones like Chinatown. Aspirational attachments, such as visits to symbolic landmarks, frame London as a site of arrival and aspiration. Yet, students also describe resistant practices—such as switching off, experimenting with alternative routes, or decoding algorithmic mediation—that suggest elective belonging can emerge through the rejection of platform defaults. Finally, elective belonging becomes overtly political or performative when tied to identity signalling, such as diasporic flags or cultural markers displayed in urban space. These accounts illustrate how platforms not only mediate elective belonging but also stratify it, amplifying consumerist and aspirational attachments while still leaving room for resistant and identity-based practices.

Responding to critics’ warnings that over-reliance on apps may stifle more profound engagement with urban space or displace the forms of embodied orientation traditionally associated with urban learning [

26,

70], students themselves often expressed ambivalence toward this possibility. Many expressed concerns about the “cognitive overload” stemming from dependence on digital platforms, more generally, whether for navigation, mobility, services, or through mediated forms of social and cultural exchange. Yet this recognition also opened avenues towards reflection and pathways to developing critical digital literacies. Several students described actively subverting surveillance and cognitive overload by switching off or simply repudiating recommended defaults. Their mundane tactics included testing alternative routes, lingering in spaces overlooked by apps, and cultivating forms of “urban sense-making” that either ignored or knowingly blended algorithmic cues with embodied experience. Such practices are akin to Certeau’s [

71] notion of “tactics”, small acts that reassert user agency within structures of control. In this sense, students are not passive consumers of platform logics but active urban learners who hybridise digital and embodied ways of knowing the city. This hybrid agency suggests that platform dependence may coexist with practices that foster spatial competence, creativity, and alternative mappings of the city. Future longitudinal research could more fully assess how such practices shape, sustain, or limit the development of deeper spatial and digital competences over time.

By highlighting the ways in which this relatively small cohort of students actively engages with multiple, hybrid spaces and cultures of London, we emphasise a city that is learnt as it generates new ways of being in the world. While the three layers of mediated, affective, and experiential narratives that we presented here only offer a glimpse into students’ agentive thinking, we believe that our approach can shed light on further infrastructural or platform-oriented domains of the city. These domains always assemble a manifold of forces and actors, making their materiality (from design logics to history, politics, and planning governance structures) as well as wider media technologies.

Crucially, however, this paper advances a methodological and analytical framework that reimagines urban learning as a collective, situated practice of meaning-making across digital and physical cityscapes. Grounded in critical urbanism, communication theory, and pedagogies of place, it centres adaptation and reflexivity as key modes of engagement. This conceptual reframing holds significant implications. For global cities, it highlights how transient populations, often overlooked in urban policy, actively shape urban knowledge and social imaginaries. For higher education, it suggests the value of recognising the city itself as a pedagogical infrastructure, where informal, affective, and mediated learning contribute to students’ development and social integration. Furthermore, this study’s insights highlight opportunities to design university support structures and curricula that explicitly engage students in critical digital pedagogy, encourage reflection on algorithmic mediation, and foster embodied exploration. For critical urban theory and critical digital pedagogy more widely, it offers an empirical and conceptual intervention that challenges the reduction of urban subjects to data points or consumers, reimagining them instead as epistemic agents whose everyday practices can inform more inclusive and situated approaches to urban governance, planning, and education. An implication for urban policy, then, points to the need for cities to create more inclusive infrastructures for transient populations, enabling urban learning experiences that are not overdetermined by proprietary digital systems.

By foregrounding international students as active navigators of hybrid urban-platform ecologies, this approach opens space for an alternative politics of learning and knowledge, one that values everyday acts of belonging, orientation, and agency. Future research could expand this lens to encompass more diverse student cohorts across various urban contexts, thereby deepening our understanding of how transient and mobile populations shape—and are shaped by—the evolving pedagogies of the city.