Screening for Congenital Hip Dislocation—An Overview

Abstract

History of neonatal screening

Epidemiology and etiology

Screening techniques

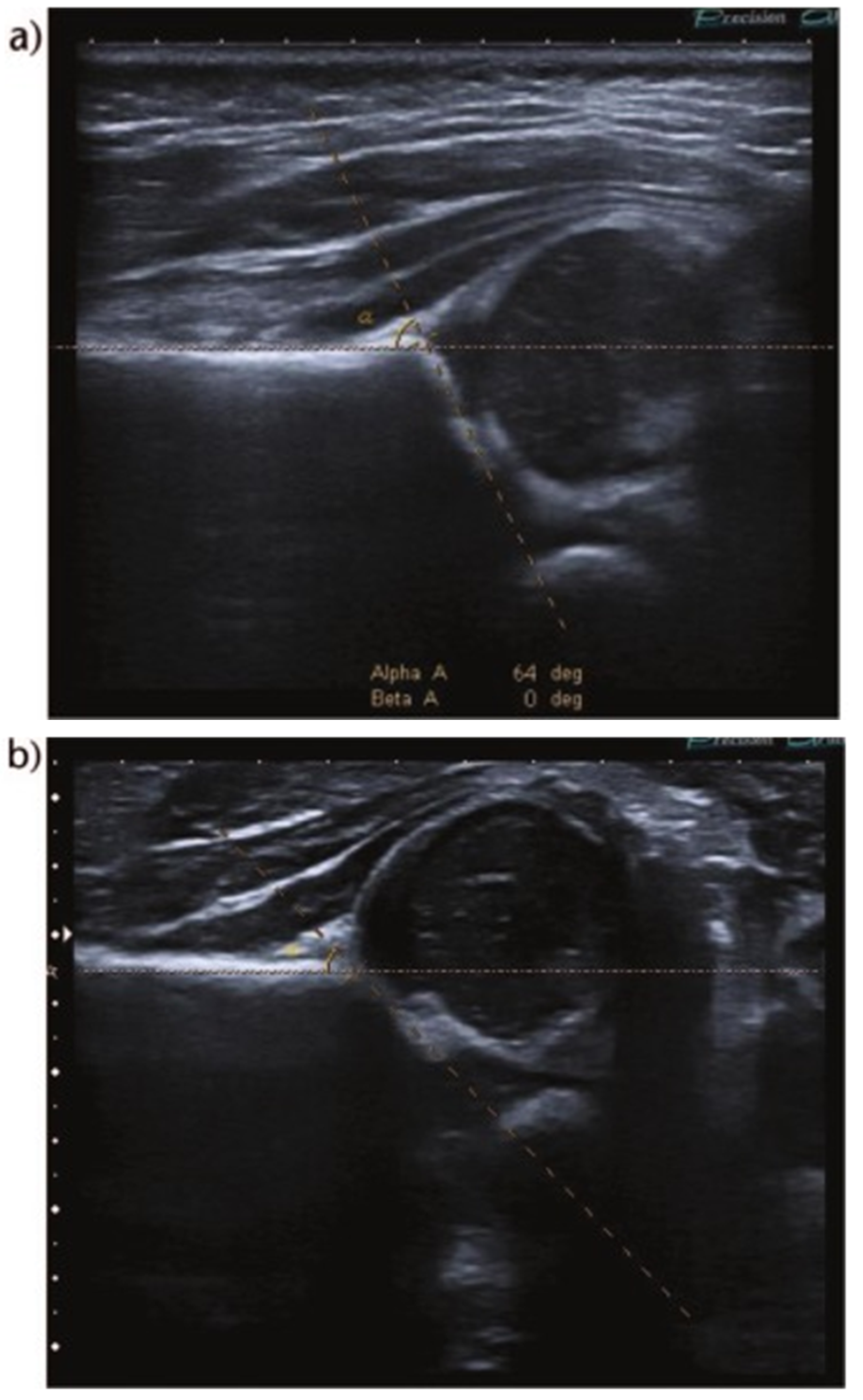

- type I

- ○

- centered hip

- ○

- alpha angle >60° (normal)

- ■

- type Ia: beta angle <55°

- ■

- type Ib: beta angle >55°

- type II

- ○

- centered hip

- ○

- type IIa (physiologically immature): alpha angle 50-59° (<3 months)

- ○

- type IIb: alpha angle 50-59° (>3 months)

- ○

- type IIc

- ■

- alpha angle 43-49°

- ■

- beta angle <77°

- type D (“about to decentre”)

- ○

- alpha angle 43-49°

- ○

- beta angle >77°

- type III

- ○

- decentred hip

- ○

- alpha angle: not measured in a decentred hip

- ○

- cartilage roof pushed partly upwards (cephalad), partly downwards (caudal)

- ○

- perichondrium goes upward (ultrasound image set as right hip AP)

- ■

- type IIIa: no echos in cartilaginous roof

- ■

- type IIIb: echos in cartilaginous roof due to structural alteration and damage

- type IV

- ○

- decentred hip

- ○

- alpha angle: not measured in a decentred hip

- ○

- cartilage roof pushed entirely downwards (cephalad)

- ○

- perichondrium goes horizontal (ultrasound image set as right hip AP)

- ○

Conclusions

References

- Adams, F. The Genuine Works of Hippocrates. New York, 1886; Volume 2, pp. 131–132. [Google Scholar]

- Specht, E.E. Congenital dislocation of the hip. West J Med. 1976, 124, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wenger, D.R.; Bomar, J.D. Historical Aspects of DDH. Indian J Orthop. 2021, 55, 1360–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walter, S.G.; Ossendorff, R.; Yagdiran, A.; Hockmann, J.; Bornemann, R.; Placzek, S. Four decades of developmental dysplastic hip screening according to Graf: What have we learned? Front Pediatr. 2022, 10, 990806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, J.; Li, Y. Progress in screening strategies for neonatal developmental dysplasia of the hip. Front. Surg. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunn, P.M. Perinatal observations on the etiology of congenital dislocation of the hip. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1976, 119, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaquero-Picado, A.; González-Morán, G.; Garay, E.G.; Moraleda, L. Developmental dysplasia of the hip: update of management. EFORT Open Rev. 2019, 4, 548–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramsey, P.L.; Rosenblum, H. Early detection and treatment of congenital hip dislocation. J Bone Joint Surg 1973, 55A, 1312. [Google Scholar]

- Salter, R.B. Etiology, pathogenesis and possible prevention of congenital dislocation of the hip. Can Med Assoc J 1968, 98, 933–945. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Paton, R.W. Screening in Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip (DDH). Surgeon 2017, 15, 290–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paton, R.W. Screening in Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip (DDH). The Surgeon 2017. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barlow, T.G. Early diagnosis and treatment of congenital dislocation of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg 1962, 44-B, 292e301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardiner, H.M.; Dunn, P.M. Controlled trial of immediate splinting versus ultrasonographic surveillance in congenitally dislocatable hips. Lancet 1990, 336, 1553e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaillard, F.; Murphy, A.; Ranchod, A.; et al. Graf method for ultrasound classification of developmental dysplasia of the hip. Reference article, Radiopaedia.org. (accessed on 29 October 2023).

- Andersson, J.E.; Funnemark, P.O. Neonatal hip instability: screening with anterior-dynamic ultrasound method. J Pediatr Orthop 1995, 15, 322e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castelein, R.M.; Sauter, A.J.; de Viieger, M.; et al. Natural history of ultrasound hip abnormalities in clinically normal newborns. J Pediatr Orthop 1992, 12, 423e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sampath, J.S.; Deakin, S.; Paton, R.W. Splintage in developmental dysplasia of the hip. How low can we go? J Pediatr Orthop 2003, 23, 352e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosendahl, K.; Toma, P. Ultrasound in the diagnosis of developmental dysplasia of the hip in newborns. The European approach. A review of methods, accuracy and clinical validity. Eur Radiol 2007, 17, 1960e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wood, M.K.; Conboy, V. , Benson, M.K.D. Does early treatment by abduction splintage improve the development of dysplastic but stable neonatal hips. J Pediatr Orthop 2000, 20, 302e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Mou, X.; Yu, G.; Liang, W.; Cai, C.; Li, X.; Zhang, G. The feasibility of ultrasound Graf method in screening infants and young children with congenital hip dysplasia and follow-up of treatment effect. Translational Pediatrics 2021, 10, 1333–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziegler, C.M.; Ertl, K.M.; Delius, M.; et al. Clinical examination and patients’ history are not suitable for neonatal hip screening. Journal of Children’s Orthopaedics. 2022, 16, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2023 by the author. The materials published in RJMP are protected by copyright. No part of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted in any form or purpose. The manuscripts sent to the RJMP become the property of the publication and the authors declare on their own responsibility that the materials sent are original and have not been sent to other publishing houses.

Share and Cite

Chirilă, R.-I.; Calomfirescu-Avramescu, A.; Dima, V. Screening for Congenital Hip Dislocation—An Overview. Rom. J. Prev. Med. 2023, 2, 7-11. https://doi.org/10.3390/rjpm2030007

Chirilă R-I, Calomfirescu-Avramescu A, Dima V. Screening for Congenital Hip Dislocation—An Overview. Romanian Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2023; 2(3):7-11. https://doi.org/10.3390/rjpm2030007

Chicago/Turabian StyleChirilă, Rodica-Iulia, Andreea Calomfirescu-Avramescu, and Vlad Dima. 2023. "Screening for Congenital Hip Dislocation—An Overview" Romanian Journal of Preventive Medicine 2, no. 3: 7-11. https://doi.org/10.3390/rjpm2030007

APA StyleChirilă, R.-I., Calomfirescu-Avramescu, A., & Dima, V. (2023). Screening for Congenital Hip Dislocation—An Overview. Romanian Journal of Preventive Medicine, 2(3), 7-11. https://doi.org/10.3390/rjpm2030007