Maternal Essentialism and Preschoolers’ Executive Functioning: Indirect Effects Through Parenting Stress and Behavior

Abstract

1. Introduction

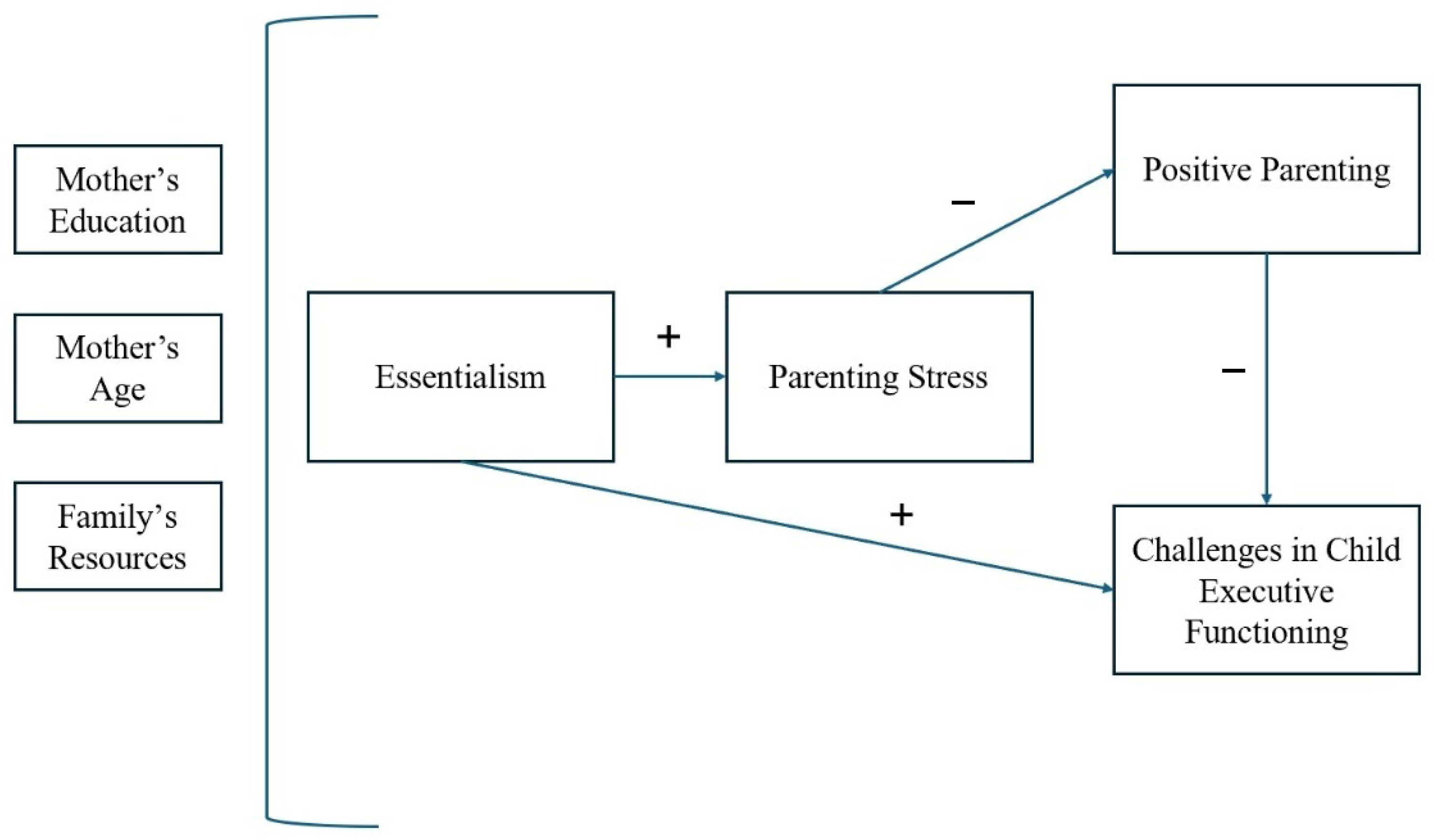

1.1. Conceptual Framework

1.2. Background and Significance

1.2.1. Maternal Essentialism as a Distal Ideological Stressor

1.2.2. Parenting Stress and Positive Parenting as Proximal Processes

1.2.3. Positive Parenting and Child Executive Functioning

1.2.4. Current Study

- H1: Higher levels of essentialist beliefs would be associated with higher reports of maternal parenting stress.

- H2: Elevated parenting stress would be associated with lower levels of maternal reports of positive parenting behaviors.

- H3: Lower levels of reported positive parenting behaviors would be associated with greater challenges in children’s EF skills.

- H4: Parenting stress and positive parenting would sequentially explain the association between maternal essentialism and children’s EF skills.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Procedure

2.2. Participants

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Maternal Essentialist Attitudes

2.3.2. Parenting Stress

2.3.3. Positive Parenting Behaviors

2.3.4. Children’s Executive Functioning (EF)

2.4. Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary Analyses

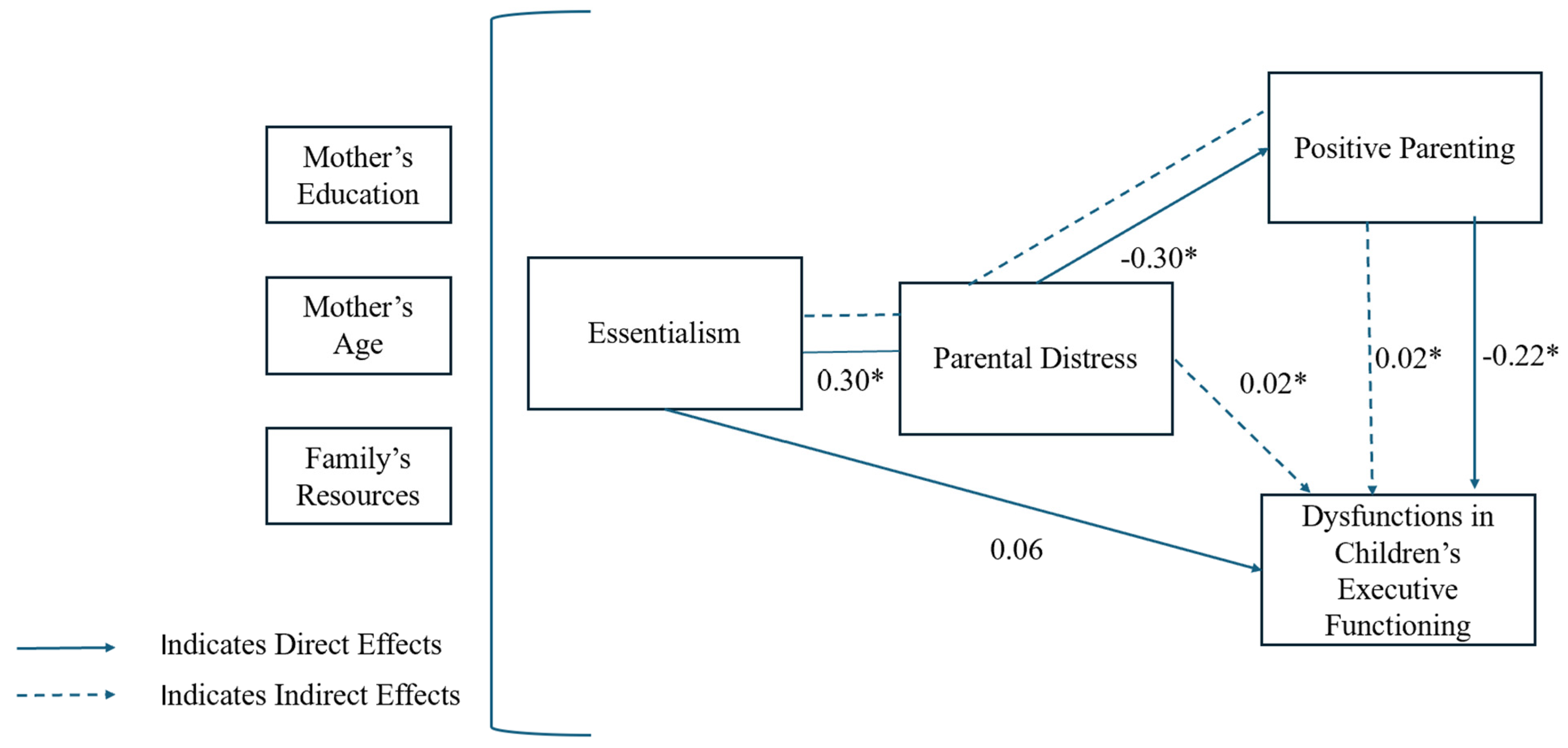

3.2. Model Testing

4. Discussion

4.1. Maternal Essentialism and Parenting Stress

4.2. Maternal Essentialism, Parenting Stress, and Parenting Behaviors

4.3. Gender and Maternal Essentialism

4.4. Implications

4.5. Study Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| IM | Intensive Mothering |

| EF | Executive Functioning |

| Mturk | Amazon Mechanical Turk |

| FSPP | Family Stress-Proximal Process Model |

| IPAQ | Intensive Parenting Attitudes Questionnaire |

| PSI-SF | Parenting Stress Index-Short Form |

| PARYC | Parenting Young Children Questionnaire |

| BRIEF-P | The Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Functioning- Preschool |

| SEM | Structural Equation Modeling |

References

- Abidin, R. R. (2012). Parenting stress index–fourth edition (PSI-4). Psychological Assessment Resources. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, K. R. (2023). Feminist theory, method, and praxis: Toward a critical consciousness for family and close relationship scholars. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 40(3), 899–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthony, L. G., Anthony, B. J., Glanville, D. N., Naiman, D. Q., Waanders, C., & Shaffer, S. (2005). The relationships between parenting stress, parenting behaviour and preschoolers’ social competence and behaviour problems in the classroom. Infant and Child Development, 14(2), 133–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arditti, J. A. (2016). A family stress-proximal process model for understanding the effects of parental incarceration on children and their families. Couple and Family Psychology: Research and Practice, 5(2), 65–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernier, A., Carlson, S. M., & Whipple, N. (2010). From external regulation to self- regulation: Early parenting precursors of young children’s executive functioning. Child Development, 81, 326–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bindman, S. W., Pomerantz, E. M., & Roisman, G. I. (2015). Do children’s executive functions account for associations between early autonomy-supportive parenting and achievement through high school? Journal of Educational Psychology, 107(3), 756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blair, C., Granger, D. A., Willoughby, M., Mills-Koonce, R., Cox, M., Greenberg, M. T., Kivlighan, K. T., Fortunato, C. K., & FLP Investigators. (2011). Salivary cortisol mediates effects of poverty and parenting on executive functions in early childhood. Child Development, 82(6), 1970–1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blair, C., & Raver, C. C. (2015). School readiness and self-regulation: A developmental psychobiological approach. Annual Review of Psychology, 66(1), 711–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blair-Loy, M., Hochschild, A., Pugh, A. J., Williams, J. C., & Hartmann, H. (2015). Stability and transformation in gender, work, and family: Insights from the second shift for the next quarter century. Community, Work & Family, 18(4), 435–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner, U., & Morris, P. A. (1998). The ecology of developmental processes. In W. Damon, & R. M. Lerner (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 1. Theoretical models of human development (5th ed., pp. 993–1028). John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Budds, K., Hogg, M. K., Banister, E. N., & Dixon, M. (2017). Parenting agendas: An empirical study of intensive mothering and infant cognitive development. The Sociological Review, 65(2), 336–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, S. M., Zelazo, P. D., & Faja, S. (2013). Executive function. In P. D. Zelazo (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of developmental psychology, Vol. 1: Body and mind (pp. 706–743). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherry, K. E., Gerstein, E. D., & Ciciolla, L. (2019). Parenting stress and children’s behavior: Transactional models during early head start. Journal of Family Psychology, 33(8), 916–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conger, R. D., Conger, K. J., & Martin, M. J. (2010). Socioeconomic status, family processes, and individual development. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72(3), 685–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crnic, K., & Low, C. (2002). Everyday stresses and parenting. In M. H. Bornstein (Ed.), Handbook of parenting: Vol. 5. Practical issues in parenting (2nd ed., pp. 243–267). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Crnic, K. A. (2024). Parenting stress and child behavior problems: Developmental psychopathology perspectives. Development and Psychopathology, 36(5), 2369–2375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crnic, K. A., & Coburn, S. (2019). Stress and parenting. In M. H. Bornstein (Ed.), Handbook of parenting: Social conditions and applied parenting (3rd ed., vol. 4, pp. 421–448). Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crnic, K. A., Gaze, C., & Hoffman, C. (2005). Cumulative parenting stress across the preschool period: Relations to maternal parenting and child behaviour at age 5. Infant and Child Development, 14, 117–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuevas, K., Deater-Deckard, K., Kim-Spoon, J., Watson, A. J., Morasch, K. C., & Bell, M. A. (2014). What’s mom got to do with it? Contributions of maternal executive function and caregiving to the development of executive function across early childhood. Developmental Science, 17(2), 224–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daundasekara, S. S., Beauchamp, J. E. S., & Hernandez, D. C. (2021). Parenting stress mediates the longitudinal effect of maternal depression on child anxiety/depressive symptoms. Journal of Affective Disorders, 295, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deater-Deckard, K. (1998). Parenting stress and child adjustment: Some old hypotheses and new questions. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 5(3), 314–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamond, A. (2013). Executive functions. Annual Review of Psychology, 64, 135–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunst, C. J., & Leet, H. E. (1987). Measuring the adequacy of resources in households with young children. Child: Care, Health and Development, 13(2), 111–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, S., Powell, R., & Brenton, J. (2015). Being a good mom: Low-income, black single mothers negotiate intensive mothering. Journal of Family Issues, 36(3), 351–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fay-Stammbach, T., Hawes, D. J., & Meredith, P. (2014). Parenting influences on executive function in early childhood: A review. Child Development Perspectives, 8(4), 258–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forbes, L. K., Donovan, C., & Lamar, M. R. (2019). Differences in intensive parenting attitudes and gender norms among U.S. mothers. Family Journal, 28, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauthier, A. H., Bryson, C., Fadel, L., Haux, T., Koops, J., & Mynarska, M. (2021). Exploring the concept of intensive parenting in a three-country study. Demographic Research, 44, 333–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gleeson, J. P., Hsieh, C. M., & Cryer-Coupet, Q. (2016). Social support, family competence, and informal kinship caregiver parenting stress: The mediating and moderating effects of family resources. Children and Youth Services Review, 67, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A. F. (2009). Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Communication Monographs, 76(4), 408–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hays, S. (1996). The cultural contradictions of motherhood. Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hochschild, A. (1989). The second shift: Working parents and the revolution at home. Viking. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, C. (2011). Changes and challenges in 20 years of research into the development of executive functions. Infant and Child Development, 20(3), 251–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishizuka, P. (2019). Social class, gender, and contemporary parenting standards in the United States: Evidence from a national survey experiment. Social Forces, 98, 31–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, D. D., & Swanson, D. H. (2006). Constructing the “good mother”: The experience of mothering ideologies by work status. Sex Roles, 54(7–8), 509–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liss, M., Schiffrin, H. H., Mackintosh, V. H., Miles-McLean, H., & Erchull, M. J. (2013). Development and validation of a quantitative measure of intensive parenting attitudes. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 22(5), 621–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, H., Prikhidko, A., Bendeck, A. C., & Yumusak, S. (2021). Measurement invariance of the intensive parenting attitudes questionnaire across gender and race. Journal of Family Psychology, 35(7), 1027–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubiewska, K., Żegleń, M., Lun, V. M., Park, J., Runge, R., Muller, J., Visser, M., Adair, L., Borualogo, I. S., Orta, I. M., & Głogowska, K. (2025). Intensive parenting of mothers in 11 countries differing in individualism, income inequality, and social mobility. Personality and Individual Differences, 246, 113237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEachern, A. D., Dishion, T. J., Weaver, C. M., Shaw, D. S., Wilson, M. N., & Gardner, F. (2012). Parenting young children (PARYC): Validation of a self-report parenting measure. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 21(3), 498–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGregor, C. M., & Shannon, R. B. (2025). The association between essentialist attitudes and parental distress: A mixed-methods study. Family Relations. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merçon-Vargas, E. A., Lima, R. F. F., Rosa, E. M., & Tudge, J. (2020). Processing proximal processes: What Bronfenbrenner meant, what he didn’t mean, and what he should have meant. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 12(3), 321–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meuwissen, A., & Carlson, S. (2015). Fathers matter: The role of father parenting in preschoolers’ executive function development. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 140, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Musick, K., Meier, A., & Flood, S. (2016). How parents fare: Mothers’ and fathers’ subjective well-being in time with children. American Sociological Review, 81(5), 1069–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthén, B., & Muthén, L. (2017). Mplus. In Handbook of item response theory (pp. 507–518). Chapman and Hall/CRC. [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien Hallstein, D. L. (2006). Conceiving intensive mothering: The Mommy Myth, Maternal Desire, and the lingering vestiges of matrophobia. Journal of the Association for Research on Mothering, 8(1–2), 96–108. [Google Scholar]

- Renegar, V. R., & Cole, K. K. (Eds.). (2023). Refiguring motherhood beyond biology (1st ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, K. M., Schiffrin, H. H., & Liss, M. (2013). Insight into the parenthood paradox: Mental health outcomes of intensive mothering. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 22(5), 614–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romagnoli, A., & Wall, G. (2012). ‘I know I’m a good mom’: Young, low-income mothers’ experiences with risk perception, intensive parenting ideology and parenting education programmes. Health, Risk & Society, 14(3), 273–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiffrin, H. H., Godfrey, H., Liss, M., & Erchull, M. J. (2015). Intensive parenting: Does it have the desired impact on child outcomes? Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24(8), 2322–2331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherman, E. M. S., & Brooks, B. L. (2010). Behavior rating inventory of executive function- preschool version (BRIEF-P): Test review and clinical guidelines for use. Child Neuropsychology, 16(5), 503–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulik, M. J., Blair, C., Mills-Koonce, R., Berry, D., Greenberg, M., & Family Life Project Investigators. (2015). Early parenting and the development of externalizing behavior problems: Longitudinal mediation through children’s executive function. Child Development, 86(5), 1588–1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taraban, L., & Shaw, D. S. (2018). Parenting in context: Revisiting Belsky’s classic process of parenting model in early childhood. Developmental Review, 48, 55–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Census Bureau. (2021, August 12). Improved race and ethnicity measures reveal U.S. population is much more multiracial. Available online: https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2021/08/improved-race-ethnicity-measures-reveal-united-states-population-much-more-multiracial.html (accessed on 18 August 2025).

- U.S. Census Bureau. (2022a, March 24). Educational attainment in the United States: 2021. Available online: https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-releases/2022/educational-attainment.html (accessed on 18 August 2025).

- U.S. Census Bureau. (2022b). Income and poverty in the United States: 2021 (Report P60-277). Available online: https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2022/demo/p60-277.html (accessed on 18 August 2025).

- Valcan, D. S., Davis, H., & Pino-Pasternak, D. (2018). Parental behaviours predicting early childhood executive functions: A meta-analysis. Educational Psychology Review, 30(3), 607–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, S. L., Cepeda, I., Krieger, D., Maggi, S., D’Angiulli, A., Weinberg, J., & Grunau, R. E. (2016). Higher cortisol is associated with poorer executive functioning in preschool children: The role of parenting stress, parent coping and quality of daycare. Child Neuropsychology, 22(7), 853–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wall, G. (2010). Mothers’ experiences with intensive parenting and brain development discourse. Women’s Studies International Forum, 33(3), 253–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zha, J., Li, R., He, H., Fang, P., Huang, R., Xing, T., & Wan, Y. (2024). The chain mediating role of parenting stress and child maltreatment in the association between maternal adverse childhood experiences and executive functions in preschool children: A longitudinal study. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 18(1), 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| n | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|

| Age of mother | ||

| 21–29 | 50 | 19.5 |

| 30–39 | 166 | 65.1 |

| 40–48 | 39 | 15.3 |

| Race | ||

| White | 213 | 83.5 |

| Black/African American | 17 | 6.7 |

| Hispanic or Latinx | 15 | 5.9 |

| Asian | 9 | 3.5 |

| Other | 1 | 0.4 |

| Child Age | ||

| 3 | 92 | 36.1 |

| 4 | 103 | 40.4 |

| 5 | 60 | 23.5 |

| Child Gender | ||

| Girl | 117 | 45.9 |

| Boy | 138 | 54.1 |

| Education Level | ||

| Some high school | 6 | 2.4 |

| High school diploma/GED | 21 | 8.2 |

| Vocational school | 3 | 1.2 |

| Some college | 39 | 15.3 |

| 4-year degree | 94 | 36.9 |

| Graduate degree | 92 | 36.1 |

| Marital Status | ||

| Single | 13 | 5.1 |

| Married | 207 | 81.2 |

| Cohabitating | 17 | 6.7 |

| Separated or divorced | 13 | 5.1 |

| Other | 5 | 2.0 |

| Employment | ||

| Full time | 129 | 50.6 |

| Part time | 32 | 12.5 |

| Unemployed | 73 | 28.6 |

| Other | 21 | 8.2 |

| Income Level | ||

| Lower income | 61 | 23.9 |

| Middle income | 155 | 60.8 |

| Upper income | 39 | 15.3 |

| Variables | V1 | V2 | V3 | V4 | V5 | V6 | V7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mother’s age | 1.00 | 0.35 ** | −0.17 | −0.05 * | 0.15 * | −0.11 | 0.10 |

| Education | 0.35 ** | 1.00 | −0.28 ** | −0.03 | −0.002 | −0.12 | 0.24 ** |

| Essentialism | −0.17 ** | −0.28 ** | 1.00 | 0.37 ** | −0.21 ** | 0.21 ** | −0.39 ** |

| Parenting Stress | −0.05 | −0.03 | 0.37 ** | 1.00 | −0.34 ** | 0.36 ** | −0.35 ** |

| Positive parenting | 0.15 * | −0.002 | −0.21 ** | −0.34 ** | 1.00 | −0.32 ** | 0.21 ** |

| Challenges in EF | −0.11 | −0.12 | 0.21 ** | 0.36 ** | −0.32 ** | 1.00 | −0.20 ** |

| Total resources | 0.10 | 0.24 ** | −0.39 ** | −0.35 ** | 0.21 ** | −0.20 ** | 1.00 |

| Means (SD) | 33.96 (5.05) | 5.84 (1.29) | 2.86 (1.23) | 30.61 (9.00) | 5.73 (0.69) | 53.75 (12.35) | 132.11 (14.16) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

McGregor, C.M.; Arditti, J.A.; Shannon, R.B.; Blalock, J. Maternal Essentialism and Preschoolers’ Executive Functioning: Indirect Effects Through Parenting Stress and Behavior. Fam. Sci. 2025, 1, 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/famsci1020009

McGregor CM, Arditti JA, Shannon RB, Blalock J. Maternal Essentialism and Preschoolers’ Executive Functioning: Indirect Effects Through Parenting Stress and Behavior. Family Sciences. 2025; 1(2):9. https://doi.org/10.3390/famsci1020009

Chicago/Turabian StyleMcGregor, Casey M., Joyce A. Arditti, Rachel B. Shannon, and Jamie Blalock. 2025. "Maternal Essentialism and Preschoolers’ Executive Functioning: Indirect Effects Through Parenting Stress and Behavior" Family Sciences 1, no. 2: 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/famsci1020009

APA StyleMcGregor, C. M., Arditti, J. A., Shannon, R. B., & Blalock, J. (2025). Maternal Essentialism and Preschoolers’ Executive Functioning: Indirect Effects Through Parenting Stress and Behavior. Family Sciences, 1(2), 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/famsci1020009