Evaluation of the Biostimulant Effect of Sinorhizobium meliloti on Grapevine Under Rational and Deficit Irrigation †

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

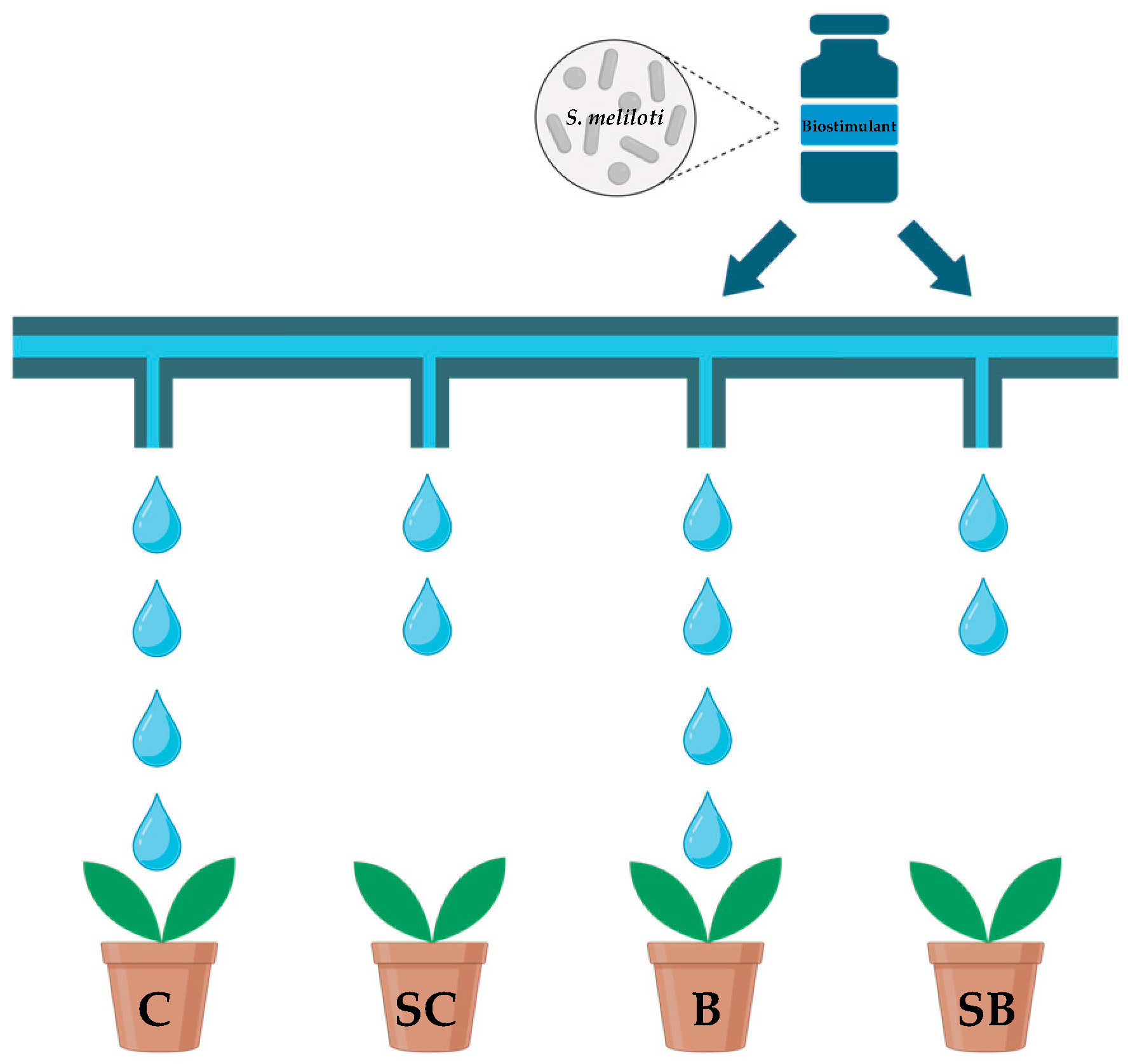

2.1. Experimental Design

2.2. Determination of Metabolic and Growth Parameters

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

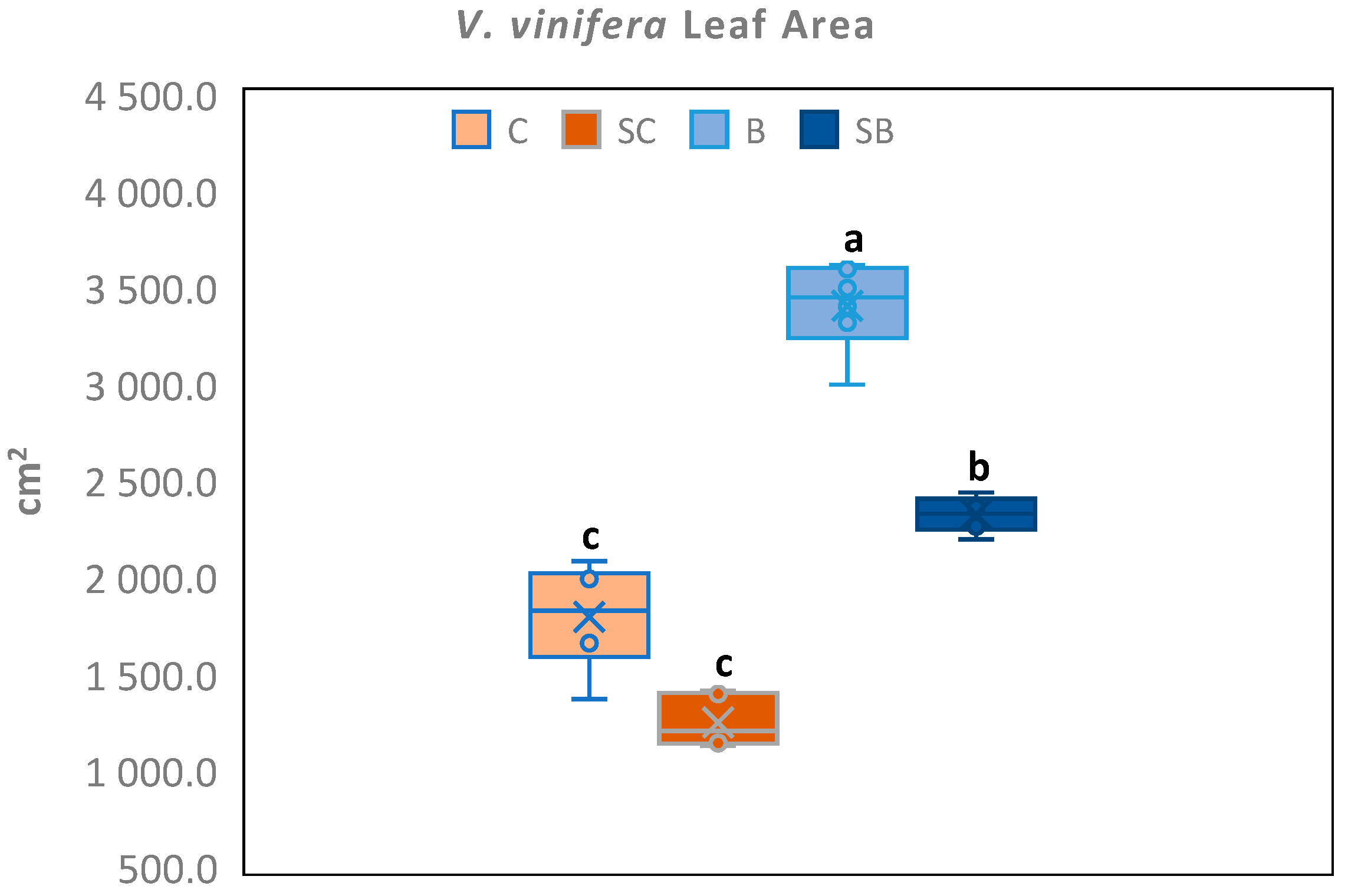

3.1. Leaf Area

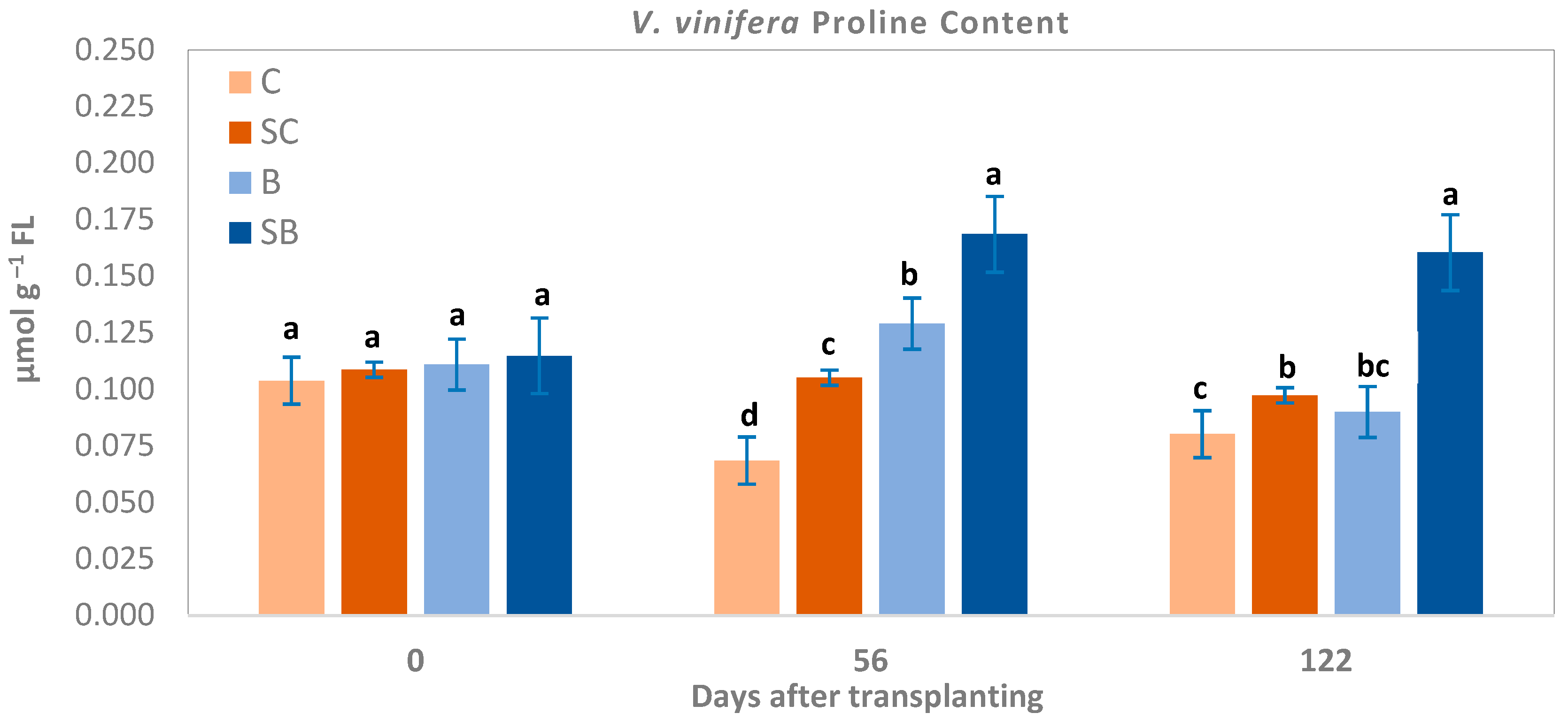

3.2. Proline Content

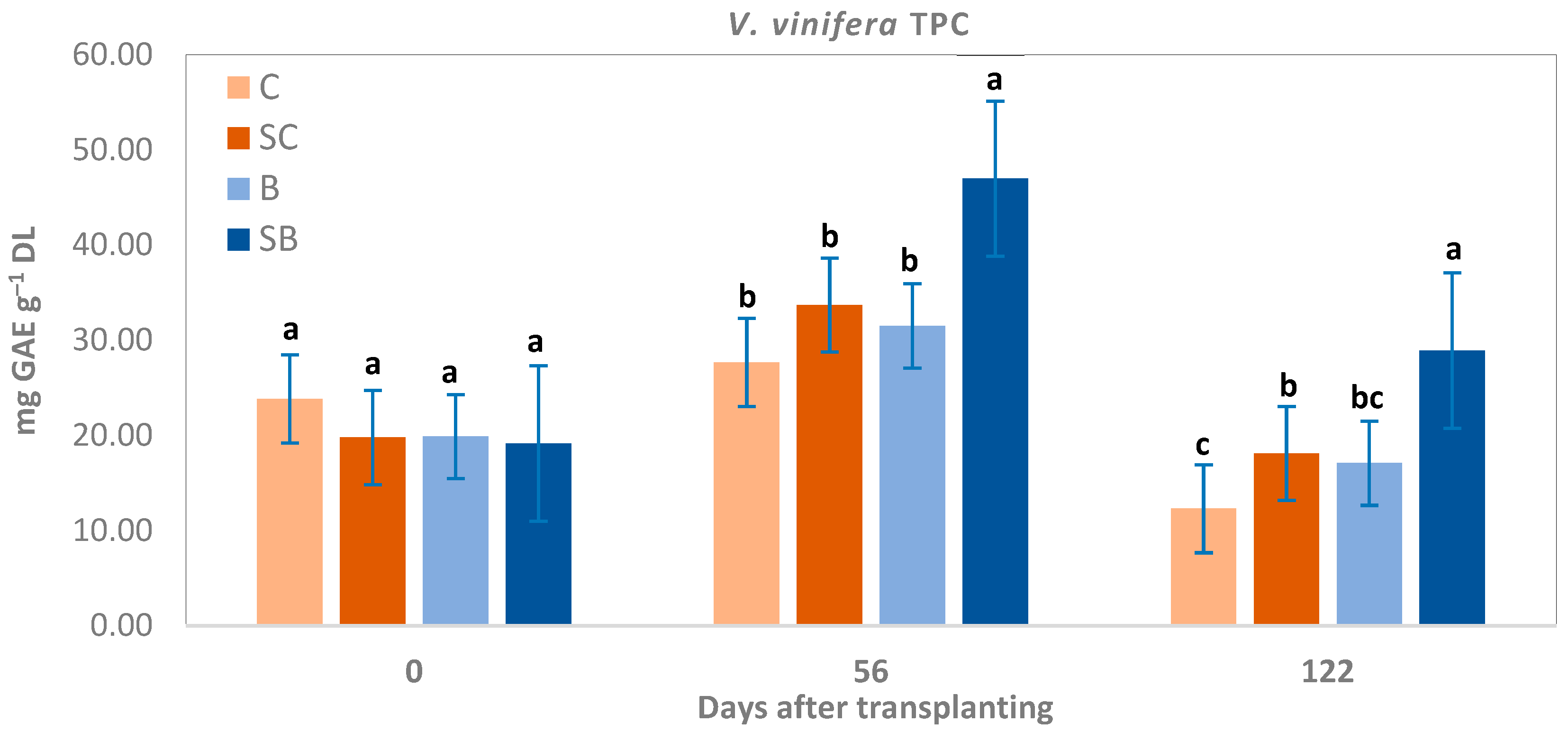

3.3. Total Phenolic Content

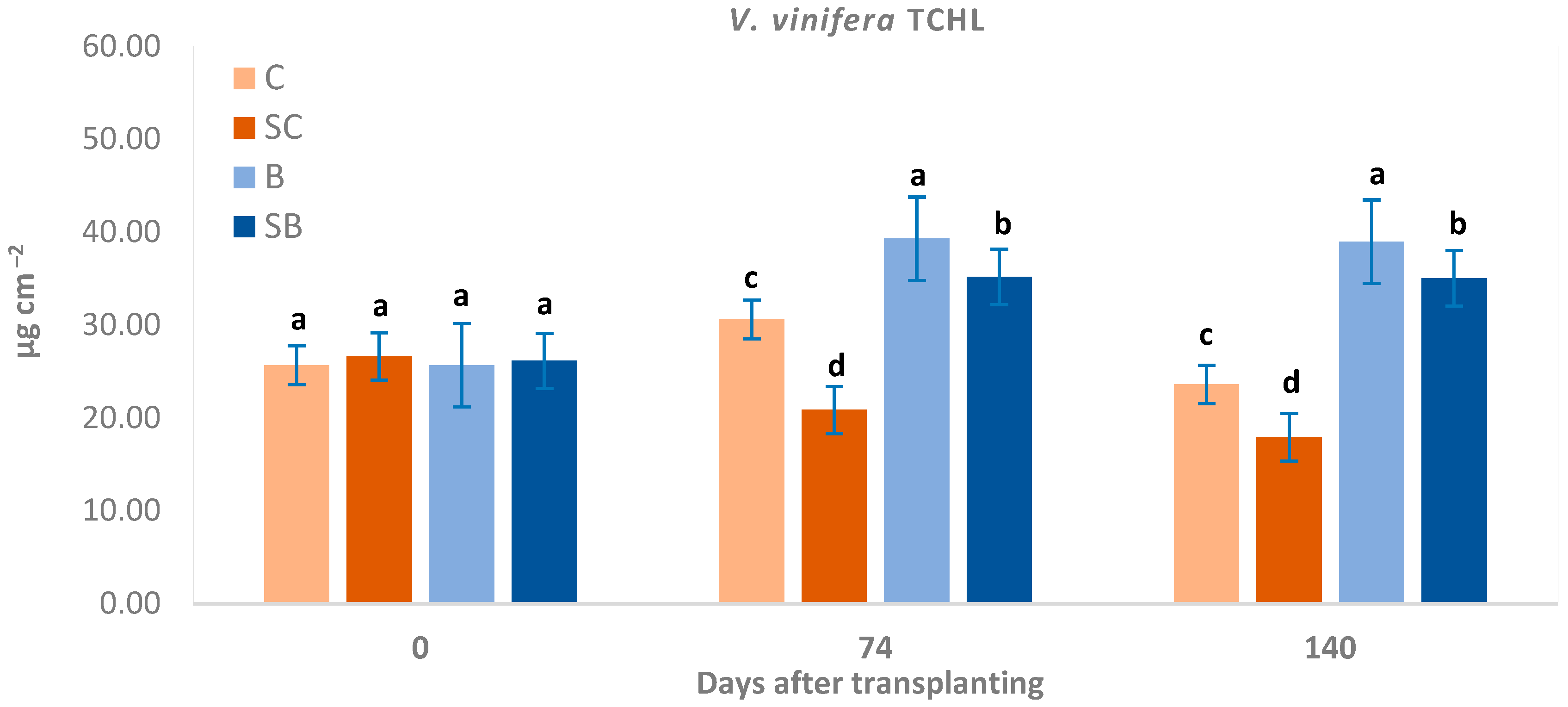

3.4. Total Chlorophyll Content

4. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Roby, G.; Harbertson, J.F.; Adams, D.A.; Matthews, M.A. Berry Size and Vine Water Deficits as Factors in Winegrape Composition: Anthocyanins and Tannins. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2004, 10, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, D.M.; Roby, G.; Ebeler, S.E.; Guinard, J.X.; Matthews, M.A. Sensory Attributes of Cabernet Sauvignon Wines Made from Vines with Different Water Status. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2005, 11, 339–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naulleau, A.; Gary, C.; Prévot, L.; Hossard, L. Evaluating Strategies for Adaptation to Climate Change in Grapevine Production—A Systematic Review. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 11, 607859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrizabalaga-Arriazu, M.; Morales, F.; Irigoyen, J.J.; Hilbert, G.; Pascual, I. Growth Performance and Carbon Partitioning of Grapevine Tempranillo Clones under Simulated Climate Change Scenarios: Elevated CO2 and Temperature. J. Plant Physiol. 2020, 252, 153226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kizildeniz, T.; Mekni, I.; Santesteban, H.; Pascual, I.; Morales, F.; Irigoyen, J.J. Effects of Climate Change Including Elevated CO2 Concentration, Temperature and Water Deficit on Growth, Water Status, and Yield Quality of Grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.) Cultivars. Agric. Water Manag. 2015, 159, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteverde, C.; De Sales, F. Impacts of Global Warming on Southern California’s Winegrape Climate Suitability. Adv. Clim. Change Res. 2020, 11, 279–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellarin, S.D.; Matthews, M.A.; Di Gaspero, G.; Gambetta, G.A. Water Deficits Accelerate Ripening and Induce Changes in Gene Expression Regulating Flavonoid Biosynthesis in Grape Berries. Planta 2007, 227, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deluc, L.G.; Quilici, D.R.; Decendit, A.; Grimplet, J.; Wheatley, M.D.; Schlauch, K.A.; Mérillon, J.M.; Cushman, J.C.; Cramer, G.R. Water Deficit Alters Differentially Metabolic Pathways Affecting Important Flavor and Quality Traits in Grape Berries of Cabernet Sauvignon and Chardonnay. BMC Genom. 2009, 10, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alatzas, A.; Theocharis, S.; Miliordos, D.E.; Leontaridou, K.; Kanellis, A.K.; Kotseridis, Y.; Hatzopoulos, P.; Koundouras, S. The Effect of Water Deficit on Two Greek Vitis vinifera L. Cultivars: Physiology, Grape Composition and Gene Expression during Berry Development. Plants 2021, 10, 1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rouphael, Y.; Colla, G. Editorial: Biostimulants in Agriculture. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calvo, P.; Nelson, L.; Kloepper, J.W. Agricultural Uses of Plant Biostimulants. Plant Soil. 2014, 383, 3–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadiji, A.E.; Babalola, O.O.; Santoyo, G.; Perazzolli, M. The Potential Role of Microbial Biostimulants in the Amelioration of Climate Change-Associated Abiotic Stresses on Crops. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 829099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangiorgio, D.; Cellini, A.; Donati, I.; Pastore, C.; Onofrietti, C.; Spinelli, F. Facing Climate Change: Application of Microbial Biostimulants to Mitigate Stress in Horticultural Crops. Agronomy 2020, 10, 794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolandnazar, S.; Sharghi, A.; Naghdi Badhi, H.; Mehrafarin, A.; Sarikhani, M.R. The Impact of Sinorhizobium Meliloti and Pseudomonas Fluorescens on Growth, Seed Yield and Biochemical Product of Fenugreek under Water Deficit Stress. Adv. Hortic. Sci. 2018, 32, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mus, F.; Crook, M.B.; Garcia, K.; Costas, A.G.; Geddes, B.A.; Kouri, E.D.; Paramasivan, P.; Ryu, M.H.; Oldroyd, G.E.D.; Poole, P.S.; et al. Symbiotic Nitrogen Fixation and the Challenges to Its Extension to Nonlegumes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2016, 82, 3698–3710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Liu, J.; Zhu, H. Genetic and Molecular Mechanisms Underlying Symbiotic Specificity in Legume-Rhizobium Interactions. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 334639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velásquez, A.; Vega-Celedón, P.; Fiaschi, G.; Agnolucci, M.; Avio, L.; Giovannetti, M.; D’Onofrio, C.; Seeger, M. Responses of Vitis vinifera Cv. Cabernet Sauvignon Roots to the Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungus Funneliformis Mosseae and the Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacterium Ensifer Meliloti Include Changes in Volatile Organic Compounds. Mycorrhiza 2020, 30, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galleguillos, C.; Aguirre, C.; Miguel Barea, J.; Azcón, R. Growth Promoting Effect of Two Sinorhizobium Meliloti Strains (a Wild Type and Its Genetically Modified Derivative) on a Non-Legume Plant Species in Specific Interaction with Two Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi. Plant Sci. 2000, 159, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, Z.; Deng, Z.; Glick, B.R.; Wei, G.; Chou, M. A Nodule Endophytic Plant Growth-Promoting Pseudomonas and Its Effects on Growth, Nodulation and Metal Uptake in Medicago Lupulina under Copper Stress. Ann. Microbiol. 2017, 67, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavadia, A.; Omirou, M.; Fasoula, D.A.; Louka, F.; Ehaliotis, C.; Ioannides, I.M. Co-Inoculations with Rhizobia and Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi Alters Mycorrhizal Composition and Lead to Synergistic Growth Effects in Cowpea That Are Fungal Combination-Dependent. Appl. Soil. Ecol. 2021, 167, 104013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddling, J.; Gelang-Alfredsson, J.; Piikki, K.; Pleijel, H. Evaluating the Relationship between Leaf Chlorophyll Concentration and SPAD-502 Chlorophyll Meter Readings. Photosynth. Res. 2007, 91, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenthaler, H.K.; Buschmann, C. Chlorophylls and Carotenoids: Measurement and Characterization by UV-VIS Spectroscopy. Curr. Protoc. Food Anal. Chem. 2001, 1, F4.3.1–F4.3.8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katalinic, V.; Mozina, S.S.; Generalic, I.; Skroza, D.; Ljubenkov, I.; Klancnik, A. Phenolic Profile, Antioxidant Capacity, and Antimicrobial Activity of Leaf Extracts from Six Vitis vinifera L. Varieties. Int. J. Food Prop. 2013, 16, 45–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papantzikos, V.; Papanikou, A.; Stournaras, V.; Mpeza, P.; Mantzoukas, S.; Patakioutas, G. Biostimulant Effect of Commercial Rhizobacteria Formulation on the Growth of Vitis vinifera L.: Case of Optimal and Water Deficit Conditions. Appl. Biosci. 2024, 3, 151–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakr, E.M. A New Software for Measuring Leaf Area, and Area Damaged by Tetranychus Urticae Koch. J. Appl. Entomol. 2005, 129, 173–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolli, E.; Marasco, R.; Vigani, G.; Ettoumi, B.; Mapelli, F.; Deangelis, M.L.; Gandolfi, C.; Casati, E.; Previtali, F.; Gerbino, R.; et al. Improved Plant Resistance to Drought Is Promoted by the Root-Associated Microbiome as a Water Stress-Dependent Trait. Environ. Microbiol. 2015, 17, 316–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theocharis, A.; Bordiec, S.; Fernandez, O.; Paquis, S.; Dhondt-Cordelier, S.; Baillieul, F.; Clément, C.; Barka, E.A. Burkholderia Phytofirmans PsJN Primes Vitis vinifera L. and Confers a Better Tolerance to Low Nonfreezing Temperatures. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2012, 25, 241–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eswaran, S.U.D.; Sundaram, L.; Perveen, K.; Bukhari, N.A.; Sayyed, R.Z. Osmolyte-Producing Microbial Biostimulants Regulate the Growth of Arachis hypogaea L. under Drought Stress. BMC Microbiol. 2024, 24, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lephatsi, M.; Nephali, L.; Meyer, V.; Piater, L.A.; Buthelezi, N.; Dubery, I.A.; Opperman, H.; Brand, M.; Huyser, J.; Tugizimana, F. Molecular Mechanisms Associated with Microbial Biostimulant-Mediated Growth Enhancement, Priming and Drought Stress Tolerance in Maize Plants. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 10450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bittencourt, P.P.; Alves, A.F.; Ferreira, M.B.; da Silva Irineu, L.E.S.; Pinto, V.B.; Olivares, F.L. Mechanisms and Applications of Bacterial Inoculants in Plant Drought Stress Tolerance. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozdemir, G.; Kitir, N.; Turan, M.; Ozlu, E. Impacts of Organic and Organo-Mineral Fertilizers on Total Phenolic, Flavonoid, Anthocyanin and Antiradical Activity of Okuzgozu (Vitis vinifera L.) Grapes. Acta Sci. Pol. Hortorum Cultus 2018, 17, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, M.A.; Mishra, A.K.; Jan, S.; Bhat, M.A.; Kamal, M.A.; Rahman, S.; Shah, A.A.; Jan, A.T. Plant Growth Promoting Rhizobacteria in Plant Health: A Perspective Study of the Underground Interaction. Plants 2023, 12, 629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianco, C.; Defez, R. Medicago Truncatula Improves Salt Tolerance When Nodulated by an Indole-3-Acetic Acid-Overproducing Sinorhizobium Meliloti Strain. J. Exp. Bot. 2009, 60, 3097–3107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahwar, D.; Mushtaq, Z.; Mushtaq, H.; Alqarawi, A.A.; Park, Y.; Alshahrani, T.S.; Faizan, S. Role of Microbial Inoculants as Bio Fertilizers for Improving Crop Productivity: A Review. Heliyon 2023, 9, e16134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Li, X.L.; Luo, L. Effects of Engineered Sinorhizobium Meliloti on Cytokinin Synthesis and Tolerance of Alfalfa to Extreme Drought Stress. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012, 78, 8056–8061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asari, S.; Tarkowská, D.; Rolčík, J.; Novák, O.; Palmero, D.V.; Bejai, S.; Meijer, J. Analysis of Plant Growth-Promoting Properties of Bacillus Amyloliquefaciens UCMB5113 Using Arabidopsis Thaliana as Host Plant. Planta 2017, 245, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alina, S.O.; Constantinscu, F.; Petruța, C.C. Biodiversity of Bacillus Subtilis Group and Beneficial Traits of Bacillus Species Useful in Plant Protection. Rom. Biotechnol. Lett. 2015, 20, 10737–10750. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Papantzikos, V. Evaluation of the Biostimulant Effect of Sinorhizobium meliloti on Grapevine Under Rational and Deficit Irrigation. Environ. Earth Sci. Proc. 2026, 40, 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/eesp2026040001

Papantzikos V. Evaluation of the Biostimulant Effect of Sinorhizobium meliloti on Grapevine Under Rational and Deficit Irrigation. Environmental and Earth Sciences Proceedings. 2026; 40(1):1. https://doi.org/10.3390/eesp2026040001

Chicago/Turabian StylePapantzikos, Vasileios. 2026. "Evaluation of the Biostimulant Effect of Sinorhizobium meliloti on Grapevine Under Rational and Deficit Irrigation" Environmental and Earth Sciences Proceedings 40, no. 1: 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/eesp2026040001

APA StylePapantzikos, V. (2026). Evaluation of the Biostimulant Effect of Sinorhizobium meliloti on Grapevine Under Rational and Deficit Irrigation. Environmental and Earth Sciences Proceedings, 40(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/eesp2026040001