Promoting Urban Community Gardens as “Third Places”: Lessons from Toronto and São Paulo

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Research Question

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Toronto and São Paulo

3.2. Data Collection

4. Results

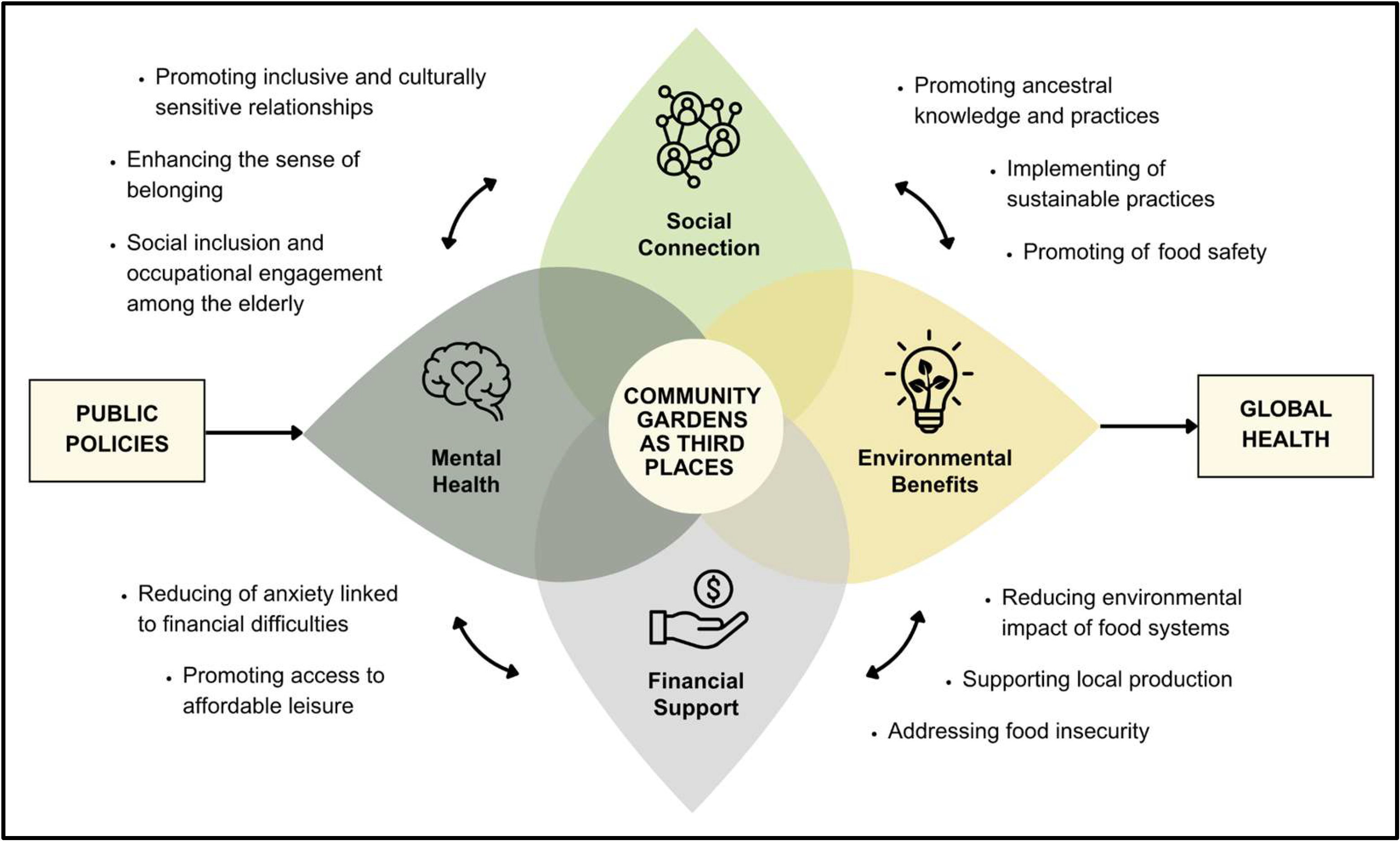

4.1. Social Connection

4.2. Financial Support

4.3. Environmental Sustainability

4.4. Mental Health

5. Discussion

5.1. UCGs as Third Places: Nurturing Culture, Belonging, and Well-Being

5.2. Facilitators and Barriers in Developing UCGs

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| UCG | Urban community gardens |

References

- Oldenburg, R. The Great Good Place: Cafés, Coffee Shops, Bookstores, Bars, Hair Salons, and Other Hangouts at the Heart of a Community; Da Capo Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1999; ISBN 9781569246818. [Google Scholar]

- School Mental Health Ontario. What’s Your Third Place? Available online: https://smho-smso.ca/whats-your-third-place/ (accessed on 13 June 2025).

- City of Toronto. Community Garden Action Plan. Available online: https://www.toronto.ca/legdocs/1999/agendas/council/cc/cc990706/edp1rpt/cl009.htm (accessed on 13 June 2025).

- Statistics Canada. Census Profile, 2021 Census of Population. Available online: https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2021/dp-pd/prof/details/page.cfm?Lang=E&GENDERlist=1&STATISTIClist=1&HEADERlist=0&DGUIDlist=2021A00053520005&SearchText=toronto (accessed on 23 April 2025).

- Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (IBGE). Panorama São Paulo. Available online: https://cidades.ibge.gov.br/brasil/sp/sao-paulo/panorama (accessed on 23 April 2025).

- City of São Paulo. City of São Paulo | PROFILE 2019; International Organization for Migration (IOM): Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- City of Toronto. Community Gardens. Available online: https://www.toronto.ca/explore-enjoy/parks-recreation/places-spaces/beaches-gardens-attractions/gardens-and-horticulture/community-gardens/ (accessed on 25 July 2024).

- FoodShare. Toronto Community Garden FAQ. Available online: https://foodshare.net/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/Community_Garden_FAQ.pdf (accessed on 11 August 2025).

- Cidade de São Paulo. Sampa+Rural. Available online: https://sampamaisrural.prefeitura.sp.gov.br (accessed on 11 August 2025).

- Dalglish, S.L.; Khalid, H.; McMahon, S.A. Document Analysis in Health Policy Research: The READ Approach. Health Policy Plan. 2020, 35, 1424–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhuang, Z.; Lok, R. Aging in Third Places: Community Spaces and Social Infrastructure for Older Immigrants. In Intersections of Aging and Immigration: The Promise and Paradox of a Better Life; Sepali, G., Ed.; Toronto Metropolitan University: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2024; p. 246. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, D.; Drescher, M. Urban Crops and Livestock: The Experiences, Challenges, and Opportunities of Planning for Urban Agriculture in Two Canadian Provinces. Land Use Policy 2015, 43, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biazoti, A.R.; Sorrentino, M. Political Engagement in Urban Agriculture: Power to Act in Community Gardens of São Paulo. Ambiente Sociedade 2022, 25, e0056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagib, G. Processos e Materialização da Agricultura Urbana como Ativismo na Cidade de São Paulo: O Caso da Horta das Corujas. Cad. Metrópole 2019, 21, 715–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedro, A.A.; Görner, A.; Lindner, A.; Wende, W. “More than Fruits and Vegetables”: Community Garden Experiences from the Global North to Foster Green Development of Informal Areas in Sao Paulo, Brazil. Res. Urban. Ser. 2020, 6, 219–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagib, G.; Nakamura, A.C. Urban Agriculture in the City of São Paulo: New Spatial Transformations and Ongoing Challenges to Guarantee the Production and Consumption of Healthy Food. Glob. Food Secur. 2020, 26, 100378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldas, L.C.; Christopoulos, T.P. Social Capital in Urban Agriculture Initiatives. Revista de Gestão 2022, 30, 92–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- City of Toronto. Community Gardens. Available online: https://jobs.toronto.ca/recreation/content/Community-Gardens/?locale=en_US (accessed on 13 June 2025).

- Robillard, P.; Şekercioğlu, F.; Edge, S.; Young, I. Resilience in the Face of Crisis: Investigating COVID-19 Impacts on Urban Community Gardens in Greater Toronto Area, Canada. Br. Food J. 2023, 125, 4048–4061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, M.A.; Bonaci, W.D.B.S.; Foganholo, L.S. Horta Comunitária e Psicologia Social: Um Relato de Experiência. Fract. Rev. Psicol. 2022, 34, e29430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, V.; Gough, W.A.; Agic, B. Nature-Based Equity: An Assessment of the Public Health Impacts of Green Infrastructure in Ontario Canada. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacob, M.; Rocha, C. Models of Governance in Community Gardening: Administrative Support Fosters Project Longevity. Local Environ. 2021, 26, 557–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dantas, K.C.; Zembruski, P.S.; Kubrusly, M.S.; Carvalho-Oliveira, R.; Mauad, T. Four Years of Experience with the Sao Paulo University Medical School Community Garden. In World Sustainability Series; Leal Filho, W., Frankenberger, F., Iglecias, P., Mülfarth, R., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 427–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- City of Toronto. A Guide to Growing and Selling Fresh Fruits and Vegetables in Toronto; Toronto Food Policy Council: Toronto, ON, USA, 2019; p. 18. [Google Scholar]

- Prefeitura de São Paulo. Hortas Escolares. Available online: https://educacao.sme.prefeitura.sp.gov.br/programa-de-alimentacao-escolar/educacao-alimentar-e-nutricional/hortas-escolares/ (accessed on 14 June 2025).

- Prefeitura de São Paulo. Hortas Nas Escolas Municipais de SP Contribuem Com Merenda E “Alimentam” Atividades Pedagógicas. Available online: https://educacao.sme.prefeitura.sp.gov.br/noticias/hortas-nas-escolas-municipais-de-sp-contribuem-com-merenda-e-alimentam-atividades-pedagogicas/ (accessed on 14 June 2025).

- City of Toronto. From the Ground Up: Guide for Soil Testing in Urban Gardens; Toronto Public Health: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Sussa, F.V.; Furlan, M.R.; Victorino, M.; Filgueira, R.; Silva, P. Essential and Non-Essential Elements in Lettuce Produced on a Rooftop Urban Garden in São Paulo Metropolitan Region (Brazil) and Assessment of Human Health Risks. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 2022, 331, 5869–5879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amato-Lourenço, L.F.; Saiki, M.; Saldiva, P.H.N.; Mauad, T. Influence of Air Pollution and Soil Contamination on the Contents of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) in Vegetables Grown in Urban Gardens of Sao Paulo, Brazil. Front. Environ. Sci. 2017, 5, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, C.G.A.; Garcia, M.T.; Ribeiro, S.M.; de Salandini, M.F.S.; Bógus, C.M. Hortas Comunitárias Como Atividade Promotora de Saúde: Uma Experiência em Unidades Básicas de Saúde. Ciência Saúde Coletiva 2015, 20, 3099–3110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wood, C.J.; Polley, M.; Barton, J.L.; Wicks, C.L. Therapeutic Community Gardening as a Green Social Prescription for Mental Ill-Health: Impact, Barriers, and Facilitators from the Perspective of Multiple Stakeholders. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- BC Healthy Communities Healthy Social Environments Framework. Available online: https://bchealthycommunities.ca/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/SE-Framework-Summary-V1-Dec2020.pdf (accessed on 11 August 2025).

- Fairholm, J. Urban Agriculture and Food Security Initiatives in Canada: A Survey of Canadian Non-Governmental Organizations; International Development Research Centre: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 1999; p. 83. [Google Scholar]

| Thematic Axes | Toronto, ON, Canada | São Paulo, SP, Brazil |

|---|---|---|

| Social Connection | ||

| Cultural roots | Communities use their skills and reclaim a sense of home, deeply connected to their cultural heritage [11]. UCGs as a potential tool for promoting community engagement [12]. | UCGs help preserve food heritage by reviving traditional crops and collective, culturally rooted food practices [13,14]. Social and political engagement, sense of belonging and connectedness to the city [13,14,15,16,17]. |

| Leisure | Gardening thrives as a leading leisure activity, and UCGs embody this passion, combining shared stewardship, social connection, and environmental care [3,18,19]. | Participants often describe the activity as enjoyable and meaningful, highlighting its social and recreational benefits [20]. |

| Financial Support | ||

| Employment | Offer diverse employment and leadership opportunities through nature-based programs, workshops, and educational activities for all ages [18]. | Income generation and job opportunities are provided for unemployed individuals and those requiring community reintegration [16,17]. |

| Skills development | Foster hands-on activities that enrich gardening and cooking experiences [21,22]. | In addition to gardening skills, São Paulo’s UCGs offer craft workshops and educational activities that foster entrepreneurship and support life purpose [17,23]. |

| Food security | Food is commonly shared among participants or those in need and may also be sold tax-free [12,24]. | Food may be donated, shared, or sold, contributing to food security and reducing household expenses [15,17,23]. |

| Environmental Sustainability | ||

| Educational role | UCGs act as an educational centre and knowledge base for green technology [22]. | Promotion of sustainable practices among youth through school- and university-based UCG and integrated gardening curriculum [23,25,26]. |

| Food Safety: Air, Soil, and Water Quality | Toronto Public Health developed a guide for soil testing in UCG, providing risk classification and management recommendations based on soil conditions and contaminant levels [27]. Green structures such as UCGs have been reported to have the potential to improve urban microclimate [21]. | Active engagement in global health, as well as valorization of organic farming and the principles of agroecology and permaculture [15,16,17]. Organic food produced in UCGs is safe for consumption [28,29]. |

| Mental Health | ||

| Occupation | Promoted essential aspects such as staying active, fostering social ties, and enhancing skill [18]. | UCGs are reported by women and older adults as opportunities for social belonging and personal fulfillment, offering housewives a sense of purpose beyond family roles and older adults a way to stay active and connected [13,30]. |

| Social prescribing for mental illnesses | Participation in UCG is encouraged as an innovative strategy to promote mental health and mitigate feelings of loneliness [19,31]. | Gardening is often prescribed by healthcare professionals as therapeutic interventions [22,31]. UCGs are built in basic health units’ facilities to promote engagement among patients of the unit [30]. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Valentim, A.B.; Freitas Guimarães, G.; Maia, C.S.C.; Sekercioglu, F. Promoting Urban Community Gardens as “Third Places”: Lessons from Toronto and São Paulo. Reg. Sci. Environ. Econ. 2025, 2, 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/rsee2030027

Valentim AB, Freitas Guimarães G, Maia CSC, Sekercioglu F. Promoting Urban Community Gardens as “Third Places”: Lessons from Toronto and São Paulo. Regional Science and Environmental Economics. 2025; 2(3):27. https://doi.org/10.3390/rsee2030027

Chicago/Turabian StyleValentim, Ashley Brito, Guiomar Freitas Guimarães, Carla Soraya Costa Maia, and Fatih Sekercioglu. 2025. "Promoting Urban Community Gardens as “Third Places”: Lessons from Toronto and São Paulo" Regional Science and Environmental Economics 2, no. 3: 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/rsee2030027

APA StyleValentim, A. B., Freitas Guimarães, G., Maia, C. S. C., & Sekercioglu, F. (2025). Promoting Urban Community Gardens as “Third Places”: Lessons from Toronto and São Paulo. Regional Science and Environmental Economics, 2(3), 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/rsee2030027