Spatiotemporal Activity and Farmers’ Perception of the Red Fox in a Regional Reserve of Central Italy: A Case Study

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

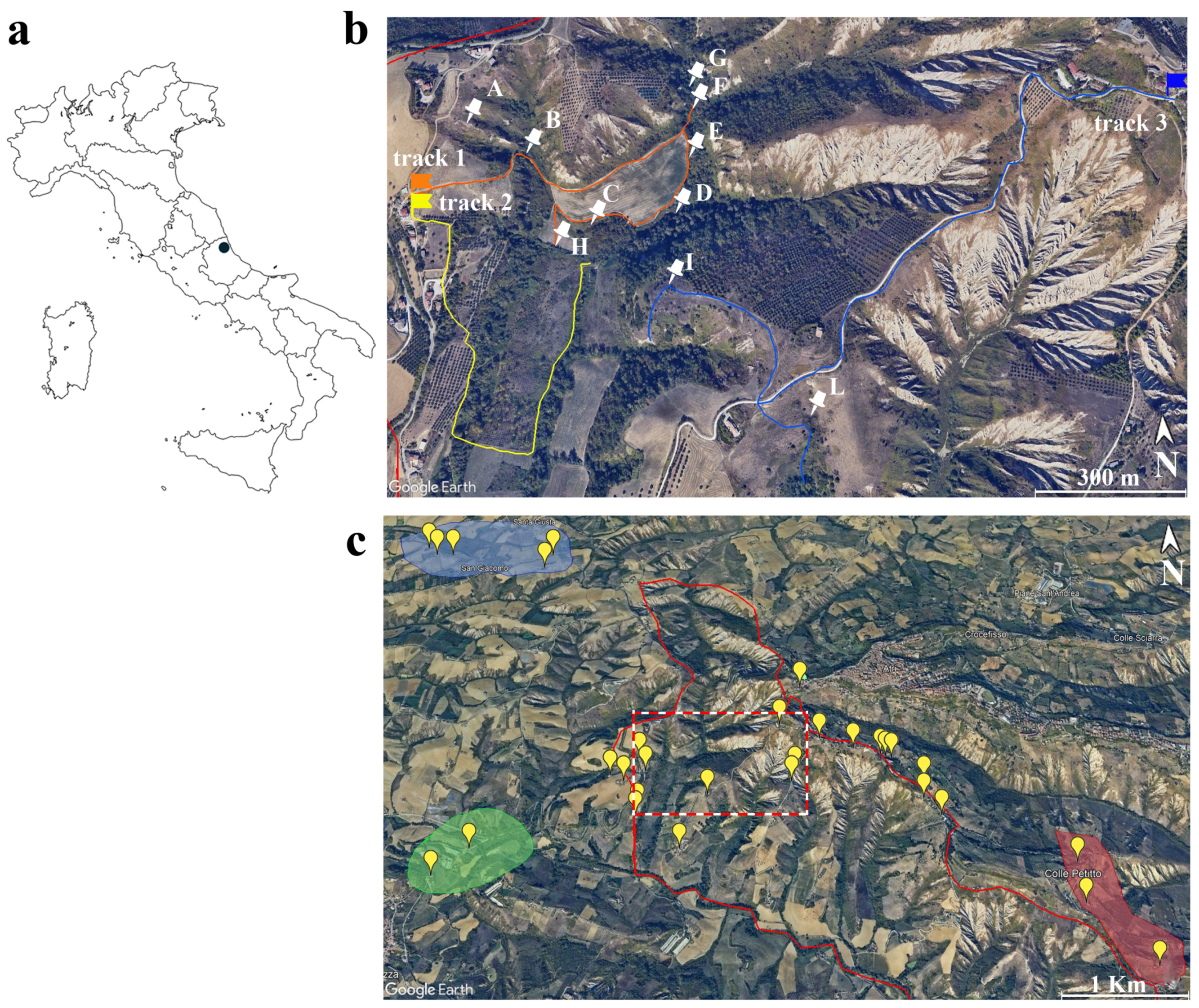

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Camera Trapping and Data Analysis

2.3. Questionary Survey

3. Results

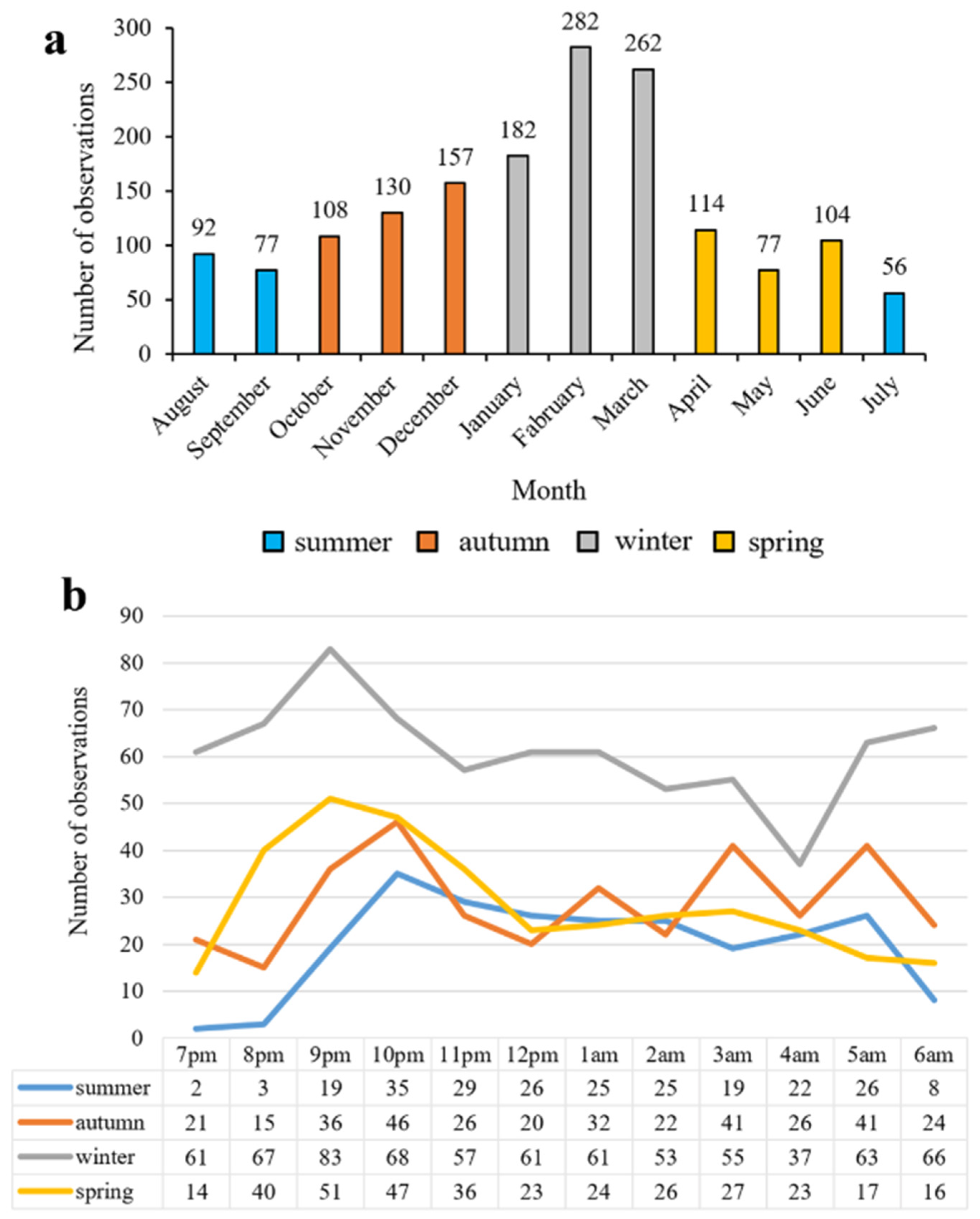

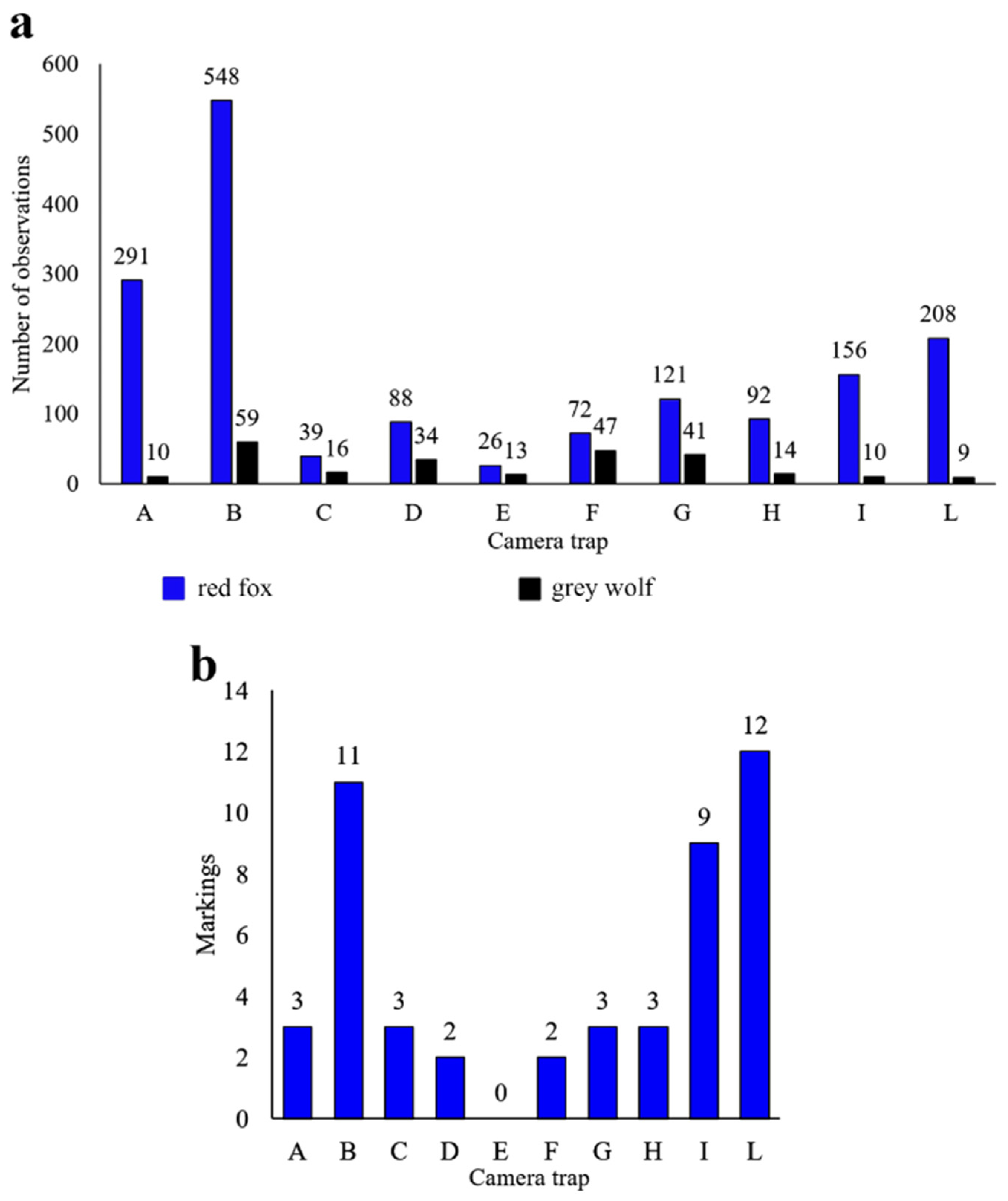

3.1. Temporal and Spatial Patterns of the Red Fox

3.2. Farmers’ Perception of the Red Fox

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Boitani, L.; Lovari, S.; Taglianti, A.V. Mammalia III, Carnivora-Artiodactyla. In Fauna d’Italia; Calderini: Bologna, Italy, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann, M.; Sillero-Zubiri, C. Vulpes vulpes, the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species; IUCN Red List: Cambridge, UK, 2016; e.T23062A46190249. [Google Scholar]

- Dell’Arte, G.L.; Laaksonen, T.; Norrdahl, K.; Korpimäki, E. Variation in the diet composition of a generalist predator, the red fox, in relation to season and density of main prey. Acta Oecol. 2007, 31, 276–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šálek, M.; Drahníková, L.; Tkadlec, E. Changes in home range sizes and population densities of carnivore species along the natural to urban habitat gradient. Mamm. Rev. 2015, 45, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakermans, M.; San Martin, W. Extinction Stories; OER Commons Open Educational Resources: Worcester, MA, USA, 2021; Volume 19. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, H.; Li, F.; Dìaz-Sacco, J.J.; Shi, K. Dietary and temporal partitioning facilitates coexistence of sympatric carnivores in the Everest region. Ecol. Evol. Nov. 2022, 12, e9531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gosselink, T.E.; Van Deelen, T.R.; Warner, R.E.; Joselyn, M.G. Temporal Habitat Partitioning and Spatial Use of Coyotes and Red Foxes in East-Central Illinois. J. Wildl. Manag. 2003, 67, 90–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrov, P.; Popova, E.; Zlatanova, D. Niche Partitioning among the Red Fox Vulpes vulpes (L.), Stone Marten Martes foina (Erxleben) and Pine Marten Martes martes (L.) in Two Mountains in Bulgaria. Acta Zool. Bulgar. 2016, 68, 375–390. [Google Scholar]

- Haswell, P.M.; Jones, K.A.; Kusak, J.; Hayward, M.W. Fear, foraging and olfaction: How mesopredators avoid costly interactions with apex predators. Oecologia 2018, 187, 573–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torretta, E.; Riboldi, L.; Costa, E.; Delfoco, C.; Frignani, E.; Meriggi, A. Niche partitioning between sympatric wild canids: The case of the golden jackal (Canis aureus) and the red fox (Vulpes vulpes) in north-eastern Italy. BMC Ecol. Evol. 2021, 21, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanszki, J.; Hayward, M.W.; Nagyapàti, N. Feeding responses of the golden jackal after reduction of anthropogenic food subsidies. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0208727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Traba, J.; Arrieta, S.; Herranz, J.; Clamagirand, M.C. Red fox (Vulpes vulpes) favour seed dispersal, germination and seedling survival of Mediterranean Hackberry (Celtis australis L.). Acta Oecol. 2006, 30, 39–45. [Google Scholar]

- Traveset, A.; Robertson, A.W.; Rodrìgues-Pérex, J. A review on the role of endozoochory on seed germination. In Seed Dispersal: Theory and Its Application in a Changing World; Dennis, A.J., Schupp, E.W., Green, R.J., Westcott, D.A., Eds.; CAB International: Wallingford, UK, 2007; pp. 78–103. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, H.S.; Cavazos, B.R.; Gawel, A.M.; Karnish, A.; Ray, C.A.; Rose, E.; Thierry, H.; Fricke, E.C. Frugivore gut passage increases seed germination: An updated meta-analysis. bioRxiv 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piscopo, N.; Gentile, L.; Scioli, E.; Eguren, V.G.; Carvajal Urueña, A.M.; García, T.Y.; Alberti, J.P.; Esposito, L. Management models applied to the human-wolf conflict in agro-forestry-pastoral territories of two Italian protected areas and one Spanish game area. Animals 2021, 11, 1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, P.; Furlong, M.; Southern, S.; Harris, S. The potential impact of red fox Vulpes vulpes predation in agricultural landscapes in lowland Britain. Wildlife Biol. 2006, 12, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guadagno, E.; Gallizia, A.; Galosi, L.; Quagliardi, M. Protection of farms from wolf predation: A field approach. Land 2023, 12, 1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://riservacalanchidiatri.it/la-riserva/ (accessed on 22 January 2024).

- Hartová-Nentvichová, M.; Šálek, M.; Červený, J.; Koubek, P. Variation in the diet of the red fox (Vulpes vulpes) in mountain habitats: Effects of altitude and season. Mamm. Biol. 2010, 75, 334–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavallini, P. Variation in the social system of the red fox. Ethol. Ecol. Evol. 1996, 8, 323–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, K.A.; Bhat, B.A.; Ganai, B.A.; Majeed, A. Food habits of the red fox Vulpes vulpes (Mammalia: Carnivora: Canidae) in Dachigam National Park of the Kashmir Himalaya, India. J. Threat. Taxa 2023, 15, 22364–22370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobile, F. Intervista con la Volpe; Editoriale Olimpia: Bologna, Italy, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Petersen, A.; Åkesson, M.; Axner, E.; Ågren, E.; Wikenros, C.; Dalin, A.M. Characteristics of reproductive organs and estimates of reproductive potential in Scandinavian male grey wolves (Canis lupus). Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2021, 226, 106693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kost, C. Chemical communication. In Encyclopedia of Ecology; Jørgensen, S.E., Fath, B.D., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2008; pp. 557–575. [Google Scholar]

- DeVault, T.L.; Rhodes, O.E.; Shivik, J.A. Scavenging by vertebrates: Behavioral, ecological, and evolutionary perspectives on an important energy transfer pathway in terrestrial ecosystems. Oikos 2003, 102, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papageorgiou, N.K.; Sepougaris, A.; Christopoulou, O.G.; Vlachos, C.G.; Petamidis, J.S. Food habits of the red fox in Greece. Acta Theriol. 1988, 33, 313–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Reyes, Z.; Martín-López, B.; Moleón, M.; Mateo-Tomás, P.; Botella, F.; Margalida, A.; Donázar, J.A.; Blanco, G.; Pérez, I.; Sánchez-Zapata, J.A. Farmer perceptions of the ecosystem services provided by scavengers: What, who, and to whom. Conser. Lett. 2018, 11, e12392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapira, O.; Malkinson, D.; Izhaki, I.; Zemah-Shamir, S. Farmers’ perceptions of coexisting with a predator assemblage: Quantification, characterization, and recommendations for human-carnivore conflict mitigation. J. Nat. Conser. 2024, 80, 126644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 | Q8 | Q9 | Q10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | no | yes | Hens | 5 | Night shelter | yes | yes | no | yes | |

| 2 | no | yes | Hens | 4 | Night shelter | yes | yes | no | yes | |

| 3 | yes | yes | Hens | 23 | Night shelter | no | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| 4 | no | yes | Hens, ducks | 50 | Night shelter | yes | yes | no | yes | |

| 5 | no | yes | Chickens, hens | 20 | Night shelter | yes | yes | no | yes | |

| 6 | no | yes | Chickens, hens, rabbits, ducks | 10 | Night shelter | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| 7 | no | yes | Chickens, hens, rabbits, ducks | 20 | Night shelter | yes | yes | no | yes | |

| 8 | yes | yes | Chickens, hens, rabbits | 30 | Night shelter | yes | yes | no | yes | |

| 9 | no | yes | Hens, ducks | 20 | Night shelter | yes | yes | no | yes | |

| 10 | yes | yes | Hens | 15 | Night shelter | yes | yes | no | yes | |

| 11 | no | yes | Hens | 10 | Night shelter | no | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| 12 | no | yes | Hens | 10 | Night shelter | yes | yes | no | yes | |

| 13 | no | yes | Chickens, hens, ducks | 15 | Night shelter | yes | yes | no | yes | |

| 14 | no | yes | Hens | 8 | Night shelter | yes | yes | no | yes | |

| 15 | no | yes | Chickens, hens, rabbits, ducks | 20 | Night shelter | yes | no | no | yes | |

| 16 | no | yes | Chickens, hens, ducks | 20 | Night shelter | yes | yes | no | yes | |

| 17 | no | yes | Hens | 20 | Night shelter | yes | yes | no | yes | |

| 18 | no | yes | Hens | 6 | Night shelter | no | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| 19 | no | yes | Hens | 15 | Night shelter | yes | yes | no | yes | |

| 20 | no | yes | Hens | 30 | Night shelter | yes | yes | no | yes | |

| 21 | no | yes | Rabbits | 20 | Night shelter | no | yes | no | yes | |

| 22 | no | yes | Hens | 10 | Night shelter | yes | yes | no | yes | |

| 23 | no | yes | Hens | 15 | Night shelter | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| 24 | no | yes | Chickens, hens, rabbits | 23 | Night shelter | yes | yes | no | yes | |

| 25 | no | yes | Hens | 15 | Night shelter | yes | yes | no | yes | |

| 26 | no | yes | Hens | 20 | Night shelter | yes | yes | no | yes | |

| 27 | no | yes | Chickens, hens | 30 | Night shelter | yes | yes | no | yes | |

| 28 | no | yes | Hens | 15 | Night shelter | yes | yes | no | yes | |

| 29 | no | yes | Chickens, hens | 10 | Free during the night | yes | yes | no | yes | |

| 30 | no | yes | Hens | 15 | Night shelter | yes | yes | no | yes |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Muzi, H.; Vallesi, A.; Pennacchioni, G.; Trenta, F.; Ferretti, M.; De Ascentiis, A.; Gallizia, A. Spatiotemporal Activity and Farmers’ Perception of the Red Fox in a Regional Reserve of Central Italy: A Case Study. Wild 2025, 2, 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/wild2010001

Muzi H, Vallesi A, Pennacchioni G, Trenta F, Ferretti M, De Ascentiis A, Gallizia A. Spatiotemporal Activity and Farmers’ Perception of the Red Fox in a Regional Reserve of Central Italy: A Case Study. Wild. 2025; 2(1):1. https://doi.org/10.3390/wild2010001

Chicago/Turabian StyleMuzi, Heloise, Adriana Vallesi, Giampaolo Pennacchioni, Francesca Trenta, Matteo Ferretti, Adriano De Ascentiis, and Andrea Gallizia. 2025. "Spatiotemporal Activity and Farmers’ Perception of the Red Fox in a Regional Reserve of Central Italy: A Case Study" Wild 2, no. 1: 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/wild2010001

APA StyleMuzi, H., Vallesi, A., Pennacchioni, G., Trenta, F., Ferretti, M., De Ascentiis, A., & Gallizia, A. (2025). Spatiotemporal Activity and Farmers’ Perception of the Red Fox in a Regional Reserve of Central Italy: A Case Study. Wild, 2(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/wild2010001