2.1. Study Design and Participants

This study was conducted as part of a broader care initiative by the Alzheimer Society Hamm and the Telemedicine Center Hamm. The primary objective was to evaluate the combined impact of Digital Cognitive Stimulation Therapy (DKST) and online hearing training on dementia patients with hearing impairments.

A total of 23 individuals diagnosed with early-stage dementia and hearing impairments were recruited. All participants were equipped with hearing aids; fifteen participants already had hearing aids prior to the study, while eight were newly fitted as part of the intervention. The intervention group comprised 13 women and 10 men, with an average age of 75.4 years (±5.2). The control group included 11 women and 12 men, with an average age of 76.1 years (±6.0). The participants were recruited from local care facilities and the Alzheimer Society Hamm, with 83% of the intervention group living at home and 17% in residential care facilities. Similar distributions were observed in the control group.

Participants were eligible if they had a clinical diagnosis of dementia and were capable of providing informed consent or had a legally authorized representative. The exclusion criteria included severe visual or motor impairments that could hinder tablet use. Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

The control group, with participants drawn from three geriatric day-care facilities, received standard dementia care without additional interventions. This group served as a baseline for comparison. A non-active control group was chosen due to resource constraints and ethical considerations, ensuring that all participants received at least the usual standard of care without introducing unnecessary burdens or inequalities. The demographic characteristics of the participants are shown in

Table 1.

2.3. Structure of Intervention Sessions

Each session followed a structured format tailored to the individual participants:

Orientation (15 min):

The participant was personally welcomed by name and introduced to the session. A brief discussion of the current date, location, and season was held. A current newspaper headline was introduced and discussed to engage the participant. Light activities, such as passing a small object like a stress ball, were conducted to help the participant relax and prepare for the session.

Main Activities (30 min):

Five exercises from the DKST and hearing training modules were performed in a rotating fashion, ensuring variety and engagement. The exercises were tailored to the participant’s individual abilities, with task difficulty dynamically adjusted by the platform.

Conclusion (15 min):

The session’s activities were summarized for the participant. Feedback was collected from the participant, and the next session’s agenda was briefly discussed. The session ended with a friendly farewell and encouragement for the next session.

2.4. Integration of Co-Therapists

A critical element of DKST is the role of co-therapists, who assist dementia patients during the digital exercises. Dementia patients are rarely able to engage in digital cognitive exercises independently due to limitations in comprehension, motivation, or coordination. For this reason, trained co-therapists—either family members or volunteers—play an essential role in supporting the patients throughout the process. They are present to help guide the patients through the tasks, explain instructions, and ensure that the exercises are completed correctly. This not only helps patients to engage more effectively with the tasks, but also provides an element of social interaction, which has been shown to further enhance the therapeutic benefits.

The activation program, designed by the Telemedicine Center Hamm, outlines two main routes for the involvement of co-therapists in DKST, each adapted to different patient and caregiver scenarios.

Route 1: External co-therapists (not related to the patient):

In this model, the co-therapists are not family members of the patient but are trained volunteers or external caregivers. These co-therapists receive online guidance from certified therapists and meet the patients in person to assist them with their digital exercises. The therapists, who oversee the intervention remotely, ensure that the co-therapists are equipped with the necessary skills and knowledge to provide effective support.

Figure 4 illustrates Option 1 of the activation program, which was developed for co-therapists who are not related to the patient.

Route 2: Family members as co-therapists:

In situations where a family member is available and willing to take on the role of a co-therapist, this person is trained to work closely with the patient. In this model, both family members and external co-therapists can collaborate, with family members taking on a more personal role in daily support. The digital platform allows therapists to continue providing remote guidance, while the family member ensures the continuity of and engagement in the exercises.

Figure 5 illustrates Option 2 of the activation program, designed for relatives acting as co-therapists.

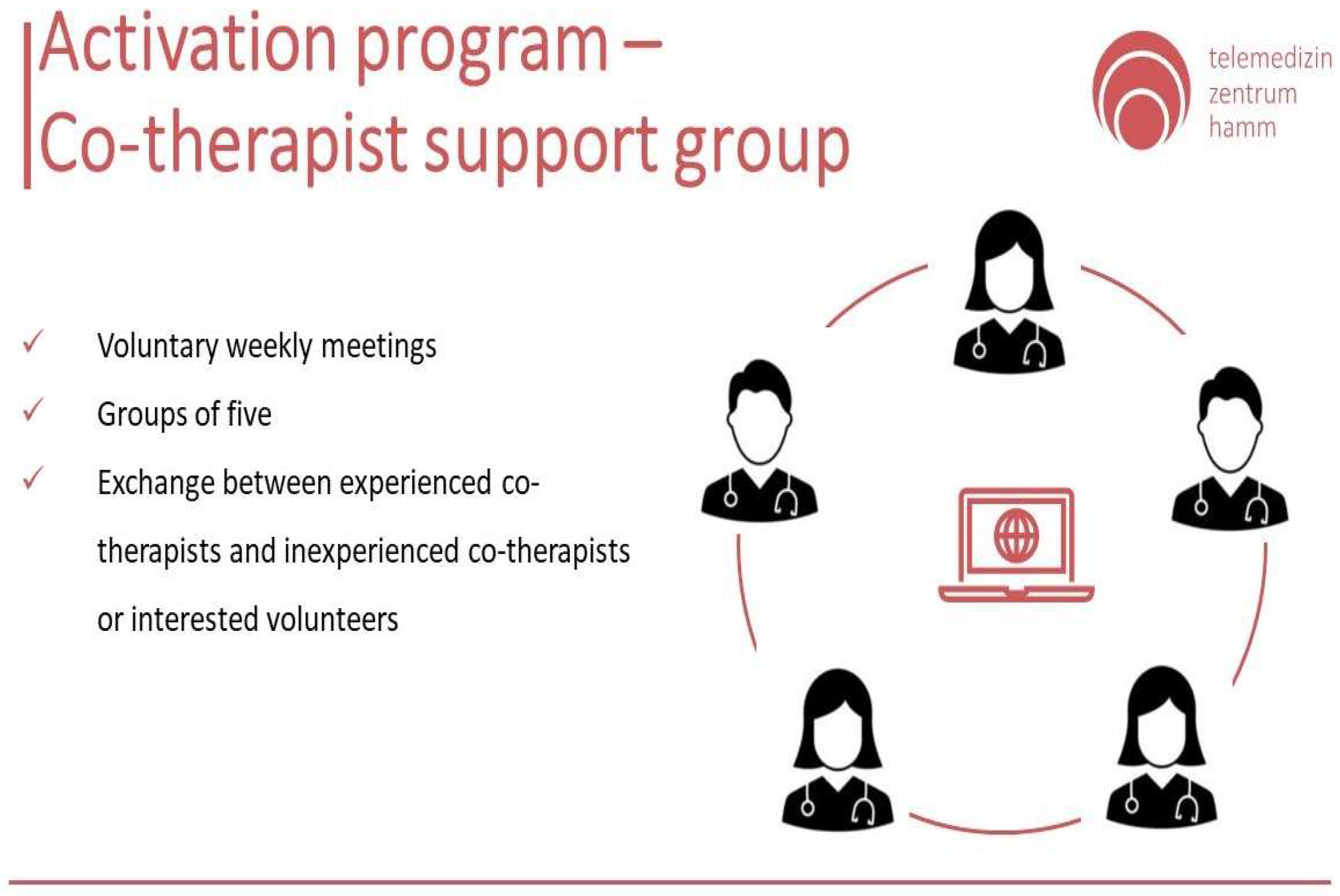

In both routes, the co-therapists meet regularly in support groups, where they can share experiences, seek advice, and receive further training. Such meetings foster collaboration and continuous learning, which are essential for ensuring high-quality care. These groups provide a vital exchange between experienced co-therapists and newcomers or volunteers interested in assisting dementia patients (

Figure 6). Such meetings foster collaboration and continuous learning, which are essential for ensuring high-quality care.

A critical component of this study is the structured qualification program designed for co-therapists who assist dementia patients during the Digital Cognitive Stimulation Therapy (DKST). This program ensures that co-therapists are well equipped to support both the cognitive and auditory needs of dementia patients, particularly in remote or telemedicine settings. The qualification program is divided into 50 learning units, delivered through a combination of webinars and e-learning modules (

Figure 7).

The structure of the course is as follows:

Telemedicine Course on Patient Care (10 units): The first webinar, consisting of 10 learning units, focuses on the fundamentals of telemedicine, particularly in the context of patient care. This webinar equips co-therapists with the skills needed to effectively manage dementia patients remotely, addressing the challenges of virtual care, patient engagement, and ensuring compliance with care protocols in a telehealth setting.

Virtual Cognitive Stimulation Therapy (two units): In the second webinar, co-therapists receive training in Virtual Cognitive Stimulation Therapy (CST). The two units in this module cover how to deliver cognitive exercises via digital platforms, ensuring that co-therapists can facilitate the DKST program effectively. The training emphasizes how to adapt cognitive exercises to the patient’s specific abilities, enabling dynamic and engaging therapeutic sessions.

Hearing, Hearing Aids, and Audio Therapy (six units): Given the frequent comorbidity of hearing loss with dementia, the third webinar focuses on auditory rehabilitation. Across six learning units, this module covers the basics of hearing loss, the use of hearing aids, and techniques in audio therapy. Co-therapists learn how to integrate hearing training into the cognitive stimulation exercises, enhancing the efficacy of the therapy for patients with hearing impairments.

Edumentia: Dementia Care Training (24 units): One of the most comprehensive parts of the qualification is the Edumentia e-learning module, which spans 24 units. This module delves into the specifics of dementia care, covering topics such as the progression of dementia, communication strategies, behavioral management, and the psychosocial aspects of caregiving. This in-depth training ensures that co-therapists have a solid understanding of the disease and its impacts, allowing them to provide personalized and empathetic care.

Emergency Management in Patient Care (eight units): The final module comprises eight units on emergency management in patient care. Co-therapists are trained to recognize and respond to potential emergencies that may arise during therapy sessions. This module ensures that co-therapists are prepared to handle crises and maintain patient safety, especially in remote care scenarios where immediate medical assistance may not be available.

This qualification program plays a crucial role in the success of this study by ensuring that co-therapists are not only well versed in the principles of cognitive and auditory therapy but also prepared to deliver these interventions in a virtual setting. The training equips them with the necessary skills to navigate the challenges of telemedicine, digital therapy platforms, and the specific needs of dementia patients with hearing impairments. The comprehensive structure of the program ensures that co-therapists are able to support patients through personalized, adaptive therapies that integrate cognitive stimulation and hearing training, thereby maximizing the therapeutic outcomes of the DKST intervention.

2.8. Assessment Instruments for Cognitive and Hearing Outcomes in Dementia Care

In this study, the co-therapists used several validated questionnaires to assess the outcomes of the intervention, ensuring that the tools were grounded in well-established research and capable of capturing the desired measures. The three primary instruments were the Quality of Life (QoL) Questionnaire, the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), and the Abbreviated Profile of Hearing Aid Benefit (APHAB). Each of these instruments is commonly used in clinical and research settings and offers insights into patients’ cognitive, sensory, and overall well-being.

2.8.1. Quality of Life (QoL) Questionnaire

The primary outcome measure of this study was the improvement in the patients’ quality of life, evaluated using the Quality of Life (QoL) Questionnaire. This tool examines various dimensions, including physical health, psychological well-being, social relationships, and functional abilities. It has been shown to be a reliable instrument in dementia research, particularly for assessing how interventions impact overall well-being beyond cognitive measures. While Cognitive Stimulation Therapy has traditionally been linked to improvements in cognitive domains, the inclusion of QoL allows for a broader understanding of the intervention’s effect on the patient’s daily life and personal well-being [

4,

9,

10].

2.8.2. Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE)

Cognitive function was assessed using the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), a widely recognized tool in dementia care. The MMSE evaluates several cognitive domains, such as orientation, memory, attention, and language, providing a quantitative measure of cognitive impairment. While it offers a relatively quick assessment, it has been widely used to track cognitive changes over time, making it suitable for assessing the impact of cognitive therapies like DKST. Studies have demonstrated that the MMSE can provide consistent results in both clinical practice and research settings, especially when used in longitudinal assessments of dementia patients [

11,

12,

13].

2.8.3. Abbreviated Profile of Hearing Aid Benefit (APHAB) Questionnaire

Hearing-related outcomes were evaluated using the Abbreviated Profile of Hearing Aid Benefit (APHAB). This tool measures the benefits provided by hearing aids in various listening environments and assesses hearing-related quality of life. Since many dementia patients experience hearing loss, which can exacerbate cognitive difficulties, the APHAB is valuable for understanding how auditory interventions, like hearing training, contribute to the therapy’s overall effectiveness. It has been used in multiple studies to evaluate the intersection of hearing and cognitive health [

6,

14,

15].

These tools were selected not only for their established use in clinical and research settings but also because they aligned with this study’s goals. The QoL, MMSE, and APHAB allowed us to assess a broad range of outcomes, from cognitive improvements to sensory and emotional well-being. These questionnaires provided a structured way to capture the multifaceted effects of the intervention, helping to ensure that the study’s outcomes could be evaluated on a sound scientific basis. While these instruments have been widely accepted, we acknowledge that no single tool captures all dimensions of patient care, and the results should always be interpreted in the broader context of dementia management.

2.8.4. Evaluation of Outcome Measures: A Multidimensional Approach

The combination of the MMSE (Mini-Mental State Examination), APHAB (Abbreviated Profile of Hearing Aid Benefit), and the Quality of Life (QoL) Questionnaire was deliberately chosen to capture the multidimensional effects of the intervention. While the MMSE primarily serves to identify the target group and establish the cognitive baseline of participants, the APHAB complements this cognitive dimension by evaluating hearing-related quality of life, particularly in various acoustic contexts. However, both instruments address specific aspects and, on their own, would not sufficiently capture the overarching goal of this study, which is to improve the quality of life of people with dementia.

The QoL Questionnaire, therefore, represents an essential addition, as it goes beyond cognitive and auditory measures to provide a more holistic view of quality of life. This instrument considers key dimensions such as physical health, psychological well-being, social relationships, and functional abilities. It is an established and reliable tool in dementia research, particularly suited to assessing the impact of interventions on patients’ overall well-being. Incorporating the QoL Questionnaire enables a differentiated analysis of how the intervention improves not only cognitive or sensory aspects but also daily life and participants’ subjective well-being.

The combination of these three instruments allows for a comprehensive evaluation of the intervention. The MMSE provides a baseline for cognitive status, the APHAB assesses hearing-related quality of life, and the QoL Questionnaire broadens the perspective to encompass the entire spectrum of quality of life. Together, they enable the analysis of the intervention’s effects on both functional and psychosocial levels.

Nevertheless, additional instruments, such as questionnaires to assess depression and anxiety (e.g., Geriatric Depression Scale or State-Trait Anxiety Inventory), could further enhance the analysis of participants’ psychosocial well-being in future studies. These additions could help to identify the potential indirect effects of the intervention, such as reductions in depressive symptoms or anxiety. Similarly, the use of more cognitively specific tests, such as the ADAS-Cog (Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale-Cognitive Subscale), could provide more detailed insights into the cognitive impact of the intervention.

In summary, the combination of the MMSE, APHAB, and QoL Questionnaire already allows for a robust and differentiated analysis of the intervention. However, integrating additional instruments in future studies could capture the cognitive, psychosocial, and functional outcomes more comprehensively, laying the groundwork for further innovations in the treatment of people with dementia.