Fidelity Assessment Tool for a Dementia Carers’ Group-Psychotherapy Intervention

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Design and Development of the RCCP-FAT

2.2. Development of Rater Training Materials

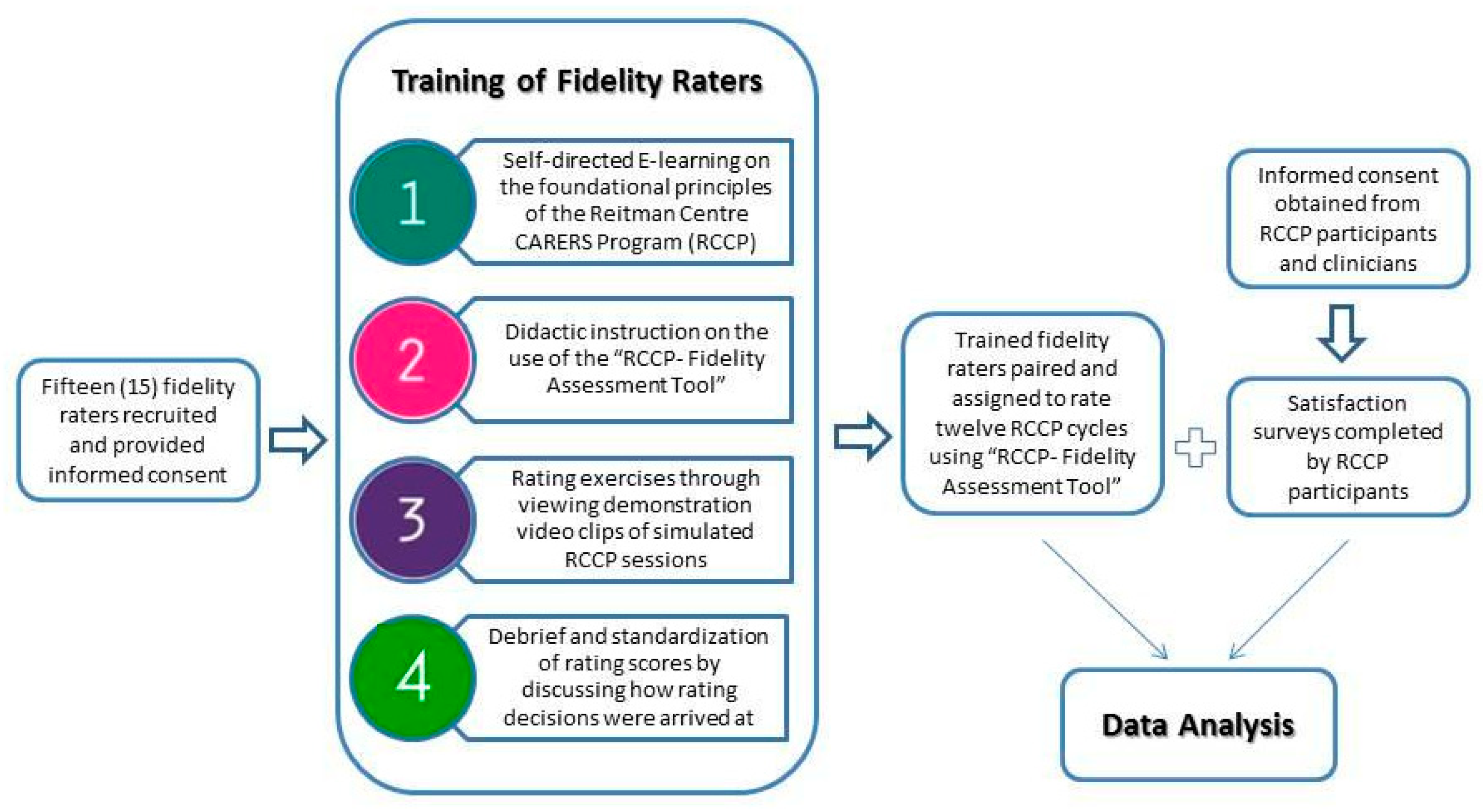

2.3. Recruitment and Training Volunteer Raters and Research Ethics Clearance

- Discussion and questions regarding the RCCP and self-directed e-learning modules;

- Systematic review of components of the RCCP-FAT;

- Practice in use of the RCCP-FAT using standardized video clips;

- Discussion of scored items, item consensus, and scoring challenges;

- Practice in use of the RCCP-FAT using standardized video clips; and

- Discussion of scored items, item consensus (or lack thereof), and rationale for scoring differences.

2.4. Data Collection

2.5. Data Analysis

2.5.1. Rater Agreement of RCCP-FAT

2.5.2. Correlation Between Itemized and Global Scores for Each Fidelity Assessment Component

2.5.3. Correlation Between Fidelity Ratings and RCCP Participants’ Satisfaction

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bellg, A.J.; Borrelli, B.; Resnick, B.; Hecht, J.; Minicucci, D.S.; Ory, M.; Ogedegbe, G.; Orwig, D.; Ernst, D.; Czajkowski, S.; et al. Enhancing Treatment Fidelity in Health Behaviour Change Studies: Best Practices and Recommendations for the NIH Behaviour Change Consortium. Health Psychol. 2004, 23, 443–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dumas, J.E.; Lynch, A.M.; Laughlin, J.E.; Phillips, S.E.; Prinz, R.J. Promoting Intervention Fidelity. Conceptual Issues, Methods, and Preliminary Results from the EARLY ALLIANCE Prevention Trial. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2001, 20, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perepletchikova, F.; Kazdin, A.E. Treatment Integrity and Therapeutic Change: Issues and Research Recommendations. Clin. Psychol. 2005, 12, 365–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santacroce, S.J.; Maccarelli, L.M.; Grey, M. Intervention Fidelity. Clin. Nurs. Res. 2004, 53, 63–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stein, K.F.; Sargent, J.T.; Rafaels, N. Intervention Research: Establishing Fidelity of the Independent Variable in Nursing Clinical Trials. Adv. Nurs. Res. 2007, 56, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hepner, K.A.; Howard, S.; Paddock, S.M.; Hunter, S.B.; Osilla, K.C.; Watkins, K.E. A Fidelity Coding Guide for a Group Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Depression; RAND Corporation: Santa Monica, CA, USA, 2011; Available online: https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/technical_reports/2011/RAND_TR980.pdf (accessed on 12 January 2017).

- Breitenstein, S.L.; Robbins, L.J.; Muennich Cowell, J.M. Attention to Fidelity: Why Is It Important. J. Sch. Nurs. 2012, 28, 407–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenaway, D.; Halverson, P.; Sotnikov, S.; Tilson, H.; Corso, L.; Millington, W. Public Health Systems Research: Setting a National Agenda. Am. J. Public Health 2006, 96, 410–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.K.; Happ, M.B.; Sandelowski, M. Development of a Tool to Assess Fidelity to a Psycho-Educational Intervention. J. Adv. Nurs. 2010, 66, 673–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teague, G.B.; Mueser, K.T.; Rapp, C.A. Advances in Fidelity Measurement for Mental Health Services Research. Psychiat. Serv. 2012, 63, 765–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardito, R.B.; Rabellino, D. Therapeutic Alliance and Outcome of Psychotherapy: Historical Excursus, Measurements, and Prospects for Research. Front. Psychol. 2011, 18, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogue, A.; Henderson, C.E.; Dauber, S.; Barajas, P.C.; Fried, A.; Liddle, H.A. Treatment Adherence, Competence, and Outcome in Individual and Family Therapy for Adolescent Behavior Problems. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2008, 76, 544–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheridan, S.M.; Swanger-Gagne, M.; Welch, G.W.; Kwon, K.; Garbacz, S.A. Fidelity Measurement in Consultation: Psychometric Issues and Preliminary Examination. Sch. Psych. Rev. 2009, 38, 476–495. [Google Scholar]

- Mars, T.; Ellard, D.; Carnes, D.; Homer, K.; Underwood, M.; Taylor, S.J.C. Fidelity in Complex Behaviour Change Interventions: A Standardized Approach to Evaluate Intervention Integrity. BMJ Open 2013, 11, e003555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schoenwald, S.K.; Garland, A.F.; Chapman, J.E.; Frazier, S.L.; Sheidow, A.J.; Southam-Gerow, M.A. Toward the Effective and Efficient Measurement of Implementation Fidelity. Adm. Policy Ment. Health 2011, 38, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobson, D.; Cook, T.J. Avoiding type III Error in Program Evaluation: Results from a Field Experiment. Eval. Program. Plann. 1980, 3, 269–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margison, F.R.; McGrath, G.; Barkham, M.; Clark, J.M.; Audin, K.; Connell, J.; Evans, C. Measurement and Psychotherapy. Evidence-based Practice and Practice-Based Evidence. Br. J. Psychiatry 2000, 177, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadavoy, J.; Sajedinejad, S.; Chiu, M. A quasi-experimental study of the effectiveness of the Reitman Centre CARERS group intervention on family caregivers of persons with dementia. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2021, 36, 811–821. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, W.; Yanos, P.T.; Gottlieb, J.D.; Marcello Duva, S.M.; Silverstein, S.M.; Xie, H.; Rosenberg, S.D.; Mueser, K.T. Using Fidelity Assessments to Train Frontline Clinicians in the Delivery of Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for PTSD in Persons with Serious Mental Illness. Psychiatr. Serv. 2012, 63, 785–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- North Carolina Evidence Based Practices Centre. Family Psychoeducation Fidelity Scale. Updated 2002. Available online: https://www.ncebpcenter.org/assets/FPE_Protocol.pdf (accessed on 17 November 2024).

- Hepner, K.A.; Hunter, S.B.; Paddock, S.M.; Zhou, A.; Watkins, K.E. Training Addiction Counselors to Implement CBT for Depression. Adm. Policy Ment. Health 2011, 38, 313–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richey, R.; Klein, J. Developmental Research Methods: Creating Knowledge from Instructional Design and Development Practice. J. Comput. High. Educ. 2005, 16, 23–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imel, S. Using Adult Learning Principles in Adult Basic and Literacy Education. Updated 1998. Available online: https://sswm.info/sites/default/files/reference_attachments/SUSAN%201998%20Using%20Adult%20Learning%20Principles%20in%20Adult%20Basic%20and%20Literacy%20Education%20Columbus.pdf (accessed on 17 November 2024).

- Yalom, I.D.; Leszcz, M. The Theory and Practice of Group Psychotherapy; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hallgren, K.A. Computing Inter-Rater Reliability for Observational Data: An Overview and Tutorial. Tutor. Quant. Methods Psychol. 2012, 8, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viera, A.J.; Garrett, J.M. Understanding Interobserver Agreement: The Kappa Statistic. Fam. Med. 2005, 37, 360–363. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cook, D.A.; Beckman, T.J. Current Concepts in Validity and Reliability for Psychometric Instruments: Theory and Application. Am. J. Med. 2006, 119, 166.e7–166.e16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, K.M.; Nich, C.; Sifry, R.L.; Nuro, K.F.; Frankforter, T.L.; Ball, S.A.; Fenton, L.; Rounsaville, B.J. A General System for Evaluating Therapist Adherence and Competence in Psychotherapy Research in the Addictions. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2000, 57, 225–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breitenstein, S.M.; Gross, D.; Gravey, C.; Hill, C.; Fogg, L.; Resnick, B. Implementation Fidelity in Community-Based Interventions. Res Nurs. Health 2010, 33, 164–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeates, P.; O’Neill, P.; Mann, K.; Eva, K. ‘You’re Certainly Relatively Competent’: Assessor Biases due to Recent Experiences. Med. Educ. 2013, 47, 910–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ginsburg, L.R.; Tregunno, D.; Norton, P.G.; Smee, S.; de Vries, I.; Sebok, S.S.; VanDenKerkhof, E.G.; Luctkar-Flude, M.; Medves, J. Development and Testing of an Objective Structured Clinical Exam (OSCE) to Assess Socio-Cultural Dimensions of Patient Safety Competency. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2015, 24, 188–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Neilipovitz, D.; Cardinal, P.; Chiu, M. A Comparison of Global Rating Scale and Checklist Scores in the Validation of an Evaluation Tool to Assess Performance in the Resuscitation of Critically Ill Patients During Simulated Emergencies (Abbreviated as “CRM Simulator Study IB”). Simul. Healthc. 2009, 4, 6–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuwirth, L.W.; van der Vleuten, C.P.M. Programmatic Assessment: From Assessment of Learning to Assessment for Learning. Med. Teach. 2011, 33, 478–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| RCCP Component | Theoretical Foundation | Component Description |

|---|---|---|

| Structured Group Sessions 3 items | Focused Group Therapy Adult Education | The developed structure of the RCCP model must be followed during a session, and a clear agenda, goals, and expectations must be established for each session. |

| Dementia Education 3 items | Adult Education [23] | Evaluates how effectively group leaders provide basic understanding of dementia based on specific expressed experiences, concerns, and misconceptions. |

| Problem-Solving Techniques (PST) 5 items | Adapted from CBT and PST Adult Education [23] | A structured and systematic multi-step technique to identify specific problems and develop targeted strategies to manage them. Participants choose which problem is most pressing to them, and the process is recorded visually. |

| Therapeutic Simulation 8 items | Simulation Methodology Adult Education [23] | Re-enactments of communication, relational, or behavioural challenges faced by family care givers for skills building. Includes experiential learning and immediate and specific feedback. |

| Vertical Cohesion 3 items | Group Therapy [24] | Quality of cohesion between the group leader and each carer and between the group leader and the group (includes warmth, genuineness, empathy, and engagement). |

| Horizontal Cohesion 7 items | Group Therapy | Attraction of the group to its members, analogous to therapeutic alliance between the group leader and the group members. |

| Overall Global Rating 1 item | All (Group Therapy, Adult Education, CBT, and PST) | Overall assessment of performance across all major RCCP components. |

| Tool Construct | Value | 95% Confidence Interval | Asymp. Std. Error | Approx. Sig. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Structured Group Sessions | Measure of Agreement (Kappa) | 0.352 | 0.2042–0.499 | 0.077 | 0.000 |

| N of Valid Cases | 102 | ||||

| Dementia Education | Measure of Agreement (Kappa) | 0.315 | 0.1687–0.4617 | 0.072 | 0.000 |

| N of Valid Cases | 97 | ||||

| Problem-Solving Therapy | Measure of Agreement (Kappa) | 0.336 | 0.1663–0.5065 | 0.087 | 0.000 |

| N of Valid Cases | 66 | ||||

| Simulation | Measure of Agreement (Kappa) | 0.370 | 0.2157–0.5247 | 0.078 | 0.000 |

| N of Valid Cases | 88 | ||||

| Vertical Cohesion | Measure of Agreement (Kappa) | 0.453 | 0.3241–0.5811 | 0.064 | 0.000 |

| N of Valid Cases | 127 | ||||

| Horizontal Cohesion | Measure of Agreement (Kappa) | 0.195 | 0.1049–0.2853 | 0.046 | 0.000 |

| N of Valid Cases | 258 | ||||

| N | Correlation Coefficient | Sig. (2-Tailed) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Correlation between itemized and global scoring of fidelity component measures: | |||

| Group Structure | 21 | 0.833 * | 0.000 |

| Dementia Education | 22 | 0.919 * | 0.000 |

| Problem-Solving Therapy | 17 | 0.924 * | 0.000 |

| Therapeutic Simulation | 18 | 0.929 * | 0.000 |

| Vertical Cohesion | 60 | 0.923 * | 0.000 |

| Horizontal Cohesion | 59 | 0.892 * | 0.000 |

| Correlation between RCCP-FAT average global scores and corresponding participant satisfaction survey scores: | |||

| Dementia Education | 36 | 0.185 | 0.280 |

| Problem-Solving Therapy | 36 | −0.197 | 0.250 |

| Simulation | 34 | 0.626 * | 0.000 |

| Average Overall Global Score | 36 | 0.298 | 0.077 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chiu, M.; Nelles, L.J.; Wesson, V.; Lawson, A.; Sadavoy, J. Fidelity Assessment Tool for a Dementia Carers’ Group-Psychotherapy Intervention. J. Dement. Alzheimer's Dis. 2025, 2, 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/jdad2010001

Chiu M, Nelles LJ, Wesson V, Lawson A, Sadavoy J. Fidelity Assessment Tool for a Dementia Carers’ Group-Psychotherapy Intervention. Journal of Dementia and Alzheimer's Disease. 2025; 2(1):1. https://doi.org/10.3390/jdad2010001

Chicago/Turabian StyleChiu, Mary, Laura J. Nelles, Virginia Wesson, Andrea Lawson, and Joel Sadavoy. 2025. "Fidelity Assessment Tool for a Dementia Carers’ Group-Psychotherapy Intervention" Journal of Dementia and Alzheimer's Disease 2, no. 1: 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/jdad2010001

APA StyleChiu, M., Nelles, L. J., Wesson, V., Lawson, A., & Sadavoy, J. (2025). Fidelity Assessment Tool for a Dementia Carers’ Group-Psychotherapy Intervention. Journal of Dementia and Alzheimer's Disease, 2(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/jdad2010001