An Analysis of In-Migration Patterns for California: A Two-Way Fixed Effects Approach Utilizing a Pooled Sample

Abstract

1. Introduction

Background

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Approach

2.2. Theoretical Approach: Extension of Spatial Migration Framework

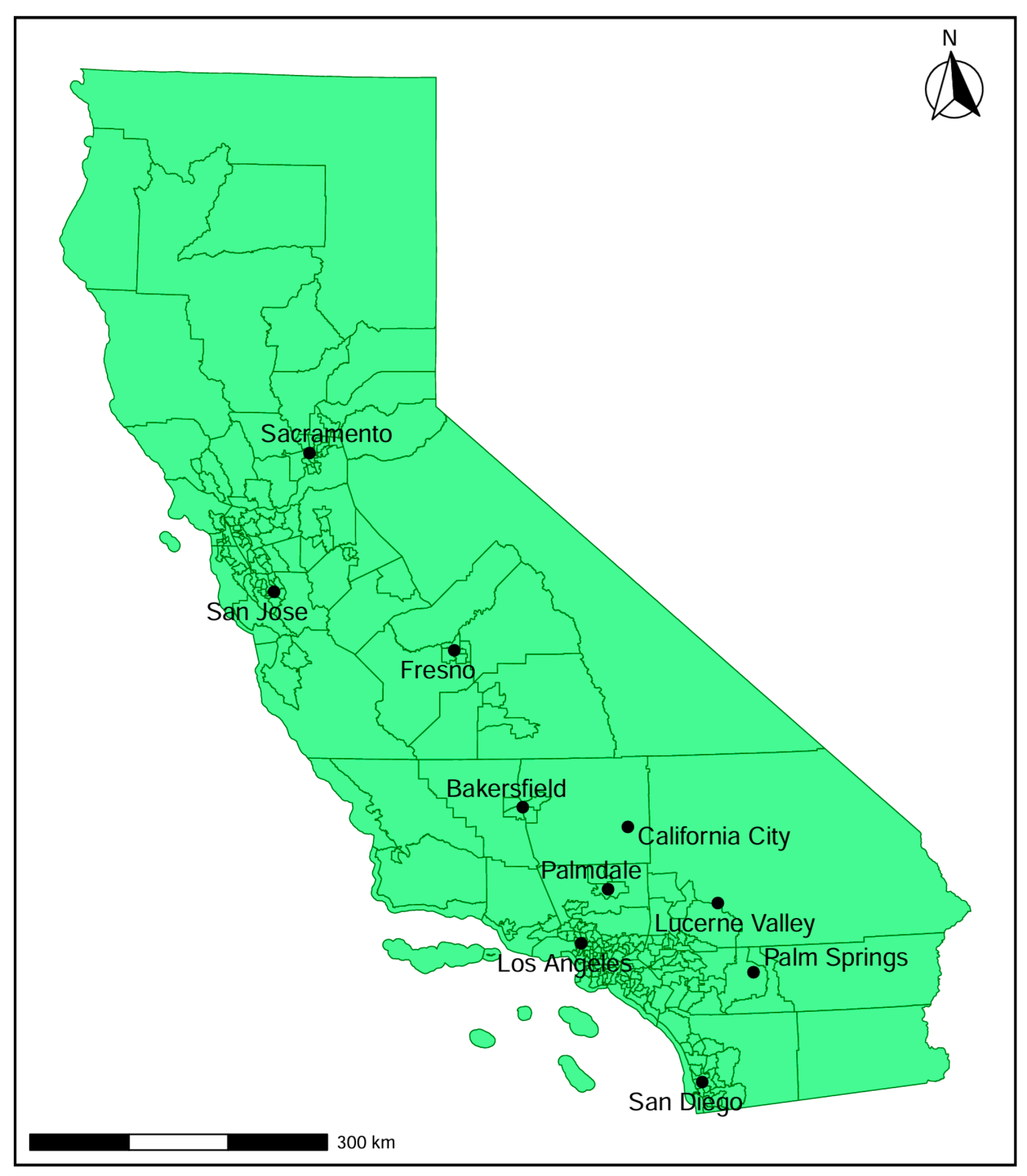

2.3. Study Population

2.4. Measures: Dependent Variable

2.5. Independent Variables

2.6. Estimation Strategy

2.7. Specification Tests

3. Results

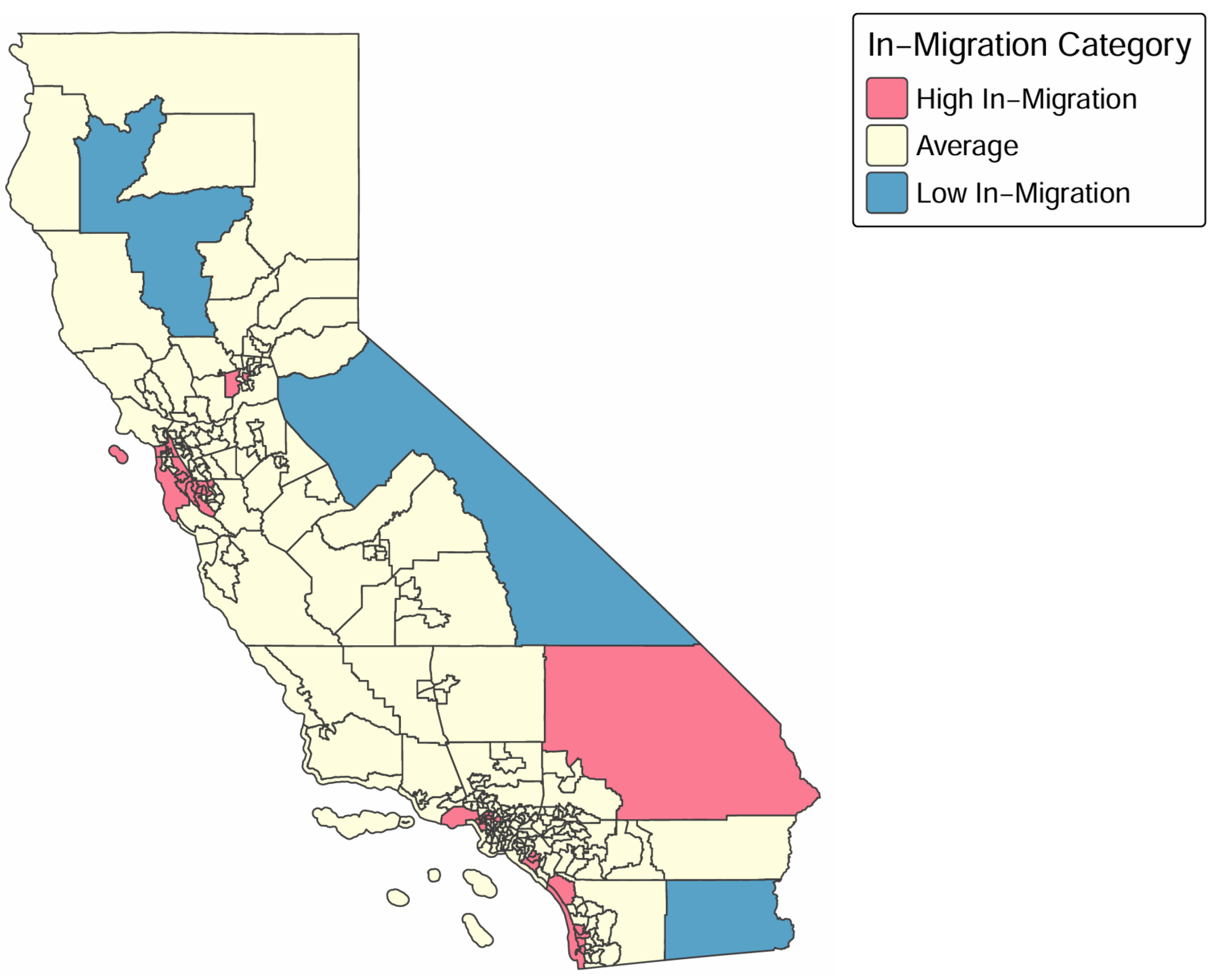

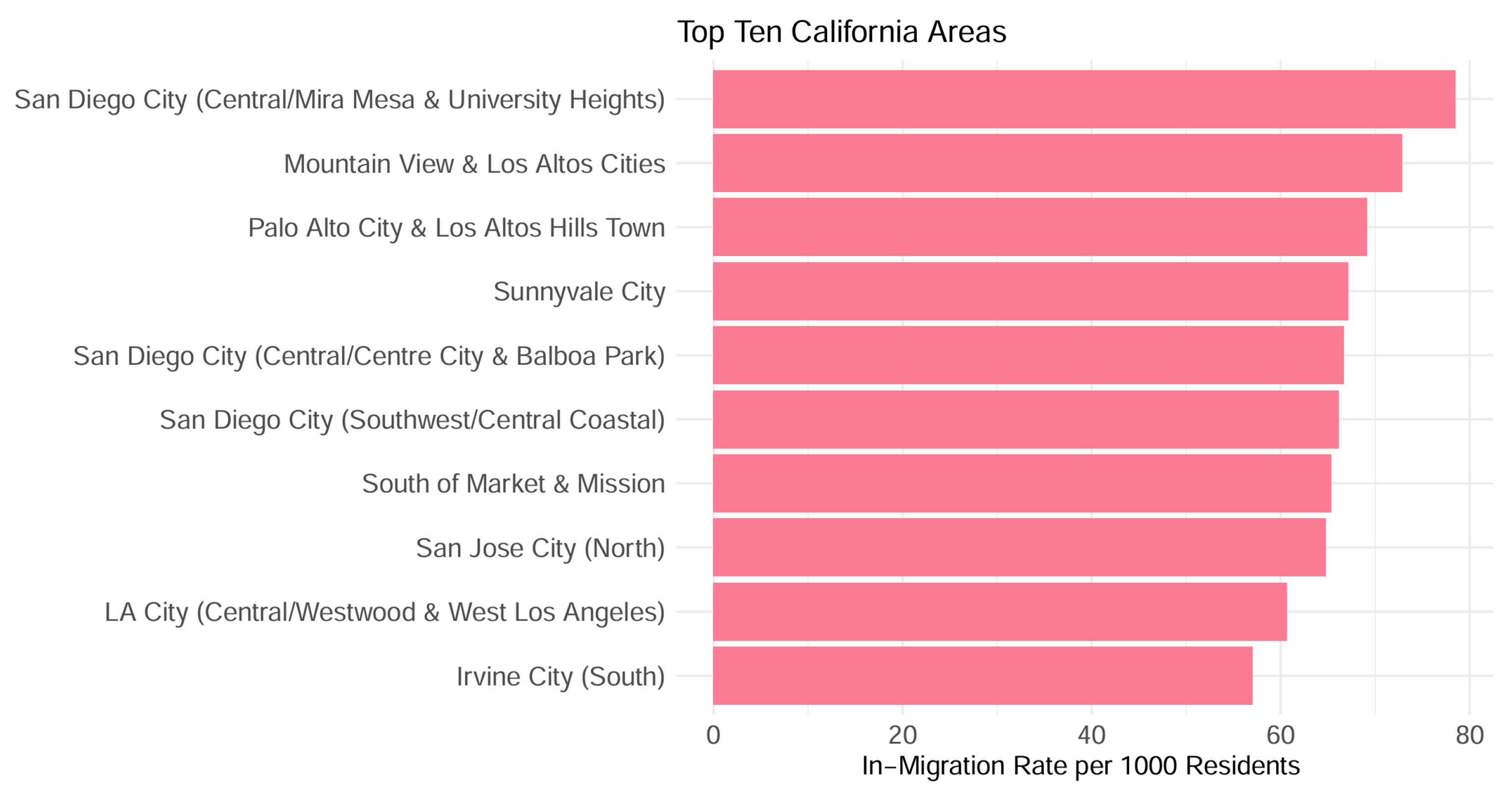

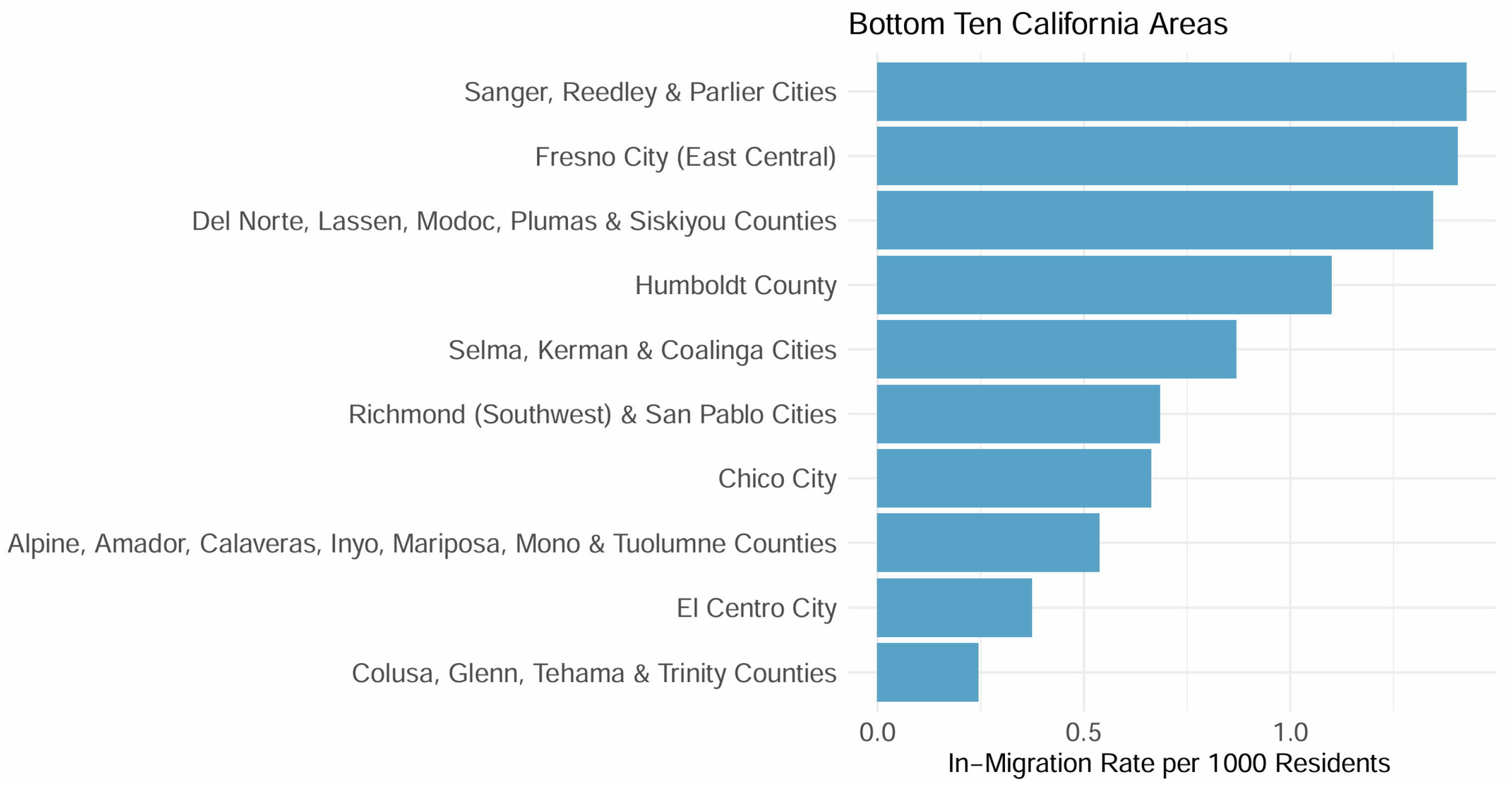

3.1. Descriptive Statistics and Maps

3.2. FE Results

3.3. Demographic Composition

3.4. Economic Indicators

3.5. Housing Characteristics and Temporal Effects

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Coulter, R.; Ham, M.V.; Findlay, A.M. Re-thinking residential mobility: Linking lives through time and space. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2016, 40, 352–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molloy, R.; Smith, C. U.S. Internal Migration: Recent Patterns and Outstanding Puzzles; Federal Reserve Board of Governors: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Morefield, P.E.; Leslie, T.F. County-to-county migration modeling in the United States: The effects of data source and model selection. J. Geogr. Syst. 2025, 27, 455–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tjaden, J. Measuring migration 2.0: A review of digital data sources. Comp. Migr. Stud. 2021, 9, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Census Bureau. Understanding and Using the American Community Survey Public Use Microdata Sample Files: What Data Users Need to Know; U.S. Government Printing Office: Washington, DC, USA, 2021.

- Johnson, H.; McGhee, E. Who’s Leaving California—And Who’s Moving In? Public Policy Institute of California: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2025; Available online: https://www.ppic.org/blog/whos-leaving-california-and-whos-moving-in/ (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Holmes, N.; White, E. Pandemic Patterns: California Is Seeing Fewer Entrances and More Exits, 2021. California Policy Lab. Available online: https://www.capolicylab.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/Pandemic-Patterns.-California-is-Seeing-Fewer-Entrances-and-More-Exits-April-2022-update.pdf (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Gunderson, R.; Sorenson, D. An examination of domestic migration from California counties. J. Reg. Anal. Policy 2010, 40, 34–52. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. State-to-State Migration Flows. 2025. Available online: https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/geographic-mobility/state-to-state-migration.html (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Governor of California. California’s Population Increases Again. 2025. Available online: https://www.gov.ca.gov/2025/05/01/californias-population-increases-again/ (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Sklair, L. Globalization and the Corporations: The Case of the California Fortune 500. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 1998, 22, 195–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svart, L.M. Environmental preference migration: A review. Geogr. Rev. 1976, 66, 314–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoyama, Y.; Powell, W.W.; Saxenian, A.; Scott, A.J.; Storper, M.; Kemeny, T.; Makarem, N.; Osman, T. The rise and fall of urban economies: Lessons from San Francisco and Los Angeles. AAG Rev. Books 2017, 5, 146–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goutsmedt, A. From stagflation to the Great Inflation: Explaining the US economy of the 1970s. Rev. D’économie Polit. 2021, 131, 557–582. [Google Scholar]

- Leslie, S.W.; Kargon, R.H. Electronics and the geography of innovation in post–war America. Hist. Technol. Int. J. 1994, 11, 217–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storper, M.; Kemeny, T.; Makarem, N.; Osman, T. The Rise and Fall of Urban Economies: Lessons from San Francisco and Los Angeles; Series Innovation and Technology in The World Economy; Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Raettig, T.L.; Elmer, D.M.; Christensen, H.H. Atlas of Social and Economic Conditions and Change in Southern California; Gen. Tech. Rep. PNW-GTR-516; US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station: Portland, OR, USA, 2001.

- Southern California Association of Governments. SoCal to Experience Strong Economic Growth into 2024. Available online: https://scag.ca.gov/news/socal-experience-strong-economic-growth-2024 (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Fernandez, E. California dreamers: A rude awakening. San Francisco Examiner. Newspapers.com, 30 July 1989; pp. 1, 14. Available online: https://www.newspapers.com/article/the-san-francisco-examiner/157122965/ (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Gabriel, S.; Mattey, J.P.; Wascher, W.L. House Price Differentials and Dynamics: Evidence from the Los Angeles and San Francisco Metropolitan Areas. Econ. Rev. 1999, 3–22. [Google Scholar]

- Gabriel, S.A.; Mattey, J.P. The Slowing Exodus from California; Economic Letter No. 96-12; Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1996; Available online: https://www.frbsf.org/research-and-insights/publications/economic-letter/1996/12/the-slowing-exodus-from-california/ (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Nussbaum, P. Lifestyle in Southern California spurs exodus. Newspapers.com, 13 August 1989; pp. A1, A4. Available online: https://www.newspapers.com/article/honolulu-star-advertiser/157123022/ (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Frey, W.H. The Great American Migration Slowdown: Regional and Metropolitan Dimensions; Brookings Institution: Washington, DC, USA, 2009; Available online: https://www.brookings.edu/research/the-great-american-migration-slowdown/ (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Gabriel, S.; Freyd, B.; Brand, J.; Fultz, N.; Tzen, M. Recent Trends in California Migration: Evidence from the American Community Survey, 2005–2019; UCLA Ziman Center for Real Estate: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2021; Available online: https://www.universityofcalifornia.edu/sites/default/files/ucla-california-migration-report.pdf (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Johnson, H.P.; Lovelady, R. Migration Between California and Other States: 1985–1994; California Research Bureau: Sacramento, CA, USA, 1995.

- Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research. California’s Population Drain. 2023. Available online: https://siepr.stanford.edu/publications/policy-brief/californias-population-drain (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Grimes, K. California Exodus: Golden State Tops US Moving Migration Report. California Globe, 10 December 2024. Available online: https://californiaglobe.com/articles/california-exodus-golden-state-tops-us-moving-migration-report/ (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- California’s Demographic Landscape: Who’s Coming and Going? GV Wire, 7 March 2025. Available online: https://gvwire.com/2025/03/07/californias-demographic-landscape-whos-coming-and-going/ (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- California Department of Finance, CDOF. 2025–26 Enactment Budget Summary: Demographic Information. State of California. 2025. Available online: https://ebudget.ca.gov/2025-26/pdf/BudgetSummary/DemographicInformation.pdf (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Blake, S. Californians Who Left for Remote Work Have Shown ‘Signs of Returning’. Newsweek, 25 November 2024. Available online: https://www.newsweek.com/california-sees-surge-people-moving-state-1986685 (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- California Department of Finance, CDOF. Demographic Projections and Migration Trends. 2024. Available online: https://dof.ca.gov/Forecasting/Demographics (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Glaeser, E.L.; Gottlieb, J.D. The wealth of cities: Agglomeration economies and spatial equilibrium in the United States. J. Econ. Lit. 2009, 47, 983–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roback, J. Wages, rents, and the quality of life. J. Political Econ. 1982, 90, 1257–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalieri, M.C.; Luu, N.; Causa, O. Migration, Housing and Regional Disparities: A Gravity Model of Interregional Migration with an Application to Selected OECD Countries; OECD Economic Department Working Papers No. 1691; OECD: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamond, R. The determinants and welfare implications of US workers’ diverging location choices by skill: 1980–2000. Am. Econ. Rev. 2016, 106, 479–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Census Bureau. American Community Survey and Puerto Rico Community Survey Design and Methodology; U.S. Government Printing Office: Washington, DC, USA, 2024.

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2025; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 17, StataCorp LLC: College Station, TX, USA, 2021. Available online: https://www.stata.com/manuals17/i.pdf (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Hernández-Murillo, R.; Ott, L.S.; Owyang, M.T.; Whalen, D. Patterns of Interstate Migration in the United States from the Survey of Income and Program Participation. Fed. Reserve Bank St. Louis Rev. 2011, 95, 169–185. [Google Scholar]

- Molloy, R.; Smith, C.L.; Wozniak, A. Internal migration in the United States. J. Econ. Perspect. 2011, 25, 173–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wozniak, A. Are college graduates more responsive to distant labor market opportunities? J. Hum. Resour. 2010, 45, 944–970. [Google Scholar]

- Dietz, J.; Li, B.; Castañeda, E. Keeping in motion or staying put: Internal migration in the United States and China. Societies 2023, 13, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, N.; Molloy, R.; Smith, C.; Wozniak, A. The economics of internal migration: Advances and policy questions. J. Econ. Lit. 2023, 61, 144–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oswald, F. The effect of homeownership on the option value of regional migration. Quant. Econ. 2019, 10, 1453–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, W.; Lisowksi, W. Prospect theory and the decision to move or stay. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, E7432–E7440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, W.H.; Liaw, K.; Wright, R.; White, M. Migration Within the United States: Role of Race-Ethnicity; Brookings-Wharton Papers on Urban Affairs; Brookings Institution Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2005; pp. 207–262. [Google Scholar]

- Kane, K. How have American migration patterns changed in the COVID era? Growth Change 2024, 55, e12742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Public Policy Institute of California. Immigrants in California. 2024. Available online: https://www.ppic.org/publication/immigrants-in-california/ (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Castleman, T. California’s Big Shift: Asian Population Rising, Latinos Declining. Governing. 22 April 2025. Available online: https://www.governing.com/workforce/californias-big-shift-asian-population-rising-latinos-declining (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Perez, C.A.; Johnson, H. How Has California’s Immigrant Population Changed over Time? Public Policy Institute of California: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2024; Available online: https://www.ppic.org/blog/how-has-californias-immigrant-population-changed-over-time/ (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Saxenian, A. Silicon Valley’s New Immigrant Entrepreneurs; Working Paper No. 15; Center for Comparative Immigration Studies, University of California at San Diego: San Diego, CA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, A. Exploratory and spatial analysis of disability among older Asian Indians. Appl. Geogr. 2019, 113, 102099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- California Department of Finance, Demographic Research Unit. County Population Projections by Age, Sex, Race/Ethnicity (P-2). 2024. Available online: https://dof.ca.gov/forecasting/demographics/projections/ (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Center for Social Innovation, University of California, Riverside. State of Immigrants in the Inland Empire; University of California, Riverside: Riverside, CA, USA, 2018; Available online: https://socialinnovation.ucr.edu/state-immigrants-inland-empire (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Li, W. Ethnoburb: The New Ethnic Community in Urban America; University of Hawaii Press: Honolulu, HI, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Logan, J.R.; Alba, R.D.; Zhang, W. Immigrant enclaves and ethnic communities in New York and Los Angeles. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2002, 67, 299–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, A.; Kitson, K.; Pryor, L.; Ramos-Yamamoto, A.; Saucedo, M. California’s Poverty Rate Soars to Alarmingly High Levels in 2023; California Budget & Policy Center: Sacramento, CA, USA, 2024; Available online: https://calbudgetcenter.org/resources/californias-poverty-rate-soars-to-alarmingly-high-levels-in-2023/ (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Bohn, S.; Danielson, C.; Kimberlin, S.; Malagon, P.; Stevens, C.; Wimer, C. Poverty in California; Public Policy Institute of California: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2025; Available online: https://www.ppic.org/publication/poverty-in-california/ (accessed on 10 August 2025).

- Blumenberg, E.; Siddiq, F. Commute Distance and Jobs-Housing Fit in Los Angeles; Policy Brief; UCLA Lewis Center for Regional Policy Studies: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Public Policy Institute of California. Rural California. 2024. Available online: https://www.ppic.org/publication/rural-california/ (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Soto Nishimura, A.; Czaika, M. Exploring migration determinants: A meta-analysis of migration drivers and estimates. J. Int. Migr. Integr. 2024, 25, 621–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, W.H.; Liaw, K.L. Interstate migration of Hispanics, Asians and Blacks: Cultural constraints and middle class flight. Popul. Stud. Cent. Res. Rep. 2005, 5, 575. [Google Scholar]

- Katz, B. State of Metropolitan America: On the Front Lines of Demographic Transformation. Brookings Institution, 18 October 2010. Available online: https://www.brookings.edu/articles/the-state-of-metropolitan-america-metros-on-the-front-lines-of-demographic-transformation/ (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Khater, S.; Yao, K. In Pursuit of Affordable Housing: The Migration of Homebuyers Within the US—Before and After the Pandemic; Research Note; Freddie Mac: McLean, VA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Baldassare, M.; Bonner, D.; Mora, L.; Thomas, D. PPIC Statewide Survey: Californians and Their Government; Public Policy Institute of California: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

| Variables | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| In-migration rate | 5.49 | 10.39 | 9.72 | 13.35 | 9.28 | 12.45 |

| Demographic | ||||||

| Asian | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.10 |

| Black | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.09 | 0.06 |

| Hispanic | 0.26 | 0.19 | 0.28 | 0.19 | 0.28 | 0.18 |

| Age 30 or younger | 0.40 | 0.04 | 0.39 | 0.04 | 0.39 | 0.04 |

| College degree or greater | 0.23 | 0.08 | 0.25 | 0.10 | 0.26 | 0.10 |

| Economic | ||||||

| Earned income | $30,612 | $9016 | $33,761 | $12,830 | $34,859 | $12,947 |

| Supplemental poverty | 0.11 | 0.04 | 0.16 | 0.06 | 0.16 | 0.05 |

| Unemployment | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.01 |

| Medicaid | 0.24 | 0.07 | 0.23 | 0.08 | 0.24 | 0.08 |

| Medicare | 0.18 | 0.04 | 0.18 | 0.04 | 0.18 | 0.04 |

| Housing | ||||||

| Rent burden | 0.48 | 0.04 | 0.44 | 0.05 | 0.48 | 0.04 |

| Total utility cost | $11,739 | $1817 | $10,764 | $1988 | $10,607 | $1883 |

| Observations | 200 | 281 | 281 | |||

| Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic | |||

| Asian | 40.83 *** | 36.84 *** | 37.91 *** |

| (9.64) | (10.10) | (9.83) | |

| Black | 3.87 | −9.33 | −10.19 |

| (7.71) | (8.76) | (8.98) | |

| Hispanic | 22.83 *** | 16.95 *** | 17.27 *** |

| (6.41) | (6.03) | (5.87) | |

| Age 30 or younger | 20.78 | 12.73 | 12.77 |

| (16.27) | (21.52) | (21.65) | |

| College degree or greater | 39.80 *** | 47.20 *** | 47.08 *** |

| (11.91) | (12.83) | (12.51) | |

| Economic | |||

| Log earned income | −0.03 | −0.03 | |

| (0.08) | (0.08) | ||

| Supplemental poverty | 22.45 ** | 19.10 * | |

| (10.19) | (10.85) | ||

| Unemployment | 46.08 | 40.10 | |

| (40.63) | (40.413) | ||

| Medicaid | 14.34 | 13.52 | |

| (13.65) | (13.58) | ||

| Medicare | −15.48 | −14.76 | |

| (22.38) | (22.35) | ||

| Housing | |||

| Rent burden | 45.86 | ||

| (40.94) | |||

| Total utility cost | 0.00 | ||

| (0.00) | |||

| 2022 year | 2.10 *** | 1.45 | 1.64 * |

| (0.37) | (0.93) | (0.97) | |

| 2023 year | 1.39 *** | 0.74 | 0.93 |

| (0.34) | (0.81) | (0.85) | |

| Constant | −21.20 *** | −21.20 | −21.65 |

| (8.21) | (13.52) | (13.6) | |

| Observations | 762 | 762 | 762 |

| R-squared | 0.11 | 0.14 | 0.15 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Sharma, A. An Analysis of In-Migration Patterns for California: A Two-Way Fixed Effects Approach Utilizing a Pooled Sample. Populations 2026, 2, 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/populations2010002

Sharma A. An Analysis of In-Migration Patterns for California: A Two-Way Fixed Effects Approach Utilizing a Pooled Sample. Populations. 2026; 2(1):2. https://doi.org/10.3390/populations2010002

Chicago/Turabian StyleSharma, Andy. 2026. "An Analysis of In-Migration Patterns for California: A Two-Way Fixed Effects Approach Utilizing a Pooled Sample" Populations 2, no. 1: 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/populations2010002

APA StyleSharma, A. (2026). An Analysis of In-Migration Patterns for California: A Two-Way Fixed Effects Approach Utilizing a Pooled Sample. Populations, 2(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/populations2010002