Abstract

Background: Handgrip strength (HGS) is strongly recommended for use in clinical settings because it is a convenient assessment of muscle strength and a robust prognostic indicator of health. However, it may lack use in clinical settings, and may not be well understood by healthcare providers and patients. We sought to determine the healthcare provider and patient perceptions of HGS in an internal medicine resident clinic. Methods: Healthcare providers were presented with didactic sessions for HGS and engaged in routine follow-up meetings. HGS was measured on eligible older adult patients during an approximately 9-month phased study period. Both healthcare providers and patients were asked to complete a questionnaire with 10-point Likert scale response items regarding their experiences with HGS. Results were presented as descriptive. Results: Overall, patients had a positive perception of HGS, as they understood HGS instructions (score: 9.8 ± 0.7), their results (score: 9.5 ± 1.3), and found value in HGS for their health (score: 8.4 ± 2.3). However, healthcare providers were generally neutral about HGS, such that at study end HGS was viewed as moderately valuable for their practice (score: 6.0 ± 2.1) and patients (score: 6.0 ± 2.1). Conclusions: Overall, patients had a positive perception of HGS, but healthcare providers were neutral. Our findings should be used to guide HGS for possible implementation and quality management in appropriate healthcare settings.

1. Introduction

Handgrip strength (HGS) is a convenient, reliable, and non-invasive measure of overall muscle strength [1]. Protocol guidelines for collecting HGS advise that persons squeeze a handgrip dynamometer with maximal effort for multiple trials on each hand while seated [2]. This feasible protocol enables HGS to be ascertained privately in patient’s rooms during healthcare provider visits and allows for the inclusion of a wide range of in patient functional abilities [3]. Certain handgrip dynamometers (e.g., hydraulic), which are used to measure HGS, have a sustainable energy source that permits portability and use without electronic plug-in or batteries. Low HGS is associated with several clinically relevant health conditions such as chronic cardiometabolic morbidities, neurogenerative diseases, and functional limitations [4]. Weakness, which is determined by HGS, is present when strength capacity is below a pre-specified cut-point, and nationally representative age- and sex-specific HGS percentiles enable peer-comparisons of muscle strength across the lifespan [5]. As such, HGS is regarded as a vital sign and biomarker of health status that is strongly recommended for routine collection by healthcare providers [6].

Despite the rich clinical utility and prognostic value of HGS, healthcare providers may not frequently be using HGS for patient care [7]. Efforts to implement HGS in clinical settings have been limited but fruitful. For example, an implementation study of HGS in five United Kingdom acute medical wards found that although there were multiple facilitators and barriers to implementing HGS among clinical staff and patients, HGS measurement helped to identify a high proportion of weak patients [8]. Moreover, a quality improvement study of HGS implementation in dietitian care on inpatient rehabilitation units revealed that HGS was simple to use, did not impact dietitian efficiency, and supported value to nutrition assessments including follow-ups [9]. While HGS is trending toward clinical implementation as part of the translational research process, it remains important to understand the perceptions of HGS from healthcare providers and patients in different healthcare settings so that adoption can be better specified. Accordingly, this pilot study sought to examine the perceptions of HGS among healthcare providers and patients in an internal medicine resident clinic.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

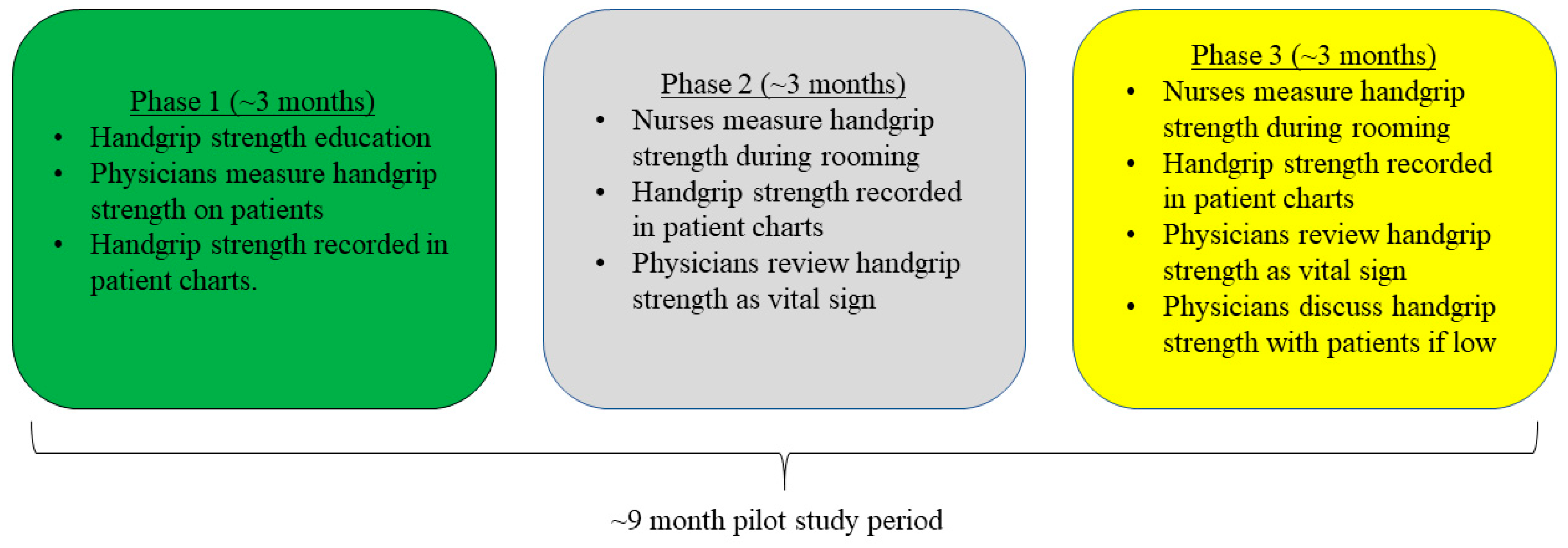

We utilized a cross-sectional design for this pilot study, which occurred in an internal medicine resident clinic. Our pilot study design followed quality improvement guidelines and was modeled from other previous work [8,10]. At the beginning of the study, there were 30 eligible members of the healthcare team (i.e., 24 medical residents, 4 consistent attending physicians, and 2 consistent nurses) practicing in the clinic. Resident physicians worked on rotations in the clinic while attending physicians were assigned to alternating shifts. To ease familiarity and workflow of HGS measurements in the clinic, the design of this pilot study was phased into 3 segments (each of which was about 3 months in duration) across an approximate 9-month study period.

In the first phase, relevant healthcare providers engaged in an educational session about HGS, which included background, clinical relevance, directions for measurement, and practice with peers. Residents were also asked to perform HGS measurements during eligible patient visits and record values in patient charts. During the second phase, nurse personnel were asked to perform HGS measurements during the rooming process, and record HGS values in patient charts as a vital sign, so that residents could view HGS values before patient visits. In the third phase, nurse personnel still performed HGS measurements during rooming and recorded values in charts, but healthcare providers were encouraged to discuss low HGS values with patients as a marker of weakness. Reminders and direction sheets for HGS were posted in healthcare provider offices and patient visit rooms. Figure 1 provides a schematic of the study activities.

Figure 1.

Schematic of Study Activities.

Patients visiting the internal medicine resident clinic were eligible for HGS testing if they were aged at least 65-years, able to squeeze a handgrip dynamometer with a hand, without severe hand or wrist arthritis, a dementia diagnosis, or neurological impairment (e.g., stroke, Parkinson’s disease), and were not on hospice status. However, due to a larger patient volume, limited healthcare provider personnel, and pilot nature of this investigation, healthcare providers may not have performed HGS testing on eligible patients at their discretion (e.g., time limitations). The North Dakota State University Institutional Review Board (IRB0004892) determined this pilot study was exempt and therefore informed consent was provided by completing questionnaires in order to maintain anonymity. Healthcare providers and patients completing questionnaires about HGS gave consent to participate by opting to complete the questionnaire because all responses were voluntary, anonymous, and unidentifiable.

2.2. Measures

A Jamar hydraulic handgrip dynamometer (Lafayette Instrument Company; Lafayette, IN) was used to measure HGS. Protocol guidelines for measuring HGS guided our testing [2]. Specifically, healthcare providers explained the HGS measurement, fitted the dynamometer to the hand size of each patient, and allowed a practice trial. Patients were seated in a chair with their back against the rest and forearms likewise against chair rests. The dynamometer was grasped by patients with their elbow flexed at 90° and hand in a neutral position (i.e., knuckles vertical). Beginning on the right hand, patients were asked to squeeze the dynamometer with maximal effort, exhaling while squeezing, while the healthcare provider gave verbal encouragement. Patients completed two HGS measures on each hand, alternating between hands. The highest recorded HGS measurement was reviewed by healthcare providers. Males and females with HGS <26-kg and <16-kg were considered weak [11]. Two HGS trials on each hand are appropriate when categorizing HGS [12].

After engaging in HGS testing, patients were asked to voluntarily complete an anonymous questionnaire regarding their perceptions of HGS. The questionnaire was modeled on a similar study [8] and was created by the investigators to collect relevant insights. There were five items on the questionnaire that were assessed with a 10-point Likert scale which asked (1) “how much did you understand the instructions given to you by your healthcare provider about how to complete a handgrip strength measurement?”, (2) “how much did you understand what the handgrip strength measurement was evaluating?”, (3) “how much did you understand the results from your handgrip strength test?”, (4) “how valuable did you find the handgrip measurement for your health?”, and (5) “how much would you recommend handgrip strength to a peer for their health?”. Completed patient questionnaires were aggregately placed in a secure location to maintain anonymity.

At baseline and end of each phase, healthcare providers were asked to voluntarily complete anonymous questionnaires about their perceptions and experiences with HGS testing. This questionnaire was similarly modeled from another study [8] and was created by the investigators to collect relevant insights. Although some of the items in the healthcare provider questionnaires were consistent across the study period, others were created to be specified to project phase completed at time of administration, which is part of quality improvement assessments [10]. Completed questionnaires were aggregately placed in a secure location to maintain anonymity. Items included in healthcare provider and patient questionnaires were created to be brief and relevant so that the time burden could be mitigated. Responses from the healthcare provider and patient questionnaires were reported as mean ± standard deviation given his pilot study was descriptive in nature.

3. Results

Table 1 presents the results of HGS measurement perceptions from 93 patients. The perceptions of HGS from patients were overall positive, such that patients understood HGS instructions (score: 9.8 ± 0.7), what HGS was evaluating (score: 9.6 ± 1.3), and results of their HGS test (score: 9.5 ± 1.3). Patients also found HGS testing to be valuable to their health (score: 8.4 ± 2.3) and would recommend HGS to a peer for health (score: 8.7 ± 2.3).

Table 1.

Patient Perceptions of Handgrip Strength Measurement.

The results of the healthcare provider perceptions to HGS testing are shown in Table 2. At baseline, there were 24 healthcare providers that voluntarily completed a questionnaire. Overall, healthcare providers felt educated on HGS (score: 7.3 ± 2.1), and were comfortable measuring HGS on a patient (score: 8.5 ± 1.8) and explaining its importance (score: 7.6 ± 1.9). At the conclusion of Phase 1, 20 healthcare providers reported being mostly comfortable measuring HGS on patients (score: 6.9 ± 3.0), but may have perceived HGS as lacking value to their patients (score: 3.7 ± 2.1). The frequency of measuring HGS on patients was also reported as lower (score: 3.1 ± 2.0). The frequency of healthcare providers measuring HGS on patients was reported as lower at the end of Phase 2 (score: 2.6 ± 1.4). However, there were 19 healthcare providers that indicated they were neutral about the value of HGS to patients (score: 4.7 ± 2.2) and their practice (score: 5.1 ± 2.1).

Table 2.

Healthcare Provider Perceptions to Handgrip Strength Testing.

4. Discussion

The principal findings of this pilot investigation suggest that older patients visiting an internal medicine resident clinic well-understood HGS testing, including instructions, HGS as a strength capacity measurement, and their HGS test results. Patients also found value in HGS measurements for health, and would recommend HGS to a peer for their health. Overall, while healthcare providers were comfortable with HGS, they may have considered HGS less valuable for patients relative to their patient’s perceptions. Our results should be used to guide patient-physician relations, and elevate quality improvement in healthcare settings by introducing measures that may improve patient care.

Our findings for patient perceptions of HGS are consistent with another investigation that sought to implement HGS in clinical practice, whereby patients understood HGS test directions and felt that HGS had value for health [8]. This understanding and acceptability of HGS by patients may help support the readiness for implementation in clinical practice as appropriate [13], as muscle strength testing is a common aspect of patient physical examinations [14], and persons that are receiving routine healthcare may benefit from HGS testing because their strength capacity is generally lower [15]. Our findings also demonstrate that patients understand HGS results as they pertain to their muscle strength. Blood pressure is a routine assessment in clinical settings that is likewise well understood by patients, although low HGS may be a better predictor of early all-cause and cardiovascular mortality than systolic blood pressure [16]. Having measures of both muscle and cardiovascular health in clinical settings may broaden patient assessments and elevate quality assurance in healthcare settings.

Resident physicians frequently expressed challenges in utilizing HGS measurements due to uncertainty in managing weakness. Like hypertension, low HGS is predictive of disease, disability, and time to mortality [3]. However, while hypertension has clear guidelines and well-studied treatment options [17], HGS needs further development in this regard. As such, residents were consulted to utilize prescriptive physical activity, nutrition, and physical therapy for patients with low HGS, but without clear guidelines and evidence of benefit, consistency for utilizing HGS may not persist. A predictable barrier to any new measure, including HGS, is time, as transitioning new tools and methods from research into clinical practice can pose time challenges in healthcare settings. Obtaining HGS measurements and synthesizing a management plan for patients with low HGS was deprioritized over other chronic diseases. More research in examining the role of HGS in other, non-teaching clinics may reduce time and learning curves, and continuing to study the implications of HGS in expanding education to physicians and trainees on these implications, including defining interventions for low HGS are all expected to elevate acceptance and use of HGS by healthcare providers.

Patients value discussions with their healthcare provider [18], but time is often limited due to provider workload [19]. However, utilizing new tools and methods to improve patient outcomes is nonetheless important for quality improvement [20]. For example, certain internal medicine clinics might benefit from routine HGS measurements because they help to predict hospital specific outcomes such as length of stay and quality of life [21]. Our findings suggest while healthcare providers that completed our questionnaires overall understood HGS and were comfortable in measurement with patients, they remained neutral regarding value, which differed from their patient’s perceptions about HGS. Transformative healthcare settings such as age friendly clinics may help to provide more specification to including HGS as part of mobility assessments in the “4Ms” [22,23]. Healthcare providers should continue seeking new methods and tools for improving patient care including HGS, but consideration should be provided for utility in specific healthcare settings, which includes patient applicability.

Some limitations should be noted. Completion rates for HGS were not reported herein for maintaining regulatory compliance. However, items included in healthcare provider questionnaires could be used as a HGS completion rate proxy, which suggested completion might have been lower, possibly due to low staffing. We experienced attrition in healthcare provider responses to questionnaires because they were voluntary. Therefore, bias in respondents may have influenced our findings, albeit the direction of bias is unknown, and a more targeted approach to consistently collecting healthcare provider responses overtime may have helped in mitigating this attrition. A phased approach for measuring HGS was adopted in our pilot study design for easing transitions and learning experiences. Questionnaires for patients and healthcare providers were truncated for reducing time burden, and items included in provider questionnaires were modified to fit the pilot study phase and experiences. Moreover, the questionnaires for patients and healthcare providers were created by the investigators and were without reliability testing, but no well-validated questionnaires on this topic were known to be available. Our findings were presented as descriptive in effort to gather perceptions of HGS from patients and healthcare providers, which may help in the implementation of HGS and quality improvement in relevant healthcare settings.

Despite our limitations, our study has several future research implications. For example, our sample included older patients visiting an internal medicine resident clinic. The methodological framework of our investigation may have applicability to other types of patients (e.g., middle-aged adults); clinical settings (e.g., family medicine); and healthcare providers (e.g., non-residents). Completing HGS trainings at a student level may help to segue HGS use to clinical practice. Although our sample size from patient questionnaires was adequate given the study design and limitations, we experienced declines in healthcare provider feedback, but sampling may increase when other types of patients, clinical settings, and healthcare providers are again considered. Likewise, shorter response intervals for healthcare provider questionnaires may elevate response rates, and examining patient perceptions of HGS longitudinal designs may enable the examination of change.

5. Conclusions

The findings from our pilot study suggest that perceptions of HGS were overall positive in patients visiting an internal medicine resident clinic. Specifically, patients understood HGS and found the measure as valuable to health. Provider perceptions of HGS were relatively neutral. Our findings should be used to guide implementation of HGS in clinics and quality improvement as appropriate. Credence should be placed into the utility of HGS when considering the types of patients visiting clinics, and time for use before adoption.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.M. and K.J.; methodology, R.M. and K.J.; investigation, M.M., R.M. and K.J.; resources, R.M.; writing—original draft preparation, R.M.; writing—review and editing, M.M., K.J., L.D., S.H., P.L., G.M., A.O., J.R. and D.T.; visualization, R.M.; supervision, K.J., L.D., J.R., D.T. and R.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Research reported in this publication was supported as a student pilot project by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R15AG072348 (to RM). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. This study was also supported, in part, by funding from the Health Resources & Services Administration (HRSA) of the United States Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) as part of an award totaling USD 3.75 million with 15% financed with non-governmental sources. The contents are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of, nor an endorsement by HRSA, HHS, or the United States Government. Likewise, this work was partially supported by the INBRE Undergraduate Biomedical Research Program at North Dakota State University.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of North Dakota State University (IRB0004892; 23 August 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because of regulatory compliance. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to ryan.mcgrath@ndsu.edu.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bhasin, S.; Travison, T.G.; Manini, T.M.; Patel, S.; Pencina, K.M.; Fielding, R.A.; Magaziner, J.M.; Newman, A.B.; Kiel, D.P.; Cooper, C. Sarcopenia Definition: The Position Statements of the Sarcopenia Definition and Outcomes Consortium. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2020, 68, 1410–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, H.C.; Denison, H.J.; Martin, H.J.; Patel, H.P.; Syddall, H.; Cooper, C.; Sayer, A.A. A Review of the Measurement of Grip Strength in Clinical and Epidemiological Studies: Towards a Standardised Approach. Age Ageing 2011, 40, 423–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGrath, R.P.; Kraemer, W.J.; Snih, S.A.; Peterson, M.D. Handgrip Strength and Health in Aging Adults. Sports Med. 2018, 48, 1993–2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGrath, R.; Johnson, N.; Klawitter, L.; Mahoney, S.; Trautman, K.; Carlson, C.; Rockstad, E.; Hackney, K.J. What Are the Association Patterns between Handgrip Strength and Adverse Health Conditions? A Topical Review. SAGE Open Med. 2020, 8, 2050312120910358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrath, R.; Cawthon, P.; Clark, B.; Fielding, R.; Lang, J.; Tomkinson, G. Recommendations for Reducing Heterogeneity in Handgrip Strength Protocols. J. Frailty Aging 2022, 11, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohannon, R.W. Grip Strength: An Indispensable Biomarker for Older Adults. Clin. Interv. Aging 2019, 14, 1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruyère, O.; Beaudart, C.; Reginster, J.-Y.; Buckinx, F.; Schoene, D.; Hirani, V.; Cooper, C.; Kanis, J.A.; Rizzoli, R.; McCloskey, E. Assessment of Muscle Mass, Muscle Strength and Physical Performance in Clinical Practice: An International Survey. Eur. Geriatr. Med. 2016, 7, 243–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, K.; May, C.R.; Patel, H.P.; Baxter, M.; Sayer, A.A.; Roberts, H.C. Implementation of Grip Strength Measurement in Medicine for Older People Wards as Part of Routine Admission Assessment: Identifying Facilitators and Barriers Using a Theory-Led Intervention. BMC Geriatr. 2018, 18, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandhu, R.; Lee, T. Incorporating Handgrip Strength Examination into Dietetic Practice: A Quality Improvement Project. Nutr. Clin. Pract. 2023, 38, 904–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, B.; Vaux, E.; Olsson-Brown, A. How to Get Started in Quality Improvement. BMJ 2019, 364, k5408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alley, D.E.; Shardell, M.D.; Peters, K.W.; McLean, R.R.; Dam, T.-T.L.; Kenny, A.M.; Fragala, M.S.; Harris, T.B.; Kiel, D.P.; Guralnik, J.M. Grip Strength Cutpoints for the Identification of Clinically Relevant Weakness. J. Gerontol. Ser. Biomed. Sci. Med. Sci. 2014, 69, 559–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reijnierse, E.M.; de Jong, N.; Trappenburg, M.C.; Blauw, G.J.; Butler-Browne, G.; Gapeyeva, H.; Hogrel, J.Y.; McPhee, J.S.; Narici, M.V.; Sipilä, S.; et al. Assessment of Maximal Handgrip Strength: How Many Attempts are Needed? J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2017, 8, 466–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doherty, W.J.; Stubbs, T.A.; Chaplin, A.; Langford, S.; Sinclair, N.; Ibrahim, K.; Reed, M.R.; Sayer, A.A.; Witham, M.D.; Sorial, A.K. Implementing Grip Strength Assessment in Hip Fracture Patients: A Feasibility Project. J. Frailty Sarcopenia Falls 2021, 6, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bohannon, R.W. Considerations and Practical Options for Measuring Muscle Strength: A Narrative Review. BioMed Res. Int. 2019, 2019, 8194537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, H.C.; Syddall, H.E.; Sparkes, J.; Ritchie, J.; Butchart, J.; Kerr, A.; Cooper, C.; Sayer, A.A. Grip Strength and Its Determinants among Older People in Different Healthcare Settings. Age Ageing 2014, 43, 241–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, D.P.; Teo, K.K.; Rangarajan, S.; Lopez-Jaramillo, P.; Avezum, A.; Orlandini, A.; Seron, P.; Ahmed, S.H.; Rosengren, A.; Kelishadi, R. Prognostic Value of Grip Strength: Findings from the Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiology (PURE) Study. Lancet 2015, 386, 266–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Unger, T.; Borghi, C.; Charchar, F.; Khan, N.A.; Poulter, N.R.; Prabhakaran, D.; Ramirez, A.; Schlaich, M.; Stergiou, G.S.; Tomaszewski, M. 2020 International Society of Hypertension Global Hypertension Practice Guidelines. Hypertension 2020, 75, 1334–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, M. What Patients Want from Their Doctors. BMJ 2003, 326, 1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsiga, E.; Panagopoulou, E.; Sevdalis, N.; Montgomery, A.; Benos, A. The Influence of Time Pressure on Adherence to Guidelines in Primary Care: An Experimental Study. BMJ Open 2013, 3, e002700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyler, A.; Glasgow, R. Implementing Improvements: Opportunities to Integrate Quality Improvement and Implementation Science. Hosp. Pediatr. 2021, 11, 536–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNicholl, T.; Curtis, L.; Dubin, J.A.; Mourtzakis, M.; Nasser, R.; Laporte, M.; Keller, H. Handgrip Strength Predicts Length of Stay and Quality of Life in and out of Hospital. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 39, 2501–2509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beaudart, C.; Rolland, Y.; Cruz-Jentoft, A.J.; Bauer, J.M.; Sieber, C.; Cooper, C.; Al-Daghri, N.; Araujo de Carvalho, I.; Bautmans, I.; Bernabei, R. Assessment of Muscle Function and Physical Performance in Daily Clinical Practice. Calcif. Tissue Int. 2019, 105, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emery-Tiburcio, E.E.; Mack, L.; Zonsius, M.C.; Carbonell, E.; Newman, M. The 4Ms of an Age-Friendly Health System. AJN Am. J. Nurs. 2021, 121, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).