The Psychology of Working Students: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Rationale

1.2. Objectives

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protocol and Registration

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Information Sources

2.4. Search

2.5. Selection of Sources of Evidence

2.6. Data Charting Process

2.7. Data Items

2.8. Critical Appraisal of Individual Sources of Evidence

2.9. Synthesis of Results

3. Results

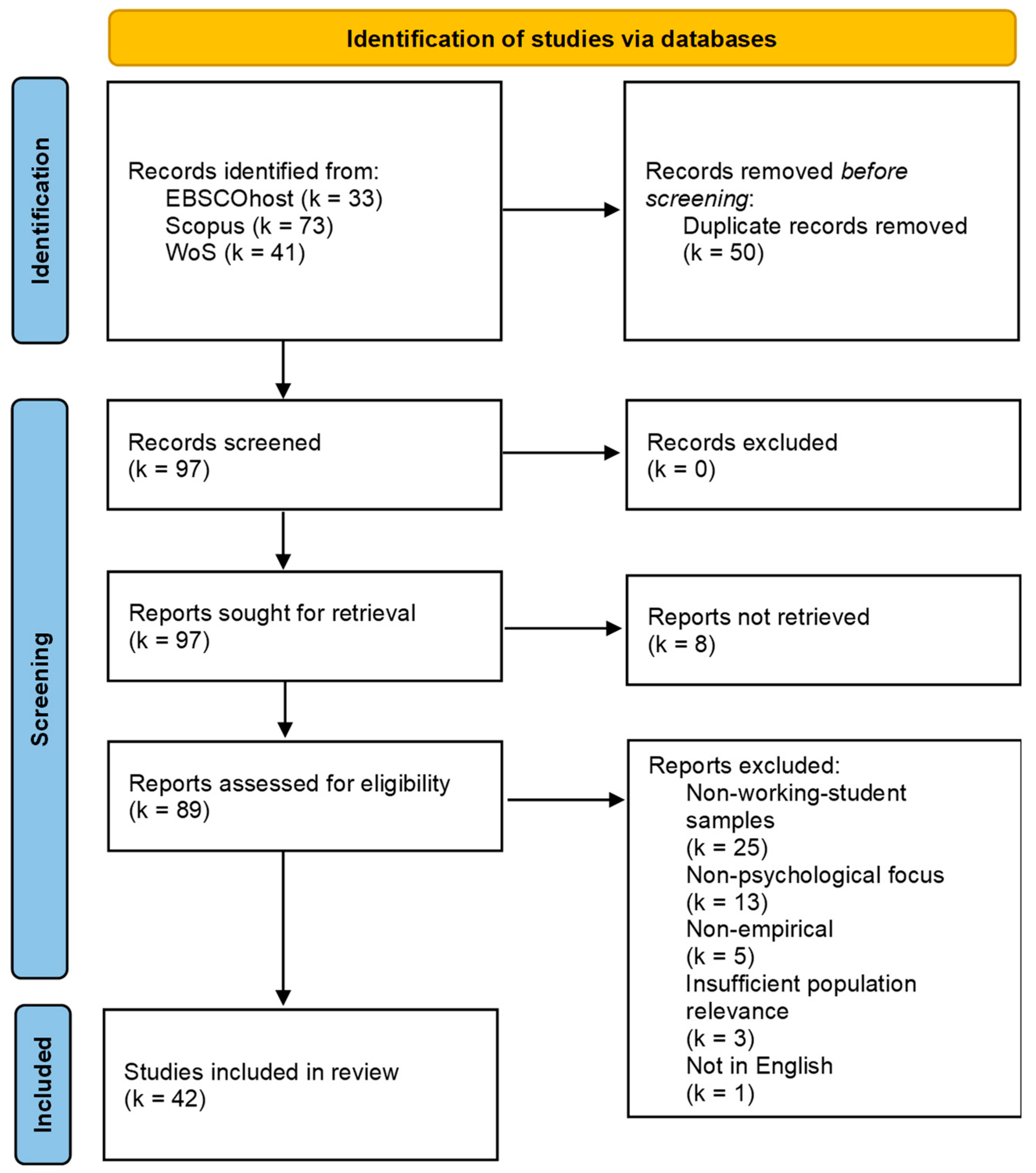

3.1. Selection of Sources of Evidence

3.2. Characteristics of Sources of Evidence

3.3. Critical Appraisal Within Sources of Evidence

3.4. Results of Individual Sources of Evidence

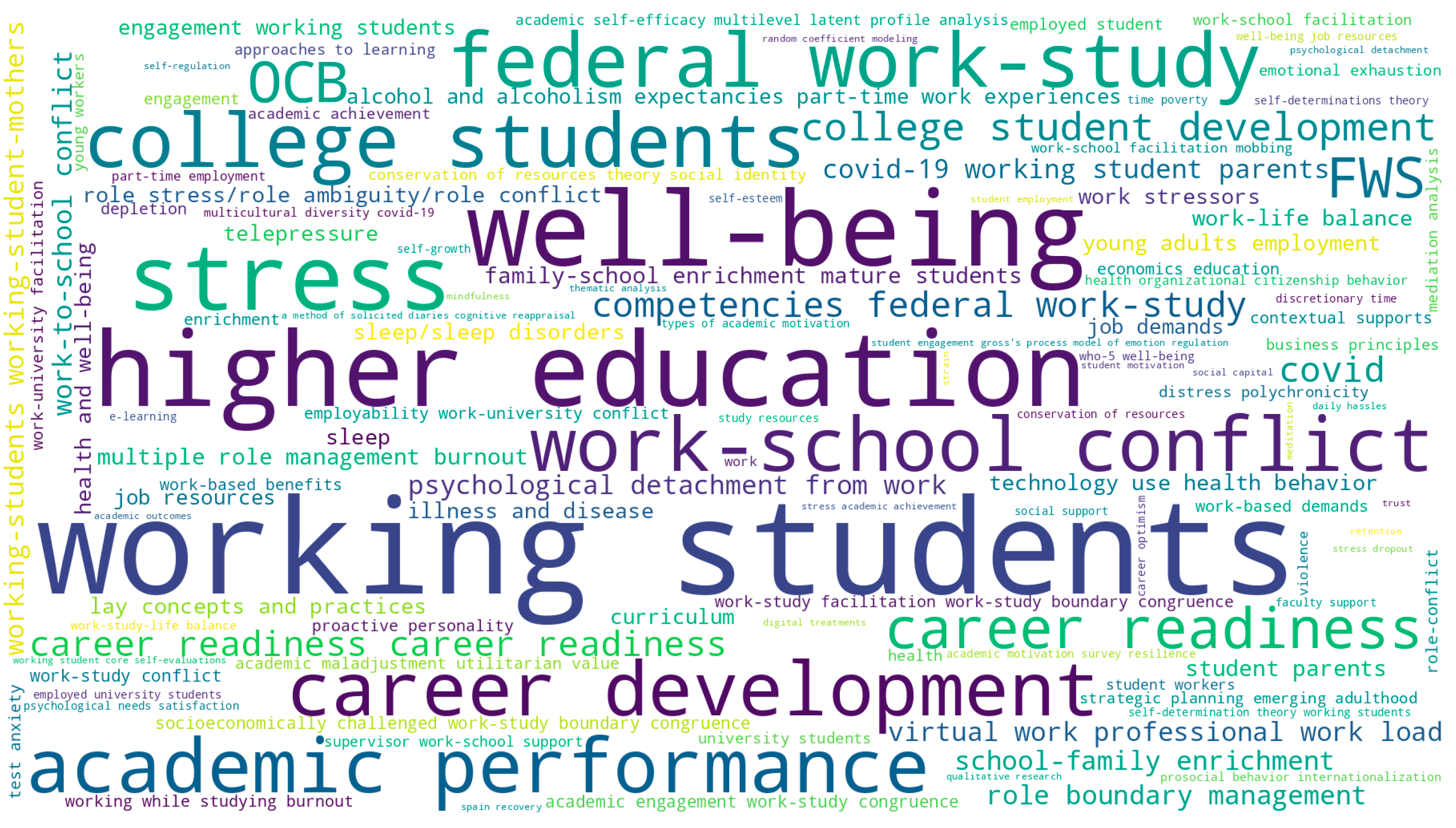

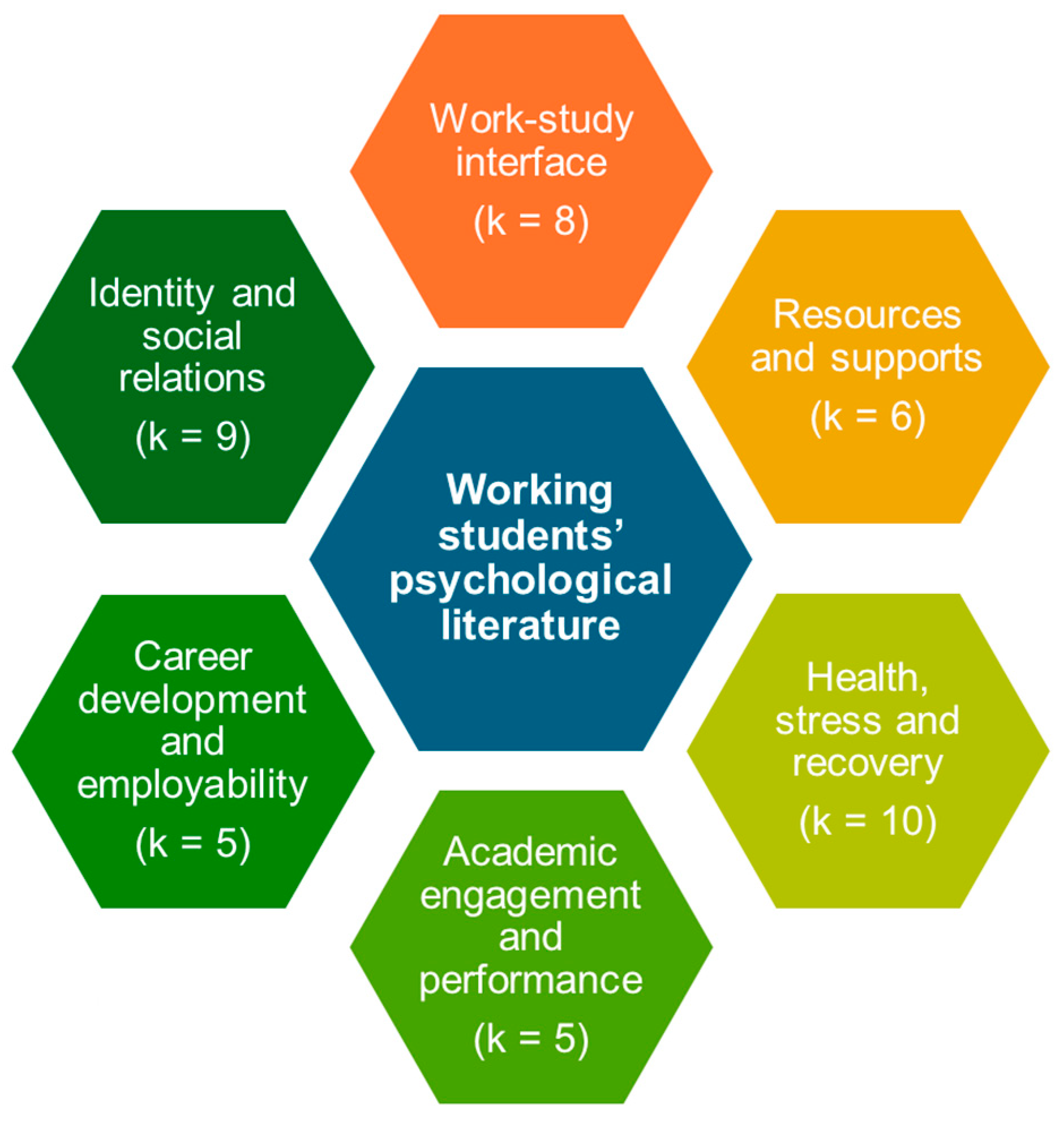

3.5. Synthesis of Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary and Interpretation of Key Findings

4.2. Implications for Research, Institutions, and Practice

4.3. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) Checklist

| Section | Item | PRISMA-ScR Checklist Item | Reported on Page Number |

|---|---|---|---|

| Title | |||

| Title | 1 | Identify the report as a scoping review. | 1 |

| Abstract | |||

| Structured summary | 2 | Provide a structured summary that includes (as applicable): background, objectives, eligibility criteria, sources of evidence, charting methods, results, and conclusions that relate to the review questions and objectives. | 1 |

| Introduction | |||

| Rationale | 3 | Describe the rationale for the review in the context of what is already known. Explain why the review questions/objectives lend themselves to a scoping review approach. | 2–3 |

| Objectives | 4 | Provide an explicit statement of the questions and objectives being addressed with reference to their key elements (e.g., population or participants, concepts, and context) or other relevant key elements used to conceptualize the review questions and/or objectives. | 3 |

| Methods | |||

| Protocol and registration | 5 | Indicate whether a review protocol exists; state if and where it can be accessed (e.g., a Web address); and if available, provide registration information, including the registration number. | 3 |

| Eligibility criteria | 6 | Specify characteristics of the sources of evidence used as eligibility criteria (e.g., years considered, language, and publication status), and provide a rationale. | 3 |

| Information sources | 7 | Describe all information sources in the search (e.g., databases with dates of coverage and contact with authors to identify additional sources), as well as the date the most recent search was executed. | 4 |

| Search | 8 | Present the full electronic search strategy for at least 1 database, including any limits used, such that it could be repeated. | 4–5 |

| Selection of sources of evidence | 9 | State the process for selecting sources of evidence (i.e., screening and eligibility) included in the scoping review. | 5 |

| Data charting process | 10 | Describe the methods of charting data from the included sources of evidence (e.g., calibrated forms or forms that have been tested by the team before their use, and whether data charting was done independently or in duplicate) and any processes for obtaining and confirming data from investigators. | 5 |

| Data items | 11 | List and define all variables for which data were sought and any assumptions and simplifications made. | 5 |

| Critical appraisal of individual sources of evidence | 12 | If done, provide a rationale for conducting a critical appraisal of included sources of evidence; describe the methods used and how this information was used in any data synthesis (if appropriate). | 5–6 |

| Synthesis of results | 13 | Describe the methods of handling and summarizing the data that were charted. | 6 |

| Results | |||

| Selection of sources of evidence | 14 | Give numbers of sources of evidence screened, assessed for eligibility, and included in the review, with reasons for exclusions at each stage, ideally using a flow diagram. | 6–7 |

| Characteristics of sources of evidence | 15 | For each source of evidence, present characteristics for which data were charted and provide the citations. | 7–10 |

| Critical appraisal within sources of evidence | 16 | If done, present data on critical appraisal of included sources of evidence (see item 12). | 10–12 |

| Results of individual sources of evidence | 17 | For each included source of evidence, present the relevant data that were charted that relate to the review questions and objectives. | 12–15 |

| Synthesis of results | 18 | Summarize and/or present the charting results as they relate to the review questions and objectives. | 15–16 |

| Discussion | |||

| Summary of evidence | 19 | Summarize the main results (including an overview of concepts, themes, and types of evidence available), link to the review questions and objectives, and consider the relevance to key groups. | 16–19 |

| Limitations | 20 | Discuss the limitations of the scoping review process. | 19–20 |

| Conclusions | 21 | Provide a general interpretation of the results with respect to the review questions and objectives, as well as potential implications and/or next steps. | 20 |

| Funding | |||

| Funding | 22 | Describe sources of funding for the included sources of evidence, as well as sources of funding for the scoping review. Describe the role of the funders of the scoping review. | 20 |

Appendix B

Appendix B.1. JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist for Analytical Cross-Sectional Studies

| Yes | No | Unclear | Not Applicable | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Were the criteria for inclusion in the sample clearly defined? | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| 2. Were the study subjects and the setting described in detail? | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| 3. Was the exposure measured in a valid and reliable way? | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| 4. Were objective, standard criteria used for measurement of the condition? | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| 5. Were confounding factors identified? | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| 6. Were strategies to deal with confounding factors stated? | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| 7. Were the outcomes measured in a valid and reliable way? | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| 8. Was appropriate statistical analysis used? | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

Appendix B.2. JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist for Qualitative Research

| Yes | No | Unclear | Not Applicable | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Is there congruity between the stated philosophical perspective and the research methodology? | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| 2. Is there congruity between the research methodology and the research question or objectives? | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| 3. Is there congruity between the research methodology and the methods used to collect data? | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| 4. Is there congruity between the research methodology and the representation and analysis of data? | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| 5. Is there congruity between the research methodology and the interpretation of results? | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| 6. Is there a statement locating the researcher culturally or theoretically? | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| 7. Is the influence of the researcher on the research, and vice versa, addressed? | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| 8. Are participants, and their voices, adequately represented? | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| 9. Is the research ethical according to current criteria or, for recent studies, and is there evidence of ethical approval by an appropriate body? | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

| 10. Do the conclusions drawn in the research report flow from the analysis, or interpretation, of the data? | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ | ☐ |

Appendix C

List of Excluded Studies with Rationale

| Reference | Reason for Exclusion |

|---|---|

| Akos, P., Joshua Leonard, A., & Hutson, B. (2022). Virtual federal work study and student career development. The Career Development Quarterly, 00, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1002/cdq.12288 | Withdrawn |

| Baker, H. B. (1941). The working student and his grades. The Journal of Educational Research, 35(1), 28–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220671.1941.10881055 | Non-psychological focus |

| Beavis, C., Muspratt, S., & Thompson, R. (2015). ‘Computer games can get your brain working’: Student experience and perceptions of digital games in the classroom. Learning, Media and Technology, 40(1), 21–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2014.904339 | Non-working-student samples |

| Bills, D. B., Helms, L. B., & Ozcan, M. (1995). The impact of student employment on teachers’ attitudes and behaviors toward working students. Youth & Society, 27(2), 169–193. https://doi.org/10.1177/0044118×95027002004 | Non-working-student samples |

| Broughton, E. A., & Otto, S. K. (1999). On-campus student employment: Intentional learning outcomes. Journal of College Student Development, 40(1), 87–89. | Non-psychological focus |

| Bullis, M. (1983). Procedural issues in cooperative work-study programs. Journal of Rehabilitation, 49(2), 33. | Non-empirical |

| Castañeda, L. A., & Han, M. (2025). Everyone benefits when there is another MSW in child welfare: Exploring ways to support Title IV-E MSW student-employees. Journal of Public Child Welfare, 19(3), 700–722. https://doi.org/10.1080/15548732.2024.2357128 | Non-psychological focus |

| Castro, P. F., & Roy, A. S. (2023). El difícil lugar de la autoridad en el trabajo actual: Estudio en empresas de “tendencia” para jóvenes profesionales [The difficult place of authority in today’s work: Study in “trend” companies for young professionals]. Interdisciplinaria, 40, 3. https://doi.org/10.16888/interd.2023.40.3.9Eldif%C3%ADcillugardelaautoridadeneltrabajo | Not in English |

| Cegelka, P. T. (1976). Sex role stereotyping in special education: A look at secondary work study programs. Exceptional Children, 42(6), 323–328. https://doi.org/10.1177/001440297604200604 | Non-empirical |

| Chacon, C., Harper, P., & Harvey, G. F. (1972). Work study in the assessment of the effects of phenothiazines in schizophrenia. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 13(6), 549–554. https://doi.org/10.1016/0010-440X(72)90055-7 | Non-working-student samples |

| Chaffin, J. D., Spellman, C. R., Regan, C. E., & Davison, R. (1971). Two followup studies of former educable mentally retarded students from the Kansas work-study project. Exceptional Children, 37(10), 733–738. https://doi.org/10.1177/001440297103701002 | Non-working-student samples |

| Chue, S., & Billett, S. (2024). Examining workplace affordances within work-study programmes for becoming an engineer. Journal of Workplace Learning, 36(8), 692–708. https://doi.org/10.1108/JWL-08-2023-0136 | Full text not retrievable |

| El Dine, N. A. A., & Kaoud, M. (2023). Impact of working while studying on university students’ academic performance in Egypt during the COVID-19 pandemic and transition to online learning. Journal of Education and e-Learning Research, 10(4), 627–636. https://doi.org/10.20448/jeelr.v10i4.5018 | Non-psychological focus |

| Epstein, Y. M. (1973). Work-study programs: Do they work? American Journal of Community Psychology, 1(2), 159. | Full text not retrievable |

| Ghant, W. A., Horst, S. J., & Whetstone, D. H. (2016). Portrait of a work-study program assessment. Journal of College Student Development, 57(2), 210–212. https://doi.org/10.1353/csd.2016.0013 | Non-psychological focus |

| Gilmore, D. C., Beehr, T. A., & Richter, D. J. (1979). Effects of leader behaviors on subordinate performance and satisfaction: A laboratory experiment with student employees. Journal of Applied Psychology, 64(2), 166–172. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.64.2.166 | Insufficient population relevance |

| Green, D. L. (1990). High school student employment in social context: Adolescents’ perceptions of the role of part-time work. Adolescence, 25(98), 425. | Non-working-student samples |

| Hall, N. C., Jackson Gradt, S. E., Goetz, T., & Musu-Gillette, L. E. (2011). Attributional retraining, self-esteem, and the job interview: Benefits and risks for college student employment. The Journal of Experimental Education, 79(3), 318–339. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220973.2010.503247 | Non-working-student samples |

| Heilman, J. D. (1939). Student employment and student class load. Journal of Educational Psychology, 30(7), 527–532. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0059447 | Non-working-student samples |

| Hendrix, W. H. (2000). Perceptions of sexual harassment by student-employee classification, marital status, and female racial classification. Journal of Social Behavior & Personality, 15(4), 529–544. | Non-working-student samples |

| Horn, J. R., Trach, J. S., & Haworth, S. L. (1998). Employment outcomes from a collaborative work study program. Journal of Rehabilitation, 64(3), 30. | Full text not retrievable |

| Hovorka-Mead, A. D., Ross, W. H., Jr., Whipple, T., & Renchin, M. B. (2002). Watching the detectives: Seasonal student employee reactions to electronic monitoring with and without advance notification. Personnel Psychology, 55(2), 329–362. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2002.tb00113.x | Insufficient population relevance |

| Howell, W. J. (1953). Concept formation of work-study skills by use of autobiographies in grade four. Journal of Educational Psychology, 44(5), 257–265. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0061813 | Non-working-student samples |

| Jacob, M., Gerth, M., & Weiss, F. (2020). Social inequalities in student employment and the local labour market. KZfSS Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie, 72(1), 55–80. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11577-020-00661-8 | Non-psychological focus |

| Jelsma, J. G., van der Ploeg, H. P., Renaud, L. R., Stijnman, D. P., Loyen, A., Huysmans, M. A., … & van Nassau, F. (2022). Mixed-methods process evaluation of the Dynamic Work study: A multicomponent intervention for office workers to reduce sitting time. Applied Ergonomics, 104, 103823. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apergo.2022.103823 | Non-working-student samples |

| Kara, H. Z., & Kutlu, İ. (2025). Bibliometric analysis of social work studies published in WoS from Turkey. Journal of Evidence-Based Social Work, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/26408066.2025.2541632 | Non-psychological focus |

| Keida, R. (2003). Tips for the working student. Imprint, 50(4), 57–58. | Full text not retrievable |

| Lai, C. J., & Chang, L. Y. (2023). The effects of students’ employment of translation principles and techniques on English-Chinese sight translation performance: An eye-tracking and interview study. Social Sciences & Humanities Open, 8(1), 100542. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssaho.2023.100542 | Non-working-student samples |

| Lang, K. B. (2012). The similarities and differences between working and non-working students at a mid-sized American public university. College Student Journal, 46(2), 243–255. | Non-psychological focus |

| Lavie-Ajayi, M., Ziv, A., Pinson, H., Ram, H., Avieli, N., Zur, E., … & Nimrod, G. (2022). Recreational cannabis use and identity formation: A collective memory work study. World Leisure Journal, 64(4), 325–341. https://doi.org/10.1080/16078055.2022.2043428 | Non-working-student samples |

| Liu, I. F., Hung, H. C., & Liang, C. T. (2024). A study of programming learning perceptions and effectiveness under a blended learning model with live streaming: Comparisons between full-time and working students. Interactive Learning Environments, 32(8), 4396–4410. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2023.2198586 | Non-psychological focus |

| Marklin Jr, R. W., Toll, A. M., Bauman, E. H., Simmins, J. J., LaDisa Jr, J. F., & Cooper, R. (2022). Do head-mounted augmented reality devices affect muscle activity and eye strain of utility workers who do procedural work? Studies of operators and manhole workers. Human Factors, 64(2), 305–323. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018720820943710 | Non-working-student samples |

| Masood, H., Grogan, A., & Chan, C. (2025). How to engage and retain employed students. Career Development International, 30(4), 380–394. https://doi.org/10.1108/CDI-05-2024-0193 | Full text not retrievable |

| Muth, J. W., & Singell, L. D. (1975). Costs and benefits of training educable students: The Kansas Work-Study Project reconsidered. Exceptional Children, 41(5). https://doi.org/10.1177/001440297504100506 | Non-psychological focus |

| Oblova, I. S., & Gerasimova, I. G. (2024). Ensuring equal opportunities in an English-for-specific-purposes course for working-while-studying technical students. Education Sciences, 14(7), 685. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14070685 | Non-psychological focus |

| Owen, M. S., Kavanagh, P. S., & Dollard, M. F. (2018). An integrated model of work-study conflict and work-study facilitation. Journal of Career Development, 45(5), 504–517. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894845317720071 | Non-empirical |

| Pasewark, R. A. (1974). Follow-up study of a summer work study program in mental health and retardation. Journal of Community Psychology, 2(1). https://doi.org/10.1002/1520-6629(197401)2:1<28::AID-JCOP2290020111>3.0.CO;2-7 | Non-working-student samples |

| Payne, J. S., & Chaffin, J. D. (1969). A work-study program after two years of implementation. Journal of Rehabilitation, 35(1), 13. | Full text not retrievable |

| Press, F., Harrison, L., Wong, S., Gibson, M., Cumming, T., & Ryan, S. (2020). The hidden complexity of early childhood educators’ work: The Exemplary Early Childhood Educators at Work study. Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood, 21(2), 172–175. https://doi.org/10.1177/1463949120931986 | Non-working-student samples |

| Różycka-Tran, J., Jurek, P., Olech, M., & Dmochowski, T. (2021). A measurement invariance investigation of the Polish version of the Dual Filial-Piety Scale (DFPS-PL): Student-employee and gender differences in filial beliefs. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 713395. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.713395 | Non-working-student samples |

| Routh, L. A., Chretien, C., & Rakes, T. D. (1995). Career centers and work study employment. Journal of Career Development, 22(2), 125–133. https://doi.org/10.1177/089484539502200206 | Non-empirical |

| Sangganjanavanich, V. F., Lenz, A. S., & Cavazos, J., Jr. (2011). International students’ employment search in the United States: A phenomenological study. Journal of Employment Counseling, 48(1), 17–26. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-1920.2011.tb00107.x | Non-working-student samples |

| Santos, P. R., & Pautassi, R. M. (2023). Association between psychological discomfort and age, sex, work, study, zone of residence in Uruguayan young people. Avances en Psicología Latinoamericana, 41(3). https://doi.org/10.12804/revistas.urosario.edu.co/apl/a.12731 | Non-working-student samples |

| Shulman, A. D., & James, S. A. (1973). Undergraduate community psychology work-study programs: Effects on self-actualization and vocational plans. American Journal of Community Psychology, 1(2), 173. | Full text not retrievable |

| Singleton, W. T. (1972). Total activity analysis: a different approach to work study. Le Travail Humain, 35(2), 241–249. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40660043 | Non-empirical |

| Szabó, Z. P., Kun, Á., Balogh, B. E., Simon, E., & Csike, T. (2022). Dark and strong?! The associations between dark personality traits, mental toughness and resilience in Hungarian student, employee, leader, and military samples. Personality and Individual differences, 186, 111339. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2021.111339 | Non-working-student samples |

| Trueblood, D. L. (1956). Selected characteristics of employed students in the Indiana University School of Business. The Journal of Educational Research, 50(3), 209–213. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220671.1956.10882373 | Non-psychological focus |

| Tsurugano, S., Nishikitani, M., Inoue, M., & Yano, E. (2021). Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on working students: Results from the Labour Force Survey and the student lifestyle survey. Journal of Occupational Health, 63(1), e12209. https://doi.org/10.1002/1348-9585.12209 | Insufficient population relevance |

| Xiao, Y., & Zheng, L. (2025). Can ChatGPT boost students’ employment confidence? A pioneering booster for career readiness. Behavioral Sciences, 15(3), 362. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15030362 | Non-working-student samples |

| Yang, B., Lester, D., & Gatto, J. L. (1989). Working students and their course performance: An extension to high school students. Psychological Reports, 64(1), 218–218. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1989.64.1.218 | Non-working-student samples |

| Wu, Z., Li, S., Chen, Z., & Nie, Y. (2024). An intervention study on college students’ employment anxiety based on interpretation bias modification: A randomized controlled experiment. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 182, 104616. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2024.104616 | Non-working-student samples |

| Wu, W., Zhong, Y., & Zeng, G. (2023). Estimation of peer effect in university students’ employment intentions: Randomization evidence from China. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1241424. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1241424 | Non-working-student samples |

| Zheng, S., Wu, G., Zhao, J., & Chen, W. (2022). Impact of the COVID-19 epidemic anxiety on college students’ employment confidence and employment situation perception in China. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 980634. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.980634 | Non-working-student samples |

| Zhu, J., Lei, L., Wu, P., Cheng, B., Yang, X. L., Fu, J., … & He, F. (2022). The intervention effect of mental health knowledge integrated into ideological and political teaching on college students’ employment and entrepreneurship mentality. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 1002468. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1002468 | Non-working-student samples |

| Zilvinskis, J., & McCormick, A. C. (2019). Do working students buy into HIPs? Working for pay and participation in high-impact practices. Journal of College Student Development, 60(5), 543–562. https://doi.org/10.1353/csd.2019.0049 | Non-psychological focus |

References

- Akos, P., Hutson, B., & Leonard, A. J. (2022a). The relationship between work study and career development for undergraduate students. Journal of Career Development, 49(5), 1097–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akos, P., Leonard, A. J., & Bugno, A. (2021). Federal work-study student perceptions of career readiness. The Career Development Quarterly, 69(1), 78–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akos, P., Leonard, A. J., & Hutson, B. (2022b). Virtual federal work-study and student career development. The Career Development Quarterly, 70(1), 16–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, C. (2018). Professional work load and work-to-school conflict in working-students: The mediating role of psychological detachment from work. Psychology, Society, & Education, 10(2), 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, C., & Fernandes, J. L. (2021). Role boundary management during COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative analysis of focus group data with working-student mothers. Psicologia, 35(1), 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, C., & Fernandes, J. L. (2023). School-family and family-school enrichment: A study with Portuguese working student parents. Education Sciences, 13(10), 1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, C., Fernandes, J. L., & Almeida, L. S. (2024). Mature working student parents navigating multiple roles: A qualitative analysis. Education Sciences, 14(7), 786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aromataris, E., Lockwood, C., Porritt, K., Pilla, B., & Jordan, Z. (2024). JBI manual for evidence synthesis. Available online: https://synthesismanual.jbi.global (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Ashforth, B. E., Kreiner, G. E., & Fugate, M. (2000). All in a day’s work: Boundaries and micro role transitions. Academy of Management Review, 25, 472–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2007). The job demands–resources model: State of the art. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 22(3), 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, L. K., & Santuzzi, A. M. (2017). Telepressure and college student employment: The costs of staying connected across social contexts. Stress and Health, 33(1), 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barone, T. L. (2017). “Sleep is on the back burner”: Working students and sleep. The Social Science Journal, 54(2), 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreto, M. M. S. (2003). Violência, saúde e trabalho: Uma jornada de humilhações. EDUC. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, A. A., Bakker, A. B., & Field, J. G. (2018). Recovery from work-related effort: A meta-analysis. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 39, 262–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaxter, M. (2003). Biology, social class and inequalities in health: Their synthesis in health capital. In S. J. Williams, L. Birke, & G. A. Bendelow (Eds.), Debating biology: Sociological reflections on health, medicine and society (pp. 69–83). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P. (1984). Distinction. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P. (1990). In other words: Essays towards a reflexive sociology. Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P., & Wacquant, L. J. D. (1992). An invitation to reflexive sociology. University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, A. B., Dodge, K. D., & Faurote, E. J. (2010). College student employment and drinking: A daily study of work stressors, alcohol expectancies, and alcohol consumption. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 15(3), 291–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderwood, C., & Gabriel, A. S. (2017). Thriving at school and succeeding at work? A demands-resources view of spillover processes in working students. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 103, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, D. T., & Fiske, D. W. (1959). Convergent and discriminant validation by the multitrait-multimethod matrix. Psychological Bulletin, 56(2), 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceneciro, C. C. (2023). Integrating narratives of working students into higher education curriculum: Equalizer for the socio-economically challenged. Environment and Social Psychology, 8(2), 1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, D. X., & Alcántara, L. (2007). Assessing working students’ college experiences: A grounded theory approach. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 32(3), 301–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, M. L., Conlon, E. G., & Creed, P. A. (2021a). Work–study boundary congruence: Its relationship with student well-being and engagement. International Journal for Educational and Vocational Guidance, 21(1), 81–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, M. L., Creed, P. A., & Conlon, E. G. (2019). Development and initial validation of a work-study congruence scale for university students. International Journal for Educational and Vocational Guidance, 19(2), 257–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, M. L., Creed, P. A., & Conlon, E. G. (2021b). Work–study boundary congruence, contextual supports, and proactivity in university students who work: A moderated-mediation model. Journal of Career Development, 48(2), 166–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creed, P. A., French, J., & Hood, M. (2015). Working while studying at university: The relationship between work benefits and demands and engagement and well-being. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 86, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2013). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. Springer Science & Business Media. [Google Scholar]

- Drăghici, G. L., & Cazan, A. M. (2022). Burnout and maladjustment among employed students. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 825588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubin, R. (1956). Industrial workers’ worlds: A study of the “central life interests” of industrial workers. Social Problems, 3, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubin, R., & Champoux, J. E. (1977). Central life interests and job satisfaction. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 18, 366–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, J. R., & Rothbard, N. P. (2000). Mechanisms linking work and family: Clarifying the relationship between work and family constructs. Academy of Management Review, 25, 178–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, C. M. B., Chavez, J. V., Calibay, R. F., Jr., & Hayudini, M. A. A. (2025). Assessing the utilitarian value of economics and business on personal beliefs and practices among working students. Environment and Social Psychology, 10(5), 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzoi, I. G., D’Ovidio, F., Costa, G., d’Errico, A., & Granieri, A. (2021). Self-rated health and psychological distress among emerging adults in Italy: A comparison between data on university students, young workers and working students collected through the 2005 and 2013 national health surveys. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(12), 6403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frone, M., Russell, M., & Cooper, M. (1992). Antecedents and outcomes of work-family conflict: Testing a model of the work-family interface. Journal of Applied Psychology, 77, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gannon, M. J., Gannon, D. H., & Kaufman, A. (1986). Comparison of student and nonstudent employees. Psychological Reports, 58(1), 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goode, W. J. (1960). A theory of role strain. American Sociological Review, 25, 483–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greeley, J., & Oei, T. (1999). Alcohol and tension reduction. In K. E. Leonard, & H. T. Blake (Eds.), Psychological Theories of Drinking and Alcoholism (2nd ed., pp. 14–53). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Greenhaus, J. H., & Beutell, N. J. (1985). Sources of conflict between work and family roles. Academy of Management Review, 10(1), 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhaus, J. H., & Powell, G. N. (2006). When work and family are allies: A theory of work-family enrichment. Academy of Management Review, 31, 72–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grogan, A., & Lilly, J. (2023). Everything, everywhere, all at once: A study of polychronicity, work-school facilitation, and emotional exhaustion in working students. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 976874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, J. J. (2015). Emotion regulation: Current status and future prospects. Psychological Inquiry, 26(1), 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grozev, V. H., & Easterbrook, M. J. (2022). The relationships of employed students to non-employed students and non-student work colleagues: Identity implications. Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy, 22(2), 712–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grozev, V. H., & Easterbrook, M. J. (2024a). The identities of employed students: Striving to reduce distinctiveness from the typical student. Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy, 24(3), 1252–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grozev, V. H., & Easterbrook, M. J. (2024b). Can social identities improve working students’ academic and social outcomes? Lessons from three studies. Education Sciences, 14(9), 939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halbesleben, J. R. B., Neveu, J.-P., Paustian-Underdahl, S. C., & Westman, M. (2014). Getting to the “COR”: Understanding the role of resources in conservation of resources theory. Journal of Management, 40(5), 1334–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Headrick, L., & Park, Y. A. (2024). How do working students fare? A person-centric approach to understanding patterns of work–school conflict and facilitation. Applied Psychology, 73(2), 648–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J. P. T., Thomas, J., Chandler, J., Cumpston, M., Li, T., Page, M. J., & Welch, V. A. (2023). Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions–Version 6.4. Cochrane. Available online: www.training.cochrane.org/handbook (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Hobfoll, S. E., Freedy, J., Lane, C., & Geller, P. (1990). Conservation of social resources. Journal of Social & Personal Relationships, 7, 465–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S. E., Halbesleben, J., Neveu, J.-P., & Westman, M. (2018). Conservation of resources in the organizational context: The reality of resources and their consequences. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 5(1), 103–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, S. D., Wood, V. R., & Chonko, L. B. (1989). Corporate ethical values and organizational commitment in marketing. Journal of Marketing, 53(3), 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, M., Gerth, M., & Weiss, F. (2020). Social inequalities in student employment and the local labour market. KZfSS Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie, 72(1), 55–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacoby, A. R., & Monteiro, J. K. (2014). Mobbing of working students. Paidéia (Ribeirão Preto), 24(57), 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, E., & Hart, R. (2023). The Outcomes of organizational citizenship behaviors in part-time and temporary working university students. Behavioral Sciences, 13(8), 697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahn, R., Wolfe, D. M., Quinn, R. P., Snoek, J. D., & Rosenthal, R. A. (1964). Organizational stress studies in role conflict and ambiguity. Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Koech, D. K., Degago, E. D., Okore, L. A., & Molnár, E. (2025). Internationalization in higher education: Motives, challenges, support options, and work study balance on WHO-5 wellbeing among international students in Hungary. Acta Psychologica, 258, 105184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreiner, G. E., Hollensbe, E. C., & Sheep, M. L. (2009). Balancing borders and bridges: Negotiating the work-home interface via boundary work tactics. Academy of Management Journal, 52, 704–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefebvre, H. (2013). Rhythmanalysis: Space, time and everyday life. Bloomsbury Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Lenaghan, J. A., & Sengupta, K. (2007). Role conflict, role balance and affect: A model of well-being of the working student. Journal of Behavioral and Applied Management, 9(1), 88–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levac, D., Colquhoun, H., & O’Brien, K. K. (2010). Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implementation Science, 5(1), 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsay, E. K., & Creswell, J. D. (2017). Mechanisms of mindfulness training: Monitor and acceptance theory (MAT). Clinical Psychology Review, 51, 48–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lup, O. L. (2021). How employed students lived the COVID-19 lockdown in Romania. Revista de Cercetare şi Intervenţie Socială, 75, 53–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marks, S. R. (1977). Multiple roles and role strain: Some notes on human energy, time and commitment. American Sociological Review, 42, 921–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C., & Leiter, M. P. (2017). Understanding burnout: New models. In C. L. Cooper, & J. C. Quick (Eds.), The handbook of stress and health (pp. 36–56). John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijman, T. F., & Mulder, G. (1998). Psychological aspects of workload. In P. J. D. Drenth, H. Thierry, & C. de Wolff (Eds.), Handbook of work and organizational psychology, vol. 2: Work psychology (pp. 5–33). Psychology Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munn, Z., Peters, M. D., Stern, C., Tufanaru, C., McArthur, A., & Aromataris, E. (2018). Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 18, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nerona, R. R., Hood, M., Bialocerkowski, A., & Creed, P. A. (2024). Optimistic about the future: How job and study resources facilitate career optimism in working students. Journal of Career Assessment, 33(3), 530–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J. C., & Bernstein, I. H. (1994). Psychometric theory. McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Organ, D. W. (1988). Organizational citizenship behavior: The good soldier syndrome. DC Heath and Com. [Google Scholar]

- Organ, D. W. (1997). Organizational citizenship behavior: It’s construct clean-up time. Human Performance, 10, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, M. S., Kavanagh, P. S., & Dollard, M. F. (2017). An integrated model of work-study conflict and work-study facilitation. Journal of Career Development, 45(5), 504–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., & Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M. D., Godfrey, C. M., Khalil, H., McInerney, P., Parker, D., & Soares, C. B. (2015). Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. JBI Evidence Implementation, 13(3), 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raboca, H. M., & Cărbunărean, F. (2024). Faculty support as part of faculty strategy on the academic motivation of the working students. Education Sciences, 14(7), 746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahayu, A., Fachmi, T., & Burhanudin, M. D. (2024). Exploring student engagement predictors for working students: The role of self-esteem and social support with resilience as mediator. Islamic Guidance and Counseling Journal, 7(2), 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reay, D. (2004). “It’s all becoming a habitus”: Beyond the habitual use of habitus in educational research. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 25(4), 431–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2017). Self-determination theory: Basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness. The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2020). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation from a self-determination theory perspective: Definitions, theory, practices, and future directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 61, 101860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saulius, T., & Malinauskas, R. (2024). Working students’ perceptions of the emotion regulation process. A qualitative study. Current Psychology, 43(12), 10825–10838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulte-Frankenfeld, P. M., & Trautwein, F. M. (2022). App-based mindfulness meditation reduces perceived stress and improves self-regulation in working university students: A randomised controlled trial. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being, 14(4), 1151–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simón, H., Díaz, J. M. C., & Costa, J. L. C. (2017). Analysis of university student employment and its impact on academic performance. Electronic Journal of Research in Educational Psychology, 15(2), 281–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonnentag, S., & Fritz, C. (2007). The recovery experience questionnaire: Development and validation of a measure for assessing recuperation and unwinding from work. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 12, 204–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, R., Murdock, C. D., & Rounds, J. (2015). Person-environment fit. In P. J. Hartung, M. L. Savickas, & W. B. Walsh (Eds.), APA handbook of career intervention (vol. 1, pp. 81–98). American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel, H., Turner, J., Austin, W. G., & Worchel, S. (2001). An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In M. A. Hogg, & D. Abrams (Eds.), Intergroup relations: Essential readings (pp. 94–109). Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, A. (2022). ‘Being there’: Rhythmic diversity and working students. Journal of Education and Work, 35(5), 572–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, W. D., Snyder, L. A., & Lin, L. (2020). What free time? A daily study of work recovery and well-being among working students. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 25(2), 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ten Brummelhuis, L. L., & Bakker, A. B. (2012). A resource perspective on the work–home interface: The work–home resources model. American Psychologist, 67(7), 545–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toyon, M. A. S. (2024). Effect of university social capital on working students’ dropout intentions: Insights from Estonia. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 14(8), 2417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O’Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., Moher, D., Peters, M. D., Horsley, T., Weeks, L., & Hempel, S. (2018). PRISMA extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, J. C., Hogg, M. A., Oakes, P. J., Reicher, S. D., & Wetherell, M. S. (1987). Rediscovering the social group: A self-categorization theory. Basil Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Valentine, S., & Elias, R. Z. (2005). Perceived corporate ethical values and individual cynicism of working students. Psychological Reports, 97(3), 932–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vignoles, V. L. (2011). Identity motives. In S. J. Schwartz, K. Luyckx, & V. L. Vignoles (Eds.), Handbook of identity theory and research (pp. 403–432). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vignoles, V. L., Regalia, C., Manzi, C., Golledge, J., & Scabini, E. (2006). Beyond self-esteem: Influence of multiple motives on identity construction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 90(2), 308–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voydanoff, P. (2008). A conceptual model of the work-family interface. In K. Korabik, D. S. Lero, & D. L. Whitehead (Eds.), Handbook of work-family integration: Research, theory, and best practices (pp. 37–55). Academic Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadsworth, M. (1996). Family and education as determinants of health. In D. Blane, E. Brunner, & R. Wilkinson (Eds.), Health and social organisation (pp. 152–168). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q., Burns, G. N., & Zhang, Y. (2022). Longitudinal tests of stressor–strain relationships among employed students: The role of core self-evaluations. Applied Psychology, 71(1), 197–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, J. R., Masuda, Y. J., & Tallis, H. (2016). A measure whose time has come: Formalizing time poverty. Social Indicators Research, 128(1), 265–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C., Wang, X., & Zou, Y. (2023). Exploration of college students’ psychological problems based on online education under COVID-19. Psychology in the Schools, 60(10), 3716–3737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziskin, M., Fischer, M. A., Torres, V., Pellicciotti, B., & Player-Sanders, J. (2014). Working students’ perceptions of paying for college: Understanding the connections between financial aid and work. The Review of Higher Education, 37(4), 429–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Bibliographical Source | Search Query |

|---|---|

| EBSCOhost | TI 1 (“working students” or “working student” or “employed student” or “employed students”) OR TI (“student workers” or “student employees”) AND TI “working undergraduates” AND TI (“student employment” or “work study” or “student worker”) AND TI “working while attending college” AND TI “working while studying” AND TI “working university students” AND TI “employed college students” AND TI “students with jobs” Search mode: Find all my search terms Expanders: Apply related words; Apply equivalent subjects Filters: Peer Reviewed Interface: EBSCOhost Research Databases Databases: APA PsycInfo, MEDLINE, Psychology and Behavioral Sciences Collection, APA PsycArticles |

| Scopus | TITLE (“working students”) OR TITLE (“working student”) OR TITLE (“employed student”) OR TITLE (“employed students”) OR TITLE (“student workers”) OR TITLE (“student employees”) OR TITLE (“working undergraduates”) OR TITLE (“student employment”) OR TITLE (“work study”) OR TITLE (“student worker”) OR TITLE (“working while attending college”) OR TITLE (“working while studying”) OR TITLE (“working university students”) OR TITLE (“employed college students”) OR TITLE (“students with jobs”) AND (LIMIT-TO (SUBJAREA,”PSYC”)) AND (LANGUAGE,” English”)) |

| Web of Science | (TI = (“working students”) OR TI = (“working student”) OR TI = (“employed student”) OR TI = (“employed students”) OR TI = (“student workers”) OR TI = (“student employees”) OR TI = (“working undergraduates”) OR TI = (“student employment”) OR TI = (“work study”) OR TI = (“student worker”) OR TI = (“working while attending college”) OR TI = (“working while studying”) OR TI = (“working university students”) OR TI = (“employed college students”) OR TI = (“students with jobs”)) AND (DT 2 = (“ARTICLE” OR “REVIEW”) AND TASCA = (“PSYCHOLOGY APPLIED” OR “PSYCHOLOGY” OR “PSYCHOLOGY SOCIAL” OR “PSYCHOLOGY MULTIDISCIPLINARY” OR “PSYCHOLOGY EDUCATIONAL” OR “PSYCHOLOGY BIOLOGICAL” OR “PSYCHOLOGY CLINICAL” OR “PSYCHOLOGY DEVELOPMENTAL” OR “PSYCHOLOGY EXPERIMENTAL”) AND LA 3 = (“ENGLISH”)) |

| Author(s) and Year | Country | n 1 | Theoretical Framework | Methods | Design |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Akos et al., 2021) | USA | 1752 | Career readiness scholarship | Quantitative | Cross-sectional |

| (Akos et al., 2022a) | USA | 549 | Career readiness scholarship | Quantitative | Cross-sectional |

| (Akos et al., 2022b) | USA | 562 | Career readiness scholarship | Quantitative | Longitudinal |

| (Andrade, 2018) | Portugal | 152 | Role conflict and facilitation theory; Psychological detachment from work scholarship | Quantitative | Cross-sectional |

| (Andrade & Fernandes, 2021) | Portugal | 8 | Role boundary theory | Qualitative | Cross-sectional |

| (Andrade & Fernandes, 2023) | Portugal | 155 | School–family interaction model | Quantitative | Cross-sectional |

| (Andrade et al., 2024) | Portugal | 11 | Role boundary theory | Qualitative | Cross-sectional |

| (Barber & Santuzzi, 2017) | USA | 241 | Telepressure scholarship | Quantitative | Cross-sectional |

| (Barone, 2017) | USA | 19 | Health capital concept | Qualitative | Cross-sectional |

| (Butler et al., 2010) | USA | 106 | Tension reduction theory | Quantitative | Longitudinal |

| (Calderwood & Gabriel, 2017) | USA | 188 | Job demands–resources; Work–home resources | Quantitative | Longitudinal |

| (Ceneciro, 2023) | Philippines | 12 | Rhythmanalysis | Qualitative | Cross-sectional |

| (Cheng & Alcántara, 2007) | USA | 14 | Grounded theory | Qualitative | Cross-sectional |

| (Chu et al., 2019) | Australia | 255 | Role boundary theory; Test theory | Mixed | Cross-sectional |

| (Chu et al., 2021a) | Australia | 251 | Role boundary theory | Quantitative | Cross-sectional |

| (Chu et al., 2021b) | Australia | 401 | Role boundary theory; Person–environment fit; Conservation of resources | Quantitative | Cross-sectional |

| (Creed et al., 2015) | Australia | 185 | Role conflict and facilitation theory | Quantitative | Cross-sectional |

| (Drăghici & Cazan, 2022) | Romania | 151 | Burnout three–dimensional model | Quantitative | Cross-sectional |

| (Fernandez et al., 2025) | Philippines | 40 | Utilitarian value scholarship | Qualitative | Cross-sectional |

| (Franzoi et al., 2021) | Italy | 18,612 | Health and psychological distress scholarship | Quantitative | Cross-sectional |

| (Gannon et al., 1986) | USA | 325 | Student employees scholarship | Quantitative | Cross-sectional |

| (Grogan & Lilly, 2023) | USA | 153 | Conservation of resources, Enrichment theory | Quantitative | Longitudinal |

| (Grozev & Easterbrook, 2022) | UK | 21 | Social identity approach | Qualitative | Cross-sectional |

| (Grozev & Easterbrook, 2024a) | UK | 215 | Social identity approach; Motivated identity construction theory | Mixed | Cross-sectional |

| (Grozev & Easterbrook, 2024b) | UK | 129 | Social identity approach | Quantitative | Cross-sectional |

| (Headrick & Park, 2024) | USA | 347 | Role scarcity hypothesis; Role expansion hypothesis; Segregation hypothesis | Quantitative | Longitudinal |

| (Jacoby & Monteiro, 2014) | Brazil | 457 | Workplace violence scholarship; Mobbing scholarship | Quantitative | Cross-sectional |

| (Johansson & Hart, 2023) | UK | 122 | Organizational citizenship behavior scholarship | Quantitative | Cross-sectional |

| (Koech et al., 2025) | Hungary | 125 | Work–study life balance scholarship | Quantitative | Cross-sectional |

| (Lenaghan & Sengupta, 2007) | USA | 320 | Depletion argument; Enrichment argument | Quantitative | Cross-sectional |

| (Lup, 2021) | Romania | 2026 | Time poverty framework | Mixed | Cross-sectional |

| (Nerona et al., 2024) | Australia | 256 | Conservation of resources; Self-determination theory | Quantitative | Longitudinal |

| (Raboca & Cărbunărean, 2024) | Romania | 137 | Self-determination theory | Quantitative | Cross-sectional |

| (Rahayu et al., 2024) | Indonesia | 340 | Student engagement scholarship | Quantitative | Cross-sectional |

| (Saulius & Malinauskas, 2024) | Lithuania | 18 | Gross’s process model of emotion regulation | Qualitative | Longitudinal |

| (Schulte-Frankenfeld & Trautwein, 2022) | Netherlands | 64 | Active mechanisms of mindfulness-based interventions | Quantitative | Longitudinal |

| (Simón et al., 2017) | Spain | 464 | Academic achievement scholarship | Quantitative | Longitudinal |

| (W. D. Taylor et al., 2020) | USA | 268 | Work recovery theory | Quantitative | Longitudinal |

| (Toyon, 2024) | Estonia | 1902 | University social capital model | Quantitative | Cross-sectional |

| (Valentine & Elias, 2005) | USA | 195 | Corporate ethical values scholarship | Quantitative | Cross-sectional |

| (Wang et al., 2022) | USA | 147 | Conservation of resources | Quantitative | Longitudinal |

| (Ziskin et al., 2014) | USA | 114 | Social reproduction | Qualitative | Cross-sectional |

| Appraised Study | Q 11 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 | Q8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Akos et al., 2021) | UNCLEAR | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO | YES |

| (Akos et al., 2022a) | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| (Akos et al., 2022b) | YES | YES | YES | UNCLEAR | NO | YES | YES | YES |

| (Andrade, 2018) | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| (Andrade & Fernandes, 2023) | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| (Barber & Santuzzi, 2017) | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| (Butler et al., 2010) | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| (Calderwood & Gabriel, 2017) | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| (Chu et al., 2019) | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| (Chu et al., 2021a) | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| (Chu et al., 2021b) | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| (Creed et al., 2015) | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| (Drăghici & Cazan, 2022) | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| (Franzoi et al., 2021) | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| (Gannon et al., 1986) | YES | YES | UNCLEAR | NO | NO | NO | UNCLEAR | YES |

| (Grogan & Lilly, 2023) | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| (Grozev & Easterbrook, 2024a) | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| (Grozev & Easterbrook, 2024b) | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| (Headrick & Park, 2024) | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| (Jacoby & Monteiro, 2014) | YES | YES | YES | YES | UNCLEAR | NO | YES | YES |

| (Johansson & Hart, 2023) | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| (Koech et al., 2025) | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| (Lenaghan & Sengupta, 2007) | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| (Lup, 2021) | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| (Nerona et al., 2024) | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| (Raboca & Cărbunărean, 2024) | YES | YES | YES | YES | NO | NO | YES | YES |

| (Rahayu et al., 2024) | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| (Schulte-Frankenfeld & Trautwein, 2022) | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| (Simón et al., 2017) | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| (W. D. Taylor et al., 2020) | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| (Toyon, 2024) | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| (Valentine & Elias, 2005) | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| (Wang et al., 2022) | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Appraised Study | Q 11 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 | Q8 | Q9 | Q10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Andrade & Fernandes, 2021) | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| (Andrade et al., 2024) | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| (Barone, 2017) | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | UNCLEAR | UNCLEAR | YES | YES | YES |

| (Ceneciro, 2023) | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | UNCLEAR | UNCLEAR | YES | YES | YES |

| (Cheng & Alcántara, 2007) | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| (Chu et al., 2019) | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| (Fernandez et al., 2025) | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| (Grozev & Easterbrook, 2022) | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| (Grozev & Easterbrook, 2024a) | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| (Lup, 2021) | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| (Saulius & Malinauskas, 2024) | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| (Ziskin et al., 2014) | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

di Biase, G.; Giusino, D. The Psychology of Working Students: A Scoping Review. Psychol. Int. 2026, 8, 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/psycholint8010011

di Biase G, Giusino D. The Psychology of Working Students: A Scoping Review. Psychology International. 2026; 8(1):11. https://doi.org/10.3390/psycholint8010011

Chicago/Turabian Styledi Biase, Gaetana, and Davide Giusino. 2026. "The Psychology of Working Students: A Scoping Review" Psychology International 8, no. 1: 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/psycholint8010011

APA Styledi Biase, G., & Giusino, D. (2026). The Psychology of Working Students: A Scoping Review. Psychology International, 8(1), 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/psycholint8010011