1. Introduction

Positive Psychology has emerged as a rapidly growing subdiscipline within the broader field of psychology, shifting the scientific focus from the remediation of pathology to the cultivation of well-being and human potential. In 1998, Martin Seligman—then-president of the American Psychological Association—called for a new scientific paradigm that emphasised human strengths, positive emotions, meaning-making, and virtues, proposing a reorientation from the predominant focus on dysfunction toward what enables individuals and communities to thrive (

Levin, 2020;

Ryff, 2022;

Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000). Within this context, Positive Psychology aims to explore the personal and social variables that contribute to psychological flourishing, resilience, and well-being (

De la Fuente et al., 2022;

Gable & Haidt, 2005).

Among the constructs gaining increasing empirical attention is self-compassion, an attitude of kindness, care, and understanding toward oneself in times of difficulty, failure, or suffering (

Neff, 2003a). Rather than avoiding pain or succumbing to self-criticism, individuals high in self-compassion engage with their suffering in a balanced and mindful way, recognising their experiences as part of the shared human condition. This orientation enables emotional regulation and supports adaptive coping strategies, particularly in stressful or adverse circumstances (

Tiwari et al., 2020;

Inwood & Ferrari, 2018).

It is important to distinguish between trait and state self-compassion. Trait self-compassion refers to a relatively stable tendency to respond to personal suffering with kindness and mindfulness across time and situations. In contrast, state self-compassion (SSCS) reflects a momentary, context-dependent experience of being kind and understanding toward oneself in a specific situation (

Neff et al., 2021). The present study focuses on state self-compassion, capturing participants’ current compassionate attitudes toward themselves rather than their general disposition.

A growing body of research has demonstrated the benefits of self-compassion for psychological health. It has been associated with greater emotional resilience (

Austin et al., 2023), enhanced well-being (

Cowand et al., 2024;

Stapleton et al., 2018), and lower levels of psychopathology, including anxiety, depression, and stress symptoms (

MacBeth & Gumley, 2012;

Smith, 2023). Additionally, interventions designed to cultivate self-compassion have shown promising outcomes across clinical and non-clinical populations (

Ferrari et al., 2019;

E. Beaumont et al., 2025), further validating its role as a protective and promotive factor for mental health.

More recently, researchers have begun investigating developmental variations in self-compassion across the lifespan. While some studies suggest that self-compassion may increase with age due to emotional maturation and life experience (

Homan, 2016;

Stapleton et al., 2018), others report no significant associations between age and self-compassion levels (

Phillips & Ferguson, 2013;

Tavares et al., 2024). Given these mixed findings, further exploration is needed to determine whether age moderates the protective effect of SSCS on mental health outcomes. To address this gap, the present study examines the relationship between SSCS and symptoms of anxiety and depression in different adult age groups. Drawing from Positive Psychology and Counselling Psychology frameworks, the study explores (a) the associations among SSCS, age, anxiety, and depression; symptoms, (b) the protective role of SSCS and age in association with anxiety and depression symptoms; and (c) potential interaction effects between age groups and SSCS levels. By exploring SSCS across different stages of adulthood, this study helps us better understand how it operates throughout adulthood. Moreover, it provides empirical evidence that can inform the design of age-appropriate intervention programs that integrate SSCS training to support adult mental health and psychological well-being.

1.1. The Conceptual Framework of Self-Compassion

Rooted in Buddhist philosophy, self-compassion encompasses kindness and understanding toward oneself in times of difficulty, recognising one’s experiences as part of the shared human condition (

Neff, 2003a,

2003b). It involves three interrelated components: self-kindness (vs. self-judgment), common humanity (vs. isolation), and mindfulness (vs. over-identification). These elements jointly foster emotional balance and adaptive coping (

Bishop et al., 2004;

Gilbert & Irons, 2004;

Neff, 2009). Research consistently links higher self-compassion with improved psychological well-being and lower symptoms of anxiety, depression, and stress (

MacBeth & Gumley, 2012;

Stapleton et al., 2018;

Querstret et al., 2020).

Building on this conceptual foundation, it is essential to distinguish self-compassion from other related constructs to clarify its unique psychological function. Self-compassion differs from self-esteem or self-pity in that it does not depend on self-evaluation or the avoidance of pain, but rather on acceptance and mindful awareness (

Neff, 2003a). Positive dimensions, such as self-kindness and mindfulness, are associated with resilience and emotional stability, whereas negative dimensions, including self-criticism, are associated with psychological distress (

Stapleton et al., 2018). In both clinical and non-clinical populations, higher self-compassion is associated with greater well-being and lower psychopathology (

Bluth et al., 2018;

Cowand et al., 2024;

Nery-Hurwit et al., 2018).

Having outlined the conceptual dimensions of self-compassion and its distinction from related constructs, it is also important to clarify how this construct can be experienced and measured over time. Self-compassion can be conceptualised as either a trait, reflecting a stable disposition to respond to suffering kindly and mindfully across contexts, or a state, representing a momentary compassionate self-attitude toward oneself within a specific situation (

Neff et al., 2021). Trait self-compassion is typically assessed using the Self-Compassion Scale (SCS;

Neff, 2003a,

2003b), which measures the enduring tendency to respond with greater self-kindness, mindfulness, and common humanity, and with reduced self-judgment, isolation, and over-identification across various situations. The SCS has been validated across cultures and populations, confirming its robustness as a measure of global self-compassion as a stable personality characteristic.

In contrast, state self-compassion captures momentary, situational fluctuations in compassionate self-responding—how individuals treat themselves in a specific instance of suffering. It reflects the mindstate of state self-compassion as it occurs in real time, rather than a generalised tendency across situations. To measure this construct,

Neff et al. (

2021) developed the State Self-Compassion Scale-ong Form (SSCS-L) and the Short Form (SSCS-S). The SSCS-L includes 18 items assessing the six components of state self-compassion (self-kindness, common humanity, mindfulness, reduced self-judgment, isolation, and over-identification), while the SSCS-S is a six-item proxy for global state self-compassion. Both scales demonstrated excellent psychometric validity and sensitivity to experimental changes in state self-compassion following a self-compassionate mindstate induction. The present study employs the SSCS-L to assess individuals’ momentary self-compassion, providing a nuanced understanding of compassionate self-responding among Greek adults within specific contexts of emotional difficulty.

1.2. Self-Compassion and Age: A Developmental Perspective

While the association between self-compassion and mental health is well documented, findings on age-related variations in self-compassion remain inconsistent. Some studies report no significant variation across age groups (

Neff & McGehee, 2010;

Phillips & Ferguson, 2013), while others suggest that self-compassion increases with age, potentially due to greater life experience, emotional regulation, and identity maturity (

Homan, 2016;

Stapleton et al., 2018;

Bratt & Fagerström, 2020). Theoretically,

Erikson’s (

1968) stage of ego integrity suggests that later adulthood fosters greater self-acceptance and compassion. Moreover, older adults tend to exhibit increased mindfulness and reduced self-criticism, central components of self-compassion (

Lee et al., 2021). Consistent with this view, Greek studies have shown that adults over 50 display lower levels of over-identification and greater mindfulness (

Karakasidou et al., 2020).

Murn and Steele (

2019) reported that older participants showed higher levels of mindfulness and common humanity. Nonetheless, discrepancies in literature call for further investigation into whether and how age interacts with state self-compassion to influence mental health outcomes.

A robust body of research demonstrates that higher self-compassion is associated with lower symptoms of anxiety and depression across diverse populations (

de Souza et al., 2020;

Callow et al., 2021). Self-compassion mitigates the impact of shame and self-criticism on depressive and anxious symptoms (

H. Zhang et al., 2019) and is linked to enhanced resilience (

Baker et al., 2019). Studies in clinical samples—including patients with chronic illnesses and mental-health challenges—support its role as a protective factor (

Trindade & Sirois, 2021;

Alsamman et al., 2024).

Zhu et al. (

2019) found that cancer patients with higher self-compassion shortly after diagnosis experienced fewer depressive and anxious symptoms during treatment and better long-term functioning.

Baker et al. (

2019) reported similar findings in adults with epilepsy, where self-compassion predicted lower depression and anxiety symptoms and greater resilience.

López et al. (

2018) linked self-coldness and isolation to higher depressive symptoms in the Dutch population. In Greek contexts, self-compassion has been associated with reduced anxiety and depressive symptoms, and greater well-being among adults and students (

Karakasidou et al., 2023).

Moreover, self-compassion has been found to correlate positively with perceived social support (

Aulia & Fitriani, 2024), with both variables acting as significant joint predictors of well-being (

Hermanoes et al., 2024). It also mediates the relationship between perceived social support—particularly from family and significant others—and subjective well-being among members of the lesbian, gay, and bisexual community (

Toplu-Demirtaş et al., 2018). Higher self-compassion is linked to greater life satisfaction (

Singh & Singh Johal, 2024) and negatively associated with boredom, mediated by the meaning individuals ascribe to life experiences (

O’Dea et al., 2022). It also predicts subjective authenticity, partly explained by greater optimism and reduced fear of negative evaluation by others (

J. W. Zhang et al., 2019). Additionally, self-compassion is negatively correlated with anxious and avoidant attachment in adulthood, with its positive aspects inversely related to these attachment styles (

Huang & Wu, 2025). It is also associated with higher-quality romantic relationships and predicts relationship satisfaction, particularly in early marriage (

Jacobson et al., 2018;

Fahimdanesh et al., 2020).

Self-compassion extends beyond personal well-being; it is associated with pro-environmental behaviours through increased nature-connectedness (

Ballarotto et al., 2025) and with higher creative productivity, thereby mediating the link between artistic achievement and lower emotional dysregulation (

Verger et al., 2022). Compared with the general population, individuals diagnosed with mental disorders tend to exhibit lower self-compassion, which, in combination with psychopathological symptoms, further exacerbates their mental health difficulties (

Athanasakou et al., 2020). Self-compassion has been shown to reduce symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (

Winders et al., 2020), and it is negatively associated with suicidal ideation and self-harm behaviours (

Cleare et al., 2019). Furthermore, it has been linked to lower disordered eating and body image concerns (

Turk & Waller, 2020). It has been identified as a contributing factor to recovery from a broad range of substance use disorders (

Chen, 2019). In light of these findings, understanding how momentary (state) experiences of self-compassion relate to psychological distress across different adult life stages may provide valuable insights for mental health prevention and intervention. While previous research has mainly focused on trait self-compassion, this study extends the literature by exploring the protective role of state self-compassion across adulthood within the Greek population. To address these gaps, the present study investigated the protective role of state self-compassion in relation to anxiety and depression symptoms across different adult age groups in the Greek population. Specifically, we examined whether higher state self-compassion predicts lower psychological distress and whether this association varies by age. Based on prior literature, we expected that higher self-compassion would be significantly associated with fewer symptoms of depression and anxiety across all age groups.

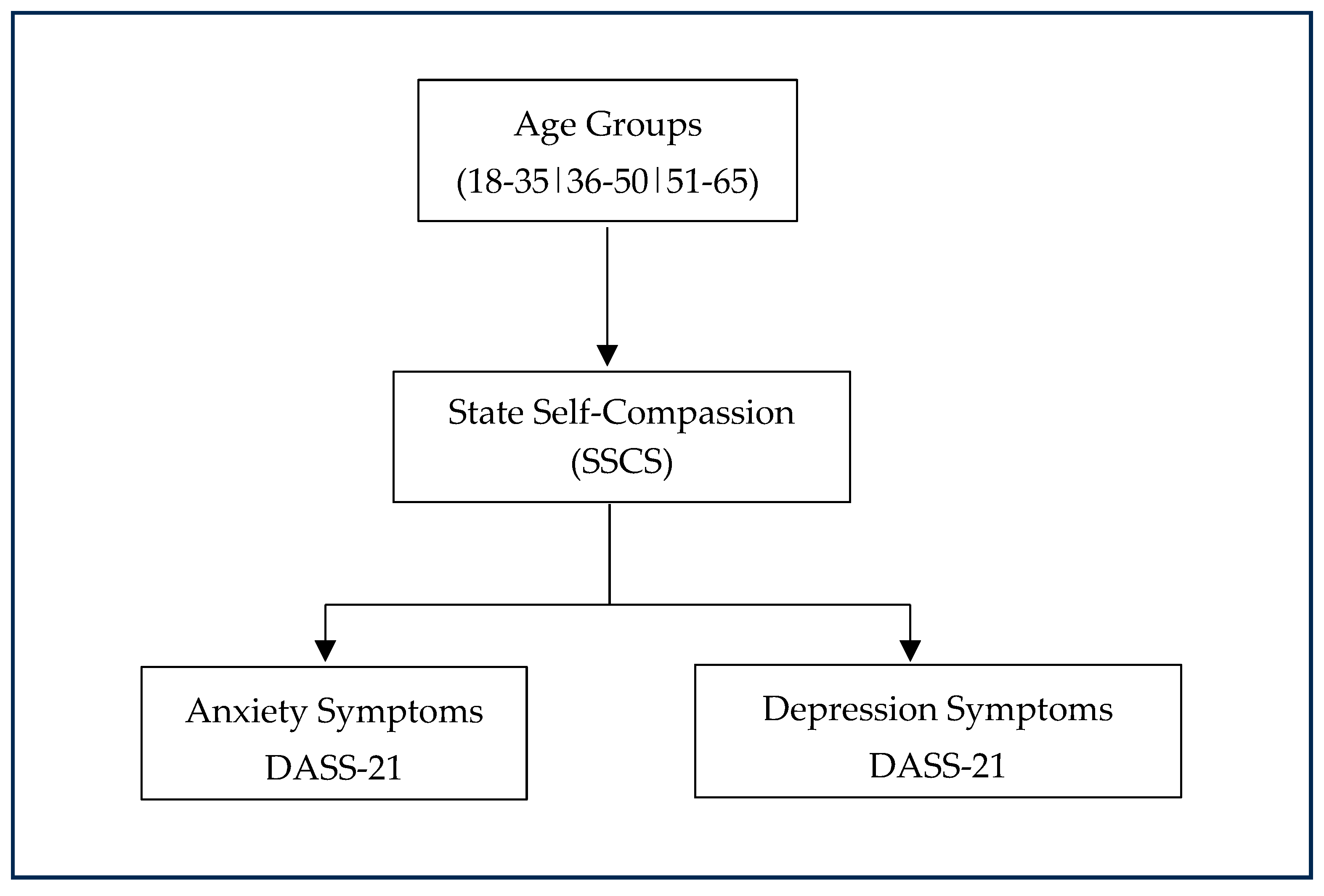

Building on the above theoretical and empirical evidence, the present study aims to examine the protective role of SSCS in relation to depression and anxiety symptoms across a wide range of adult age groups. Specifically, it seeks to:

Explore the associations among SSCS, age, anxiety, and depression symptoms.

Determine whether SSCS and age are significantly related to symptoms of anxiety and depression.

Investigate whether there are interaction effects between age groups and SSCS levels on anxiety and depression symptoms.

Prior research has shown self-compassion as a protective factor for lowering depressive and anxious symptoms in both general and clinical populations (

Alsamman et al., 2024;

Baker et al., 2019;

Callow et al., 2021;

de Souza et al., 2020;

Karakasidou et al., 2023;

Trindade & Sirois, 2021;

H. Zhang et al., 2019;

Zhu et al., 2019). However, findings about the relationship between self-compassion and age remain mixed. Some studies indicate self-compassion increases with age (

Bratt & Fagerström, 2020;

Homan, 2016;

Karakasidou et al., 2020;

Lee et al., 2021;

Murn & Steele, 2019;

Stapleton et al., 2018), while others find no significant age-related differences (

Neff & McGehee, 2010;

Neff & Pommier, 2013;

Phillips & Ferguson, 2013;

Tavares et al., 2024). This calls for further investigation into the link between age and self-compassion. Additionally, there is a research gap regarding the protective ability of SSCS in association with depression and anxiety symptoms throughout adult life. This study is important for understanding how SSCS influences depression and anxiety symptoms at different adult stages, supporting the design of age-appropriate interventions.

The hypotheses are:

H1. Higher levels of state self-compassion are negatively associated with symptoms of anxiety and depression across adults.

H2. There is an interaction effect between state self-compassion levels (low, moderate, high) and age groups (18–35 years, 36–50 years, 51–65 years) on anxiety and depression symptoms, such that the protective association of self-compassion is stronger among older adults.

H3. State self-compassion and age are significantly associated with anxiety and depression symptoms, such that higher state self-compassion and older age will be related to lower levels of anxiety and depression.

H4. Age moderates the relationship between state self-compassion and symptoms of anxiety and depression, such that the negative association between self-compassion and psychological symptoms is stronger among older adults.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

Preliminary analyses were conducted to examine the distributions and relationships among state self-compassion (SSCS), age, depression, and anxiety symptoms. Descriptive statistics are presented in

Table 3. Participants’ state self-compassion scores were moderate overall (

M = 3.29,

SD = 0.66, range = 1–5). Mean depression and anxiety symptoms scores were

M = 11.20 (

SD = 10.14, range = 0–42) and

M = 8.81 (

SD = 9.04, range = 0–42), respectively, while participants’ ages ranged from 18 to 65 years (

M = 41.49,

SD = 13.55) (N = 1528).

3.2. Correlational Analyses

Normality, linearity, and outliers were evaluated prior to correlation analyses. Visual inspection of histograms and Q–Q plots indicated approximate normality for SSCS and age, with moderate positive skew for depression and anxiety. Significant Shapiro–Wilk tests (p < 0.001) were expected given the large sample size. Scatterplots revealed linear, monotonic relationships and no extreme outliers.

As shown in

Table 4, higher state self-compassion was strongly and negatively correlated with both depression symptoms (ρ = −0.65,

p < 0.001) and anxiety symptoms (ρ = −0.52,

p < 0.001), indicating that greater self-compassion was associated with fewer symptoms of psychological distress. According to Cohen’s guidelines (|r| ≈ 0.50 = large), these represent large effect sizes, suggesting that individuals with higher self-compassion tend to report substantially fewer symptoms of psychological distress. Age was positively associated with self-compassion (ρ = 0.14,

p < 0.001) and negatively associated with both depression (ρ = −0.10,

p < 0.001) and anxiety (ρ = −0.12,

p < 0.001) symptoms. These are small effect sizes, indicating that older individuals reported slightly higher self-compassion and marginally lower distress levels. Depression and anxiety symptoms were highly intercorrelated (ρ = 0.68,

p < 0.001), representing a large effect size and suggesting that these forms of psychological distress share substantial overlap.

3.3. Two-Way ANOVA Analyses

A 3 (Self-Compassion: Low, Moderate, High) × 3 (Age Group: 18–35, 36–50, 51–65) between-subjects ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of self-compassion,

F(2, 1519) = 191.45,

p < 0.001, η

2p = 0.20, representing a large effect (

Cohen, 1988). Anxiety symptoms decreased steadily with higher self-compassion: low (M = 17.56, SD = 9.92), moderate (M = 10.06, SD = 8.88), and high (M = 4.33, SD = 5.90). This large effect indicates a substantial and practically meaningful reduction in anxiety among individuals with higher self-compassion.

A small main effect of age emerged, F(2, 1519) = 3.89, p = 0.021, η2p = 0.005, indicating slightly higher anxiety symptoms among younger adults (18–35: M = 11.57; 36–50: M = 10.02; 51–65: M = 10.24). Although statistically significant, the effect size is small, indicating that age contributed minimally to anxiety differences.

The interaction between self-compassion and age was not significant, F(4, 1519) = 1.04, p = 0.385, suggesting that self-compassion was associated with lower anxiety symptoms at all age levels, and no interaction was found between age and self-compassion.

Because Levene’s test was significant, a Welch’s ANOVA was performed as a robustness check. Results were identical, F(2, 451.32) = 202.29, p < 0.001, confirming the strong effect of SSCS on anxiety symptoms. Games–Howell post hoc tests showed that all pairwise differences between self-compassion levels were significant (ps < 0.001).

Overall, higher SSCS was strongly and consistently associated with lower anxiety symptoms across all age groups (

Table 5).

A 3 (Self-Compassion: Low, Moderate, High) × 3 (Age Group: 18–35, 36–50, 51–65) between-subjects ANOVA showed a significant main effect of self-compassion,

F(2, 1519) = 376.93,

p < 0.001, η

2p = 0.332, with depression symptoms scores decreasing as self-compassion increased, indicating a large effect size (

Cohen, 1988). Depression symptoms decreased markedly as self-compassion increased: participants with low self-compassion (

M = 23.84,

SD = 10.19) reported significantly higher depression symptoms than those with moderate (

M = 12.91,

SD = 9.19) or high state self-compassion (

M = 4.86,

SD = 5.90),

ps < 0.001. This large η

2p value (0.33) suggests that one-third of the variance in depression scores was explained by self-compassion levels—a substantial and practically meaningful effect.

The main effect of age was not significant, F(2, 1519) = 1.12, p = 0.328, and the interaction between age and self-compassion was also non-significant, F(4, 1519) = 1.88, p = 0.112, indicating that differences in depression scores across self-compassion levels were similar across age groups.

To verify robustness, a Welch’s ANOVA was also performed and yielded consistent results,

F(2, 449.97) = 393.28,

p < 0.001, η

2 = 0.33. Games–Howell post hoc tests confirmed that participants with low self-compassion reported significantly higher depression symptoms than those with moderate or high state self-compassion, and moderate levels were also higher than high levels (

ps < 0.001). The effect was large, supporting a strong inverse association between state self-compassion and depressive symptoms (

Table 6).

3.4. Multiple Regression Analyses

Regression assumptions were verified. Multicollinearity was absent (VIF ≈ 1.02). Residuals were approximately normal, and scatterplots confirmed homoscedasticity. No influential outliers were detected (Cook’s D < 1).

Two hierarchical multiple regression analyses were conducted to test whether state self-compassion and age predicted anxiety and depression symptom scores. For depression symptoms, the model was significant,

F(2, 1525) = 1062.46,

p < 0.001, explaining 41.7% of the variance (R

2 = 0.42). According to

Cohen (

1988), this represents a large effect size, indicating that the predictors accounted for a substantial proportion of the variability in depression scores. Self-compassion significantly predicted lower depression symptoms (β = −9.90,

p < 0.001), representing a large effect. In contrast, age did not (β = −0.01,

p = 0.62 *), reflecting a negligible effect size and indicating that age did not meaningfully contribute to depression symptom levels when self-compassion was considered. Results are presented in

Table 7.

For anxiety symptoms, the model was also significant,

F(2, 1525) = 470.59,

p < 0.001, accounting for 24.8% of the variance (R

2 = 0.25). This constitutes a large effect size (

Cohen, 1988), indicating that the predictors collectively explained about one-quarter of the variance in anxiety symptoms. Self-compassion again emerged as a strong and significant negative predictor of anxiety (β = −0.49,

p < 0.001), indicating a large effect size and demonstrating that individuals with greater self-compassion reported substantially lower anxiety symptoms. Age was also a significant but weak negative predictor (β = −0.07,

p = 0.009), representing a small effect size. Thus, while older age was associated with slightly lower anxiety, the impact was minimal compared to self-compassion.

3.5. Moderation Analyses

A moderation analysis was performed using Hayes’ PROCESS macro (Model 1;

Hayes, 2018) in SPSS to examine whether age moderated the relationship between state self-compassion and depression symptoms. The overall model was significant, F(3, 1524) = 364.37,

p < 0.001, explaining 41.8% of the variance in depression (R

2 = 0.42). State self-compassion was a strong negative predictor of depression (b = −9.93, SE = 0.30, β = −0.65, t(1524) = −32.64,

p < 0.001), whereas age was not a significant predictor (b = −0.01, SE = 0.02, β = −0.01, t(1524) = −0.44,

p = 0.66). The interaction between age and self-compassion was not significant (b = 0.04, SE = 0.02, β = 0.03, t(1524) = 1.63,

p = 0.10), indicating that age did not moderate the association between self-compassion and depression symptoms. Simple-slope analyses showed that the negative relationship between self-compassion and depression was significant at low (−1 SD; b = −10.45,

p < 0.001), average (b = −9.93,

p < 0.001), and high (+1 SD; b = −9.42,

p < 0.001) levels of age. These results confirm that self-compassion predicts lower depression consistently across adulthood.

A moderation analysis using Hayes’ PROCESS macro (Model 1;

Hayes, 2018) in SPSS was conducted to examine whether age moderated the relationship between state self-compassion and anxiety symptoms. The overall model was significant, F(3, 1524) = 168.74,

p < 0.001, explaining 24.9% of the variance in anxiety (R

2 = 0.25). State self-compassion was a strong negative predictor of anxiety (b = −6.70, SE = 0.31, β = −0.49, t(1524) = −21.75,

p < 0.001), and age also significantly predicted lower anxiety levels (b = −0.04, SE = 0.02, β = −0.06, t(1524) = −2.57,

p = 0.010). However, the interaction between age and self-compassion was not significant (b = 0.03, SE = 0.02, β = 0.03, t(1524) = 1.43,

p = 0.15), indicating that age did not moderate the association between self-compassion and anxiety symptoms. These results suggest that self-compassion predicts lower anxiety across adulthood, independent of age as shown in

Table 8.

4. Discussion

The present study contributes to the growing body of research on state self-compassion by examining its role across different age groups. This area has received relatively limited empirical attention to date. Understanding how self-compassion relates to psychological well-being across the lifespan is particularly timely, given the growing interest in resilience and mental health promotion across diverse age cohorts. The study tested four hypotheses: (H1) that higher levels of self-compassion would be associated with lower symptoms of anxiety and depression; (H2) that the protective association between self-compassion and symptoms would vary across age groups; (H3) that higher self-compassion and older age would jointly predict lower anxiety and depression symptoms; and (H4) that age would moderate the relationship between self-compassion and psychological symptoms. Results supported H1 and partially supported H3, whereas H2 was not supported, indicating that self-compassion was strongly and consistently related to lower psychological distress across all age groups. H4 were not supported. Both the ANOVA models and the PROCESS analyses consistently indicated that the association between self-compassion and symptoms did not vary by age, providing convergent evidence that no moderation occurred. The PROCESS moderation models did not reveal significant interactions between age and state self-compassion. These findings indicate that the protective association between self-compassion and psychological distress remains stable across adulthood, rather than varying by age group or being contingent upon age as a moderating factor.

The results revealed a statistically significant positive correlation between age and self-compassion, indicating that individuals tend to develop a greater capacity to treat themselves with kindness as they grow older. This aligns with prior research demonstrating gradual increases in self-compassion across adulthood (

Bratt & Fagerström, 2020;

Homan, 2016;

Karakasidou et al., 2020;

Lee et al., 2021;

Murn & Steele, 2019;

Stapleton et al., 2018). Theoretical perspectives suggest that this increase may be linked to

Erikson’s (

1968) stage of Ego Integrity, which fosters holistic self-acceptance and emotional balance (

Neff, 2011). Additionally, cognitive and emotional maturation over the lifespan promotes wisdom and self-awareness, supporting a balanced perspective on personal flaws and life challenges (

Neff, 2023;

Karakasidou et al., 2020). Consistent with these findings, age was negatively correlated with symptoms of anxiety and depression. Older adults’ life experience, emotional maturity, and enhanced self-compassion likely contribute to this reduction in psychological distress (

Karakasidou et al., 2020;

Neff, 2011,

2023). Moreover, higher levels of self-compassion were associated with lower anxiety and depression symptoms across all adult age groups, corroborating previous research across diverse populations (

Callow et al., 2021;

de Souza et al., 2020;

H. Zhang et al., 2019). These findings suggest that self-compassion is a key emotion regulation strategy, mitigating self-criticism and promoting adaptive responses to distress. Taken together, these associations support Hypotheses 1 and 3, indicating that higher self-compassion and older age are associated with lower levels of anxiety and depressive symptoms.

The present study also found a statistically significant negative correlation between age and symptoms of anxiety and depression. This finding may be explained by age-related advantages such as life experience, emotional maturity, wisdom, holistic self-acceptance, and a sense of completeness and fulfilment, all of which promote compassionate self-treatment in the face of life’s challenges (

Karakasidou et al., 2020;

Neff, 2011,

2023). Specifically, these advantages encourage individuals to adopt a stance of warmth and self-acceptance during distress, to perceive adversity as a regular part of the human experience, and to regulate painful thoughts and emotions in a balanced manner. This, in turn, contributes to higher levels of self-compassion, as proposed by

Neff (

2003a,

2003b). Consequently, lower levels of anxiety and depressive symptomatology observed in older age groups may reflect this combination of life-acquired resources and elevated self-compassion. These results are consistent with Hypothesis 3, which proposed that older age would be associated with lower levels of psychological distress.

Regarding the relationship between SSCS and anxiety and depression symptoms in adults, the results revealed a statistically significant negative correlation. Higher levels of self-compassion were associated with lower levels of anxiety and depressive symptoms. These results align with prior research. For example,

de Souza et al. (

2020), in a study of the general Brazilian population, found that higher self-compassion was linked to lower levels of anxiety, stress, and depression symptoms. Similarly,

Callow et al. (

2021) reported that greater self-compassion weakened the relationship between externally induced shame and anxiety and depressive symptomatology. Thus, adopting a compassionate attitude toward oneself during painful or difficult moments serves as an important emotion regulation strategy that mitigates the negative effects of perceived criticism and adverse social evaluation on anxiety and depression symptoms. Furthermore,

H. Zhang et al. (

2019) found that self-compassion was negatively associated with both harsh self-criticism and depressive symptomatology. These findings suggest that cultivating self-compassion can serve as a protective resource against the detrimental effects of relentless self-criticism on depression symptoms, particularly among high-risk individuals with a recent history of suicide attempts. These results fully supported Hypothesis 1, which proposed that higher self-compassion would be associated with lower anxiety and depression.

Two-way ANOVA results revealed a significant effect of self-compassion on adults’ anxiety and depression symptom scores, highlighting its inverse association with psychological distress and underscoring its importance for emotional well-being (

Stapleton et al., 2018). This large effect indicates that differences in self-compassion account for a substantial proportion of the variability in these symptoms, suggesting that self-compassion functions as a central emotion regulation mechanism rather than a peripheral or age-dependent factor. Although participants were divided into three age groups (18–35, 36–50, 51–65), no significant interaction emerged between age and self-compassion in predicting either anxiety or depression symptoms, indicating that the association between higher self-compassion and lower distress was consistent across adulthood. No significant main effect of age was found for anxiety or depression symptoms despite the small negative correlations observed in preliminary analyses. This may suggest that age alone does not directly influence anxious or depressive symptomatology, and that other factors—such as physical health, coping strategies, or social support—may play a more substantive role in shaping these outcomes. The absence of interaction effects further supports the interpretation that self-compassion exerts similar psychological benefits across different adult stages, reducing both past-oriented rumination and self-criticism linked to depression, as well as future-oriented worry characteristic of anxiety (

Eysenck & Fajkowska, 2018). Overall, these findings confirm that cultivating self-compassion may serve as an effective emotion regulation strategy for mitigating psychological distress throughout adulthood (

Karakasidou et al., 2020;

Neff, 2011,

2023). These results did not support Hypothesis 2, which predicted age-related differences in the association between self-compassion and mental health symptoms. A key implication is that interventions aimed at enhancing self-compassion may be beneficial across the adult lifespan rather than being tailored to specific age groups. Future longitudinal or experimental studies could further examine whether the influence of self-compassion on mental health strengthens with age or remains relatively stable over time.

The results further indicated that self-compassion significantly and negatively predicted levels of anxiety and depression symptoms in adults, whereas age predicted lower anxiety but not depression. These findings may be interpreted in light of the virtues often associated with older age, such as life experience, emotional maturity, and heightened self-compassion. The broader literature provides strong evidence that self-compassion is a beneficial factor in reducing psychological distress across diverse populations. Specifically, the study by

Alsamman et al. (

2024), focusing on a sample of displaced Syrians, identified self-compassion as a significant predictor of lower levels of anxiety, depression symptoms, and emotional distress. Similarly,

Karakasidou et al. (

2023), using a student population sample, reported that higher levels of self-compassion predicted lower levels of anxiety, stress, and depression symptoms, as well as higher levels of life satisfaction and subjective well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The moderation analysis clarified that age does not significantly alter the relationship between state self-compassion and depression symptoms. Although older adults tended to report slightly higher levels of self-compassion, the strength of the association between self-compassion and lower psychological distress remained consistent across age groups. This finding suggests that self-compassion functions as a general protective factor rather than an age-dependent mechanism. In other words, regardless of age, individuals with greater self-compassion experience fewer symptoms of depression. These results align with previous studies highlighting the universal benefits of self-compassion for emotional regulation and mental health (

Neff, 2003a;

Trindade & Sirois, 2021) and extend this evidence to a large Greek adult sample. Future research may explore whether life-stage factors, such as social roles or health challenges, influence the development of self-compassion over time, even if its protective effect remains stable.

Consistent with the depression model, the moderation analysis for anxiety showed that age did not significantly moderate the relationship between self-compassion and anxiety symptoms. Although older adults reported slightly lower overall anxiety levels, the strength of the association between higher self-compassion and reduced anxiety remained stable across age groups. This indicates that self-compassion is broadly beneficial for emotional well-being regardless of age. This finding aligns with previous research showing that self-compassion enhances adaptive coping and emotion regulation across the lifespan (

Germer & Neff, 2013;

Trindade & Sirois, 2021).

Supporting evidence from clinical and general population studies reinforces this conclusion.

Zhu et al. (

2019) found that shortly after a cancer diagnosis, higher levels of the positive components of self-compassion significantly predicted reduced severity of anxiety, depression symptoms, and exhaustion throughout treatment. These benefits were more substantial when individuals engaged with the positive aspects of self-compassion rather than merely minimizing negative components such as self-criticism and isolation. Similarly,

Stapleton et al. (

2018) demonstrated that the negative aspects of self-compassion—often described as “self-coldness”—are strong predictors of psychological distress, whereas positive components are linked to resilience and emotional balance.

Trindade and Sirois (

2021), studying adults with idiopathic inflammatory bowel disease, further identified self-compassion as a protective factor associated with reduced anxiety, stress, and depression symptoms, with specific dimensions such as mindfulness exerting particularly strong beneficial associations. Conversely, the isolation dimension predicted higher depressive symptoms.

These mechanisms are theoretically supported by Neff’s model of self-compassion, which posits that mindfulness helps individuals approach painful thoughts and emotions with balanced awareness, reducing both avoidance and over-engagement (

Neff, 2003a,

2003b). The common humanity component also plays a central role by framing suffering as a shared human experience rather than as an isolating event (

Neff, 2003a,

2003b).

López et al. (

2018) similarly found that negative dimensions of self-compassion, especially isolation, predicted higher depressive symptoms even one year later in a general population sample. Additionally,

Baker et al. (

2019) demonstrated in a sample of adults with epilepsy that higher self-compassion predicted lower anxiety and depression symptoms and greater resilience.

Taken together, these findings underscore the role of self-compassion as an internal psychological resource that promotes adaptability and resilience in the face of adversity (

Bluth et al., 2018;

Nery-Hurwit et al., 2018). Consistent with the present study’s result, showing that higher self-compassion predicted lower anxiety and depression symptoms, state self-compassion appears to contribute meaningfully to emotional well-being across diverse contexts and throughout adulthood.

4.1. Practical Implications

The findings have important implications for counselling psychology, public mental health interventions, and prevention programs. First, they support the use of self-compassion-based interventions (e.g., Mindful Self-Compassion training, Compassion-Focused Therapy) across a range of adult populations as practical tools for alleviating distress and enhancing well-being (

E. Beaumont et al., 2025;

Ferrari et al., 2019;

Gilbert & Irons, 2004). Second, although no significant interaction between age and self-compassion was observed, age-related considerations remain important for tailoring interventions to developmental needs. Young adults, in particular, may benefit from early training in self-compassion to navigate the stressors associated with academic transitions, career uncertainty, or relationship difficulties (

Karakasidou & Stalikas, 2017a). For older adults, self-compassion practices may enhance reflection, self-acceptance, and emotional resilience—key themes in late-life psychological development (

Bratt & Fagerström, 2020;

Erikson, 1968).

Moreover, the growing availability of digital self-compassion interventions presents scalable solutions for mental health promotion, especially in contexts of limited access to psychological care. Mobile apps and online programs (e.g., The Self-Compassion App;

Northover et al., 2021) have demonstrated efficacy in enhancing emotional regulation and reducing psychological distress across settings and age groups. From a public health perspective, promoting self-compassion can be a cost-effective preventive strategy, especially when embedded in schools, universities, community centres, or workplaces. Given its demonstrated link with resilience, emotional stability, and interpersonal functioning (

Toplu-Demirtaş et al., 2018;

J. W. Zhang et al., 2019), self-compassion may be a foundational skill in comprehensive mental health education. Overall, the findings highlight self-compassion as a key emotional regulation mechanism that has a protective association against anxiety and depression symptoms across adulthood.

4.2. Limitations

Despite its strengths, the study is not without limitations. First, its cross-sectional design does not permit causal inferences. Although regression and ANOVA analyses suggest associative relationships, longitudinal designs are necessary to establish directionality and assess temporal changes in self-compassion and mental health (

Wang & Cheng, 2020). Second, using self-report instruments, while practical and psychometrically validated, may be subject to response biases such as social desirability or recall inaccuracies (

Demetriou et al., 2015). While online administration is convenient (

Ball, 2019), future studies could also collect in-person data to ensure participation and equitable representation of individuals lacking digital resources or skills, particularly among older adults. Future studies should incorporate multi-method approaches, including clinician-rated or ecological momentary assessments (EMA) (

Oranga, 2025). Third, the non-probabilistic sampling (via the snowball technique) limits the generalizability of findings. Although the sample was diverse in terms of age and education, it may not represent broader demographic groups (

Findley et al., 2021). Stratified or representative sampling across diverse socioeconomic and clinical backgrounds would enhance the external validity of future studies (

Caruana et al., 2015). In addition, online snowball sampling may have introduced selection bias by over-representing individuals with digital access and interest in psychological topics.

4.3. Future Directions

Future research should employ longitudinal designs to examine the developmental trajectories of self-compassion and its evolving influence on psychological health. Investigating moderators and mediators, such as gender, coping style, and attachment, may clarify factors that affect the strength of self-compassion’s protective role. Additionally, it is important to evaluate the effectiveness of interventions across different age groups, with particular attention to digital formats that incorporate feedback, personalisation, and engagement strategies. Including clinical samples, such as individuals with anxiety disorders, depression symptoms, or chronic illnesses, would further allow researchers to assess differential effects and optimise treatment adaptations. Overall, the present findings provide compelling evidence that self-compassion is a vital psychological resource that supports emotional well-being across adulthood. SSCS consistently predicted lower symptoms of anxiety and depression across all age groups, without evidence of age-related moderation. Future longitudinal studies may further explore whether developmental factors shape the expression of self-compassion over time, even though no moderation was observed in the present data. These results highlight the importance of integrating self-compassion training into mental health programs and counselling practices and underscore the need for continued investigation into how self-compassion evolves and functions throughout the lifespan.

5. Conclusions

The present study examined the associations among state self-compassion, age, and symptoms of anxiety and depression in a large Greek adult sample. Across all analyses, higher state self-compassion was consistently associated with lower levels of psychological distress, supporting its role as an important emotional regulation resource in adulthood. Although age showed small negative correlations with anxiety and depression symptoms and a small positive correlation with state self-compassion, the two-way ANOVA indicated that age groups did not differ significantly in depression scores and showed only minimal differences in anxiety scores. Notably, no interaction effects emerged between age groups and self-compassion levels.

Crucially, the moderation analyses using the PROCESS macro showed that age did not moderate the association between state self-compassion and symptoms of anxiety or depression. This indicates that the strength of the association between self-compassion and psychological distress remains stable across adulthood, rather than varying by age. In other words, the psychological benefits linked with higher state self-compassion appear to be comparable for younger, middle-aged, and older adults.

Taken together, the findings underscore state self-compassion as a meaningful correlate of emotional well-being throughout adulthood and suggest that interventions fostering self-compassion may be valuable across age groups. Future longitudinal and experimental studies are needed to clarify potential developmental trajectories of self-compassion, examine causal mechanisms, and assess how self-compassion-based interventions function across different stages of adult life.