1. Introduction

The interplay between motherhood experience and leadership development presents a multifaceted panorama. Traditionally, gender roles have positioned women predominantly as caregivers, with men viewed as primary earners (

Voydanoff, 2002). Recent societal shifts toward dual-earner households have prompted more women to assume leadership roles alongside maternal responsibilities. Nevertheless, existing literature underscores structural challenges, with motherhood often perceived as disadvantageous in professional settings. Studies consistently highlight maternal biases, adversely affecting perceptions of professional competence and career advancement opportunities for mothers (

Arena et al., 2023;

Heilman & Okimoto, 2008).

Viitanen (

2014) further emphasizes enduring economic penalties mothers face, directly impeding their career trajectories. Similarly,

Ridgeway and Correll (

2004) demonstrate that motherhood negatively biases evaluations of women’s leadership potential, intensifying discrimination and hindering career progression.

However, recent research has begun to recognize motherhood as a potential source of positive leadership transformation. For instance, reflective leadership processes among mothers have been shown to enhance self-awareness, empathy, authenticity, and relational capacities, characteristics central to inclusive leadership paradigms (

Akerjordet & Severinsson, 2010).

Lumby and Azaola (

2014) similarly demonstrate how motherhood deeply influences female leaders’ approaches, significantly reshaping interactions with subordinates.

Leadership development literature predominantly explores lifespan-based (

Liu et al., 2021), identity-based (

Komives et al., 2005;

Lord & Hall, 2005), skill-based (

Lacerenza et al., 2017;

Mumford et al., 2000), and experience-based perspectives (

Zacharatos et al., 2000). Yet, the specific mechanisms through which motherhood experiences foster leadership resilience and enhance leader–follower relational dynamics remain underexplored. This gap is particularly notable given the relational essence of effective leadership emphasized in contemporary organizational contexts.

Addressing this gap, this study explores how adversities encountered through motherhood facilitate a form of “transformative resilience”—a newly articulated concept proposed herein. We define transformative resilience as the capacity to proactively leverage adversities, transforming these experiences into enhanced relational and inclusive leadership qualities. Drawing upon relational leadership theory (

Uhl-Bien, 2006), we posit that motherhood-related adversities can serve as powerful catalysts for leaders to reshape their interactions with followers, thereby fostering more empathetic, authentic, and inclusive relational dynamics.

As reviewed by

Sato (

2019), the grounded theory approach (GTA) pioneered by

Glaser and Strauss (

1967) is frequently cited for its methodological validity in qualitative theory-building studies, in contrast with quantitative studies that tested hypotheses derived from established theories. In this exploratory study with the purpose of formulating a tentative theoretical framework of transformative resilience among maternal leaders, we thus adopted the GTA and its analytic technique, drawing insights from

Patterson and Kelleher’s (

2005) resilience framework. Consequently, our research identifies a three-stage transformative resilience process experienced by maternal leaders. These stages involve encountering motherhood adversities, engaging in identity reinterpretation and capability cultivation, and ultimately adopting inclusive relational leadership practices that profoundly transform leader–follower interactions.

This study contributes to leadership scholarship by introducing the concept of transformative resilience as a critical theoretical advancement, explicitly linking personal resilience developed through motherhood with relational leadership practices. Furthermore, it provides practical implications by offering guidance to organizations seeking to support maternal leaders, thereby enhancing relational quality and inclusivity within organizational contexts.

1.1. Literature Review

Motherhood Experience and Leadership Development

The intersection between motherhood and leadership development is shaped by enduring social expectations and structural asymmetries within organizational contexts. Historically, leadership has been characterized by traits such as autonomy, decisiveness, and instrumental rationality—qualities that have been culturally associated with masculine norms and misaligned with caregiving roles (

Eagly & Carli, 2007;

Ridgeway & Correll, 2004). In contrast, motherhood has often been relegated to the private sphere, framed as emotionally intensive, morally laden, and incompatible with professional leadership roles. These cultural assumptions have produced systemic disadvantages for mothers in leadership pipelines, manifesting as both attitudinal bias and institutional constraints.

Extensive empirical evidence documents the “motherhood penalty”—a pattern in which mothers are perceived as less committed, less competent, and less promotable than non-mothers (

Heilman & Okimoto, 2008;

Arena et al., 2023). These perceptions often translate into tangible career consequences, including reduced access to leadership opportunities and long-term wage suppression (

Viitanen, 2014).

Ridgeway and Correll (

2004) further argue that motherhood status constitutes a uniquely salient basis for discrimination, surpassing gender alone in shaping organizational evaluations. In sum, dominant leadership discourses have largely marginalized motherhood as a legitimate source of professional capacity.

Nonetheless, emerging studies have begun to reconsider this framing, noting that caregiving experiences may cultivate interpersonal and emotional competencies relevant to leadership roles. For instance, mothering often entails managing moral tensions, emotional unpredictability, and relational complexity—conditions that some scholars argue mirror the demands of contemporary, post-heroic leadership models (

J. K. Fletcher, 2004;

Uhl-Bien, 2006;

Alvesson & Einola, 2019). Research in nursing and education suggests that maternal experience can foster empathy, emotional regulation, and reflective practice—capacities associated with inclusive and relational leadership (

Akerjordet & Severinsson, 2010;

Lumby & Azaola, 2014).

However, despite these insights, the theoretical and empirical literature remains fragmented. Most contributions either document bias against mothers or invoke positive qualities associated with caregiving, but few studies have systematically analyzed how maternal experiences shape leadership development. Moreover, the mechanisms through which caregiving adversity might inform leader identity, behavior, or interpersonal judgment remain largely unarticulated. Leadership development frameworks, while extensive, have typically emphasized formal training, mentorship, or professional transitions (

Komives et al., 2005;

Lord & Hall, 2005;

Mumford et al., 2000), seldom incorporating private domain experiences as sites of leadership learning.

This under-theorization points to a critical gap in understanding how personal adversity, particularly within family and caregiving contexts, contributes to leadership formation. While scattered evidence suggests that maternal roles may enhance certain relational competencies, the field lacks an integrated account of how such experiences interact with leadership development processes. This absence raises important questions about the validity of dominant leadership paradigms and their exclusion of alternative, embodied forms of learning.

1.2. Resilience Theory: Development and Current Limitations

Individual resilience has been widely studied in the stress and coping research and broadly conceptualized as a stable personality trait (

Block & Kremen, 1996), a state-like developable capacity (

Connor & Davidson, 2003), or a process (

Patterson & Kelleher, 2005). The early trait-oriented view emphasized the role of individual differences in predicting resilience outcomes, with research often focusing on psychological attributes such as optimism, adaptability, and emotional stability as central resilience factors (

Connor & Davidson, 2003). The capacity perspective is more often found in the workplace resilience research. When resilience is construed as a state-like attribute, which is malleable and developable, managers can focus on effective interventions to build employee resilience for positive adaptation in the face of adversity and prepare employees for better coping with future adversity (

Luthans, 2002). In a recent study on Taiwanese workers, researchers have found that building a wellness-based positive work environment effectively fostered employee resilience which then led to enhanced future job performance (

Chen et al., 2025). This is a rare demonstration of cross-level transformation of resources, from organizational resources to personal resources, in the organizational context. Extending the above study on transformative resilience and capacity-building potential in the workplace, we further draw insights from the more dynamic, process-oriented view on resilience. The process-oriented view conceptualizes resilience as an ongoing adaptive process, recognizing its complex interaction with environmental contexts and personal experiences (

Rutter, 2012;

Windle, 2011;

Waugh & Koster, 2015).

Patterson and Kelleher (

2005) notably contributed to this dynamic perspective by proposing a comprehensive, multi-stage model of resilience development. Their model articulates resilience as a non-linear, iterative process involving six interconnected stages: encountering adversity, interpreting adversity, cultivating resilience capabilities, engaging in resilient actions, achieving successful adaptation, and enhancing resilience for future challenges. This model emphasizes the continuous interaction between understanding (sense-making), capability cultivation (developing psychological and interpersonal resources), and proactive actions (coping behaviors and adaptive responses). Patterson and Kelleher’s framework highlights that resilience is actively constructed and continuously evolving, rather than passively possessed or inherently fixed.

Despite these significant theoretical advancements and bourgeoning research during the pandemic, we know very little about how resilience processes unfold uniquely within identity-rich personal experiences such as motherhood and how these learnings spill over and transfer into the work realm to foster leadership development. A critical gap remains regarding the detailed mechanisms by which motherhood experiences—characterized by significant personal adversity and transformative potential—can foster resilience processes that directly enhance leadership capacities and relational competencies within organizational settings. By exploring this gap, this study seeks to elucidate how resilience developed through motherhood experiences translates specifically into enhanced relational skills and leadership effectiveness, thereby contributing to a more nuanced understanding of resilience as a contextually embedded, dynamic, and transformative process.

Our efforts corroborate the theoretical development of relational leadership, which recognizes the profound impact personal experiences exert on leadership styles and effectiveness (

Uhl-Bien, 2006). Specifically, we explored the intersection of motherhood, resilience, and leadership development by asking: How does resilience developed through motherhood experiences translate concretely into female leaders’ interactions with their followers, and how might this transformation influence their inclusive leadership practices? Examining this question through a systematic inquiry aligned with the grounded theory approach, a transformative resilience framework emerged from the empirical data. Our study thus contributes to both scholarly theorization and organizational practice in supporting more inclusive and resilient forms of leadership.

3. Results

Banister et al. (

1994) advised that it may be more appropriate to combine the results and discussion sections together, due to the iterative and mutually immersive nature of data and their meanings in qualitative research. It is thus the convention to present the theoretical categories rooted in the interview verbatim and conceptualize the interrelations between these categories in one section, and then go on to discuss wider issues and theoretical implications in a separate section. We thus follow this practice in presentation using the GTA in the management research (

Sato, 2019).

Through a rigorous thematic analysis of maternal leaders’ lived experiences, we discovered a distinct and iterative process of resilience-building, which we term “Transformative Resilience.” Importantly, we do not suggest that the mother-child relationship directly mirrors or equates to leader–follower relationships. Rather, we argue that the psychological capabilities—such as empathy, emotional regulation, and adaptability—cultivated through the personal adversity encountered in motherhood can be proactively transferred and applied to leadership practices within professional contexts.

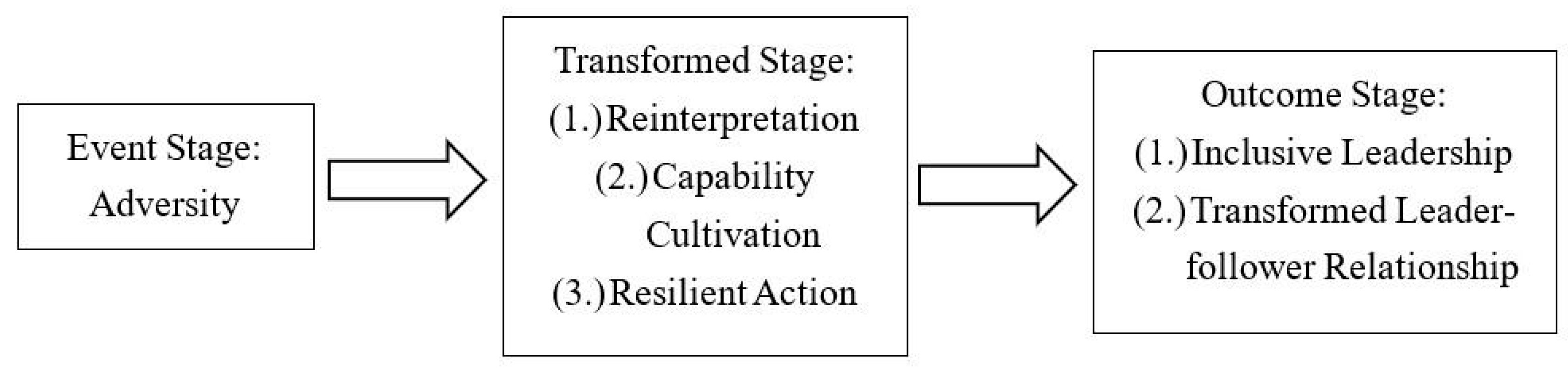

Our analysis delineates the transformative resilience process as unfolding clearly through three interconnected stages (see

Figure 1). (1) Event Stage: This initial phase captures how maternal leaders encounter and interpret motherhood-related adversities. Here, leaders identify critical challenges in their motherhood experiences, creating the necessary impetus for subsequent psychological transformation. (2) Transformed Stage: Central to our model, this stage comprises three key subprocesses: (A) Reinterpretation: Leaders actively reevaluate adversities to form new, constructive meanings from their motherhood experiences. (B) Capability Cultivation: Following reinterpretation, leaders consciously cultivate specific psychological capabilities relevant not just in the family domain but also highly applicable in leadership contexts (e.g., empathy, patience, inclusive communication skills). (C) Resilient Action: Leaders deliberately apply these cultivated psychological capabilities in concrete leadership behaviors and interactions within their professional roles. (3) Outcome Stage: The transformative resilience process culminates in two significant outcomes: (A) Inclusive Leadership styles: Leaders develop leadership styles that are notably more inclusive, characterized by openness, empathy, appreciation of diversity, and heightened relational quality. (B) Transformed Leader–Follower Relationships: The developed resilience capabilities facilitate enhanced relational dynamics, fostering mutual trust, psychological safety, and effective collaboration in leader–follower interactions. In the sections that follow, we present detailed empirical evidence supporting each stage of the transformative resilience process. All quotations from participants are presented in verbatim, rigorously preserving their original words to ensure transparency and authenticity in our analytical interpretations (refer to

Table 1 for comprehensive participant quotations and thematic codes).

Through clearly presenting this empirically grounded resilience-building process, our study not only extends existing resilience theory by articulating the specific mechanisms of active cross-context transformation, but also contributes significantly to relational and inclusive leadership theories. In doing so, we provide a nuanced understanding of how motherhood experiences serve as a fertile ground for developing psychological capabilities that have substantial relevance to leadership effectiveness.

3.1. Event Stage: Adversities Arising from the Mother-Child Relationship

In the Event Stage, our analysis places particular emphasis on the adversities maternal leaders encounter, especially those rooted in challenges within mother-child relationships. Participants described complex emotional struggles far beyond the commonly discussed work-family conflicts, including difficulties in understanding their children’s needs from infancy onward, disappointment regarding academic performance, feelings of parental helplessness, and navigating their children’s unconventional developmental paths. Collectively, these challenges generate substantial emotional and psychological tension for female leaders.

Interviewee 23 shared how unmet expectations prompted profound introspection: “However, when you become a dedicated parent, especially when your child does not meet expectations, your heart softens. You start to see the flaws in the entire elitist system, leading to its dismantling and rebuilding.” Similarly, Interviewee 28 recounted an emotionally intense experience during her daughter’s adolescence: “After (my daughter) entered adolescence, and with many things happening later on, she got depression. It was only then that I realized how crucial listening is.” These narratives illustrate how unforeseen adversities related to children can fundamentally challenge leaders’ initial perceptions and expectations.

Corroborating narratives further demonstrate how maternal adversities elicit not only emotional turbulence but also transformative re-evaluation. Interviewee 2 recalled a deeply distressing moment when her child, undergoing early intervention for developmental delay, was crying while she was forced to continue a professional call in the car:

“I vividly remember my son had developmental issues … I was taking him to class and had just parked when the phone rang. I had to talk to clients while he cried in the background … After the call, they kept apologizing, but I felt terrible.”

She later reflected on the dissonance between her professional identity and her maternal instinct:

“Why am I wasting time on things like this? I should be spending more time with my son.”

Such moments reveal the emotional fragmentation faced by maternal leaders and how these tensions can ultimately drive changes in value hierarchies and relational priorities.

Likewise, Interviewee 10 described the emotional suffocation she experienced after over a decade of running a company while raising three children:

“My husband and I gave everything to our work for 13 years, but we had three children … and I was almost suffocating.”

This realization led her to radically alter her professional role and reorient her priorities:

“I made a resolution that in the year 2000, I would live a different kind of life.”

Her story illustrates how long-standing emotional strain can lead to deep life redesign—not merely to achieve balance, but to reclaim meaning and connection in both work and family domains.

Interviewee 26 also emphasized shifts in mother-child interactions and communication, driven by generational differences: “She taught us that it’s important to speak kindly. She doesn’t take well to yelling or shouting.” This insight highlights the importance of personal adaptability and emotional openness required in contemporary parenting, reflecting broader changes in familial dynamics.

Together, these experiences vividly illustrate how maternal adversities—particularly those associated with emotional tensions in mother-child interactions—initiate a critical emotional and cognitive re-evaluation process. Rather than perceiving these events as purely negative, maternal leaders recognize them as catalysts for developing key psychological capacities such as empathy, emotional sensitivity, adaptability, and nuanced interpersonal skills. These emotional and cognitive shifts serve as foundational psychological resources for transformative resilience, subsequently informing their inclusive and relational leadership behaviors within professional contexts.

3.2. Transformed Stage:The Transformative Resilience Process

3.2.1. Reinterpretation: Reevaluating Adversity and Gaining New Perspectives

Different adversities lead maternal leaders to engage in deep reflection, prompting them to reassess their personal values and worldviews. A common experience mentioned by participants involves their children not meeting expected milestones, which serves as a significant prompt for introspection. For example, Interviewee 23 shared: “Having children led me to some introspection and reflection. Life can take many forms, and people have different traits and needs. This realization has been helpful in my leadership and organizational roles. For instance, I now tend not to judge my colleagues for lacking skills or not putting in enough effort. I avoid labeling them simply. I believe it’s more about not having found the right approach or consensus … I now think deeper about the reasons behind a person’s behavior.”

The diversity of personal values significantly influences how these adversities are interpreted. Some leaders initially view motherhood as detrimental to career development, while others reframe these experiences positively as learning opportunities. Interviewee 11, for example, described motherhood positively: “I wouldn’t call it adversity. In fact, I learned a lot from them in terms of communication skills and interpersonal relationships. They’ve given me valuable insights that I can apply to my work.”

Interviewee 16 described how internalized pressure and guilt gave way to deeper understanding and emotional balance: “I kept feeling like I wasn’t doing enough, but in reality, my child’s needs were already being met. Their expectations were much lower than I assumed. I was overthinking it. Eventually, I learned to deconstruct this guilt, and that allowed me to find a better balance.”

Interviewee 26 emphasized how child feedback significantly reshaped her perspective: “Because of the feedback our child gives us … it makes us look at many things in the world from a different perspective.”

These narratives collectively illustrate how maternal adversities provoke profound cognitive reinterpretations. Rather than perceiving these adversities purely negatively, maternal leaders actively reframe these experiences, deriving insights such as empathy, openness, and sensitivity to diverse perspectives. These capabilities, cultivated initially through personal experiences in motherhood, subsequently become foundational psychological resources, fostering inclusive and relational leadership development.

3.2.2. Capability Cultivation: Developing and Enhancing Resilience Abilities Through Motherhood Challenges

Experiencing adversities in motherhood, particularly when children’s performance or behaviors do not align with maternal expectations, often prompts leaders to reassess their values and expand their coping abilities. Our findings indicate that maternal leaders actively cultivate specific psychological capabilities—such as empathy, patience, adaptability, inclusiveness, and refined communication skills—in response to these personal challenges. These cultivated capabilities subsequently provide essential resources that maternal leaders proactively leverage in their leadership roles, significantly enhancing the quality of their interactions with followers and influencing their inclusive and relational leadership practices. This active transfer of emotional and relational capabilities aligns with recent insights from attachment theory, which emphasizes how secure relational foundations can positively influence organizational interactions and leadership effectiveness (

Yip et al., 2022).

Interviewee 24 highlighted how motherhood significantly enhances empathy and inclusiveness toward individual differences: “I believe that being a mother allows us to have more empathy towards the individual differences in talents and insights. The fact is, every child is unique, and so is every person with their own strengths and weaknesses. Therefore, understanding and leveraging each person’s strengths becomes a broader view in how you interact and develop them.” She further elaborated that maternal experiences foster greater inclusivity toward distinct personal traits: “If you have this perspective, you’ll understand that naturally some people are more detail-oriented, while others are more impulsive, have a bigger picture mindset, or are better at interacting with others. These individual traits are distinct in each person, and you can see this even in children from birth. I believe that being a mother inherently fosters more empathy, and mothers tend to show more concern and love towards their subordinates.”

Moreover, the majority of interviewees emphasized significant improvements in communication abilities directly resulting from their motherhood experiences. For example, Interviewee 20 stated succinctly: “Improved emotional management as a mother is helpful for communication with subordinates.” Interviewee 17 further highlighted how motherhood experiences explicitly cultivated her interpersonal skills: “After having children, I learned to communicate, compromise, express ‘please, thank you, sorry’ more easily, have patience to listen to others, and have empathy.”

Patience also emerged consistently as a critical psychological capability developed through maternal experiences. Interviewee 27 described how motherhood positively affected her professional interactions: “In discussions or meetings, you actually have a bit more patience to listen to what they are saying. Although I already make an effort to listen, I find myself even more patient in these situations, trying to understand their perspectives better and guide towards possible issues or potential solutions. This is something I believe I can approach from this perspective.”

Participant 22 described how managing emotional reactions in parenting directly informs her leadership interactions: “Sometimes I lose my temper with my child, but I still have to calm down and adjust my tone. You can’t just yell at them. As a mother, you pause and think: if this were a team member, how would I respond?”

Additionally, dealing with unmet expectations at home can teach maternal leaders the value of flexibility and adaptability. They often apply these insights in their professional roles, cultivating more accommodating work environments sensitive to diverse team members’ needs and circumstances. Interviewee 23 reflected thoughtfully on this point: “Actually, becoming a parent makes it clear that your child is not just your child; they are their own person. Similarly, colleagues are also individuals in their own right. In the company, I often tell my colleagues that many supervisors feel that someone resigning is like a betrayal, or they think that today’s youth lack goals and direction. There are various comments about young people, but I don’t see it that way. I don’t believe my goals have to be your goals … Then, we should cooperate, helping each other progress towards our individual goals. It’s great to have the chance to walk this journey together. In this phase, we grow together.”

Interviewee 24 similarly emphasized that maternal leaders generally demonstrate higher flexibility due to their intimate experiences with navigating personal expectations versus reality: “In terms of proportions, usually, those who are mothers tend to have greater flexibility. This is because, in the process of motherhood, they internally deal with a lot regarding their children. They have to accept that their expectations of their children might not always match reality. So, they tend to be more aware of human limitations, having nurtured a life with its many conditions. This experience gives them a higher degree of tolerance and patience.”

Collectively, these narratives illustrate how motherhood adversities provide maternal leaders with critical opportunities for capability cultivation. Through actively responding to motherhood challenges, they develop essential resilience capacities—including empathy, patience, inclusive communication, and adaptability. These psychological capabilities, initially nurtured in personal motherhood contexts, become vital psychological resources that leaders proactively transfer and apply in their professional roles, significantly enriching their inclusive leadership approaches and enhancing leader–follower relational dynamics.

3.2.3. Resilient Action: Practicing Cultivated Capabilities Through Concrete Leadership Behaviors

After cultivating critical psychological capabilities such as empathy, patience, and inclusive communication from adversity encountered in motherhood, female leaders proactively transfer and implement these capabilities within professional leadership contexts.

Participants explicitly reported practicing these capabilities in concrete relational and inclusive leadership actions, specifically emphasizing enhanced communication with followers, increased openness to followers’ feedback, and more human-oriented leadership interactions. Interviewee 28 explicitly illustrated how she proactively applies her enhanced communication capability in concrete organizational practices, establishing dedicated mechanisms to collect employee feedback, thereby fostering an inclusive and responsive organizational climate: “I formed a team that consistently tracks the company’s status. The team is called ‘employee engagement’ in our company, and they continuously track the feedback employees provide to the organization. Through this, I demonstrate to everyone, starting with my leadership team, what our employees want and don’t want.”

This explicit action clearly illustrates how a maternal leader deliberately transfers capabilities cultivated from personal experiences—specifically active listening and empathy—into professional leadership contexts, significantly enhancing the relational quality and inclusivity of organizational interactions.

Similarly, Interviewee 24 shared how her motherhood experiences heightened her sensitivity to interpersonal communication gaps, enabling her to approach workplace communication challenges with greater empathy, understanding, and patience: “Because through the process of dealing with children, you become acutely aware that even with close family members who live together every day, miscommunication can happen…So when you encounter challenges or complaints from others in the workplace, you should understand their agenda setting, they care about what? Therefore, you can better approach the situation with a calm mind and first understand others.”

This narrative explicitly demonstrates how resilient capabilities developed in response to personal adversities are proactively transferred into professional relational interactions, directly improving leaders’ ability to manage and respond constructively to communication challenges at work.

Collectively, these explicit actions exemplify resilient action as the active, deliberate, and systematic transfer of resilience capabilities developed in the personal context of motherhood into professional leadership practices. Maternal leaders not only cultivate key psychological capabilities through motherhood adversity but proactively practice these capabilities in leadership behaviors that foster enhanced communication, inclusivity, openness, and interpersonal understanding within their teams. These empirical examples provide clear support for the transformative resilience process, illuminating how personal resilience experiences explicitly inform and transform professional leadership interactions and effectiveness.

3.3. Outcome Stage: Inclusive Leadership Developed and Transformed Leader/Follower Relationship

The culmination of the transformative resilience process results in significant leadership outcomes, specifically in two intertwined areas: inclusive leadership development and the transformation of leader–follower relationships. In terms of inclusive leadership development, maternal experiences often lead leaders to embrace more inclusive approaches, recognizing and valuing individual differences within their teams. Interviewee 23 offered profound insights into how parenting experiences shaped her inclusive leadership philosophy: “Children are a direct reflection that helps you see yourself … We are both independent and imperfect individuals.”

She further explained how the recognition of her child’s individuality transformed her leadership mindset toward a more inclusive and less hierarchical approach in her professional role: “As parents, we understand clearly that our children are not really ours, but their own selves. Similarly, our colleagues are also individuals in their own right. I personally don’t believe that my goals must align with those of my subordinates. I see it as climbing a mountain where we all have different peaks to reach. However, there may be a phase in life where we walk the same path, in the same direction. During this time, we should cooperate and support each other. Helping you also helps me advance towards my own peak. It’s a privilege to share this journey together. I believe it’s wonderful that we can grow mutually during this part of our lives.” These reflections challenge traditional hierarchical leadership views, highlighting the importance of embracing individuality and supporting mutual growth within professional environments.

The theme of transformed leader–follower relationships emerges clearly in these narratives. Interviewee 23 described her leadership transition from a traditional, top-down approach to a more empathetic, understanding, and collaborative style. She emphasized the importance of recognizing each individual’s unique aspirations and motivations: “It’s about finding what motivates each person … Everyone comes here with their own aspirations.”

This approach reflects a leadership perspective that values individual goals, enhancing workforce motivation and productivity through empathetic understanding. Interviewee 23 further commented on the benefits of such inclusive leadership within her organization: “Colleagues are more autonomous and passionate … they are pursuing their own North Star.” This quote exemplifies a leadership environment that aligns individual aspirations with organizational objectives, fostering shared purpose and collaboration.

Interviewee 28 provided further insights into how parenting experiences directly influenced leadership transformation, particularly emphasizing the enhanced sensitivity toward employees’ unique needs: “Parents often feel a strong impetus to adapt due to their child’s unique circumstances. This becomes particularly evident when the parent is a leader, often in a high-ranking executive position. I believe that most will transport this experience into their workplace. That is, the reflections and transformations they undergo at home get carried over to their professional life, leading to a change in their leadership style. Especially for a leader, when your team is not very large, every word you say counts.” She additionally underscored the significance of actively supporting employee career development and well-being: “You have to let employees know that they are not just contributing, but we are also very invested in their career development and well-being.”

Further emphasizing inclusive practices, Interviewee 28 described the critical role of a support system, such as HR, in maintaining a productive and healthy workplace: “In our journey, it’s easy to get off track sometimes, and you must have a mechanism in place, a kind of brain trust to help you get back on course. That’s where our company’s HR becomes crucial.”

Interviewee 27 provided tangible evidence of the effectiveness of this inclusive leadership transformation, highlighting significant organizational improvements, particularly in reduced employee turnover and increased productivity: “My turnover rate has dropped to 7%, from the original 30-something percent. It’s a significant change, and my employees’ productivity is also very high; we exceed our targets every year … Also, my employees are very capable and ready to act. This is because we have started providing training, so the new hires adapt and become proficient much faster.” This notable improvement illustrates how inclusive leadership practices, grounded in empathy, patience, and adaptability cultivated through motherhood experiences, significantly benefit organizational outcomes.

Finally, Interviewee 26 succinctly captured the profound personal transformation that motherhood catalyzes, directly enhancing leadership capacities: “Only after becoming a mother, to some extent, the child actually transforms us and changes us because they are an independent individual. We change for them because of love, a relationship, and a love that cannot be taken away, changed, or destroyed. I think love is the most important factor. Because of that love, we hope that our management or parenting of them is effective. With the premise of wanting it to be effective, the child brings about changes in us, which is essentially an enhancement of leadership.”

Collectively, these narratives provide clear empirical evidence of how maternal experiences foster inclusive leadership capabilities and transform leader–follower dynamics. They underscore how personal growth and resilience developed through motherhood adversities do not merely remain confined to personal contexts, but profoundly and proactively transfer into leadership development, significantly enhancing relational effectiveness, empathy, and inclusivity within professional environments.

4. Discussion

4.1. Theoretical Implications

This study contributes to resilience and leadership development studies by articulating and empirically validating a new novel theoretical construct: transformative resilience. Defined as a psychological process wherein individuals actively reinterpret personal adversities, intentionally cultivate new psychological capabilities, and deliberately transfer these capabilities across different contexts, transformative resilience extends beyond traditional resilience theories, such as those by

Masten and Obradović (

2006),

Connor and Davidson (

2003), and particularly

Patterson and Kelleher (

2005), which primarily conceptualize resilience as adaptive coping and recovery mechanisms. Our transformative model of maternal resilience mirrors the latest work on the transformation of organizational resources into employee resilience (

Chen et al., 2025), demonstrating that transformation can happen across levels (organization to personal), as well as across domains (familial to work and leadership development). The thrust of our model lies in the unraveling of the mechanisms enabling the active, cross-contextual transfer of resilience capabilities developed through motherhood experiences into professional leadership contexts.

Specifically, our findings extend

Patterson and Kelleher’s (

2005) resilience framework by clearly elucidating three interconnected dimensions that underpin transformative resilience: reinterpretation, capability cultivation, and resilient action. First, the dimension of reinterpretation involves proactive reframing of adversity, enabling leaders to reconstruct negative experiences as positive opportunities for growth (

Waugh & Koster, 2015;

D. Fletcher & Sarkar, 2013). While

Patterson and Kelleher’s (

2005) model emphasizes adversity interpretation, it lacks explicit explanation of how individuals systematically and actively reframe adversities across different roles or domains. In contrast, our study provides clear empirical evidence of maternal leaders actively engaging in reinterpretation processes initially developed through motherhood, subsequently transferring these reframing strategies into their professional leadership roles, significantly influencing their cognitive frameworks for leadership.

Second, our dimension of capability cultivation explicitly addresses existing resilience literature limitations, which typically focus on recovery-oriented coping and overlook the proactive cultivation of transferable psychological capabilities (

Luthar et al., 2000;

Norris et al., 2008). Our empirical findings explicitly demonstrate how maternal leaders deliberately cultivate critical psychological capabilities—such as empathy, patience, emotional intelligence, and inclusive communication skills—in response to motherhood adversities. These cultivated capabilities become crucial psychological resources explicitly transferred into professional contexts, thereby enhancing relational and inclusive leadership effectiveness (

J. K. Fletcher, 2004).

Third, the dimension of resilient action clearly advances resilience theory by illuminating the proactive application of psychological capabilities developed in personal contexts (such as motherhood) into distinctly different professional roles. Existing resilience frameworks primarily highlight recovery actions within the original adversity context, rarely detailing how individuals intentionally transfer these capabilities across contexts (

Patterson & Kelleher, 2005;

Windle, 2011). Our findings address this limitation by providing explicit evidence of maternal leaders actively translating motherhood-derived capabilities—such as empathy, adaptability, and inclusive communication—into professional relational leadership practices, significantly reshaping their leader–follower interactions toward greater inclusivity and collaboration (

Carmeli et al., 2010;

Nembhard & Edmondson, 2006;

Van Knippenberg & van Ginkel, 2022).

Beyond resilience literature, this study provides significant theoretical contributions to leadership development, particularly relational leadership theories. Our transformative resilience model explicitly fills this theoretical gap by clearly demonstrating how maternal leaders proactively cultivate critical relational capabilities—empathy, openness, and adaptability—and systematically transfer these capabilities into leadership interactions. This clear developmental mechanism significantly extends relational leadership theory, explicitly bridging personal psychological resilience development with relational leadership effectiveness. Our findings highlight motherhood adversities—particularly related to mother-child interactions—as powerful contexts prompting maternal leaders’ cognitive and emotional transformations. This explicit acknowledgment significantly advances leadership theories by illustrating how deeply personal experiences actively shape leaders’ relational, inclusive, and adaptive leadership capabilities.

4.2. Managerial and Practical Implications

Practically, our study provides valuable insights for organizational leadership development practices. By explicitly recognizing transformative resilience capabilities developed through motherhood experiences, organizations can proactively design leadership development programs that intentionally support female leaders during and after motherhood transitions. Such support acknowledges motherhood as a pivotal leadership development context, explicitly guiding female leaders to leverage resilience capabilities proactively cultivated through personal adversities into professional leadership effectiveness. This approach clearly addresses anxieties female leaders face regarding motherhood’s professional impacts, significantly enriching organizational inclusivity, retention, and leader effectiveness (

Eagly & Carli, 2007;

Kossek & Lautsch, 2018).

4.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

While this study sheds new light on how maternal adversity can serve as a developmental crucible for inclusive and human-centered leadership, several limitations warrant acknowledgment. First, our participants were all women who had already secured formal leadership roles, which may introduce a form of survivor bias. Their narratives, while rich in depth and insight, represent those who had the resilience, resources, or institutional support to remain in leadership trajectories. As such, the developmental struggles and leadership potential of women who faced overwhelming structural constraints—or who opted out of formal leadership roles altogether—remain underexplored. Second, this study was conducted in a specific sociocultural setting: Taiwan, a society where Confucian values of familial responsibility and relational harmony remain salient. The embeddedness of our data within this context necessitates caution in extrapolating our conclusions to cultures where motherhood, gender, and leadership are framed through different normative lenses. Third, the retrospective, self-narrated nature of our data may be influenced by selective memory, identity negotiation, or the desire to present a coherent leadership journey. While this is a common trade-off in narrative-based qualitative studies, it underscores the importance of methodological pluralism in future research.

Building upon our theoretical model of transformative resilience, future research could deepen this inquiry by examining whether and how motherhood adversity fosters distinct forms of leadership-related capacities beyond inclusivity. For instance, caregiving challenges may cultivate nuanced forms of moral discernment, emotion regulation, or long-term strategic patience—capacities particularly salient in volatile or relationally intensive work contexts. Exploring such leadership dynamics could enhance our understanding of how psychological growth is not only inwardly experienced but also outwardly enacted in complex organizational life. Furthermore, we call for studies that investigate the institutional environments and organizational conditions that either amplify or suppress the leadership potential developed through personal adversity. Research might examine how workplace cultures, HR systems, or leadership development programs differentially affect whether these personal insights are acknowledged, nurtured, or rendered invisible. Comparative studies across sectors or national settings could help delineate the structural pathways through which resilience forged in private domains becomes a public asset in leadership practice. Such research would extend the applicability of our findings and contribute to a broader agenda on human-centered and contextually grounded leadership development.