Psychometric Validation of the Trait Emotional Intelligence Questionnaire-Child Short Form (TEIQue-CSF) in a Greek Population

Abstract

1. Introduction

TEIQue-CSF in Greek Population

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Procedure

2.2. Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Aim

2.4. Ethics Approval of Research

2.5. Statistical Analysis

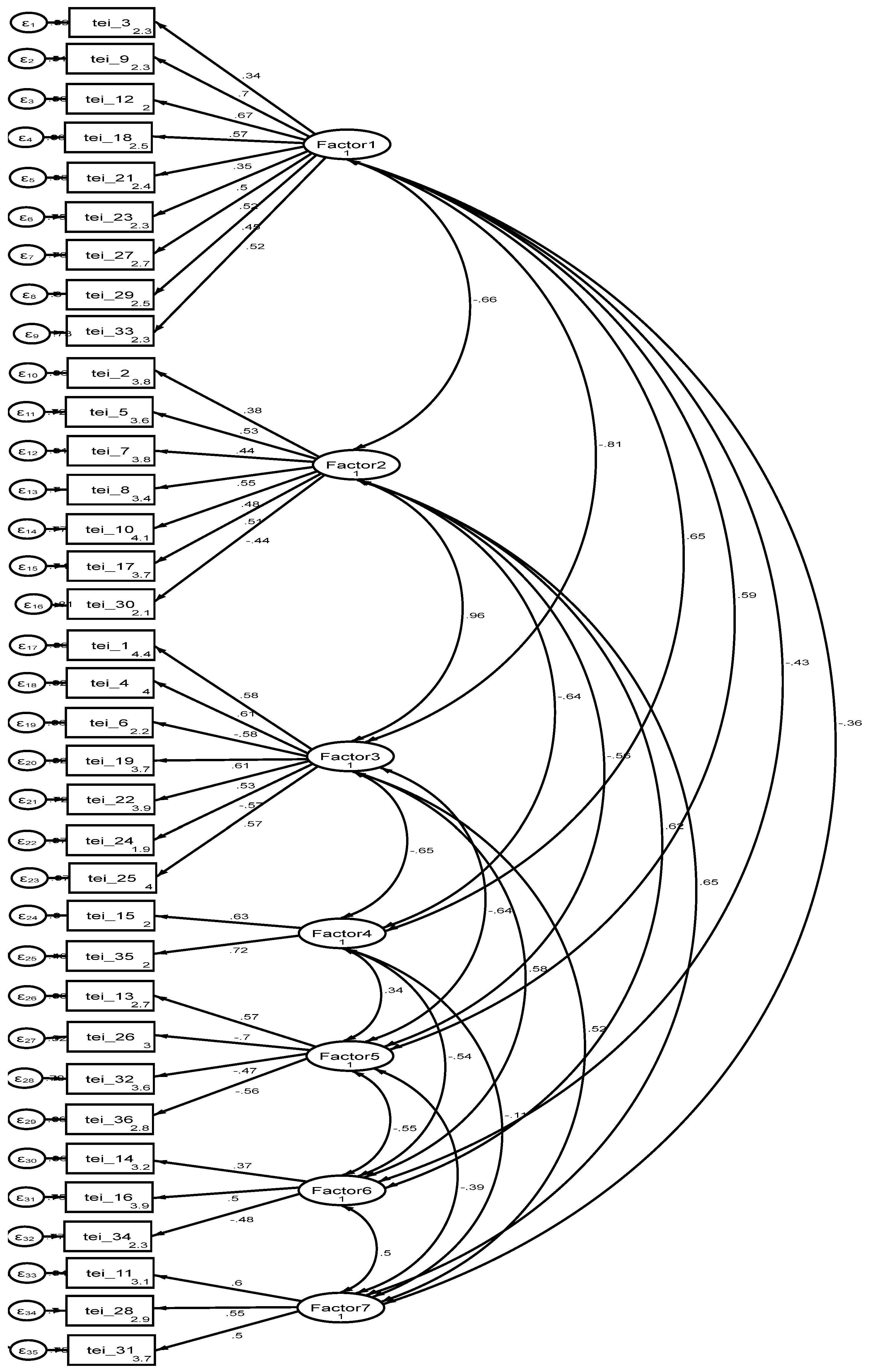

3. Results

3.1. Correlations Between Factors

3.2. Invariance Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. The Trait Emotional Intelligence Questionnaire (TEIQue) and Trait Emotional Intelligence Questionnaire-Sort Form (TEIQue-SF) in the Adult Population

4.2. Child and Adolescent Versions of the TEIQue

4.3. Limitations of the Study

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Al-Dassean, K. A. (2023). Psychometric properties of the Arabic version of the Trait Emotional Intelligence Questionnaire Short Form (TEIQue-SF). Cogent Psychology, 10(1), 2171184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aluja, A., Blanch, A., & Petrides, K. V. (2016). Psychometric properties of the Catalan version of the Trait Emotional Intelligence (TEIQue): Comparison between Catalan and English data. Personality and Individual Differences, 99, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentler, P. M. (1992). On the fit of models to covariances and methodology to the Bulletin. Psychological Bulletin, 112(3), 400–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beyazıt, U., Yurdakul, Y., & Ayhan, A. B. (2020). The psychometric properties of the Turkish version of the Trait Emotional Intelligence Questionnaire–Child Form. SAGE Open, 10(2), 215824402092290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chirumbolo, A., Picconi, L., Morelli, M., & Petrides, K. V. (2019). The assessment of trait emotional intelligence: Psychometric characteristics of the TEIQue-Full Form in a large Italian adult sample. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 2786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feher, A., Yan, G., Saklofske, D. H., Plouffe, R. A., & Gao, Y. (2019). An investigation of the psychometric properties of the Chinese trait emotional intelligence questionnaire short form (Chinese TEIQue-SF). Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freudenthaler, H. H., Neubauer, A. C., Gabler, P., Scherl, W. G., & Rindermann, H. (2008). Testing and validating the Trait Emotional Intelligence Questionnaire (TEIQue) in a German-speaking sample. Personality and Individual Differences, 45(7), 673–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gökçen, E., Furnham, A., Mavroveli, S., & Petrides, K. V. (2014). A cross-cultural investigation of trait emotional intelligence in Hong Kong and the UK. Personality and Individual Differences, 65, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenspoon, P. J., & Saklofske, D. H. (1998). Confirmatory factor analysis of the Multidimensional Students’ Life Satisfaction Scale. Personality and Individual Differences, 25(5), 965–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indices in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6(1), 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikolajczak, M., Luminet, O., Leroy, C., & Roy, E. (2007). Psychometric properties of the Trait Emotional Intelligence Questionnaire: Factor structure, reliability, construct, and incremental validity in a French-speaking population. Journal of Personality Assessment, 88(3), 338–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, R. O. (2012). Basic principles of structural equation modeling: An introduction to LISREL and EQS. Springer Science & Business Media. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, Q. A. N., Tran, T., Tran, T. A., Nguyen, T. V., & Fisher, J. (2025). Validation of the trait emotional intelligence questionnaire–Adolescent short form (TEIQue-ASF) among adolescents in Vietnam. SSM-Mental Health, 7, 100413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perazzo, M. F., Abreu, L. G., Pérez-Díaz, P. A., Petrides, K. V., Granville-Garcia, A. F., & Paiva, S. M. (2021). Trait Emotional Intelligence Questionnaire-Short Form: Brazilian validation and measurement invariance between the United Kingdom and Latin-American datasets. Journal of Personality Assessment, 103(3), 342–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrides, K. V., Pita, R., & Kokkinaki, F. (2016). The location of trait emotional intelligence in personality factor space. British Journal of Psychology, 98(2), 273–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, P. M., Mancini, G., Trombini, E., Baldaro, B., Mavroveli, S., & Petrides, K. V. (2012). Trait Emotional Intelligence and the Big Five: A study on Italian children and preadolescents. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 30(3), 274–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Ruiz, M., Mavroveli, S., & Petrides, K. V. (2021). The Trait Emotional Intelligence Questionnaire in Lebanon and the UK: A comparison of the psychometric properties in each country. International Journal of Psychology, 56(3), 304–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stamatopoulou, M., Galanis, P., & Prezerakos, P. (2016). Psychometric properties of the Greek translation of the Trait Emotional Intelligence Questionnaire-Short Form (TEIQue-SF). Personality and Individual Differences, 95, 80–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stassart, C., Etienne, A.-M., Luminet, O., Kaïdi, I., & Lahaye, M. (2019). The psychometric properties of the French version of the Trait Emotional Intelligence Questionnaire–Child Short Form. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 37(3), 293–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczygieł, D., Buczny, J., & Bazińska, R. (2015). Trait Emotional Intelligence and social functioning: A study on Polish adults. Personality and Individual Differences, 81, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulutaş, İ. (2019). Psychometric properties of the Trait Emotional Intelligence Questionnaire (TEIQue) in Turkish. Current Psychology, 38, 775–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuanazzi, A. C., Meyer, G. J., Petrides, K. V., & Miguel, F. K. (2022). Validity of the Trait Emotional Intelligence Questionnaire (TEIQue) in a Brazilian sample. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 735934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| n = 614 | n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Children’s characteristics | Gender | Girls | 334 (54.4) |

| Boys | 280 (45.6) | ||

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 10 (1.5) | ||

| BMI | Underweight | 14 (2.3) | |

| Normal | 381 (62.1) | ||

| Overweight | 183 (29.8) | ||

| Obese | 36 (5.9) | ||

| Greek nationality | 595 (96.9) | ||

| Parental characteristics | Parents’ gender | ||

| Women | 472 (76.9) | ||

| Men | 142 (23.1) | ||

| Parents’ age, mean (SD) | 41.8 (5.3) | ||

| Maximum parental educational level | |||

| High school at most | 198 (32.2) | ||

| Technical university | 138 (22.5) | ||

| University | 133 (21.7) | ||

| MSc | 110 (17.9) | ||

| PhD | 35 (5.7) | ||

| Married parents | 564 (91.9) | ||

| Socioeconomic status | |||

| Low | 15 (2.4) | ||

| Moderate | 224 (36.5) | ||

| High | 375 (61.1) | ||

| Completely Disagree | Disagree | Neutral | Agree | Completely Agree | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) |

| 1. | 6 (1) | 37 (6) | 95 (15.5) | 302 (49.2) | 174 (28.3) |

| 2. | 10 (1.6) | 44 (7.2) | 147 (23.9) | 249 (40.6) | 164 (26.7) |

| 3. | 116 (18.9) | 183 (29.8) | 134 (21.8) | 130 (21.2) | 51 (8.3) |

| 4. | 16 (2.6) | 33 (5.4) | 127 (20.7) | 233 (37.9) | 205 (33.4) |

| 5. | 26 (4.2) | 63 (10.3) | 99 (16.1) | 312 (50.8) | 114 (18.6) |

| 6. | 160 (26.1) | 232 (37.8) | 134 (21.8) | 74 (12.1) | 14 (2.3) |

| 7. | 24 (3.9) | 54 (8.8) | 150 (24.4) | 243 (39.6) | 143 (23.3) |

| 8. | 23 (3.7) | 89 (14.5) | 163 (26.5) | 237 (38.6) | 102 (16.6) |

| 9. | 115 (18.7) | 189 (30.8) | 154 (25.1) | 122 (19.9) | 34 (5.5) |

| 10. | 12 (2) | 42 (6.8) | 107 (17.4) | 284 (46.3) | 169 (27.5) |

| 11. | 45 (7.3) | 72 (11.7) | 163 (26.5) | 235 (38.3) | 99 (16.1) |

| 12. | 204 (33.2) | 193 (31.4) | 119 (19.4) | 70 (11.4) | 28 (4.6) |

| 13. | 62 (10.1) | 124 (20.2) | 191 (31.1) | 166 (27) | 71 (11.6) |

| 14. | 41 (6.7) | 59 (9.6) | 186 (30.3) | 214 (34.9) | 114 (18.6) |

| 15. | 183 (29.8) | 162 (26.4) | 139 (22.6) | 96 (15.6) | 34 (5.5) |

| 16. | 19 (3.1) | 30 (4.9) | 117 (19.1) | 234 (38.1) | 214 (34.9) |

| 17. | 16 (2.6) | 42 (6.8) | 209 (34) | 225 (36.6) | 122 (19.9) |

| 18. | 72 (11.7) | 157 (25.6) | 156 (25.4) | 154 (25.1) | 75 (12.2) |

| 19. | 19 (3.1) | 41 (6.7) | 100 (16.3) | 217 (35.3) | 237 (38.6) |

| 20. | 71 (11.6) | 120 (19.5) | 184 (30) | 181 (29.5) | 58 (9.4) |

| 21. | 84 (13.7) | 130 (21.2) | 133 (21.7) | 173 (28.2) | 94 (15.3) |

| 22. | 17 (2.8) | 33 (5.4) | 107 (17.4) | 238 (38.8) | 219 (35.7) |

| 23. | 95 (15.5) | 153 (24.9) | 135 (22) | 141 (23) | 90 (14.7) |

| 24. | 234 (38.1) | 198 (32.2) | 97 (15.8) | 57 (9.3) | 28 (4.6) |

| 25. | 11 (1.8) | 35 (5.7) | 103 (16.8) | 268 (43.6) | 197 (32.1) |

| 26. | 33 (5.4) | 106 (17.3) | 212 (34.5) | 172 (28) | 91 (14.8) |

| 27. | 60 (9.8) | 202 (32.9) | 184 (30) | 111 (18.1) | 57 (9.3) |

| 28. | 37 (6) | 103 (16.8) | 185 (30.1) | 195 (31.8) | 94 (15.3) |

| 29. | 77 (12.5) | 168 (27.4) | 160 (26.1) | 142 (23.1) | 67 (10.9) |

| 30. | 162 (26.4) | 185 (30.1) | 132 (21.5) | 93 (15.1) | 42 (6.8) |

| 31. | 17 (2.8) | 47 (7.7) | 104 (16.9) | 241 (39.3) | 205 (33.4) |

| 32. | 21 (3.4) | 64 (10.4) | 139 (22.6) | 221 (36) | 169 (27.5) |

| 33. | 113 (18.4) | 185 (30.1) | 180 (29.3) | 99 (16.1) | 37 (6) |

| 34. | 128 (20.8) | 171 (27.9) | 161 (26.2) | 111 (18.1) | 43 (7) |

| 35. | 179 (29.2) | 192 (31.3) | 104 (16.9) | 115 (18.7) | 24 (3.9) |

| 36. | 48 (7.8) | 112 (18.2) | 230 (37.5) | 149 (24.3) | 75 (12.2) |

| Component | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item | Emotional Regulation | Sociability | Positive Mood | Lack of Persistence | Low Impulsivity | Emotion Perception | Adaptability |

| 3. | 0.45 | ||||||

| 9. | 0.70 | ||||||

| 12. | 0.50 | ||||||

| 18. | 0.63 | ||||||

| 21. | 0.43 | ||||||

| 23. | 0.51 | ||||||

| 27. | 0.66 | ||||||

| 29. | 0.60 | ||||||

| 33. | 0.60 | ||||||

| 2. | 0.59 | ||||||

| 5. | 0.55 | ||||||

| 7. | 0.53 | ||||||

| 8. | 0.54 | ||||||

| 10. | 0.61 | ||||||

| 17. | 0.46 | ||||||

| 30. | −0.44 | ||||||

| 1. | 0.54 | ||||||

| 4. | 0.67 | ||||||

| 6. | −0.43 | ||||||

| 19. | 0.42 | ||||||

| 22. | 0.68 | ||||||

| 24. | −0.50 | ||||||

| 25. | 0.52 | ||||||

| 15. | 0.77 | ||||||

| 20. | 0.45 | ||||||

| 35. | 0.64 | ||||||

| 13. | −0.56 | ||||||

| 26. | 0.77 | ||||||

| 32. | 0.41 | ||||||

| 36. | 0.76 | ||||||

| 14. | 0.44 | ||||||

| 16. | 0.57 | ||||||

| 34. | −0.63 | ||||||

| 11. | 0.70 | ||||||

| 28. | 0.46 | ||||||

| 31. | 0.47 | ||||||

| %Variance explained | 10.7 | 9.2 | 9.1 | 6.4 | 6.0 | 5.7 | 5.3 |

| Factor | Item | Corrected Item–Total Correlation | Cronbach’s Alpha If Item Deleted | Cronbach’s Alpha |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emotional regulation | 3. | 0.32 | 0.81 | 0.80 |

| The ability to manage and control your emotional responses in different situations. | 9. | 0.67 | 0.76 | |

| 12. | 0.54 | 0.78 | ||

| 18. | 0.53 | 0.78 | ||

| 21. | 0.40 | 0.80 | ||

| 23. | 0.41 | 0.80 | ||

| 27. | 0.57 | 0.77 | ||

| 29. | 0.47 | 0.79 | ||

| 33. | 0.58 | 0.77 | ||

| Sociability | 2. | 0.44 | 0.68 | 0.71 |

| The tendency to enjoy being with and interacting with other people. | 5. | 0.40 | 0.69 | |

| 7. | 0.44 | 0.68 | ||

| 8. | 0.51 | 0.66 | ||

| 10. | 0.44 | 0.68 | ||

| 17. | 0.41 | 0.68 | ||

| 30. | 0.35 | 0.71 | ||

| Positive mood | 1. | 0.43 | 0.74 | 0.76 |

| A temporary emotional state of feeling happy, calm, or optimistic. | 4. | 0.56 | 0.71 | |

| 6. | 0.42 | 0.74 | ||

| 19. | 0.57 | 0.71 | ||

| 22. | 0.47 | 0.73 | ||

| 24. | 0.38 | 0.75 | ||

| 25. | 0.52 | 0.72 | ||

| Lack of persistence | 15. | 0.41 | 0.16 | 0.48 |

| The tendency to give up easily and not continue working toward goals. | 20. | 0.09 | 0.69 | |

| 35. | 0.43 | 0.14 | ||

| Low impulsivity | 13. | 0.50 | 0.66 | 0.72 |

| The ability to think before acting and resist sudden urges or temptations. | 26. | 0.62 | 0.59 | |

| 32. | 0.40 | 0.72 | ||

| 36. | 0.51 | 0.65 | ||

| Emotion perception | 14. | 0.46 | 0.56 | 0.71 |

| The ability to recognize and understand others’ feelings through facial expressions, tone of voice, or body language. | 16. | 0.32 | 0.74 | |

| 34. | 0.50 | 0.49 | ||

| Adaptability | 11. | 0.38 | 0.50 | 0.62 |

| The ability to adjust easily to new situations, changes, or challenges. | 28. | 0.37 | 0.51 | |

| 31. | 0.33 | 0.59 |

| Pearson’s Correlation Coefficient | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor | No. of Items | Mean | SD | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | |

| 1. | Emotional regulation | 9 | 3.22 | 0.72 | 1.00 | 0.45 | 0.56 | −0.40 | 0.47 | 0.35 | 0.31 |

| 2. | Sociability | 7 | 3.69 | 0.61 | 1.00 | 0.61 | −0.32 | 0.29 | 0.44 | 0.42 | |

| 3. | Positive mood | 7 | 3.93 | 0.66 | 1.00 | −0.43 | 0.45 | 0.36 | 0.39 | ||

| 4. | Lack of persistence | 2 | 2.39 | 1.05 | 1.00 | −0.24 | −0.29 | −0.12 | |||

| 5. | Low impulsivity | 4 | 3.27 | 0.79 | 1.00 | 0.30 | 0.30 | ||||

| 6. | Emotion perception | 3 | 3.61 | 0.79 | 1.00 | 0.29 | |||||

| 7. | Adaptability | 3 | 3.57 | 0.75 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Gender | BMI | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Girls | Boys | Underweight/Normal | Overweight/Obese | |||||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | P Student’s t-Test | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | P Student’s t-Test | |

| Emotional regulation | 3.31 | 0.71 | 3.12 | 0.73 | 0.001 | 3.35 | 0.68 | 2.98 | 0.74 | <0.001 |

| Sociability | 3.78 | 0.58 | 3.58 | 0.63 | <0.001 | 3.77 | 0.54 | 3.53 | 0.70 | <0.001 |

| Positive mood | 3.99 | 0.62 | 3.86 | 0.69 | 0.018 | 4.02 | 0.58 | 3.77 | 0.75 | <0.001 |

| Lack of persistence | 2.34 | 1.03 | 2.45 | 1.06 | 0.182 | 2.24 | 1.00 | 2.65 | 1.09 | <0.001 |

| Low impulsivity | 3.34 | 0.82 | 3.18 | 0.75 | 0.013 | 3.40 | 0.79 | 3.04 | 0.75 | <0.001 |

| Emotion perception | 3.66 | 0.78 | 3.55 | 0.80 | 0.076 | 3.72 | 0.78 | 3.42 | 0.78 | <0.001 |

| Adaptability | 3.58 | 0.74 | 3.56 | 0.77 | 0.762 | 3.62 | 0.74 | 3.48 | 0.76 | 0.038 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ferentinou, E.; Koutelekos, I.; Evangelou, E.; Zartaloudi, A.; Theodoratou, M.; Dafogianni, C. Psychometric Validation of the Trait Emotional Intelligence Questionnaire-Child Short Form (TEIQue-CSF) in a Greek Population. Psychol. Int. 2025, 7, 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/psycholint7030075

Ferentinou E, Koutelekos I, Evangelou E, Zartaloudi A, Theodoratou M, Dafogianni C. Psychometric Validation of the Trait Emotional Intelligence Questionnaire-Child Short Form (TEIQue-CSF) in a Greek Population. Psychology International. 2025; 7(3):75. https://doi.org/10.3390/psycholint7030075

Chicago/Turabian StyleFerentinou, Eftychia, Ioannis Koutelekos, Eleni Evangelou, Afroditi Zartaloudi, Maria Theodoratou, and Chrysoula Dafogianni. 2025. "Psychometric Validation of the Trait Emotional Intelligence Questionnaire-Child Short Form (TEIQue-CSF) in a Greek Population" Psychology International 7, no. 3: 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/psycholint7030075

APA StyleFerentinou, E., Koutelekos, I., Evangelou, E., Zartaloudi, A., Theodoratou, M., & Dafogianni, C. (2025). Psychometric Validation of the Trait Emotional Intelligence Questionnaire-Child Short Form (TEIQue-CSF) in a Greek Population. Psychology International, 7(3), 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/psycholint7030075