Induced After-Death Communication (IADC) Experience and Near-Death Experience (NDE): Two Variations of a Single Phenomenon

Abstract

1. Introduction

- The phenomenon of natural after-death communication (ADC)—communication that occurs outside a therapeutic context—has been the subject of extensive research and documentation due to its potentially beneficial impact on the grieving process.

- The development of induced after-death communication (IADC) therapy has enabled the facilitation of such spontaneous experiences in individuals diagnosed with Prolonged Grief Disorder.

- Advances in resuscitation techniques since the late 1960s have made it possible to revive a greater number of individuals whose hearts had ceased functioning. This development has led to a rise in first-person reports of near-death experiences (NDEs), giving rise to a new line of scientific inquiry.

- Concurrently, clinical observations have highlighted notable phenomenological similarities between IADC experiences (as distinct from natural ADC) and NDEs, despite the differing conditions under which they occur. However, no empirical study has yet systematically investigated whether IADC experiences meet the phenomenological criteria commonly recognized for identifying NDEs.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Measures

2.5. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

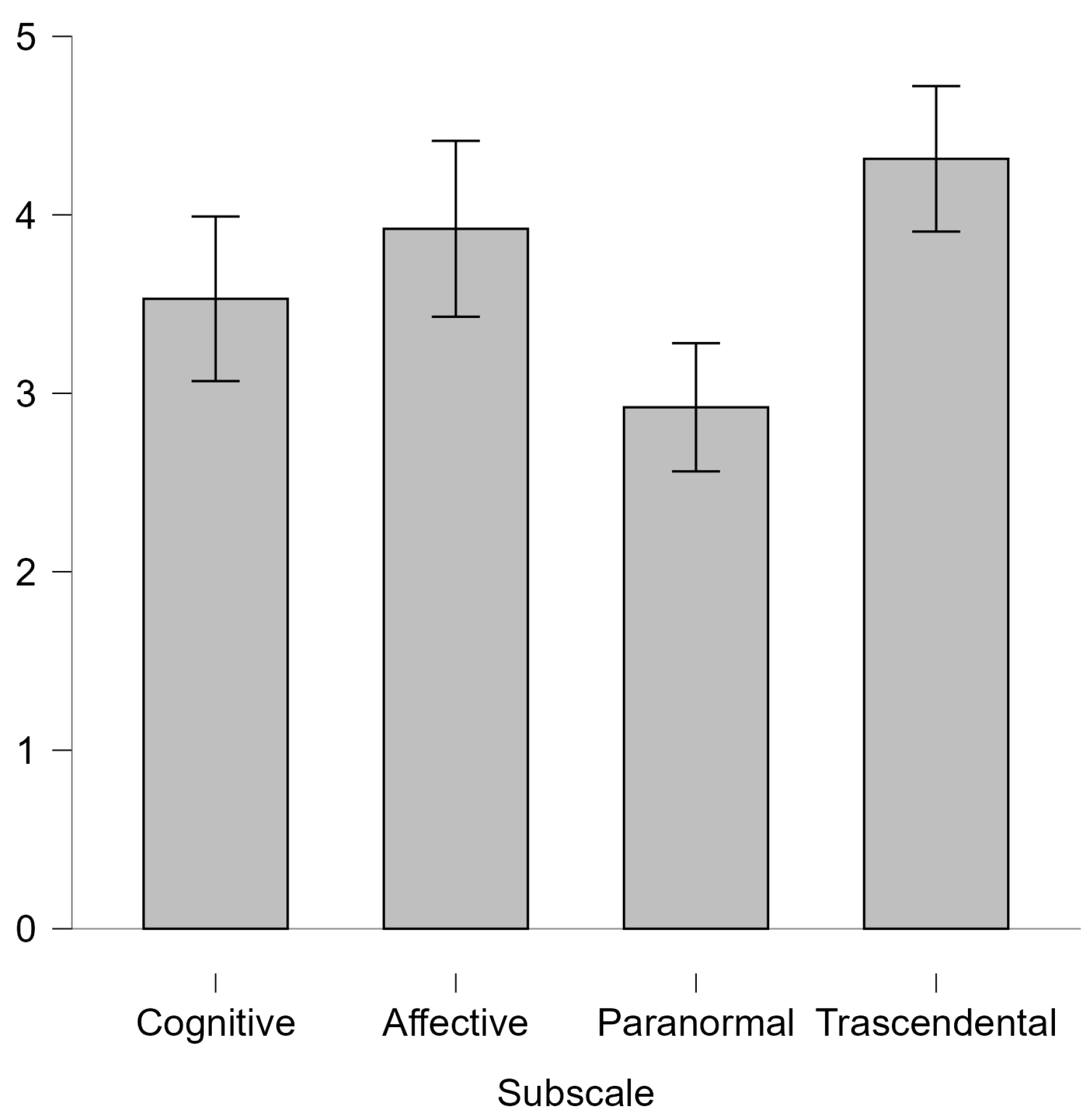

3.1. Comparative Analysis of NDE Subscales

3.2. Post Hoc Pairwise Comparisons

3.3. Item-Level Analysis of Experiential Intensity

4. Discussion

4.1. Phenomenological Overlap Between IADC and NDEs

4.2. Item-Level Intensity on the NDE Scale in IADC Experiences

4.3. Study Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| IADC | Induced After Death Communication |

| NDE | Near-Death Experiences |

| EMDR | Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing |

References

- Belanti, J., Perera, M., & Jagadheesan, K. (2008). Phenomenology of near-death experiences: A cross-cultural perspective. Transcultural Psychiatry, 45(1), 121–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Botkin, A. L. (2000). The induction of after-death communications utilizing eye-movement desensitization and reprocessing: A new discovery. Journal of Near-Death Studies, 18(3), 181–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botkin, A. L., & Hannah, M. T. (2013). Brief report: Psychotherapeutic outcomes reported by therapists trained in induced after-death communication. Journal of Near-Death Studies, 31(4), 221–224. [Google Scholar]

- Botkin, A. L., & Hogan, R. C. (2005). Induced after-death communication: A new therapy for healing grief and traumatic loss. Hampton Roads Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby, J. (1980). Attachment and loss: Vol. 3. Loss: Sadness and depression. Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Brennan, M. J. (2014). The A–Z of death and dying: Social, medical, and cultural aspects. Greenwood. [Google Scholar]

- Carifio, J., & Perla, R. (2008). Resolving the 50-year debate around using and misusing Likert scales. Medical Education, 42(12), 1150–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Antoni, F., Pulvirenti, I., D’Orlando, A., Claudio, V., & Lalla, C. (2025). Induced after-death communication (IADC) therapy: An effective and quick intervention to cope with grief. Psychology International, 7(1), 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsaesser, E. (2023). Spontaneous contacts with the deceased: A large-scale international survey reveals the circumstances, lived experience and beneficial impact of after-death communications (ADCs). Iff Books. [Google Scholar]

- Fenwick, P., & Fenwick, E. (2008). The art of dying. Continuum. [Google Scholar]

- Freud, S. (1917). Mourning and melancholia. In The standard edition of the complete psychological works of sigmund freud (Vol. 14, pp. 243–258). Hogarth Press. [Google Scholar]

- Greyson, B. (1983). The near-death experience scale: Construction, reliability, and validity. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 171(6), 369–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greyson, B. (2003). Incidence and correlates of near-death experiences in a cardiac care unit. General Hospital Psychiatry, 25(4), 269–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guggenheim, B., & Guggenheim, J. (1996). Hello from heaven! A new field of research confirms that life and love are eternal. Bantam. [Google Scholar]

- Hannah, M. T., Botkin, A. L., Marrone, J. G., & Streit-Horne, J. (2013). Induced after-death communication: An update. Journal of Near-Death Studies, 31(4), 213–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holden, J. M. (2017). After-death communication. In R. D. Foster, & J. M. Holden (Eds.), Connecting: Soul, spirit, mind, and body (pp. 3–11). Aquiline Books. [Google Scholar]

- Holden, J. M., Greyson, B., & James, D. (Eds.). (2009). The handbook of near-death experiences: Thirty years of investigation. Praeger/ABC-CLIO. [Google Scholar]

- Holden, J. M., St. Germain-Sehr, N. R., Reyes, A., Loseu, S., Schmit, M. K., Laird, A., Weintraub, L., St. Germain-Sehr, A., Price, E., Blalock, S., Bevly, C., Lankford, C., & Mandalise, J. (2019). Comparative effects of induced after-death communication and traditional talk therapy on grief. Grief Matters: The Australian Journal of Grief and Bereavement, 22(1), 4–9. [Google Scholar]

- Klass, D., Silverman, P. R., & Nickman, S. L. (1996). Continuing bonds: New understandings of grief. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Klass, D., & Steffen, M. (Eds.). (2018). Continuing bonds in bereavement: New directions for research and practice. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Knoblauch, H., Schmied, I., & Schnettler, B. (2001). Different kinds of near-death experience: A report on a survey of near-death experiences in Germany. Journal of Near-Death Studies, 20(1), 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaGrand, L. E. (1997). After-death communication: Final farewells. Llewellyn. [Google Scholar]

- Lalla, C. (2021). Perdita e ricongiungimento: Comunicare con i propri cari oltre il tempo della loro vita. Edizioni Mediterranee. [Google Scholar]

- Long, J., & Perry, P. (2010). Evidence of the afterlife: The science of near-death experiences. HarperOne. [Google Scholar]

- Martial, C., Simon, J., Puttaert, N., Gosseries, O., Charland-Verville, V., Nyssen, A. S., Greyson, B., Laureys, S., & Cassol, H. (2020). The Near-Death Experience Content (NDE-C) scale: Development and psychometric validation. Consciousness and Cognition, 86, 103049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moody, R. A. (1975). Life after life. Mockingbird Books. [Google Scholar]

- Neimeyer, R. A. (Ed.). (2023). New techniques of grief therapy: Bereavement and beyond (2nd ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Norman, G. (2010). Likert scales, levels of measurement and the “laws” of statistics. Advances in Health Sciences Education, 15(5), 625–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pait, K. C., Exline, J. J., Pargament, K. I., & Zarrella, P. (2023). After-death communication: Issues of nondisclosure and implications for treatment. Religions, 14(8), 985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkes, C. M. (1970). Bereavement: Studies of grief in adult life. International Universities Press. [Google Scholar]

- Parnia, S., Post, S. G., Lee, M. T., Lyubomirsky, S., Aufderheide, T. P., Deakin, C. D., Greyson, B., Long, J., Gonzales, A. M., Huppert, E. L., Dickinson, A., Mayer, S., Locicero, B., Levin, J., Bossis, A., Worthington, E., Fenwick, P., & Shirazi, T. K. (2022). Guidelines and standards for the study of death and recalled experiences of death: A multidisciplinary consensus statement and proposed future directions. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1511(1), 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Penberthy, J. K., Pehlivanova, M., Kalelioglu, T., Roe, C. A., Cooper, C. E., Lorimer, D., & Elsaesser, E. (2023). Factors moderating the impact of after-death communications on beliefs and spirituality. OMEGA—Journal of Death and Dying, 87(3), 884–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perera, M., Padmasekara, G., & Belanti, J. (2005). Prevalence of near-death experiences in Australia. Journal of Near-Death Studies, 24(2), 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pistoia, F., Mattiacci, G., Sarà, M., Padua, L., Macchi, C., & Sacco, S. (2018). Development of the Italian version of the Near-Death Experience Scale. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 12, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ring, K. (1984). Heading toward Omega: In search of the meaning of the near-death experience. William Morrow. [Google Scholar]

- Sabom, M. (1998). Light and death. Zondervan. [Google Scholar]

- Schwaninger, J., Eisenberg, P. R., Schechtman, K. B., & Weiss, A. N. (2002). A prospective analysis of near-death experiences in cardiac arrest patients. Journal of Near-Death Studies, 20(4), 215–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, F. (1989a). Efficacy of the eye movement desensitization procedure in the treatment of traumatic memories. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 2, 199–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, F. (1989b). Eye movement desensitization: A new treatment for post-traumatic stress disorder. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 20, 211–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sormanti, M., & August, J. (1997). Parental bereavement: Spiritual connections with deceased children. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 67(3), 460–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- St. Germain-Sehr, N. R., & Maxey, G. A. (2019). Case studies in induced after death communication. Grief Matters—The Australian Journal of Grief and Bereavement, 22, 18–21. [Google Scholar]

- Streit-Horne, J. (2011). A Systematic review of research on After-Death Communications (ADC) [Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy, University of North Texas]. [Google Scholar]

- van Lommel, P. (2007). Consciousness beyond life: The science of the near-death experience. HarperCollins. [Google Scholar]

- van Lommel, P., van Wees, R., Meyers, V., & Elfferich, I. (2001). Near-death experience in survivors of cardiac arrest: A prospective study in The Netherlands. The Lancet, 358(9298), 2039–2045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Worden, J. W. (2018). Grief counseling and grief therapy: A handbook for the mental health practitioner (5th ed.). Springer. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | Category | N | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | M = 56.25, SD = 10.18 | ||

| Time since last IADC session (months) | M = 37.09, SD = 32.27 | ||

| Gender | |||

| Male | 6 | 10% | |

| Female | 53 | 90% | |

| Marital Status | |||

| Married | 19 | 32% | |

| Single | 8 | 14% | |

| Widowed | 13 | 22% | |

| Divorced | 5 | 8% | |

| Separated | 5 | 8% | |

| Cohabiting | 9 | 15% | |

| Educational Attainment | |||

| Lower Secondary School | 4 | 7% | |

| High School Diploma | 12 | 20% | |

| Bachelor’s Degree | 6 | 10% | |

| Master’s Degree | 28 | 47% | |

| Postgraduate Specialization | 6 | 10% | |

| Doctorate | 3 | 5% | |

| Occupational Status | |||

| Employed | 45 | 76% | |

| Unemployed | 2 | 3% | |

| Retired | 10 | 17% | |

| Homemaker | 2 | 3% | |

| Religious Belief | |||

| Catholic/Other Religions | 34 | 58% | |

| Spiritual but not Religious | 22 | 37% | |

| Agnostic | 2 | 3% | |

| Atheist | 1 | 2% | |

| Previous NDE | |||

| Yes | 5 | 8% | |

| No | 54 | 92% | |

| Previous Spontaneous ADC Experience | |||

| Yes | 35 | 59% | |

| No | 24 | 41% | |

| Primary Contact During IADC Session | Parent | 21 | 36% |

| Partner | 17 | 29% | |

| Offspring | 14 | 24% | |

| Extended Family | 3 | 5% | |

| Sibling | 2 | 3% | |

| Friend | 1 | 2% | |

| Pet | 1 | 2% |

| NDE Scale | Above Cut-Off (≥7) M (SD) | Below Cut-Off (<7) M (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Total Score | 14.69 (5.16) | 4.00 (1.51) |

| Subscales | ||

| Cognitive | 3.53 (1.71) | 0.63 (0.74) |

| Affective | 3.92 (2.28) | 1.38 (0.92) |

| Paranormal | 2.92 (1.73) | 0.63 (0.74) |

| Transcendental | 4.31 (1.63) | 1.38 (0.92) |

| Mean Difference | SE | Cohen’s d | pHolm | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cognitive | Affective | −0.39 | 0.32 | −0.21 | 0.46 |

| Paranormal | 0.61 | 0.30 | 0.33 | 0.14 | |

| Transcendental | −0.78 | 0.33 | −0.42 | 0.08 | |

| Affective | Paranormal | 1.00 | 0.32 | 0.54 | 0.02 |

| Transcendental | −0.39 | 0.34 | −0.21 | 0.46 | |

| Paranormal | Transcendental | −1.39 | 0.21 | −0.75 | <0.001 |

| Item | 0 | 1 | 2 | Mean | SD | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Freq. | % | Freq. | % | Freq. | % | |||

| NDE01 | 21 | 41% | 17 | 33% | 13 | 25% | 0.843 | 0.809 |

| NDE02 | 9 | 18% | 31 | 61% | 11 | 22% | 1.039 | 0.631 |

| NDE03 | 20 | 39% | 19 | 37% | 12 | 24% | 0.843 | 0.784 |

| NDE04 | 22 | 43% | 17 | 33% | 12 | 24% | 0.804 | 0.8 |

| NDE05 | 5 | 10% | 35 | 69% | 11 | 22% | 1.118 | 0.553 |

| NDE06 | 19 | 37% | 15 | 29% | 17 | 33% | 0.961 | 0.848 |

| NDE07 | 21 | 41% | 14 | 27% | 16 | 31% | 0.902 | 0.855 |

| NDE08 | 19 | 37% | 16 | 31% | 16 | 31% | 0.941 | 0.835 |

| NDE09 | 8 | 16% | 31 | 61% | 12 | 24% | 1.078 | 0.627 |

| NDE10 | 19 | 37% | 13 | 25% | 19 | 37% | 1.0 | 0.872 |

| NDE11 | 44 | 86% | 3 | 6% | 4 | 8% | 0.216 | 0.577 |

| NDE12 | 27 | 53% | 16 | 31% | 8 | 16% | 0.627 | 0.747 |

| NDE13 | 7 | 14% | 18 | 35% | 26 | 51% | 1.373 | 0.72 |

| NDE14 | 22 | 43% | 7 | 14% | 22 | 43% | 1.0 | 0.938 |

| NDE15 | 6 | 12% | 15 | 29% | 30 | 59% | 1.471 | 0.703 |

| NDE16 | 37 | 73% | 4 | 8% | 10 | 20% | 0.471 | 0.809 |

| Experience Intensity Level | Mean Score Range | Response Distributions |

|---|---|---|

| Very High | ≥1.26 | Predominance of responses scoring 2 (distribution: 2 > 1 > 0). |

| High | 1.00–1.25 | Either: (a) predominance of responses scoring 1, followed by 2 (distribution: 1 > 2 > 0), or (b) a bimodal distribution in which responses scoring 0 and 2 exceed those scoring 1 with responses scoring 1 and 2 jointly exceeding 50% of total responses (distribution: 0 ≈ 2 > 1, with 1 + 2 > 50%). |

| Medium | 0.76–0.99 | Prevalence (but not predominance) of responses scoring 0, with responses scoring 1 and 2 jointly exceeding 50% of total responses (distribution: 0 > 2 > 1 or 0 > 1 > 2, with 1 + 2 > 50%). |

| Low | 0.50–0.75 | Predominance of responses scoring 0, followed by responses scoring 1 and few scoring 2 (distribution: 0 > 1 > 2). |

| Very Low | <0.50 | Predominance of responses scoring 0, with few responses scoring 1 and 2 (distribution: 0 ≫ 1 > 2 or 0 ≫ 2 > 1). |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lalla, C.; D’Antoni, F. Induced After-Death Communication (IADC) Experience and Near-Death Experience (NDE): Two Variations of a Single Phenomenon. Psychol. Int. 2025, 7, 66. https://doi.org/10.3390/psycholint7030066

Lalla C, D’Antoni F. Induced After-Death Communication (IADC) Experience and Near-Death Experience (NDE): Two Variations of a Single Phenomenon. Psychology International. 2025; 7(3):66. https://doi.org/10.3390/psycholint7030066

Chicago/Turabian StyleLalla, Claudio, and Fabio D’Antoni. 2025. "Induced After-Death Communication (IADC) Experience and Near-Death Experience (NDE): Two Variations of a Single Phenomenon" Psychology International 7, no. 3: 66. https://doi.org/10.3390/psycholint7030066

APA StyleLalla, C., & D’Antoni, F. (2025). Induced After-Death Communication (IADC) Experience and Near-Death Experience (NDE): Two Variations of a Single Phenomenon. Psychology International, 7(3), 66. https://doi.org/10.3390/psycholint7030066