Abstract

Traditionally, disaster research has focused on well-being consequences or socio-economic effects, often overlooking the association between disaster-brought life changes (i.e., transition) and mental health. Therefore, in this online longitudinal survey, we aimed to evaluate the long-term transitional impact of the flood in Western Germany and the wildfire in British Columbia, Canada, both of which happened during the summer of 2021. Additionally, we aimed to examine the relationships among these disaster-specific transitions and mental health, as well as feelings of being abandoned by the community and government. In this multi-site, multi-disaster study, 48 BC and 41 Western Germany adults were first assessed in 2021, then reassessed in 2022. During both waves, respondents completed the 12-item TIS, the 21-item DASS, the 8-item PCL, and the 2-item feeling of abandonment instrument (community and government). Results indicated that (a) the Germany flood produced higher material and psychological change in 2021 than in 2022; (b) the BC fire produced higher psychological change in 2021 than 2022, but produced modest material change in both time points; (c) the BC-fire group reported greater mental distress in 2021 than 2022, the Germany-flood group reported moderate-to-severe mental distress in both waves, and neither group experienced PTSD-like symptoms; (d) in both groups, evacuees experienced more change and distress than non-evacuees; (e) BC-fire evacuees and Germany-flood non-evacuees indicated that they felt more abandoned by their community than their government; and (f) over time, only psychological changes were reliably associated with distress in both groups. We speculated that following disasters, people’s mental health was largely shaped by the levels of disaster-induced life changes, particularly psychological changes that unfold over time.

1. Introduction

Natural disasters are unexpected, large-scale events that disrupt social life, cause collective distress, and harm economic conditions; they do this by damaging infrastructure, closing businesses, and interrupting education and utility services (Neria et al., 2008; Norris et al., 2002; Goldmann & Galea, 2014; Tremblay et al., 2006). Currently, the prevalence and magnitude of natural disasters have increased, and they affect people’s socio-economic and mental-health conditions (Eisenman & Galway, 2022; Zhong et al., 2018; Cianconi et al., 2020). Prior research indicates individual variability in mental-health outcomes after disaster exposure (Norris et al., 2002; Bonanno & Gupta, 2009; Goldmann & Galea, 2014). To elaborate, although most people adapt effectively in the aftermath of a disaster, a considerable portion undergo psychological distress, and a minor portion develop serious mental illness (Norris et al., 2009; Bonanno et al., 2010). Therefore, it is important to recognize what makes some people vulnerable to the negative effects of disasters and not others. In this research, we intended to address these individual differences in mental-health outcomes by examining the consequences of different disasters. We did this because prior findings indicated that disaster effects are likely to vary based on the disaster types and the time elapsed since onset (Fussell et al., 2017; Raker, 2020). It is already known that, at least during their early stages, disasters typically change the lives of the people who experience them. However, little is known about how disasters change those lives, especially in the long run. Therefore, we were interested in understanding the nature and extent of life changes brought about by different disasters, the effect of a candidate disaster on mental health, and the extent of their relationship. Particularly, we sought to understand the long-term impact of different disaster types. Hence, the current study was driven by the purpose to determine the type and magnitude of disaster-induced life changes, well-being status, and the relationship between the two by looking into the consequences of various disasters over time. To achieve this goal, we selected central British Columbia, Canada, and Western Germany as our study sites. We selected these locations because of their distinct disaster features—the former is prone to seasonal wildfires, and the latter experiences only periodic flooding (Fekete & Sandholz, 2021; Copes-Gerbitz et al., 2022). However, in 2021, the wildfire in BC and the flood in Western Germany caused widespread destruction and left communities grappling with prolonged recovery.

In July 2021, Germany experienced its worst flood disaster since 1962 (Kühne et al., 2021). Followed by prolonged and heavy rainfall, the Western part of Germany, Rheinland–Palatinate, and North Rhein–Westphalia were hit by massive flooding. The most affected areas were around the rivers Ahr and Erft, particularly the Ahr valley, which was severely damaged (Lehmkuhl et al., 2022; Tradowsky et al., 2023). This flash flood resulted in the extensive destruction of residential, commercial, and industrial properties; it caused at least 180 deaths, 750 injuries, and caused thousands to experience financial hardship (Lehmkuhl et al., 2022; Tradowsky et al., 2023; Thieken et al., 2023).

Also in the summer of 2021, a record-breaking heatwave prompted a catastrophic wildfire in British Columbia, Canada, where parts of the province, that is, the town of Lytton in particular, were largely destroyed (Schiermeier, 2021; Coogan et al., 2022). The fire burned nearly 8700 square kilometers of land, left two dead, and displaced thousands, making it the third worst year on record after 2018 and 2017 (Kulkarni, 2021; Crowley et al., 2022). Prior findings indicated that disaster-affected individuals often experience increased feelings of emotional turmoil, negative well-being, and other significant psychosocial problems, and that these issues can linger for several years (Stanke et al., 2012; McFarlane, 1988; Parslow et al., 2005; Bryant et al., 2014). Therefore, to track how the flood in Western Germany and the fire in British Columbia affected the lives and well-being of the affected people over time, we conducted an online longitudinal survey, first immediately after the disasters, i.e., 2021, and then a year later, i.e., 2022.

Besides the physical impact, the mental health of individuals who suffered the loss of their homes, employment, family, and friends during a disaster represents a prolonged effect of the event (Kaniasty & Norris, 1993, 2008; Thieken et al., 2016; Hikichi et al., 2016). Although prior findings have recognized a variety of social, environmental, and financial conditions as possible reasons for mental-health issues following a disaster (Friedman, 2006; North, 2014; Morganstein & Ursano, 2020; Mao & Agyapong, 2021), there is still a gap in the understanding of how disaster-induced life changes, also known as transitions (i.e., material change, psychological change), relate to the mental-health consequences of the affected.

This project takes the Transition Theory (Brown, 2016; Brown et al., 2016) as its guiding framework. According to the Transition Theory, a transition is an event or a series of events that cause a fundamental and enduring change in the “fabric of daily life”—what people do, where they do it, and with whom (Brown, 2016). Put differently, important transitions put an abrupt end to one lifetime period and give rise to another (Brown et al., 2016). From this viewpoint, the 2021 flood in Germany and wildfire in BC may have brought about a transitional effect on the lives of some individuals impacted by fire and flooding. Also, besides impacting people’s material condition (e.g., activities, belongings, places, people), major transitions often affect their attitudes, thoughts, self-image, and emotions (Sarason et al., 1978; Wheaton, 1990; Tennant, 2002). Thus, it is important to record the changes (i.e., material change and psychological change) induced by the disaster-related transition from its start and observe as it unfolds.

Recently, the 12-item Transitional Impact Scale (TIS-12, Svob et al., 2014; Uzer, 2020) has been used to assess the effect of various transitional events on the lives of those who experienced them (Uzer & Brown, 2015; Shi & Brown, 2016; Gu et al., 2017; Uzer et al., 2020; Heanoy et al., 2021; Opriș et al., 2023). The TIS scale items independently assess the material and psychological impact of a candidate transition. For each item (e.g., “This event has changed the activities I engage in”), the participants choose a rating between 1 (completely disagree) to 5 (completely agree). Theoretically, a potential transitional event scoring greater than 3.0 (neutral) should be expected to bring at least a moderate change in an individual’s life (Svob et al., 2014).

Additionally, prior studies have demonstrated that life changes brought about by important transitional events can have a profound impact on people’s mental health (Holmes & Rahe, 1967; Wheaton, 1990; Rutter, 1996; Tennant, 2002). This would be especially true for disaster-generated life changes (e.g., disruption in their routine life, evacuation from their house and job, re-evaluation of belief and attitude), because people have to go through a post-disaster adjustment. This adjustment period could be emotionally exhausting, as it may include reconstructive and rebuilding activities such as renovating a house, dealing with insurance, and recovering belongings, etc. (Heanoy et al., 2023). Therefore, this pre-disaster to post-disaster transition could generate mental-health problems such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, anxiety, and stress (Goldmann & Galea, 2014; Stanke et al., 2012; Norris et al., 2002; Newnham et al., 2022). However, little research exists that focuses on what may be a crucial relationship between disaster-related changes (or transition) and mental health (Heanoy et al., 2023).

Finally, we note that there is still a dearth of research on the long-term effects of natural disasters (Neria et al., 2008; Norris et al., 2002; Newnham et al., 2022). This is problematic because a disaster’s negative consequences can extend, in some cases, over many years. The reason is that, in the aftermath, disaster-affected individuals typically attempt to rebuild their lives and re-establish personal, social, and financial connections, and these efforts often progress slowly (Kessler et al., 2008; Gibbs et al., 2013). Given that post-disaster adjustments can be challenging, it is critical to understand the delayed and gradual effects of these transitions to track these impacts on people’s mental health.

Given these facts, we were interested in examining the long-term transitional impact of the 2021 flood in Western Germany (Germany flood) and the 2021 fire in British Columbia, Canada (BC fire), and the mental-health consequences of these disasters. We were also interested in examining the link between the transitional impact and well-being outcome in the fire- and flood-affected groups, respectively.

Based on prior findings (Shi & Brown, 2016; Gu et al., 2017; Uzer et al., 2020; Kirkegaard Thomsen et al., 2021), we expected that, at the outset, both flood- and fire-affected individuals would provide at least a moderate TIS rating for material change. Specifically, those who experienced a major disruption in their daily lives, such as displacement or evacuation, should produce a high material-TIS score. For psychological change, we expected a psychological-TIS rating of no less than a moderate level, irrespective of the extent of material consequence (e.g., evacuation). This is because natural disasters are foreboding and anxiety-provoking for people in affected communities (Silove et al., 2007; Morganstein & Ursano, 2020; Berry et al., 2010). As for the long-term TIS results, we expected that, at the very least, material- and psychological-TIS scores would remain in accordance with the scores from the early phases of flood and fire (Ruch & Holmes, 1971; C. Lee & Gramotnev, 2007; Kim & Moen, 2002; Kralik et al., 2006; Holmes & Rahe, 1967).

Furthermore, the social and personal lives of some disaster-affected people may be disrupted because they experience relocation, financial instability, and house/property reconstruction. In turn, these post-disaster stressors may lead to mental-health issues (Tremblay et al., 2006; Kaniasty, 2012; Hrabok et al., 2020). However, these well-being issues might arise at the outset of the disasters, or at a later period (Anderson, 2009; Swim et al., 2011; Tunstall et al., 2006; Moosavi et al., 2019). Some research has indicated that in the aftermath, most of the disaster-impacted people do not develop mental-health issues, but rather return to their pre-disaster level of functioning (Galea et al., 2003; Breslau, 1998; Norris et al., 2009; Clayton, 2021). In contrast, other studies have found that following disasters, people can experience fluctuating stress-like symptoms (e.g., depression, anxiety, and/or PTSD; Bryant et al., 2013; Gibbs et al., 2013; Chen et al., 2020). Therefore, we anticipated that during the early stages, the disasters would have at least a moderate impact on the mental health of the people of BC and Germany, but, for the long-term well-being outcome, we had no firm predictions. On the one hand, individuals might experience profound distress shortly after the disaster, but with time, their mental health might improve (Galea et al., 2003). On the other hand, persistent mental problems might not lessen with time, and people could experience severe levels of anxiety, depression, and PTSD at various time points after the disaster (Bryant et al., 2013, 2014). This would occur if following the disasters, people had to contend with extended periods of evacuation and/or rebuilding, periods know to be so distressing that they can elevate levels of stress and anxiety to a pathological level (Gibbs et al., 2013; Bryant et al., 2013; Moosavi et al., 2019).

Given our understanding of the strong effect that major life transitions, even normative, predicable ones, have on mental health (Holmes & Rahe, 1967; Wheaton, 1990; Rutter, 1996; Tennant, 2002), we were interested in determining whether there would be a distinct connection among the disaster-induced material and psychological changes and poor mental-health consequences. We expected that, over time, there would be a consistently strong relationship between the disaster-induced changes and mental-health consequences for both the fire and flood (Heanoy et al., 2023).

In addition to the transitional impact of the fire and flood disasters and their effect on mental health, we were interested in how the respondents in each group felt about their respective community and governmental disaster response. We included questions regarding feelings of abandonment by the community and officials in order to explore whether indices of social cohesion were related to the transitional impact of the disasters and levels of depression, anxiety, stress, and PTSD. Note that prior findings indicate that people tend to have positive feelings toward their communities and negative feelings toward the government (DeYoung & Peters, 2016; Morgado, 2020). We expected to replicate this pattern in both samples and across waves.

In summary, in this longitudinal, multi-site study, we assessed the transitional impact of the 2021 BC fire and the German flood, the associated mental-health consequences of these disasters, the level of abandonment individuals in the affected communities and governments felt, and the relationship among these factors. Long-term follow-up assessment of natural disasters could help professionals develop strategic interventions to protect people’s well-being during disaster crises. These assessments could also aid policymakers in taking initiatives to promote resilience in the aftermath of disasters.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

This study employed a longitudinal design, focusing on two distinct groups—residents from British Columbia, Canada, and individuals from Western Germany. Data was collected at two time points (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Number of participants and participation timeline from Wave 1 to Wave 2. * Respondents who only participated in Wave 1 (Appendix A).

2.2. Participants

Initially, 122 residents from British Columbia, Canada, who experienced the wildfire of 2021, and 75 residents from Western Germany who went through the flood of 2021 completed a self-paced online survey (i.e., Google Forms). The first wave of data collection took place between September 2021 and December 2021, starting some 3 months after the fire and flood occurred. Participants from both regions were drawn from the general adult population. Wave 2 was initiated 12 months later with the same population, between September 2022 and October 2022. In the second wave, Wave 1 participants who indicated that they would be interested in taking part in a follow-up were sent the online survey form. One hundred and two of the Wave-1 BC-fire participants and 57 of the Wave-1 Germany-flood participants expressed interest in taking part in the follow-up. Thus, the Wave 2 data collection included only respondents who participated in Wave 1. In total, 48 BC-fire respondents and 41 Germany-flood respondents returned the completed survey form. The remaining participants (54 BC-fire people and 16 Germany-flood people) did not fill out the questionnaire. The lack of response could be attributed to the strictly voluntary participation without remuneration, as well as the possibility that some email addresses provided during Wave 1 were no longer active. Our current study focused on those 48 BC-fire and 41 Germany-flood respondents who participated in the first and second waves (Figure 1).

The sample size was not determined based on a priori power analysis. A separate post hoc power analysis using G*power (Faul et al., 2007; procedure: “t-test: linear multiple regression: fixed model, single regression coefficient”) was conducted for each dependent variable: depression, anxiety, stress, and PTSD, where independent variables of interest were material TIS and psychological TIS. With parameters set to a two-tailed test, five predictors, α = 0.05, and a total sample size of 89, an effect size (Cohen’s f2) ranging from 0.04 to 0.35 was detected. For most of the regression models, the observed power was ≥80%, except for the depression, anxiety, and stress model with the predictor material TIS (observed power 46%). Next, a sensitivity analysis was performed using G*power to determine the smallest effect size that could be reliably detected within the given sample. This analysis indicated that by keeping the same parameter with a statistical power of 80%, an effect size of f2 = 0.09 was detected.

Demographic characteristics of both samples are reported in Table 1. Descriptive data for the respondents who only participated in Wave 1 is listed in Appendix A.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of British Columbia (n = 48) and Western Germany (n = 41) samples.

3. Materials

3.1. Transitional Impact Scale

A modified version of the 12-item Transitional Impact Scale (Svob et al., 2014, Supplementary File S1) was used to measure the type and degree of change brought about by the two disasters. The original scale was modified by replacing “this event” in all statements with either “2021 BC wildfire” or “2021 Western Germany flood”. The material change subscale included 6 items, whereas the other 6 items were included in the psychological change subscale. For each statement, respondents rated their agreement on a 1 (strongly disagree)-to-5 (strongly agree) Likert scale. The overall material impact of each disaster was calculated by averaging the ratings of the 6 material items, and the overall psychological impact of each disaster was calculated by averaging the ratings of the 6 psychological items.

For the current samples, the internal consistency coefficient for the BC-fire sample was 0.87 (Cronbach’s αmaterial = 0.89; Cronbach’s αpsychological = 0.87). For the Germany-flood sample, the internal consistency coefficient was 0.82 (Cronbach’s αmaterial = 0.74; Cronbach’s αpsychological = 0.85).

3.2. Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale

This 21-item scale assesses the negative emotional state, that is, depression, anxiety, and stress (Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995, Supplementary File S2). Each of the three subscales (depression, anxiety, stress) comprised 7 items. For each item, participants rated on a 0 (did not apply to me at all)-to-3 (applied to me very much or most of the time) Likert scale. A total score for each subscale was calculated by summing the ratings of its respective 7 items. According to the scoring guidelines, the cut-off scores for normal, mild, and moderate depression are 0–4, 5–6, and 7–10, respectively. For anxiety, the cut-offs are 0–3, 4–5, and 6–7, representing normal, mild, and moderate; and for stress, they are 0–7, 8–9, and 10–12, defining normal, mild, and moderate levels individually.

For the current samples, the internal-consistency coefficient of the BC-fire sample was 0.94 (Cronbach’s αdepression = 0.90; Cronbach’s αanxiety = 0.81; Cronbach’s αstress = 0.89). For the German respondents, we used the German-validated version of the DASS-21 (Nilges & Essau, 2015). For the Germany-flood sample, the internal-consistency coefficient was 0.93 (Cronbach’s αdepression = 0.87; Cronbach’s αanxiety = 0.82; Cronbach’s αstress = 0.80).

3.3. Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Checklist

The 8-item abbreviated version of the PCL-5 (Price et al., 2016, Supplementary File S3) was used, which assesses the PTSD symptoms indicated by prolonged distress of individuals after experiencing a traumatic event. Participants rated their agreement with each item on a 0 (not at all)-to-4 (extremely) Likert scale, and the total score of the scale ranged between 0 and 32. The cut-off score for PTSD symptom diagnosis is 19 on this scale. For the current samples, the internal consistency coefficient (Cronbach’s α) was 0.95 for the BC-fire sample, and for the Germany-flood sample, it was 0.90.

3.4. Demographics and Disaster Consequences Questionnaire

Additionally, we collected demographic data (e.g., gender, age, education, and residential location) to capture sample characteristics and asked a few disaster-related binary questions to understand the consequences of a candidate disaster. For instance, we asked the BC and Germany groups to specify whether they were evacuated and lost their jobs and residences because of the fire or flood, respectively (i.e., Yes/No response). Also, we provided a couple of rating items to indicate the damage level of their pre-disaster (fire or flood) residence and property other than their house on a scale of 0 (no damage) to 4 (complete destruction).

Furthermore, in two separate questions, participants were asked to rate how abandoned they felt by their social circle or community (i.e., “How much did you feel left alone/abandoned by your friends and acquaintances or your neighbors and community during or after the [disaster] of [region] in 2021?”) and their government (i.e., “How much did you feel left alone/abandoned by the government officials/state during or after the [disaster] of [region] in 2021?”) on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (not left alone/abandoned) to 4 (completely left alone/abandoned).

Finally, at the end of each survey, an open-ended question was provided to respondents to describe their experience with the particular disaster (i.e., 2021 BC fire/2021 Western Germany flood). We mention this for thoroughness, but these open-ended responses are not explored further in this article.

4. Procedure

A convenience/snowball sampling strategy was used to recruit participants. This strategy was implemented during the initial phase of data collection, involving advertising on social media and through academic channels, including institutional email lists and websites. The recruitment advertisement provided a URL directing participants to the online survey questionnaire. For the BC-fire respondents, an English version of the survey form was disseminated. As for the Germany-flood participants, a German-translated version of the survey was distributed. Respondents had the flexibility to complete the survey form at their own pace. In the initial survey, participants indicated their willingness to participate in a follow-up. Hence, for the second survey, these respondents received an invitation email containing the link to the online questionnaire and were requested to fill out the Google form at their convenience. For both waves, participation was entirely voluntary, and respondents were not compensated in any way. Only people whose age was 18 years or older and who were residents of either BC, Canada, or Western Germany were eligible to participate. Participants who did not meet these criteria were excluded from the study. Only fully completed survey forms were considered for analysis. Informed consent was acquired from all subjects involved in the study.

5. Results

The statistical software program SPSS v.26 (IBM SPSS, Statistics, New York, NY, USA) was used to perform data analysis. Descriptive statistics, paired t-tests, repeated analysis of variance (ANOVA), and hierarchical regressions were computed.

Table 2 reports the mean material and psychological TIS ratings, DASS scores, and disaster-related ratings for each sample across the two waves.

Table 2.

Average ratings on TIS subscales, DASS, residence and property damage, and abandoned feelings (community and government) produced by respondents from British Columbia and Western Germany.

5.1. Mean Comparison Between Wave 1 and Wave 2 Responses

Paired t-tests (see Table 2) were conducted to statistically compare the average ratings between the two waves in each sample. This data makes a few points.

5.1.1. Transitional Impact Scale

First, the 2021 fire did not produce major changes in the routine lives of BC respondents over time, indicating a mean material TIS of 2.59 (p > 0.05). However, at the outset, the fire produced a moderate change in the psychological state of the BC respondents (mean psychological TIS 3.58), and then, a year later, the average score dropped reliably low to 3.23 (p < 0.05).

Also, immediately after, the 2021 flood produced a moderate change in the fabric of daily lives of the Germans (mean material TIS 3.24), but after a year, the mean rating significantly decreased to a midpoint of 3.00 (p < 0.05). In contrast, at the early stage, the flood of 2021 produced a notable change in the psychological condition of the German respondents (mean psychological TIS 4.15). After a year, although the average psychological-TIS score was reliably lower than the first wave (p < 0.05), the mean rating was still quite high (3.79).

In comparison, Shi and Brown (2016) found immigration from China to Canada had a profound impact, considering both material and psychological mean TIS scores were higher than 4.0. Therefore, it could be said that, overall, the fire and flood of 2021 did not produce major, enduring changes in the fabric of daily lives of the respondents in BC and Western Germany. However, during the onset, both the BC-fire and Germany-flood people experienced more psychological change than at a later period. Notably, the 2021 flood brought major changes in the psychological state of the Germans.

5.1.2. Depression, Anxiety, Stress, and PTSD Scale

Immediately after the 2021 fire, the BC people felt significantly more depressed, anxious, and stressed than they felt a year after the fire (all p < 0.05). However, over time, they did not experience strong PTSD-like symptoms (all p > 0.05).

Also, both at the outset and at the later period of the 2021 flood, the German respondents had moderate levels of depression and stress and severe levels of anxiety (all p > 0.05). Importantly, the Germany-flood group reported not experiencing PTSD-like symptoms over time (all p > 0.05).

These results indicate that, for the most part, respondents of BC and Germany who underwent the fire and flood experienced long-term negative consequences to their sense of well-being.

5.1.3. Feeling-of-Abandonment Ratings

At the onset of the 2021 fire, BC respondents reported feeling more abandoned by their government and agencies than they felt one year after the fire (p < 0.05). Also, over time, these respondents expressed that they experienced minimal to no feelings of abandonment by their community (p > 0.05).

Moreover, both at the early and later stages of the 2021 flood, the Germans reported feeling a little abandoned by their community (p > 0.05) but indicated strong feelings of abandonment by their government and agencies (p > 0.05).

Hence, it could be said that individuals affected by fire or flood may have a more positive view of their respective communities than of their respective officials in terms of disaster response.

5.1.4. Residence and Property-Damage Ratings

Over time, the Germany-flood group reported having experienced some damage to their pre-flood residence and property (all p > 0.05). The BC-fire group also reported having little to no damage to their pre-fire residence and property in the long run (all p > 0.05). That being said, overall, the fire and flood of 2021 somewhat affected the material circumstances of these BC and German respondents, respectively, but these effects were not catastrophic.

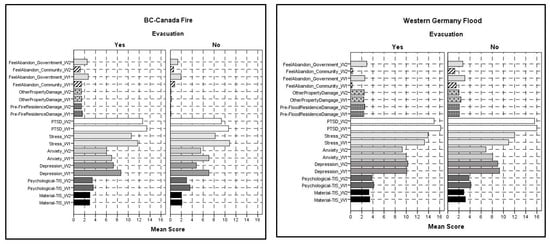

5.2. Role of Evacuation

Also, given that many respondents were evacuated during the 2021 BC fire (58.3%) and Germany flood (26.8%), the mean scores of the rating items were displayed as a function of evacuation between Wave 1 and Wave 2 for the BC-Fire and Germany-flood sample, respectively (Figure 2). To explore further, we conducted a separate repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) for the BC-fire and Germany-flood groups, with evacuation as a between-subjects factor and wave (i.e., Wave 1 rating items vs. Wave 2 rating items) as a within-subjects factor.

Figure 2.

Average response of the rating items provided by participants from British Columbia and Western Germany of evacuees and non-evacuees across two waves.

5.2.1. BC Fire of 2021

For the BC-fire group, the analysis of the material-TIS ratings produced a significant main effect of evacuation, F (1, 46) = 7.92, p < 0.01, partial η2 = 0.147, but no reliable main effect of wave (p > 0.05, partial η2 = 0.000) and no significant effect of wave x evacuation interaction (p > 0.05, partial η2 = 0.003). Post hoc pairwise comparisons with a Bonferroni correction indicated that in both waves, evacuees provided a higher material-TIS rating than the non-evacuees (p < 0.01). The repeated ANOVA of psychological-TIS responses produced a significant main effect of wave, F (1, 46) = 5.39, p < 0.05, partial η2 = 0.105, but not of evacuation (p > 0.05, partial η2 = 0.013). The wave x evacuation interaction was also non-significant, p > 0.05, partial η2 = 0.039. Post hoc pairwise comparisons with a Bonferroni correction indicated that both evacuees and non-evacuees rated the psychological TIS higher at the outset of the fire than in the later period (p < 0.05).

Again, when performing repeated ANOVA of the depression, anxiety, stress, and PTSD ratings separately, we found a reliable main effect of wave for depression, F (1, 46) = 8.92, p < 0.01, partial η2 = 0.162; anxiety, F (1, 46) = 6.69, p < 0.05, partial η2 = 0.127; and stress, F (1, 46) = 6.76, p < 0.05, partial η2 = 0.128, but no reliable effect for PTSD (p > 0.05, partial η2 = 0.036). Also, no significant main effect of evacuation was observed for depression (partial η2 = 0.035), anxiety (partial η2 = 0.000), stress (partial η2 = 0.020), or PTSD (partial η2 = 0.028), all p > 0.05. Moreover, the wave x evacuation interaction was non-reliable for depression (partial η2 = 0.013), anxiety (partial η2 = 0.008), stress (partial η2 = 0.023), and PTSD (partial η2 = 0.003), all p > 0.05. Post hoc pairwise comparisons with a Bonferroni correction indicated that both evacuees and non-evacuees reported having felt more depressed (p < 0.01), anxious, and stressed (both p < 0.05) soon after the fire than a year later.

Next, a repeated ANOVA analysis was conducted separately on the damage ratings of pre-fire residences and property, which yielded a significant main effect of evacuation for residence damage, F (1, 46) = 15.65, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.254, and property damage, F (1, 46) = 13.52, p < 0.01, partial η2 = 0.227. Post hoc pairwise comparisons with a Bonferroni correction indicated that in both waves, the evacuated group reported having experienced more damage to their residence (p < 0.001) and property (p < 0.01) than the non-evacuated group. In contrast, the main effect of wave was non-reliable for residence damage (partial η2 = 0.039) and property damage (partial η2 = 0.007), all p > 0.05. Also, the wave x evacuation interaction was non-significant for property damage (partial η2 = 0.002) and residence damage (partial η2 = 0.013), all p > 0.05. This finding indicates that the people who had to leave their living place because of the fire also experienced more destruction to their houses, belongings, and properties compared to those who did not have to leave.

Finally, when conducting a repeated ANOVA of the ratings about feelings of abandonment (community vs. government), we found a significant main effect of wave, F (3, 138) = 18.27, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.284 and evacuation, F (1, 46) = 5.98, p < 0.05, partial η2 = 0.115, but no significant effect of wave x evacuation interaction (p > 0.05, partial η2 = 0.012). Post hoc pairwise comparisons with a Bonferroni correction indicated that, in both waves, the feeling of abandonment was higher among evacuees than non-evacuees (p < 0.05). Particularly, the evacuees felt more abandoned by their government than their community, and this feeling of abandonment was highest right after the fire, all p < 0.001.

5.2.2. Western Germany Flood of 2021

For the Germany-flood group, the analysis of material-TIS ratings yielded a significant main effect of wave, F (1, 39) = 4.32, p < 0.05, partial η2 = 0.100, but no reliable main effect of evacuation (p > 0.05, partial η2 = 0.025) and no significant effect of wave x evacuation interaction (p > 0.05, partial η2 = 0.009). Post hoc pairwise comparisons with a Bonferroni correction indicated that both evacuees and non-evacuees indicated a higher material-TIS rating right after the flood than a year later (p < 0.05). The repeated ANOVA of psychological-TIS responses produced a significant main effect of wave, F (1, 39) = 5.36, p < 0.05, partial η2 = 0.121, but no reliable main effect of evacuation (p > 0.05, partial η2 = 0.000). The wave x evacuation interaction was also non-significant, p > 0.05, partial η2 = 0.000. Post hoc pairwise comparisons with a Bonferroni correction indicated that both evacuees and non-evacuees rated the psychological TIS higher soon after the flood than in the later period (p < 0.05).

Moreover, when performing separate repeated ANOVA of the depression, anxiety, stress, and PTSD ratings, we found no reliable main effect of wave for depression (partial η2 = 0.000), anxiety (partial η2 = 0.031), stress (partial η2 = 0.022), or PTSD (partial η2 = 0.013), all p > 0.05. Furthermore, no significant main effect of evacuation was observed for depression (partial η2 = 0.008), anxiety (partial η2 = 0.037), stress (partial η2 = 0.039), or PTSD (partial η2 = 0.000), all p > 0.05. Also, the wave x evacuation interaction was non-reliable for depression (partial η2 = 0.002), anxiety (partial η2 = 0.002), stress (partial η2 = 0.001), and PTSD (partial η2 = 0.003), all p > 0.05.

Again, a repeated ANOVA analysis was conducted separately on the damage ratings of pre-flood residence and property, which produced non-significant main effects of wave for residence damage (partial η2 = 0.022) and property damage (partial η2 = 0.008), all p > 0.05. The main effect of evacuation was also non-reliable for residence damage (partial η2 = 0.018) and property damage (partial η2 = 0.006), all p > 0.05. Moreover, the wave x evacuation interaction was non-significant for property damage (partial η2 = 0.023) and residence damage (partial η2 = 0.022), all p > 0.05. This finding suggests that, evacuated or not, overall, the flood might have caused some damage to all the houses and properties of those who were living in the affected area.

Finally, when conducting a repeated ANOVA of the ratings about feelings of abandonment (community vs. government), we found a significant main effect of wave, F (3, 117) = 35.87, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.479, and evacuation, F (1, 39) = 4.41, p < 0.05, partial η2 = 0.102, but no significant effect of wave x evacuation interaction (p > 0.05, partial η2 = 0.064). Post hoc pairwise comparisons with a Bonferroni correction indicated that, in both waves, interestingly, the feeling of abandonment was higher among non-evacuees than evacuees (p < 0.05). To elaborate, the non-evacuees felt more abandoned by their government than their community, and this feeling was greatest immediately after the flood, all p < 0.001.

5.3. Predictors of DASS and PTSD

As we were interested in gaining insight into the long-term association between disaster-induced material and psychological change (transition) and mental-health issues, we performed a set of regressions for Wave 1 and Wave 2. Particularly, for each of the three DASS variables and PTSD, we fitted a multiple linear regression, using location—disaster (BC fire or Germany flood), material TIS, psychological TIS, feeling of abandonment—community, and feeling of abandonment—government as predictors. These variables were entered hierarchically, with location-disaster entered first as a control variable. We included the location—disaster as a control variable to ensure the robustness of our findings. The output of these analyses is presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Hierarchical regression results for DASS and PTSD.

It is noteworthy that, in this context, the non-significance of the location—disaster variable implies that the specific disaster location (flood in Germany or wildfire in BC) did not influence the relationship among material change, psychological change, and mental-health consequence. Moreover, these regressions suggest that, over time, the levels of depression, anxiety, stress, and PTSD were reliably associated with psychological change but not with material change. Also, during the first wave, depression, stress, and PTSD were associated with feeling abandoned by the community, but not with feelings of abandonment by the government. Moreover, only PTSD was associated with feeling abandoned by both the community and government during the second wave.

6. Discussion

This study examined the long-term transitional impact and mental-health consequences for individuals who experienced a major fire in British Columbia, Canada, or a major flood in Western Germany. As expected, immediately after the flood, the Germans experienced moderate to high levels of material and psychological change. However, over time, the flood did not appear to produce a profound alteration in most of the respondents’ lives. As for the fire, in general, the BC people experienced higher psychological changes during Wave 1 than Wave 2, but their material change remained moderately stable in the aftermath. That being said, over time, the fire likely did not produce a major alteration in the lives of most participants.

Also, as we anticipated, the BC respondents experienced high levels of depression, anxiety, and stress soon after the fire, but that improved somewhat over time. This could be explained by the fact that experiencing the wildfire is likely to have evoked increased feelings of distress as a typical psychological response to the onset of extreme weather events (Bratu et al., 2022). In contrast, German respondents experienced moderate to severe levels of depression, anxiety, and stress across the two waves of data collection. This is likely because, although Germans were aware of the risk and impact of the flood, they were not prepared for the post-flood severity (Zander et al., 2023). Notably, neither group experienced high levels of PTSD symptoms. Furthermore, soon after the fire, BC respondents felt more abandoned by their government than they felt a year after the fire. Also, with time, these respondents indicated that they experienced minimal to no feelings of abandonment by their community. Moreover, immediately after the outset and later stages of the flood, the Germans felt little abandoned by their community, but expressed heightened feelings of abandonment by their government.

When conditioned on the evacuation, unsurprisingly, the evacuees of the BC fire reported more material change than the non-evacuees. This indicates that those who were evacuated likely endured marked alterations in their lives compared to those who were not evacuated. This makes sense, as those who were displaced from home might have experienced a larger change in their life elements in terms of activities they used to do, people they used to meet, places they used to go, etc., at least temporarily. Also, both evacuated and non-evacuated groups reported experiencing higher levels of psychological change immediately after the fire than they did a year later. This suggests that the fire likely affected the beliefs, attitudes, feelings, and worldview of all the respondents residing in the affected area, especially during the onset. That being said, the experience of the fire disaster itself appears to have been distressing, and this may well have affected people’s psychological conditions, irrespective of its material consequences. Moreover, soon after the fire, our data indicates that everyone, regardless of being displaced or not, was emotionally distraught, which may have led to the development of mental-health-related problems. Additionally, over time, fire-related PTSD symptoms were not directly linked to whether or not an individual had to evacuate. Furthermore, those who faced displacement due to the fire reported being more upset with governmental measures implemented to tackle the wildfire consequences than those who did not.

As for the German flood, surprisingly, whether the flood caused displacement or not, all individuals initially indicated having experienced significant changes in their daily lives. Moreover, Germans reported having experienced more psychological changes at the early stage of the flood than the Canadians experienced soon after the wildfire. That being said, at least during Wave 1, the flood appears to have affected the beliefs, attitudes, sense of self, and morality of all the respondents. The reason might be that the flood itself was stress-evoking, and this affected people’s psychological states regardless of the extent of its physical impact. Furthermore, for the duration of the flood, it seems that all respondents, evacuated or not, were to some degree depressed, anxious, and stressed, and as such, displayed distress-like symptoms. Also, interestingly, non-evacuee Germans were more upset with their government than the evacuees. One possibility could be that the former felt they were overlooked by the government, whereas the latter received direct aid through official channels.

Moreover, whether subjected to fire or flood, only psychological change was reliably associated with depression, anxiety, stress, and PTSD levels at Wave 1 and at Wave 2. Here, it is important to note that, neither disaster produced enduring changes in housing or employment for most people in the affected regions. Also, feeling abandoned by the community was solely associated with depression, stress, and PTSD at the early stage. However, at the later stage, both feeling abandoned by the community and government were reliably associated with PTSD only.

These findings reveal several important points. First, it is evident from the TIS data that, overall, both the flood and the fire generated a moderate change in the respondents’ material conditions. In other words, during the first wave and the second, the 2021 flood and fire appeared not to have brought cataclysmic changes to the lives of most of the affected people. Previous studies have shown that significant transitional events, which have a substantial impact on one’s life, resulted in material TIS scores of 4.0 or higher (Shi & Brown, 2016; Gu et al., 2017). Indeed, neither disaster produced enduring changes in housing or employment for most people in the affected regions. For instance, both evacuees and non-evacuees of the German flood reported little damage to their properties and residences (i.e., average ratings around 2.0). Evacuees of the BC fire did report more damage to their residences and property than the non-evacuees, but the level of damage was still quite limited (i.e., average ratings between 0.1 and 1.5). This pattern of results suggests that the fabric of daily lives did change for many flood- or fire-affected individuals, but the change was not radical (Nourkova & Brown, 2015; Heanoy et al., 2023).

Interestingly, overall, the German respondents reported greater psychological change over time. Perhaps one explanation for this is that the 2021 flood was unforeseen and overwhelming, such that it was beyond the imagination and understanding of the people (Nerlich & Jaspal, 2023). To elaborate, this unprecedented flood claimed nearly 200 lives and caused havoc to buildings and infrastructure facilities such as bridges, roads, rail tracks, and the power supply (Cornwall, 2021; Thieken et al., 2023). Therefore, historically, although these people are used to floods, they had never experienced a flood like this, and this made the 2021 flood difficult for people in the region to respond to and comprehend (Kühne et al., 2021; Nerlich & Jaspal, 2023). As a result, for both evacuees and non-evacuees, the flood evoked a sense of helplessness and insecurity, which in turn may have affected their beliefs, emotions, and worldview (Fekete & Sandholz, 2021). In contrast, as a result of their frequent experience with wildfires, communities in BC have undertaken a proactive wildfire management approach with the active support of federal and provincial agencies (Copes-Gerbitz et al., 2022; Crowley et al., 2022). The idea of shared responsibility, combined in some cases with personal experience, is likely to have cushioned the BC respondents, whether evacuated or not, against experiencing extremely negative thoughts and feelings in response to the wildfire (Devisscher et al., 2021). Nonetheless, at the onset, BC respondents experienced elevated psychological change as the 2021 wildfire was notably destructive (Parisien et al., 2023; Hoffman et al., 2022).

Second, we did find a relatively strong link between the mental-health measures and the degree of psychological change caused by fire or flood disasters. One way to explain this is to concede that, in 2021, the wildfire in BC and the flood in Western Germany resulted in profound and prolonged disruption to their lives (e.g., commutes to work, grocery shopping), which in turn might have caused people to worry about their ability to return to their pre-disaster living situations (Moghadas et al., 2023; Thieken et al., 2023; Copes-Gerbitz et al., 2022; Hertelendy et al., 2022). Thus, evacuee or not, this type of uncertainty may have produced enough emotional strain to make these individuals suffer from depression and anxiety (Afifi et al., 2012; Mao & Agyapong, 2021; Saeed & Gargano, 2022). This is consistent with prior research demonstrating an increased prevalence of negative mental-health sequelae following a disaster, regardless of the disaster type (Beaglehole et al., 2018; J. Y. Lee et al., 2020; Leppold et al., 2022; Heanoy & Brown, 2024).

Third, both the BC-fire and Germany-flood groups felt more abandoned by their respective governments than by their respective communities. We speculate that this reflects people’s disaffection with the speed and nature of post-disaster support provided (or not provided) by nominally responsible government agencies (Morganstein & Ursano, 2020; Townshend et al., 2015; Mao & Agyapong, 2021; Fothergill & Peek, 2004). In other words, disaster-experienced individuals may have clear expectations of their government and officials, and when the government fails to meet the expectations, the affected individuals are disappointed and frustrated (Jong & Dückers, 2018; Albrecht, 2017). Consistent with this position, we found that BC-fire respondents who were evacuated felt increased levels of abandonment by their governments than those who were not evacuated. As noted earlier, non-evacuees of the German flood felt more abandoned by their officials than evacuees. An explanation could be that non-evacuated individuals might have felt that evacuees were better supported. In other words, non-evacuees might have felt neglected by officials (Thompson et al., 2017). To elaborate, evacuees often receive direct government support in the form of monetary relief, shelter, and sometimes medical care. Non-evacuees might perceive this as preferential treatment for evacuees and feel excluded from recovery assistance (Aguirre, 2005; Bowser & Cutter, 2015).

In contrast, following a disaster, individuals in affected communities often bond over a shared calamitous experience. This, coupled with giving and receiving social support, boosts a sense of belonging and facilitates recovery (Gim & Shin, 2022; Quinn et al., 2020; Gibbs et al., 2013; Bakic & Ajdukovic, 2021). Consistent with this notion, both evacuees and non-evacuees of the BC fire reported that they did not feel abandoned by their communities. However, notably, the Germany-flood non-evacuees felt more abandoned by their community than the evacuees. One possible explanation could be that the non-evacuees had low levels of perceived community resilience because the social capital of their community might have been sparse (Masson et al., 2019). Therefore, they likely had to rely more on their personal resources than community-provided interpersonal resources (Wind & Komproe, 2012; Noel et al., 2018). In other words, when people perceive their community’s ability to efficiently handle disaster events, they may be buffered against negative feelings such as helplessness, even though there is a greater disaster-related impact (Wheaton, 1985; Bonanno et al., 2010; Masson et al., 2019). Furthermore, whether faced with fire or flood, the well-being of the respondents was strongly associated with their feelings towards the community.

In short, following the flood and fire of 2021, it appears that changes to people’s psychological state, rather than changes to their material circumstances, might have driven post-disaster well-being consequences. In other words, despite the disaster types, it is possible that, in the absence of enduring changes in material condition (e.g., job loss, loss of residence), people’s immediate and long-term well-being might be defined by the levels of disaster-specific psychological changes experienced over time.

Limitations

Despite the strength of adopting a longitudinal design, this study has its limitations. In particular, only 48 and 41 participants took part in both waves, so caution should be exercised when generalizing from the results. More specifically, the association between the effect of disaster-related transition and well-being consequences will need to be demonstrated in the context of larger representative samples. Furthermore, since we utilized a convenient sampling strategy, certain peers (e.g., females, college graduates) might have been oversampled. Also, although DASS-21 and PCL-5 brief are commonly used assessment tools, they are self-reported and susceptible to response bias (Stuart et al., 2014). Moreover, these self-reported measures might not be equivalent to diagnostic clinical interviews and could lead to conservative estimates (Rush et al., 1987). Nonetheless, this study is important in the sense that it contributes to the insight that, despite disaster types, affected individuals’ mental health may be greatly influenced by the degree of disaster-specific material and psychological changes they endure in the long run (Friesema et al., 1979; Wright et al., 1979; Fussell et al., 2017; Raker, 2020).

7. Conclusions

As we know, this is the first study to examine the material and psychological changes brought about by the flood and wildfire of 2021, and how these changes affected the mental health of the residents of Western Germany and BC, Canada over time. In retrospect, it is clear that these disasters produced a period of emotional turmoil in the lives of those affected. In addition, many people did experience a change in their routines (e.g., evacuation). However, these changes were not generally life-altering. Likewise, although some people experienced considerable and enduring changes in their psychological outlook, others did not. Furthermore, although many respondents reported elevated levels of mental distress, for some, the level was not extreme. In short, the German flood and the BC fire of 2021 did bring marked changes to the lives of many individuals that led to negative well-being outcomes, but for some, the consequences were not calamitous.

However, the picture might have been different had we focused specifically on more vulnerable populations (e.g., house destroyed, injury/death of loved ones). Nonetheless, it is crucial to recognize that there is often a distinction between the initial emotional response to a crisis and its long-term effects on the lives of those impacted (Newnham et al., 2022). Therefore, it is important to follow disasters over time, because some individuals gradually adapt to minor disruptions in their routine, whereas others have to deal with profound life changes, which can bring on major mental-health challenges (Sarason et al., 1978; Tennant, 2002; Uzer et al., 2020). Also, going forward, it would be useful to collect data from a single community experiencing multiple disaster types, or different communities experiencing the same disaster. Either way, this would allow us to compare the true extent of the transitional impact of disasters and their associated mental-health consequences.

In conclusion, we believe the current study contributes to the understanding of the needs and support required for affected individuals, as well as the communities they reside in, in order to facilitate post-disaster recovery. As such, this research highlights the importance of robust post-disaster mental-health support to foster community resilience. Therefore, given the lengthy recovery times, prioritizing post-disaster mental-health care is essential in the affected communities to facilitate long-term psychosocial adaptation (Hayes et al., 2020; Lalani & Drolet, 2019). Hence, evidence-based post-disaster recovery programs should be developed involving practitioners, policymakers, and stakeholders to help affected individuals return to their pre-disaster functioning.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/psycholint7020049/s1, File S1: Transitional Impact Scale (TIS-12); File S2: Depression, Anxiety, Stress Scale (DASS-21); File S3: Post-traumatic Checklist-8 item (PCL-5).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.Z.H. and N.R.B.; methodology, E.Z.H. and N.R.B.; formal analysis, E.Z.H.; data curation, E.Z.H.; project administration, E.N. and T.H.; writing—original draft preparation, E.Z.H.; writing—review and editing, E.N., T.H., and N.R.B.; visualization, E.Z.H.; supervision, N.R.B., E.N., and T.H.; funding acquisition, N.R.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by N.R.B.’s Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) Discovery Grant, RES0038944.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and was reviewed and approved by the Research Ethics Board, University of Alberta (Pro00113126, 10 August 2021, Germany-flood; Pro00115278, 08 November 2021, BC-fire) and the University of British Columbia-Okanagan (H21-03571, 20 December 2021, BC-fire).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The anonymous data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Demographic characteristics and average ratings of scales of British Columbia (n = 74) and Western Germany (n = 34) respondents of Wave 1 only.

Table A1.

Demographic characteristics and average ratings of scales of British Columbia (n = 74) and Western Germany (n = 34) respondents of Wave 1 only.

| BC-Fire | Germany-Flood | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (M, SD) | 50.32, 13.37 | 46.41, 10.68 | ||

| Gender (n, %) | ||||

| Female | 50, 67.1% | 29, 87.5% | ||

| Male | 23, 31.5% | 5, 12.5% | ||

| Other | 1, 1.4% | - | ||

| Education Level (n, %) | ||||

| Less than high-school/ middle-school leaving certificate/lower-secondary-school leaving certificate/no school leaving certificate | 2, 2.7% | 4, 12.5% | ||

| High-school diploma or equivalent | 24, 31.5% | 6, 18.8% | ||

| Associate/vocational training | 18, 24.7% | 7, 21.9% | ||

| Undergraduate/technical school certificate | 18, 24.7% | 9, 25.0% | ||

| Graduate and above (e.g., diploma, Master’s, PhD) | 12, 16.4% | 7, 21.9% | ||

| Job (n, %) | ||||

| Job loss | 5, 6.8% | 3, 9.4% | ||

| No job loss | 69, 93.2% | 30, 90.6% | ||

| Residence (n, %) | ||||

| Residence loss | 11, 15.1% | 7, 21.9% | ||

| No residence loss | 63, 84.9% | 26, 78.1% | ||

| Evacuation (n, %) | ||||

| Yes | 47, 64.4% | 5, 15.6% | ||

| No | 27, 35.6% | 28, 84.4% | ||

| Pre-disaster residence damage (M, SD) | 0.90, 1.45 | 1.59, 1.34 | ||

| Property damage (M, SD) | 1.00, 1.42 | 1.38, 1.43 | ||

| Material TIS (M, SD) | 2.49, 1.15 | 2.99, 0.94 | ||

| Psychological TIS (M, SD) | 3.53, 1.16 | 3.93, 0.74 | ||

| Depression (M, SD) | 9.77, 6.23 | 9.72, 6.51 | ||

| Anxiety (M, SD) | 7.74, 5.87 | 8.50, 5.75 | ||

| Stress (M, SD) | 12.41, 6.22 | 11.94, 5.30 | ||

| PTSD (M, SD) | 13.64, 9.05 | 15.44, 7.58 | ||

| Feeling abandoned—Community (M, SD) | 1.05, 1.27 | 1.06, 1.06 | ||

| Feeling abandoned—Govt (M, SD) | 2.38, 1.54 | 2.66, 1.21 | ||

Note. For the sake of completeness, we did investigate between-group differences (only Wave 1 participants vs. both wave participants) in each sample for ratings of TIS, DASS, PTSD, house and property damage, and feelings of abandonment by the community and government. Results of an independent t-test performed separately in the BC-fire and Germany-flood groups indicate that, for all rating items, there was no difference between respondents who participated only during the first wave and those who participated in both the first and second waves (all p > 0.05).

References

- Afifi, W. A., Felix, E. D., & Afifi, T. D. (2012). The impact of uncertainty and communal coping on mental health following natural disasters. Anxiety, Stress & Coping, 25(3), 329–347. [Google Scholar]

- Aguirre, B. E. (2005). Emergency evacuations, panic, and social psychology. Psychiatry, 68(2), 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, F. (2017). Government accountability and natural disasters: The impact of natural hazard events on political trust and satisfaction with governments in Europe. Risk, Hazards & Crisis in Public Policy, 8(4), 381–410. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, D. (2009). Enduring drought then coping with climate change: Lived experience and local resolve in rural mental health. Rural Society, 19(4), 340–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakic, H., & Ajdukovic, D. (2021). Resilience after natural disasters: The process of harnessing resources in communities differentially exposed to a flood. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 12(1), 1891733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beaglehole, B., Mulder, R. T., Frampton, C. M., Boden, J. M., Newton-Howes, G., & Bell, C. J. (2018). Psychological distress and psychiatric disorder after natural disasters: Systematic review and meta-analysis. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 213(6), 716–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, H. L., Bowen, K., & Kjellstrom, T. (2010). Climate change and mental health: A causal pathways framework. International Journal of Public Health, 55, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonanno, G. A., Brewin, C. R., Kaniasty, K. Z., & Greca, A. M. L. (2010). Weighing the costs of disaster: Consequences, risks, and resilience in individuals, families, and communities. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 11(1), 1–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonanno, G. A., & Gupta, S. (2009). Resilience after disaster. In Y. Neria, S. Galea, & F. H. Norris (Eds.), Mental health and disasters (pp. 145–160). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bowser, G. C., & Cutter, S. L. (2015). Stay or go? Examining decision making and behavior in hurricane evacuations. Environment: Science and Policy for Sustainable Development, 57(6), 28–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratu, A., Card, K. G., Closson, K., Aran, N., Marshall, C., Clayton, S., Gislason, M. K., Samji, H., Martin, G., Lem, M., Logie, C. H., Takaro, T. K., & Hogg, R. S. (2022). The 2021 Western North American heat dome increased climate change anxiety among British Columbians: Results from a natural experiment. The Journal of Climate Change and Health, 6, 100116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breslau, N. (1998). Epidemiology of trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder. In R. Yehuda (Ed.), Psychological trauma (pp. 1–29). American Psychiatric Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, N. R. (2016). Transition theory: A minimalist perspective on the organization of autobiographical memory. Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition, 5(2), 128–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, N. R., Schweickart, O., & Svob, C. (2016). The effect of collective transitions on the organization and contents of autobiographical memory: A transition theory perspective. The American Journal of Psychology, 129(3), 259–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bryant, R. A., O’Donnell, M. L., Creamer, M., McFarlane, A. C., & Silove, D. (2013). A multisite analysis of the fluctuating course of posttraumatic stress disorder. JAMA Psychiatry, 70(8), 839–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bryant, R. A., Waters, E., Gibbs, L., Gallagher, H. C., Pattison, P., Lusher, D., MacDougall, C., Harms, L., Block, K., Snowdon, E., Sinnott, V., Ireton, G., Richardson, J., & Forbes, D. (2014). Psychological outcomes following the Victorian Black Saturday bushfires. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 48(7), 634–643. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S., Bagrodia, R., Pfeffer, C. C., Meli, L., & Bonanno, G. A. (2020). Anxiety and resilience in the face of natural disasters associated with climate change: A review and methodological critique. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 76, 102297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cianconi, P., Betrò, S., & Janiri, L. (2020). The impact of climate change on mental health: A systematic descriptive review. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, S. (2021). Climate change and mental health. Current Environmental Health Reports, 8, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coogan, S. C., Aftergood, O., & Flannigan, M. D. (2022). Human-and lightning-caused wildland fire ignition clusters in British Columbia, Canada. International Journal of Wildland Fire, 31(11), 1043–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copes-Gerbitz, K., Dickson-Hoyle, S., Ravensbergen, S. L., Hagerman, S. M., Daniels, L. D., & Coutu, J. (2022). Community engagement with proactive wildfire management in British Columbia, Canada: Perceptions, preferences, and barriers to action. Frontiers in Forests and Global Change, 5, 829125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornwall, W. (2021). Europe’s deadly floods leave scientists stunned. Science, 373, 372–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowley, M. A., Stockdale, C. A., Johnston, J. M., Wulder, M. A., Liu, T., McCarty, J. L., Rieb, J. T., Cardille, J. A., & White, J. C. (2022). Towards a whole-system framework for wildfire monitoring using Earth observations. Global Change Biology, 29(6), 1423–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devisscher, T., Spies, J., & Griess, V. C. (2021). Time for change: Learning from community forests to enhance the resilience of multi-value forestry in British Columbia, Canada. Land Use Policy, 103, 105317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeYoung, S. E., & Peters, M. (2016). My community, my preparedness: The role of sense of place, community, and confidence in government in disaster readiness. International Journal of Mass Emergencies & Disasters, 34(2), 250–282. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenman, D. P., & Galway, L. P. (2022). The mental health and well-being effects of wildfire smoke: A scoping review. BMC Public Health, 22(1), 2274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A.-G., & Buchner, A. (2007). G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fekete, A., & Sandholz, S. (2021). Here comes the flood, but not failure? Lessons to learn after the heavy rain and pluvial floods in Germany 2021. Water, 13(21), 3016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fothergill, A., & Peek, L. A. (2004). Poverty and disasters in the United States: A review of recent sociological findings. Natural Hazards, 32, 89–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, M. J. (2006). Disaster mental health research: Challenges for the future. In F. H. Norris, S. Galea, M. J. Friedman, & P. J. Watson (Eds.), Methods for disaster mental health research (pp. 289–301). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Friesema, H. P., Caporaso, J., Goldstein, G., Linberry, R., & McCleary, R. (1979). Aftermath: Communities after natural disasters. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Fussell, E., Curran, S. R., Dunbar, M. D., Babb, M. A., Thompson, L., & Meijer-Irons, J. (2017). Weather-related hazards and population change: A study of hurricanes and tropical storms in the United States, 1980–2012. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 669(1), 146–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galea, S., Vlahov, D., Resnick, H., Ahern, J., Susser, E., Gold, J., Bucuvalas, M., & Kilpatrick, D. (2003). Trends of probable post-traumatic stress disorder in New York City after the September 11 terrorist attacks. American Journal of Epidemiology, 158(6), 514–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, L., Waters, E., Bryant, R. A., Pattison, P., Lusher, D., Harms, L., Richardson, J., MacDougall, C., Block, K., Snowdon, E., Gallagher, H. C., Sinnott, V., Ireton, G., & Forbes, D. (2013). Beyond bushfires: Community, resilience and recovery-a longitudinal mixed method study of the medium to long term impacts of bushfires on mental health and social connectedness. BMC Public Health, 13(1), 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gim, J., & Shin, S. (2022). Disaster vulnerability and community resilience factors affecting post-disaster wellness: A longitudinal analysis of the survey on the change of life of disaster victim. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 81, 103273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldmann, E., & Galea, S. (2014). Mental health consequences of disasters. Annual Review of Public Health, 35, 169–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, X., Tse, C.-S., & Brown, N. R. (2017). The effects of collective and personal transitions on the organization and contents of autobiographical memory in older Chinese adults. Memory & Cognition, 45, 1335–1349. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, K., Poland, B., Cole, D. C., & Agic, B. (2020). Psychosocial adaptation to climate change in High River, Alberta: Implications for policy and practice. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 111, 880–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heanoy, E. Z., & Brown, N. R. (2024). Impact of natural disasters on mental health: Evidence and implications. Healthcare, 12(18), 1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heanoy, E. Z., Shi, L., & Brown, N. R. (2021). Assessing the transitional impact and mental health consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic onset. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 607976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heanoy, E. Z., Svob, C., & Brown, N. R. (2023). Assessing the long-term transitional impact and mental health consequences of the Southern Alberta Flood of 2013. Sustainability, 15(17), 12849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hertelendy, A. J., Burkle, F. M., & Ciottone, G. R. (2022). Canadian wildfires: A plague on societies well-being, inequities and cohesion. Prehospital and Disaster Medicine, 37(4), 429–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hikichi, H., Aida, J., Tsuboya, T., Kondo, K., & Kawachi, I. (2016). Can community social cohesion prevent posttraumatic stress disorder in the aftermath of a disaster? A natural experiment from the 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami. American Journal of Epidemiology, 183(10), 902–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, K. M., Christianson, A. C., Gray, R. W., & Daniels, L. (2022). Western Canada’s new wildfire reality needs a new approach to fire management. Environmental Research Letters, 17(6), 061001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, T. H., & Rahe, R. H. (1967). The social readjustment rating scale. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 11(2), 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hrabok, M., Delorme, A., & Agyapong, V. I. (2020). Threats to mental health and well-being associated with climate change. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 76, 102295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jong, W., & Dückers, M. L. (2018). The perspective of the affected: What people confronted with disasters expect from government officials and public leaders. Risk, Hazards & Crisis in Public Policy, 10(1), 14–31. [Google Scholar]

- Kaniasty, K. (2012). Predicting social psychological well-being following trauma: The role of postdisaster social support. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 4(1), 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaniasty, K., & Norris, F. H. (1993). A test of the social support deterioration model in the context of natural disaster. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 64, 395–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaniasty, K., & Norris, F. H. (2008). Longitudinal linkages between perceived social support and posttraumatic stress symptoms: Sequential roles of social causation and social selection. Journal of Traumatic Stress: Official Publication of The International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies, 21(3), 274–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, R. C., Galea, S., Gruber, M. J., Sampson, N. A., Ursano, R. J., & Wessely, S. (2008). Trends in mental illness and suicidality after Hurricane Katrina. Molecular Psychiatry, 13(4), 374–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J. E., & Moen, P. (2002). Retirement transitions, gender, and psychological well-being: A life-course, ecological model. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 57(3), P212–P222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkegaard Thomsen, D., Talarico, J. M., & Steiner, K. L. (2021). When does a wedding mark the beginning of a new chapter in one’s life? Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 62(5), 675–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kralik, D., Visentin, K., & Van Loon, A. (2006). Transition: A literature review. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 55(3), 320–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kühne, O., Koegst, L., Zimmer, M. L., & Schäffauer, G. (2021). “... Inconceivable, unrealistic and inhumane”. Internet communication on the flood disaster in West Germany of July 2021 between conspiracy theories and moralization—A neopragmatic explorative study. Sustainability, 13(20), 11427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, A. (2021, October 4). A look back at the 2021 B.C. wildfire season. CBC News. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/bc-wildfires-2021-timeline-1.6197751 (accessed on 27 August 2024).

- Lalani, N., & Drolet, J. (2019). Impacts of the 2013 floods on families’ mental health in Alberta: Perspectives of community influencers and service providers in rural communities. Best Practices in Mental Health, 15(2), 74–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C., & Gramotnev, H. (2007). Life transitions and mental health in a national cohort of young Australian women. Developmental Psychology, 43(4), 877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. Y., Kim, S. W., & Kim, J. M. (2020). The impact of community disaster trauma: A focus on emerging research of PTSD and other mental health outcomes. Chonnam Medical Journal, 56(2), 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lehmkuhl, F., Schüttrumpf, H., Schwarzbauer, J., Brüll, C., Dietze, M., Letmathe, P., Völker, C., & Hollert, H. (2022). Assessment of the 2021 summer flood in Central Europe. Environmental Sciences Europe, 34(1), 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leppold, C., Gibbs, L., Block, K., Reifels, L., & Quinn, P. (2022). Public health implications of multiple disaster exposures. The Lancet Public Health, 7(3), e274–e286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovibond, S. H., & Lovibond, P. F. (1995). Manual for the depression anxiety and stress scales (2nd ed.). Psychology Foundation of Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, W., & Agyapong, V. I. (2021). The role of social determinants in mental health and resilience after disasters: Implications for public health policy and practice. Frontiers in Public Health, 9, 658528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masson, T., Bamberg, S., Stricker, M., & Heidenreich, A. (2019). “We can help ourselves”: Does community resilience buffer against the negative impact of flooding on mental health? Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences, 19(11), 2371–2384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFarlane, A. C. (1988). The phenomenology of posttraumatic stress disorders following a natural disaster. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 176(1), 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghadas, M., Fekete, A., Rajabifard, A., & Kötter, T. (2023). The wisdom of crowds for improved disaster resilience: A near-real-time analysis of crowdsourced social media data on the 2021 flood in Germany. GeoJournal, 88(4), 4215–4241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moosavi, S., Nwaka, B., Akinjise, I., Corbett, S. E., Chue, P., Greenshaw, A. J., Silverstone, P. H., Li, X., & Agyapong, V. I. O. (2019). Mental health effects in primary care patients 18 months after a major wildfire in Fort McMurray: Risk increased by social demographic issues, clinical antecedents, and degree of fire exposure. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 10, 683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgado, A. M. (2020). Disasters, individuals, and communities: Can positive psychology contribute to community development after disaster? Community Development, 51(1), 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morganstein, J. C., & Ursano, R. J. (2020). Ecological disasters and mental health: Causes, consequences, and interventions. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neria, Y., Nandi, A., & Galea, S. (2008). Post-traumatic stress disorder following disasters: A systematic review. Psychological Medicine, 38(4), 467–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nerlich, B., & Jaspal, R. (2023). Mud, metaphors and politics: Meaning-making during the 2021 German floods. Environmental Values, 33(3), 329–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newnham, E. A., Mergelsberg, E. L., Chen, Y., Kim, Y., Gibbs, L., Dzidic, P. L., DaSilva, M. I., Chan, E. Y., Shimomura, K., Narita, Z., Huang, Z., & Leaning, J. (2022). Long term mental health trajectories after disasters and pandemics: A multilingual systematic review of prevalence, risk and protective factors. Clinical Psychology Review, 97, 102203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nilges, P., & Essau, C. (2015). Die depressions-angst-stress-Skalen: Der DASS–ein Screeningverfahren nicht nur für Schmerzpatienten. Schmerz, 29, 649–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noel, P., Cork, C., & White, R. G. (2018). Social capital and mental health in post-disaster/conflict contexts: A systematic review. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness, 12(6), 791–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, F. H., Friedman, M. J., Watson, P. J., Byrne, C. M., Diaz, E., & Kaniasty, K. (2002). 60,000 disaster victims speak: Part I. An empirical review of the empirical literature, 1981–2001. Psychiatry, 65(3), 207–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, F. H., Tracy, M., & Galea, S. (2009). Looking for resilience: Understanding the longitudinal trajectories of responses to stress. Social Science & Medicine, 68(12), 2190–2198. [Google Scholar]

- North, C. S. (2014). Current research and recent breakthroughs on the mental health effects of disasters. Current Psychiatry Reports, 16, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nourkova, V. V., & Brown, N. R. (2015). Assessing the impact of “the collapse” on the organization and content of autobiographical memory in the former Soviet Union. Journal of Social Issues, 71, 324–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opriș, A. M., Visu-Petra, L., & Brown, N. R. (2023). Living in history and by the cultural life script: What events modulate autobiographical memory organization in a sample of older adults from Romania? Memory Studies, 16(4), 912–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parisien, M. A., Barber, Q. E., Bourbonnais, M. L., Daniels, L. D., Flannigan, M. D., Gray, R. W., Hoffman, K. M., Jain, P., Stephens, S. L., Taylor, S. W., & Whitman, E. (2023). Abrupt, climate-induced increase in wildfires in British Columbia since the mid-2000s. Communications Earth & Environment, 4(1), 309. [Google Scholar]