Abstract

Background: Phenylketonuria (PKU) is a rare metabolic disorder requiring lifelong dietary treatment. Adolescents and young adults face unique challenges in managing the condition, often compromising adherence and psychological well-being. This study aimed to explore coping strategies used by patients to manage their condition and their associations with dietary adherence, PKU-related symptoms, and quality of life (QoL) in young individuals with PKU. Methods: A cross-sectional study was conducted with 21 adolescents and young adults (13–25 years) with classical PKU, followed at the Unit of Inherited Metabolic Diseases in Padua, Italy. Participants completed questionnaires assessing dietary adherence, QoL, and coping. Biochemical data were collected from medical records. Results: Only 57.1% fully adhered to the diet; social barriers like embarrassment and school/work environments hindered adherence. Adolescents reported more irritability and concentration difficulties, while young adults reported greater fatigue. QoL was moderately impacted. Avoidance coping was more frequent in young adults and correlated with irritability and lower QoL. Transcendence-oriented coping was linked to fewer insomnia symptoms. Conclusions: Coping strategies influence symptom experience and QoL in PKU. Integrating psychological support and personalized care into routine treatment is essential to improve adherence and support patients through the transition to adulthood.

Keywords:

PKU; transition; adolescence; adulthood; adherence to treatment; quality of life; coping strategies 1. Introduction

Phenylketonuria (PKU) is a rare inherited metabolic disorder caused by a deficiency of the enzyme phenylalanine hydroxylase. This leads to the accumulation of phenylalanine (Phe), an essential amino acid found in protein-rich foods, in the blood, which, if untreated, results in neurocognitive impairment and other complications (Blau et al., 2010; van Spronsen et al., 2021). The standard treatment consists of a strict low-phenylalanine diet, supplemented with amino acid-based protein substitutes to ensure proper nutrition (Burlina et al., 2021).

Maintaining lifelong adherence to this demanding regimen poses significant challenges. Medical monitoring and regular follow-up in specialized centers are necessary, but even with support, many patients struggle to remain compliant. These difficulties are especially evident during the transition from childhood to adulthood (Burlina et al., 2021; Suddaby et al., 2020).

Adolescents and young adults with PKU face the dual burden of managing a complex chronic illness while navigating developmental milestones, such as gaining autonomy, building peer relationships, and pursuing academic or work-related goals (Suddaby et al., 2020). These pressures often interfere with dietary adherence. For instance, peer influence, time constraints, and limited food options in social settings contribute to non-compliance (Burlina et al., 2021; Cazzorla et al., 2018). Studies have shown that a large proportion of adolescents exceed recommended phenylalanine levels, with Walter et al. (2002) reporting that nearly 80% of patients aged 15–19 years were outside the target metabolic range. Similar findings have been observed in young adults, who also frequently consume unauthorized protein-rich foods (Cazzorla et al., 2018). Moreover, some studies indicated that inadequate control of Phe, mainly long-term metabolic poor control, can have a negative effect on quality of life, anxiety, and depression (Landolt et al., 2002; Clacy et al., 2014).

Indeed, beyond metabolic control, strict dietary management significantly impacts psychological well-being and quality of life. Embarrassment over special food requirements and supplement use in public, combined with a desire for normalcy, can lead to social withdrawal and emotional distress (Landolt et al., 2002; Clacy et al., 2014; Bilder et al., 2013; Teruya et al., 2020; Sharman et al., 2013; Di Ciommo et al., 2012). These issues often become more pronounced during the transition from pediatric to adult care, a period frequently associated with a decline in dietary adherence and reduced engagement with health services (McGill, 2002; Biasucci et al., 2022). Nevertheless, no studies to date have simultaneously investigated dietary habits, factors influencing treatment adherence, and psychological well-being in adolescents and young adults with PKU, limiting the possibility to explore the interrelationships among these variables.

The challenges faced by patients with phenylketonuria (PKU) necessitate the implementation of strategies to manage the difficulties associated with the disease and its treatment. These strategies are referred to as coping strategies, defined as a set of cognitive and behavioral efforts employed by individuals to handle stress and adversity.

Coping strategies have been shown to play a critical role across a range of chronic illnesses. Numerous studies have investigated their impact in conditions such as cancer (Campbell et al., 2009; Spaggiari et al., 2024), type 1 diabetes (Edgar & Skinner, 2003; Graue et al., 2004), and inflammatory bowel disease (Martino et al., 2023; Becsei et al., 2021; Compas et al., 2012), demonstrating that adaptive coping mechanisms—including problem-solving, seeking social support, and positive reframing—are associated with better emotional adjustment and functional outcomes. In contrast, maladaptive coping strategies, such as avoidance and denial, are linked to poorer psychological adjustment and reduced treatment adherence.

In the context of PKU, despite the clear need for patients to develop adaptive coping mechanisms to navigate both the diagnosis and the lifelong demands of dietary management, research on coping strategies remains scarce. A limited number of studies have examined specific aspects, such as coping in relation to pregnancy in women with PKU (Roberts et al., 2014) or the strategies used by parents managing their child’s condition (Evans et al., 2019; Awiszus & Unger, 1990; Zwiesele et al., 2015). However, there is a lack of data on how adolescents and young adults with PKU cope with the psychological and social demands of the disorder, and how these coping strategies may influence treatment adherence and quality of life.

Addressing this gap in the literature is crucial for clinicians aiming to design more tailored and effective interventions, especially for patients struggling with dietary compliance.

Therefore the main aim of the present study is to explore the coping strategies adopted by adolescents and young adults with PKU, and their associations with illness- and treatment-related factors (e.g., PKU symptoms, dietary habits) as well as with quality of life.

This study has three objectives. The first goal is to describe dietary habits, treatment adherence, PKU-related symptoms, factors influencing adherence, and coping strategies, as well as their impact on quality of life, in an Italian sample of adolescents and young adults with PKU, thereby addressing a gap in the existing literature. To date, no studies have investigated all of these aspects together in a PKU population of adolescents and young adults.

Second, the study aims to assess differences between adolescents and young adults in the use of coping strategies and perceived quality of life, in order to better understand age-related differences in psychological adaptation to PKU.

The third objective is to explore the associations between patients’ coping strategies, quality of life, and various aspects of PKU management.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Procedure

From February 2024 to September 2024, all the adolescents and young adults with PKU followed by the Reference Centre for Expanded Newborn Screening, Division of Inherited Metabolic Diseases (University Hospital of Padua, Italy) were contacted to participate in the study. The inclusion criteria for patient recruitment were the following: diagnosis at birth, diagnosis of classical PKU, age between 13 and 25 years (age range for adolescents: 13–17 years; age range for young adults: 18–25 years), and a prescribed low-phenylalanine diet. Exclusion criteria included intellectual disability that would prevent adequate responses to the questionnaires and a change of treatment center for PKU in the last year. All 26 patients meeting the inclusion criteria were contacted (response rate = 81%).

This cross sectional exploratory study was conducted at a northeastern Italian center in Padova. Eligible participants were contacted to complete a series of questionnaires during outpatient visits at the reference center. A psychologist explained the objective of the study and asked patients, and their parents in the case of minors, whether they were willing to participate. Informed consent was obtained from all PKU patients prior to the administration of the questionnaires. For participants aged 13 to 17 years, consent was required from both parents, while adult patients provided their consent personally. The questionnaires were administered in paper format during routine visits, and a psychologist was available to address any questions regarding the study. Finally, disease-related information, including phenylalanine (Phe) and tyrosine (Tyr) levels, was retrieved from the medical records of patients with prior informed consent.

The study was performed in compliance with local regulatory requirements and was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the University Hospital of Padua (n.6178/AO/25).

2.2. Questionnaires

2.2.1. Socio-Demographic and General Information

Socio-demographic and general information regarding the patients were collected through an ad hoc questionnaire designed specifically for this study. Data were gathered regarding age, gender, ethnicity, family situation, and educational or work status.

2.2.2. Biochemical Data: Phe and Tyr Levels

The measurements of the average levels of phenylalanine (Phe) and tyrosine (Tyr) were taken from the year prior to the study.

The concentrations of Phe and Tyr were assessed through two main methods. The first involved patients sending blood spots from home; the second method consisted of collecting plasma levels of Phe and Tyr through blood samples taken during visits to the hospital.

2.2.3. Adherence to Treatment

To assess adherence to treatment in adolescents and young patients with PKU, the survey used by Cazzorla and colleagues in their ATTITUDE study (Cazzorla et al., 2018) was administered. This ATTITUDE survey is structured into two sections and consists mainly of closed-ended questions with predefined response options or Likert scale items to measure the intensity or frequency of specific aspects.

The first part of the survey primarily addresses dietary habits and general information regarding adherence to treatment, such as monitoring of Phe levels, protein tolerance, and assumption of special food and supplement mixtures.

The second part examines PKU symptoms, as well as the emotional and psychological factors influencing adherence to treatment.

2.2.4. Quality of Life

The Phenylketonuria Impact and Treatment Quality of Life Questionnaire (PKU-QOL) (Regnault et al., 2015) was used to assess the patient’s quality of life. This tool was specifically developed to evaluate the impact of the disease and its treatment on the quality of life of patients.

In this study, both the adolescent and adult versions of the questionnaire were used. The adolescent version is intended for patients aged 12 to 17 years and consists of 58 items, while the adult version, which is for patients aged 18 years and older, contains 65 items. The main differences between the two versions are due to the specific experiences and challenges faced by the two age groups.

Both versions are structured into four modules: PKU symptoms, general PKU issues, administration of phenylalanine-free protein supplements, and daily dietary restrictions.

Responses are provided on a Likert scale ranging from 0 to 4, with higher scores indicating a greater negative impact on quality of life. A total score and the modules’ scores are obtained, with values ranging from 0 to 100. A score below 25 indicates little or no impact on the subject’s quality of life, scores between 25 and 50 reflect a moderate impact, scores between 50 and 75 indicate a significant impact, and scores above 75 suggest a very severe impact (Regnault et al., 2015).

2.2.5. Coping Strategies

To assess coping strategies, the Coping Orientation to Problems Experienced—New Italian Version (COPE-NVI) (Foà et al., 2015) was administered in its abbreviated 25-item version, specifically adapted for the Italian population.

This questionnaire is designed to evaluate coping styles in hospital settings related to illness, where continuous monitoring of patients’ adaptive capacities is essential to enhance the most effective strategies.

The COPE-NVI measures five main coping dimensions: problem orientation, transcendent orientation, positive attitude, social support, and avoidance strategies. Responses are provided on a 6-point Likert scale (ranging from 1 = “I usually do not do this” to 6 = “I almost always do this”). By summing the item scores corresponding to each dimension, an overall score for a specific coping strategy can be obtained.

A high score indicates frequent use of the coping strategy associated with that dimension, whereas a lower score suggests infrequent use of that strategy (Foà et al., 2015).

3. Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM® SPSS 30.0.0 software (Nie et al., 1975), employing various non-parametric tests to ensure result reliability.

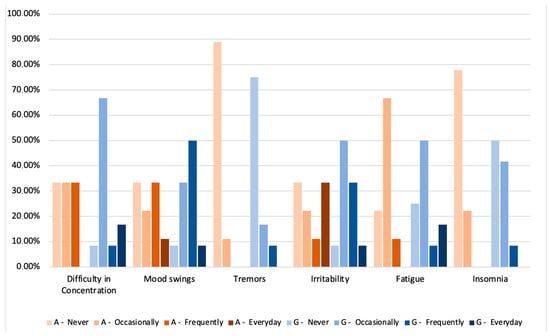

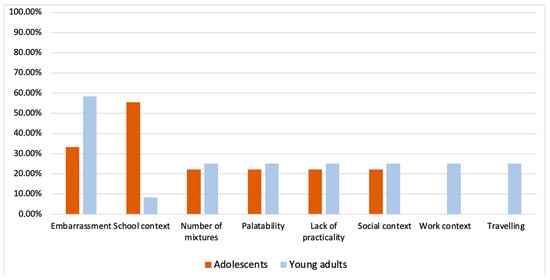

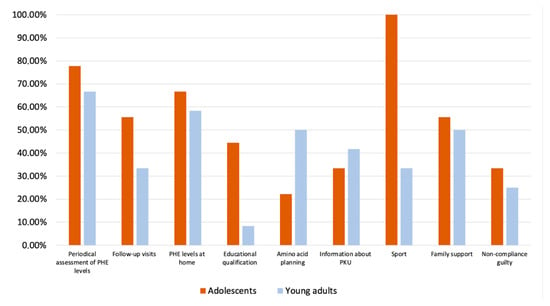

First, descriptive analyses were conducted, in line with the study by Cazzorla et al. (2018), to outline the clinical group’s profile regarding dietary habits and general information regarding adherence to treatment. Frequency charts were also generated to illustrate the distribution of key emotional and psychological factors related with treatment adherence (Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3).

Figure 1.

Frequencies (%) of the main symptoms that could be attributed to high plasma Phe levels, divided by adolescents and young adults.

Figure 2.

Frequency (%) of factors most affecting dietary adherence and consumption of amino acid mixtures, divided by adolescents and young adults.

Figure 3.

Frequency (%) of factors supporting patients in dietary adherence and consumption of amino acid mixtures, divided by adolescents and young adults.

Moreover, descriptive analyses were conducted to highlight the levels of coping strategy use and the impact of PKU on quality of life. The mean values and standard deviations of the PKU-QOL questionnaire and the COPE-NVI, divided by adolescents and young adults, are reported in Table 1. Additionally, to compare age-divided samples in terms of quality of life and coping strategies, the Mann–Whitney test was applied. This non-parametric statistical test was used to compare distributions between adolescents and young adults with PKU (Table 2).

Table 1.

Means and standard deviations (SD) of the COPE and PKU-QOL questionnaires divided by adolescents and young adults.

Table 2.

Differences between adolescents and young adults in quality of life and coping strategies.

Finally, potential correlations between quality of life, treatment adherence, and coping strategies were examined using Spearman’s correlation coefficient, another non-parametric test effective in assessing relationships between two variables. Only statistically significant correlations are reported in Table 3, Table 4 and Table 5.

Table 3.

Correlations between coping strategies, dietary habits, and PKU symptoms.

Table 4.

Correlations between dietary habits, amino acid mixture usage practices, and quality of life.

Table 5.

Correlations between coping strategies and quality of life.

For all analyses, the significance threshold was set at a p-value < 0.05.

4. Results

4.1. Sample Characteristics

A total of twenty-one patients took part in the study. The sample included twelve females (57%), eight males (38%), and one participant (5%) who decided not to specify their gender identity. Nine patients were adolescents (42.9%), and twelve patients were young adults (57.1%). The mean age of participants was 18.67 years (SD = 4.10 years). The mean Phe level of the patients was 642.1 µmol/L and the mean Tyr level was 64.2 µmol/L.

Furthermore, twelve patients (57.1%) reported being firstborn. Regarding ethnic background, the majority were of Caucasian origin (81%), while a smaller proportion were of Latin American (n = 3; 14%) and African descent (n = 1; 5%).

4.2. Dietary Habits and Adherence to Treatment

Although all patients followed a prescribed low-phenylalanine diet, only 57.1% reported adhering to it completely.

Almost the entire group (85.7%) regularly consumed all prescribed low-protein foods; nevertheless, the intake of non-permitted natural protein sources remained high, despite medical recommendations. Specifically, 65% of patients reported consuming milk and dairy products up to five times per week. In contrast, the intake of other protein sources, such as meat and fish, was generally limited for the majority of patients, with only a small proportion (14.3%) consuming these aliments one to three times per week.

Regarding the intake of amino acid mixtures, the average consumption was 3.33 servings per day. In particular, 13 patients (62%) reported taking these mixtures at breakfast, lunch, and dinner. Additionally, 33.3% of patients reported difficulties in carrying these mixtures during travel.

The median number of medical visits attended over the past two years was two.

All participants regularly monitor their phenylalanine levels through plasma or dried blood spot exams. Among them, only 52.4% reported mean Phe levels within the safe range (≤600 µmol/L), while 28.6% had mean Phe levels above the safe range (601–1000 µmol/L), and 19.0% had mean Phe levels exceeding 1000 µmol/L.

4.3. PKU Symptoms and Factors Affecting and Supporting Treatment Adherence

As shown in Figure 1, the adolescent group exhibited a prevalence of the symptom “difficulty in concentration” that is comparable to that of the young adults; however, no adolescents reported experiencing concentration problems on a daily basis.

Additionally, “mood swings” were present in both groups, with three adolescents (33.3%) and six young adults (50%) reporting experiencing this symptom frequently.

The symptoms “tremors” and “insomnia” were infrequent in both groups, with no significant differences between them.

The adolescent group reported experiencing “irritability” more frequently, with three adolescent patients (33.3%) stating that they experienced it daily. In contrast, young adults more commonly reported experiencing “fatigue,” with three (25%) stating they experienced it frequently or daily.

In Figure 2, we analyzed the factors that most influence dietary adherence and amino acid mixture intake.

The most relevant factors were the feeling of embarrassment when consuming amino acid mixtures outside the home (47.6%), and the school environment (28.6%).

Although less frequently reported (23.8%), palatability, lack of practicality, social context, and the required number of amino acid mixtures per day were also identified as factors interfering with adherence.

When analyzing differences between adolescents and young adults, a notable discrepancy emerged in the perceived embarrassment of consuming amino acid mixtures outside the home, which was higher among young adults (58.3%) compared to adolescents (33.3%). Conversely, the school environment was reported more frequently by adolescents (55.5%) than by young adults (8.3%).

Additionally, young adults identified travel (25%) and the workplace environment (25%) as interfering factors.

Regarding the factors that promote adherence to the nutritional plan (Figure 3), the most important factors reported were regular plasma Phe measurements (71.4%), engaging in physical activity (61.9%), the possibility to measure Phe at home (61.9%), family support (52.4%), and follow-up visits at the metabolic center (42.9%).

The main differences observed between the two clinical groups concerned the motivation to obtain the desired academic degree, which was higher in adolescents (44.4%), and the ability to take amino acid mixtures at specific times of the day, which was more frequently reported by young adults (50%).

All adolescents indicated participation in sports activities as a helpful factor (100%).

4.4. Coping Strategies and Impact of PKU on Quality of Life

Regarding the measurement of the quality of life levels experienced by the patients (Table 1), it was found that the majority of participants reported a moderate impact of the disease on their quality of life.

As for the more specific dimensions of the questionnaire, the distribution of perceived impact ranges from minimal to significant. The items “general PKU issues” and “PKU symptoms” are the scales where the disease has a higher impact, as highlighted by the high percentages of responses indicating moderate and significant impact.

4.5. Differences Between Adolescents and Young Adults on Quality of Life and Coping Strategies

As highlighted in Table 2, no significant differences emerged between adolescents and young adults in the PKU-QOL questionnaire, assessing quality of life.

Regarding the coping strategies, a significant difference emerged in the “Avoidance Strategies” scale, indicating that younger patients use fewer avoidance strategies compared to young adults.

4.6. Correlations

4.6.1. Coping Strategies—ATTITUDE

Several significant correlations have emerged. Specifically, avoidance strategies show a positive correlation with irritability symptoms; similarly, protein sources’ consumption is associated with social support. Conversely, a negative correlation was observed between transcendence orientation and insomnia symptoms (Table 3).

4.6.2. Attitude–QoL

Some symptoms associated with PKU (difficulty concentrating and tremors) showed a relationship with the total PKU QoL score, highlighting the connection between the disease’s impact on the individual’s daily life and specific symptoms.

Moreover, a negative correlation was found between diet adherence while traveling and the disease’s impact on quality of life (Table 4).

4.6.3. Cope–QoL

As shown in Table 5, the use of avoidance strategies positively correlates with the disease’s impact on daily life.

5. Discussion

The transition of patients with PKU from pediatric to adult care is particularly complex and vulnerable. This period coincides with significant physical and psychological changes typical of adolescence and young adulthood, along with an increasing responsibility for disease management. Key challenges include adherence to dietary therapy, navigating social situations involving food, and other condition-related difficulties (Brumm et al., 2010).

Moreover, in Italy, only a few centers provide healthcare assistance for adult PKU patients, who are still predominantly managed within pediatric settings (Biasucci et al., 2022). Consequently, the transition of PKU patients from pediatric to adult healthcare services is often difficult and challenging, further complicating the transition process and exacerbating the difficulties of adulthood with PKU.

In our study, nearly half of the patients (47.6%) had annual mean Phe levels above the safety range. This finding reflects the difficulty experienced by adolescents and young adults with PKU in achieving adequate metabolic control. Similar challenges have been reported by Walter et al. (2002), who found that up to 80% of patients aged 15–19 years exceeded the recommended phenylalanine levels. Therefore, our results appear to support previous findings in the literature.

Furthermore, only 57.1% of participants reported full adherence to dietary therapy, with a significant weekly intake of milk and dairy products and a more sporadic consumption of meat and fish, foods not permitted in the prescribed diet, observed in a large proportion of patients. Adolescents and young adults with PKU often demonstrate poor dietary adherence, characterized by reduced intake of prescribed amino acid mixtures and increased consumption of non-prescribed natural protein sources (Bilder et al., 2017). This behavior compromises metabolic control and reflects a diminished perception of disease severity and a desire for dietary normalization (Walter et al., 2002). Our findings, consistent with the existing literature, underscore the need for a better understanding of the unmet needs of individuals with PKU, thereby enabling the development of more targeted educational and psychosocial interventions to support long-term adherence.

These findings highlight the difficulties in adhering to dietary therapy in adolescents and young adults. Such challenges in adherence to dietary treatment appear to contribute to poor metabolic control, which may negatively impact both the physical and psychological well-being of these individuals (De Giorgi et al., 2023).

With regard to PKU symptomatology, both adolescents and young adults commonly reported experiencing mood swings, while adolescents reported greater irritability compared to young adults, likely due to the developmental challenges specific to this life stage, which compound the difficulties of managing therapy (Barlow & Ellard, 2006). Conversely, young adults reported experiencing more fatigue; this result is consistent with those of Cazzorla et al. (2018), who reported symptoms of fatigue, irritability, and mood swings in adult PKU patients. With regard to PKU symptomatology, both adolescents and young adults commonly reported experiencing mood swings. However, adolescents reported greater irritability and more concentration difficulties compared to young adults, likely due to the developmental challenges specific to this life stage, which may exacerbate the difficulties associated with therapy management (Barlow & Ellard, 2006). In contrast, young adults more frequently reported experiencing fatigue. This finding is consistent with those of Cazzorla et al. (2018). Similar symptoms have also been reported among adult PKU patients—although less frequently—including fatigue, irritability, and mood swings (Cazzorla et al., 2018). Moreover, a study by Al Hafid and Christodoulou (2015) identified a link between poor dietary adherence and increased symptom severity in PKU, underscoring the importance of understanding age-related differences in symptom frequency and type to inform tailored clinical management strategies across developmental stages.

Regarding factors influencing dietary compliance, social aspects emerged as key determinants in adolescents and young adults with PKU. Both of them reported that the embarrassment associated with taking amino acid mixtures outside the home was a major barrier to adherence. Additionally, school and work environments were identified as two further obstacles impacting treatment adherence. These findings are consistent with those reported by Sharman et al. (2013), who found that adolescents encountered difficulties explaining the nature of their condition and its dietary requirements to others, aspects that impact their adherence in dietary treatment.

Furthermore, approximately 20–25% of adolescent and young adult patients reported that their social environment significantly influenced their ability to follow the prescribed diet.

These findings suggest that social contexts play a crucial role in the lives of PKU patients, as they may experience embarrassment and feel different from others when required to consume specialized foods or amino acid mixtures. However, on the other hand, establishing a supportive relationship with friends and family was identified as a factor that facilitated dietary adherence. Indeed, our results also indicate that support from family and other close individuals was perceived as a key facilitator of dietary adherence in more than half of the patients.

Other significant factors influencing treatment adherence included the ability to regularly monitor Phe levels and attend routine follow-ups at the treatment center. This result seems to be consistent with the literature; indeed, Bilginsoy et al. (2005) highlighted that the waiting period for test results represented a significant barrier to adherence. Therefore, this result seems to confirm that maintaining active and consistent communication between healthcare providers and patients, particularly regarding medical aspects, is crucial. These aspects are fundamental to the process of empowering adolescents and young adults to take responsibility for their condition. Coherently with this idea, Burton et al. (2022) emphasized the importance of actively involving young patients in their care, providing positive feedback when blood Phe levels fall within the target range to enhance treatment compliance and foster greater responsibility.

Another important factor promoting therapeutic adherence in adolescents is engagement in sports activities. A possible explanation may be that structured physical activity programs encourage better overall health, promote dietary choices that align with disease management, facilitate peer interactions in a healthier social context, and require enhanced organizational and responsibility skills (Anderson & Durstine, 2019).

Regarding the impact of the disease on quality of life, most participants (71%) reported a moderate overall impact. This result aligns with findings from other studies (Bosch et al., 2015; Vieira Neto et al., 2018), indicating that adolescents and young adults with classical PKU experience a disease-related impact on their quality of life. Therefore, the existing literature on PKU seems to agree with indicating a greater impact of the disease on quality of life in adolescent and young adulthood periods; this underscores the need to have more medical attention and provide a listening space in order to support their resources and facilitate the process of self-management.

An additional aspect explored, with the aim of filling a gap in research on PKU, was the use of patients’ coping strategies. The findings revealed that a positive attitude, characterized by proactive disease acceptance and positive event reinterpretation, was the most commonly adopted strategy across both age groups. The use of coping strategies focused more on the problem has also been reported in patients with other chronic diseases, such as cancer, diabetes, recurrent abdominal pain, and chronic intestinal diseases (Campbell et al., 2009; Spaggiari et al., 2024; Martino et al., 2023; Walker et al., 2005; Jaser & White, 2011). This suggests that these findings in PKU are in line with that in other different chronic conditions; despite the challenges associated with managing a chronic illness, adolescent and young adult PKU patients demonstrate the ability to employ adaptive and positive coping strategies, which appear to support resilience development.

Nonetheless, young adults with PKU were found to use avoidance strategies more frequently than adolescents; these strategies involve attempts to escape or avoid confronting stressful situations, rather than addressing them directly. They may include minimizing the severity of the problem, denying its existence, or engaging in distracting activities to temporarily alleviate stress. Therefore, these results may suggest a greater tendency toward dysfunctional coping mechanisms in PKU adults, likely due to the increased demands of adulthood. Consistently, Arnett (2000) highlighted that young adults undergo a phase of increased autonomy and responsibility, further compounded by pressures related to career, romantic relationships, and financial independence; that may lead to a greater inclination to avoid responsibilities, thereby fostering the adoption of less adaptive coping strategies.

Moreover, our findings indicate that a higher reliance on avoidance coping strategies is associated with increased irritability symptoms and reduced quality of life. Our results on PKU align with previous studies on various chronic diseases, which have demonstrated that avoidance coping is linked to a greater presence of symptoms and lower overall well-being (Martino et al., 2023; Compas et al., 2006; Iio et al., 2024; Brink et al., 2002). It is plausible that the persistent use of this maladaptive coping strategy contributes to heightened irritability symptoms due to ineffective stress management and difficulty in addressing disease-related challenges.

Furthermore, our results showed that a higher burden of disease-related symptoms is associated with a greater impact on quality of life. This finding is consistent with the results of Olofsson et al. (2022), who demonstrated that PKU patients experiencing a higher number of disease-related symptoms report a lower perceived quality of life.

Moreover, we found that a greater use of transcendence-oriented coping strategies is linked to lower levels of insomnia. The literature suggests that spirituality plays a protective role in patients with chronic diseases, enhancing self-control and fostering trust, which positively affects quality of life (Rahmah, 2018; Niewiadomska et al., 2021). Religious coping has been identified as a significant factor in disease management across different chronic conditions, providing a framework for understanding and attributing meaning to suffering while simultaneously offering hope and improving treatment adherence (Benites et al., 2017; Bravin et al., 2019; Alvarenga et al., 2024).

Moreover, our result showed that higher non-permitted protein sources intake is associated with an increased use of social support-based coping strategy. This result extends beyond existing literature, as previous studies (Bilder et al., 2013; Cazzorla et al., 2012) have primarily emphasized the social burden of dietary adherence and its negative impact on interpersonal relationships. Our findings suggest that the ability to consume a broader range of protein sources positively influences social interactions, allowing patients to perceive social support as a resource for coping with their disease rather than as a factor compromising dietary adherence. This underscores the potential benefits of promoting dietary flexibility by involving patients in the development of personalized nutritional plans and patient-centered therapeutic approaches to enhance both psychological and social well-being.

6. Limitations

A first limitation concerns the small sample size, which could limit statistical power, and therefore compromise the reliability of the results and hinder the identification of moderate differences in statistical analyses. The decision to select only patients with the classic form of PKU reduced the possibility of achieving a larger sample size, but it was necessary to assess the impact of dietary therapy on young patients transitioning from pediatric to adult age.

Moreover, the results of this study are based on a sample of PKU patients from a center in northeastern Italy; therefore, there may be biases related to socio-cultural characteristics that could limit the generalizability of the findings. These socio-cultural factors, such as regional dietary habits, healthcare access, and family support systems, may influence patients’ experience of their conditions.

Further studies could investigate the aspects explored in our research using a longitudinal design, as our cross-sectional study presents limitations, such as the inability to establish causal relationships and to assess the progression of the disease over time. Moreover, it may be important to complement self-report questionnaires with additional assessment tools, as self-reports can be influenced by factors such as social desirability bias.

7. Conclusions

The transition from pediatric to adult care represents a critical and complex phase for PKU patients, marked by significant challenges in dietary adherence, psychological well-being, and social relationships. Our findings emphasize that metabolic control remains suboptimal in a considerable proportion of patients, with dietary non-adherence persisting into adulthood and contributing to both physical and psychological distress. Furthermore, social influences, including embarrassment for consuming amino acid mixtures and special food in social contexts and environmental barriers, play a key role in shaping adherence behaviors, underscoring the need for structured support systems that facilitate patient empowerment and self-management.

Importantly, the coping strategies adopted by adolescents and young adults appear to influence both symptomatology and quality of life, with avoidance mechanisms correlating with greater distress and reduced well-being. This highlights the necessity of integrating psychological interventions into standard care to promote adaptive coping and resilience. Additionally, fostering a multi-disciplinary approach—incorporating medical, psychological, and social support—could enhance treatment adherence and improve long-term outcomes.

Ultimately, ensuring a smoother transition to adult care requires proactive engagement from healthcare providers, family members, and broader social networks. By addressing the multi-faceted needs of PKU patients, we can mitigate the burden of the disease, enhance quality of life, and support young individuals in successfully navigating the complexities of adulthood with PKU.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.C., G.G., S.M., L.M., A.P.B., A.B.B.; methodology, C.C., G.G., S.M., L.M., V.G., R.S., A.P.B., A.B.B.; software G.G., S.M.; formal analysis, G.G., S.M.; investigation, C.C., G.G., S.M., L.M., V.G., R.S., A.P.B., A.B.B.; data curation, C.C., G.G., S.M., L.M.; writing—original draft preparation, C.C., G.G., S.M., L.M.; writing—review and editing, C.C., G.G., S.M., L.M., V.G., R.S., A.P.B., A.B.B.; visualization, C.C., G.G., S.M., L.M., V.G., R.S., A.P.B., A.B.B.; supervision, C.C., A.P.B., A.B.B.; project administration, C.C., G.G., S.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of the University-Hospital of Padua (n.6178/AO/25, approved on 23 January 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study and/or their caregivers.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Al Hafid, N., & Christodoulou, J. (2015). Phenylketonuria: A review of current and future treatments. Translational Pediatrics, 4(4), 304–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvarenga, W. A., da Cruz, I. E. C., Leite, A. C. A. B., Machado, J. R., Dos Santos, L. B. P. A., Lima, R. A. G., & Nascimento, L. C. (2024). “God gives me hope!”: Hospitalized children’s perception of the influence of religion in coping with chronic illness. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 77, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, E., & Durstine, J. L. (2019). Physical activity, exercise, and chronic diseases: A brief review. Sports Medicine and Health Science, 1(1), 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnett, J. J. (2000). Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist, 55(5), 469–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awiszus, D., & Unger, I. (1990). Coping with PKU: Results of narrative interviews with parents. European Journal of Pediatrics, 149(Suppl. S1), S45–S51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlow, J. H., & Ellard, D. R. (2006). The psychosocial well-being of children with chronic disease, their parents and siblings: An overview of the research evidence base. Child: Care, Health and Development, 32(1), 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becsei, D., Hiripi, R., Kiss, E., Szatmári, I., Arató, A., Reusz, G., Szabó, A. J., Bókay, J., & Zsidegh, P. (2021). Quality of life in children living with PKU: A single-center, cross-sectional, observational study from Hungary. Molecular Genetics and Metabolism Reports, 29, 100823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benites, A. C., Neme, C. M. B., & dos Santos, M. A. (2017). Significance of spirituality for patients with cancer receiving palliative care. Estudos de Psicologia, 34(2), 269–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biasucci, G., Brodosi, L., Bettocchi, I., Noto, D., Pochiero, F., Urban, M. L., & Burlina, A. (2022). The management of transitional care of patients affected by phenylketonuria in Italy: Review and expert opinion. Molecular Genetics and Metabolism, 136(2), 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilder, D. A., Burton, B. K., Coon, H., Leviton, L., Ashworth, J., Lundy, B. D., Vespa, H., Bakian, A. V., & Longo, N. (2013). Psychiatric symptoms in adults with phenylketonuria. Molecular Genetics and Metabolism, 108(3), 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bilder, D. A., Kobori, J. A., Cohen-Pfeffer, J. L., Johnson, E. M., Jurecki, E. R., & Grant, M. L. (2017). Neuropsychiatric comorbidities in adults with phenylketonuria: A retrospective cohort study. Molecular Genetics and Metabolism, 121(1), 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bilginsoy, C., Waitzman, N., Leonard, C. O., & Ernst, S. L. (2005). Living with phenylketonuria: Perspectives of patients and their families. Journal of Inherited Metabolic Disease, 28(5), 639–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blau, N., Van Spronsen, F. J., & Levy, H. L. (2010). Phenylketonuria. The Lancet, 376(9750), 1417–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosch, A. M., Burlina, A., Cunningham, A., Bettiol, E., Moreau-Stucker, F., Koledova, E., Benmedjahed, K., & Regnault, A. (2015). Assessment of the impact of phenylketonuria and its treatment on quality of life of patients and parents from seven European countries. Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases, 10, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bravin, A. M., Trettene, A. D. S., Andrade, L. G. M. D., & Popim, R. C. (2019). Benefits of spirituality and/or religiosity in patients with chronic kidney disease: An integrative review. Revista Brasileira de Enfermagem, 72(4), 541–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brink, E., Karlson, B. W., & Hallberg, L. M. (2002). Health experiences of first-time myocardial infarction: Factors influencing women’s and men’s health-related quality of life after five months. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 7(1), 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brumm, V. I., Bilder, D., & Waisbren, S. E. (2010). Psychiatric symptoms and disorders in phenylketonuria. Molecular Genetics and Metabolism, 99, 559–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burlina, A., Leuzzi, V., Spada, M., Carbone, M. T., Paci, S., & Tummolo, A. (2021). The management of phenylketonuria in adult patients in Italy: A survey of six specialist metabolic centers. Current Medical Research and Opinion, 37(3), 411–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, B. K., Hermida, Á., Bélanger-Quintana, A., Bell, H., Bjoraker, K. J., Christ, S. E., Grant, M. L., Harding, C. O., Huijbregts, S. C. J., Longo, N., McNutt, M. C., 2nd, Nguyen-Driver, M. D., Santos Pessoa, A. L., Rocha, J. C., Sacharow, S., Sanchez-Valle, A., Sivri, H. S., Vockley, J., Walterfang, M., … Muntau, A. C. (2022). Management of early treated adolescents and young adults with phenylketonuria: Development of international consensus recommendations using a modified Delphi approach. Molecular Genetics and Metabolism, 137(1–2), 114–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, L. K., Scaduto, M., Van Slyke, D., Niarhos, F., Whitlock, J. A., & Compas, B. E. (2009). Executive function, coping, and behavior in survivors of childhood acute lymphocytic leukemia. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 34(3), 317–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cazzorla, C., Bensi, G., Biasucci, G., Leuzzi, V., Manti, F., Musumeci, A., Papadia, F., Stoppioni, V., Tummolo, A., Vendemiale, M., Polo, G., & Burlina, A. (2018). Living with phenylketonuria in adulthood: The PKU ATTITUDE study. Molecular Genetics and Metabolism Reports, 16, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cazzorla, C., Del Rizzo, M., Burgard, P., Zanco, C., Bordugo, A., Burlina, A. B., & Burlina, A. P. (2012). Application of the WHOQOL-100 for the assessment of quality of life of adult patients with inherited metabolic diseases. Molecular Genetics and Metabolism, 106(1), 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clacy, A., Sharman, R., & McGill, J. (2014). Depression, anxiety, and stress in young adults with phenylketonuria: Associations with biochemistry. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics, 35(6), 388–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Compas, B. E., Boyer, M. C., Stanger, C., Colletti, R. B., Thomsen, A. H., Dufton, L. M., & Cole, D. A. (2006). Latent variable analysis of coping, anxiety/depression, and somatic symptoms in adolescents with chronic pain. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 74(6), 1132–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compas, B. E., Jaser, S. S., Dunn, M. J., & Rodriguez, E. M. (2012). Coping with chronic illness in childhood and adolescence. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 8(1), 455–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Giorgi, A., Nardecchia, F., Romani, C., & Leuzzi, V. (2023). Metabolic control and clinical outcome in adolescents with phenylketonuria. Molecular Genetics and Metabolism, 140(3), 107684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Ciommo, V., Forcella, E., & Cotugno, G. (2012). Living with phenylketonuria from the point of view of children, adolescents, and young adults: A qualitative study. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics, 33(3), 229–235. [Google Scholar]

- Edgar, K. A., & Skinner, T. C. (2003). Illness representations and coping as predictors of emotional well-being in adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 28(7), 485–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, S., Daly, A., Wildgoose, J., Cochrane, B., Ashmore, C., Kearney, S., & MacDonald, A. (2019). Mealtime anxiety and coping behaviour in parents and children during weaning in PKU: A case-control study. Nutrients, 11(12), 2857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foà, C., Tonarelli, A., Caricati, L., & Fruggeri, L. (2015). COPE-NVI-25: Validazione italiana della versione ridotta della Coping Orientation to the Problems Experienced (COPE-NVI). Psicologia della Salute: Quadrimestrale di Psicologia e Scienze della Salute, 2, 123–140. [Google Scholar]

- Graue, M., Wentzel-Larsen, T., Bru, E., Hanestad, B. R., & Søvik, O. (2004). The coping styles of adolescents with type 1 diabetes are associated with degree of metabolic control. Diabetes Care, 27(6), 1313–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iio, M., Nagata, M., & Narita, M. (2024). Factors associated with positive mental health in Japanese young adults with a history of chronic diseases during childhood: A qualitative study. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 76, e9–e18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaser, S. S., & White, L. E. (2011). Coping and resilience in adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Child: Care, Health and Development, 37(3), 335–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landolt, M. A., Ribi, K., Laimbacher, J., Vollrath, M., Gnehm, H. E., & Sennhauser, F. H. (2002). Posttraumatic stress disorder in parents of children with newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 27(7), 647–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martino, G., Viola, A., Vicario, C. M., Bellone, F., Silvestro, O., Squadrito, G., Schwarz, P., Lo Coco, G., Fries, W., & Catalano, A. (2023). Psychological impairment in inflammatory bowel diseases: The key role of coping and defense mechanisms. Research in Psychotherapy, 26(3), 731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- McGill, M. (2002). How do we organize smooth, effective transfer from paediatric to adult diabetes care? Hormone Research, 57(Suppl. 1), 66–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nie, N. H., Hull, C. H., Bent, D. H., & Jenkins, J. G. (1975). Statistical package for the social sciences. McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Niewiadomska, I., Jurek, K., Chwaszcz, J., Wośko, P., & Korżyńska-Piętas, M. (2021). Personal resources and spiritual change among participants’ hostilities in Ukraine: The mediating role of posttraumatic stress disorder and turn to religion. Religions, 12(3), 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olofsson, S., Gralén, K., Hoxer, C., Okhuoya, P., & Persson, U. (2022). The impact on quality of life of diet restrictions and disease symptoms associated with phenylketonuria: A time trade-off and discrete choice experiment study. The European Journal of Health Economics, 23(6), 993–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmah, H. (2018). Pengaruh dukungan sosial dan religiusitas terhadap kualitas hidup remaja penyandang disabilitas fisi. Al Qalam: Jurnal Ilmiah Keagamaan dan Kemasyarakatan, 11(23), 19–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regnault, A., Burlina, A., Cunningham, A., Bettiol, E., Moreau-Stucker, F., Benmedjahed, K., & Bosch, A. M. (2015). Development and psychometric validation of measures to assess the impact of phenylketonuria and its dietary treatment on patients’ and parents’ quality of life: The phenylketonuria–quality of life (PKU-QOL) questionnaires. Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases, 10, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, R. M., Muller, T., Sweeney, A., Bratkovic, D., & Gannoni, A. (2014). Promoting psychological well-being in women with phenylketonuria: Pregnancy-related stresses, coping strategies and supports. Molecular Genetics and Metabolism Reports, 1, 148–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sharman, R., Mulgrew, K., & Katsikitis, M. (2013). Qualitative analysis of factors affecting adherence to the phenylketonuria diet in adolescents. Clinical Nurse Specialist, 27(4), 205–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spaggiari, S., Calignano, G., Montanaro, M., Zaffani, S., Cecinati, V., Maffeis, C., & Di Riso, D. (2024). Examining coping strategies and their relation with anxiety: Implications for children diagnosed with cancer or type 1 diabetes and their caregivers. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 21(1), 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suddaby, J. S., Sohaei, D., Bell, H., Tavares, S., Lee, G. J., Szybowska, M., & So, J. (2020). Adult patient perspectives on phenylketonuria care: Highlighting the need for dedicated adult management and services. European Journal of Medical Genetics, 63(4), 103818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teruya, K. I., Remor, E., & Schwartz, I. V. D. (2020). Development of an inventory to assess perceived barriers related to PKU treatment. Journal of Patient-Reported Outcomes, 4(1), 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Spronsen, F. J., Blau, N., Harding, C., Burlina, A., Longo, N., & Bosch, A. M. (2021). Phenylketonuria. Nature reviews. Disease Primers, 7(1), 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vieira Neto, E., Maia Filho, H. D. S., Monteiro, C. B., Carvalho, L. M., Tonon, T., Vanz, A. P., Schwartz, I. V. D., & Ribeiro, M. G. (2018). Quality of life and adherence to treatment in early-treated Brazilian phenylketonuria pediatric patients. Brazilian Journal of Medical and Biological Research, 51(2), e6709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, L. S., Smith, C. A., Garber, J., & Claar, R. L. (2005). Testing a model of pain appraisal and coping in children with chronic abdominal pain. Health Psychology, 24(4), 364–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, J. H., White, F. J., Hall, S. K., MacDonald, A., Rylance, G., Boneh, A., Francis, D. E., Shortland, G. J., Schmidt, M., & Vail, A. (2002). How practical are recommendations for dietary control in phenylketonuria? Lancet, 360(9326), 55–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zwiesele, S., Bannick, A., & Trepanier, A. (2015). Parental strategies to help children with phenylketonuria (PKU) cope with feeling different. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A, 167(8), 1787–1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).