Abstract

“Sharenting” appears to have become a common practice among families, who tend to normalise the posting of children’s content on social media, which can raise concerns about the privacy, safety, and mental health of exposed children. This study examines the perceptions and practices of sharenting among families in Asunción (Paraguay). A survey of 73 parents analysed posting habits, knowledge of risks, and possible influencing factors on parental digital behaviour. Data analysis techniques such as descriptive statistics and correlation analysis were used to examine the associations between the key variables. The results reveal that 72.60% of respondents publish content about their children on social networks, while 95.89% recognise that they are concerned about the risks associated with this practice. In addition, 58.90% of the participants indicated that they were unaware of the term sharenting. The analysis suggests that there is no significant association between knowing one’s social media contacts and the decision to post information about one’s children, indicating that perceived privacy may not directly influence the practice of sharenting. This highlights the need to educate families and promote awareness of the risks of children’s exposure to digital platforms.

1. Introduction

The term sharenting, a combination of the words share and parenting (Çimke et al., 2018), refers to the practice by parents or even grandparents -known as grandsharenting- of posting photographs, videos, or any kind of information about their children (or grandchildren) on digital platforms (Staes et al., 2023). This dangerous practice has become increasingly relevant today due to growing digitisation, as technologies have transformed the way people relate and communicate with the world (Shah et al., 2019; Pedrouzo & Krynski, 2023). In recent years, especially since the COVID-19 pandemic, digital platforms have played a key role in social interaction, information dissemination and even the workplace (Litchfield et al., 2021; Venegas-Vera et al., 2020). These tools have allowed people to stay connected during confinement, leading to an increased need to share information, photos, and videos (Koh et al., 2024; Rajamohan et al., 2019). In this sense, social networks have eliminated barriers of space and time, facilitating the possibility of sharing experiences with anyone, anywhere in the world (Ho & Dayan, 2020; Hoffner & Bond, 2022; Pedrouzo & Krynski, 2023). It is from this practice of posting personal information on social networks that terms such as sharenting appear, which has been studied from various ethical and legal perspectives, as well as the risks associated with online exposure (Shah et al., 2019; Pedrouzo & Krynski, 2023).

Initially, sharenting has been perceived as a practice that allows children to grow up in the family, and is even perceived as a behaviour that strengthens family ties (Kumar & Schoenebeck, 2015; Subasi et al., 2024). However, its increase in recent years has raised concerns about children’s privacy, security, and digital identity (Burn, 2022; Doğan Keskin et al., 2023). Several studies have pointed out the risks associated with this exposure to networks, including the impact on children’s mental health and the vulnerability of children to any unknown person (Ferrara et al., 2023), such as individuals with malicious behaviour (Bozzola et al., 2022). Along these lines, a relationship has been identified between sharenting and the increased risk of grooming, a problem in which adults engage in abusive behaviour, contact minors, or search for images of children on digital platforms (Melo Laclote et al., 2025). In addition, the constant exposure of minors to social networks can generate repercussions at school, favouring situations of bullying or cyberbullying (Nieto-Sobrino et al., 2023). Likewise, this exposure increases the risk of other forms of harassment, such as sexual harassment through social networks, like sexing (Longobardi et al., 2021). Along these lines, recent research, such as that of Fernández-Alfaraz et al. (2023), has shown that teachers identify the use of digital technologies as a factor that can contribute to the incidence of bullying in early childhood education (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Risks associated with sharenting in minors.

However, despite the associated risks, the popularisation of sharenting has driven a growth in social media profiles of mothers or fathers (Instamoms; Garrido et al., 2023). These profiles have established themselves as relevant accounts on digital platforms, where parents document and share aspects of their family life, even managing to position themselves as influential profiles, taking advantage of the opportunity to generate economic benefits by using their children in digital marketing, through collaboration with brands and companies, promoting products, experiences or services (Beuckels et al., 2024). This phenomenon poses a new legal, ethical, and social challenge, as, despite offering economic opportunities, it contributes to the public exposure of their children, further increasing the aforementioned risks (Colapietro & Iannuzzi, 2024). This is why, in recent years, more and more parents are claiming that, although sharenting may appear to be a harmless form of social networking (Porfírio & Jorge, 2022), it can actually violate the rights of minors and expose them to dangers on social networks such as identity theft, cyberbullying, or the misuse of images in unsafe environments (Berg et al., 2024; Walrave et al., 2023).

Against this backdrop, this research seeks to analyse the perceptions of sharenting held by families in the city of Asunción (Paraguay) in order to identify possible factors that may influence their digital behaviour and to assess the level of knowledge they have about the risks associated with this practice. The main research objective (Phase I, Figure 2) is to analyse the habits, perceptions, and concerns of parents regarding the publication of content about their children on social networks (sharenting), as well as to assess their knowledge of the associated risks and their impact on children’s digital privacy.

Figure 2.

Research methodology phases.

Nevertheless, despite the growth of this practice globally, there is a gap in the empirical literature in the Latin American context, where studies on sharenting are scarce, compared to Europe, where there are studies in countries in the South (Garrido et al., 2023; Ferrara et al., 2024; Porfírio & Jorge, 2022), the East (Bayraktar & Çelik, 2024; Sivak & Smirnov, 2019), and in Northwestern Europe (Baxter & Czarnecka, 2025). This lack highlights the need to generate updated knowledge that allows for a better understanding of the behaviour and digital responsibility of families in this region.

Likewise, it is crucial to consider the child’s perspective on their exposure to social media where studies, such as those by Berg et al. (2024), show that when minors do not wish to be publicly exposed on social media, their decisions are sometimes not taken into account (Burn, 2022). The repeated publication of content without the minor’s consent can generate family tensions, affecting the minor’s trust in the adult (Bello, 2025). Furthermore, this unwanted exposure can have consequences for the child’s self-esteem and emotional well-being (Rachman et al., 2023).

With the intention of contributing to raising awareness about the importance of protecting children’s privacy and safety in the digital environment, this research also seeks to promote strategies that can regulate legislation regarding the exposure of minors on social networks. Through a statistical analysis of survey data, the aim is to identify trends in parental behaviour, differences according to socio-demographic factors, and the level of awareness of safety in the digital environment.

2. Materials and Methods

This research was developed in five phases: (i) problem statement and definition of objectives, where the relevance of the study on sharenting and the use of social networks was explained, along with its justification and the specific objectives to be achieved; (ii) design of the survey used as a research instrument; (iii) data collection, through the application of the questionnaire; (iv) analysis and presentation of results, using descriptive statistics, group comparisons and analysis of relationships between variables to identify significant patterns and trends; and (v) elaboration of conclusions and discussion, where the results obtained were interpreted (Figure 2).

Instrument, Variables, and Participants

The research was structured in five methodological phases, with phase II corresponding to the design of the instrument (Figure 2). It was decided to create a questionnaire aimed at fathers, mothers, or legal guardians in the city of Asunción in Paraguay, to explore the relationship between certain sociodemographic variables and parental digital behaviours, particularly in relation to the phenomenon of sharenting in urban contexts. The questionnaire is composed of 5 questions, which analyse different variables. The research was structured into five methodological phases, with phase II corresponding to the design of the instrument (Figure 2). A questionnaire was created for parents or legal guardians in the city of Asunción, Paraguay, to explore the relationship between certain sociodemographic variables and parental digital behaviours, particularly concerning the phenomenon of sharenting in urban contexts. The questionnaire consisted of 10 questions, which analysed different variables. The independent variables were age, participant age, and gender (Q8–Q10). The dependent variables were related to questions about social media contacts, posts, content, likes, leisure time, harassment, concerns, and sharenting (Q1–Q7), with dichotomous responses (female and male) (Table 1). This quantitative approach allows for the identification of behavioural patterns and relationships between variables through statistical analysis, making it suitable for exploratory population studies (Conti et al., 2024).

Table 1.

Questions of the graduate’s survey.

The research was conducted in the city of Asunción, the capital of Paraguay. Participants were selected using simple random sampling, focusing on parents residing in the country’s capital. The data collection procedure began with an informational meeting with the city’s school principals, intending to formally request their collaboration in disseminating the data collection instrument among families in the school community. The schools agreed to collaborate in the study, facilitating the dissemination of the instrument to parents interested in participating, resulting in a final sample of 73 participating parents.

A probability sample was drawn from the population of parents in Paraguay, aged 18 to over 50. Members of the target population interested in participating in the research were sent the questionnaire, which was used as the research instrument, and were asked to participate after being informed about the research objectives and data protection requirements. Participation in the sample was voluntary, free of charge, and anonymous.

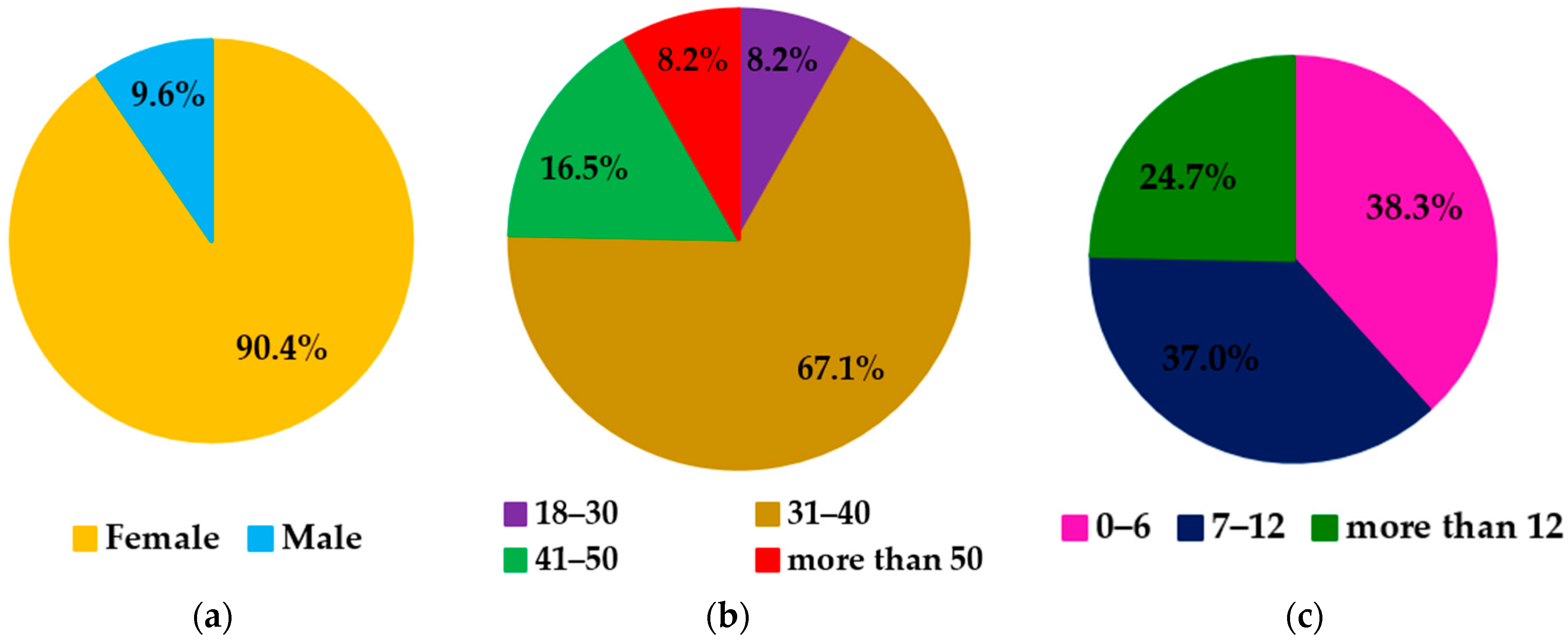

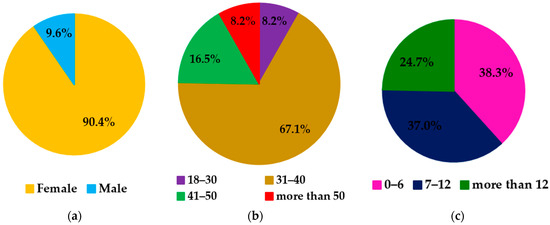

The sample participating in the study was distributed by gender as 9.6% male and 90.4% female (Figure 3a). Regarding the age of the participants, 8.2% were between 18 and 30 years old, while the majority, 67.1%, were between 31 and 40 years old. Additionally, 16.5% were between 41 and 50 years old, and 8.2% were over 50 years old (Figure 3b). Regarding the age of the children, 38.3% were less than 6 years old, 37.0% were in the range of 7 to 12 years old, and 24.7% were older than 12 years old (Figure 3c).

Figure 3.

Participants by: (a) gender; (b) age; and (c) age of children.

The instrument used was a structured questionnaire, specifically designed for this study, and composed of dichotomous responses. Its content was validated by a team of experts in bullying, educational psychology, and digital technology, ensuring its reliability and validity. It should be noted that this research was approved by the Bioethics Committee and therefore complies with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and the current regulations on personal data protection (Cantín, 2014). This ethical validation also supports the importance of the study and the scientific relevance of the research, and the instrument used. Finally, the collected data were processed and analysed using the statistical analysis software, SPSS version 29, and Microsoft Excel.

3. Results

The data obtained from the research allow us to identify key trends in the use of social networks and the perception of their risks among participants, and compare them with previous studies on the sharenting phenomenon. Firstly, 50.68% of respondents claim to know all the contacts they have added to their social networks (Q1), while 49.32% indicate that they do not know all the people on their contact list. This data reveals a significant exposure of the family to potential strangers, which is relevant, considering that social networks are a common channel for the dissemination of child content (Ferrara et al., 2024).

Regarding the publication of content related to their children (Q2), 72.60% of participants admit to sharing images, videos, audios or texts about their children on social networks, while 27.40% avoid doing so, confirming that sharenting is highly normalised among parents (Bayraktar & Çelik, 2024). However, when analysing the impact of these publications on social interaction (Q3), only 27.39% of participants indicate that they receive more ‘likes’ when they post photos with their children, in contrast to 72.60% who indicate that there is no significant increase in the number of reactions. On the other hand, 69.86% of respondents enjoy consuming content posted by other parents about their children on social media (Q4), suggesting a cultural acceptance of sharenting as a form of digital interaction (Baxter & Czarnecka, 2025); however, 30.14% do not find such posts attractive. Despite this apparent acceptance of sharenting, only 6.85% of the sample have suffered bullying or harassment because of content posted by themselves or third parties, while the vast majority, 93.15%, have not had any negative experiences of this kind (Q5). Furthermore, 95.89% of respondents express concern about the risks associated with the use of social networks (Q6), while only 4.11% consider that these risks are not a problem, suggesting a dissonance between the awareness of danger and the habitual practice of posting content on social networks (Orhan Kiliç et al., 2024a; Peimanpak et al., 2023). This contradiction has been observed in studies such as Baxter and Czarnecka (2025), where it is noted that parents tend to minimise risks if they have not experienced direct negative consequences.

Finally, regarding knowledge about the term sharenting (Q7), 41.10% of the participants claim to know what it means, while more than half of the participants, 58.90%, do not know this concept. These results show that, although there is a strong tendency to share content about children on social networks and a positive perception towards such posts, there are still concerns about the associated risks. In addition, most users do not know all of their online contacts and are unaware of the term sharenting, indicating the need for greater awareness of the impact and implications of social media exposure and use on children’s privacy and safety.

Regarding how these results are divided by gender, age or age of children (Figure 3), the data related to knowledge of social network contacts (Q1) reveal that almost half of the parents surveyed reported that they do not know all the people they have added to their profiles. This indicates that much of what they post on their networks can be seen by strangers, in some cases with malicious intentions, which could represent a risk in terms of privacy and digital security. This phenomenon is even more pronounced in the group of middle-aged parents, specifically those aged 31–40, as well as those with young children, aged 0–12. In terms of posting content about their children on social networks (Q2), the following clear trend is observed: more than half of the parents surveyed share photos, videos or other content related to their children. This behaviour is more frequent among parents aged 31–40 and those with children under 12. This practice of sharing images and family moments on social networks raises questions about the exposure of children and the potential risks associated with it.

Regarding the perception of the interaction these posts generate, in particular whether they receive more ‘likes’ when sharing photos with their children compared to individual photos (Q3), the majority of responses indicate that they do not perceive a significant difference. That is, the majority of respondents, regardless of gender, age, or age of their children, consider that their posts with pictures of their children do not generate a higher level of interaction in terms of likes or comments. In relation to liking to see other children’s posts on social networks (Q4), it is evident that the majority of parents respond affirmatively, showing a positive attitude towards this type of content.

However, this trend is not replicated in the group of parents over 50 years of age, who to a greater extent express disinterest or even dislike for this type of publications, which may be related to generational differences in the use of social networks or to a more reserved view of private life (Garrido et al., 2023). On the other hand, when asked whether they have experienced bullying or negative comments as a result of their social media posts (Q5), the vast majority of respondents stated that they have not experienced such harassment, suggesting that, at least in this group, cyberbullying does not seem to be a predominant problem. However, one aspect that generates greater concern among parents is the risk that social networking sites may pose (Q6). A high percentage of study participants (regardless of gender, age and age of children) expressed concern about the potential dangers associated with exposure on these platforms, indicating a growing awareness of the challenges of the digital age in relation to parenting and child safety. Finally, regarding knowledge of the term sharenting—the practice of sharing content about children on social media (Q7)—it was observed that most respondents were unaware of its meaning (Table 2).

Table 2.

%Questions of the graduate’s survey.

Furthermore, responses to the question “Do you know all the contacts you have added to your social networks?” (Q1) were compared with “Do you post content about your children on social media?” (Q2). Statistical analysis yielded a χ2 value of 0.7383, p = 0.3902 (Table 2), indicating the absence of a statistically significant association between the two variables. This suggests that knowing or not knowing all of one’s social media contacts does not significantly influence the decision to post content about minors. On the other hand, the influence of social validation on this behaviour was analysed through the association between receiving interactions such as ‘likes’ and comments on children’s content publications (Q2 vs. Q3). The result obtained was χ2 = 0.0363, p = 0.8489 (Table 3). Since the p-value is considerably high, it is concluded that there is no statistically significant association between receiving more interactions and the publication of children’s content on social networks. Another comparison arises from some users’ enjoyment of consuming content related to the lives of other parents’ children. To assess whether this preference translates into active posting behaviour, we analysed the association between the variable ‘Do you enjoy seeing other parents sharing content about their children on social media?’ (Q4) and ‘Do you post content about your children on social media?’ (Q2). Chi-square analysis of independence yielded a value χ2 = 0.1102, p = 0.7399 (Table 3), indicating that there is no statistically significant association between the two variables. To this end, an analysis of independence was carried out between Q5 and Q2, using the Chi-square test, which yielded a value χ2 = 0.9188, p = 0.3378 (Table 3), showing the lack of a significant statistical association between having been a victim of bullying on networks and the decision to share content about children. To analyse this association, a Chi-square test was performed between variables Q2 and Q6. The statistical analysis yielded a χ2 value = 0.0006, p = 0.9807 (Table 3), indicating that there is no statistically significant association between concern about network risks and the decision to share child content (Table 3).

Table 3.

Chi-square test values.

4. Discussion

The results of this research have allowed us to compare the independent variables with each other in order to analyse the behaviour of parents on social networks. For this purpose, the Chi-square test of independence was used to identify a significant association between the questions studied (Q1, Q2, Q3, Q4, Q5, Q6 and Q7). The results suggest that factors such as perceived privacy and social validation may not be directly related to the decision to share content about children (Kallioharju et al., 2023; Subasi et al., 2024). These findings contribute directly to the fulfilment of the study’s objectives, as they allow us to identify the factors that do or do not influence the digital behaviour of parents with respect to the publication of content about their children, and offer a first approximation to current perceptions of children’s digital privacy in Paraguay.

The level of trust in their digital circle is perceived by parents as one of the factors that might influence the decision to share images, videos, or texts about their children on social networks (Er et al., 2022; Hoffner & Bond, 2022). One might expect parents with less knowledge of their audience to be more cautious about sharing content about their children (Doğan Keskin et al., 2023; Porfírio & Jorge, 2022). However, the data suggest that this perception of risk has no real impact on their behaviour. This could be due to trust in the privacy settings of social networks or the normalisation of sharenting as a form of socialising on digital platforms (Ferrara et al., 2023; Walrave et al., 2023).

Therefore, the motivation behind sharenting does not appear to be driven by social interaction, although in other contexts, the amount of social media interactions may influence users’ behaviour; the results suggest that this is not a determining factor in the posting of content about children. This could indicate that parents who engage in sharenting do so for personal or emotional reasons, such as a desire to share family moments with friends and family, rather than to seek external approval (Colapietro & Iannuzzi, 2024). This conclusion responds directly to the specific objective of assessing the impact of social validation on digital parental behaviour, showing that visibility or popularity on networks is not relevant to this practice.

This suggests that viewing content shared by other families is a passive experience for many users, with no incentive to replicate that behaviour (Garrido et al., 2023; Orhan Kılıç et al., 2024b). This finding advances the goal of identifying patterns and trends in parents’ digital behaviour, as well as the real motivations behind sharenting, beyond exposure to other people’s content.

Due to the current incidence of cyberbullying, we analysed whether previous experiences of cyberbullying can influence the way in which parents manage their children’s digital presence. Furthermore, the normalisation of sharenting could minimise the perception of risk, even when one has been a victim of cyberbullying (Kumar & Schoenebeck, 2015). These results are relevant for the purpose of assessing the level of agreement about the risks associated with sharenting, reflecting a disconnect between previous negative experiences and digital preventive behaviours.

Finally, in a context where digital safety is a growing concern, it was hypothesised that parents who are concerned about the risks of social networks would be less likely to share images, videos or information about their children in these spaces (Walrave et al., 2023). This may indicate that sharenting is not perceived as a practice that may carry significant risks to children’s privacy. This suggests that knowledge about the potential dangers of network exposure is not a determining factor in the practice of sharenting. It is possible that the risks are perceived in a general sense, not directly related to the posting of child content (Er et al., 2022). Furthermore, the normalisation of children’s exposure to social media may contribute to a lower perception of risk, even if they are aware of the general dangers of the digital environment (Blum-Ross & Livingstone, 2017). In this sense, this analysis explores parents’ level of knowledge about the risks of sharenting and its impact on children’s privacy, revealing an apparent dissociation between perception and practice.

5. Conclusions

The results obtained demonstrate the need to strengthen awareness about digital privacy and social media security. Although no direct association was observed between knowing one’s contacts and sharing children’s content, this does not mean that the information posted is risk-free. It is essential that parents receive digital education to understand the implications of exposing images of their children online, regardless of the composition of their contact list.

Furthermore, the data rule out the hypothesis that parents post content about their children in order to gain more engagement. This suggests that sharenting responds to different motivations, possibly related to the family environment and digital culture, rather than the search for social validation. Furthermore, the lack of relationship between the enjoyment of consuming posts about children and the decision to share children’s content indicates that this practice does not depend solely on a preference for this type of posting, but rather involves more complex factors. Factors such as perceptions of security, privacy, and individual norms of digital exposure appear to play a more relevant role in the decision to share images of minors on social media.

Another relevant finding is the significant absence of parents who have been victims of cyberbullying in their decision to post photos of their children. This raises questions about the perception of digital risk and the lack of awareness about the potential implications of children’s online exposure. Along these lines, future research must delve deeper into how negative online experiences affect users’ decisions regarding digital privacy and security, in order to design effective awareness-raising and sharenting prevention strategies.

Similarly, the results suggest that, although the majority of respondents express concern about the risks of social media, this does not translate into a reduction in the practice of sharing children’s content. This discrepancy between risk perception and the implementation of preventive measures highlights the need to promote more effective digital education strategies. Not only should information be provided about the general dangers of the internet, but the implications of sharenting should also be specifically addressed, encouraging more responsible use of children’s digital identities.

Finally, future research could delve deeper into the motivations behind this practice, assessing variables such as risk perception, trust in digital platforms, and generational differences in social media use. These aspects would allow for a more detailed understanding of the psychological and social factors that influence parents’ decisions to share content about their children online.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.N.-S. and N.B.P.M.; methodology, M.N.-S. and M.S.-J.; software, M.S.-J.; validation, M.N.-S., M.S.-J. and N.B.P.M.; formal analysis, M.S.-J.; investigation, M.N.-S. and N.B.P.M.; data curation, M.N.-S. and M.S.-J.; writing—original draft preparation, M.N.-S. and N.B.P.M.; writing—review and editing, M.N.-S. and M.S.-J.; visualization, M.N.-S., M.S.-J. and N.B.P.M.; supervision, M.N.-S., M.S.-J. and N.B.P.M.; project administration, M.N.-S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Junta de Castilla y León and the Ethics Committee of the University of Salamanca (protocol code 351 and date of approval 6 February 2019).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data are not public due to confidentiality reasons. They may be provided upon a reasoned request to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Baxter, K., & Czarnecka, B. (2025). Sharing images of children on social media: British motherhood influencers and the privacy paradox. PLoS ONE, 20(1), e0314472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bayraktar, F., & Çelik, D. (2024). The mediating role of social comparison between parental self-efficacy and sharenting. Turkish Journal of Psychiatry, 36, 216–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello, B. G. (2025). Digital technologies and children’s rights: Balancing control, protection, and consent. Revista de Derecho Privado, 48, 19–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, V., Arabiat, D., Morelius, E., Kervin, L., Zgambo, M., Robinson, S., Jenkins, M., & Whitehead, L. (2024). Young children and the creation of a digital identity on social networking sites: Scoping review. JMIR Pediatrics and Parenting, 7, e54414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beuckels, E., Hudders, L., Vanwesenbeeck, I., & Van den Abeele, E. (2024). Work it baby! A survey study to investigate the role of underaged children and privacy management strategies within parent influencer content. New Media & Society. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blum-Ross, A., & Livingstone, S. (2017). “Sharenting,” parent blogging, and the boundaries of the digital self. Popular Communication, 15(2), 110–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozzola, E., Spina, G., Agostiniani, R., Barni, S., Russo, R., Scarpato, E., Di Mauro, A., Di Stefano, A. V., Caruso, C., Corsello, G., & Staiano, A. (2022). The use of social media in children and adolescents: Scoping review on the potential risks. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(16), 9960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burn, E. (2022). #warriors: Sick children, social media and the right to an open future. Journal Medical Ethics, 48(8), 566–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantín, M. (2014). Declaración de helsinki de la asociación médica mundial: Principios éticos para las investigaciones médicas en seres humanos. International Journal of Medical and Surgical Sciences, 1(4), 339–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colapietro, C., & Iannuzzi, A. (2024). I diritti dei minori nella società digitale tra profili di responsabilità ed esigenze di protezione. Rivista Italiana di Informatica e Diritto, 6(2), 333–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conti, M. G., Del Parco, F., Pulcinelli, F. M., Mancino, E., Petrarca, L., Nenna, R., Di Mattia, G., Matera, L., La Regina, D., Bonci, E., Caruso, C., & Midulla, F. (2024). Sharenting: Characteristics and awareness of parents publishing sensitive content of their children on online platforms. Italian Journal of Pediatrics, 50(1), 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Çimke, S., Yıldırım Gürkan, D., & Polat, S. (2018). Sosyal medyada çocuk hakkı ihlali: Sharenting. Güncel Pediatri, 16(2), 261–267. Available online: https://dergipark.org.tr/tr/download/article-file/518497 (accessed on 17 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Doğan Keskin, A., Kaytez, N., Damar, M., Elibol, F., & Aral, N. (2023). Sharenting syndrome: An appropriate use of social media? Healthcare, 11(10), 1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Er, S., Yılmaztürk, N. H., Özgül, T., & Çok, F. (2022). Parents’ shares on Instagram in the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic. Turkish Journal of Education, 11(1), 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Alfaraz, M.-L., Nieto-Sobrino, M., Antón-Sancho, Á., & Vergara, D. (2023). Perception of Bullying in Early Childhood Education in Spain: Pre-School Teachers vs. Psychologists. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 13(3), 655–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrara, P., Cammisa, I., Corsello, G., Giardino, I., Vural, M., Pop, T. L., Pettoello-Mantovani, C., Indrio, F., & Pettoello-Mantovani, M. (2023). Online “Sharenting”: The dangers of posting sensitive information about children on social media. The Journal of Pediatrics, 257, 113322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrara, P., Cammisa, I., Zona, M., Cimaroli, E., Sacco, R., Pacucci, I., Grimaldi, M. T., Scaltrito, F., Pettoello-Mantovani, M., & Corsello, G. (2024). The awareness of sharenting in Italy: A pilot study. Italian The Journal of Pediatrics, 50, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido, F., Alvarez, A., González-Caballero, J. L., Garcia, P., Couso, B., Iriso, I., Merino, M., Raffaeli, G., Sanmiguel, P., Arribas, C., Vacaroaia, A., & Cavallaro, G. (2023). Description of the exposure of the most-followed spanish instamoms’ children to social media. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(3), 2426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, T. T., & Dayan, S. H. (2020). How to leverage social media in private practice. Facial Plastic Surgery Clinics of North America, 28(4), 515–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffner, C. A., & Bond, B. J. (2022). Parasocial relationships, social media, & well-being. Current Opinion in Psychology, 45, 101306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallioharju, M., Wilska, T.-A., & Vänskä, A. (2023). Mothers’ self-representations and representations of childhood on social media. Young Consumers, 24(4), 485–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, G. K., Ow Yong, J. Q. Y., Lee, A. R. Y. B., Ong, B. S. Y., Yau, C. E., Ho, C. S. H., & Goh, Y. S. (2024). Social media use and its impact on adults’ mental health and well-being: A scoping review. Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing, 21(4), 345–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P., & Schoenebeck, S. (2015, March 14–18). The modern day baby book: Enacting good mothering and stewarding privacy on Facebook. CSCW ‘15: 18th ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work & Social Computing (pp. 1302–1312), Vancouver, BC, Canada. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litchfield, I., Shukla, D., & Greenfield, S. (2021). Impact of COVID-19 on the digital divide: A rapid review. BMJ Open, 11, e053440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longobardi, C., Fabris, M. A., Prino, L. E., & Settanni, M. (2021). Online sexual victimization among middle school students: Prevalence and association with online risk behaviors. International Journal of Developmental Science, 15(1–2), 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo Laclote, P., Martínez-Líbano, J., Céspedes, C., Fuentealba-Urra, S., Ramírez, N. S., Lara, R. I., & Yeomans-Cabrera, M.-M. (2025). Grooming risk factors in adolescents with abuse histories: Insights from chilean reparative programs. Adolescents, 5(1), 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieto-Sobrino, M., Díaz, D., García-Mateos, M., Antón-Sancho, Á., & Vergara, D. (2023). Incidence of bullying in sparsely populated regions: An exploratory study in Ávila and Zamora (Spain). Education Sciences, 13(2), 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orhan Kiliç, B., Kiliç, S., Konuksever, D., & Ulukol, B. (2024a). The relationship between mothers’ Instagram follower count and the concept of sharenting. Pediatrics International, 66(1), e15736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orhan Kılıç, B., Kılıç, S., & Ulukol, B. (2024b). Exploring the relationship between social media use, sharenting practices, and maternal psychological well-being. Archives de Pédiatrie, 31(8), 519–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedrouzo, S. B., & Krynski, L. (2023). Hyperconnected: Children and adolescents on social media. The TikTok phenomenon. Archivos Argentinos de Pediatría, 121(4), e202202674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peimanpak, F., Abdollahi, A., Allen, K. A., Rakhmatova, F. A., Aladini, A., Alshahrani, S. H., & Brewer, J. (2023). Validation of the online version of the sharenting evaluation scale (SES) in Iranian parents: Psychometric properties and concurrent validity. Brain and Behavior, 13(12), e3300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porfírio, F., & Jorge, A. (2022). Sharenting of portuguese male and female celebrities on instagram. Journalism and Media, 3(3), 521–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rachman, A., Verawati, I., & Rusandi, M. A. (2023). Understanding ‘flexing’: The impact on mental health and public trust. Journal of Public Health, 45(4), 806–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajamohan, S., Bennett, E., & Tedone, D. (2019). The hazards and benefits of social media use in adolescents. Nursing, 49(11), 52–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, J., Das, P., Muthiah, N., & Milanaik, R. (2019). New age technology and social media: Adolescent psychosocial implications and the need for protective measures. Current Opinion in Pediatrics, 31(1), 148–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivak, E., & Smirnov, I. (2019). Parents mention sons more often than daughters on social media. Proceeding of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA, 116(6), 2039–2041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staes, L., Walrave, M., & Hallam, L. (2023). Grandsharenting: Cómo los abuelos en Bélgica negocian la divulgación de información personal sobre sus nietos y aplican estrategias de gestión de la privacidad en Facebook. Journal of Children and Media, 17(2), 192–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subasi, S., Korkmaz, Ö., & Kukul, V. (2024). Social media parenting scale: Validity and reliability study. Education and Information Technologies, 29(18), 25093–25121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venegas-Vera, A. V., Colbert, G. B., & Lerma, E. V. (2020). Positive and negative impact of social media in the COVID-19 era. Reviews in Cardiovascular Medicine, 21(4), 561–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walrave, M., Robbé, S., Staes, L., & Hallam, L. (2023). Mindful sharenting: How millennial parents balance between sharing and protecting. Frontiers in Psychology, 25(14), 1171611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).