Awakened Awareness Online: Results from an Open Trial of a Spiritual–Mind–Body Wellness Intervention for Remote Undergraduate Students

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Remote Wellness Resources

1.2. Barriers to Mental Health Services for SGM Students

1.3. Spirituality and Its Protective Effects on Mental Health

1.4. Awakened Awareness for Adolescents

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedures

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Clinical Symptoms

2.2.2. Spiritual Well-Being

2.2.3. Affordances and Constraints

2.3. Data Analysis

2.3.1. Feasibility

2.3.2. Acceptability

2.3.3. Pre-Post Intervention Changes

2.3.4. SGM Status and Delivery Method

3. Results

3.1. Feasibility

3.2. Acceptability

Being in person is important to me and I think it would have been easier to cultivate relationships from it that way…I thought it was so helpful and I got to know people, [but] it doesn’t have that element of showing up early so you chit chat or after you leave people stay behind and chit chat. I think that those tiny elements really do change the way the program works.

This specific group has allowed me to meet people that go to my school that I really don’t think I would be meeting otherwise. It’s given me an avenue to have social interaction…It’s an hour and a half with this intimate group of people that I feel comfortable with, it’s very nice just having that safe space.

3.3. Pre-Post Intervention Changes

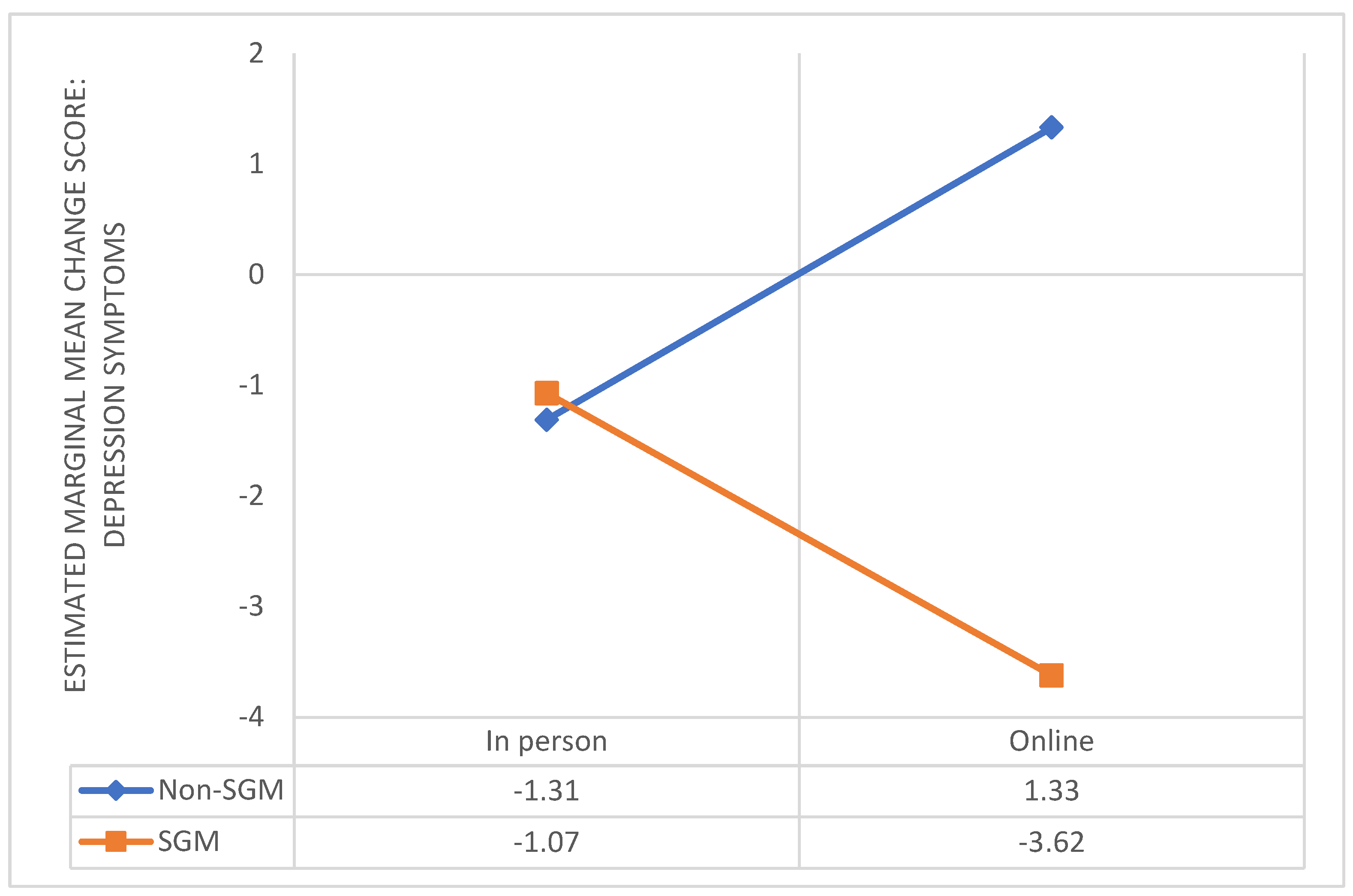

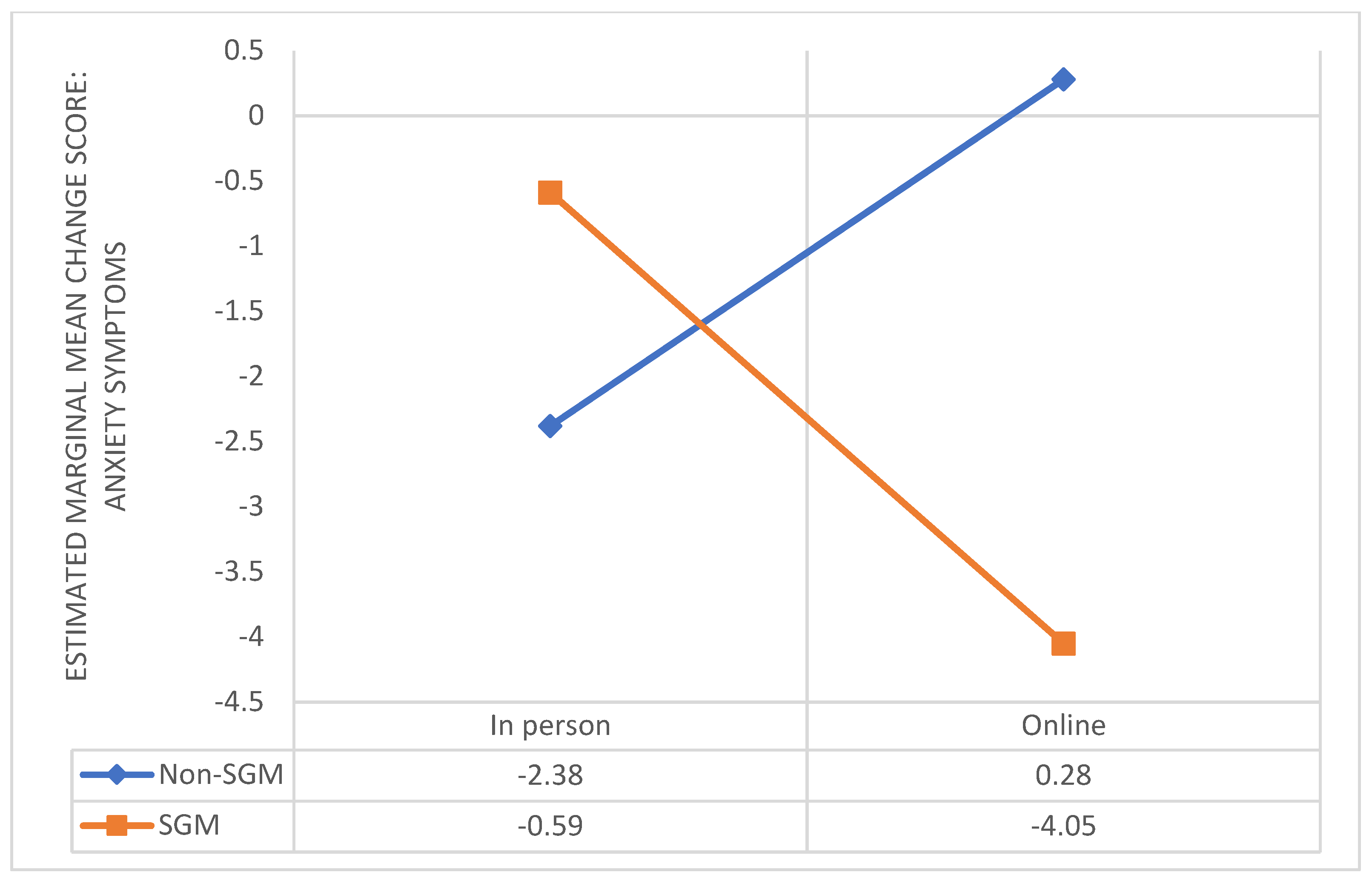

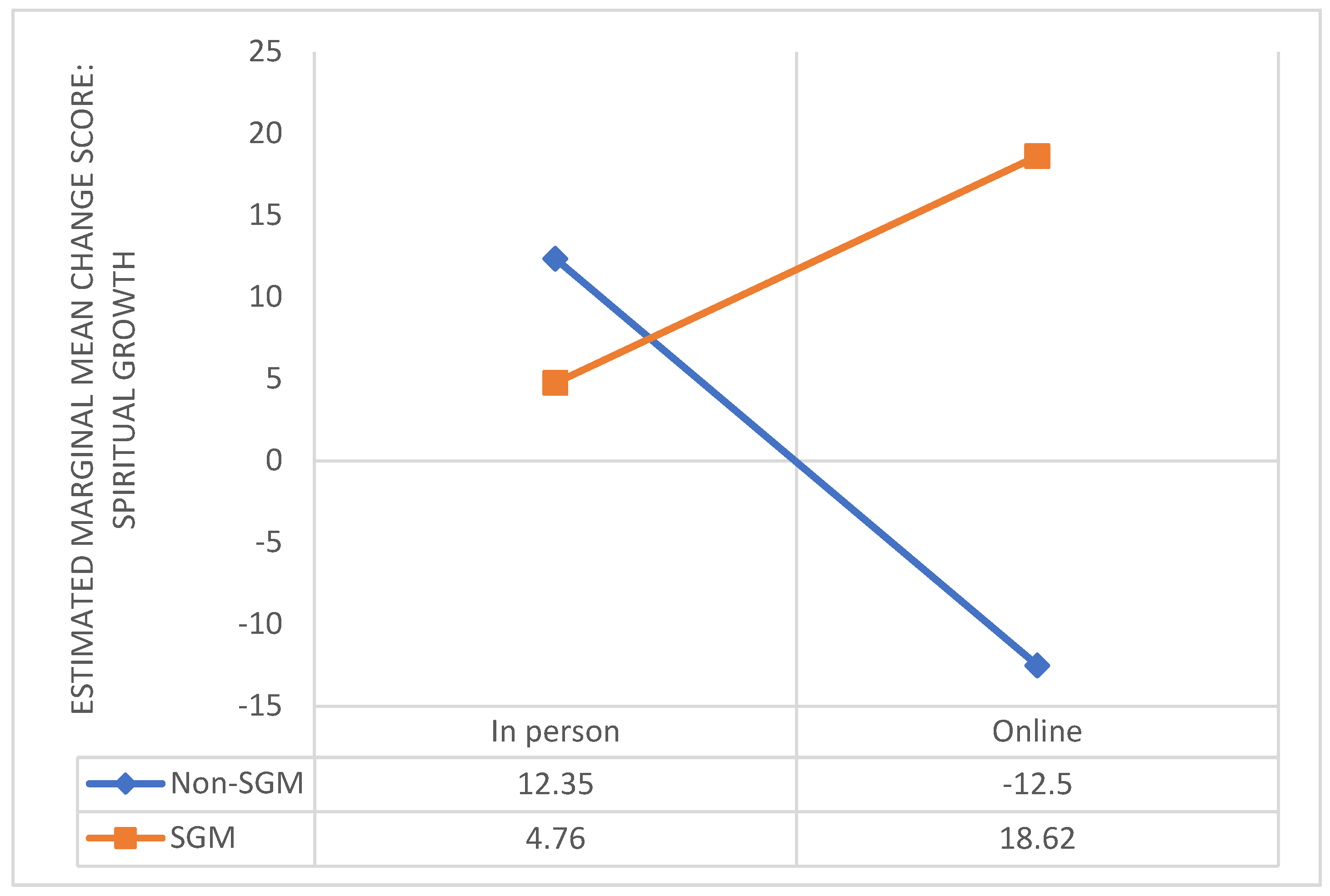

3.4. SGM Status and Delivery Method

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Anderson, M. R., Scalora, S. C., Crete, A., Mistur, E. J., & Miller, L. (2023). Physiological recovery from stress is associated with spiritual recovery: Findings from Awakened Awareness, a college-based spiritual-mind-body intervention. Integrative Medicine Reports, 2, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, A., Craig, S. L., Navega, N., & McInroy, L. B. (2020). It’s my safe space: The life-saving role of the internet in the lives of transgender and gender diverse youth. International Journal of Transgender Health, 21, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barr, B. (2014). Identifying and addressing the mental health needs of online students in higher education. Online Journal of Distance Learning Administration, 17, 35–40. [Google Scholar]

- Barton, Y. A., Barkin, S. H., & Miller, L. (2017). Deconstructing depression: A latent profile analysis of potential depressive subtypes in emerging adults. Spirituality in Clinical Practice, 4(1), 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beraldo, L., Gil, F., Ventriglio, A., de Andrade, A. G., da Silva, A. G., Torales, J., Gonçalves, P. D., Bhugra, D., & Castaldelli-Maia, J. M. (2019). Spirituality, religiosity and addiction recovery: Current perspectives. Current Drug Research Reviews, 11, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, B. J., & Miller, B. (2024). YouTube as my space: The relationships between YouTube, social connectedness, and (collective) self-esteem among LGBTQ individuals. New Media & Society, 26(1), 513–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonelli, R., Dew, R. E., Koenig, H. G., Rosmarin, D. H., & Vasegh, S. (2012). Religious and spiritual factors in depression: Review and integration of the research. Depression Research and Treatment, 2012(1), 962860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breitbart, W., Pessin, H., Rosenfeld, B., Applebaum, A. J., Lichtenthal, W. G., Li, Y., Saracino, R. M., Marziliano, A. M., Masterson, M., Tobias, K., & Fenn, N. (2018). Individual meaning-centered psychotherapy for the treatment of psychological and existential distress: A randomized controlled trial in patients with advanced cancer. Cancer, 124(15), 3231–3239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Captari, L. E., Hook, J. N., Hoyt, W., Davis, D. E., McElroy-Heltzel, S. E., & Worthington, E. L., Jr. (2018). Integrating clients’ religion and spirituality within psychotherapy: A comprehensive meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 74(11), 1938–1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavanagh, K., Strauss, C., Cicconi, F., Griffiths, N., Wyper, A., & Jones, F. (2013). A randomised controlled trial of a brief online mindfulness-based intervention. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 51(9), 573–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, C., Ying Ho, P. S., & Chow, E. (2002). A body-mind-spirit model in health: An Eastern approach. Social Work in Health Care, 34(3–4), 261–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, T., & Wong, R. P. (2011). Using the internet to provide support, psychoeducation, and self-help to Asian American men. In Culturally responsive counseling with Asian American men (pp. 281–300). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, T., & Yeh, C. J. (2003). Using Online Groups to Provide Support to Asian American Men: Racial, Cultural, Gender, and Treatment Issues. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 34, 634–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, T., Yeh, C. J., & Krumboltz, J. D. (2001). Process and outcome evaluation of an on-line support group for Asian American male college students. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 48(3), 319–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, V., Braun, V., & Hayfield, N. (2015). Thematic analysis. In J. A. Smith (Ed.), Qualitative psychology: A practical guide to research methods (pp. 222–248). SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Cole, B. S., Hopkins, C. M., Tisak, J., Steel, J. L., & Carr, B. I. (2008). Assessing spiritual growth and spiritual decline following a diagnosis of cancer: Reliability and validity of the spiritual transformation scale. Psycho-Oncology: Journal of the Psychological, Social and Behavioral Dimensions of Cancer, 17(2), 112–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, S. L., & McInroy, L. (2014). You can form a part of yourself online: The influence of new media on identity development and coming out for LGBTQ youth. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Mental Health, 18(1), 95–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cranford, J. A., Eisenberg, D., & Serras, A. M. (2009). Substance use behaviors, mental health problems, and use of mental health services in a probability sample of college students. Addictive Behaviors, 34(2), 134–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crete, A., Scalora, S., Mistur, E., Anderson, & Miller, L. (2025). Spiritual growth and mental health gains: Benefits of awakened awareness for college students at three-month follow-up [Manuscript Submitted for Publication, Department of Counseling and Clinical Psychology, Teachers College, Columbia Univeristy]. [Google Scholar]

- Čepulienė, A. A., & Skruibis, P. (2022). The role of spirituality during suicide bereavement: A qualitative study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(14), 8740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delaney, C. (2005). The Spirituality Scale: Development and psychometric testing of a holistic instrument to assess the human spiritual dimension. Journal of Holistic Nursing, 23, 145–167; discussion 68–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunbar, M. S., Sontag-Padilla, L., Ramchand, R., Seelam, R., & Stein, B. D. (2017). Mental health service utilization among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and questioning or queer college students. Journal of Adolescent Health, 61(3), 294–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Morr, C., Ritvo, P., Ahmad, F., Moineddin, R., & MVC Team. (2020). Effectiveness of an 8-week web-based mindfulness virtual community intervention for university students on symptoms of stress, anxiety, and depression: Randomized controlled trial. JMIR Mental Health, 7(7), e18595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eloff, I. (2021). College students’ well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic: An exploratory study. Journal of Psychology in Africa, 31(3), 254–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Exline, J. J., Hall, T. W., Pargament, K. I., & Harriott, V. A. (2017). Predictors of growth from spiritual struggle among Christian undergraduates: Religious coping and perceptions of helpful action by God are both important. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 12(5), 501–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenzel, L. M., & Richardson, K. D. (2022). The stress process among emerging adults: Spirituality, mindfulness, resilience, and self-compassion as predictors of life satisfaction and depressive symptoms. Journal of Adult Development, 29(1), 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firestone, J., Cardaciotto, L., Levin, M. E., Goldbacher, E., Vernig, P., & Gambrel, L. E. (2019). A web-based self-guided program to promote valued-living in college students: A pilot study. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 12, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer-Grote, L., Fössing, V., Aigner, M., Fehrmann, E., & Boeckle, M. (2024). Effectiveness of online and remote interventions for mental health in children, adolescents, and young adults after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic: Systematic review and meta-analysis. JMIR Mental Health, 11, e46637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fish, J. N., McInroy, L. B., Paceley, M. S., Williams, N. D., Henderson, S., Levine, D. S., & Edsall, R. N. (2020). “I’m kinda stuck at home with unsupportive parents right now”: LGBTQ youths’ experiences with COVID-19 and the importance of online support. Journal of Adolescent Health, 67(3), 450–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garlow, S. J., Rosenberg, J., Moore, J. D., Haas, A. P., Koestner, B., Hendin, H., & Nemeroff, C. B. (2008). Depression, desperation, and suicidal ideation in college students: Results from the American foundation for suicide prevention college screening project at Emory University. Depression and Anxiety, 25(6), 482–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, J. P., Lucchetti, G., Menezes, P. R., & Vallada, H. (2015). Religious and spiritual interventions in mental health care: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled clinical trials. Psychological Medicine, 45(14), 2937–2949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzales, G., de Mola, E. L., Gavulic, K. A., McKay, T., & Purcell, C. (2020). Mental health needs among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender college students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Adolescent Health, 67(5), 645–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhow, C., & Chapman, A. (2020). Social distancing meet social media: Digital tools for connecting students, teachers, and citizens in an emergency. Information and Learning Sciences, 121(5/6), 341–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhow, C., & Galvin, S. (2020). Teaching with social media: Evidence-based strategies for making remote higher education less remote. Information and Learning Sciences, 121(7/8), 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdan, S., & Hallaq, E. (2021). Prolonged exposure to violence: Psychiatric symptoms and suicide risk among college students in the Palestinian territory. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 13(7), 772–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hart, A. C., Pargament, K. I., Grubbs, J. B., Exline, J. J., & Wilt, J. A. (2020). Predictors of self-reported growth following religious and spiritual struggles: Exploring the role of wholeness. Religions, 11(9), 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healthy Minds Network. (2024). Healthy minds study among colleges and universities, 2023–2024. Winter/Spring Data Report. Healthy Minds Network. [Google Scholar]

- Holt, M. K., Greif Green, J., Reid, G., DiMeo, A., Espelage, D. L., Felix, E. D., Furlong, M. J., Poteat, V. P., & Sharkey, J. D. (2014). Associations between past bullying experiences and psychosocial and academic functioning among college students. Journal of American College Health, 62(8), 552–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ierardi, E., Bottini, M., & Riva Crugnola, C. (2022). Effectiveness of an online versus face-to-face psychodynamic counselling intervention for university students before and during the COVID-19 period. BMC Psychology, 10(1), 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, S. D. (2017). “Connection is the antidote”: Psychological distress, emotional processing, and virtual community building among LGBTQ students after the Orlando shooting. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 4(2), 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., & Williams, J. B. (2001). The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 16(9), 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J., Jeong, H. J., & Kim, S. (2021). Stress, anxiety, and depression among undergraduate students during the COVID-19 pandemic and their use of mental health services. Innovative Higher Education, 46, 519–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, M. E., Stocke, K., Pierce, B., & Levin, C. (2018). Do college students use online self-help? A survey of intentions and use of mental health resources. Journal of College Student Psychotherapy, 32(3), 181–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K. K., & Chow, W. Y. (2015). Religiosity/spirituality and prosocial behaviors among Chinese Christian adolescents: The mediating role of values and gratitude. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 7(2), 150–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipson, S. K., Kern, A., Eisenberg, D., & Breland-Noble, A. M. (2018). Mental health disparities among college students of color. Journal of Adolescent Health, 63(3), 348–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipson, S. K., Zhou, S., Abelson, S., Heinze, J., Jirsa, M., Morigney, J., Patterson, A., Singh, M., & Eisenberg, D. (2022). Trends in college student mental health and help-seeking by race/ethnicity: Findings from the national healthy minds study, 2013–2021. Journal of Affective Disorders, 306, 138–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lister, K., Seale, J., & Douce, C. (2023). Mental health in distance learning: A taxonomy of barriers and enablers to student mental wellbeing. Open Learning: The Journal of Open, Distance and e-Learning, 38(2), 102–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C. H., Zhang, E., Wong, G. T. F., & Hyun, S. (2020). Factors associated with depression, anxiety, and PTSD symptomatology during the COVID-19 pandemic: Clinical implications for US young adult mental health. Psychiatry Research, 290, 113172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, A., & Nguyen, S. (2020). The impact of COVID-19 on college student well-being. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10919/99741 (accessed on 9 January 2023).

- Mastropieri, B., Schussel, L., Forbes, D., & Miller, L. (2015). Inner resources for survival: Integrating interpersonal psychotherapy with spiritual visualization with homeless youth. Journal of Religion and Health, 54, 903–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAleavey, A. A., Castonguay, L. G., & Locke, B. D. (2011). Sexual orientation minorities in college counseling: Prevalence, distress, and symptom profiles. Journal of College Counseling, 14(2), 127–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClintock, C. H., Worhunsky, P. D., Balodis, I. M., Sinha, R., Miller, L., & Potenza, M. N. (2019). How spirituality may mitigate against stress and related mental disorders: A review and preliminary neurobiological evidence. Current Behavioral Neuroscience Reports, 6(4), 253–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenzie, L. (2021, April 26). Students want online learning options post-pandemic. Inside Higher Ed. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, L. (2011). An experiential approach for exploring spirituality. In J. D. Aten, M. R. McMinn, & E. L. Worthington (Eds.), Spiritually oriented interventions for counseling and psychotherapy (pp. 325–343). American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, L. (2013). Spiritual awakening and depression in adolescents: A unified pathway or “two sides of the same coin”. Bulletin of the Menninger Clinic, 77, 332–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, L. (2016). The spiritual child: The new science on parenting for health and lifelong thriving. Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, L. (2021). The awakened brain: The new science of spirituality and our quest for an inspired life. Penguin Random House. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, L., Balodis, I. M., McClintock, C. H., Xu, J., Lacadie, C. M., Sinha, R., & Potenza, M. N. (2019). Neural correlates of personalized spiritual experiences. Cerebral Cortex, 29(6), 2331–2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, L., & Barton, Y. A. (2015). Developmental depression in adolescents: A potential sub-type based on neural correlates and comorbidity. Journal of Religion and Health, 54(3), 817–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, L., Davies, M., & Greenwald, S. (2000). Religiosity and substance use and abuse among adolescents in the National Comorbidity Survey. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 39(9), 1190–1197. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, L., Warner, V., Wickramaratne, P., & Weissman, M. (1997). Religiosity and depression: Ten-year follow-up of depressed mothers and offspring. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 36(10), 1416–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mistur, E. J., Scalora, S. C., Crete, A. A., Anderson, M. R., Athan, A. M., Chapman, A. L., & Miller, L. J. (2022). Inner peace in a global crisis: A case study of supported spiritual individuation in acute onset phase of COVID-19. Emerging Adulthood, 10(6), 1543–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mistur, E. J., Scalora, S. C., Crete, A. A., Anderson, M. R., Jain, K., Huang, C., Noumair, D. A., & Miller, L. (2024). Supporting sexual and gender minority college student wellness: Differential needs and outcomes in a spiritual–mind–body intervention. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity. Advanced online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, S. M., Jackson, H., Sepeda, N. D., Mathai, D. S., So, S., Yaffe, A., Zaki, H., Brasher, T. J., Lowe, M. X., Jolly, D. R. P., & Garcia-Romeu, A. (2023). Naturalistic psilocybin use is associated with persisting improvements in mental health and wellbeing: Results from a prospective, longitudinal survey. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 14, 1199642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen-Feng, V. N., Greer, C. S., & Frazier, P. (2017). Using online interventions to deliver college student mental health resources: Evidence from randomized clinical trials. Psychological Services, 14(4), 481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Office of the U.S. Surgeon General. (2021). Protecting youth mental health: The US Surgeon General’s advisory. Office of the US Surgeon General.

- Paloutzian, R. F., & Park, C. L. (Eds.). (2014). Handbook of the psychology of religion and spirituality. Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Pandya, S. P. (2021). Intervention outcomes, anxiety, self-esteem, and self-efficacy with DHH students in universities. The Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 26(1), 58–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pender, N. J., Murdaugh, C. L., & Parsons, M. A. (2006). Health promotion in nursing practice (p. 367). Pearson Education, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Pretorius, C., Chambers, D., & Coyle, D. (2019). Young people’s online help-seeking and mental health difficulties: Systematic narrative review. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 21(11), e13873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radwan, A. (2022). The post-pandemic future of higher education. Dean and Provost, 23(6), 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, E. C., Arpan, L., Oehme, K., Perko, A., & Clark, J. (2021). Helping students cope with adversity: The influence of a web-based intervention on students’ self-efficacy and intentions to use wellness-related resources. Journal of American College Health, 69(4), 444–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Read, J. P., Griffin, M. J., Wardell, J. D., & Ouimette, P. (2014). Coping, PTSD symptoms, and alcohol involvement in trauma-exposed college students in the first three years of college. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 28(4), 1052–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosmarin, D. H., Kaufman, C. C., Ford, S. F., Keshava, P., Drury, M., Minns, S., Marmarosh, C., Chowdhury, A., & Sacchet, M. D. (2022). The neuroscience of spirituality, religion, and mental health: A systematic review and synthesis. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 156, 100–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggiero, K. J., Ben, K. D., Scotti, J. R., & Rabalais, A. E. (2003). Psychometric properties of the PTSD Checklist—Civilian version. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 16, 495–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, M. L., Shochet, I. M., & Stallman, H. M. (2010). Universal online interventions might engage psychologically distressed university students who are unlikely to seek formal help. Advances in Mental Health, 9(1), 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saldaña, J. (2021). The coding manual for qualitative researchers (4th ed.). SAGE Publishing Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Salimi, N., Gere, B., Talley, W., & Irioogbe, B. (2023). College students mental health challenges: Concerns and considerations in the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of College Student Psychotherapy, 37(1), 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scalora, S., Anderson, M., Crete, A., Drapkin, J., Portnoff, L., Athan, A., & Miller, L. (2020). A spirituality mind-body wellness center in a university setting; A pilot service assessment study. Religions, 11(9), 466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scalora, S. C., Anderson, M. R., Crete, A., Mistur, E. J., Chapman, A., & Miller, L. (2022). A campus-based spiritual-mind-body prevention intervention against symptoms of depression and trauma; an open trial of Awakened Awareness. Mental Health & Prevention, 25, 200229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheer, S. B., & Lockee, B. B. (2003). Addressing the wellness needs of online distance learners. Open Learning: The Journal of Open, Distance and e-Learning, 18(2), 177–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidel, E. J., Mohlman, J., Basch, C. H., Fera, J., Cosgrove, A., & Ethan, D. (2020). Communicating mental health support to college students during COVID-19: An exploration of website messaging. Journal of Community Health, 45, 1259–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahina, G., & Parveen, A. (2020). Role of spirituality in building up resilience and mental health among adolescents. Indian Journal of Positive Psychology, 11(4), 392–397. [Google Scholar]

- Sperry, L. (2018). Mindfulness, soulfulness, and spiritual development in spiritually oriented psychotherapy. Spirituality in Clinical Practice, 5(4), 291–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitzer, R. L., Kroenke, K., Williams, J. B., & Löwe, B. (2006). A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD-7. Archives of Internal Medicine, 166(10), 1092–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sriati, A., Kurniawan, K., Senjaya, S., Khoirunnisa, K., Muslim, R. N. I., Putri, A. M., Aghnia, N., & Fitriani, N. (2024). The effectiveness of digital-based psychotherapy in overcoming psychological problems in college students during the COVID-19 pandemic: A scoping review. Journal of Holistic Nursing, 42(Suppl. S2), S26–S39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuifbergen, A. K., Morris, M., Jung, J. H., Pierini, D., & Morgan, S. (2010). Benefits of wellness interventions for persons with chronic and disabling conditions: A review of the evidence. Disability and Health Journal, 3(3), 133–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swarbrick, M. (2006). A wellness approach. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 29(4), 311–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, and Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS). (2018). Number and percentage of undergraduate students enrolled in distance education or online classes and degree programs, by selected characteristics: Selected years, 2003–2004 through 2015–2016. In Digest of Education Statistics. U.S. Department of Education. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, and Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS). (2021). Number and percentage of students enrolled in degree-granting postsecondary institutions, by distance education participation, location of student, level of enrollment, and control and level of institution: Fall 2018 and Fall 2019. In Digest of Education Statistics. U.S. Department of Education. [Google Scholar]

- Vinothkumar, M. (2015). Adolescence psychological well-being in relation to spirituality and pro-social behaviour. Indian Journal of Positive Psychology, 6(4), 361–366. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, R., Chen, F., Chen, Z., Li, T., Harari, G., Tignor, S., Zhou, X., Ben-Zeev, D., & Campbell, A. T. (2014, September 13–17). StudentLife: Assessing mental health, academic performance and behavioral trends of college students using smartphones. 2014 ACM International Joint Conference on Pervasive and Ubiquitous Computing (pp. 3–14), Seattle, WA, USA. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, D. C., & Jefferson, S. O. (2013). Recommendations for the use of online social support for African American men. Psychological Services, 10(3), 323–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weathers, F. W., Litz, B. T., Herman, D. S., Huska, J. A., & Keane, T. M. (1993, October 24). The PTSD Checklist (PCL): Reliability, validity, and diagnostic utility. Annual Convention of the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies (Vol. 462, ), San Antonio, TX, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, D. (2020). Examining the impact mindfulness meditation on measures of mindfulness, academic self–efficacy, and gpa in online and on–ground learning environments. Journal of Transformative Learning, 7(2), 71–86. [Google Scholar]

- Wotto, M. (2020). The future high education distance learning in Canada, the United States, and France: Insights from before COVID-19 secondary data analysis. Journal of Educational Technology Systems, 49(2), 262–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapata-Ospina, J. P., Patiño-Lugo, D. F., Vélez, C. M., Campos-Ortiz, S., Madrid-Martínez, P., Pemberthy-Quintero, S., Pérez-Gutiérrez, A. M., Ramírez-Pérez, P. A., & Vélez-Marín, V. M. (2021). Mental health interventions for college and university students during the COVID-19 pandemic: A critical synthesis of the literature. Revista Colombiana de Psiquiatria (English ed.), 50(3), 199–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, X., Edirippulige, S., Bai, X., & Bambling, M. (2021). Are online mental health interventions for youth effective? A systematic review. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare, 27(10), 638–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Participated Online | Participated in Person | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | n (%) | /n | n (%) | /n |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 3 (8%) | 39 | 12 (15.6%) | 77 |

| Female | 32 (82%) | 39 | 62 (80.5%) | 77 |

| Transgender and non-binary | 4 (10.3%) | 39 | 3 (3.9%) | 77 |

| Sexual orientation | ||||

| Heterosexual | 18 (46%) | 39 | 48 (62.3%) | 77 |

| Gay/Lesbian | 6 (15%) | 39 | 6 (7.8%) | 77 |

| Bisexual | 9 (23%) | 39 | 16 (20.8%) | 77 |

| Questioning | 5 (13%) | 39 | 2 (2.6%) | 77 |

| Queer/Pansexual | 0 (0%) | 39 | 3 (3.9%) | 77 |

| Prefer not to specify | 1 (3%) | 39 | 2 (2.6%) | 77 |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||

| African American/Black | 6 (15%) | 39 | 14 (18.2%) | 77 |

| Asian | 10 (26%) | 39 | 13 (16.9%) | 77 |

| Latino/a | 3 (8%) | 39 | 6 (7.8%) | 77 |

| White/Caucasian | 13 (33%) | 39 | 32 (41.6%) | 77 |

| American Indian | 0 (0%) | 39 | 1 (1.3%) | 77 |

| Polynesian | 1 (3%) | 39 | 0 (0%) | 77 |

| Multiracial | 5 (13%) | 39 | 10 (13%) | 77 |

| Middle Eastern | 0 (0%) | 39 | 1 (1.3%) | 77 |

| Black Caribbean | 1 (3%) | 39 | 0 (0%) | 77 |

| Employment | ||||

| Yes | 16 (41%) | 39 | 32 (41.6%) | 77 |

| No | 23 (59%) | 39 | 45 (58.4%) | 77 |

| Household income | ||||

| Above 200,000 USD | 6 (15%) | 39 | 15 (19.5%) | 77 |

| 100,000–200,000 USD | 8 (21%) | 39 | 11 (14.3%) | 77 |

| 75,000–100,000 USD | 9 (23%) | 39 | 14 (18.2%) | 77 |

| 50,000–75,000 USD | 5 (13%) | 39 | 9 (11.7%) | 77 |

| 30,000–50,000 USD | 5 (13%) | 39 | 13 (16.9%) | 77 |

| 15,000–30,000 USD | 5 (13%) | 39 | 8 (10.4%) | 77 |

| other/not applicable | 1 (3%) | 39 | 4 (5.2%) | 77 |

| International status | ||||

| Yes | 5 (13%) | 39 | 17 (22.1%) | 77 |

| No | 34 (87%) | 39 | 60 (77.9%) | 77 |

| Clinical Characteristics | ||||

| Elevated depression a | 17 (44%) | 39 | 27 (35.1%) | 77 |

| Elevated anxiety b | 18 (46%) | 39 | 29 (37.7%) | 77 |

| Elevated post-traumatic stress c | 29 (74%) | 39 | 57 (74%) | 77 |

| Spiritual Characteristics | ||||

| Religious affiliation | ||||

| Buddhist | 0 (0%) | 39 | 1 (1.3%) | 77 |

| Hindu | 2 (5%) | 39 | 1 (1.3%) | 77 |

| Eastern Orthodox | 0 (0%) | 39 | 2 (2.6%) | 77 |

| Jewish | 6 (15%) | 39 | 4 (5.2%) | 77 |

| Muslim | 2 (5%) | 39 | 2 (2.6%) | 77 |

| Protestant Christian | 5 (13%) | 39 | 9 (11.7%) | 77 |

| Roman Catholic | 3 (8%) | 39 | 9 (11.7%) | 77 |

| Other | 4 (10%) | 39 | 10 (13%) | 77 |

| None | 17 (44%) | 39 | 39 (50.6%) | 77 |

| Importance of religion or spirituality | ||||

| Highly Important | 11 (28%) | 39 | 13 (16.9%) | 77 |

| Moderately Important | 14 (36%) | 39 | 24 (31.2%) | 77 |

| Slightly Important | 12 (31%) | 39 | 22 (28.6%) | 77 |

| Not Important at All | 2 (5%) | 39 | 18 (23.4%) | 77 |

| Importance of religion | ||||

| Highly Important | 6 (15%) | 39 | 3 (11.1%) | 27 |

| Moderately Important | 5 (13%) | 39 | 6 (22.2%) | 27 |

| Slightly Important | 14 (36%) | 39 | 4 (14.8%) | 27 |

| Not Important at All | 14 (36%) | 39 | 14 (51.9%) | 27 |

| Importance of spirituality | ||||

| Highly Important | 10 (26%) | 39 | 8 (29.6%) | 27 |

| Moderately Important | 15 (39%) | 39 | 9 (33.3%) | 27 |

| Slightly Important | 14 (36%) | 39 | 5 (18.5%) | 27 |

| Not Important at All | 0 (0%) | 39 | 5 (18.5%) | 27 |

| M (SD) | /n | M (SD) | /n | |

| Age | 20.4 (1.52) | 39 | 19.5 (1.5) | 77 |

| n | Rate (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Attended required pre-group orientation session | 67 | -- |

| Enrolled a | 60 | 90% |

| Completed pretest and post-test measures (retention) b | 42 | 70% |

| Attended ≥ 1 session | 54 | -- |

| Attended ≥ 4 sessions (engagement) c | 37 | 69% |

| Attended ≥ 1 session and completed post-test measures (AA-A group) d | 39 | -- |

Third Iteration: Affordances and Constraints Across Themes

|

| Second Iteration: Pattern Variables 1A. Access to the community during COVID-19 1B. Access to community for people otherwise isolated (outside COVID) 1C. Peer relationships restricted without face-to-face interaction 2A. Increased access for commuters, people with disabilities, people who are socially anxious 2B. Support to spiritual journeys prompted by COVID-19 2C. Access to mental health resources during COVID-19 stress 2D. Decreased loneliness during COVID-19 isolation 3A. Harder to focus online 3B. Internet issues 3C. Bluelight/screen time 3D. Zoom platform did not get in the way of AA-A feeling distinct from a class 3E. Zoom breakout rooms 3F. Camera on/off |

| First Iteration: Initial Codes 1A. Affordance: access to community during COVID-19 1C. Constraint: relationships restricted without face-to-face interaction 2A. Affordance: increased access for those with pain or disability 2A. Affordance: reduces feelings of social anxiety 2A. Affordance: population for whom AA online might be suited 2A. Affordance: more comfort/access 2B. Affordance: support to spiritual journey during COVID-19 2C. Affordance: access to meditation during COVID-19 isolation 2C. Affordance: access to mental health resources during COVID-19 stress 2D. Affordance: decreased loneliness 3A. Constraint: home environment associated with work 3A. Constraint: harder to focus online 3A. Affordance: easier to focus during meditation online with the camera off 3B. Constraint: internet issues 3C. Constraint: blue light/screen time 3D. Affordance: felt distinct from a class although on the same online platform (Zoom) 3E. Affordance: increased vulnerability 3E. Affordance: Zoom breakout rooms 3E. Constraint: Zoom breakout rooms can be awkward 3F. Affordance: privacy during meditation 3F. Affordance: camera on/off 3F. Constraint: camera on/off |

| T1 | T2 | Paired Difference (T2 − T1) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical well-being | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | 95% CI | t (df) | p (one-tailed) | Cohen’s d |

| Depression symptoms a | 8.87 (5.62) | 7.54 (5.21) | −1.33 (5.57) | −3.14, 0.47 | −1.49 (38) | 0.072 | −0.24 |

| Anxiety symptoms b | 9.46 (6.14) | 7.41 (5.69) | −2.05 (5.96) | −3.98, −0.12 | −2.15 (38) | 0.019 ** | −0.34 |

| Post-traumatic stress c | 41.79 (13.57) | 37.51 (11.93) | −4.28 (10.44) | −7.67, −0.90 | −2.56 (38) | 0.007 ** | −0.41 |

| Spiritual well-being | |||||||

| Awakened awareness d | 32.74 (6.55) | 34.79 (7.37) | 2.05 (5.51) | 0.26, 3.84 | 2.32 (38) | 0.013 ** | 0.37 |

| Spirituality e | 100.51 (16.46) | 104.79 (18.56) | 4.28 (12.26) | 0.31, 8.26 | 2.18 (38) | 0.018 ** | 0.35 |

| Spiritual growth f | 114.13 (39.56) | 118.38 (45.23) | 4.26 (36.01) | −7.42, 15.93 | 0.74 (38) | 0.233 | 0.12 |

| Spiritual decline f | 35.59 (12.74) | 24.49 (11.15) | −11.1 (12.1) | −15.03, −7.18 | −5.73 (38) | <0.001 ** | −0.92 |

| Dependent Variable | Predictor | df | Mean Square | F | η2 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression symptoms a | (Intercept) | 1 | 137.44 | 5.71 | 0.049 | 0.019 * |

| SGM status | 1 | 139.90 | 5.81 | 0.049 | 0.018 * | |

| Delivery method | 1 | 0.58 | 0.004 | 0.000 | 0.961 | |

| SGM status × delivery method | 1 | 170.34 | 7.08 | 0.059 | 0.009 ** | |

| Error | 112 | 24.06 | ||||

| Anxiety symptoms b | (Intercept) | 1 | 285.87 | 10.00 | 0.082 | 0.002 ** |

| SGM status | 1 | 40.60 | 1.42 | 0.013 | 0.236 | |

| Delivery method | 1 | 4.13 | 0.14 | 0.001 | 0.705 | |

| SGM status × delivery method | 1 | 235.87 | 8.25 | 0.069 | 0.005 ** | |

| Error | 112 | 28.58 | ||||

| Post-traumatic stress c | (Intercept) | 1 | 2373.59 | 22.71 | 0.169 | <0.001 ** |

| SGM status | 1 | 58.10 | 0.56 | 0.005 | 0.457 | |

| Delivery method | 1 | 49.76 | 0.48 | 0.004 | 0.492 | |

| SGM status × delivery method | 1 | 100.81 | 0.97 | 0.009 | 0.328 | |

| Error | 112 | 104.50 | ||||

| Awakened Awareness d | (Intercept) | 1 | 768.71 | 26.12 | 0.239 | <0.001 ** |

| SGM status | 1 | 183.00 | 6.22 | 0.070 | 0.015 * | |

| Delivery method | 1 | 116.89 | 3.97 | 0.046 | 0.050 * | |

| SGM status × delivery method | 1 | 99.57 | 3.38 | 0.039 | 0.069 | |

| Error | 83 | 29.44 | ||||

| Spirituality e | (Intercept) | 1 | 4655.86 | 21.44 | 0.161 | <0.001 ** |

| SGM status | 1 | 487.45 | 2.25 | 0.020 | 0.137 | |

| Delivery method | 1 | 834.12 | 3.84 | 0.033 | 0.052 | |

| SGM status × delivery method | 1 | 657.79 | 3.03 | 0.026 | 0.085 | |

| Error | 112 | 217.13 | ||||

| Spiritual Growth f | (Intercept) | 1 | 3405.36 | 1.93 | 0.017 | 0.167 |

| SGM status | 1 | 3491.41 | 1.99 | 0.017 | 0.162 | |

| Delivery method | 1 | 762.58 | 0.43 | 0.004 | 0.512 | |

| SGM status × delivery method | 1 | 9456.83 | 5.37 | 0.046 | 0.022 * | |

| Error | 112 | 1761.59 | ||||

| Spiritual Decline f | (Intercept) | 1 | 10,433.45 | 50.98 | 0.313 | <0.001 ** |

| SGM status | 1 | 145.58 | 0.71 | 0.006 | 0.401 | |

| Delivery method | 1 | 57.47 | 0.28 | 0.003 | 0.597 | |

| SGM status × delivery method | 1 | 136.83 | 0.67 | 0.006 | 0.415 | |

| Error | 112 | 204.65 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mistur, E.J.; Crete, A.A.; Scalora, S.C.; Anderson, M.R.; Chapman, A.L.; Miller, L. Awakened Awareness Online: Results from an Open Trial of a Spiritual–Mind–Body Wellness Intervention for Remote Undergraduate Students. Psychol. Int. 2025, 7, 32. https://doi.org/10.3390/psycholint7020032

Mistur EJ, Crete AA, Scalora SC, Anderson MR, Chapman AL, Miller L. Awakened Awareness Online: Results from an Open Trial of a Spiritual–Mind–Body Wellness Intervention for Remote Undergraduate Students. Psychology International. 2025; 7(2):32. https://doi.org/10.3390/psycholint7020032

Chicago/Turabian StyleMistur, Elisabeth J., Abigail A. Crete, Suza C. Scalora, Micheline R. Anderson, Amy L. Chapman, and Lisa Miller. 2025. "Awakened Awareness Online: Results from an Open Trial of a Spiritual–Mind–Body Wellness Intervention for Remote Undergraduate Students" Psychology International 7, no. 2: 32. https://doi.org/10.3390/psycholint7020032

APA StyleMistur, E. J., Crete, A. A., Scalora, S. C., Anderson, M. R., Chapman, A. L., & Miller, L. (2025). Awakened Awareness Online: Results from an Open Trial of a Spiritual–Mind–Body Wellness Intervention for Remote Undergraduate Students. Psychology International, 7(2), 32. https://doi.org/10.3390/psycholint7020032