Assessment of Human Health Risks from Exposure to Lubricating Eye Drops Used in the Treatment of Dry Eye Disease

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection, Acid Digestion, Calibration Curves, and Elemental Analysis

2.2. Risk Assessment

2.2.1. Non-Carcinogenic Risk

2.2.2. Carcinogenic Risk

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

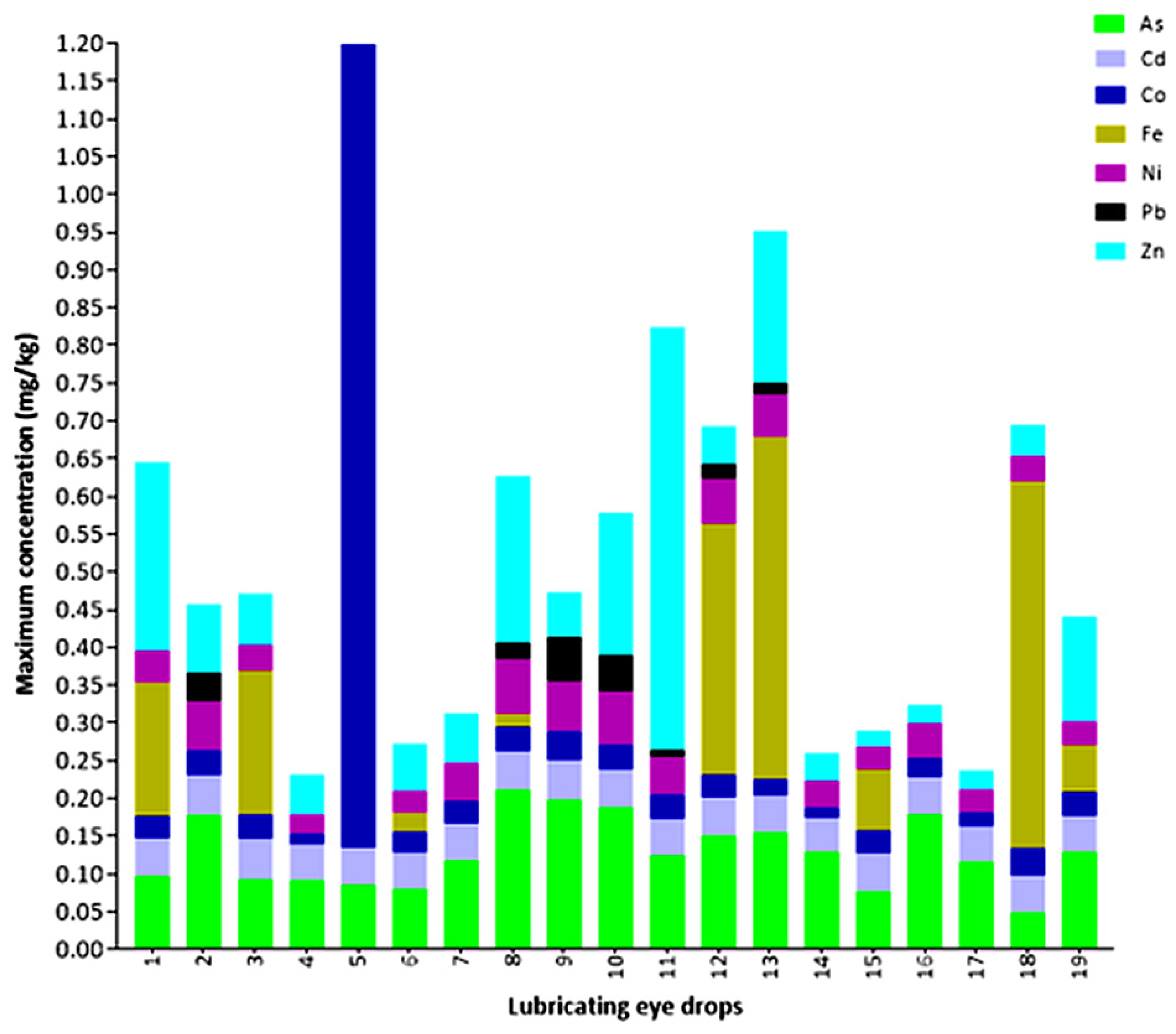

3.1. Maximum Concentration of Elements in Lubricating Eye Drops

3.2. Average Daily Dose

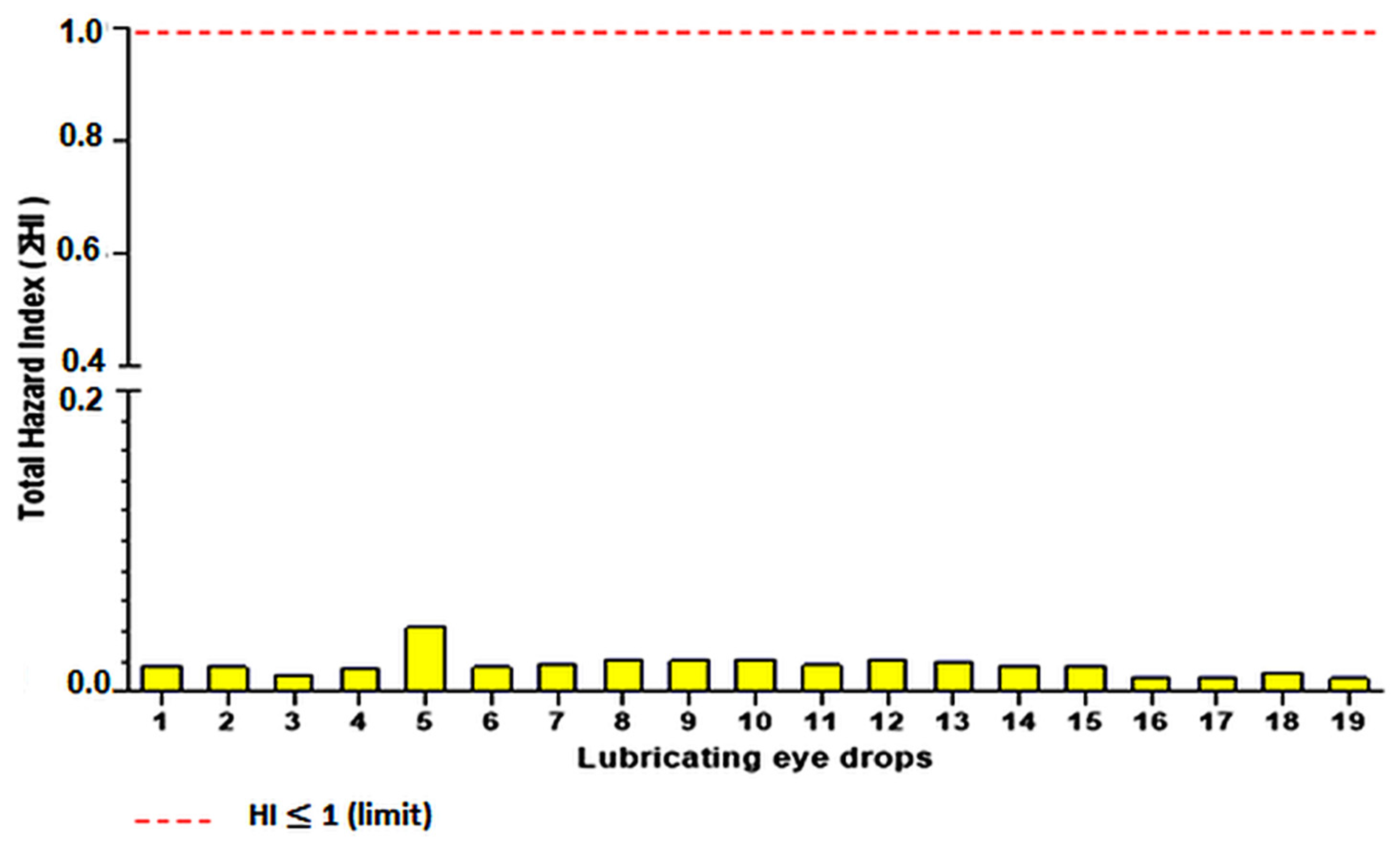

3.3. Non-Carcinogenic Risk

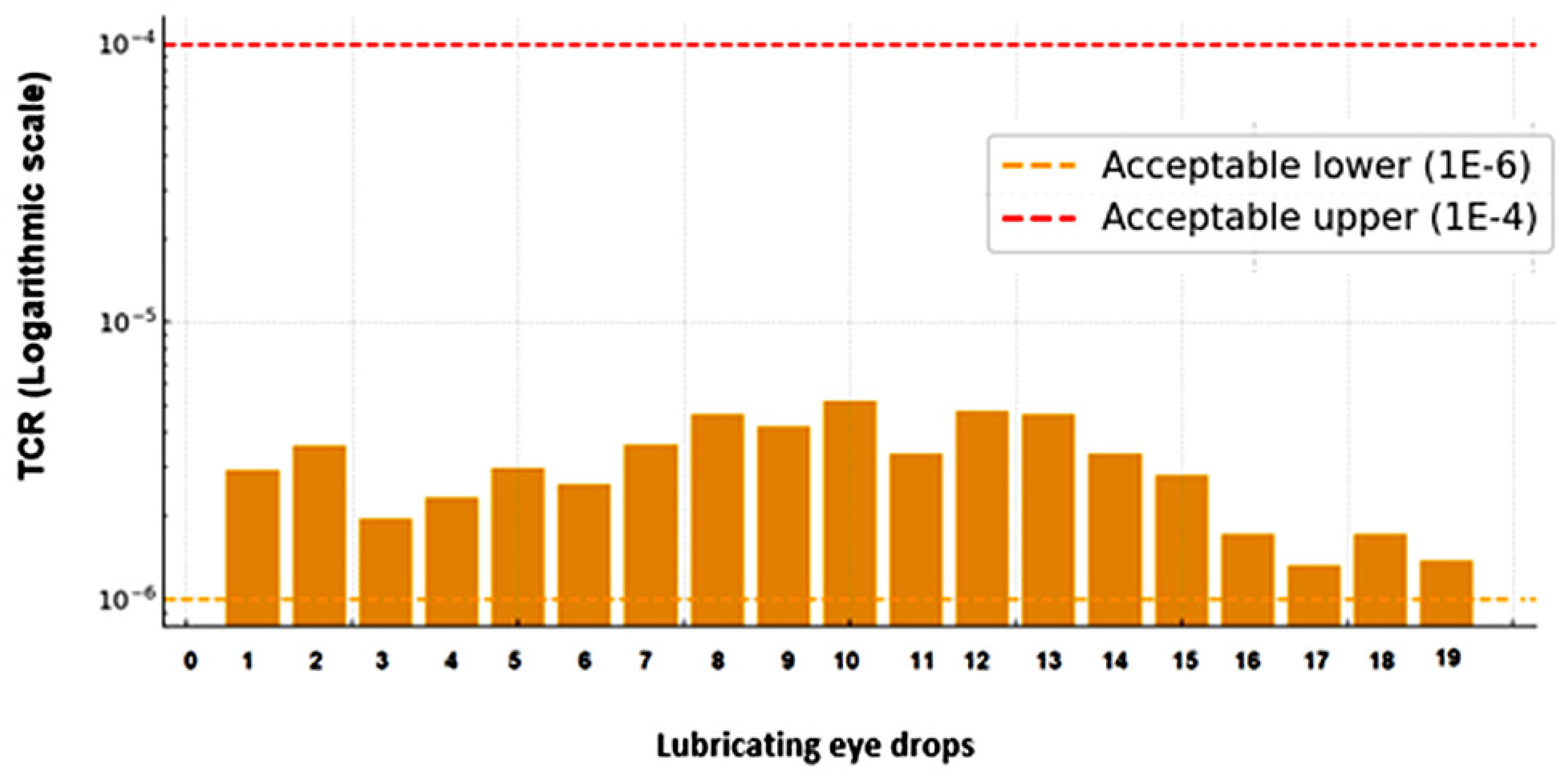

3.4. Carcinogenic Risk

4. Discussion

4.1. Maximum Quantified Concentration in Lubricating Eye Drops

4.2. Average Daily Dose

4.3. Non-Carcinogenic Risk

4.4. Carcinogenic Risk

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shaw, M. How to administer eye drops and ointments. Nurs. Times 2014, 16–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaves, C. Ocular Senescence and the 21st Century. Rev. Bras. Oftalmol. 2010, 69, 215–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golden, M.I.; Meyer, J.J.; Patel, B.C. Dry Eye Syndrome; StatPearls Publishing: Tampa, FL, USA; St. Petersburg, FL, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Şimşek, C.; Doğru, M.; Kojima, T.; Tsubota, K. Current Management and Treatment of Dry Eye Disease. Turk. J. Ophthalmol. 2018, 48, 309–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchino, M.; Uchino, Y.; Dogru, M.; Kawashima, M.; Yokoi, N.; Komuro, A.; Sonomura, Y.; Kato, H.; Kinoshita, S.; Schaumberg, D.A.; et al. Dry Eye Disease and Work Productivity Loss in Visual Display Users: The Osaka Study. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2014, 157, 294–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Gong, L.; Chapin, W.J.; Zhu, M. Assessment of Vision-Related Quality of Life in Dry Eye Patients. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2012, 53, 5722–5727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosa, A. Discover Everything About Dry Eye Syndrome. RetinaPro. Available online: https://retinapro.com.br/blog/doenca-ocular/descubra-tudo-sobre-a-sindrome-do-olho-seco/ (accessed on 28 April 2025).

- Dogru, M.; Nakamura, M.; Shimazaki, J.; Tsubota, K. Changing Trends in the Treatment of Dry-Eye Disease. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs 2013, 22, 1581–1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fonseca, E.C.; Arruda, G.V.; Rocha, E.M. Dry eye: Etiopathogenesis and treatment. Arq. Bras. Oftalmol. 2010, 73, 197–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prinz, J.; Maffulli, N.; Fuest, M.; Walter, P.; Hildebrand, F.; Migliorini, F. Placebo Administration for Dry Eye Disease: A Level I Evidence Based Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 2022, 44, 1087–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, M.; Melo, E.S.P.; Silva, T.C.; Cardozo, C.M.L.; Siqueira, I.V.; Hamaji, M.P.; Braga, V.T.; Martin, L.F.T.; Fonseca, A.; Nascimento, V.A. Quantification of Metal (Loid)s in Lubricating Eye Drops Used in the Treatment of Dry Eye Disease. Molecules 2023, 28, 6508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, R.F.T. Range and Output Simulation for Elemental Impurities in Drug Products. Master’s Thesis, University of Lisbon, Lisbon, Portugal, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Alam, M.F.; Akhter, M.; Mazumder, B.; Ferdous, A.; Hossain, M.D.; Dafader, N.C.; Ahmed, F.T.; Kundu, S.K.; Taheri, T.; Atique Ullah, A.K.M. Assessment of Some Heavy Metals in Selected Cosmetics Commonly Used in Bangladesh and Human Health Risk. J. Anal. Sci. Technol. 2019, 10, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalili, F.; Mahvi, A.H.; Nasseri, S.; Yunesian, M.; Yaseri, M.; Djahed, B. Health Risk Assessment of Dermal Exposure to Heavy Metals Content of Chemical Hair Dyes. Iran. J. Public Health 2019, 48, 902–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shomar, B.; Rashkeev, S.N. A Comprehensive Risk Assessment of Toxic Elements in International Brands of Face Foundation Powders. Environ. Res. 2021, 192, 110274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Järvinen, K.; Järvinen, T.; Urtti, A. Ocular Absorption Following Topical Delivery. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 1995, 16, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrahari, V.; Mandal, A.; Agrahari, V.; Trinh, H.M.; Joseph, M.; Ray, A.; Hadji, H.; Mitra, R.; Pal, D.; Mitra, A.K. A Comprehensive Insight on Ocular Pharmacokinetics. Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 2016, 6, 735–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Amo, E.M. Topical Ophthalmic Administration: Can a Drug Instilled onto the Ocular Surface Exert an Effect at the Back of the Eye? Front. Drug Deliv. 2022, 2, 954771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachu, R.D.; Chowdhury, P.; Al-Saedi, Z.H.F.; Karla, P.K.; Boddu, S.H.S. Ocular Drug Delivery Barriers—Role of Nanocarriers in the Treatment of Anterior Segment Ocular Diseases. Pharmaceutics 2018, 10, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Amo, E.M.; Urtti, A. Current and Future Ophthalmic Drug Delivery Systems: A Shift to the Posterior Segment. Drug Discov. Today 2008, 13, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Osman, M.; Yang, F.; Massey, I.Y. Exposure Routes and Health Effects of Heavy Metals on Children. Biometals 2019, 32, 563–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayenimo, J.G.; Yusuf, A.M.; Adekunle, A.S.; Makinde, O.W. Heavy Metal Exposure from Personal Care Products. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2010, 84, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, M.F.D.J. Assessment of Health Risks Resulting from Mixtures of Metals Potentially Present in Medicines. Master’s Thesis, Higher Institute of Health Sciences Egas Moniz, Almada, Portugal, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Aberami, S.; Nikhalashree, S.; Bharathselvi, M.; Biswas, J.; Sulochana, K.N.; Coral, K. Elemental Concentrations in Choroid-RPE and Retina of Human Eyes with Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Exp. Eye Res. 2019, 186, 107718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocca, B.; Forte, G.; Pisano, A.; Farace, C.; Giancipoli, E.; Pinna, A.; Dore, S.; Madeddu, R. A Pilot Study to Evaluate the Levels of Aqueous Humor Trace Elements in Open-Angle Glaucoma. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2020, 61, 126560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Chen, Y.; Lai, C. Clinical Association between Trace Elements of Tear and Dry Eye Metrics. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 18052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, M.R.; Ju, M.J.; Kim, D.H.; Choi, Y. Comparison of Environmental Phthalates and Heavy Metals Exposures by Dry Eye Disease Status. Fall 2020 Online Conference. In Proceedings of the Online Conference of the Korean Society for Environmental Health and Toxicology, in Virtual, 13 November 2020; p. 142. [Google Scholar]

- Dolar-Szczasny, J.; Święch, A.; Flieger, J.; Tatarczak-Michalewska, M.; Niedzielski, P.; Proch, J.; Majerek, D.; Kawka, J.; Mackiewicz, J. Levels of Trace Elements in the Aqueous Humor of Cataract Patients Measured by the Inductively Coupled Plasma Optical Emission Spectrometry. Molecules 2019, 24, 4127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BRASIL. Brazilian Pharmacopoeia, 7th ed.; Brazilian Health Regulatory Agency: Brasilia, Brazil, 2024; Volume I—RDC n 940/2024.

- ICH. Guideline for Elemental Impurities Q3D (R2); The International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- USEPA Risk Assessment Guidance for Superfund. Volume I: Human Health Evaluation Manual (Part A), Interim Final; U.S. Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 1989.

- Long, G.L.; Winefordner, J.D. Limit of Detection. A Closer Look at the IUPAC Definition. Available online: https://pubs.acs.org/doi/pdf/10.1021/ac00258a001 (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Scientific, T.F. Thermo Scientific Tech Tip; Thermo Fisher Scientific: Waltham, MA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, M.; Ellison, S.L.R.; Wood, R. Harmonized Guidelines for Single-Laboratory Validation of Methods of Analysis: (IUPAC Technical Report). Pure Appl. Chem. 2002, 74, 167–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsay, E.; del Amo, E.M.; Toropainen, E.; Tengvall-Unadike, U.; Ranta, V.-P.; Urtti, A.; Ruponen, M. Corneal and Conjunctival Drug Permeability: Systematic Comparison and Pharmacokinetic Impact in the Eye. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2018, 119, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batistuzzo, J.; Filho, A.L. Formulações Magistrais Em Oftalmologia. Acta Farm. Port. 2011, 1, 65–76. [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal, P.; Craig, J.P.; Rupenthal, I.D. Formulation Considerations for the Management of Dry Eye Disease. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farkouh, A.; Frigo, P.; Czejka, M. Systemic Side Effects of Eye Drops: A Pharmacokinetic Perspective. Clin. Ophthalmol. 2016, 10, 2433–2441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paulsen, F.P.; Föge, M.; Thale, A.B.; Tillmann, B.N.; Mentlein, R. Animal Model for the Absorption of Lipophilic Substances from Tear Fluid by the Epithelium of the Nasolacrimal Ducts. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2002, 43, 3137–3143. [Google Scholar]

- Rothe, H.; Fautz, R.; Gerber, E.; Neumann, L.; Rettinger, K.; Schuh, W.; Gronewold, C. Special Aspects of Cosmetic Spray Safety Evaluations: Principles on Inhalation Risk Assessment. Toxicol. Lett. 2011, 205, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EPA/100/B-19/001; USEPA Guidelines for Human Exposure Assessment. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 2019.

- Lux, A.; Maier, S.; Dinslage, S.; Süverkrüp, R.; Diestelhorst, M. A Comparative Bioavailability Study of Three Conventional Eye Drops versus a Single Lyophilisate. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2003, 87, 436–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamad, S.H.; Schauer, J.J.; Shafer, M.M.; Al-Rheem, E.A.; Skaar, P.S.; Heo, J.; Tejedor-Tejedor, I. Risk Assessment of Total and Bioavailable Potentially Toxic Elements (PTEs) in Urban Soils of Baghdad–Iraq. Sci. Total Environ. 2014, 494, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sah, D.; Verma, P.K.; Kumari, K.M.; Lakhani, A. Chemical Partitioning of Fine Particle-Bound As, Cd, Cr, Ni, Co, Pb and Assessment of Associated Cancer Risk Due to Inhalation, Ingestion and Dermal Exposure. Inhal. Toxicol. 2017, 29, 483–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saha, N.; Rahman, M.S.; Ahmed, M.B.; Zhou, J.L.; Ngo, H.H.; Guo, W. Industrial Metal Pollution in Water and Probabilistic Assessment of Human Health Risk. J. Environ. Manag. 2017, 185, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Victor, O.; Kingsley Chukwuemeka, P.-I.; Eucharia, N. Heavy Metals Contents and Health Risk Assessment of Classroom Corner Dusts in Selected Public Primary Schools in Rivers State, Nigeria. J. Environ. Pollut. Hum. Health 2018, 6, 138–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Sousa, C.I.P. Characterization of Tear Film Parameters and Corneal Topography in the Portuguese Adult Population: A Pilot Study. Master’s Thesis, University of Minho, Braga, Portugal, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ramsay, E.; Ruponen, M.; Picardat, T.; Tengvall, U.; Tuomainen, M.; Auriola, S.; Toropainen, E.; Urtti, A.; del Amo, E.M. Impact of Chemical Structure on Conjunctival Drug Permeability: Adopting Porcine Conjunctiva and Cassette Dosing for Construction of In Silico Model. J. Pharm. Sci. 2017, 106, 2463–2471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, W.; Gallagher, D.L.; Gohlke, J.M.; Dietrich, A.M. Children and Adults Are Exposed to Dual Risks from Ingestion of Water and Inhalation of Ultrasonic Humidifier Particles from Pb-Containing Water. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 791, 148248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DEP. Characterization of Risks Due to Inhalation of Particulates by Construction Workers; Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection: Worcester, MA, USA, 2008.

- Yan, L.; Franco, A.-M.; Elio, P. Health Risk Assessment via Ingestion and Inhalation of Soil PTE of an Urban Area. Chemosphere 2021, 281, 130964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goudarzi, G.; Alavi, N.; Geravandi, S.; Idani, E.; Behrooz, H.R.A.; Babaei, A.A.; Alamdari, F.A.; Dobaradaran, S.; Farhadi, M.; Mohammadi, M.J. Health Risk Assessment on Human Exposed to Heavy Metals in the Ambient Air PM10 in Ahvaz, Southwest Iran. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2018, 62, 1075–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBGE—Country’s Population Will Stop Growing in 2041. News Agency. Available online: https://agenciadenoticias.ibge.gov.br/agencia-noticias/2012-agencia-de-noticias/noticias/41056-populacao-do-pais-vai-parar-de-crescer-em-2041 (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- Aghlmand, R.; Rasi Nezami, S.; Abbasi, A. Evaluation of Chemical Parameters of Urban Drinking Water Quality along with Health Risk Assessment: A Case Study of Ardabil Province, Iran. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Han, J.; Wei, Y.; Li, G.; Sun, Y. Potential Ecological Risk and Health Risk Assessment of Heavy Metals and Metalloid in Soil around Xunyang Mining Areas. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USEPA. Methods for Derivation of Inhalation Reference Concentrations and Application of Inhalation Dosimetry; U.S. Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 1994.

- USEPA. Supplemental Guidance for Developing Soil Screening Levels for Superfund Sites; U.S. Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 2002.

- USEPA. Regional Screening Levels (RSLs)—Generic Tables; U.S. Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 2024.

- Mohammad, N.; Muhammad, N.; Nisar, M. Geo-Chemical Investigation and Health Risk Assessment of Potential Toxic Elements in Industrial Wastewater Irrigated Soil: A Geo-Statistical Approach. J. Biodivers. Environ. Sci. 2018, 12, 367–380. [Google Scholar]

- Adimalla, N. Heavy Metals Contamination in Urban Surface Soils of Medak Province, India, and Its Risk Assessment and Spatial Distribution. Environ. Geochem. Health 2020, 42, 59–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, P.; Guo, J.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, W.; Liu, L.; Liu, Y.; Lin, K. PM2.5, PM10 and Health Risk Assessment of Heavy Metals in a Typical Printed Circuit Noards Manufacturing Workshop. J. Environ. Sci. 2014, 26, 2018–2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aendo, P.; Netvichian, R.; Thiendedsakul, P.; Khaodhiar, S.; Tulayakul, P. Carcinogenic Risk of Pb, Cd, Ni, and Cr and Critical Ecological Risk of Cd and Cu in Soil and Groundwater around the Municipal Solid Waste Open Dump in Central Thailand. J. Environ. Public Health 2022, 2022, 3062215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammadi, A.A.; Zarei, A.; Majidi, S.; Ghaderpoury, A.; Hashempour, Y.; Saghi, M.H.; Alinejad, A.; Yousefi, M.; Hosseingholizadeh, N.; Ghaderpoori, M. Carcinogenic and Non-Carcinogenic Health Risk Assessment of Heavy Metals in Drinking Water of Khorramabad, Iran. MethodsX 2019, 6, 1642–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- USDOE. The Risk Assessment Information System; US Department of Energy’s Oak Ridge Operations Office (ORO): Oak Ridge, TN, USA, 2024.

- Ni, F.; Liu, G.; Ren, H.; Yang, S.; Ye, J.; Lu, X.; Yang, M. Health Risk Assessment on Rural Drinking Water Safety—A Case Study in Rain City District of Ya’an City of Sichuan Province. J. Water Resour. Prot. 2009, 1, 128–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Environmental Affairs. The Framework for the Management of Contaminated Land; Department of Environmental Affairs: Pretoria, South Africa, 2010.

- OEHHA, Appendix B. Chemical-Specific Summaries of the Information Used to Derive Unit Risk and Cancer Potency Values; California Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment: Sacramento, CA, USA, 2011; p. 626.

- OEHHA. Nickel and Nickel Compounds; California Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment: Sacramento, CA, USA, 2009.

- Johnbull, O.; Abbassi, B.; Zytner, R.G. Risk Assessment of Heavy Metals in Soil Based on the Geographic Information System-Kriging Technique in Anka, Nigeria. Environ. Eng. Res. 2019, 24, 150–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Mao, Z.; Huang, K.; Wang, X.; Cheng, L.; Zeng, L.; Zhou, Y.; Jing, T. Multiple Exposure Pathways and Health Risk Assessment of Heavy Metal (Loid)s for Children Living in Fourth-Tier Cities in Hubei Province. Environ. Int. 2019, 129, 517–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hohberger, B.; Chaudhri, M.A.; Michalke, B.; Lucio, M.; Nowomiejska, K.; Schlötzer-Schrehardt, U.; Grieb, P.; Rejdak, R.; Jünemann, A.G.M. Levels of Aqueous Humor Trace Elements in Patients with Open-Angle Glaucoma. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2018, 45, 150–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baidya, K.; Raj, A.; Mondal, L.; Bhaduri, G.; Todani, A. Persistent Conjunctivitis Associated with Drinking Arsenic-Contaminated Water. J. Ocul. Pharmacol. Ther. 2006, 22, 208–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallum, A.V. Involvement of the Cornea in Arsenic Poisoning: Report of a Case. Jama Ophthalmol. 1934, 12, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freund, P.; Al-Shafai, L.; Mankovskii, G.; Howarth, D.; Margolin, E. Clinicopathological Correlates: Chronic Arsenic Toxicity Causing Bilateral Symmetric Progressive Optic Neuropathy. J. Neuroophthalmol. 2020, 40, 423–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genchi, G.; Sinicropi, M.S.; Lauria, G.; Carocci, A.; Catalano, A.; Genchi, G.; Sinicropi, M.S.; Lauria, G.; Carocci, A.; Catalano, A. The Effects of Cadmium Toxicity. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erie, J.C.; Butz, J.A.; Good, J.A.; Erie, E.A.; Burritt, M.F.; Cameron, J.D. Heavy Metal Concentrations in Human Eyes. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2005, 139, 888–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amry, M.A.; Al-Saikhan, F.; Ayoubi, A. Toxic Effect of Cadmium Found in Eyeliner to the Eye of a 21 Year Old Saudi Woman: A Case Report. Saudi Pharm. J. 2011, 19, 269–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, M.D.; Hur, M.; Chen, J.J.; Bhatti, M.T. Cobalt Toxic Optic Neuropathy and Retinopathy: Case Report and Review of the Literature. Am. J. Ophthalmol. Case Rep. 2020, 17, 100606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, C.A.; Khan, J.; Chelva, E.; Khan, R.; Unsworth-Smith, T. The Effect of Cobalt on the Human Eye. Doc. Ophthalmol. 2015, 130, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obied, B.; Richard, S.; Zahavi, A.; Kreizman-Shefer, H.; Bajar, J.; Fixler, D.; Krmpotić, M.; Girshevitz, O.; Goldenberg-Cohen, N. Cobalt Toxicity Induces Retinopathy and Optic Neuropathy in Mice. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2024, 65, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, R.W.; Richa, D.C.; Hahn, P.; Green, W.R.; Dunaief, J.L. Iron Toxicity as a Potential Factor in AMD. RETINA 2007, 27, 997–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erol, M.A.; Ozalp, O.; Atalay, E. Cataract secondary to iatrogenic iron overload in a severely anemic patient. Indian J. Ophthalmol.-Case Rep. 2021, 1, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asproudis, I.; Zafeiropoulos, P.; Katsanos, A.; Kolettis, C. Severe Self-Inflicted Acute Ocular Siderosis Caused by an Iron Tablet in the Conjunctival Fornix. Acta Medica 2017, 60, 160–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hołyńska-Iwan, I.; Sobiesiak, M.; Kowalczyk, W.; Wróblewski, M.; Cwynar, A.; Szewczyk-Golec, K. Nickel Ions Influence the Transepithelial Sodium Transport in the Trachea, Intestine and Skin. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 6931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.-N.; Liu, H.; Liu, M.-M.; Yang, D.-L.; Bi, J.; Chen, Q.-Q.; Chen, W.; Xiang, P.; Zhang, Z.-N.; Liu, H.; et al. Effects of Nickel at Environmentally Relevant Concentrations on Human Corneal Epithelial Cells: Oxidative Damage and Cellular Apoptosis. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cekic, O. Effect of Cigarette Smoking on Copper, Lead, and Cadmium Accumulation in Human Lens. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 1998, 82, 186–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liou, Y.; Chen, Y.; Chen, W.; Li, K.; Chou, T.; Huang, Y.; Wang, C.; Lai, C. Associations between Biomarkers of Metal Exposure and Dry Eye Metrics in Shipyard Welders: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hore, P. Lead Poisoning in a Mother and Her Four Children Using a Traditional Eye Cosmetic—New York City, 2012–2023. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2024, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nourmohammadi, I.; Modarress, M.; Pakdel, F. Assessment of Aqueous Humor Zinc Status in Human Age-Related Cataract. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2006, 50, 51–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nriagu, J.O. (Ed.) Arsenic in the Environment: Advances in Environmental: Cycling and Characterization; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H.; Park, K. In Vitro Cytotoxicity of Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles in Cultured Statens Seruminstitut Rabbit Cornea Cells. Toxicol. Res. 2019, 35, 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amartey, E.O.; Asumadu-Sakyi, A.B.; Adjei, C.A.; Quashie, F.K.; Duodu, G.O.; Bentil, N.O. Determination of Heavy Metals Concentration in Hair Pomades on the Ghanaian Market Using Atomic Absorption Spectrometry Technique. Br. J. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2011, 2, 192–198. [Google Scholar]

- Ezeabara, C.; Ogochukwu, O.; Emeka, A.; Okeke, C.; Mbaekwe, E. Heavy Metal Contamination of Herbal Drugs: Implication for Human Health-A Review. Int. J. Trop. Dis. Health 2014, 4, 1044–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, P.K.; Lee, S.S.; Zhang, M.; Tsang, Y.F.; Kim, K.-H. Heavy Metals in Food Crops: Health Risks, Fate, Mechanisms, and Management. Environ. Int. 2019, 125, 365–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Element | External Calibration Equation (y = ax + b) | LOD (µg/g) | LOQ (µg/g) | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| As | y = 449.70x + 1.31 | 0.0040 | 0.01333 | 0.9997 |

| Cd | y = 14390x − 47.20 | 0.0006 | 0.00200 | 0.9995 |

| Co | y = 5676x − 0.30 | 0.0019 | 0.00633 | 0.9996 |

| Fe | y = 10380x + 18.40 | 0.0070 | 0.02333 | 0.9993 |

| Ni | y = 5121x − 4.00 | 0.0016 | 0.00533 | 0.9997 |

| Pb | y = 996x + 9.60 | 0.0060 | 0.02000 | 0.9991 |

| Zn | y = 10719x − 37.30 | 0.0019 | 0.00633 | 0.9990 |

| Element | Spike (%) |

|---|---|

| As | 91.20 |

| Cd | 96.02 |

| Co | 91.15 |

| Fe | 96.20 |

| Ni | 93.12 |

| Pb | 96.23 |

| Zn | 99.20 |

| Parameters | Values |

|---|---|

| RF power | 1250 W |

| Wash pump rate | 0.45 L/min |

| Plasma gas flow rate | 12 L/min |

| Integration time | 5 s |

| Stabilization time | 20 s |

| Nebulizer pressure | 20 psi |

| Plasma view | axial |

| Analytes/wavelength (nm) | As (189.042) |

| Cd (228.802) | |

| Co (228.616) | |

| Fe (259.940) | |

| Ni (221.647) | |

| Pb (220.353) | |

| Zn (213.856) |

| Eye Drop Identification | Maximum Daily Frequency | Maximum Daily Eye Dose (mL/day) | Exposure Time (h/day) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5 * | 0.454 | 0.5 |

| 2 | 4 | 0.408 | 0.4 |

| 3 | 3 | 0.306 | 0.3 |

| 4 | 5 | 0.400 | 0.5 |

| 5 | 5 | 0.510 | 0.5 |

| 6 | 5 * | 0.454 | 0.5 |

| 7 | 5 * | 0.526 | 0.5 |

| 8 | 5 * | 0.490 | 0.5 |

| 9 | 5 * | 0.454 | 0.5 |

| 10 | 5 * | 0.589 | 0.5 |

| 11 | 5 * | 0.480 | 0.5 |

| 12 | 5 * | 0.610 | 0.5 |

| 13 | 5 * | 0.600 | 0.5 |

| 14 | 5 * | 0.510 | 0.5 |

| 15 | 5 * | 0.490 | 0.5 |

| 16 | 3 | 0.200 | 0.3 |

| 17 | 3 | 0.200 | 0.3 |

| 18 | 4 | 0.333 | 0.4 |

| 19 | 3 | 0.200 | 0.3 |

| Parameters | Unit | Value | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maximum concentration of elements (C) | mg/kg | a | |

| Conjunctival contact area (Aconjunctiva) | cm2 | 8.5 b | [16] |

| Corneal contact area (Acornea) | cm2 | 1 | [16,47] |

| Mean permeability coefficient of the conjunctiva (Kpconjunctiva) | cm/h | 2.05 × 10−2 | Adapted from Ramsay et al. (2017) [48] |

| Mean corneal permeability coefficient (Kpcornea) | cm/h | 8.62 × 10−3 | Adapted from Ramsay et al. (2018) [35] |

| Exposure time (ET) | h/day | c | |

| Exposure frequency (EF) | day/year | 365 | |

| Exhibition duration (ED) | Year | 36.4 d | |

| Body weight (BW) | kg | 70 kg | [49] |

| Average time (AT) | Day | 13286 | (EF × ED) |

| Inhalation rate (InhR) | m3/day | 20 | [49,50,51] |

| Particle emission factor (PEF) | m3/kg | 1.36 × 109 | [51,52] |

| Ingestion rate (IngR) | mL/day | e | |

| Conversion factor (CF) | kg → g (dermal) L → cm3 (oral) | 1.00 × 10−3 |

| Element | RfDOral (mg/kg.day) | RfC (mg/m3) | RfDinhalation (mg/kg.day) | ABSGI | RfDdermal (mg/kg.dia) *** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| As | 3.00 × 10−4 | 1.50 × 10−5 | 4.29 × 10−6 ** | 1 | 3.00 × 10−4 |

| Cd | 1.00 × 10−4 | 1.00 × 10−5 | 2.86 × 10−6 ** | 5.00 × 10−2 | 5.00 × 10−6 |

| Co | 3.00 × 10−4 | 6.00 × 10−6 | 1.71 × 10−6 ** | 1 | 3.00 × 10−4 |

| Fe | 7.00 × 10−1 | - | 2.20 × 10−4 a | 1 | 7.00 × 10−1 |

| Ni | 2.00 × 10−2 | 1.00 × 10−5 | 2.86 × 10−6 ** | 4.00 × 10−2 | 8.00 × 10−4 |

| Pb | 1.40 × 10−3 b | 3.52 × 10−3 c | 1.01 × 10−3 ** | 1 | 1.40 × 10−3 |

| Zn | 3.00 × 10−1 | 3.00 × 10−1 c | 8.57 × 10−2 ** | 1 | 3.00 × 10−1 |

| Element | CSFOral | CSFInhalation | CSFDermal * |

|---|---|---|---|

| As | 1.50 × 100 a | 1.50 × 101 c | 1.50 × 100 |

| Cd | 6.10 × 100 b | 6.30 × 100 c | 3.05 × 10−1 |

| Ni | 1.70 × 100 f | 9.10 × 10−1 e | 6.80 × 10−2 |

| Pb | 8.50 × 10−3 a | 4.20 × 10−2 d | 8.50 × 10−3 |

| Element | Mean of Maximum Concentrations (mg/kg) | Standard Deviation | Coefficient of Variation | Lowest Maximum Concentration Value (mg/kg) | Highest Maximum Concentration Value (mg/kg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| As | 0.12945 | 0.04628 | 35.75% | 0.0495 | 0.2120 |

| Cd | 0.04901 | 0.00223 | 4.55% | 0.0447 | 0.0532 |

| Co | 0.08515 | 0.24702 | 290.11% | 0.0138 | 1.1048 |

| Fe | 0.09583 | 0.15894 | 165.86% | 0.0000 * | 0.4851 |

| Ni | 0.04520 | 0.01579 | 34.94% | 0.0255 | 0.0729 |

| Pb | 0.01120 | 0.01848 | 165.09% | 0.0000 * | 0.0595 |

| Zn | 0.11540 | 0.12958 | 112.29% | 0.0208 | 0.5598 |

| Lubricating Eye Drops/Element | As (mg/kg) * | Cd (mg/kg) * | Co (mg/kg) * | Fe (mg/kg) * | Ni (mg/kg) * | Pb (mg/kg) * | Zn (mg/kg) * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.0974 b | 0.0499 a | 0.0300 b | 0.1762 b | 0.0429 bc | <LOD | 0.2492 b |

| 2 | 0.1781 a | 0.0525 a | 0.0334 b | <LOD | 0.0647 a | 0.0380 a | 0.0903 c |

| 3 | 0.0933 b | 0.0532 a | 0.0325 b | 0.1905 b | 0.0340 cd | <LOD | 0.0682 c |

| 4 | 0.0923 b | 0.0464 a | 0.0147 b | <LOD | 0.0255 d | <LOD | 0.0530 c |

| 5 | 0.0858 b | 0.0487 a | 1.1048 a | <LOD | 0.0286 d | <LOD | 0.0384 c |

| 6 | 0.0804 b | 0.0482 a | 0.0274 b | 0.0248 c | 0.0294 d | <LOD | 0.0624 c |

| 7 | 0.1185 b | 0.0483 a | 0.0301 b | <LOD | 0.0503 bc | <LOD | 0.0662 c |

| 8 | 0.2120 a | 0.0502 a | 0.0328 b | 0.0170 c | 0.0729 a | 0.0220 ab | 0.2201 b |

| 9 | 0.1985 a | 0.0522 a | 0.0383 b | <LOD | 0.0659 a | 0.0595 a | 0.0591 c |

| 10 | 0.1887 a | 0.0502 a | 0.0324 b | <LOD | 0.0702 a | 0.0485 a | 0.1884 b |

| 11 | 0.1255 b | 0.0470 a | 0.0329 b | <LOD | 0.0493 bc | 0.0101 ab | 0.5598 a |

| 12 | 0.1513 ab | 0.0505 a | 0.0300 b | 0.3320 b | 0.0599 ab | 0.0193 ab | 0.0499 c |

| 13 | 0.1553 ab | 0.0488 a | 0.0216 b | 0.4529 a | 0.0565 ab | 0.0153 ab | 0.2013 b |

| 14 | 0.1296 b | 0.0447 a | 0.0138 b | <LOD | 0.0357 cd | <LOD | 0.0362 c |

| 15 | 0.0775 b | 0.0498 a | 0.0307 b | 0.0808 c | 0.0299 d | <LOD | 0.0208 c |

| 16 | 0.1797 a | 0.0492 a | 0.0243 b | <LOD | 0.0472 bc | <LOD | 0.0237 c |

| 17 | 0.1166 b | 0.0465 a | 0.0184 b | <LOD | 0.0305 d | <LOD | 0.0254 c |

| 18 | 0.0495 c | 0.0482 a | 0.0371 b | 0.4851 a | 0.0336 cd | <LOD | 0.0412 c |

| 19 | 0.1296 b | 0.0467 a | 0.0326 b | 0.0615 c | 0.0318 cd | <LOD | 0.1389 bc |

| Lubricating Eye Drops/Element | As (mg/kg) | Cd (mg/kg) | Co (mg/kg) | Fe (mg/kg) | Ni (mg/kg) | Pb (mg/kg) | Zn (mg/kg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.0974 | 0.0499 | 0.0300 | 0.1762 | 0.0429 | <LOD | 0.2492 |

| 2 | 0.1781 | 0.0525 | 0.0334 | <LOD | 0.0647 | 0.0380 | 0.0903 |

| 3 | 0.0933 | 0.0532 | 0.0325 | 0.1905 | 0.0340 | <LOD | 0.0682 |

| 4 | 0.0923 | 0.0464 | 0.0147 | <LOD | 0.0255 | <LOD | 0.0530 |

| 5 | 0.0858 | 0.0487 | 1.1048 | <LOD | 0.0286 | <LOD | 0.0384 |

| 6 | 0.0804 | 0.0482 | 0.0274 | 0.0248 | 0.0294 | <LOD | 0.0624 |

| 7 | 0.1185 | 0.0483 | 0.0301 | <LOD | 0.0503 | <LOD | 0.0662 |

| 8 | 0.2120 | 0.0502 | 0.0328 | 0.0170 | 0.0729 | 0.0220 | 0.2201 |

| 9 | 0.1985 | 0.0522 | 0.0383 | <LOD | 0.0659 | 0.0595 | 0.0591 |

| 10 | 0.1887 | 0.0502 | 0.0324 | <LOD | 0.0702 | 0.0485 | 0.1884 |

| 11 | 0.1255 | 0.0470 | 0.0329 | <LOD | 0.0493 | 0.0101 | 0.5598 |

| 12 | 0.1513 | 0.0505 | 0.0300 | 0.3320 | 0.0599 | 0.0193 | 0.0499 |

| 13 | 0.1553 | 0.0488 | 0.0216 | 0.4529 | 0.0565 | 0.0153 | 0.2013 |

| 14 | 0.1296 | 0.0447 | 0.0138 | <LOD | 0.0357 | <LOD | 0.0362 |

| 15 | 0.0775 | 0.0498 | 0.0307 | 0.0808 | 0.0299 | <LOD | 0.0208 |

| 16 | 0.1797 | 0.0492 | 0.0243 | <LOD | 0.0472 | <LOD | 0.0237 |

| 17 | 0.1166 | 0.0465 | 0.0184 | <LOD | 0.0305 | <LOD | 0.0254 |

| 18 | 0.0495 | 0.0482 | 0.0371 | 0.4851 | 0.0336 | <LOD | 0.0412 |

| 19 | 0.1296 | 0.0467 | 0.0326 | 0.0615 | 0.0318 | <LOD | 0.1389 |

| Brazilian Pharmacopoeia | 0.1500 | 0.0500 | NA | NA | 2.5000 | 0.1000 | NA |

| ICH Q3D (R2) | 1.5000 | 0.2000 | 0.5000 | NA | 2.0000 | 0.5000 | NA |

| Lubricating Eye Drops | Route of Exposure | As | Cd | Co | Fe | Ni | Pb | Zn |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Dermal | 1.27 × 10−7 | 6.51 × 10−8 | 3.92 × 10−8 | 2.30 × 10−7 | 5.60 × 10−8 | 3.25 × 10−7 | |

| Inhalation | 2.05 × 10−11 | 1.05 × 10−11 | 6.30 × 10−12 | 3.70 × 10−11 | 9.01 × 10−12 | 5.24 × 10−11 | ||

| Oral | 5.05 × 10−7 | 2.59 × 10−7 | 1.56 × 10−7 | 9.14 × 10−7 | 2.23 × 10−7 | 1.29 × 10−6 | ||

| 2 | Dermal | 1.86 × 10−7 | 5.48 × 10−8 | 3.49 × 10−8 | 6.76 × 10−8 | 3.97 × 10−8 | 9.43 × 10−8 | |

| Inhalation | 3.74 × 10−11 | 1.10 × 10−11 | 7.02 × 10−12 | 1.36 × 10−11 | 7.98 × 10−12 | 1.90 × 10−11 | ||

| Oral | 8.30 × 10−7 | 2.45 × 10−7 | 1.56 × 10−7 | 3.02 × 10−7 | 1.77 × 10−7 | 4.21 × 10−7 | ||

| 3 | Dermal | 7.31 × 10−8 | 4.17 × 10−8 | 2.55 × 10−8 | 1.49 × 10−7 | 2.66 × 10−8 | 5.34 × 10−8 | |

| Inhalation | 1.96 × 10−11 | 1.12 × 10−11 | 6.83 × 10−12 | 4.00 × 10−11 | 7.14 × 10−12 | 1.43 × 10−11 | ||

| Oral | 3.26 × 10−7 | 1.86 × 10−7 | 1.14 × 10−7 | 6.66 × 10−7 | 1.19 × 10−7 | 2.39 × 10−7 | ||

| 4 | Dermal | 1.20 × 10−7 | 6.06 × 10−8 | 1.92 × 10−8 | 3.33 × 10−8 | 6.92 × 10−8 | ||

| Inhalation | 1.94 × 10−11 | 9.75 × 10−12 | 3.09 × 10−12 | 5.36 × 10−12 | 1.11 × 10−11 | |||

| Oral | 4.22 × 10−7 | 2.12 × 10−7 | 6.72 × 10−8 | 1.17 × 10−7 | 2.42 × 10−7 | |||

| 5 | Dermal | 1.12 × 10−7 | 6.36 × 10−8 | 1.44 × 10−6 | 3.73 × 10−8 | 5.01 × 10−8 | ||

| Inhalation | 1.80 × 10−11 | 1.02 × 10−11 | 2.32 × 10−10 | 6.01 × 10−12 | 8.07 × 10−12 | |||

| Oral | 5.00 × 10−7 | 2.84 × 10−7 | 6.44 × 10−6 | 1.67 × 10−7 | 2.24 × 10−7 | |||

| 6 | Dermal | 1.05 × 10−7 | 6.29 × 10−8 | 3.58 × 10−8 | 3.24 × 10−8 | 3.84 × 10−8 | 8.14 × 10−8 | |

| Inhalation | 1.69 × 10−11 | 1.01 × 10−11 | 5.76 × 10−12 | 5.21 × 10−12 | 6.18 × 10−12 | 1.31 × 10−11 | ||

| Oral | 4.17 × 10−7 | 2.50 × 10−7 | 1.42 × 10−7 | 1.29 × 10−7 | 1.53 × 10−7 | 3.24 × 10−7 | ||

| 7 | Dermal | 1.55 × 10−7 | 6.30 × 10−8 | 3.93 × 10−8 | 6.57 × 10−8 | 8.64 × 10−8 | ||

| Inhalation | 2.49 × 10−11 | 1.01 × 10−11 | 6.32 × 10−12 | 1.06 × 10−11 | 1.39 × 10−11 | |||

| Oral | 7.12 × 10−7 | 2.90 × 10−7 | 1.81 × 10−7 | 3.02 × 10−7 | 3.98 × 10−7 | |||

| 8 | Dermal | 2.77 × 10−7 | 6.55 × 10−8 | 4.28 × 10−8 | 2.22 × 10−8 | 9.52 × 10−8 | 2.87 × 10−8 | 2.87 × 10−7 |

| Inhalation | 4.45 × 10−11 | 1.05 × 10−11 | 6.89 × 10−12 | 3.57 × 10−12 | 1.53 × 10−11 | 4.62 × 10−12 | 4.62 × 10−11 | |

| Oral | 1.19 × 10−6 | 2.81 × 10−7 | 1.84 × 10−7 | 9.52 × 10−8 | 4.08 × 10−7 | 1.23 × 10−7 | 1.23 × 10−6 | |

| 9 | Dermal | 2.59 × 10−7 | 6.81 × 10−8 | 5.00 × 10−8 | 8.60 × 10−8 | 7.77 × 10−8 | 7.71 × 10−8 | |

| Inhalation | 4.17 × 10−11 | 1.10 × 10−11 | 8.05 × 10−12 | 1.38 × 10−11 | 1.25 × 10−11 | 1.24 × 10−11 | ||

| Oral | 1.03 × 10−6 | 2.71 × 10−7 | 1.99 × 10−7 | 3.42 × 10−7 | 3.09 × 10−7 | 3.07 × 10−7 | ||

| 10 | Dermal | 2.46 × 10−7 | 6.55 × 10−8 | 4.23 × 10−8 | 9.16 × 10−8 | 6.33 × 10−8 | 2.46 × 10−7 | |

| Inhalation | 3.96 × 10−11 | 1.05 × 10−11 | 6.81 × 10−12 | 1.47 × 10−11 | 1.02 × 10−11 | 3.96 × 10−11 | ||

| Oral | 1.27 × 10−6 | 3.38 × 10−7 | 2.18 × 10−7 | 4.73 × 10−7 | 3.26 × 10−7 | 1.27 × 10−6 | ||

| 11 | Dermal | 1.64 × 10−7 | 6.13 × 10−8 | 4.29 × 10−8 | 6.43 × 10−8 | 1.32 × 10−8 | 7.31 × 10−7 | |

| Inhalation | 2.64 × 10−11 | 9.87 × 10−12 | 6.91 × 10−12 | 1.04 × 10−11 | 2.12 × 10−12 | 1.18 × 10−10 | ||

| Oral | 6.88 × 10−7 | 2.58 × 10−7 | 1.80 × 10−7 | 2.70 × 10−7 | 5.54 × 10−8 | 3.07 × 10−6 | ||

| 12 | Dermal | 1.97 × 10−7 | 6.59 × 10−08 | 3.92 × 10−8 | 4.33 × 10−7 | 7.82 × 10−8 | 2.52 × 10−8 | 6.51 × 10−8 |

| Inhalation | 3.18 × 10−11 | 1.06 × 10−11 | 6.30 × 10−12 | 6.97 × 10−11 | 1.26 × 10−11 | 4.05 × 10−12 | 1.05 × 10−11 | |

| Oral | 1.05 × 10−6 | 3.52 × 10−07 | 2.09 × 10−7 | 2.31 × 10−6 | 4.18 × 10−7 | 1.35 × 10−7 | 3.48 × 10−7 | |

| 13 | Dermal | 2.03 × 10−7 | 6.37 × 10−8 | 2.82 × 10−8 | 5.91 × 10−7 | 7.37 × 10−8 | 2.00 × 10−8 | 2.63 × 10−7 |

| Inhalation | 3.26 × 10−11 | 1.03 × 10−11 | 4.54 × 10−12 | 9.51 × 10−11 | 1.19 × 10−11 | 3.21 × 10−12 | 4.23 × 10−11 | |

| Oral | 1.06 × 10−6 | 3.35 × 10−7 | 1.48 × 10−7 | 3.11 × 10−6 | 3.87 × 10−7 | 1.05 × 10−7 | 1.38 × 10−6 | |

| 14 | Dermal | 1.69 × 10−7 | 5.83 × 10−8 | 1.80 × 10−8 | 4.66 × 10−8 | 4.73 × 10−8 | ||

| Inhalation | 2.72 × 10−11 | 9.39 × 10−12 | 2.90 × 10−12 | 7.50 × 10−12 | 7.61 × 10−12 | |||

| Oral | 7.55 × 10−7 | 2.61 × 10−7 | 8.04 × 10−8 | 2.08 × 10−7 | 2.11 × 10−7 | |||

| 15 | Dermal | 1.01 × 10−7 | 6.50 × 10−8 | 4.01 × 10−8 | 1.05 × 10−7 | 3.90 × 10−8 | 2.71 × 10−8 | |

| Inhalation | 1.63 × 10−11 | 1.05 × 10−11 | 6.45 × 10−12 | 1.70 × 10−11 | 6.28 × 10−12 | 4.37 × 10−12 | ||

| Oral | 4.34 × 10−7 | 2.79 × 10−7 | 1.72 × 10−7 | 4.52 × 10−7 | 1.67 × 10−7 | 1.16 × 10−7 | ||

| 16 | Dermal | 1.41 × 10−7 | 3.85 × 10−8 | 1.90 × 10−8 | 3.70 × 10−8 | 1.86 × 10−8 | ||

| Inhalation | 3.78 × 10−11 | 1.03 × 10−11 | 5.11 × 10−12 | 9.92 × 10−12 | 4.98 × 10−12 | |||

| Oral | 4.11 × 10−7 | 1.12 × 10−7 | 5.55 × 10−8 | 1.08 × 10−7 | 5.42 × 10−8 | |||

| 17 | Dermal | 9.13 × 10−8 | 3.64 × 10−8 | 1.44 × 10−8 | 2.39 × 10−8 | 1.99 × 10−8 | ||

| Inhalation | 2.45 × 10−11 | 9.77 × 10−12 | 3.87 × 10−12 | 6.41 × 10−12 | 5.34 × 10−12 | |||

| Oral | 2.67 × 10−7 | 1.06 × 10−7 | 4.21 × 10−8 | 6.97 × 10−8 | 5.81 × 10−8 | |||

| 18 | Dermal | 5.17 × 10−8 | 5.03 × 10−8 | 3.87 × 10−8 | 5.07 × 10−7 | 3.51 × 10−8 | 4.30 × 10−8 | |

| Inhalation | 1.04 × 10−11 | 1.01 × 10−11 | 7.79 × 10−12 | 1.02 × 10−10 | 7.06 × 10−12 | 8.66 × 10−12 | ||

| Oral | 1.88 × 10−7 | 1.83 × 10−7 | 1.41 × 10−7 | 1.85 × 10−6 | 1.28 × 10−7 | 1.57 × 10−7 | ||

| 19 | Dermal | 1.01 × 10−7 | 3.66 × 10−8 | 2.55 × 10−8 | 4.82 × 10−8 | 2.49 × 10−8 | 1.09 × 10−7 | |

| Inhalation | 2.72 × 10−11 | 9.81 × 10−12 | 6.85 × 10−12 | 1.29 × 10−11 | 6.68 × 10−12 | 2.92 × 10−11 | ||

| Oral | 2.96 × 10−7 | 1.07 × 10−7 | 7.45 × 10−8 | 1.41 × 10−7 | 7.27 × 10−8 | 3.17 × 10−7 |

| Lubricating Eye Drops | Route of Exposure | As | Cd | Co | Fe | Ni | Pb | Zn |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Dermal | 4.24 × 10−4 | 1.30 × 10−2 | 1.31 × 10−4 | 3.29 × 10−7 | 7.00 × 10−5 | 1.08 × 10−6 | |

| Inhalation | 4.77 × 10−6 | 3.67 × 10−6 | 3.69 × 10−6 | 1.68 × 10−7 | 3.15 × 10−6 | 6.11 × 10−10 | ||

| Oral | 1.68 × 10−3 | 2.59 × 10−3 | 5.19 × 10−4 | 1.31 × 10−6 | 1.11 × 10−5 | 4.31 × 10−6 | ||

| 2 | Dermal | 6.20 × 10−4 | 1.10 × 10−2 | 1.16 × 10−4 | 8.45 × 10−5 | 2.83 × 10−5 | 3.14 × 10−7 | |

| Inhalation | 8.72 × 10−6 | 3.86 × 10−6 | 4.10 × 10−6 | 4.75 × 10−6 | 7.90 × 10−9 | 2.21 × 10−10 | ||

| Oral | 2.77 × 10−3 | 2.45 × 10−3 | 5.19 × 10−4 | 1.51 × 10−5 | 1.27 × 10−4 | 1.40 × 10−6 | ||

| 3 | Dermal | 2.44 × 10−4 | 8.33 × 10−3 | 8.48 × 10−5 | 2.13 × 10−7 | 3.33 × 10−5 | 1.78 × 10−7 | |

| Inhalation | 4.57 × 10−6 | 3.91 × 10−6 | 3.99 × 10−6 | 1.82 × 10−7 | 2.50 × 10−6 | 1.67 × 10−10 | ||

| Oral | 1.09 × 10−3 | 1.86 × 10−3 | 3.79 × 10−4 | 9.52 × 10−7 | 5.95 × 10−6 | 7.95 × 10−7 | ||

| 4 | Dermal | 4.02 × 10−4 | 1.21 × 10−2 | 6.40 × 10−5 | 4.16 × 10−5 | 2.31 × 10−7 | ||

| Inhalation | 4.52 × 10−6 | 3.41 × 10−6 | 1.81 × 10−6 | 1.87 × 10−6 | 1.30 × 10−10 | |||

| Oral | 1.41 × 10−3 | 2.12 × 10−3 | 2.24 × 10−4 | 5.83 × 10−6 | 8.08 × 10−7 | |||

| 5 | Dermal | 3.73 × 10−4 | 1.27 × 10−2 | 4.81 × 10−3 | 4.67 × 10−5 | 1.67 × 10−7 | ||

| Inhalation | 4.20 × 10−6 | 3.58 × 10−6 | 1.36 × 10−4 | 2.10 × 10−6 | 9.41 × 10−11 | |||

| Oral | 1.67 × 10−3 | 2.84 × 10−3 | 2.15 × 10−2 | 8.33 × 10−6 | 7.46 × 10−7 | |||

| 6 | Dermal | 3.50 × 10−4 | 1.26 × 10−2 | 1.19 × 10−4 | 4.62 × 10−8 | 4.80 × 10−5 | 2.71 × 10−7 | |

| Inhalation | 3.94 × 10−6 | 3.54 × 10−6 | 3.37 × 10−6 | 2.37 × 10−8 | 2.16 × 10−6 | 1.53 × 10−10 | ||

| Oral | 1.39 × 10−3 | 2.50 × 10−3 | 4.74 × 10−4 | 1.84 × 10−7 | 7.63 × 10−6 | 1.08 × 10−6 | ||

| 7 | Dermal | 5.16 × 10−4 | 1.26 × 10−2 | 1.31 × 10−4 | 8.21 × 10−5 | 2.88 × 10−7 | ||

| Inhalation | 5.80 × 10−6 | 3.55 × 10−6 | 3.70 × 10−6 | 3.69 × 10−6 | 1.62 × 10−10 | |||

| Oral | 2.37 × 10−3 | 2.90 × 10−3 | 6.03 × 10−4 | 1.51 × 10−5 | 1.33 × 10−6 | |||

| 8 | Dermal | 9.22 × 10−4 | 1.31 × 10−2 | 1.43 × 10−4 | 3.17 × 10−8 | 1.19 × 10−4 | 2.05 × 10−5 | 9.58 × 10−7 |

| Inhalation | 1.04 × 10−5 | 3.69 × 10−6 | 4.03 × 10−6 | 1.62 × 10−8 | 5.35 × 10−6 | 4.58 × 10−9 | 5.40 × 10−10 | |

| Oral | 3.96 × 10−3 | 2.81 × 10−3 | 6.12 × 10−4 | 1.36 × 10−7 | 2.04 × 10−5 | 8.80 × 10−5 | 4.11 × 10−6 | |

| 9 | Dermal | 8.64 × 10−4 | 1.36 × 10−2 | 1.67 × 10−4 | 1.08 × 10−4 | 5.55 × 10−5 | 2.57 × 10−7 | |

| Inhalation | 9.72 × 10−6 | 3.83 × 10−6 | 4.71 × 10−6 | 4.84 × 10−6 | 1.24 × 10−8 | 1.45 × 10−10 | ||

| Oral | 3.43 × 10−3 | 2.71 × 10−3 | 6.62 × 10−4 | 1.71 × 10−5 | 2.21 × 10−4 | 1.02 × 10−6 | ||

| 10 | Dermal | 8.21 × 10−4 | 1.31 × 10−2 | 1.41 × 10−4 | 1.15 × 10−4 | 4.52 × 10−5 | 8.20 × 10−7 | |

| Inhalation | 9.24 × 10−6 | 3.69 × 10−6 | 3.98 × 10−6 | 5.16 × 10−6 | 1.01 × 10−8 | 4.62 × 10−10 | ||

| Oral | 4.23 × 10−3 | 3.38 × 10−3 | 7.27 × 10−4 | 2.36 × 10−5 | 2.33 × 10−4 | 4.23 × 10−6 | ||

| 11 | Dermal | 5.46 × 10−4 | 1.23 × 10−2 | 1.43 × 10−4 | 8.04 × 10−5 | 9.42 × 10−6 | 2.44 × 10−6 | |

| Inhalation | 6.15 × 10−6 | 3.45 × 10−6 | 4.04 × 10−6 | 3.62 × 10−6 | 2.10 × 10−9 | 1.37 × 10−9 | ||

| Oral | 2.29 × 10−3 | 2.58 × 10−3 | 6.02 × 10−4 | 1.35 × 10−5 | 3.96 × 10−5 | 1.02 × 10−5 | ||

| 12 | Dermal | 6.58 × 10−4 | 1.32 × 10−2 | 1.31 × 10−4 | 6.19 × 10−7 | 9.77 × 10−5 | 1.80 × 10−5 | 2.17 × 10−7 |

| Inhalation | 7.41 × 10−6 | 3.71 × 10−6 | 3.69 × 10−6 | 3.17 × 10−7 | 4.40 × 10−6 | 4.01 × 10−9 | 1.22 × 10−10 | |

| Oral | 3.52 × 10−3 | 3.52 × 10−3 | 6.97 × 10−4 | 3.31 × 10−6 | 2.09 × 10−5 | 9.61 × 10−5 | 1.16 × 10−6 | |

| 13 | Dermal | 6.76 × 10−4 | 1.27 × 10−2 | 9.40 × 10−5 | 8.45 × 10−7 | 9.22 × 10−5 | 1.43 × 10−5 | 8.76 × 10−7 |

| Inhalation | 7.61 × 10−6 | 3.58 × 10−6 | 2.65 × 10−6 | 4.32 × 10−7 | 4.15 × 10−6 | 3.18 × 10−9 | 4.93 × 10−10 | |

| Oral | 3.55 × 10−3 | 3.35 × 10−3 | 4.94 × 10−4 | 4.44 × 10−6 | 1.94 × 10−5 | 7.49 × 10−5 | 4.60 × 10−6 | |

| 14 | Dermal | 5.64 × 10−4 | 1.17 × 10−2 | 6.00 × 10−5 | 5.82 × 10−5 | 1.58 × 10−7 | ||

| Inhalation | 6.35 × 10−6 | 3.28 × 10−6 | 1.70 × 10−6 | 2.62 × 10−6 | 8.87 × 10−11 | |||

| Oral | 2.52 × 10−3 | 2.61 × 10−3 | 2.68 × 10−4 | 1.04 × 10−5 | 7.03 × 10−7 | |||

| 15 | Dermal | 3.37 × 10−4 | 1.30 × 10−2 | 1.34 × 10−4 | 1.51 × 10−7 | 4.88 × 10−5 | 9.05 × 10−8 | |

| Inhalation | 3.80 × 10−6 | 3.66 × 10−6 | 3.77 × 10−6 | 7.72 × 10−8 | 2.20 × 10−6 | 5.10 × 10−11 | ||

| Oral | 1.45 × 10−3 | 2.79 × 10−3 | 5.73 × 10−4 | 6.46 × 10−7 | 8.37 × 10−6 | 3.88 × 10−7 | ||

| 16 | Dermal | 4.69 × 10−4 | 7.71 × 10−3 | 6.34 × 10−5 | 4.62 × 10−5 | 6.19 × 10−8 | ||

| Inhalation | 8.80 × 10−6 | 3.61 × 10−6 | 2.99 × 10−6 | 3.47 × 10−6 | 5.81 × 10−11 | |||

| Oral | 1.37 × 10−3 | 1.12 × 10−3 | 1.85 × 10−4 | 5.39 × 10−6 | 1.81 × 10−7 | |||

| 17 | Dermal | 3.04 × 10−4 | 7.28 × 10−3 | 4.80 × 10−5 | 2.99 × 10−5 | 6.63 × 10−8 | ||

| Inhalation | 5.71 × 10−6 | 3.42 × 10−6 | 2.26 × 10−6 | 2.24 × 10−6 | 6.23 × 10−11 | |||

| Oral | 8.88 × 10−4 | 1.06 × 10−3 | 1.40 × 10−4 | 3.49 × 10−6 | 1.94 × 10−7 | |||

| 18 | Dermal | 1.72 × 10−4 | 1.01 × 10−2 | 1.29 × 10−4 | 7.24 × 10−7 | 4.39 × 10−5 | 1.43 × 10−7 | |

| Inhalation | 2.42 × 10−6 | 3.54 × 10−6 | 4.56 × 10−6 | 4.63 × 10−7 | 2.47 × 10−6 | 1.01 × 10−10 | ||

| Oral | 6.28 × 10−4 | 1.83 × 10−3 | 4.71 × 10−4 | 2.64 × 10−6 | 6.39 × 10−6 | 5.23 × 10−7 | ||

| 19 | Dermal | 3.38 × 10−4 | 7.31 × 10−3 | 8.51 × 10−5 | 6.88 × 10−8 | 3.11 × 10−5 | 3.63 × 10−7 | |

| Inhalation | 6.35 × 10−6 | 3.43 × 10−6 | 4.01 × 10−6 | 5.87 × 10−8 | 2.34 × 10−6 | 3.40 × 10−10 | ||

| Oral | 9.87 × 10−4 | 1.07 × 10−3 | 2.48 × 10−4 | 2.01 × 10−7 | 3.63 × 10−6 | 1.06 × 10−6 |

| Lubricating Eye Drops | As | Cd | Co | Fe | Ni | Pb | Zn | HI Total (∑HI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2.11 × 10−3 | 1.56 × 10−2 | 6.53 × 10−4 | 1.80 × 10−6 | 8.43 × 10−5 | 5.39 × 10−6 | 1.85 × 10−2 | |

| 2 | 3.40 × 10−3 | 1.34 × 10−2 | 6.39 × 10−4 | 1.04 × 10−4 | 1.55 × 10−4 | 1.72 × 10−6 | 1.77 × 10−2 | |

| 3 | 1.34 × 10−3 | 1.02 × 10−2 | 4.68 × 10−4 | 1.35 × 10−6 | 4.17 × 10−5 | 9.73 × 10−7 | 1.20 × 10−2 | |

| 4 | 1.81 × 10−3 | 1.42 × 10−2 | 2.90 × 10−4 | 4.93 × 10−5 | 1.04 × 10−6 | 1.64 × 10−2 | ||

| 5 | 2.04 × 10−3 | 1.56 × 10−2 | 2.64 × 10−2 | 5.71 × 10−5 | 9.13 × 10−7 | 4.41 × 10−2 | ||

| 6 | 1.74 × 10−3 | 1.51 × 10−2 | 5.96 × 10−4 | 2.54 × 10−7 | 5.78 × 10−5 | 1.35 × 10−6 | 1.75 × 10−2 | |

| 7 | 2.90 × 10−3 | 1.55 × 10−2 | 7.38 × 10−4 | 1.01 × 10−4 | 1.61 × 10−6 | 1.93 × 10−2 | ||

| 8 | 4.89 × 10−3 | 1.59 × 10−2 | 7.59 × 10−4 | 1.84 × 10−7 | 1.45 × 10−4 | 1.09 × 10−4 | 5.07 × 10−6 | 2.18 × 10−2 |

| 9 | 4.31 × 10−3 | 1.63 × 10−2 | 8.34 × 10−4 | 1.29 × 10−4 | 2.76 × 10−4 | 1.28 × 10−6 | 2.19 × 10−2 | |

| 10 | 5.06 × 10−3 | 1.65 × 10−2 | 8.72 × 10−4 | 1.43 × 10−4 | 2.78 × 10−4 | 5.05 × 10−6 | 2.29 × 10−2 | |

| 11 | 2.85 × 10−3 | 1.49 × 10−2 | 7.49 × 10−4 | 9.76 × 10−5 | 4.90 × 10−5 | 1.27 × 10−5 | 1.86 × 10−2 | |

| 12 | 4.18 × 10−3 | 1.67 × 10−2 | 8.31 × 10−4 | 4.24 × 10−6 | 1.23 × 10−4 | 1.14 × 10−4 | 1.38 × 10−6 | 2.20 × 10−2 |

| 13 | 4.23 × 10−3 | 1.61 × 10−2 | 5.90 × 10−4 | 5.71 × 10−6 | 1.16 × 10−4 | 8.92 × 10−5 | 5.48 × 10−6 | 2.11 × 10−2 |

| 14 | 3.09 × 10−3 | 1.43 × 10−2 | 3.30 × 10−4 | 7.13 × 10−5 | 8.61 × 10−7 | 1.78 × 10−2 | ||

| 15 | 1.79 × 10−3 | 1.58 × 10−2 | 7.10 × 10−4 | 8.74 × 10−7 | 5.94 × 10−5 | 4.79 × 10−7 | 1.84 × 10−2 | |

| 16 | 1.85 × 10−3 | 8.83 × 10−3 | 2.52 × 10−4 | 5.51 × 10−5 | 2.42 × 10−7 | 1.10 × 10−2 | ||

| 17 | 1.20 × 10−3 | 8.35 × 10−3 | 1.90 × 10−4 | 3.56 × 10−5 | 2.60 × 10−7 | 9.77 × 10−3 | ||

| 18 | 8.03 × 10−4 | 1.19 × 10−2 | 6.04 × 10−4 | 3.82 × 10−6 | 5.27 × 10−5 | 6.66 × 10−7 | 1.34 × 10−2 | |

| 19 | 1.33 × 10−3 | 8.39 × 10−3 | 3.37 × 10−4 | 3.28 × 10−7 | 3.71 × 10−5 | 1.42 × 10−6 | 1.01 × 10−2 |

| Lubricating Eye Drops | Route of Exposure | As | Cd | Ni | Pb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Dermal | 1.91 × 10−7 | 1.99 × 10−8 | 3.82 × 10−9 | |

| Inhalation | 3.07 × 10−10 | 6.60 × 10−11 | 8.22 × 10−12 | ||

| Oral | 7.58 × 10−7 | 1.58 × 10−6 | 3.79 × 10−7 | ||

| 2 | Dermal | 2.79 × 10−7 | 1.67 × 10−8 | 4.60 × 10−9 | 3.37 × 10−10 |

| Inhalation | 5.61 × 10−10 | 6.95 × 10−11 | 1.24 × 10−11 | 3.35 × 10−13 | |

| Oral | 1.25 × 10−6 | 1.49 × 10−6 | 5.14 × 10−7 | 1.51 × 10−09 | |

| 3 | Dermal | 1.10 × 10−7 | 1.27 × 10−8 | 1.81 × 10−9 | |

| Inhalation | 2.94 × 10−10 | 7.04 × 10−11 | 6.50 × 10−12 | ||

| Oral | 4.89 × 10−7 | 1.13 × 10−6 | 2.02 × 10−7 | ||

| 4 | Dermal | 1.81 × 10−7 | 1.85 × 10−8 | 2.26 × 10−9 | |

| Inhalation | 2.91 × 10−10 | 6.14 × 10−11 | 4.87 × 10−12 | ||

| Oral | 6.33 × 10−7 | 1.29 × 10−6 | 1.98 × 10−7 | ||

| 5 | Dermal | 1.68 × 10−7 | 1.94 × 10−8 | 2.54 × 10−9 | |

| Inhalation | 2.70 × 10−10 | 6.45 × 10−11 | 5.47 × 10−12 | ||

| Oral | 7.50 × 10−7 | 1.73 × 10−6 | 2.83 × 10−7 | ||

| 6 | Dermal | 1.57 × 10−7 | 1.92 × 10−8 | 2.61 × 10−9 | |

| Inhalation | 2.53 × 10−10 | 6.39 × 10−11 | 5.62 × 10−12 | ||

| Oral | 6.26 × 10−7 | 1.53 × 10−6 | 2.59 × 10−7 | ||

| 7 | Dermal | 2.32 × 10−7 | 1.93 × 10−8 | 4.47 × 10−9 | |

| Inhalation | 3.73 × 10−10 | 6.41 × 10−11 | 9.64 × 10−12 | ||

| Oral | 1.07 × 10−6 | 1.77 × 10−6 | 5.15 × 10−7 | ||

| 8 | Dermal | 4.15 × 10−7 | 2.00 × 10−8 | 6.47 × 10−9 | 2.44 × 10−10 |

| Inhalation | 6.68 × 10−10 | 6.64 × 10−11 | 1.39 × 10−11 | 1.94 × 10−13 | |

| Oral | 1.78 × 10−6 | 1.71 × 10−6 | 6.94 × 10−7 | 1.05 × 10−9 | |

| 9 | Dermal | 3.89 × 10−7 | 2.08 × 10−8 | 5.85 × 10−9 | 6.61 × 10−10 |

| Inhalation | 6.26 × 10−10 | 6.91 × 10−11 | 1.26 × 10−11 | 5.26 × 10−13 | |

| Oral | 1.54 × 10−6 | 1.65 × 10−6 | 5.81 × 10−7 | 2.63 × 10−9 | |

| 10 | Dermal | 3.69 × 10−7 | 2.00 × 10−8 | 6.24 × 10−9 | 5.38 × 10−10 |

| Inhalation | 5.95 × 10−10 | 6.64 × 10−11 | 1.34 × 10−11 | 4.28 × 10−13 | |

| Oral | 1.91 × 10−6 | 2.06 × 10−6 | 8.04 × 10−7 | 2.78 × 10−9 | |

| 11 | Dermal | 2.46 × 10−7 | 1.88 × 10−8 | 4.38 × 10−9 | 1.12 × 10−10 |

| Inhalation | 3.95 × 10−10 | 6.23 × 10−11 | 9.42 × 10−12 | 8.91 × 10−14 | |

| Oral | 1.03 × 10−6 | 1.58 × 10−6 | 4.60 × 10−7 | 4.71 × 10−10 | |

| 12 | Dermal | 2.96 × 10−7 | 2.01 × 10−8 | 5.32 × 10−9 | 2.14 × 10−10 |

| Inhalation | 4.76 × 10−10 | 6.68 × 10−11 | 1.15 × 10−11 | 1.70 × 10−13 | |

| Oral | 1.58 × 10−6 | 2.15 × 10−6 | 7.10 × 10−7 | 1.14 × 10−9 | |

| 13 | Dermal | 3.04 × 10−7 | 1.94 × 10−8 | 5.01 × 10−9 | 1.70 × 10−10 |

| Inhalation | 4.89 × 10−10 | 6.46 × 10−11 | 1.08 × 10−11 | 1.35 × 10−13 | |

| Oral | 1.60 × 10−6 | 2.04 × 10−6 | 6.59 × 10−7 | 8.92 × 10−10 | |

| 14 | Dermal | 2.54 × 10−7 | 1.78 × 10−8 | 3.17 × 10−9 | |

| Inhalation | 4.09 × 10−10 | 5.92 × 10−11 | 6.82 × 10−12 | ||

| Oral | 1.13 × 10−6 | 1.59 × 10−6 | 3.54 × 10−7 | ||

| 15 | Dermal | 1.52 × 10−7 | 1.98 × 10−8 | 2.65 × 10−9 | |

| Inhalation | 2.44 × 10−10 | 6.59 × 10−11 | 5.72 × 10−12 | ||

| Oral | 6.51 × 10−7 | 1.70 × 10−6 | 2.85 × 10−7 | ||

| 16 | Dermal | 2.11 × 10−7 | 1.18 × 10−8 | 2.51 × 10−9 | |

| Inhalation | 5.66 × 10−10 | 6.51 × 10−11 | 9.02 × 10−12 | ||

| Oral | 6.16 × 10−7 | 6.86 × 10−7 | 1.83 × 10−7 | ||

| 17 | Dermal | 1.37 × 10−7 | 1.11 × 10−8 | 1.63 × 10−9 | |

| Inhalation | 3.67 × 10−10 | 6.15 × 10−11 | 5.85 × 10−12 | ||

| Oral | 4.00 × 10−7 | 6.48 × 10−7 | 1.19 × 10−7 | ||

| 18 | Dermal | 7.75 × 10−8 | 1.53 × 10−8 | 2.39 × 10−9 | |

| Inhalation | 1.56 × 10−10 | 6.37 × 10−11 | 6.44 × 10−12 | ||

| Oral | 2.83 × 10−7 | 1.12 × 10−6 | 2.18 × 10−7 | ||

| 19 | Dermal | 1.52 × 10−7 | 1.12 × 10−8 | 1.69 × 10−9 | |

| Inhalation | 4.08 × 10−10 | 6.18 × 10−11 | 6.08 × 10−12 | ||

| Oral | 4.44 × 10−7 | 6.51 × 10−7 | 1.24 × 10−7 |

| Lubricating Eye Drops | As | Cd | Ni | Pb | TCR (∑RCTs) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 9.49 × 10−7 | 1.60 × 10−6 | 3.83 × 10−7 | 2.93 × 10−6 | |

| 2 | 1.53 × 10−6 | 1.51 × 10−6 | 5.18 × 10−7 | 1.84 × 10−9 | 3.56 × 10−6 |

| 3 | 5.99 × 10−7 | 1.15 × 10−6 | 2.04 × 10−7 | 1.95 × 10−6 | |

| 4 | 8.14 × 10−7 | 1.31 × 10−6 | 2.00 × 10−7 | 2.33 × 10−6 | |

| 5 | 9.18 × 10−7 | 1.75 × 10−6 | 2.86 × 10−7 | 2.96 × 10−6 | |

| 6 | 7.83 × 10−7 | 1.55 × 10−6 | 2.62 × 10−7 | 2.59 × 10−6 | |

| 7 | 1.30 × 10−6 | 1.79 × 10−6 | 5.20 × 10−7 | 3.61 × 10−6 | |

| 8 | 2.20 × 10−6 | 1.73 × 10−6 | 7.00 × 10−7 | 1.29 × 10−9 | 4.63 × 10−6 |

| 9 | 1.93 × 10−6 | 1.67 × 10−6 | 5.87 × 10−7 | 3.29 × 10−9 | 4.20 × 10−6 |

| 10 | 2.28 × 10−6 | 2.08 × 10−6 | 8.11 × 10−7 | 3.31 × 10−9 | 5.17 × 10−6 |

| 11 | 1.28 × 10−6 | 1.59 × 10−6 | 4.64 × 10−7 | 5.83 × 10−10 | 3.34 × 10−6 |

| 12 | 1.88 × 10−6 | 2.17 × 10−6 | 7.15 × 10−7 | 1.36 × 10−9 | 4.76 × 10−6 |

| 13 | 1.90 × 10−6 | 2.06 × 10−6 | 6.64 × 10−7 | 1.06 × 10−9 | 4.63 × 10−6 |

| 14 | 1.39 × 10−6 | 1.61 × 10−6 | 3.57 × 10−7 | 3.35 × 10−6 | |

| 15 | 8.03 × 10−7 | 1.72 × 10−6 | 2.87 × 10−7 | 2.81 × 10−6 | |

| 16 | 8.27 × 10−7 | 6.98 × 10−7 | 1.86 × 10−7 | 1.71 × 10−6 | |

| 17 | 5.37 × 10−7 | 6.60 × 10−7 | 1.21 × 10−7 | 1.32 × 10−6 | |

| 18 | 3.60 × 10−7 | 1.13 × 10−6 | 2.20 × 10−7 | 1.71 × 10−6 | |

| 19 | 5.97 × 10−7 | 6.62 × 10−7 | 1.25 × 10−7 | 1.38 × 10−6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

de Oliveira, M.; Melo, E.S.d.P.; Garcia, D.A.Z.; Braga, V.T.; Ancel, M.A.P.; Nascimento, V.A.d. Assessment of Human Health Risks from Exposure to Lubricating Eye Drops Used in the Treatment of Dry Eye Disease. J. Pharm. BioTech Ind. 2026, 3, 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpbi3010001

de Oliveira M, Melo ESdP, Garcia DAZ, Braga VT, Ancel MAP, Nascimento VAd. Assessment of Human Health Risks from Exposure to Lubricating Eye Drops Used in the Treatment of Dry Eye Disease. Journal of Pharmaceutical and BioTech Industry. 2026; 3(1):1. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpbi3010001

Chicago/Turabian Stylede Oliveira, Marcelo, Elaine S. de Pádua Melo, Diego Azevedo Zoccal Garcia, Vanessa Torres Braga, Marta Aratuza Pereira Ancel, and Valter Aragão do Nascimento. 2026. "Assessment of Human Health Risks from Exposure to Lubricating Eye Drops Used in the Treatment of Dry Eye Disease" Journal of Pharmaceutical and BioTech Industry 3, no. 1: 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpbi3010001

APA Stylede Oliveira, M., Melo, E. S. d. P., Garcia, D. A. Z., Braga, V. T., Ancel, M. A. P., & Nascimento, V. A. d. (2026). Assessment of Human Health Risks from Exposure to Lubricating Eye Drops Used in the Treatment of Dry Eye Disease. Journal of Pharmaceutical and BioTech Industry, 3(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpbi3010001