Abstract

Dog behavioural problems are one of the main reasons for dog relinquishment. Studies on how dog behavioural problems affect owner well-being are limited. We review the literature concerning the link between dog behavioural problems and owner well-being. We propose practical solutions to minimize the negative impacts of behavioural problems on human well-being and dog welfare, whilst suggesting future research directions. Twenty-one studies were included in the literature review. These indicate that dog behavioural problems may particularly reduce social interactions, and increase negative emotions of high arousal, such as stress and frustration, caregiver burden and symptoms of both depression and anxiety in their owners. To improve both owner well-being and dog welfare, we suggest targeting three areas: practical behavioural support for the dog–human dyad, social support for owners and psychological support for owners. Considering the lack of research in the field, further studies are needed to better understand the relationship between dog behavioural problems and human well-being, such as how the three areas previously mentioned may affect dog relinquishment and owner well-being.

1. Introduction

A dog behaviour problem is a behaviour shown by a dog that is perceived as problematic/annoying or dangerous by a human [1]. As such, this is a personal construct formed in the mind of an observer rather than an objectively definable entity [2]; it clearly relates to human well-being to some extent, but the point at which a behaviour becomes a problem is, by its nature, subjective. For example, behaviours such as aggression and predatory behaviour are serious concerns for owners and commonly described per se as a problem. By contrast, some behaviours such as vocalization and obedience problems are perceived as less serious and are more likely to be described as annoying habits by owners [3]. However, in this review, we will consider all dog responses that are perceived as of some concern by a human as behaviour problems, regardless of their severity or normalcy as part of the species behavioural repertoire In addition, for simplicity, the term ‘dog owner’ will be used throughout the manuscript, despite the preference of some for other terminologies, e.g., dog keeper, guardian, and pet parent.

It is widely recognized that owners of dogs perceived as more behaviourally problematic have greater intention to abandon their animal than other owners [4,5]; with dog behavioural problems (e.g., aggression, house soiling, destructive behaviour, and separation-related problems) being one of the most frequent reasons, if not the main reason, for relinquishment worldwide [6,7,8,9,10,11]. These issues can also lead to euthanasia [12] and are associated with poorer physical health and shortened lifespan in the dog [13,14].

Given the concomitant impact that these problems may have on human well-being and dog welfare, there is a surprising lack of studies which focus on the direct impact of behavioural problems on human well-being [15]. By contrast, there are many studies about the effects of human-related factors on dog emotions/behaviour, the impacts of behavioural problems on companion animal welfare, and the benefits of keeping pets [15,16]. Understanding the impact of problem dog behaviour is an essential prerequisite to the development of scientifically robust interventions to support these dog–owner dyads and, consequently, help improve their overall well-being.

Human well-being entails both hedonic and eudaimonic aspects. The former relates to an individual’s affective state (i.e., moods and emotions) and their satisfaction with their own life [17], while the latter refers to an individual’s functioning in life. This is commonly divided into six domains: autonomy (i.e., independence from the approval of others), self-acceptance (i.e., positive self-regard with acceptance of past life, bad and good characteristics), purpose in life (i.e., meaning in life and understanding of own purpose), personal growth (i.e., achievement of own potential), positive relations with others (i.e., good social relations and feelings of empathy and affection for others) and environmental mastery (i.e., effective management of own life and surrounding environment) [18]. Considering how pet ownership can compromise an owner’s hedonic and eudaimonic well-being, Kuntz et al. [19] describe caregiver burden as the multifaceted challenges perceived by an individual while providing care for their pet. Caregiver burden may ultimately be expressed in some form of mental illness, such as depression, anxiety or even suicidality [20,21,22]. Thus, studies about any of these aspects of owner well-being (hedonia, eudaimonia, caregiver burden and mental health problems) in relation to dog behavioural problems were the focus of this review. We aimed firstly to report the associations, identified in the scientific literature, between dog behavioural problems and dog owner well-being. Secondly, we propose practical interventions/strategies to ameliorate and prevent the negative impacts of behavioural problems on human well-being and dog welfare. Thirdly, we suggest future priority areas for research.

2. Selection of the Studies

The studies were populated from the first 150 results of two database searches in January 2024. All available date ranges were considered, and the following terms were used in the searches:

- Web of Science: dog* AND (“behavioural problem*” OR “behavioral problem*” OR “behaviour problem*” OR “behavior problem*”) AND (“owner*” OR “guardian*” OR “parent*” OR “caregiver*”) AND (“well-being” OR “wellbeing” OR “mental health” OR “welfare”),

- Google Scholar: dog, behavioural problems, owner, wellbeing.

In addition, the results were supplemented with the authors’ knowledge of the literature in the field of human–dog interactions.

To be included, the study had to be original, in English, and had to investigate or report an association between dog behavioural problems and owner well-being. Out of the 300 initial records obtained, 42 were retained after title and abstract screening. Subsequently, 21 were excluded for: not mentioning owner well-being (n = 17), not mentioning behavioural problems (n = 2), not involving dogs specifically (n = 1) or not being original research (n = 1). The remaining 21 were included in this review (see Supplementary Material Table S1).

3. Dog Behavioural Problems and Owner Emotions/Moods/Life Satisfaction

Associations between dog behavioural problems and hedonic well-being were found in 13 studies, (Table 1). All but one investigation (i.e., Barcelos et al.’s [23] cohort study) report a relationship between behavioural problems and negative emotions of high arousal in owners, such as stress, frustration and anger. Barcelos et al. [23] did not assess negative emotions of high arousal specifically, but hedonic well-being in general and loneliness. Owners whose dogs showed aggressive behaviour more frequently reported poorer hedonic well-being and higher loneliness scores; other behavioural problems were not associated with these well-being outcomes [23]. Several studies [15,24,25,26,27,28] also reported owners experiencing negative emotions of low arousal, such as sadness and fatigue/tiredness, due to dog behavioural problems. Thus, owners of dogs with behavioural problems are likely to frequently experience negative emotions of high and low arousal as a consequence of their dogs’ behavioural problems.

Although a large variety of behavioural problems were reported to be associated with negative emotions in owners (Table 1), some problems, such as aggression, appear to be more detrimental to hedonic well-being than others [23,25]. It also seems reasonable to suppose that the impact of a behavioural problem will vary with the owner’s own circumstances, such as their psychological state at the time, independent of any dog-specific issues. Indeed, in an early study in this field, O’Farrell [29] reported that problem behaviour causes greater distress to owners who are already anxious. In a study of autistic adults who owned dogs, sensory-related behaviours (e.g., barking) were commonly mentioned to affect their emotions negatively [26]. This aligns with the well-documented finding that heightened levels of anxiety are often observed in autistic individuals who are hyperresponsive to sensory stimuli, particularly in the auditory domain [30]. Thus, the potential relationship between the impact of problem behaviour and owner neurodiversity should be considered, in both research and practice. The owner’s current circumstances will not only affect the risk of certain issues (and related burden) but also affect the concerns they have more directly. During the COVID-19 pandemic, when owners spent a lot of time in their homes in close contact with their dogs, attention-seeking and barking were common issues [31,32]. During this period of social seclusion, aggression towards strangers was probably less of an issue, although aggression towards owners appeared to increase over time for owners who continued to work from home [33]. Since the release of restrictions, there is some evidence to suggest an increased risk of problems relating to fear and aggressive behaviour [34]. Specific life events may also affect the perceived burden of ownership. It has been reported that elderly individuals and young couples with a growing family feel overwhelmed by a puppy with challenging behaviours [35], increasing the risk of relinquishment by these groups.

Table 1.

Reported negative impacts (or associations) of dog behavioural problems on owner emotions/moods and life satisfaction.

Table 1.

Reported negative impacts (or associations) of dog behavioural problems on owner emotions/moods and life satisfaction.

| Study | Design * | Sample | Owner Emotions/ Moods/Life Satisfaction | Dog Behavioural Problems | Type of Finding/How It Was Measured |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barcelos et al., 2023 [23] | Cohort study (four surveys with closed questions) | 709 dog owners over 18 years old | Worse hedonic well-being (i.e., emotions, mood, and life satisfaction), loneliness. | Aggression (e.g., growling, trying to bite, lunging, offensive bark) Note: other problems assessed were not associated with hedonic well-being, i.e., fearful behaviour, distinct barking episodes, destroying/chewing/stealing, dog out of control, and house soiling | Significant between-person correlation. MHC-SF scale [36] for hedonic well-being. Owner-reported frequency of behavioural problems |

| Barcelos et al., 2021 [25] | Survey (closed questions) | 1030 dog owners over 18 years old | Emotions of negative valence and high arousal (e.g., annoyance, anger, stress, worry, frustration), and low arousal (e.g., sadness and tiredness) increased. Positive emotions reduced (e.g., happiness, calmness). Decrease in life satisfaction. | Aggression (e.g., growling, trying to bite, biting), sensory-related (e.g., barking, house soiling), dog out of control (e.g., dog pulls on the lead, does not respond to recall), other unwanted behaviours (e.g., destruction of items, attention seeking, separation-related problems) | Significantly different than ‘no impact’—owner-reported impacts |

| Morgan et al., 2020 [37] | Survey (closed questions) | 3138 dog owners over 18 years old | Stress and worry during the COVID-19 pandemic—were part of a quality of life index created by the authors | New behavioural problems | Significant association between the index and new dog behavioural problems in the COVID-19 pandemic. Owner-reported emergence of behavioural problems. |

| Bradley and Bennett, 2015 [38] | Survey (closed questions) | 66 dog owners over 18 years old and with chronic pain disorder | Stress | Dog disobedience Note: dog nervousness was also tested, and it was not correlated with stress | Significant correlation. 5-point Likert scale for dog disobedience and nervousness. DASS-21 scale [39] for owner stress |

| Barcelos et al., 2020 [24] | Focus groups | 35 dog owners over 18 years old | Emotions of negative valence and high arousal (e.g., annoyance, anger, stress, worry, frustration), and low arousal (e.g., sadness and tiredness) | Barking, aggression in general, biting/trying to bite, lunging, growling, chewing or destroying objects, stealing food or objects, house soiling with faeces, rolling on poo, eating poo (coprophagia), puppy-related behaviours, farting, snoring | Owner-reported impacts |

| Barcelos et al., 2021 [26] | Interviews | 36 autistic adults who owned a dog and were over 18 years old | Emotions of negative valence and high arousal (e.g., annoyance, anger, stress, worry, frustration), and low arousal (e.g., sadness and tiredness) triggered. Positive emotions reduced (e.g., happiness, calmness). | Sensory-related (e.g., barking, house soiling, snoring), dog out of control (e.g., poor response to recall, pulling on the lead), dog disrupts owner personal space (e.g., attention seeking), unruly behaviours (e.g., destruction of objects, hyperactivity), fearful/aggressive behaviours (e.g., biting, fear of noises), separation-related problems, sniffing too much in walks, poor appetite. | Owner-reported impacts |

| Corrêa et al., 2021 [27] | Interviews | 32 dog owners over 18 years old | Emotions of negative valence and high arousal (e.g., annoyance, anger, stress, worry, frustration), and low arousal (e.g., sadness and tiredness) | Barking/lunging/growling at others (people or dogs), destroying/moving/stealing things, chasing animals or vehicles, barking in the house, house soiling, pulling on the lead | Owner-reported impacts |

| Smith et al., 2017 [40] | Dog-walk-along interviews and participatory analysis session | 13 dog owners over 18 years old and with one or more long-term health conditions | Frustration | Ignoring owner’s commands | Owner-reported impacts during a dog walk |

| DiGiacomo et al., 1998 [35] | Interviews (one-to-one and family units) | 48 people over 18 years old who just surrendered their pets—27 were dogs | Fear, overwhelm | Puppy’s “wild” behaviour, puppy’s energetic behaviour | Owner-reported impacts |

| Love, 2021 [28] | Survey (open-ended questions) | 25 dog owners, over 18 years old, with recent experiences of suicidal thoughts or behaviours. 71 pet owners in total | Stress, frustration, sadness | Behavioural problems in general | Owner-reported impacts |

| Owczarczak-Garstecka et al., 2021 [31] | Survey (open-ended questions) | 584 dog owners over 18 years old | Stress | Barking | Owner-reported impacts during the COVID-19 pandemic |

| Buller and Ballantyne, 2020 [15] | Survey (open-ended questions) | 38 owners, over 18 years old, of dogs with behavioural problems. 39 pet owners in total. | Anger, frustration, stress, worry, fear, sadness, embarrassment, disappointment, resentment, fatigue, tension, overwhelm | Behavioural problems in general, aggressiveness, reactiveness, separation-related behaviours | Owner-reported impacts |

| Applebaum et al., 2020 [32] | Survey (open-ended questions) | 2254 pet owners over 18 years old | Stress, irritation, concern, annoyance | Puppy “going crazy”, puppy attention seeking, attention seeking in general, separation anxiety, barking, behavioural problems in general | Owner-reported impacts during the COVID-19 pandemic |

* All studies except Barcelos et al. [23] were cross-sectional/single-time point sampled.

It is also worth noting that positive emotions have also been occasionally reported in relation to the occurrence of behavioural problems, but especially in relation to their management [15,24,26,27]. For instance, in [15], one participant mentioned that they felt pride when the behaviour of the dog was better than expected. For those working to resolve problems, greater awareness of this phenomenon and validation of such feelings within clients might help significantly in the process of alleviating the burden, once a client starts to seek help, and also be used to help motivate the necessary human behaviour change required for resolution of the problem. By contrast, positive emotions associated with the occurrence of problem behaviour can be unhelpful. Barcelos et al. [24] found that owners could view a dog stealing food/objects as something both negative and positive (i.e., annoying and funny). Burn [41] has previously highlighted the concerns of viewing abnormal behaviour such as excessive, repetitive tail-chasing in dogs as funny or in a light-hearted way (a phenomenon exacerbated by social media). This can result in a failure to seek help or even reinforcement of an issue, which can compromise dog welfare (see [42]).

4. Dog Behavioural Problems and Owner Life Functioning (Eudaimonic Well-Being)

Nine studies were included in this section (Table 2). In seven of them [15,24,25,26,27,40,43], owners’ relations with other people were perceived to deteriorate due to the behavioural problems of their dogs. Interpersonal conflicts occurred as a direct result of the problem (e.g., due to the dog mounting another dog [43]), and also indirectly through owner social isolation/avoidance to prevent the occurrence of the behavioural problem [15]. These findings should not be taken lightly. Social isolation and loneliness are associated with an increased risk of physical and psychological disorders, such as cardiovascular diseases, anxiety and depression [44,45]. As discussed in the previous section, owners of dogs who show aggressive behaviour more often feel lonelier [23].

Other elements of owner eudaimonic well-being also seem to be negatively affected by dogs’ behavioural problems, particularly environmental mastery, e.g., due to difficulties with managing their own time and day-to-day activities around the specific needs of their dog [15] and self-acceptance, e.g., for not being able to successfully manage/‘control’ the behaviour of the dog [24].

Two quantitative studies [23,46] found significant associations between fear/anxiety-related behaviours in dogs and worse eudaimonic well-being in their owners, such as lower self-esteem. In Buller and Ballantyne’s [15] qualitative investigation, it was reported that owners of dogs with separation-related issues often struggle to manage their lives and social activities, as they feel the dog cannot be left alone at home for prolonged periods. Aggressive behaviour, as mentioned above, and a sense that the dog is beyond the control of the owner (e.g., pulling on the lead, poor recall response) were reported as detrimental to eudaimonic well-being in various studies [24,25,26,27,40]. Thus, it seems reasonable to suppose that specific behaviour problems negatively impact owners’ life functioning in diverse ways.

Table 2.

Reported negative impacts (or associations) of dog behavioural problems on elements of owners’ eudaimonic well-being (life functioning).

Table 2.

Reported negative impacts (or associations) of dog behavioural problems on elements of owners’ eudaimonic well-being (life functioning).

| Study | Design * | Sample | Owner Eudaimonic Well-Being | Dog Behavioural Problems | Type of Finding/How It Was Measured |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barcelos et al., 2023 [23] | Cohort study (four surveys with closed questions) | 709 dog owners over 18 years old | Worse eudaimonic well-being in general | Fearful/anxious dog behaviour (e.g., fear of noises, of other individuals, separation anxiety) | Significant within-person correlation. MHC-SF scale for eudaimonic well-being [36] Owner-reported frequency of behavioural problems. |

| Clarke et al., 2023 [46] | Survey (closed questions) | 497 dog owners over 18 years old | Worse self-esteem | Non-social fear Note: other behavioural problems were tested in this study but were not significant. | Significant association. |

| Barcelos et al., 2021 [25] | Survey (closed questions) | 1030 dog owners over 18 years old | Worse positive relations with others, autonomy, and environmental mastery. Note: personal growth, self-acceptance, and purpose in life were also tested but were not associated with any behavioural problem. | Aggression (e.g., growling, trying to bite, biting), sensory-related (e.g., barking, house soiling), dog out of control (e.g., dog pulls on the lead, does not respond to recall), other unwanted behaviours (e.g., destruction of items, attention seeking, separation-related problems) | Significantly different than ‘no impact’—owner-reported impacts |

| Barcelos et al., 2020 [24] | Focus groups | 35 dog owners over 18 years old | Worse positive relations with others and self-acceptance | Barking, aggression in general, barking, biting/trying to bite, lunging. | Owner-reported impacts |

| Barcelos et al., 2021 [26] | Interviews | 36 autistic adults who owned a dog and were over 18 years old | Worse positive relations with others, environmental mastery, autonomy, self-acceptance, and personal growth. | Dog out of control (e.g., poor response to recall, pulling on the lead), sensory-related (e.g., barking, house soiling, snoring), unruly behaviours (e.g., destruction of objects, hyperactivity), fearful/aggressive behaviours (e.g., biting, fear of noises). | Owner-reported impacts |

| Corrêa et al., 2021 [27] | Interviews | 32 dog owners over 18 years old | Worse positive relations with others | Barking/lunging/growling at others (people or dogs), destroying/moving/stealing things, barking in the house, house soiling. | Owner-reported impacts |

| Smith et al., 2017 [40] | Dog-walk-along interviews and participatory analysis session | 13 dog owners over 18 years old and with one or more long-term health conditions | Worse positive relations with others (e.g., conflict with other dog owners, prevents owner from interacting with other dog walkers) | Dog anti-social behaviour, dog aggression | Owner-reported impacts during a dog walk |

| Buller and Ballantyne, 2020 [15] | Survey (open-ended questions) | 38 owners, over 18 years old, of dogs with behavioural problems. 39 pet owners in total. | Worse positive relations with others (e.g., issues with house guests, social isolation), environmental mastery (e.g., time management issues), self-accepting (e.g., hating new version of oneself) | Behavioural problems in general, separation-related problems | Owner-reported impacts |

| Jackson, 2012 [43] | Observational study, ethnographic | Owners in a dog park. No further details. | Worse positive relations with others | Mounting another dog | The researcher’s observations (field notes) |

* All studies except Barcelos et al. [23] were cross-sectional/single-time point sampled.

5. Dog Behavioural Problems, Owner Mental Health Problems and Caregiver Burden

In 12 of the behavioural studies reviewed, there was an association between dog behavioural problems and owner burden or mental health (Table 3). Anxiety, depression, and suicidal ideation were the main mental health problems evaluated and found to be associated with dog behavioural problems [23,38,46,47,48]. In addition, in a qualitative study with pet owners with recent experience of suicidal thoughts or behaviours, pet behavioural problems were perceived as a risk factor for these suicidal thoughts [28].

Kuntz et al. [19], in a retrospective analysis of clinical records of owners of dogs with behavioural problems, claimed that proportionally more of these owners have a clinically meaningful burden than owners of dogs with other chronic conditions [49,50], with the average burden score also higher for owners of dogs with behavioural problems [51,52]. Thus, it is likely that behavioural problems cause a significant burden for owners despite it perhaps being less recognized/established than the burden of those caring for animals with chronic physical conditions such as cancer, skin disease and osteoarthritis. Interestingly, Barrios et al. [53] recently adapted the Zarit carer burden scale [54], used in human–human relationships, for owners of dogs with behavioural problems, with some items directly mentioning behavioural issues, e.g., “do you feel demotivated since your dog started to show undesired behavior?”. Although this scale [53] needs further psychometric validation, and the one used by Kuntz et al. [19] is not specifically tailored for owners of pets with behavioural problems, they open a way for more-routine monitoring of owner burden.

In terms of which behavioural problems appear most important regarding burden and mental health problems, aggression and fear/anxiety-related behaviours (e.g., fear of noises, separation-related problems) seem to be particularly triggering [23,46,47,48]. Kuntz et al. [19] report that bite history was linked with a higher caregiver burden score and, in Barcelos et al.’s [23] cohort study, owners of dogs who showed aggressive behaviours more often had more symptoms of depression and anxiety than other owners.

In a case–control study of 119 healthy matched controls [55] examining which signs/behaviours of chronic/terminal illness in pets were most strongly correlated with client burden, the following were found to be most impactful: weakness, appearing sad/depressed or anxious, appearing to have pain/discomfort, change in personality, frequent urination, excessive sleeping/lethargy. Many of these signs occur in various problem behaviour cases, with pain also being increasingly recognized in many cases [14,56]. Other findings from this study indicate that the burden felt also increased due to the frequency of signs/behaviours, the owner’s sense of control and reaction to the signs/behaviours (e.g., not at all bothered, extremely bothered). These results suggest that owners of problem behaviour dogs might be under particular strain and thus at greater risk of mental health issues compared to owners faced with many other clinical conditions affecting dogs.

Table 3.

Reported negative impacts (or associations) of dog behavioural problems on owner mental health problems and caregiver burden.

Table 3.

Reported negative impacts (or associations) of dog behavioural problems on owner mental health problems and caregiver burden.

| Study | Design * | Sample | Owner Eudaimonic Well-Being | Dog Behavioural Problems | Type of Finding/How It Was Measured |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barcelos et al., 2023 [23] | Cohort study (four surveys with closed questions) | 709 dog owners over 18 years old | Depression, anxiety, suicidal ideation. | Aggressive dog behaviour (e.g., growling, trying to bite, lunging, offensive bark), fearful/anxious dog behaviour (e.g., fear of noises, of other individuals, separation anxiety), dog out of control (e.g., poor recall, pulls on the lead) | Significant within and between-person correlation. GAD7 [57] and PHQ-9 [58] scales for anxiety and depression, respectively. One item for suicidal ideation. Owner-reported frequency of behavioural problems |

| Clarke et al., 2023 [46] | Survey (closed questions) | 497 dog owners over 18 years old | Depression and anxiety | Attachment and attention seeking, separation-related behaviours, stranger-directed aggression, stranger-directed fear, non-social fear, dog-directed fear, touch sensitivity, excitability Note: other behavioural problems were tested in this study but were not significant | Significant association BDI scale for depression [59], GAD-7 for anxiety [57], and C-BARQ [60] for dog behavioural problems |

| Pereira et al., 2021 [48] | Survey (closed questions) | 1172 dog owners over 18 years old | Trait anxiety | Dog’s fear and anxiety-related behaviours | Significant association. STAI-Trait Inventory for owner anxiety [48], C-BARQ [60] for dog fear and anxiety-related behaviours |

| Shoesmith et al., 2021 [61] | Survey (closed questions) | 5323 animal owners—3719 (69.9%) had dogs | Poorer mental health since COVID-19 lockdown | More-negative changes in the behaviour and welfare of the animal | Mental health was measured with the SF-36 (MHI-5) scale [62] |

| Dodman et al., 2018 [47] | Survey (closed questions) | 1564 dog owners over 18 years old and members of the Center for Canine Behavior Studies | Moderate depression Note: severe depression was not associated with behavioural problems | Familiar dog aggression, urinating when left alone, defecating when left alone Note: other behavioural problems were tested in this study but were not significant | Significant association. The BDI scale for owner depression [59], the mini C-BARQ [63] for behavioural problems |

| Bradley and Bennett, 2015 [38] | Survey (closed questions) | 66 dog owners over 18 years old and with chronic pain disorder | Depression and anxiety | Lower dog friendliness Note: dog nervousness and disobedience were also tested, and they were not correlated with stress | Significant correlation. 5-point Likert scale for dog friendliness. DASS-21 scale [39] for owner depression and anxiety |

| Love, 2021 [28] | Survey (open-ended questions) | 25 dog owners, over 18 years old, with recent experiences of suicidal thoughts or behaviours. 71 pet owners in total | Suicidal thoughts (risk factor for it) | Behavioural problems in general | Owner-reported impacts |

| Spitznagel et al., 2018 [55] | Case-control study (closed questions) | Phase 1: 238 pet owners (176, 73.9% dog owners, 62, 26.1% cat owners). Phase 2: 602 pet owners (424, 70.4% dog owners, 178, 29.6% cat owners) | Caregiver burden | 25 signs/problems linked with chronic/terminal illness in pets were assessed and correlated with owner burden, but the most robust links were found for weakness, appearing sad/depressed or anxious, appearing to have pain/discomfort, change in personality, frequent urination, and excessive sleeping/lethargy. | One-tail correlation at p < 0.001 Pet Problem Severity scale created by the authors to measure signs/behaviours. Burden measured with the Zarit Burden Interview [55]. |

| Buller and Ballantyne, 2020 [15] | Survey (open-ended questions) | 38 owners, over 18 years old, of dogs with behavioural problems. 39 pet owners in total. | Burden | Behavioural problems in general, anxiety in the dog | Owner-reported impacts |

| DiGiacomo et al., 1998 [35] | Interviews (one-to-one and family units) | 48 people over 18 years old who just surrendered their pets—27 were dogs | Burden | Puppy’s energetic behaviour, puppy’s behavioural problems | Owner-reported impacts |

| Kuntz et al., 2023 [19] | Scale validation through retrospective analysis of clinical records from Jan 2020 to Dec 2020 from a specialty behaviour practice | 333 owners, over 18 years old, of dogs with behavioural problems—records from a private specialty behaviour practice | Burden—68.5% of the sample had clinically meaningful burden | Behavioural problems in general, bite history associated with higher score. Note: other behavioural problems were not associated with burden score. | Burden measured with the Zarit Burden Interview [19]. Significant association with bite history. |

| Barrios et al., 2022 [53] | Scale development—survey (closed questions) | 156 people over 18 years old who owned a dog diagnosed with some type of behavioural disorder within the previous six months | Burden/burnout—9% of the sample had high-medium burnout symptoms due to caring for a dog with behavioural disorders. 41% had medium-low burnout, and 50% had low burnout. | Behavioural problems in general | Burnout scale adapted for owners of dogs with behaviour disorders |

* All studies except Barcelos et al. [23] were cross-sectional/single-time point sampled.

It is important to note that owner well-being might also affect the behaviour of their dogs through mechanisms such as emotional contagion or the way they interact with their dogs [46,47,64,65]. Indeed, Clarke et al. [46] report that owners believe that their dogs are responsive to their mood, particularly to their anxiety and depression, with dogs being their ‘mirrors’ or ‘shadows’. Handler depression and post-traumatic stress disorder have also been shown prospectively to predict dog behavioural problems [66]. Dodman et al. [47] report that owner depression is associated with a tendency to use aversive or punitive training methods, and it has been suggested elsewhere that this might increase the risk of problem behaviour (e.g., [67]). It seems reasonable to suppose that there is a bidirectional relationship between dog behavioural problems and owner well-being [46]. Such a bidirectional relationship is also supported by the results of Barcelos et al.’s [23] longitudinal study, in which a higher frequency of behavioural problems was correlated with various aspects of poorer owner well-being (Table 1, Table 2 and Table 3).

Finally, there are also the occasional findings that link poor owner mental health with more favourable problem behaviour issues. Moderate owner depression was associated with lower odds of stranger-directed aggression [47], and poorer owner mental health pre-lockdown was associated with fewer negative changes in the welfare and behaviour of their animal [61]. The reasons for these findings are not entirely clear and deserve further attention.

Despite the potential negative effects of dog behavioural problems described in this section, it is important to keep in mind that the reported benefits of dog ownership are generally seen to outweigh its negative impacts [24,25,26,27,28]. Thus, there is a need to focus on the development of preventive and remedial measures to minimize these risks.

6. Intervention in Human–Dog Dyads Challenged by Dog Behavioural Problems

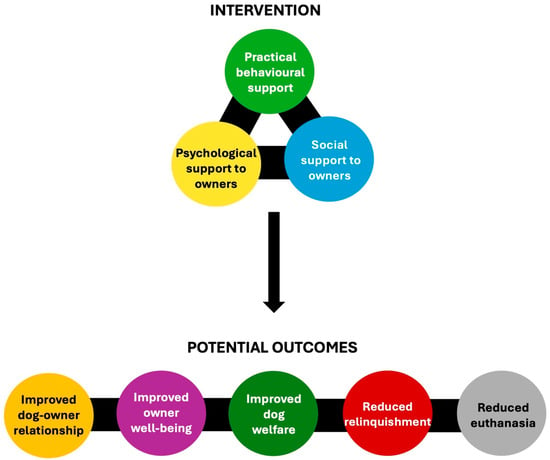

In order to prevent and reduce the negative impacts of dog behavioural problems on both human well-being and dog welfare, we propose a three-pronged intervention (Figure 1). This approach is based on the reported coping strategies used by owners of pets with behavioural problems (see [15]), the current authors’ experiences with owners of dogs with behavioural problems, and suggestions described in the reviewed literature (e.g., [19]).

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of three key aspects of the intervention that should be considered in cases where dog behavioural problems worsen owner well-being, and the potential outcomes of successful intervention.

6.1. Practical Behavioural Support for the Dyad

It may seem obvious, but practical support from animal behaviour professionals, such as veterinarians specialized in behaviour and clinical animal behaviourists, is essential for owners of dogs with behavioural problems. However, clients may not be aware of these services or how to discern a quality provider. Outside of the veterinary profession, there is little truly independent regulation (despite the claims of various organisations), so standards can vary enormously, leaving clients at a potential loss with regard to whom they should seek for help. Clients frequently raise behavioural issues in the course of routine preventive consultations at the veterinary clinic [68], and this, along with the common involvement of medical issues in problem behaviour cases [69], indicates that the veterinarian has a particularly important responsibility in this regard. Even if they are not able to manage the issue directly, they should be in a position to make a professional recommendation [69]. The behavioural professional should not simply provide prescriptive training solutions, but should be able to provide expert guidance on how to manage the problem, according to the owner’s capabilities, opportunities and motivations [70]. This requires an understanding of human psychology and coaching as well as animal training science. An important part of the process is helping to support, validate and normalize the client’s experiences [15]. Unmet expectations on how a dog should behave are a big issue in this regard, due to the different understandings of what is appropriate and inappropriate canine behaviour [71,72]. Behavioural professionals can certainly help in this process. For instance, people who have recently acquired a dog are often challenged by unmet expectations, as they are still getting accustomed to the behaviour of the dog, adjusting their own routines to accommodate the dog, are not yet very attached to the animal, and the dog is also getting used to the owner’s routine [71,73]. Professional support at this early stage, e.g., through behaviour consultation in which realistic expectations can be developed alongside minimally intrusive training and management plans, can be a crucial step to preventing the escalation of an issue to the point of potential relinquishment.

There is a myriad of conflicting information on approaches to handling specific behavioural problems (e.g., from websites, social media experts, dog trainers), and, unfortunately, poor choices may worsen an already problematic behaviour. Therefore, a safer route when choosing a professional or approach is to use well-recognized animal behaviour/welfare entities. For those living in Europe, a list of veterinarians specialized in animal welfare and behavioural medicine is available on the website of the European College of Animal Welfare and Behavioural Medicine (https://www.ecawbm.org/diplomates-list, accessed on 29 May 2024), and similar lists exist for those living in North America (https://www.dacvb.org/search/custom.asp?id=5985, accessed on 29 May 2024) and Australasia (https://www.anzcvs.org.au/chapters/veterinary+behaviour+chapter, accessed on 29 May 2024). In addition, there are other credible certifications for behavioural professionals that are not necessarily veterinarians, such as Certificated Clinical Animal Behaviourists (CCAB) in the UK (https://www.ccab.uk, accessed on 29 May 2024), and Certified Applied Animal Behaviorists (CAAB) in the US (https://www.animalbehaviorsociety.org/web/committees-applied-behavior-caab.php, accessed on 29 May 2024).

Owners of dogs with behavioural problems often complain that they cannot afford a behavioural professional [15,35] or that the behavioural issues cause a heavy financial burden [15]. This can lead pet owners to preferentially choose free services [74], including social media and TV [75]. Unfortunately, these channels often promote the spectacle of problem behaviour management, potentially at the expense of animal welfare (see, for example, Jackson-Shebetta’s [76] analysis of one particular series), and such approaches can create their own, or exacerbate, existing problems [75]. The lack of easily identifiable, high-quality free options likely contributes to the high prevalence of clinically meaningful caregiver burden among owners of dogs with behavioural problems [19]. However, there is also a need for owners to recognize the true cost of providing professional behaviour support services and for this issue to be effectively communicated to them. There is a moral dimension to making such dog behavioural services accessible across the sociodemographic spectrum [19], and a number of dog rescue organisations and shelters are increasingly offering such a service for free, which may also help reduce their own intake. Indeed, it has been reported that most owners who cited behavioural problems as the primary reason for dog relinquishment indicated that they would keep the dog if the problems could be corrected [71]. There is thus a need not only to make high-quality professional behavioural support more visible and accessible but also for independent accreditation to ensure the quality of the service.

6.2. Social Support for Owners

Owners of pets with behavioural problems commonly feel isolated and judged due to the lack of understanding and unsupportive reactions of the broader community (e.g., trainers, veterinarians, strangers), friends, and family members [15]. Findings from the current literature review (Table 2) indicate that dog behavioural problems are often detrimental to social interactions, either as a direct result of the problematic behaviour or indirectly through self-imposed social avoidance/isolation by the owner to prevent the occurrence of the problematic behaviour. Therefore, it is important to help owners of dogs with behavioural problems feel more socially supported and understand that they are not alone.

Peer support is recognized as a genuine recovery-focused intervention for mental health issues (e.g., [77,78]) and is advocated in policy guidelines worldwide (e.g., [79,80,81,82]). Furthermore, studies indicate that participation in support groups can be beneficial for both neurotypical and neurodivergent individuals [83,84]. Support can be unidirectional, provided by a paid peer support worker to a recipient, or it can be mutual, as seen in support groups [85]. Peer-delivered services are typically complex interventions and can be offered either on an individual basis or through group interventions [86].

Buller and Ballantyne [15] highlight how owners of pets with behavioural problems need support/discussion groups involving other people dealing with similar issues, as a way to share their personal experiences and be understood by others. In this regard, social media can be a force for good, with groups like the “Reactive and Aggressive Dog Support Group” on Facebook aiming to support owners with these problems. Although these sites might help build a sense of community, they have the potential to also be a source of misinformation on how to manage the problem. Thus, support groups moderated by appropriate professionals or professional organisations are preferable. Alternatively, specific sessions might be made available to owners through clinical behaviour specialists. These sessions do not need to be complexly structured, but they should focus on the psychological needs of the client and be run by an appropriately qualified professional. Owners perhaps simply need an opportunity to share their experiences and their feelings with people who understand them, which will help build a sense of community and belongingness.

6.3. Psychological Support to Owners

Although the precise causal nature of the relationship between behavioural problems in dogs and mental health problems in humans might be debatable, it is unquestionable that many owners of dogs with behavioural problems would benefit from psychological support. For this reason, serious consideration should be given to a closer relationship between animal behaviour professionals and those working in human mental health and/or social work services. This could be achieved by developing guidelines for animal behaviour professionals on how and when to make mental health referral decisions to suitable professionals or services. Recent years have seen the beginnings of the academic discipline of veterinary social work, with an emphasis on grief at the loss of a pet, compassion fatigue, crisis intervention relating to the human–animal bond and animal-assisted interventions [87,88,89]. However, the inclusion of the needs of the clients of those working in the field of problem behaviour management would be a useful additional specialization. Collaborative relationships like this will help ensure better human well-being and better animal welfare [15,19]. Indeed, Kuntz et al. [19] suggest that the assessment of caregiver burden should be part of the intake evaluation of the dog behavioural consultation, as a way to identify those with a clinically meaningful burden, provide adequate support and reduce the complexity of the behavioural treatment plan. Developing such a culture would undoubtedly help many owners, transform awareness of the issues discussed here and help to remove any related stigma. Finally, in cases where the dog is relinquished or euthanized due to behavioural problems, psychological and social support to the owner may also be helpful.

7. Suggestions for Future Directions for Research in This Field

Considering that dog behavioural problems are one of the main reasons for dog relinquishment [6,7,8,9,10,11] and that owners of dogs with behavioural problems have greater intention to relinquish their animals [4,5], there is clearly a need for applied research. Perhaps the most obvious study with real-world impact would be a large-scale randomized controlled trial assessing the impact of a complex intervention based on a multidisciplinary assessment of practical behavioural support, social support, and psychological support on relinquishment reduction and owner well-being. Complex interventions are interventions that contain several interacting components [90]; in the latter case, these would include the three interventional approaches described above and at least dog relinquishment and owner well-being as outcomes of interest. The control for such a study might be current best practice by a qualified clinical animal behaviourist. Such a study is entirely feasible for a large rescue organisation (or network of organisations) with sufficient funds.

However, in the absence of such funding, it is likely that research will be on a much smaller scale. Buller and Ballantyne’s work [15] is the most comprehensive study focused on understanding the various impacts of pet behavioural problems on human well-being. Our review serves to highlight not only the importance of this work but also the need for more research attention to be given to this area. To cover the enormous gaps in our knowledge, there is a need for further exploratory studies assessing in what ways specific behavioural problems of pets affect the well-being of their owners and what strategies are effective in improving owner well-being in these situations.

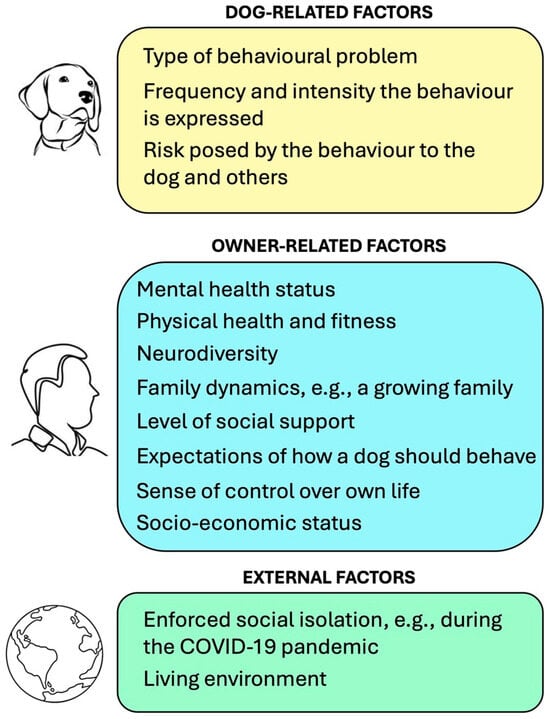

In Figure 2, some of the factors that might influence the impacts of dog behavioural problems on owner well-being are highlighted. For example, the owner’s fitness/physical health might affect how the dog’s behaviour of pulling on the lead is perceived. None of the studies in our review targeted people under 18 years old; this is a significant gap in our knowledge given the potentially important effects of pets on child development [91,92,93]. Thus, future investigations should explore how children are affected by the behavioural problems of dogs in their home and what can be done to help them.

Figure 2.

Some potential factors to consider that influence how dog behavioural problems affect owner well-being.

Importantly, longitudinal studies to better understand the relationship between dog behavioural problems and human well-being are also lacking in the literature. To date, only one study has attempted to model the potential causal nature of the relationship between dog behavioural problems and various well-being outcomes [23]. In this, a four-week cohort study involving a general population of dog owners, no significant causal effects were found. Clearly, more targeted designs are required.

8. Conclusions

It is clear that dog behavioural problems may be detrimental to hedonic well-being in owners, particularly increasing negative emotions of high arousal (e.g., annoyance and frustration), and to eudaimonic well-being, especially by reducing social interactions. It may also increase caregiver burden (i.e., strain borne by the carer) and symptoms of depression and anxiety in their owners. However, there is a notable lack of research on this important public health, dog welfare and practical issue. Owners of dogs with behavioural problems are likely to need and benefit from a variety of external professional sources of support, particularly in three areas: practical support on how to deal with and perceive the behaviour of their dogs, social support from other individuals who are dealing with similar issues, and psychological support from mental health professionals. Considering the myriad of misinformation and professionals available, there is a pressing need to ensure the accessibility of high-quality services to owners across the socio-economic spectrum. This need can only be met by greater engagement from both practising professionals and researchers in the field.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/pets1010007/s1, Table S1. The 21 papers included in the literature review.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: A.M.B. Literature search: A.M.B., N.K. and D.M. Writing—original draft preparation: A.M.B. Writing—review and editing: A.M.B., N.K. and D.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors received no funding for this work.

Acknowledgments

We thank the members of the Human-Animal Interaction Research Group of the University of Edinburgh for sharing some ideas on how to support owners of dogs with behavioural problems.

Conflicts of Interest

DSM is a specialist in Veterinary Behavioural Medicine recognised by the Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons, and Committee member of CCAB Ltd. The authors declare no other potential conflicts of interest.

References

- Mugford, R.A. Behavioural disorders of dogs. In The Behavioural Biology of Dogs; Jensen, P., Ed.; Cromwell Press: Trowbridge, UK, 2007; pp. 225–242. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, G. Personal Construct Psychology; Norton: New York, NY, USA, 1955. [Google Scholar]

- Mills, D.S.; Mills, C.B. A survey of the behaviour of UK household dogs. In Proceedings of the 4th International Veterinary Behaviour Meeting, Caloundra, Australia, 18–20 August 2003; Volume 352, pp. 93–98. [Google Scholar]

- Luna-Cortés, G. The influence of the dimensions of perceived value on keepers’ satisfaction and intention to abandon. Soc. Anim. 2022, 23, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luna-Cortés, G. Companion Dog Routine Inventory: Scale Validation and the effect of routine on the human–dog relationship. Anthrozoos 2022, 35, 527–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diesel, G.; Brodbelt, D.; Pfeiffer, D.U. Characteristics of relinquished dogs and their owners at 14 rehoming centers in the United Kingdom. J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci. 2010, 13, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friend, J.R.; Bench, C.J. Evaluating factors influencing dog post-adoptive return in a Canadian animal shelter. Anim. Welf. 2020, 29, 399–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, J.B.H.; Sandoe, P.; Nielsen, S.S. Owner-related reasons matter more than behavioural problems—A study of why owners relinquished dogs and cats to a Danish animal shelter from 1996 to 2017. Animals 2020, 10, 1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- New, J.C., Jr.; Salman, M.D.; King, M.; Scarlett, J.M.; Kass, P.H.; Hutchison, J.M. Characteristics of shelter-relinquished animals and their owners compared with animals and their owners in US pet-owning households. J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci. 2000, 3, 179–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patronek, G.J.; Glickman, L.T.; Beck, A.M.; McCabe, G.P.; Ecker, C. Risk factors for relinquishment of dogs to an animal shelter. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 1996, 209, 572–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powdrill-Wells, N.; Taylor, S.; Melfi, V. Reducing dog relinquishment to rescue centres due to behaviour problems: Identifying cases to target with an advice intervention at the point of Relinquishment Request. Animals 2021, 11, 2766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Wilson, B.; Masters, S.; van Rooy, D.; McGreevy, P.D. Mortality resulting from undesirable behaviours in dogs aged three years and under attending primary-care veterinary practices in Australia. Animals 2021, 11, 493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreschel, N.A. The effects of fear and anxiety on health and lifespan in pet dogs. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2010, 125, 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, D.S.; Coutts, F.M.; McPeake, K.J. Behavior Problems Associated with Pain and Paresthesia. Vet. Clin. Small Anim. Pract. 2024, 54, 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buller, K.; Ballantyne, K.C. Living with and loving a pet with behavioral problems: Pet owners’ experiences. J. Vet. Behav. 2020, 37, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, E.; Bennett, P.C.; McGreevy, P.D. Current perspectives on attachment and bonding in the dog–human dyad. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2015, 8, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Suh, E.M.; Lucas, R.E.; Smith, H.L. Subjective well-being: Three decades of progress. Psychol. Bull. 1999, 125, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C.D. Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1989, 57, 1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuntz, K.; Ballantyne, K.C.; Cousins, E.; Spitznagel, M.B. Assessment of caregiver burden in owners of dogs with behavioral problems and factors related to its presence. J. Vet. Behav. 2023, 64, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohlmeijer, E.; Westerhof, G. The model for sustainable mental health: Future directions for integrating positive psychology into mental health care. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 747999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Agteren, J.; Iasiello, M.; Lo, L.; Bartholomaeus, J.; Kopsaftis, Z.; Carey, M.; Kyrios, M. A systematic review and meta-analysis of psychological interventions to improve mental wellbeing. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2021, 5, 631–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wąsowicz, G.; Mizak, S.; Krawiec, J.; Białaszek, W. Mental health, well-being, and psychological flexibility in the stressful times of the COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 647975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barcelos, A.M.; Kargas, N.; Assheton, P.; Maltby, J.; Hall, S.; Mills, D.S. Dog owner mental health is associated with dog behavioural problems, dog care and dog-facilitated social interaction: A prospective cohort study. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 21734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barcelos, A.M.; Kargas, N.; Maltby, J.; Hall, S.; Mills, D.S. A framework for understanding how activities associated with dog ownership relate to human well-being. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 11363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barcelos, A.M.; Kargas, N.; Maltby, J.; Hall, S.; Assheton, P.; Mills, D.S. Theoretical foundations to the impact of dog-related activities on human hedonic well-being, life satisfaction and eudaimonic well-being. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barcelos, A.M.; Kargas, N.; Packham, C.; Mills, D.S. Understanding the impact of dog ownership on autistic adults: Implications for mental health and suicide prevention. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 23655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corrêa, G.F.; Barcelos, A.M.; Mills, D.S. Dog-related activities and human well-being in Brazilian dog owners: A framework and cross-cultural comparison with a British study. Sci. Prog. 2021, 104, 00368504211050277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Love, H.A. Best friends come in all breeds: The role of pets in suicidality. Anthrozoos 2021, 34, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Farrell, V. Owner attitudes and dog behaviour problems. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 1997, 52, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, K.L.; Campi, E.; Baranek, G.T. Associations among sensory hyperresponsiveness, restricted and repetitive behaviors, and anxiety in autism: An integrated systematic review. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 2021, 83, 101763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owczarczak-Garstecka, S.C.; Graham, T.M.; Archer, D.C.; Westgarth, C. Dog walking before and during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown: Experiences of UK dog owners. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Applebaum, J.W.; Tomlinson, C.A.; Matijczak, A.; McDonald, S.E.; Zsembik, B.A. The concerns, difficulties, and stressors of caring for pets during covid-19: Results from a large survey of U.S. pet owners. Animals 2020, 10, 1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherwell, E.G.; Panteli, E.; Krulik, T.; Dilley, A.; Root-Gutteridge, H.; Mills, D.S. Changes in dog behaviour associated with the COVID-19 lockdown, pre-existing separation-related problems and alterations in owner behaviour. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacchettino, L.; Gatta, C.; Chirico, A.; Avallone, L.; Napolitano, F.; d’Angelo, D. Puppies raised during the COVID-19 lockdown showed fearful and aggressive behaviors in adulthood: An Italian survey. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DiGiacomo, N.; Arluke, A.; Patronek, G. Surrendering pets to shelters: The relinquisher’s perspective. Anthrozoos 1998, 11, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamers, S.M.A.; Westerhof, G.J.; Bohlmeijer, E.T.; ten Klooster, P.M.; Keyes, C.L.M. Evaluating the psychometric properties of the Mental Health Continuum-Short Form (MHC-SF). J. Clin. Psychol. 2011, 67, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan, L.; Protopopova, A.; Birkler, R.I.D.; Itin-Shwartz, B.; Sutton, G.A.; Gamliel, A.; Yakobson, B.; Raz, T. Human-dog relationships during the COVID-19 pandemic: Booming dog adoption during social isolation. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2020, 7, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, L.; Bennett, P.C. Companion-animals’ effectiveness in managing chronic pain in adult community members. Anthrozoos 2015, 28, 635–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovibond, S.H.; Lovibond, P.F. Manual for the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales, 2nd ed.; Psychology Foundation of Australia: Sydney, Australia, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, C.M.; Treharne, G.J.; Tumilty, S. “All Those Ingredients of the Walk”: The therapeutic spaces of dog-walking for people with long-term health conditions. Anthrozoos 2017, 30, 327–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burn, C.C. A vicious cycle: A cross-sectional study of canine tail-chasing and human responses to it, using a free video-sharing website. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e26553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mills, D.; Luescher, A. Veterinary and pharmacological approaches to abnormal repetitive behaviour. In Stereot Anim Behav Fund Applicat Welfare; CABI: Oxfordshire, UK, 2006; pp. 325–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, P. Situated activities in a dog park: Identity and conflict in human-animal space. Soc. Anim. 2012, 20, 254–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GOV.UK. Mental Health and Loneliness: The Relationship across Life Stages. 2022. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/mental-health-and-loneliness-the-relationship-across-life-stages/mental-health-and-loneliness-the-relationship-across-life-stages (accessed on 29 May 2024).

- Leigh-Hunt, N.; Bagguley, D.; Bash, K.; Turner, V.; Turnbull, S.; Valtorta, N.; Caan, W. An overview of systematic reviews on the public health consequences of social isolation and loneliness. Public Health 2017, 152, 157–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, H.; Loftus, L. Owner psychological characteristics predict dog behavioural traits. Res. Sq. 2023. preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodman, N.H.; Brown, D.C.; Serpell, J.A. Associations between owner personality and psychological status and the prevalence of canine behavior problems. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0192846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, M.; Lourenco, A.; Lima, M.; Serpell, J.; Silva, K. Evaluation of mediating and moderating effects on the relationship between owners’ and dogs’ anxiety: A tool to understand a complex problem. J. Vet. Behav. 2021, 44, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitznagel, M.B.; Cox, M.D.; Jacobson, D.M.; Albers, A.L.; Carlson, M.D. Assessment of caregiver burden and associations with psychosocial function, veterinary service use, and factors related to treatment plan adherence among owners of dogs and cats. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2019, 254, 124–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spitznagel, M.B.; Patrick, K.; Gober, M.W.; Carlson, M.D.; Gardner, M.; Shaw, K.K.; Coe, J.B. Relationships among owner consideration of euthanasia, caregiver burden, and treatment satisfaction in canine osteoarthritis. Vet. J. 2022, 286, 105868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitznagel, M.B.; Solc, M.; Chapman, K.R.; Updegraff, J.; Albers, A.L.; Carlson, M.D. Caregiver burden in the veterinary dermatology client: Comparison to healthy controls and relationship to quality of life. Vet. Dermatol. 2019, 30, 3-e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitznagel, M.B.; Hillier, A.; Gober, M.; Carlson, M.D. Treatment complexity and caregiver burden are linked in owners of dogs with allergic/atopic dermatitis. Vet. Derm. 2021, 32, 192-e50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrios, C.L.; Gornall, V.; Bustos-López, C.; Cirac, R.; Calvo, P. Creation and validation of a tool for evaluating caregiver burnout syndrome in owners of dogs (Canis lupus familiaris) diagnosed with behavior disorders. Animals 2022, 12, 1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarit, S.H.; Reever, K.E.; Bach-Peterson, J. Relatives of the impaired elderly: Correlates of feelings of burden. Gerontologist 1980, 20, 649–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitznagel, M.B.; Jacobson, D.M.; Cox, M.D.; Carlson, M.D. Predicting caregiver burden in general veterinary clients: Contribution of companion animal clinical signs and problem behaviors. Vet. J. 2018, 236, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mills, D.S.; Demontigny-Bédard, I.; Gruen, M.; Klinck, M.P.; McPeake, K.J.; Barcelos, A.M.; Hewison, L.; Van Haevermaet, H.; Denenberg, S.; Hauser, H.; et al. Pain and problem behavior in cats and dogs. Animals 2020, 10, 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitzer, R.L.; Kroenke, K.; Williams, J.B.; Löwe, B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD-7. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006, 166, 1092–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löwe, B.; Kroenke, K.; Herzog, W.; Gräfe, K. Measuring depression outcome with a brief self-report instrument: Sensitivity to change of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9). J. Affect. Disord. 2004, 81, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, A.T.; Ward, C.H.; Mendelson, M.; Mock, J.; Erbaugh, J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1961, 4, 561–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, Y.; Serpell, J.A. Development and validation of a questionnaire for measuring behavior and temperament traits in pet dogs. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2003, 223, 1293–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shoesmith, E.; de Assis, L.S.; Shahab, L.; Ratschen, E.; Toner, P.; Kale, D.; Reeve, C.; Mills, D.S. The perceived impact of the first UK COVID-19 lockdown on companion animal welfare and behaviour: A mixed-method study of associations with owner mental health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCabe, C.J.; Thomas, K.J.; Brazier, J.E.; Coleman, P. Measuring the mental health status of a population: A comparison of the GHQ-12 and the SF-36 (MHI-5). Br. J. Psychiatry 1996, 169, 516–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duffy, D.L.; Kruger, K.; Serpell, J.A. Evaluation of a behavioral assessment tool for dogs relinquished to shelters. Prevent Vet. Med. 2014, 117, 601–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sümegi, Z.; Oláh, K.; Topál, J. Emotional contagion in dogs as measured by change in cognitive task performance. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2014, 160, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, M.H.; Ruffman, T. Emotional contagion: Dogs and humans show a similar physiological response to human infant crying. Behav. Process. 2014, 108, 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunt, M.; Otto, C.M.; Serpell, J.A.; Alvarez, J. Interactions between handler well-being and canine health and behavior in search and rescue teams. Anthrozoös 2012, 25, 323–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiby, E.F.; Rooney, N.J.; Bradshaw, J.W.S. Dog training methods: Their use, effectiveness and interaction with behaviour and welfare. Anim. Welf. 2004, 13, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, N.J.; Brennan, M.L.; Cobb, M.; Dean, R.S. Investigating preventive-medicine consultations in first-opinion small-animal practice in the United Kingdom using direct observation. Prev. Vet. Med. 2016, 124, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mills, D.; Zulch, H. Veterinary assessment of behaviour cases in cats and dogs. In Pract. 2023, 45, 444–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michie, S.; Atkins, L.; West, R. The Behaviour Change Wheel. A Guide to Designing Interventions, 1st ed.; Silverback Publishing: Surrey, UK, 2014; p. 1010. [Google Scholar]

- Marston, L.C.; Bennett, P.C.; Coleman, G.J. Adopting shelter dogs: Owner experiences of the first month post-adoption. Anthrozoös 2005, 18, 358–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephens-Lewis, D.; Johnson, A.; Turley, N.; Naydorf-Hannis, R.; Scurlock-Evans, L.; Schenke, K.C. Understanding canine ‘reactivity’: Species-specific behaviour or human inconvenience? J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci. 2022, 27, 546–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marston, L.C.; Bennett, P.C. Reforging the bond—Towards successful canine adoption. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2003, 83, 227–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shore, E.R.; Burdsal, C.; Douglas, D.K. Pet owners’ views of pet behavior problems and willingness to consult experts for assistance. J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci. 2008, 11, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brand, C.L.; O’Neill, D.G.; Belshaw, Z.; Dale, F.C.; Merritt, B.L.; Clover, K.N.; Tay, M.X.M.; Pegram, C.L.; Packer, R.M. Impacts of puppy early life experiences, puppy-purchasing practices, and owner characteristics on owner-reported problem behaviours in a UK pandemic puppies cohort at 21 months of age. Animals 2024, 14, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson-Schebetta, L. Mythologies and commodifications of dominion in the Dog Whisperer with Cesar Millan. J. Crit. Anim. Stud. 2009, 7, 107–131. [Google Scholar]

- Lyons, N.; Cooper, C.; Lloyd-Evans, B. A systematic review and meta-analysis of group peer support interventions for people experiencing mental health conditions. BMC Psychiatry 2021, 21, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slade, M.; Amering, M.; Farkas, M.; Hamilton, B.; O’Hagan, M.; Panther, G.; Tse, S.; Whitley, R. Uses and abuses of recovery: Implementing recovery-oriented practices in mental health systems. World Psych. 2014, 13, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Health (AU). The Fifth National Mental Health and Suicide Prevention Plan; Department of Health, Commonwealth of Australia: Canberra, Australia, 2017. Available online: https://www.mentalhealthcommission.gov.au/monitoring-and-reporting/fifth-plan (accessed on 29 May 2024).

- Farkas, T.N.; Mendy, J.; Kargas, N. Enhancing resilience in autistic adults using community-based participatory research: A novel HRD intervention in employment service provision. Adv. Dev. Hum. Resour. 2020, 22, 370–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farmer, P.; Dyer, J. The Five Year forward View for Mental Health; The Mental Health Taskforce: London, UK, 2016; Available online: https://www.england.nhs.uk/mental-health/taskforce/ (accessed on 29 May 2024).

- Myrick, K.; Del Vecchio, P. Peer support services in the behavioral healthcare workforce: State of the field. Psychiatr. Rehabil. J. 2016, 39, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnhart, G. Clinical perspectives of adult high-functioning autism support groups’ use of neurodiversity concept. J. Neurol. Neurol. Disord. 2017, 3, 106. [Google Scholar]

- Pantazakos, T.; Vanaken, G.J. Addressing the autism mental health crisis: The potential of phenomenology in neurodiversity-affirming clinical practices. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1225152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellamy, C.; Schmutte, T.; Davidson, L. An update on the growing evidence base for peer support. Ment. Health Soc. Incl. 2017, 21, 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, E.; Pyle, M.; Machin, K.; Varese, F.; Morrison, A.P. The effects of peer support on empowerment, self-efficacy, and internalized stigma: A narrative synthesis and meta-analysis. Stigma Health 2019, 4, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strand, E.; Poe, B.A.; Lyall, S.; Yorke, J.; Nimer, J.; Allen, E.; Brown, G.; Nolen-Pratt, T. Veterinary Social Work Practice in Social Work Fields of Practice: Historical Trends, Professional Issues, and Future Opportunities; Dulmus, C.N., Sowers, K.M., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012; pp. 245–271. [Google Scholar]

- Holcombe, T.M.; Strand, E.B.; Nugent, W.R.; Ng, Z.Y. Veterinary social work: Practice within veterinary settings. J. Hum. Behav. Soc. Environ. 2016, 26, 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compitus, K. The Human-Animal Bond in Clinical Social Work Practice; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Craig, P.; Dieppe, P.; Macintyre, S.; Michie, S.; Nazareth, I.; Petticrew, M. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: The new Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ 2008, 337, a1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bryant, B.K. The richness of the child-pet relationship: A consideration of both benefits and costs of pets to children. Anthrozoös 1990, 3, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poresky, R.H.; Hendrix, C. Differential effects of pet presence and pet-bonding on young children. Psychol. Rep. 1990, 67, 51–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purewal, R.; Christley, R.; Kordas, K.; Joinson, C.; Meints, K.; Gee, N.; Westgarth, C. Companion animals and child/adolescent development: A systematic review of the evidence. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).