Microbiome-Targeted Therapies in Gastrointestinal Diseases: Clinical Evidence and Emerging Innovations

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

3. Established Therapeutic Approaches

3.1. Fecal Microbiota Transplantation Leads to Clinical Efficacy

3.2. Probiotics and Condition-Specific Benefits

3.3. Prebiotics and Synbiotics Expand Therapeutic Options

4. Disease-Specific Clinical Applications

4.1. Inflammatory Bowel Disease Treatment Advances

4.2. Clostridium Difficile Infection Management

4.3. Irritable Bowel Syndrome Symptom Management

4.4. Metabolic Liver Disease Interventions

4.5. Helicobacter Pylori Eradication Enhancement

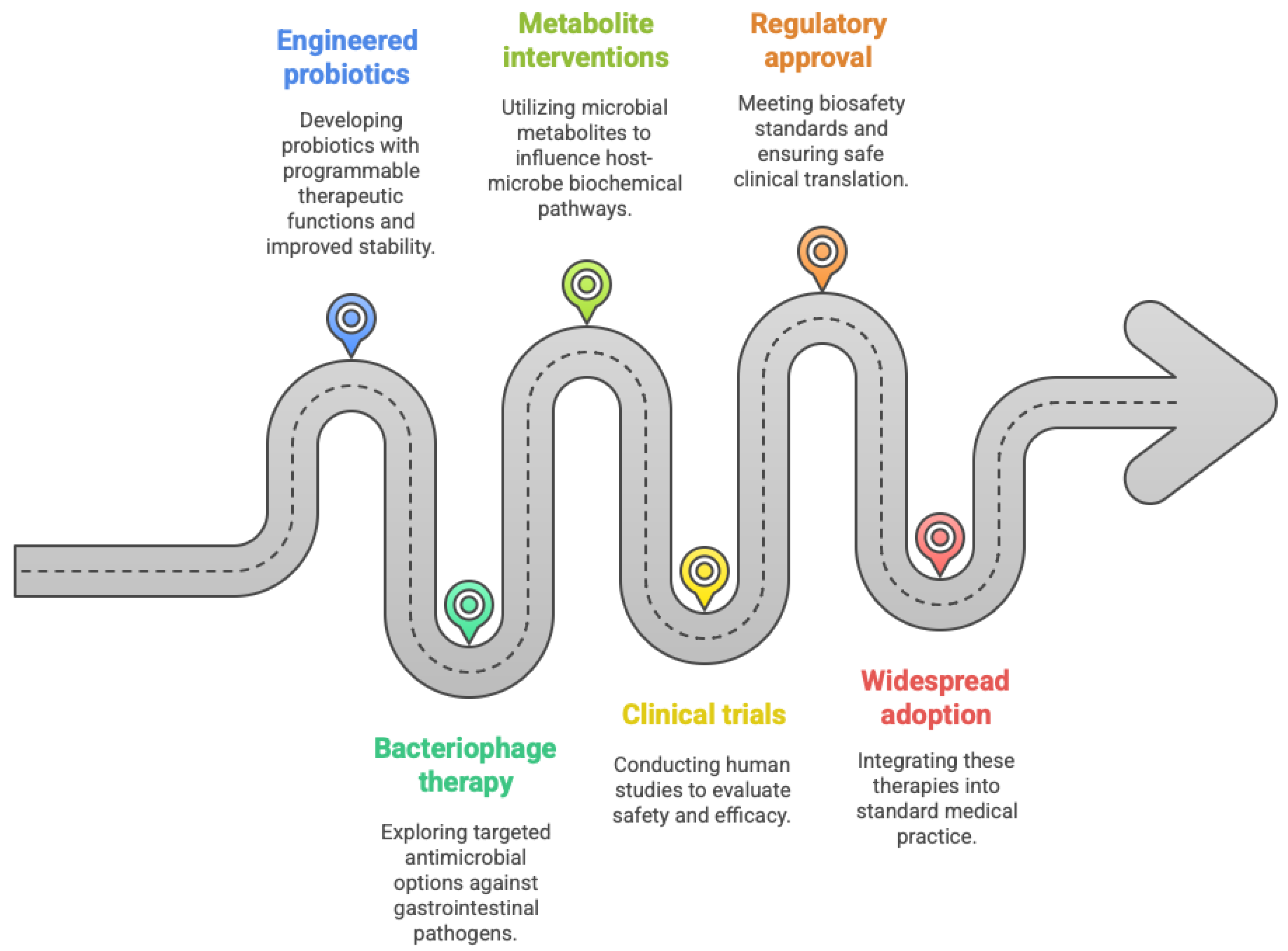

5. Emerging Therapeutic Innovations

5.1. Engineered Probiotics Enter Clinical Development

5.2. Bacteriophage Therapy Development

5.3. Metabolite-Based Interventions Advance

6. Regulatory Landscape and Clinical Implementation

6.1. FDA Approvals Establish Therapeutic Validation

6.2. Cost-Effectiveness Challenges Implementation

6.3. Implementation Barriers Require Systematic Solutions

7. Comparative Effectiveness and Precision Medicine

7.1. Patient Stratification Advances Personalized Approaches

7.2. Long-Term Outcomes Support Sustained Benefits

8. Future Directions and Clinical Implications

8.1. Technological Convergence Drives Innovation

8.2. Regulatory Evolution Supports Innovation

8.3. Market Expansion Drives Investment

9. Clinical Practice Recommendations

9.1. Evidence-Based Implementation Guidelines

9.2. Safety Monitoring Frameworks

10. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AAC | Antibiotic-Associated Colitis |

| ACG | American College of Gastroenterology |

| ACS | American Chemical Society |

| AE | Adverse Event |

| AGA | American Gastroenterological Association |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| ARR | Absolute Risk Reduction |

| ASX | Australian Securities Exchange |

| ATMP | Advanced Therapy Medicinal Product |

| CA | California |

| CBER | Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research |

| CD | Crohn’s Disease |

| CDI | Clostridium difficile Infection |

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus Disease 2019 |

| CRISPR | Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats |

| DOI | Digital Object Identifier |

| EHR | Electronic Health Record |

| EMA | European Medicines Agency |

| EMBASE | Excerpta Medica Database |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration |

| FMT | Fecal Microbiota Transplantation |

| FXR | Farnesoid X Receptor |

| GI | Gastrointestinal |

| GMP | Good Manufacturing Practice |

| HBV | Hepatitis B Virus |

| IBD | Inflammatory Bowel Disease |

| IBS | Irritable Bowel Syndrome |

| ICER | Incremental Cost-Effectiveness Ratio |

| IDSA | Infectious Diseases Society of America |

| III | Phase III Clinical Trial |

| IPO | Initial Public Offering |

| ISAPP | International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics |

| JAMA | Journal of the American Medical Association |

| JB | Journal of Bacteriology |

| LBP | Live Biotherapeutic Product |

| MA | Meta-Analysis |

| MCG | Microgram |

| MD | Doctor of Medicine |

| MIB | Microbiome |

| NAFLD | Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease |

| NASH | Non-Alcoholic Steatohepatitis |

| NNT | Number Needed to Treat |

| PD-1 | Programmed Death-1 |

| PHAGE | Bacteriophage |

| PMID | PubMed Identifier |

| PRIME | Priority Medicines |

| RCT | Randomized Controlled Trial |

| RNA | Ribonucleic Acid |

| SER-109 | Microbiome Therapeutic Product SER-109 |

| SHEA | Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America |

| SSIEM | Society for the Study of Inborn Errors of Metabolism |

| UC | Ulcerative Colitis |

| US | United States |

| USD | United States Dollar |

| VC | Venture Capital |

| VOWST | Microbiome Therapeutic Product Vowst |

| VSL | Probiotic Formulation VSL#3 |

References

- Allegretti, J.R.; Kearney, S.; Li, N.; Bogart, E.; Bullock, K.; Gerber, G.K.; Bry, L.; Clish, C.B.; Alm, E.; Korzenik, J.R. Recurrent C. difficile infection associates with distinct bile acid and microbiome profiles. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2016, 43, 1142–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cammarota, G.; Ianiro, G.; Tilg, H.; Rajilić-Stojanović, M.; Kump, P.; Satokari, R.; Sokol, H.; Arkkila, P.; Pintus, C.; Hart, A.; et al. European consensus conference on faecal microbiota transplantation in clinical practice. Gut 2017, 66, 569–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quraishi, M.N.; Widlak, M.; Bhala, N.; Moore, D.; Price, M.; Sharma, N.; Iqbal, T.H. Systematic review with meta-analysis: The efficacy of faecal microbiota transplantation for the treatment of recurrent and refractory Clostridium difficile infection. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2017, 46, 479–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischer, M.; Kao, D.; Kelly, C.; Kuchipudi, A.; Jafri, S.-M.; Blumenkehl, M.; Rex, D.; Mellow, M.; Kaur, N.; Sokol, H.; et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation is safe and efficacious for recurrent or refractory Clostridium difficile infection in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2016, 22, 2402–2409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feuerstadt, P.; Louie, T.J.; Lashner, B.; Wang, E.E.; Diao, L.; Bryant, J.A.; Sims, M.; Kraft, C.S.; Cohen, S.H.; Berenson, C.S.; et al. SER-109, an oral microbiome therapy for recurrent Clostridioides difficile infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 386, 220–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, C.R.; Fischer, M.; Allegretti, J.R.; LaPlante, K.; Stewart, D.B.; Limketkai, B.N.; Stollman, N.H. ACG clinical guidelines: Prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of Clostridioides difficile infections. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2021, 116, 1124–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Xu, M.; Wang, W.; Cao, X.; Piao, M.; Khan, S.; Yan, F.; Cao, H.; Wang, B.; Grivennikov, S. Systematic review: Adverse events of fecal microbiota transplantation. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0161174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeFilipp, Z.; Bloom, P.P.; Torres Soto, M.; Mansour, M.K.; Sater, M.R.A.; Huntley, M.H.; Turbett, S.; Chung, R.T.; Chen, Y.-B.; Hohmann, E.L. Drug-resistant E. coli bacteremia transmitted by fecal microbiota transplant. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 2043–2050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, A.C.; Harris, L.A.; Lacy, B.E.; Quigley, E.M.M.; Moayyedi, P. Systematic review with meta-analysis: The efficacy of prebiotics, probiotics, synbiotics and antibiotics in irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2018, 48, 1044–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sniffen, J.C.; McFarland, L.V.; Evans, C.T.; Goldstein, E.J.C.; Lobo, L.A. Choosing an appropriate probiotic product for your patient: An evidence-based practical guide. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0209205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derwa, Y.; Gracie, D.J.; Hamlin, P.J.; Ford, A.C. Systematic review with meta-analysis: The efficacy of probiotics in inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2017, 46, 389–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iheozor-Ejiofor, Z.; Kaur, L.; Gordon, M.; Baines, P.A.; Sinopoulou, V.; Akobeng, A.K.; Cochrane IBD Group. Probiotics for maintenance of remission in ulcerative colitis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 3, CD007443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, S.; Stroud, A.M.; Holubar, S.D.; Sandborn, W.J.; Pardi, D.S.; Cochrane IBD Group. Treatment and prevention of pouchitis after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis for chronic ulcerative colitis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 11, CD001176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibson, G.R.; Hutkins, R.; Sanders, M.E.; Prescott, S.L.; Reimer, R.A.; Salminen, S.J.; Scott, K.; Stanton, C.; Swanson, K.S.; Cani, P.D.; et al. Expert consensus document: The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) consensus statement on the definition and scope of prebiotics. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2017, 14, 491–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swanson, K.S.; Gibson, G.R.; Hutkins, R.; Reimer, R.A.; Reid, G.; Verbeke, K.; Scott, K.P.; Holscher, H.D.; Azad, M.B.; Delzenne, N.M.; et al. The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) consensus statement on the definition and scope of synbiotics. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 17, 687–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, G.L.; Ko, C.W.; Bercik, P.; Falck-Ytter, Y.; Sultan, S.; Weizman, A.V.; Morgan, R.L. AGA clinical practice guidelines on the role of probiotics in the management of gastrointestinal disorders. Gastroenterology 2020, 159, 697–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimi, R.; Nikfar, S.; Rahimi, F.; Elahi, B.; Derakhshani, S.; Vafaie, M.; Abdollahi, M. A meta-analysis on the efficacy of probiotics for maintenance of remission and prevention of clinical and endoscopic relapse in Crohn’s disease. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2008, 53, 2524–2531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paramsothy, S.; Kamm, M.A.; Kaakoush, N.O.; Walsh, A.J.; van den Bogaerde, J.; Samuel, D.; Leong, R.W.L.; Connor, S.; Ng, W.; Paramsothy, R.; et al. Multidonor intensive faecal microbiota transplantation for active ulcerative colitis: A randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2017, 389, 1218–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Ding, C.; Gong, J.; Ge, X.; McFarland, L.V.; Gu, L.; Wei, Y.; Chen, Q.; Zhu, W.; Li, J.; et al. Treatment of slow transit constipation with fecal microbiota transplantation: A pilot study. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2016, 50, 865–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldenberg, J.Z.; Yap, C.; Lytvyn, L.; Lo, C.K.-F.; Beardsley, J.; Mertz, D.; Johnston, B.C.; Cochrane IBD Group. Probiotics for the prevention of Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea in adults and children. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 12, CD006095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seres Therapeutics. VOWST Prescribing Information; Seres Therapeutics: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2023; Available online: https://www.vowst.com/prescribing-information (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- Ferring Pharmaceuticals. REBYOTA Monograph. 2025. Available online: https://www.ferring.ca/media/1385/rebyota-pm-control-no-285129-en-mar-5-2025.pdf (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- McDonald, L.C.; Gerding, D.N.; Johnson, S.; Bakken, J.S.; Carroll, K.C.; Coffin, S.E.; Dubberke, E.R.; Garey, K.W.; Gould, C.V.; Kelly, C.; et al. Clinical practice guidelines for Clostridium difficile infection in adults and children: 2017 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA). Clin. Infect. Dis. 2018, 66, e1–e48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dale, H.F.; Rasmussen, S.H.; Asiller, Ö.Ö.; Lied, G.A. Probiotics in irritable bowel syndrome: An up-to-date systematic review. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hungin, A.P.S.; Mulligan, C.; Pot, B.; Whorwell, P.; Agréus, L.; Fracasso, P.; Lionis, C.; Mendive, J.; de Foy, J.-M.P.; Rubin, G.; et al. Systematic review: Probiotics in the management of lower gastrointestinal symptoms in clinical practice—An evidence-based international guide. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2013, 38, 864–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moayyedi, P.; Ford, A.C.; Talley, N.J.; Cremonini, F.; Foxx-Orenstein, A.E.; Brandt, L.J.; Quigley, E.M.M. The efficacy of probiotics in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome: A systematic review. Gut 2010, 59, 325–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newberry, S.J.; Hempel, S.; Maher, A.R.; Wang, Z.; Miles, J.N.V.; Shanman, R.; Johnsen, B.; Shekelle, P.G. Probiotics for the prevention and treatment of antibiotic-associated diarrhea: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2012, 307, 1959–1969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paratore, M.; Santopaolo, F.; Cammarota, G.; Pompili, M.; Gasbarrini, A.; Ponziani, F.R. Fecal Microbiota Transplantation in Patients with HBV Infection or Other Chronic Liver Diseases: Update on Current Knowledge and Future Perspectives. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 2605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nychas, E.; Marfil-Sánchez, A.; Chen, X.; Mirhakkak, M.; Li, H.; Jia, W.; Xu, A.; Nielsen, H.B.; Nieuwdorp, M.; Loomba, R.; et al. Discovery of robust and highly specific microbiome signatures of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Microbiome 2025, 13, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, S.B.; Jun, D.W.; Kang, B.-K.; Lim, J.H.; Lim, S.; Chung, M.-J. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of a multispecies probiotic mixture in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 5688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Pan, Q.; Shen, F.; Cao, H.-X.; Ding, W.-J.; Chen, Y.-W.; Fan, J.-G. Total fecal microbiota transplantation alleviates high-fat diet-induced steatohepatitis in mice via beneficial regulation of gut microbiota. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, H.-R.; Zhang, G.-Q.; Cheng, J.-Y.; Li, Z.-Y. Efficacy of Lactobacillus-supplemented triple therapy for Helicobacter pylori infection in children: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2019, 178, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Huang, X.-L.; Sui, J.-Z.; Chen, S.-Y.; Xie, Y.-T.; Deng, Y.; Wang, J.; Xie, L.; Li, T.-J.; He, Y.; et al. Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials on the efficacy of probiotics in Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy in children. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2014, 173, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, Y.; Reinhardt, J.D.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, G.; Cardona, P.-J. The effect of probiotics supplementation on Helicobacter pylori eradication rates and side effects during eradication therapy: A meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e111030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szajewska, H.; Horvath, A.; Piwowarczyk, A. Meta-analysis: The effects of Saccharomyces boulardii supplementation on Helicobacter pylori eradication rates and side effects during treatment. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2010, 32, 1069–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mimee, M.; Citorik, R.J.; Lu, T.K. Microbiome therapeutics—Advances and challenges. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2016, 105, 44–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riglar, D.T.; Silver, P.A. Engineering bacteria for diagnostic and therapeutic applications. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2018, 16, 214–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claesen, J.; Fischbach, M.A. Synthetic microbes as drug delivery systems. ACS Synth. Biol. 2015, 4, 358–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isabella, V.M.; Ha, B.N.; Castillo, M.J.; Lubkowicz, D.J.; Rowe, S.E.; Millet, Y.A.; Anderson, C.L.; Li, N.; Fisher, A.B.; West, K.A.; et al. Development of a synthetic live bacterial therapeutic for the human metabolic disease phenylketonuria. Nat. Biotechnol. 2018, 36, 857–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Synlogic Inc. A Phase 1/2a Oral Placebo-controlled Study of SYNB1618 in Healthy Adult Volunteers and Subjects with Phenylketonuria, Society for the Study of Inborn Error of Metabolism (SSIEM) 2019, 4 September 2019. Available online: https://investor.synlogictx.com/static-files/e7c256fa-9b6a-47cb-9ef7-7d9cf44d7685 (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- Torres, L.; Krüger, A.; Csibra, E.; Gianni, E.; Pinheiro, V.B. Synthetic biology approaches to biological containment: Pre-emptively tackling potential risks. Essays Biochem. 2016, 60, 393–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Citorik, R.J.; Mimee, M.; Lu, T.K. Sequence-specific antimicrobials using efficiently delivered RNA-guided nucleases. Nat. Biotechnol. 2014, 32, 1141–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brady, T.S.; Fajardo, C.P.; Merrill, B.D.; Hilton, J.A.; Graves, K.A.; Eggett, D.L.; Hope, S. Efficacy of an endolysin against clostridioides difficile assessed in a galleria mellonella infection model. Antibiotics 2018, 7, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, M.J.; Narbad, A.; Gasson, M.J. Molecular characterization of a Clostridium difficile bacteriophage and its cloned biologically active endolysin. J. Bacteriol. 2008, 190, 6734–6740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nale, J.Y.; Spencer, J.; Hargreaves, K.R.; Buckley, A.M.; Trzepiński, P.; Douce, G.R.; Clokie, M.R.J. Bacteriophage combinations significantly reduce Clostridium difficile growth in vitro and proliferation in vivo. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2016, 60, 968–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gindin, M.; Febvre, H.P.; Rao, S.; Wallace, T.C.; Weir, T.L. Bacteriophage for gastrointestinal health (PHAGE) study: Evaluating the safety and tolerability of supplemental bacteriophage consumption. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2019, 38, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.H.; Woolston, J.; Grant-Beurmann, S.; Robinson, C.K.; Bansal, G.; Nkeze, J.; Permala-Booth, J.; Fraser, C.M.; Tennant, S.M.; Shriver, M.C.; et al. Safety and Tolerability of ShigActive™, a Shigella spp. Targeting Bacteriophage Preparation, in a Phase 1 Randomized, Double-Blind, Controlled Clinical Trial. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonçalves, P.; Martel, F. Butyrate and colorectal cancer: The role of butyrate transport. Curr. Drug Metab. 2013, 14, 994–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, A.; De Vadder, F.; Kovatcheva-Datchary, P.; Bäckhed, F. From dietary fiber to host physiology: Short-chain fatty acids as key bacterial metabolites. Cell 2016, 165, 1332–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahlström, A.; Sayin, S.I.; Marschall, H.-U.; Bäckhed, F. Intestinal crosstalk between bile acids and microbiota and its impact on host metabolism. Cell Metab. 2016, 24, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanissery, R.; Winston, J.A.; Theriot, C.M. Inhibition of spore germination, growth, and toxin activity of clinically relevant C. difficile strains by gut microbiota derived secondary bile acids. Anaerobe 2017, 45, 86–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelante, T.; Iannitti, R.G.; Cunha, C.; De Luca, A.; Giovannini, G.; Pieraccini, G.; Zecchi, R.; D’Angelo, C.; Massi-Benedetti, C.; Fallarino, F.; et al. Tryptophan catabolites from microbiota engage aryl hydrocarbon receptor and balance mucosal reactivity via interleukin-22. Immunity 2013, 39, 372–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roager, H.M.; Licht, T.R. Microbial tryptophan catabolites in health and disease. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 3294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cani, P.D.; de Vos, W.M. Next-generation beneficial microbes: The case of Akkermansia muciniphila. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salminen, S.; Collado, M.C.; Endo, A.; Hill, C.; Lebeer, S.; Quigley, E.M.M.; Sanders, M.E.; Shamir, R.; Swann, J.R.; Szajewska, H.; et al. The International Scientific Association of Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) consensus statement on the definition and scope of postbiotics. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 18, 649–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA Approves First Orally Administered Fecal Microbiota Product for the Prevention of Recurrence of Clostridioides Difficile Infection. 2023. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-first-orally-administered-fecal-microbiota-product-prevention-recurrence-clostridioides (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- Mullard, A. FDA approves second microbiome-based C. difficile therapy. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2023, 22, 436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubberke, E.R.; Lee, C.H.; Orenstein, R.; Khanna, S.; Hecht, G.; Gerding, D.N. Results from a randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial of a RBX2660-A microbiota-based drug for the prevention of recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2018, 67, 1198–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGovern, B.H.; Ford, C.B.; Henn, M.R.; Pardi, D.S.; Khanna, S.; Hohmann, E.L.; O’bRien, E.J.; Desjardins, C.A.; Bernardo, P.; Wortman, J.R.; et al. SER-109, an investigational microbiome drug to reduce recurrence after Clostridioides difficile infection: Lessons learned from a phase 2 trial. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021, 72, 2132–2140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for Industry: Early Clinical Trials with Live Biotherapeutic Products. 2016. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/files/vaccines,%20blood%20%26%20biologics/published/Early-Clinical-Trials-With-Live-Biotherapeutic-Products--Chemistry--Manufacturing--and-Control-Information--Guidance-for-Industry.pdf (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- US Food and Drug Administration. Information Pertaining to Additional Safety Protections Regarding Use of Fecal Microbiota for Transplantation. 2020. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/vaccines-blood-biologics/safety-availability-biologics/information-pertaining-additional-safety-protections-regarding-use-fecal-microbiota-transplantation (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- US Food and Drug Administration. Current Good Manufacturing Practice Regulations. 2025. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/pharmaceutical-quality-resources/current-good-manufacturing-practice-cgmp-regulations (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- Institute for Clinical and Economic Review (ICER). Microbiome-Based Therapies for Recurrent Clostridioides Difficile Infection: Effectiveness and Value. 2023. Available online: https://icer.org/assessment/value-assessment-framework-2023 (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- UnitedHealthcare. Medical Policy: Fecal Microbiota Transplantation. 2025. Available online: https://www.uhcprovider.com/content/dam/provider/docs/public/policies/umr/fecal-microbiota-transplantation-umr.pdf (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- Rebiotix Inc. REBYOTA Patient Resources. 2023. Available online: https://www.rebyota.com/rebyota-support-resources/ (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- Nestle HealthScience. VOWST Support Program. 2023. Available online: https://www.vowst.com/savings-and-support (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- Rebiotix Inc. REBYOTA Healthcare Provider Resources. 2022. Available online: https://www.rebyotahcp.com (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- Seres Therapeutics. VOWST Healthcare Provider Resources. 2023. Available online: https://www.vowsthcp.com (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- American Gastroenterological Association. FMT and Other Gut Microbial Therapies National Registry. 2023. Available online: https://gastro.org/research-and-awards/registries-and-studies/fecal-microbiota-transplantation-national-registry/ (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- US Food and Drug Administration. Postmarket Drug Safety Information for Patients and Providers; FDA: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2023. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- Kashyap, P.C.; Chia, N.; Nelson, H.; Segal, E.; Elinav, E. Microbiome at the frontier of personalized medicine. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2017, 92, 1855–1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aron-Wisnewsky, J.; Vigliotti, C.; Witjes, J.; Le, P.; Holleboom, A.G.; Verheij, J.; Nieuwdorp, M.; Clément, K. Gut microbiota and human NAFLD: Disentangling microbial signatures from metabolic phenotypes. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 17, 279–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimentel, M.; Lembo, A.; Chey, W.D.; Zakko, S.; Ringel, Y.; Yu, J.; Mareya, S.M.; Shaw, A.L.; Bortey, E.; Forbes, W.P. Rifaximin therapy for patients with irritable bowel syndrome without constipation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 364, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd-Price, J.; Arze, C.; Ananthakrishnan, A.N.; Schirmer, M.; Avila-Pacheco, J.; Poon, T.W.; Andrews, E.; Ajami, N.J.; Bonham, K.S.; Brislawn, C.J.; et al. Multi-omics of the gut microbial ecosystem in inflammatory bowel diseases. Nature 2019, 569, 655–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francino, M.P. Antibiotics and the human gut microbiome: Dysbioses and accumulation of resistances. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 6, 1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.H.; Steiner, T.; Petrof, E.O.; Smieja, M.; Roscoe, D.; Nematallah, A.; Weese, J.S.; Collins, S.; Moayyedi, P.; Crowther, M.; et al. Frozen vs fresh fecal microbiota transplantation and clinical resolution of diarrhea in patients with recurrent Clostridium difficile infection: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2016, 315, 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischer, M.; Sipe, B.W.; Rogers, N.A.; Cook, G.K.; Robb, B.W.; Vuppalanchi, R.; Rex, D.K. Faecal microbiota transplantation plus selected use of vancomycin for severe-complicated Clostridium difficile infection: Description of a protocol with high success rate. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2015, 42, 470–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baxter, M.; Ahmad, T.; Colville, A.; Sheridan, R. Fatal aspiration pneumonia as a complication of fecal microbiota transplant. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2015, 61, 136–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Topol, E.J. High-performance medicine: The convergence of human and artificial intelligence. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zmora, N.; Soffer, E.; Elinav, E. Transforming medicine with the microbiome. Sci. Transl. Med. 2019, 11, eaaw1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopalakrishnan, V.; Spencer, C.N.; Nezi, L.; Reuben, A.; Andrews, M.C.; Karpinets, T.V.; Prieto, P.A.; Vicente, D.; Hoffman, K.; Wei, S.C.; et al. Gut microbiome modulates response to anti-PD-1 immunotherapy in melanoma patients. Science 2018, 359, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matson, V.; Fessler, J.; Bao, R.; Chongsuwat, T.; Zha, Y.; Alegre, M.-L.; Luke, J.J.; Gajewski, T.F. The commensal microbiome is associated with anti-PD-1 efficacy in metastatic melanoma patients. Science 2018, 359, 104–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Medicines Agency. Reflection Paper on Classification of Advanced Therapy Medicinal Products. 2012. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/regulatory-procedural-guideline/reflection-paper-classification-advanced-therapy-medicinal-products_en.pdf (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- US Food and Drug Administration. Human Gene Therapy for Rare Diseases: Guidance for Industry. 2020. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/human-gene-therapy-rare-diseases (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- US Food and Drug Administration. Breakthrough Therapy. 2018. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/patients/fast-track-breakthrough-therapy-accelerated-approval-priority-review/breakthrough-therapy (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- European Medicines Agency. PRIME: Priority Medicines; EMA: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/human-regulatory/research-development/prime-priority-medicines (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- Grand View Research. Microbiome Therapeutics Market Size, Share and Trends Analysis Report; Grand View Research: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2023; Available online: https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/microbiome-therapeutics-market (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- Ferring Pharmaceuticals. Ferring and PharmaBiome enter into a new microbiome R&D collaboration and exclusive licensing agreement. 2023. Available online: https://www.ferring.com/ferring-and-pharmabiome-enter-into-a-new-microbiome-rd-collaboration-and-exclusive-licensing-agreement/ (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- ASX. Microba Life Sciences Trusts Gut Instinct with IPO. Australian Securities Exchange. 2022. Available online: https://www.asx.com.au/blog/listed-at-asx/microba-life-sciences-trusts-gut-instinct-with-ipo (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- Securities.io. 5 Best Microbiome Companies (August 2025). 2025. Available online: https://www.securities.io/microbiome-companies/ (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- Feldman, R. May Your Drug Price Be Evergreen. J. Law Biosci. 2018, 5, 590–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, S.; Jambert, E.; Childs, M.; von Schoen-Angerer, T. A Win–Win Solution? A Critical Analysis of Tiered Pricing to Improve Access to Medicines in Developing Countries. Glob. Health 2011, 7, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surawicz, C.M.; Brandt, L.J.; Binion, D.G.; Ananthakrishnan, A.N.; Curry, S.R.; Gilligan, P.H.; McFarland, L.V.; Mellow, M.; Zuckerbraun, B.S. Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of Clostridium difficile infections. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2013, 108, 478–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassam, Z.; Lee, C.H.; Yuan, Y.; Hunt, R.H. Fecal microbiota transplantation for Clostridium difficile infection: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2013, 108, 500–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkins, T.; Sequoia, J. Probiotics for gastrointestinal conditions: A summary of the evidence. Am. Fam. Physician 2017, 96, 170–178. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ianiro, G.; Tilg, H.; Gasbarrini, A. Antibiotics as deep modulators of gut microbiota: Between good, bad and ugly. Gut 2016, 65, 1906–1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandt, L.J.; Aroniadis, O.C.; Mellow, M.; Kanatzar, A.; Kelly, C.; Park, T.; Stollman, N.; Rohlke, F.; Surawicz, C. Long-term follow-up of colonoscopic fecal microbiota transplant for recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2012, 107, 1079–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Luo, W.; Shi, Y.; Fan, Z.; Ji, G. Should we standardize the 1700-year-old fecal microbiota transplantation? Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2012, 107, 1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Condition | Intervention | Key Findings | Evidence Strength (GRADE) | Limitations/Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) | Probiotics | AGA: Use only in clinical trials for UC/CD; conditional (very low-certainty) suggestion for 8-strain mix in pouchitis [16]. No significant benefit in Crohn’s remission maintenance [17]. | Very low–low | Benefit limited to specific strains/formulations; remains investigational. |

| FMT (UC) | Multidonor, intensive regimens induced steroid-free remission with endoscopic improvement in ~27% vs. ~8% placebo at 8 weeks [18]. | Moderate | Protocol heterogeneity; optimal regimens unclear. | |

| FMT (Other GI) | Small pilot study in slow transit constipation showed potential benefit [19]. | Very low | Small sample sizes; preliminary data only. | |

| Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) | Probiotics (Primary prevention) | Cochrane review: reduced risk of antibiotic-associated CDI; insufficient data for recurrence prevention [20]. | Moderate | Prevention effect mostly in primary setting. |

| FDA-approved microbiome products | Vowst: recurrence 12.4% vs. 39.8% placebo [21]; Rebyota: success 70.6% vs. 57.5% placebo [22]. | High | Specific to recurrent CDI; long-term durability still being studied. | |

| FMT | Recommended by IDSA/SHEA for multiply recurrent CDI after antibiotic failure [23]. | High | Requires donor screening; procedural infrastructure needed. | |

| Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS) | Probiotics | Multi-strain > single strain for symptom improvement; e.g., B. infantis 35624 effective for global symptoms/abdominal pain [24,25]. | Low–Moderate | Strain-specific effects; optimal dose/duration unclear. |

| Treatment duration | ≥8 weeks associated with better outcomes [26]. | Short courses less effective. | ||

| Safety | No increased adverse events vs. placebo in large GI meta-analyses [27]. | High | Well-tolerated across trials. | |

| Metabolic Liver Disease (NAFLD/NASH) | Probiotics | Some RCTs show improvements in liver enzymes, steatosis, inflammatory markers [28,30]. | Low–Moderate | Meta-analytic confirmation lacking. |

| FMT | Early pilot data suggest benefit; animal models support potential [29,31]. | Very low | Human translation at early stage. | |

| Helicobacter pylori | Probiotic adjuncts to eradication therapy | Modest increase in eradication rates; reduced antibiotic-associated diarrhoea [34,35]. | Moderate | Effects strain- and regimen-dependent. |

| Strains studied | Lactobacillus spp., S. boulardii most consistent; paediatric triple therapy with Lactobacillus improved outcomes [32,33]. | No clear strain superiority established. |

| Condition | Intervention | Sample Size/Follow-Up | Evidence Source | Evidence Strength (GRADE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recurrent CDI | FMT (various delivery routes) | RCTs: 40–232 patients; 8–12 weeks follow-up [3] | RCTs + Meta-analysis | High |

| Vowst (SER-109) | Phase 3 RCT: 182 patients; 8 weeks [5] | Regulatory trial (FDA submission) | High | |

| Rebyota (RBX2660) | Phase 3 RCTs + pooled analysis: ~270 patients; 8 weeks [22] | Regulatory trial + integrated analyses | High | |

| Ulcerative colitis | Multidonor intensive FMT | RCT: 81 patients; 8 weeks [18] | RCT | Moderate |

| Inflammatory Bowel Disease | Probiotics (VSL#3/multi-strain) | Trials 50–200 patients; 8–52 weeks [16,17] | RCTs + Cochrane reviews | Low–very low |

| Probiotics (various strains) | Trials 80–400 patients; 4–12 weeks [9,24] | RCTs + Systematic reviews | Low–moderate | |

| H. pylori eradication | Adjunct probiotics (Bifidobacterium-based) | RCTs ~200 patients; 4–8 weeks [30] | RCTs | Low–moderate |

| Therapy | Condition | Best-Supported Outcome | Effect vs. Control | Approx NNT | Evidence Quality | Key Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FMT | Recurrent CDI | Clinical cure/recurrence prevention | Substantially higher cure vs. antibiotics; high effectiveness in recurrent/refractory CDI | Moderate (mixed RCT/obs.) | Strong benefit across studies, but heterogeneity precludes a single pooled “success %” [3]. | |

| Multi-strain probiotics | UC maintenance | Maintenance of remission | Evidence uncertain; no robust pooled benefit | Low–very low | Cochrane review could not confirm routine benefit for UC maintenance [12]. | |

| Vowst (SER-109) | Recurrent CDI | Recurrence at 8 weeks | 12.4% vs. 39.8% recurrence (absolute ↓ 27.4%) | ~4 | High (Phase 3 RCT) | Oral capsules × 3 days; FDA-approved microbiota product [59]. |

| Rebyota (RBX2660) | Recurrent CDI | Treatment success at 8 weeks | 70.6% vs. 57.5% success (absolute ↑ 13.1%) | ~8 | High (integrated licensure analyses + RCTs) | Single-dose rectal administration; FDA-approved [58]. |

| Bifidobacterium-containing probiotics (adjunct) | H. pylori eradication | Eradication rate; adverse effects | Modest increase in eradication and reduced AEs (strain/regimen dependent) | Low–moderate | Benefits are small and strain-specific; strongest data are mixed-probiotic or S. boulardii analyses [32,33,34,35]. | |

| VSL#3 (multi-strain) | UC induction/maintenance | Clinical remission/maintenance | Signals of benefit in UC in some analyses; heterogeneity limits precision | Low–moderate | Effect sizes vary by study; dosing/optimal use not firmly established [11]. |

| Theme | Key Developments | Clinical/Commercial Implications | Evidence or Market Indicators | Limitations/Gaps |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Technological convergence | AI + -omics integration for precision treatment selection (↑) [79] | Supports personalized microbiome therapy; aligns with AI-enabled decision-making in medicine | AI models analyse high-dimensional clinical & microbiome data; early success in oncology | Prospective validation needed; risk of overfitting in small datasets |

| Standardisation of defined microbial consortia manufacturing (↑) [80] | Improves reproducibility, quality, and safety of therapeutics | GMP-aligned processes emerging; regulatory interest in consistency | High cost of compliance; technical complexity | |

| Longitudinal monitoring via next-generation sequencing (↑) [80] | Enables dynamic tracking of microbiome composition & host response | Used in research; potential in clinical follow-up | Cost, data interpretation challenges | |

| Gut microbiome linked to anti-PD-1 immunotherapy response in melanoma (↑) [81,82] | Potential for microbiome-informed combination oncology regimens | Multiple studies show associations; rationale for interventional trials | Causality unproven; effect on toxicity unclear | |

| Regulatory evolution | EMA ATMP reflection paper & FDA gene therapy guidance [83,84] | Provide frameworks for novel biologics, adaptable to microbiome products | Clarify product categories, manufacturing, and safety expectations | Not microbiome-specific; interpretation may vary |

| FDA Live Biotherapeutic Product (LBP) designation | Streamlines regulatory classification and review | Recognised pathway for microbiome-based products | Requires detailed manufacturing and clinical data | |

| Expedited pathways: FDA Breakthrough Therapy & EMA PRIME (↑) [85,86] | Accelerate development of promising microbiome therapeutics | Offer enhanced scientific/regulatory support | Reserved for high-impact products; stringent entry criteria | |

| Market expansion | Global market projected USD 300M (2021) → USD 3.2B (2032) (↑) [87] | Demonstrates rapid sector growth potential | CAGR driven by approvals, validation, and adoption | Projections depend on regulatory success |

| Pharma–biotech strategic collaborations (↑) [88] | Accelerate product development through shared expertise | Examples in manufacturing scale-up and trial execution | Risk of dependency on single large partners | |

| Public market example: Microba Life Sciences IPO on ASX (↑) [89] | Signals investor confidence; sector valued at USD 4.89B | Increased visibility for microbiome companies | Market volatility risk | |

| Private market: >USD 1.6B VC funding in 2 years (↑) [90] | Sustained investor interest despite hurdles | Supports pipeline diversification | Funding concentrated in select markets | |

| Patent & IP strategies [91,92] | Secure market exclusivity post-approval; promote access via tiered licensing/pools | Shapes competitive landscape; encourages innovation | Tension between exclusivity & equitable access |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Hellenic Society for Microbiology. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lim, E.C.N.; Lim, C.E.D. Microbiome-Targeted Therapies in Gastrointestinal Diseases: Clinical Evidence and Emerging Innovations. Acta Microbiol. Hell. 2025, 70, 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/amh70030036

Lim ECN, Lim CED. Microbiome-Targeted Therapies in Gastrointestinal Diseases: Clinical Evidence and Emerging Innovations. Acta Microbiologica Hellenica. 2025; 70(3):36. https://doi.org/10.3390/amh70030036

Chicago/Turabian StyleLim, Enoch Chi Ngai, and Chi Eung Danforn Lim. 2025. "Microbiome-Targeted Therapies in Gastrointestinal Diseases: Clinical Evidence and Emerging Innovations" Acta Microbiologica Hellenica 70, no. 3: 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/amh70030036

APA StyleLim, E. C. N., & Lim, C. E. D. (2025). Microbiome-Targeted Therapies in Gastrointestinal Diseases: Clinical Evidence and Emerging Innovations. Acta Microbiologica Hellenica, 70(3), 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/amh70030036