Abstract

Background: Brain computed tomography (CT) is the primary imaging modality for patients with acute neurological complaints in emergency departments, despite having a low diagnostic yield for many conditions. This study aimed to assess the common indications for brain CT, evaluate the prevalence of acute pathologies, and explore whether certain patient groups may be overexposed to unnecessary scans, impacting both patient safety and healthcare costs. Methods: We conducted a retrospective review of brain CT requests from the General Emergency Department in a single center over a one-month period. We recorded patient demographics (sex, age), scan indications, presence of focal neurological symptoms, acute pathology on CT, and final diagnoses. Descriptive statistics, including means ± SEM, were calculated using GraphPad Prism version 10.4.1. Results: A total of 584 brain CT scans were requested, of which 532 (91.1%) were normal, and 52 (8.9%) showed acute pathology. The age of all included patients were 70.8 ± 0.7 years with women (n = 304, 52.1%) being 71.9 ± 1.0 years old and men (n = 280, 47.9%) 69.7 ± 1.0 years old (p > 0.1). The most common indication for CT was head trauma (265, 45.4%) followed by ischemic stroke (130, 22.3%). The most frequent pathologies were ischemic stroke (2.7%), subdural hematoma (1.7%), and other traumatic bleeds (1.7%). Of the 52 patients with acute pathology, 42 (80.8%) exhibited focal neurological deficits. Conclusions: 91.1% of the brain CT scans in the emergency department were normal and did not lead to further intervention. While this may indicate a low diagnostic yield in certain patient groups—particularly those presenting with mild or nonspecific neurological symptoms—it does not alone confirm overuse. These findings highlight the importance of careful clinical evaluation to optimize imaging decisions. Reducing potentially unnecessary brain CT scans could lower healthcare costs and minimize radiation exposure, but the health-economic impact depends on balancing the savings with the potential costs of missing critical diagnoses and the associated societal consequences.

1. Introduction

Brain CT has become the primary imaging modality for patients with acute neurological complaints in emergency departments worldwide. It is quick, easily accessible, and involves a relatively low effective dose of ionizing radiation compared to, for example, CT of the abdomen. Indications for brain CT vary widely and include stroke, head trauma, dizziness, seizures, and headaches. In the emergency setting, brain CT is often performed to rapidly exclude hemorrhage, enabling timely initiation of appropriate treatment. While brain CT is effective at identifying hemorrhages or major structural abnormalities, its diagnostic yield is limited for certain conditions, particularly ischemic stroke and non-specific symptoms such as monosymptomatic dizziness.

Despite its limitations, the use of brain CT continues to rise. In patients presenting with acute dizziness for example, the diagnostic yield is only 2.2% [1]. Contributing factors may include physician concerns about missing serious pathology, patient expectations, and the influence of defensive medicine, which has been increasing since the 1960s [2,3]. This trend raises concerns about the potential overutilization of CT imaging, which may lead to unnecessary radiation exposure, increased healthcare costs, and strain on emergency department resources. However, data on the appropriateness and diagnostic yield of brain CT in different clinical contexts remain limited.

The high volume of brain CT scans performed at North Zealand Hospital General Emergency Department served as the initial motivation for this study. Approximately 600 brain CT scans are requested each month—around 20 per day—out of a daily patient population of around 250, meaning that 8.0% of patients undergo brain CT scanning daily. Therefore, the aim of this study was to assess the common indications for brain CT, evaluate the prevalence of acute pathology identified, and explore whether certain patient groups might be overexposed to unnecessary imaging while balancing diagnostic benefit, patient safety, and resource utilization.

2. Materials and Methods

This retrospective, observational, and descriptive study was conducted in a single center emergency department over a one-month period (October 2024).

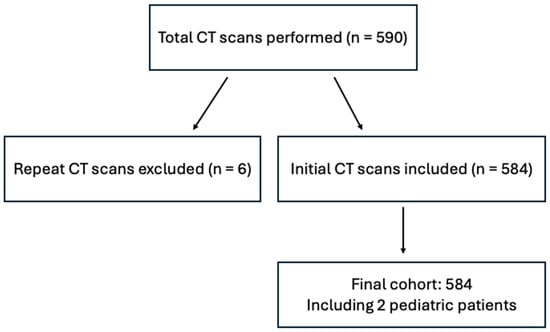

Brain CT scans performed at the General Emergency Department of North Zealand Hospital between 1 October 2024 and 31 October 2024 were retrospectively reviewed. Inclusion criteria comprised all patients who underwent an initial brain CT scan during their visit. Repeat CT scans during the same episode of care were excluded; however, the initial scan for these patients was included. In total, 590 brain CT scans were performed. After excluding 6 repeat scans, 584 unique initial CT scans were included in the analysis. All brain CT were reported by a radiologist and reevaluated during radiology conferences. Patients with suspected ischemic stroke who presented themselves at North Zealand Hospital were evaluated primarily by emergency physicians and upon consultation with neurologists on call.

The study population consisted primarily of adult patients; however, two pediatric patients (under 18 years) who were treated in the general emergency department were also included. Most pediatric patients are managed in a separate Pediatric Emergency Department and were therefore not part of this dataset. A flowchart depicting the study cohort and exclusions is provided in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Study cohort flowchart.

Data collected included patient demographics (age, sex), clinical indication for the scan, presence of focal neurological symptoms, acute pathology identified on CT (defined as findings requiring medical intervention, including cranial fractures without associated brain injury), and final diagnosis. CT scan indications were determined based on imaging referrals and medical records. Imaging findings from modalities other than CT, such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), were not included. There were no missing data for the key variables analyzed.

Descriptive statistics were calculated for the total population and each gender subgroup (women and men). Values are presented as means ± SEM. A Student’s t-test for unpaired samples was used to compare the average ages between women and men. Statistical significance was accepted at p-values < 0.05. All analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism.

3. Results

The age of all included patients (n = 584) were 70.8 ± 0.7 years with women (n = 304, 52.1%) being 71.9 ± 1.0 years old and men (n = 280, 47.9%) 69.7 ± 1.0 years old (p > 0.1). Study sample characteristics are seen in Table 1. The most common indication for brain CT was head trauma, followed by ischemic stroke. Other indications included dizziness, headache, confusion, and more (see Table 2).

Table 1.

Study sample characteristics.

Table 2.

Indications and pathology.

The indications for CT scans, as presented in Table 2, are based on the documentation provided by the attending physician in the CT request form and medical record. These indications include a mix of presenting symptoms (e.g., headache, dizziness), clinical impressions, and suspected diagnoses (e.g., stroke, transient ischemic attack), reflecting the real-world variability in how such requests are documented in emergency settings. This approach was chosen to preserve the authenticity of physician documentation and reflects typical clinical practice where initial working diagnoses are often recorded based on available clinical information. To standardize assessment of physical findings, patients were categorized based on the presence or absence of focal neurological deficits as noted in the medical record.

3.1. CT Scan Findings and Neurological Deficits

Of the 584 scans, 532 (91.1%) were normal, while 52 (8.9%) showed acute pathology. The most common findings were ischemic stroke in 16 cases (2.7%), subdural hematoma (SDH) in 10 cases (1.7%), and various combinations of traumatic bleeds (e.g., traumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage (t-SAH) and SDH) in 10 cases (1.7%) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Diagnoses on CT.

Of the 52 patients with acute pathology, 41 exhibited focal neurological deficits and one had explosive vomiting. This means that 42 out of 52 (80.8%) patients had symptoms indicative of CNS pathology. Of all the patients, 99 (17.0%) had focal neurological deficits but no pathology on CT.

3.2. Head Trauma

Head trauma was the leading indication for brain CT, with 265 patients (45.4%). Of these, 24 (9.1%) had acute pathology on CT, with 7 showing cranial fractures without brain injury (see Table 4). Acute findings included t-SDH, t-SAH, and traumatic intracranial hemorrhage (t-ICH), in various combinations. 14 of the 24 patients with pathology on their scan exhibited neurological deficits. CT scans for head trauma adhered to the guidelines set by the Scandinavian Neurotrauma Committee, considering factors like GCS, age, focal neurological deficits, loss of consciousness, vomiting, and anticoagulant use. These guidelines are prominently displayed in the emergency department and serve as the standard protocol for clinicians when determining the need for brain CT in trauma cases.

Table 4.

Indication and radiological findings.

3.3. Ischemic Stroke

Ischemic stroke was another common indication with 130 patients (22.3%). Of these, 12 (10.8%) showed infarction and 2 revealed spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage (see Table 4). 16 (2.7%) out of all patients in this study had infarction on their CT scan. All the patients with ischemic stroke on their CT scan had focal neurological deficits indicating that the brain CT was more likely to be positive in patients who presented with deficits. Additionally, 12 patients were scanned for suspected transient ischemic attack (TIA) and no focal neurological deficits, but none showed acute pathology.

3.4. Dizziness, Confusion, and Headache

Twenty-nine patients (5.0%) were scanned due to dizziness. Two had focal neurological deficits, and one of these had acute pathology on CT (infarction). The rest of the patients had monosymptomatic dizziness and had no pathology on CT.

Twenty-eight (4.8%) patients underwent brain CT scans due to confusion, and one had acute pathology (infarction) while the rest had no pathology on CT. This patient was the only one with confusion combined with focal neurological deficits. It should be noted that there is some overlap between confusion and altered mental behavior. The indication for the scan was determined based on the clinicians’ wording in the referral and journal entry. Interestingly, the prevalence of pathology was higher in patients with altered mental behavior than in those with confusion, as shown in Table 2.

Twenty-two (3.8%) patients presented with headache (type unspecified). One had acute pathology (sagging brain), and this patient was the only one with focal neurological deficits. Sagging brain is rare and can be due to intracranial hypotension, leading to a downward displacement of the brain known as “brain sag”.

It is interesting that the indications dizziness, confusion, and headache had a low rate of focal neurological deficits and only one scan with acute pathology in each indication group.

4. Discussion

This study aims to evaluate the common indications for brain CT in the emergency department and the prevalence of acute findings and discuss the potential overuse of imaging in certain patient groups. The most significant result in this study is that more than 90% the brain CT scans were normal. This prevalence of acute pathology is lower than what has been observed in other studies. For example, a similar study conducted in an emergency center over two months, involving 578 scans, found that 80% of CT scans were normal [4]. Another study from a Spanish emergency department, reviewing 507 brain CT scans over two months, found that 43.2% of scans were normal [5]. It is important to note that this study included CT angiography and perfusion CT as part of their stroke protocol, which likely increased the sensitivity of CT in detecting pathology. Furthermore, they included soft tissue hematoma and chronic infarctions as acute findings on CT, whereas we did not. The most common abnormal finding was ischemic lesions, and the most frequent indication was head trauma, which aligns with our results.

Head trauma was the most common indication in our study, although only 9.1% of these scans revealed acute pathology. A large-scale study with external validation investigated brain CT pathology after mild traumatic brain injury (TBI) and found that approximately 60% of the brain CT showed no acute pathology [6]. The lower yield in this study may reflect different institutional practices. Another study that examined clinical criteria for brain CT in patients with mild to moderate traumatic brain injury found that 16.5% of the 610 patients had positive CT findings, with the highest percentage linked to high-energy trauma mechanisms [7]. Pathology was more likely in patients with additional symptoms, such as decreased consciousness, severe headache, or skull fracture [7]. A different study examining the relevance of brain CT in elderly patients who fell from their own height found that only 38 out of 500 patients (7.6%) had traumatic lesions on their scans. Post-traumatic injury was significantly associated with impaired consciousness, focal neurological deficits, a history of previous brain injury, and male sex [8]. Our study similarly found a 9.1% prevalence of pathology, with 14 of the 24 patients exhibiting neurological deficits. Although we assume that clinicians followed the Scandinavian Neurotrauma Committee guidelines, as they are the recommended protocol and clearly displayed in the emergency department, individual adherence was not systematically assessed in this retrospective study.

The diagnostic yield across different clinical indication groups is of interest and may benefit from further investigation. The highest proportion of acute pathology on brain CT was observed in patients with altered mental status and suspected hemorrhagic stroke. However, these subgroups were significantly smaller than the head trauma and suspected infarction groups, making it difficult to draw firm conclusions based on the current data. In contrast, the subgroups for dizziness, seizures, confusion, and headache showed a low rate of acute findings (0–5%), with each group including an average of 22–36 patients. Notably, only one or two patients in each of these subgroups presented with focal neurological deficits—and these were the only cases with acute pathology on CT. Dizziness is a frequent complaint in emergency departments, often presenting a diagnostic challenge due to its many potential causes, including neurological, vestibular, or cerebrovascular disorders. Especially posterior stroke is a diagnosis clinicians do not want to miss. A retrospective study found that 93.1% of brain scans requested for dizziness were normal, particularly in patients without neurological deficits [9]. Another study identified three factors that significantly correlated with pathology on brain CT in patients with dizziness or syncope: focal neurological deficits, age over 60, and recent acute head trauma [10]. Our findings are consistent with these results, as all patients with dizziness but no neurological deficits had normal CT scans.

Across all indication subgroups, the CTs were more likely to be positive in patients with neurological deficits. 42 out of the 52 scans with acute pathology on CT were in patients with focal neurological deficits. However, focal neurological deficits were also present in 17.0% of the patients in this study with no pathology on CT. This raises the question of whether the lack of findings is due to the limitations of the CT modality itself or the absence of neurological pathology. One limitation of this study is that we do not know if other imaging modalities, such as brain MRI or CT angiography, were used to identify pathology. Given that CT may have a higher risk of false negatives, one could argue that it does not make sense to use this as the first line imaging modality in stroke. On the other hand, neurologists argue that it is crucial to rule out hemorrhage in stroke before initiating antiplatelet therapy while awaiting MRI results. Additionally, brain CT can provide valuable information in stroke diagnosis, such as early ischemic changes, chronic infarcts, or the hyperdense artery sign, which can aid in guiding subsequent treatment [11]. The lack of data on subsequent clinical management in this study limits the ability to judge the appropriateness of CT use in individual cases.

Another potential limitation of this study is its relatively short duration (one month) and single center design, which may limit the ability to generalize the findings to a broader population. Additionally, since North Zealand Hospital is not a designated stroke code referral center, the number of patients with acute infarction may be lower, which could influence the representativeness of the results.

Defensive medicine, characterized by excessive and often unnecessary diagnostic testing to protect physicians from potential legal claims, has become increasingly common in recent years [3,12]. The growing use of brain CT scans in emergency departments may reflect his practice. While such overutilization can lead to unnecessary radiation exposure, increased healthcare costs, and low diagnostic yield in certain patient groups, it is important to acknowledge that a negative brain CT scan can still hold significant clinical value. In emergency settings, a normal CT can help rule out life-threatening conditions such as hemorrhage or mass effect, guide decisions about admission versus discharge, and reduce the need for further imaging. Thus, the absence of acute findings does not imply that the scan lacked clinical utility; rather, it may have played an important role in patient assessment and management, particularly when neurological symptoms or concerns were present. It may be surmised that reducing the number of low-yield CT scans would lower resource use and free up scanner capacity and radiologist time for more urgent cases. However, it is not feasible to provide data to this extent in a Danish health care setting, because everyone who has been granted a residence permit and lives in Denmark has tax paid free access to the healthcare system, and common examinations and treatments are free of charge individually [13].

Given the retrospective and single-center nature of this study, the results should be interpreted with some caution. Larger, multicenter or longitudinal studies would help validate these findings across diverse clinical settings, assess adherence to imaging guidelines more systematically, and better evaluate the balance between diagnostic yield and clinical utility in emergency brain CT use. While the impact of CT findings on subsequent clinical management was beyond the scope of this analysis, it is an important area that we aim to explore in future research.

5. Conclusions

This study found that 91.1% of brain CT scans in the emergency department were normal, with 8.9% showing acute pathology. The most common reasons for scans were head trauma and ischemic stroke. This likely reflects the role of brain CT in ruling out serious conditions in emergency settings. Drawing firm conclusions about possible overuse and post-CT clinical decision-making would require a longer study period and a more extensive dataset.

Reducing unnecessary brain CT scans could lower healthcare costs and minimize radiation exposure without compromising diagnostic accuracy. However, the health-economic impact of fewer scans depends on balancing the potential costs of missing critical diagnoses—leading to significant societal consequences and human suffering—against the savings from reducing the number of scans. This balance requires further analysis. A more selective approach, guided by clinical judgment and tailored to individual patient symptoms, is essential for enhancing patient safety and improving the efficiency of emergency care.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ecm2030044/s1, Approval of quality project.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.M.L. and T.A.S.; methodology, A.M.L.; software, A.M.L. and T.A.S.; validation, T.A.S. and J.J.L.; formal analysis, A.M.L.; investigation, A.M.L.; resources, J.J.L.; data curation, J.J.L.; writing—original draft preparation, A.M.L.; writing—review and editing, T.A.S.; visualization, A.M.L.; supervision, T.A.S. and J.J.L.; project administration, A.M.L. and T.A.S.; funding acquisition: no funding was acquired. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data access was granted by the Institutional Review Bord (IRB) of North Zealand Hospital to assess departmental health care quality. Head of quality assurance and patient safety at North Zealand Hospital, Karen Gliese Nielsen, approved the project on behalf of the IRB, her signature is attached in supplementary files. The reference number for this project is: 25000839. The data for this article was processed in an anonymized fashion.

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived due to the Institutional Review Board at North Zealand Hospital deemed the need for patients’ consent to participate in the current study unnecessary, because the CT scan data were processed anonymously, and the scope was to assess departmental health care quality. The aggregated quality data may subsequently be freely used for further research. This is in accord with the Danish Health Care Act (dk: Sundhedsloven) (https://www.retsinformation.dk/eli/lta/2024/247, accessed on 10 May 2025).

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the Radiology Department for their valuable contribution in reviewing and describing all the brain CT scans included in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CT | Computed tomography |

| t-SAH | Subarachnoid hemorrhage |

| t-SDH | Traumatic subdural hematoma |

| t-ICH | Traumatic intracranial hemorrhage |

| TGA | Transient global amnesia |

| TIA | Transient ischemic attack |

| MRI | Magnetic resonance imaging |

References

- Lawhn-Heath, C.; Buckle, C.; Christoforidis, G.; Straus, C. Utility of head CT in the evaluation of vertigo/dizziness in the emergency department. Emerg. Radiol. 2013, 20, 45–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alimohammadi, H.; Zareh Shahamati, S.; Karkhaneh Yousefi, A.; Safarpour Lima, B. Potentially inappropriate brain CT-scan requesting in the emergency department: A retrospective study in patients with neurologic complaints. Acta Bio-Medica Atenei Parm. 2021, 92, e2021302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berlin, L. Medical errors, malpractice, and defensive medicine: An ill-fated triad. Diagnosis 2017, 4, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emergency Head CT Scan ¿Is It Indicated? Available online: https://epos.myesr.org/poster/esr/ecr2017/C-1887 (accessed on 9 March 2025).

- Novoa Ferro, M.; Santos Armentia, E.; Silva Priegue, N.; Jurado Basildo, C.; Sepúlveda Villegas, C.A.; Del Campo Estepar, S. Brain CT requests from emergency department: Reality. Radiologia 2022, 64, 422–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuh, E.L.; Jain, S.; Sun, X.; Pisică, D.; Harris, M.H.; Taylor, S.R.; Markowitz, A.J.; Mukherjee, P.; Verheyden, J.; Giacino, J.T.; et al. Pathological Computed Tomography Features Associated with Adverse Outcomes After Mild Traumatic Brain Injury: A TRACK-TBI Study with External Validation in CENTER-TBI. JAMA Neurol. 2021, 78, 1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molaei-Langroudi, R.; Alizadeh, A.; Kazemnejad-Leili, E.; Monsef-Kasmaie, V.; Moshirian, S.-Y. Evaluation of Clinical Criteria for Performing Brain CT-Scan in Patients with Mild Traumatic Brain Injury; A New Diagnostic Probe. Bull. Emerg. Trauma 2019, 7, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pages, P.-J.; Boncoeur-Martel, M.-P.; Dalmay, F.; Salle, H.; Caire, F.; Mounayer, C.; Rouchaud, A. Relevance of emergency head CT scan for fall in the elderly person. J. Neuroradiol. 2020, 47, 54–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masood, A.; Alkhaja, O.; Alsetrawi, A.; Alshaibani, F.; Awad, A.; Habbash, Z.; Alyusuf, Z.Y.; Ali, N.; Al Mail, S.; Al Taei, T. The Diagnostic Value of Brain CT Scans in Evaluating Dizziness in the Emergency Department: A Retrospective Study. Cureus 2024, 16, e52483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitsunaga, M.M.; Yoon, H.-C. Journal Club: Head CT scans in the emergency department for syncope and dizziness. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2015, 204, 24–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czap, A.L.; Sheth, S.A. Overview of Imaging Modalities in Stroke. Neurology 2021, 97, S42–S51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pischedda, G.; Marinò, L.; Corsi, K. Defensive medicine through the lens of the managerial perspective: A literature review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2023, 23, 1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Danish Healthcare System. Available online: http://www.sst.dk/en/english/publications/2017/The-Danish-healthcare-system (accessed on 30 July 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).