1. Introduction

Between 1 and 8% of pediatric abdominal pain presenting to emergency care is estimated to be due to acute appendicitis [

1]. Appendicitis is the most common surgical pathology in children, with an annual incidence of 83 per 100,000. In the United States, one-fifth of pediatric hospitalizations are for treatment of appendicitis. In 2018, there were 40,000 hospitalizations for pediatric appendectomy, at a cost of USD 492 million [

2].

Development of appendicitis is generally attributed to luminal obstruction of the appendix by enlarged lymph nodes, a fecalith, or impacted stool, although several infectious etiologies are associated with appendicitis [

3]. Obstruction increases intraluminal pressure, which can then cause vascular compromise, mucosal ischemia, and bacterial translocation through the appendiceal wall. Appendicitis can occur without evidence of luminal obstruction, and some suggest that secondary bacterial invasion of the appendix after gastrointestinal illness can cause acute appendicitis [

2]. However, the exact pathogenesis of pediatric appendicitis remains unclear. Children with appendicitis generally present with abdominal pain that begins periumbilically and migrates to the right lower quadrant. They often have nausea, anorexia, and emesis, with fever a less frequent symptom. Physical examination maneuvers eliciting the psoas, Rovsing, and obturator signs have low sensitivities of between 16% and 44% [

2], and risk-stratification rules such as the Pediatric Appendicitis Score, The Appendicitis Inflammatory Response score, and the pediatric Appendicitis Risk Calculator have been developed to aid in diagnostic precision [

4,

5,

6]. Ultrasound is a first-line imaging study to evaluate for appendicitis [

7], although computed tomography (CT) continues to be a frequently used imaging modality [

8]. While surgery has traditionally been the preferred treatment for appendicitis in both adults and children, conservative (nonsurgical) therapy has become more acceptable, although results from a meta-analysis indicate that 18% of children treated successfully with conservative therapy proceed ultimately to appendectomy [

1].

The literature has suggested that there are two variants of appendicitis: a simple variant that may even resolve spontaneously and a more aggressive variant that may proceed to complication [

9,

10]. Interestingly, a trial of conservative therapy for uncomplicated pediatric appendicitis noted that none of the children treated conservatively presented with complicated appendicitis [

11]. There is little evidence, however, supporting the existence of distinct forms of appendicitis. The scoring systems noted above assign weight to elevated inflammatory markers [

12]. Here, we present a study of two distinct populations that might be described as having “mild” appendicitis: children with appendicitis presenting with normal inflammatory markers (NIMs) and confirmed with pathologic examination, and children with sonographically confirmed appendicitis that resolved without medical or surgical intervention. We then compare these populations to similar groups derived from our population of children with appendicitis. The aim of our study was to determine, retrospectively, whether there are factors unique to early or mild appendicitis in comparison with other cases of pediatric appendicitis.

2. Methods

This was a retrospective chart review at a tertiary care pediatric emergency department (PED) with 27,000 visits annually. We reviewed our records in order to identify four subpopulations of children seen in our facility (two study populations and two comparators). We compared (A) children with pathology-confirmed appendicitis and normal inflammatory markers at diagnosis with (B) children with pathology-confirmed appendicitis and any abnormal inflammatory marker at diagnosis. We then compared (C) children with resolution of sonographic appendicitis with (D) children with medically treated uncomplicated sonographic appendicitis.

Scoring systems for potential appendicitis have not yet been introduced at our facility. Rather, children with suspected appendicitis are examined by a pediatric surgeon in the PED or immediately after entry to the ward. Infrequently, we see children who have sonography that cannot rule out appendicitis, but per surgeon assessment require further evidence of acute appendicitis via laboratory and physical examination prior to commencing therapy. These children are hospitalized by our pediatric surgeons for observation. Given the unfavorable rate of recurrence, our pediatric surgeons generally prefer surgical to medical therapy for acute appendicitis. Thus, children observed as inpatients by our pediatric surgeons for suspected appendicitis do not receive antibiotic coverage in the PED or in the inpatient unit prior to diagnosis on pediatric surgeon re-examination. Only after clinical diagnosis of appendicitis by the pediatric surgeon is therapy initiated, most often surgical therapy. Our surgeons’ preference for surgical therapy provided the unique opportunity to study children presenting with normal inflammatory markers and appendicitis as confirmed by pathological examination of the appendix. The preference for observation without antibiotic coverage allowed the study of children, for whom sonography suggested appendicitis, who had complete resolution of symptoms while hospitalized.

We used keyword searches of our facility’s electronic medical records (EMRs) (Chameleon, Elad Health, Tel Aviv, Israel) to identify all children ages 0-18 treated in the pediatric emergency department (PED) or any inpatient unit and diagnosed with appendicitis or periappendiceal abscess, or underwent appendectomy from June 2016 to June 2024. We then searched our EMRs for children admitted to the pediatric surgery ward during the study period with all diagnosis codes relevant to observation for possible appendicitis. Variables reviewed include date, time and duration of PED visit, presenting symptoms, laboratory and imaging results, PED treatment, and surgical and pathology reports.

Children hospitalized for possible appendicitis who received any antibiotic per mouth or intravenously were classified as having received medical treatment. Those who did not receive antibiotic therapy were classified as having spontaneously resolved appendicitis. We defined complicated appendicitis as perforation or abscess formation on pathology or CT, or perforation or abscess on surgical report.

Normal inflammatory markers were defined as white blood cell count (WBC) below 10 k/µL, neutrophil count below 7.5 k/µL and less than 75% of WBC. These cutoffs are not suggestive of appendicitis on both the Alvarado and Pediatric Appendicitis Score, and were found to be highly sensitive cutoffs in a recent metanalysis of laboratory performance in pediatric appendicitis [

13]. Additionally, our cohort of children with normal inflammatory markers had c-reactive protein (CRP) below 0.8 mg/dL, the minimum upper limit of normal across various age groups [

14].

From the cohort with appendicitis, we excluded hospital visits with incidental or interval appendectomies (data on children with interval appendectomies were captured in the visit at which the diagnosis of appendicitis was made), children with inflammatory bowel disease, children without both complete blood count and CRP, and children who did not have appendicitis confirmed on pathology or CT. If unclear, a board-certified pathologist clarified whether pathology results indicated acute appendicitis. From the cohort admitted to the pediatric surgical service, we excluded children for whom appendicitis was not in the differential diagnosis on admission, children who had prior appendectomy, children for whom no appendix was viewed on radiology-performed ultrasound, and children who had pathogenic stool culture or stool polymerase chain reaction (PCR). We excluded from the medical therapy group (our comparator for spontaneous resolution) children with abscess or evidence of perforation on any imaging during hospitalization, and children who were treated medically without sonographic confirmation of appendicitis. In order to construct a fair comparator to children with spontaneous resolution (to compare medical therapy with spontaneous resolution in a single ward) we excluded from the medical therapy group children over the age of 15 years, who per hospital policy are hospitalized in the adult surgical unit rather than in the pediatric surgical ward.

The country-wide Ofek EMR database, which includes both outpatient visits as well as hospitalizations, was reviewed to verify that the children in our series did not have growth on stool culture within a week of hospitalization, and did not return to a medical facility with appendicitis. To confirm the accuracy of the initial sonographic diagnosis of appendicitis in children with spontaneous resolution, two study radiologists (co-authors KK and LPB) were blinded to clinical data and reviewed the images for diameter, compressibility, hyperemia, free fluid, appendicolith, thickened appendiceal wall, fat stranding, and associated mesenteric lymphadenopathy.

Categorical and nominal variables are reported by prevalence and percentages, and continuous variables are reported as means and standard deviation or as medians and interquartile range (IQR). Continuous variables between the various study groups were tested for normality by the Shapiro–Wilk test, and when abnormal distribution was found, non-parametric tests were performed. The Kruskal–Wallis test was conducted to compare three or more groups and the Wilcoxon rank sum test was performed to compare two groups. Categorical and nominal variables were analyzed by Pearson’s chi-square (χ

2) test or Fisher exact test. Results were considered significant when the

p-value was less than 0.05. Analyses were performed with SPSS27 and R Core Team (2021, R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. URL

https://www.R-project.org/, accessed on 28 November 2024).

3. Results

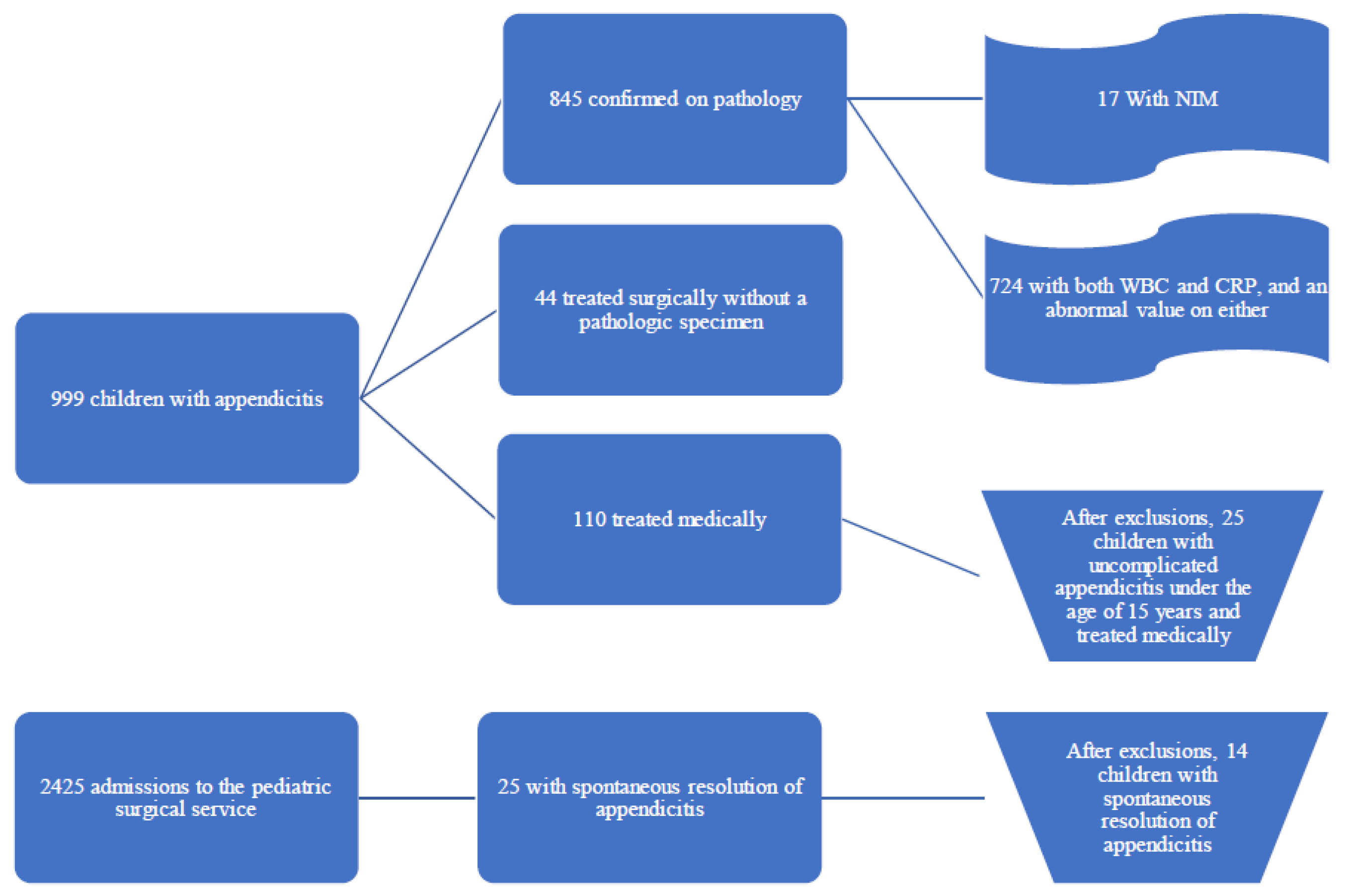

A total of 999 children were diagnosed with appendicitis, of whom 845 had appendicitis on pathologic examination (

Figure 1). With 27,000 visits annually, and a total of 216,000 visits from June 2016 to June 2024, the 999 children that were diagnosed with appendicitis is a representative sample with a ±4% margin of error and confidence interval of 99%.

Of the 845 children with appendicitis on pathologic examination, 724 had both WBC and CRP results that showed elevated WBC, neutrophilia, and/or elevated CRP. Of the 845 children with appendicitis on pathologic examination, 17 had NIMs (

Table S1). All children with NIMs had appendicitis on pathology. Twelve of the seventeen had periappendicitis.

The cohort with NIMs and appendicitis were compared to those with abnormal laboratory markers (

Table 1). The average age for children with abnormal inflammatory markers was 10.8 years, while the average age for children with NIMs was 11.9 years (

p = 0.2). Children with NIMs were predominantly male (59%, compared with 65% for those with elevated inflammatory markers,

p = 0.6), and, in both groups, over 40% were in the 10–15-years age range (

p = 0.6). Only the association with vomiting was found to have statistical significance—children with NIMs were less than half as likely to present with vomiting than children with elevated inflammatory markers (61% versus 24%,

p = 0.002).

During the study period, 2425 children were admitted to the pediatric surgery service. After exclusions, 25 children were candidates for spontaneous resolution of appendicitis. Two children (seen in 2017 and 2019) were deemed by both study radiologists to have images in which the appendix was not well viewed, and were excluded. Nine children were found by both reviewing radiologists to have appendiceal diameters of 6 mm or below without wall thickness and were excluded. Thus, 14 children were included in the study (

Table S2).

In all cases of spontaneous resolution, there was agreement between study radiologists on at least five of the eight sonographic parameters listed in “Methods”

Section 2 (

Table S3). In two children there was agreement between study radiologists that stored images were absent all secondary signs of appendicitis. Both children had multiple hospital admissions for abdominal pain with no alternative diagnosis found.

Of 110 children admitted from the pediatric emergency department for medical treatment of appendicitis, 25 were over the age of 15 years and were hospitalized in the adult surgical unit, 38 had an abscess on imaging, and 17 were diagnosed with appendicitis without having appendicitis on imaging. Five children were felt on study review to have sonographic findings that did not meet the criteria for appendicitis. Thus, the medical therapy group consisted of 25 children below the age of 15 years.

Males comprised 64% of children with spontaneous resolution, compared with 52% of children receiving medical therapy (

p = 0.458) (

Table 2). Children with spontaneous resolution were, on average, three years younger than children who received medical therapy (8.7 years versus 11.7 years,

p = 0.008). Mean length of PED stay was considerably longer for children with spontaneous resolution (370 versus 239 min,

p = 0.007). No child with spontaneous resolution presented with diarrhea (0% versus 28% for those treated medically,

p = 0.029). White blood cell count (14.1 versus 10.2,

p = 0.005) and appendiceal diameter (8.6 mm versus 7.6 mm,

p = 0.078) were higher for children with conservative treatment. Children receiving medical treatment received intravenous analgesia more frequently (88% versus 50%,

p = 0.009). More resources were used for medical treatment—these children had longer hospitalizations (3.5 versus 1.6 days,

p = 0.001) and more frequently received repeat bloodwork (68% versus 36%,

p = 0.051). Five children with spontaneous resolution had more than one hospital admission for abdominal pain.

Two children returned with appendicitis confirmed on pathological examination after completing medical treatment. One patient with spontaneous resolution of appendicitis, a 9-year-old female, had recurrence of appendicitis 18 months after initial presentation and underwent appendectomy. She was initially hospitalized for three days and had neither leukocytosis nor neutrophilia on three successive blood draws. She did have a CRP that fell from 3.7 mg/dL to 1.4 mg/dL. On return, she had both leukocytosis of 23 K cells/micron with neutrophilia, and an unremarkable CRP. On pathology, adipose tissue from the omentum showed acute and chronic inflammation.

4. Discussion

This is the first review of pediatric appendicitis that focuses exclusively on cases that could be deemed “mild”: pediatric sonographic appendicitis that resolved without antibiotic or surgical therapy, and pathology-confirmed appendicitis that presented with normal inflammatory markers. In this study, we have gathered the largest series of pediatric appendicitis that spontaneously resolved, as well as the largest series of children with appendicitis presenting with normal inflammatory markers. We aim to demonstrate that there are subgroups of children with appendicitis who have mild presentations of disease, and to determine whether there are characteristics that will allow for their identification. If so, we suggest that a brief observation, with anti-inflammatory therapy (i.e., ketorolac) but without antibiotic therapy, may be warranted, as a very small number may resolve.

Appendicitis presenting with normal inflammatory markers is a rare entity. Staab et. al. reports that 15% of their patients with appendicitis had a WBC count less than 10 k/µL and 22.7% had a neutrophil count less than 75% of WBC [

15]. Kim et. al. studied 949 patients who underwent appendectomy for appendicitis, of whom 205 were pediatric [

16]. Of all cases, 128 (13.5%) had WBC < 11 k/µL and CRP < 0.5 mg/dL, and 39.8% of those with normal inflammatory markers had appendicitis. De Jong et al. studied 1303 adult patients with pathology-confirmed appendicitis and found that 1.8% presented with normal white blood cell count and CRP levels [

17]. In their series, four patients (0.3%) had complicated appendicitis. When looking only at pediatric patients, 10 of 485 children (2%) presented with normal white blood cell count and CRP levels, with no significant differences between children with and without abnormal laboratories. Our NIM rate of 1.9% correlates well with their NIM rate of 2%.

Stefanutti et al. studied pediatric appendicitis and found that WBC count or CRP values alone do not appear to have utility in isolation—the combination of normal WBC and normal CRP was found in only 2 of 100 children with uncomplicated appendicitis and 4 of the 8 cases of negative or normal appendectomy [

18]. To our knowledge, ours is the largest series that studied children with appendicitis and a combination of normal WBC, normal neutrophil count, and normal CRP.

Here, we show that emesis is more commonly found in children with elevated inflammatory markers. Among appendicitis scoring tools, emesis is inconsistently used. For example, the Pediatric Appendicitis Score [

4] and Appendicitis Inflammatory Response score use emesis as a marker of appendicitis [

6], while the pediatric Appendicitis Risk Calculator [

5] does not. The creators of the pediatric Appendicitis Risk Calculator showed that, in a study of inter-rater agreement of historical and physical examination findings in children with and without acute appendicitis, only emesis was found to have high inter-rater agreement [

19]. In the groundwork for a more recently derived decision rule for appendicitis, emesis was one of only two independent predictors of pediatric appendicitis, with a relative risk of three in both univariate and multivariate models [

20]. Thus, it stands to reason that absence of emesis in confirmed appendicitis may be a marker of low risk of progression to complication.

Spontaneous resolution of appendicitis is a similarly rare entity. We identified 14 cases during a period in which 845 cases of appendicitis were confirmed on histology for an incidence of 1.7 cases per 100 cases of histologically confirmed appendicitis. Our series characterizes spontaneous resolution of appendicitis by comparing children with spontaneous resolution with a second group for whom the presentation was likely more suggestive of appendicitis and who received medical therapy. We found that appendicitis that resolves spontaneously, when compared with appendicitis treated medically, has markers of low severity—fewer with spontaneous resolution present with diarrhea, fewer require intravenous analgesia, and inflammatory markers are lower in cases of spontaneous resolution. Extra-intestinal or parenteral diarrhea has been found in other pediatric disease processes, theorized to result from circulating cytokines [

21]. While diarrhea is not used in any of the aforementioned scoring systems, it can be useful as a marker for complicated appendicitis [

22].

Interestingly, children with spontaneous resolution were three years younger on average than children treated medically. They had a length of emergency department stay significantly longer than children treated medically, indicating diagnostic uncertainty (appendiceal diameter in cases of spontaneous resolution was lower, without statistical significance), but were discharged after an average of a day and a half of hospitalization compared with three and a half days for children treated medically. We wonder whether low-risk criteria can be developed to allow for a 12 to-24 h observation period under anti-inflammatory treatment before proceeding to antibiotic therapy.

Spontaneous resolution of appendicitis has been described in adults [

23,

24,

25]. Cobben et al. reported on 60 cases of spontaneous resolution of appendicitis in an adult population. Their recurrence rate was 38%, with an increased rate of recurrence in cases in which appendiceal diameter is above 8 mm [

26]. Lastunen et al. studied 184 adult patients with an Adult Appendicitis Score of 11–15 and less than 24 h of symptoms. Patients were randomized to either early imaging (ultrasound and/or CT) or observation, with those under observation reassessed after 6–8 h. They found that those imaged early were diagnosed more frequently with appendicitis (72% versus 57% in the observation group) [

27]. The difference between the two groups may be due to cases of spontaneous resolution of early appendicitis.

Similarly, a meta-analysis of over 100,000 adult patients found fewer cases of complicated appendicitis when compared with uncomplicated appendicitis during the COVID-19 pandemic year, while a second, multicenter study during the pandemic year came to the same conclusion [

28,

29]. The authors suggest that this decrease represents uncomplicated appendicitis that underwent spontaneous resolution during a period of limited access to health care. A 2007 review concluded that “spontaneous resolution of untreated, non-perforated appendicitis is common” [

30]. Bachur et al. found that ultrasound examination in boys younger than 5 years actually increased negative appendectomy rates across multiple facilities [

31]. Bachur’s study relied on coding data and there is a possibility that appendicitis was diagnosed more frequently due to overreliance on secondary sonograophic signs of appendicitis, or that the appendicitis resolved prior to surgery.

Park et al. randomized 245 adult patients with uncomplicated appendicitis (appendiceal diameter to 11 mm and without signs of perforation) to antibiotic or supportive therapy. Treatment failure was 23.4 percent for supportive therapy and 20.7 percent for antibiotic therapy [

9]. Wang et al. randomized 182 pediatric patients with low-grade sonographic appendicitis (defined there as “an appendix with a smooth submucosal layer or irregular submucosal layer with increased blood flow and no appendiceal mass, abscess, or perforation”) to observation or antibiotic therapy. Their series showed a long-term event-free rate of 60% for patients for whom medical and surgical treatment was withheld, with an average of two years post-diagnosis prior to recurrence [

32].

Several larger studies suggest spontaneous resolution of appendicitis. In children, 21% of radiology-performed ultrasounds conducted to evaluate for appendicitis contain language in the interpretation that creates diagnostic uncertainty [

33]. Early appendicitis due to partial or intermittent obstruction (fecalith or lymphadenopathy that resolve) may be healed by a healthy immune system, as in other bacterial infections. Xu et al. suggests that in cases of increased appendiceal diameter to 8 mm, a thickened lamina propria without secondary signs of appendicitis represents lymphoid hyperplasia rather than acute appendicitis [

34]. Appendiceal wall thickening without secondary signs of appendicitis can be seen in enteritis. We only had three children with spontaneous resolution (one with appendicolith), for whom reviewing radiologists were in agreement on the absence of secondary signs of appendicitis.

Chronic appendicitis can be characterized by intermittent, colicky right-lower quadrant pain and appendiceal fibrosis on pathological examination [

35]. Chronic appendicitis is theorized to result from partial or intermittent appendiceal obstruction, and the incidence in children is unknown. We suggest that spontaneously resolved appendicitis may be a mild form of appendicitis that carries with it a risk of developing into chronic appendicitis. The APPAC III trial group have proposed a research protocol that randomizes adult patients with uncomplicated appendicitis to antibiotic and placebo arms, and may provide an answer to this question [

10].

Here, we use a database of eight years of pediatric appendicitis to look at two unique populations who may be considered low-risk for progression of disease. Our data should be of use in creating a low-risk rule, consisting of history and laboratory evaluation that may allow for a brief observation period prior to commencing definitive therapy and with low risk for further progression to complicated appendicitis. Antibiotic exposure is not risk-free and therefore antibiotic stewardship has become a critical task for those caring for children [

36]. The recent literature has demonstrated success in abbreviated antibiotic treatment for other pediatric bacterial illnesses, such as community-acquired pneumonia and urinary tract infection [

37,

38]. Further research into the effect of anti-inflammatory therapy and brief observation without antibiotics of a select population of children with early appendicitis may be warranted.

Limitations

Our study is retrospective and, in cases of spontaneous resolution, did not provide a CT or pathologic confirmation of appendicitis. Ultrasound images were reviewed retrospectively by the study radiologists. Ultrasound is a dynamic examination and the inability of the study radiologists to examine or re-examine the patients is a limitation.

As these cases review sonographic appendicitis diagnosed without further imaging or surgical confirmation, we cannot exclude that the appendiceal inflammation was caused by gastrointestinal illness that subsequently resolved. Our PED does not use a scoring system to grade the pretest probability of appendicitis. Our PED receives children to the age of 18 while our pediatric surgery department hospitalizes children to the age of 15. Children from age 15 to 18 years are hospitalized in the general surgery department and would not have been captured in a review of pediatric surgical inpatient admissions.

As we did not evaluate NIM prospectively, we do not know how many children had NIM without sonographic evaluation, were discharged from the PED, or experienced spontaneous resolution of an aborted appendicitis.