Burnout in Medical Specialists Redeployed to Emergency Care during the COVID-19 Pandemic

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Specialists Investigated

2.2. Study Type and Design

3. Results

3.1. Google Scholar Search

3.1.1. Cardiology

3.1.2. Dermatology

3.1.3. Endocrinology

3.1.4. Family Medicine

3.1.5. Gastroenterology

3.1.6. Internal Medicine

3.1.7. Nephrology

3.1.8. Neurology

3.1.9. Obstetrics

3.1.10. Orthopedics

3.1.11. Pediatrics

3.1.12. Plastic Surgery

3.1.13. Psychiatry

3.1.14. Radiology

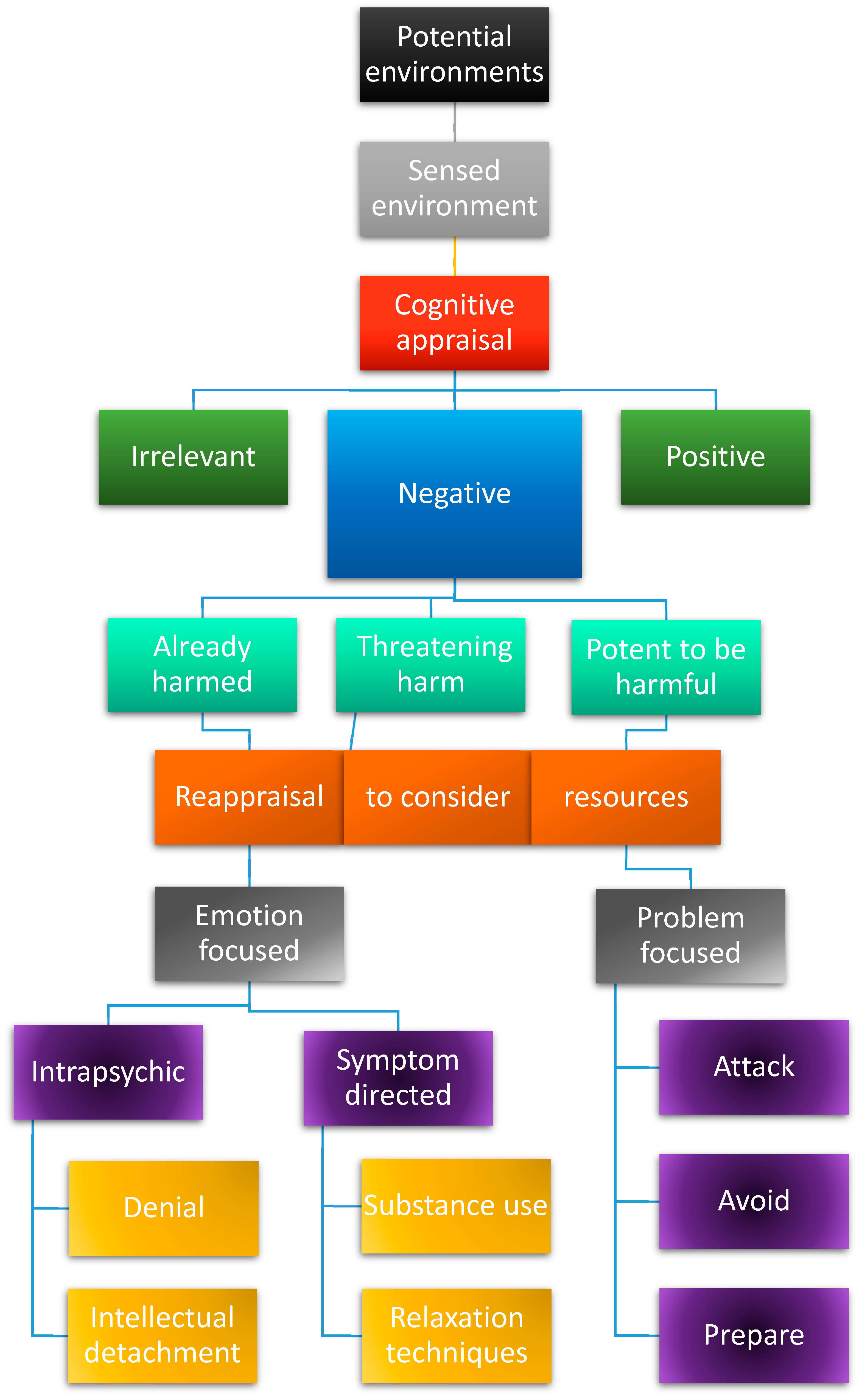

3.2. Coping Strategies

4. Discussion

4.1. Ranking of Medical Specialties Regarding Positive Coping

4.2. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Freudenberger, H.J. Staff Burn-Out. J. Soc. Issues 1974, 30, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Burn-Out an “Occupational Phenomenon”: International Classification of Diseases; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Tabur, A.; Elkefi, S.; Emhan, A.; Mengenci, C.; Bez, Y.; Asan, O. Anxiety, Burnout and Depression, Psychological Well-Being as Predictor of Healthcare Professionals’ Turnover during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Study in a Pandemic Hospital. Healthcare 2022, 10, 525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharifi, M.; Asadi-Pooya, A.A.; Mousavi-Roknabadi, R.S. Burnout among Healthcare Providers of COVID-19; a Systematic Review of Epidemiology and Recommendations: Burnout in Healthcare Providers. Arch. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2020, 9, e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rigby, J.; Satija, B. WHO Declares End to COVID Global Health Emergency; Reuters: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Morgantini, L.A.; Naha, U.; Wang, H.; Francavilla, S.; Acar, Ö.; Flores, J.M.; Crivellaro, S.; Moreira, D.; Abern, M.; Eklund, M.; et al. Factors Contributing to Healthcare Professional Burnout during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Rapid Turnaround Global Survey. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0238217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cucinotta, D.; Vanelli, M. WHO Declares COVID-19 a Pandemic. Acta Bio Medica Atenei Parm. 2020, 91, 157–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schablon, A.; Kersten, J.F.; Nienhaus, A.; Kottkamp, H.W.; Schnieder, W.; Ullrich, G.; Schäfer, K.; Ritzenhöfer, L.; Peters, C.; Wirth, T. Risk of Burnout among Emergency Department Staff as a Result of Violence and Aggression from Patients and Their Relatives. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alanazy, A.R.M.; Alruwaili, A. The Global Prevalence and Associated Factors of Burnout among Emergency Department Healthcare Workers and the Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chor, W.P.D.; Ng, W.M.; Cheng, L.; Situ, W.; Chong, J.W.; Ng, L.Y.A.; Mok, P.L.; Yau, Y.W.; Lin, Z. Burnout amongst Emergency Healthcare Workers during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Multi-Center Study. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2021, 46, 700–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, R.M.; Montoy, J.C.C.; Hoth, K.F.; Talan, D.A.; Harland, K.K.; Eyck, P.T.; Mower, W.; Krishnadasan, A.; Santibanez, S.; Mohr, N.; et al. Symptoms of Anxiety, Burnout, and PTSD and the Mitigation Effect of Serologic Testing in Emergency Department Personnel During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2021, 78, 35–43.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Mu, M.; He, Y.; Cai, Z.; Li, Z. Burnout in Emergency Medicine Physicians: A Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review. Medicine 2020, 99, e21462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verougstraete, D.; Hachimi Idrissi, S. The Impact of Burn-out on Emergency Physicians and Emergency Medicine Residents: A Systematic Review. Acta Clin. Belg. 2020, 75, 57–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schoenfeld, E.M.; Goff, S.L.; Elia, T.R.; Khordipour, E.R.; Poronsky, K.E.; Nault, K.A.; Lindenauer, P.K.; Mazor, K.M. Physician-Identified Barriers to and Facilitators of Shared Decision-Making in the Emergency Department: An Exploratory Analysis. Emerg. Med. J 2019, 36, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cunningham, A.T.; Felter, J.; Smith, K.R.; Sifri, R.; Arenson, C.; Patel, A.; Kelly, E.L. Burnout and Commitment After 18 Months of the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Follow-Up Qualitative Study with Primary Care Teams. J. Am. Board Fam. Med. 2023, 36, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sert-Ozen, A.; Kalaycioglu, O. The Effect of Occupational Moral Injury on Career Abandonment Intention Among Physicians in the Context of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Saf. Health Work 2023, 14, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Vries, N.; Maniscalco, L.; Matranga, D.; Bouman, J.; De Winter, J.P. Determinants of Intention to Leave among Nurses and Physicians in a Hospital Setting during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0300377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macaron, M.M.; Segun-Omosehin, O.A.; Matar, R.H.; Beran, A.; Nakanishi, H.; Than, C.A.; Abulseoud, O.A. A Systematic Review and Meta Analysis on Burnout in Physicians during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Hidden Healthcare Crisis. Front. Psychiatry 2023, 13, 1071397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dionisi, T.; Sestito, L.; Tarli, C.; Antonelli, M.; Tosoni, A.; D’Addio, S.; Mirijello, A.; Vassallo, G.A.; Leggio, L.; Gasbarrini, A.; et al. Risk of Burnout and Stress in Physicians Working in a COVID Team: A Longitudinal Survey. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2021, 75, e14755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, K.H.J.; Murali, K.; Kamposioras, K.; Punie, K.; Oing, C.; O’Connor, M.; Thorne, E.; Amaral, T.; Garrido, P.; Lambertini, M.; et al. The Concerns of Oncology Professionals during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Results from the ESMO Resilience Task Force Survey II. ESMO Open 2021, 6, 100199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veronese, C.; Williams, M.; Dickson, J.; Bush, M.; Shenvi, C. Determining the Educational Value of an Emergency Medicine Rotation for Non-Emergency Medicine Residents. Cureus 2023, 15, e47284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gusenbauer, M.; Haddaway, N.R. Which Academic Search Systems Are Suitable for Systematic Reviews or Meta-analyses? Evaluating Retrieval Qualities of Google Scholar, PubMed, and 26 Other Resources. Res. Synth. Methods 2020, 11, 181–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aspers, P.; Corte, U. What Is Qualitative in Qualitative Research. Qual. Sociol. 2019, 42, 139–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taherdoost, H. What Are Different Research Approaches? Comprehensive Review of Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Method Research, Their Applications, Types, and Limitations. J. Manag. Sci. Eng. Res. 2022, 5, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, R.S. Coping Theory and Research: Past, Present, and Future. Psychosom. Med. 1993, 55, 234–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaillant, G.E. Adaptation to Life, 1st ed.; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1995; ISBN 978-0-674-00414-6. [Google Scholar]

- Haan, N. A tripartite model of ego functioning values and clinical and research applications. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 1969, 148, 14–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menninger, K. Regulatory Devices of the Ego under Major Stress. Int. J. Psycho-Anal. 1954, 35, 412–420. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus, R.S.; Folkman, S. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1984; ISBN 978-0-8261-4191-0. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus, R.S. Fifty Years of the Research and Theory of R.S. Lazarus: An Analysis of Historical and Perennial Issues; LEA Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA; London, UK, 1998; ISBN 978-0-8058-2657-9. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus, R.S. The Psychology of Stress and Coping. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 1985, 7, 399–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Josephson, R.A.; Gillombardo, C.B. Cardiovascular Services in Covid-19-Impact of the Pandemic and Lessons Learned. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2023, 76, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kulkarni, P.; Mahadevappa, M.; Alluri, S. COVID-19 Pandemic and the Impact on the Cardiovascular Disease Patient Care. Curr. Cardiol. Rev. 2020, 16, 173–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, R.F.; Alasnag, M.; Batchelor, W.B.; Sharma, A.; Luse, E.; Drewes, M.; Welt, F.G.; Itchhaporia, D.; Henry, T.D. The Ongoing National Medical Staffing Crisis: Impacts on Care Delivery for Interventional Cardiologists. J. Soc. Cardiovasc. Angiogr. Interv. 2022, 1, 100307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadler, D.; DeCara, J.M.; Herrmann, J.; Arnold, A.; Ghosh, A.K.; Abdel-Qadir, H.; Yang, E.H.; Szmit, S.; Akhter, N.; Leja, M.; et al. Perspectives on the COVID-19 Pandemic Impact on Cardio-Oncology: Results from the COVID-19 International Collaborative Network Survey. Cardio-Oncol. 2020, 6, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhargava, S.; Sarkar, R.; Kroumpouzos, G. Mental Distress in Dermatologists during COVID-19 Pandemic: Assessment and Risk Factors in a Global, Cross-sectional Study. Dermatol. Ther. 2020, 33, e14161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samimi, S.; Choi, J.; Rosman, I.S.; Rosenbach, M. Impact of COVID-19 on Dermatology Residency. Dermatol. Clin. 2021, 39, 609–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, P.; Dorrell, D.N.; Feldman, S.R.; Huang, W.W. The Impact of the Coronavirus Disease 2019 Pandemic on Dermatologist Burnout: A Survey Study. Dermatol. Online J. 2021, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helm, M.F.; Kimball, A.B.; Butt, M.; Stuckey, H.; Costigan, H.; Shinkai, K.; Nagler, A.R. Challenges for Dermatologists during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Qualitative Study. Int. J. Women’s Dermatol. 2022, 8, e013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elbarbary, N.S.; Dos Santos, T.J.; De Beaufort, C.; Wiltshire, E.; Pulungan, A.; Scaramuzza, A.E. The Challenges of Managing Pediatric Diabetes and Other Endocrine Disorders During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Results From an International Cross-Sectional Electronic Survey. Front. Endocrinol. 2021, 12, 735554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loscalzo, Y.; Marucci, S.; Garofalo, P.; Attanasio, R.; Lisco, G.; De Geronimo, V.; Guastamacchia, E.; Giannini, M.; Triggiani, V. Assessment of Burnout Levels Before and During COVID-19 Pandemic: AWeb-Based Survey by the (Italian) Association of Medical Endocrinologists (AME). Endocr. Metab. Immune Disord.-Drug Targets 2021, 21, 2238–2252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agha, A.; Basu, A.; Anwar, E.; Hanif, W. Burnout among Diabetes Specialist Registrars across the United Kingdom in the Post-Pandemic Era. Front. Med. 2024, 11, 1367103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manzella, A.; Kravchenko, T.; Kheng, M.; Chao, J.; Laird, A.M.; Pitt, H.A.; Beninato, T. Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Endocrine Operations in the United States. Am. J. Surg. 2024, 228, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Monte, C.; Monaco, S.; Mariani, R.; Di Trani, M. From Resilience to Burnout: Psychological Features of Italian General Practitioners During COVID-19 Emergency. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 567201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurzthaler, I.; Kemmler, G.; Holzner, B.; Hofer, A. Physician’s Burnout and the COVID-19 Pandemic—A Nationwide Cross-Sectional Study in Austria. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 784131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ofei-Dodoo, S.; Loo-Gross, C.; Kellerman, R. Burnout, Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Among Family Physicians in Kansas Responding to the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Am. Board Fam. Med. 2021, 34, 522–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiliç, O.H.T.; Anil, M.; Varol, U.; Sofuoğlu, Z.; Çoban, İ.; Gülmez, H.; Güvendi, G.; Mete, B.D. Factors Affecting Burnout in Physicians during COVID-19 Pandemic. Ege Tıp Derg. 2021, 60, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekmektzoglou, K.; Tziatzios, G.; Siau, K.; Pawlak, K.M.; Rokkas, T.; Triantafyllou, K.; Arvanitakis, M.; Gkolfakis, P. Covid-19: Exploring the “New Normal” in Gastroenterology Training. Acta Gastro-Enterol. Belg. 2021, 84, 623–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, J.-J. Psychosocio-Economic Impacts of COVID-19 on Gastroenterology and Endoscopy Practice. Gastroenterol. Rep. 2021, 9, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marlicz, W.; Koulaouzidis, A.; Charisopoulou, D.; Jankowski, J.; Marlicz, M.; Skonieczna-Zydecka, K.; Krynicka, P.; Loniewski, I.; Samochowiec, J.; Rydzewska, G.; et al. Burnout in Healthcare–the Emperor’s New Clothes. Gastroenterol. Rev./Przegląd Gastroenterol. 2023, 18, 274–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacy, B.E.; Cangemi, D.J.; Burke, C.A. Burnout in Gastrointestinal Providers. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhadi, M.; Msherghi, A.; Elgzairi, M.; Alhashimi, A.; Bouhuwaish, A.; Biala, M.; Abuelmeda, S.; Khel, S.; Khaled, A.; Alsoufi, A.; et al. Burnout Syndrome Among Hospital Healthcare Workers During the COVID-19 Pandemic and Civil War: A Cross-Sectional Study. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 579563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buran, F.; Altın, Z. Burnout among Physicians Working in a Pandemic Hospital during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Leg. Med. 2021, 51, 101881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macía-Rodríguez, C.; Alejandre De Oña, Á.; Martín-Iglesias, D.; Barrera-López, L.; Pérez-Sanz, M.T.; Moreno-Diaz, J.; González-Munera, A. Burn-out Syndrome in Spanish Internists during the COVID-19 Outbreak and Associated Factors: A Cross-Sectional Survey. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e042966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Madrid, M.N.; Pastor-Moreno, G.; Albert-Lopez, E.; Pastor-Valero, M. “You Knew You Had to Be There, It Had to Be Done”: Experiences of Health Professionals Who Faced the COVID-19 Pandemic in One Public Hospital in Spain. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1089565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pivert, K.A.; Boyle, S.M.; Halbach, S.M.; Chan, L.; Shah, H.H.; Waitzman, J.S.; Mehdi, A.; Norouzi, S.; Sozio, S.M. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Nephrology Fellow Training and Well-Being in the United States: A National Survey. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2021, 32, 1236–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nair, D.; Brereton, L.; Hoge, C.; Plantinga, L.C.; Agrawal, V.; Soman, S.S.; Choi, M.J.; Jaar, B.G.; Soman, S.; Jaar, B.; et al. Burnout Among Nephrologists in the United States: A Survey Study. Kidney Med. 2022, 4, 100407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pawłowicz-Szlarska, E.; Forycka, J.; Harendarz, K.; Stanisławska, M.; Makówka, A.; Nowicki, M. Organizational Support, Training and Equipment Are Key Determinants of Burnout among Dialysis Healthcare Professionals during the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Nephrol. 2022, 35, 2077–2086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvaskandan, H.; Nimmo, A.; Savino, M.; Afuwape, S.; Brand, S.; Graham-Brown, M.; Medcalf, J.; Cockwell, P.; Beckwith, H. Burnout and Long COVID among the UK Nephrology Workforce: Results from a National Survey Investigating the Impact of COVID-19 on Working Lives. Clin. Kidney J. 2022, 15, 517–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majersik, J.J.; Reddy, V.K. Acute Neurology during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Supporting the Front Line. Neurology 2020, 94, 1055–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayele, R.; Macchi, Z.A.; Dini, M.; Bock, M.; Katz, M.; Pantilat, S.Z.; Jones, J.; Kluger, B.M. Experience of Community Neurologists Providing Care for Patients With Neurodegenerative Illness During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Neurology 2021, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goyal, T.; Probasco, J.C.; Gold, C.A.; Klein, J.P.; Weathered, N.R.; Thakur, K.T. Neurohospitalist Practice and Well-Being During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Neurohospitalist 2021, 11, 333–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kristoffersen, E.S.; Winsvold, B.S.; Sandset, E.C.; Storstein, A.M.; Faiz, K.W. Experiences, Distress and Burden among Neurologists in Norway during the COVID-19 Pandemic. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0246567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Piccolo, L.; Donisi, V.; Raffaelli, R.; Garzon, S.; Perlini, C.; Rimondini, M.; Uccella, S.; Cromi, A.; Ghezzi, F.; Ginami, M.; et al. The Psychological Impact of COVID-19 on Healthcare Providers in Obstetrics: A Cross-Sectional Survey Study. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 632999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riggan, K.A.; Reckhow, J.; Allyse, M.A.; Long, M.; Torbenson, V.; Rivera-Chiauzzi, E.Y. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Obstetricians/Gynecologists. Mayo Clin. Proc. Innov. Qual. Outcomes 2021, 5, 1128–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, N.; Mattern, E.; Cignacco, E.; Seliger, G.; König-Bachmann, M.; Striebich, S.; Ayerle, G.M. Effects of the Covid-19 Pandemic on Maternity Staff in 2020—A Scoping Review. BMC Health Serv. Res 2021, 21, 1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogaert, K.C.; Lieb, W.E.; Glazer, K.B.; Wang, E.; Stone, J.L.; Howell, E.A. Stress and the Psychological Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Frontline Obstetrics and Gynecology Providers. Am. J. Perinatol. 2022, 29, 1596–1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Humadi, S.M.; Cáceda, R.; Bronson, B.; Paulus, M.; Hong, H.; Muhlrad, S. Orthopaedic Surgeon Mental Health During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Geriatr. Orthop. Surg. Rehabil. 2021, 12, 215145932110352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazarides, A.L.; Belay, E.S.; Anastasio, A.T.; Cook, C.E.; Anakwenze, O.A. Physician Burnout and Professional Satisfaction in Orthopedic Surgeons during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Work 2021, 69, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mavrogenis, A.F.; Scarlat, M.M. Stress, Anxiety, and Burnout of Orthopaedic Surgeons in COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. Orthop. (SICOT) 2022, 46, 931–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ambrosio, L.; Vadalà, G.; Russo, F.; Papalia, R.; Denaro, V. The Role of the Orthopaedic Surgeon in the COVID-19 Era: Cautions and Perspectives. J. Exp. Orthop. 2020, 7, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laventhal, N.T.; Basak, R.B.; Dell, M.L.; Elster, N.; Geis, G.; Macauley, R.C.; Mercurio, M.R.; Opel, D.J.; Shalowitz, D.I.; Statter, M.B.; et al. Professional Obligations of Clinicians and Institutions in Pediatric Care Settings during a Public Health Crisis: A Review. J. Pediatr. 2020, 224, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Treluyer, L.; Tourneux, P. Burnout among Paediatric Residents during the COVID-19 Outbreak in France. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2021, 180, 627–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nigri, L.; Carrasco-Sanz, A.; Pop, T.L.; Giardino, I.; Vural, M.; Ferrara, P.; Indrio, F.; Pettoello-Mantovani, M. Burnout in Primary Care Pediatrics and the Additional Burden from the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Pediatr. 2023, 260, 113447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivas-García, A.; Míguez-Navarro, M.C.; Ferrero-García-Loygorri, C.; Marañón, R.; Vázquez-López, P. Burnout Syndrome in Paediatricians Working in Paediatric Emergency Care Settings. Prevalence and Associated Factors: A Multilevel Analysis. An. Pediatría (Engl. Ed.) 2023, 98, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKenzie, E.L.; Poore, S.O. Slowing the Spread and Minimizing the Impact of COVID-19: Lessons from the Past and Recommendations for the Plastic Surgeon. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2020, 146, 681–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crowe, C.S.; Lopez, J.; Morrison, S.D.; Drolet, B.C.; Janis, J.E.; On behalf of the Resident Council Wellness and Education Study Group. The Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Resident Education and Wellness: A National Survey of Plastic Surgery Residents. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2021, 148, 462e–474e. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, J.; Zhao, R.; Yi, J.; Otterburn, D.; Patel, A.; Szpalski, C.; Tanna, N.; Taub, P.J.; Weichman, K.E.; Ricci, J.A. Frontline Reporting from the Epicenter of a Global Pandemic: A Survey of the Impact of COVID-19 on Plastic Surgery Training in New York and New Jersey. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2022, 149, 130e–138e. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gologram, M.; Lomiguen, C.; Chin, J.; Terrell, M. Mental Health and Quality of Life Considerations: Plastic and Cosmetic Surgery During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Am. J. Cosmet. Surg. 2023, 40, 162–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bojdani, E.; Rajagopalan, A.; Chen, A.; Gearin, P.; Olcott, W.; Shankar, V.; Cloutier, A.; Solomon, H.; Naqvi, N.Z.; Batty, N.; et al. COVID-19 Pandemic: Impact on Psychiatric Care in the United States. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 289, 113069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhamees, A.A.; Assiri, H.; Alharbi, H.Y.; Nasser, A.; Alkhamees, M.A. Burnout and Depression among Psychiatry Residents during COVID-19 Pandemic. Hum. Resour. Health 2021, 19, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öğütlü, H.; McNicholas, F.; Türkçapar, H. Stress and Burnout in Psychiatrists in Turkey During COVID-19 Pandemic. Psychiatr. Danub. 2021, 33, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yellowlees, P. Impact of COVID-19 on Mental Health Care Practitioners. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 2022, 45, 109–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirjian, N.L.; Fields, B.K.K.; Song, C.; Reddy, S.; Desai, B.; Cen, S.Y.; Salehi, S.; Gholamrezanezhad, A. Impacts of the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Pandemic on Healthcare Workers: A Nationwide Survey of United States Radiologists. Clin. Imaging 2020, 68, 218–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coppola, F.; Faggioni, L.; Neri, E.; Grassi, R.; Miele, V. Impact of the COVID-19 Outbreak on the Profession and Psychological Wellbeing of Radiologists: A Nationwide Online Survey. Insights Imaging 2021, 12, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.L.; Chen, R.C.; Teo, I.; Chaudhry, I.; Heng, A.L.; Zhuang, K.D.; Tan, H.K.; Tan, B.S. A Survey of Anxiety and Burnout in the Radiology Workforce of a Tertiary Hospital during the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Med. Imaging Radiat. Oncol. 2021, 65, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oprisan, A.; Baettig-Arriagada, E.; Baeza-Delgado, C.; Martí-Bonmatí, L. Prevalence of Burnout Syndrome during the COVID-19 Pandemic and Associated Factors. Radiol. (Engl. Ed.) 2022, 64, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Folkman, S.; Moskowitz, J.T. Positive Affect and the Other Side of Coping. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 647–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folkman, S. Personal Control and Stress and Coping Processes: A Theoretical Analysis. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1984, 46, 839–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunsinger, N.; Hammarlund, R.; Crapanzano, K. Mental Health Appointments in the Era of COVID-19: Experiences of Patients and Providers. Ochsner J. 2021, 21, 335–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uscher-Pines, L.; Parks, A.M.; Sousa, J.; Raja, P.; Mehrotra, A.; Huskamp, H.A.; Busch, A.B. Appropriateness of Telemedicine Versus In-Person Care: A Qualitative Exploration of Psychiatrists’ Decision Making. Psychiatr. Serv. 2022, 73, 849–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Medical Specialty | Emergency Experienced | Burnout Response | Patient Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiology | Volume and duration of acute hospitalization decreased, resulting in preventable deaths | Unanticipated dissatisfaction and disengagement, leading to mass resignations | Fewer cardiologists, longer wait times, and fewer tests; telemedicine adopted |

| Dermatology | Training in dermatology suspended; residents worked on non-dermatological cases | Women worried especially about their future, their family, and reduced compensation | Telemedicine adopted; found less effective, because dermatology “very visual” |

| Endocrinology | For type 1 diabetics, unable to sustain consistent care; endocrine operations reduced | Dissatisfaction from reduced patient care; notable decline in operations performed | Thyroid and parathyroid operations remain decreased; telemedicine adopted |

| Family medicine | Became part of the frontline for COVID-19 treatment, difficulties managing workload | Women and those in the early stages of their careers are most affected | Increase in use of telephone calls, and mistakes made during treatment. |

| Gastroenterology | Field particularly susceptible to the virus; worked in isolation from colleagues and family | High turnover; women and younger physicians are most affected | Hours curtailed, telemedicine introduced, and increased litigious environment |

| Internal medicine | Overwork, lack of compensation, verbal abuse, and fear of malpractice | No mass resignations, teams worked together supported by the institutions | Patient care maintained at expected level; increased litigiousness environment |

| Nephrology | Most patients have COVID-19, telehealth adopted; strict infection control enforced | Little, but related to poor institutional support regarding equipment and remuneration | Retraining of patients and their families; greater precautions taken during dialysis |

| Neurology | A significant number were reassigned to treat COVID-19 in general medicine | Experienced by those who were reassigned as a feeling of disempowerment | Admission, transfer, and options for rehabilitation reduced |

| Obstetrics | Infection avoidance from COVID-19 highlighted over delivery safety | Younger members most affected; retired members called back for deliveries | Masked during delivery, poor communication with doctor, partner not allowed present |

| Orthopedics | Residents were reassigned to frontline activities; urgency in elective surgeries altered | Burnout related to few, mostly younger surgeons; resilience found prevalent | Telemedicine was adopted for outpatient visits; significant wait lists for surgeries |

| Pediatrics | Fewer emergencies than other specialties; children less affected by the COVID-19 virus | Emergency work found the cause of chronic exhaustion and sleep disorders | Emergency patients are more complex, requiring high level of skill to treat |

| Plastic surgery | Residents redeployed to emergencies; only cancer-related surgeries continued | Training hours had to be made up in six months; increase in the number of errors | Elective surgeries postposed in hospitals; backlog increases private facilities’ surgeries |

| Psychiatry | Psychiatrists overburdened as a result of the accompanying “mental health pandemic” | Residents, child and adult psychiatrists affected; telepsychiatry improves their health | Separate wards for COVID-19 positive and negative; many patients prefer telemedicine |

| Radiology | With fewer procedures, reduced need for X-rays; radiologists were handing out PPE * | When strategies were developed, less burnout; without them, burnout increased | X-rays limited to emergencies; radiologists redeployed to the emergency department |

| Medical Specialty | Coping Strategy | Rank |

|---|---|---|

| Cardiology | Mass resignation; telemedicine adopted | 14 |

| Dermatology | Virtual learning and telemedicine adopted | 12 |

| Endocrinology | Decreased patient care; telemedicine adopted | 10 |

| Family medicine | Telemedicine adopted; reduced attentiveness | 11 |

| Gastroenterology | Physician turnover, reduced hours, and malpractice worries | 13 |

| Internal medicine | Effective institutional restructuring and teamwork | 3 |

| Nephrology | Preparedness, strict infection control, and institutional aid | 1 |

| Neurology | Telemedicine; reduced self-care and rehabilitation options | 8 |

| Obstetrics | Telemedicine; retired staff assist in vaginal deliveries | 5 |

| Orthopedics | Reconsideration of urgency definition; telemedicine | 7 |

| Pediatrics | SARS-devised strategies; feeling insufficiently skilled | 6 |

| Plastic surgery | Reduced elective surgeries; increase in private clinics | 9 |

| Psychiatry | Revolutionary proactive use of telemedicine | 2 |

| Radiology | Use of portable equipment, teamwork, and frequent rotations | 4 |

| Medical Specialty | Ensures Viability | Burnout Resisted | Excellent Care |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nephrology | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Psychiatry | Yes | Somewhat | Yes |

| Internal medicine | Yes | Somewhat | Yes |

| Radiology | Yes | Somewhat | Yes |

| Obstetrics | Yes | Yes | Somewhat |

| Pediatrics | Yes | Somewhat | Somewhat |

| Orthopedics | Yes | Yes | Somewhat |

| Neurology | Somewhat | Yes | No |

| Plastic surgery | Somewhat | Yes | No |

| Endocrinology | Yes | Somewhat | No |

| Family medicine | Yes | Somewhat | No |

| Dermatology | Somewhat | Somewhat | No |

| Gastroenterology | No | Somewhat | No |

| Cardiology | No | Yes | No |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nash, C. Burnout in Medical Specialists Redeployed to Emergency Care during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Emerg. Care Med. 2024, 1, 176-192. https://doi.org/10.3390/ecm1020019

Nash C. Burnout in Medical Specialists Redeployed to Emergency Care during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Emergency Care and Medicine. 2024; 1(2):176-192. https://doi.org/10.3390/ecm1020019

Chicago/Turabian StyleNash, Carol. 2024. "Burnout in Medical Specialists Redeployed to Emergency Care during the COVID-19 Pandemic" Emergency Care and Medicine 1, no. 2: 176-192. https://doi.org/10.3390/ecm1020019

APA StyleNash, C. (2024). Burnout in Medical Specialists Redeployed to Emergency Care during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Emergency Care and Medicine, 1(2), 176-192. https://doi.org/10.3390/ecm1020019