Liposomes as “Trojan Horses” in Cancer Treatment: Design, Development, and Clinical Applications

Abstract

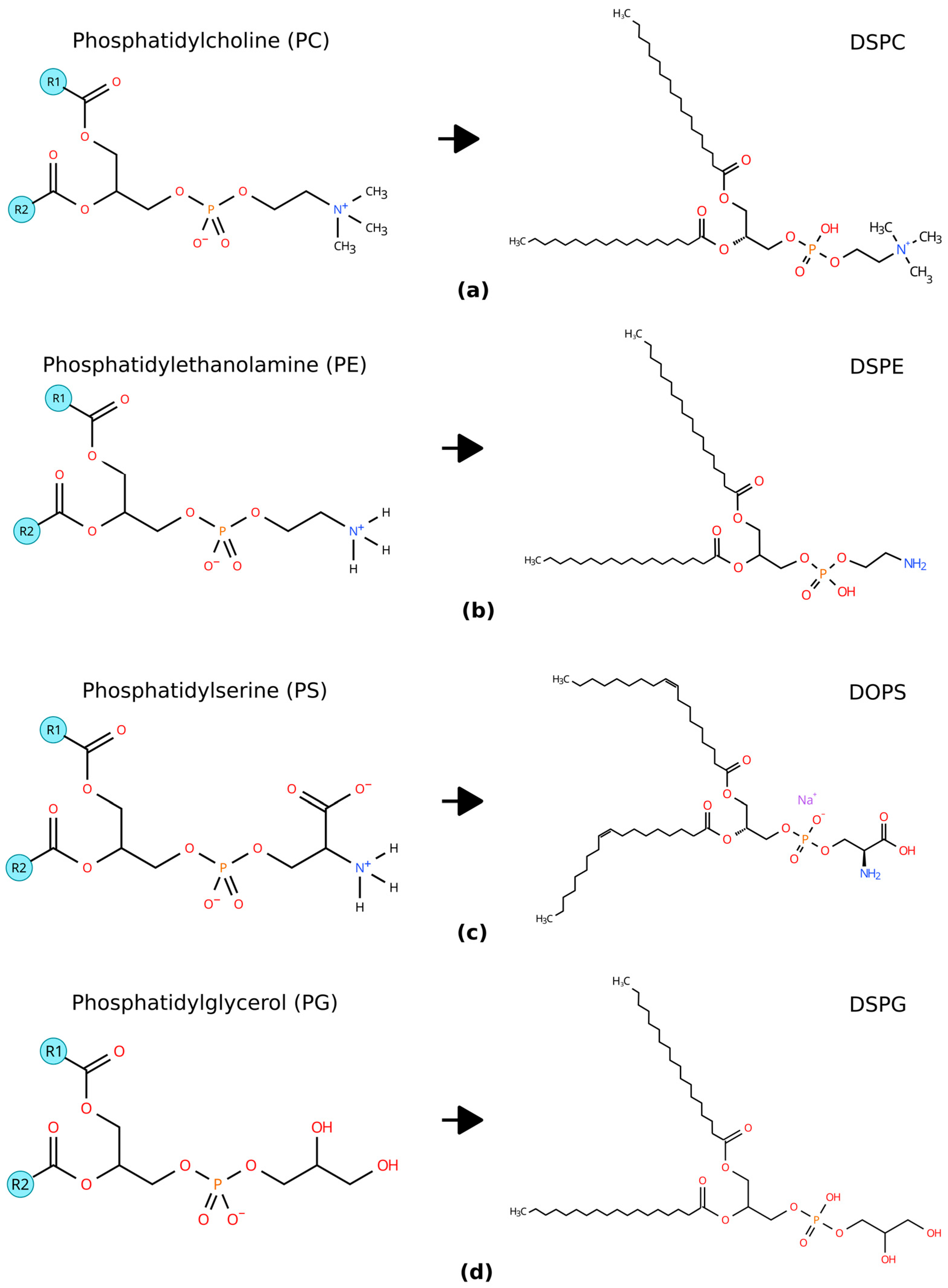

1. What Are Liposomes?

2. Preparation Methods

3. Drug Loading Methods

3.1. Passive Loading Methods

3.2. Active Loading Methods

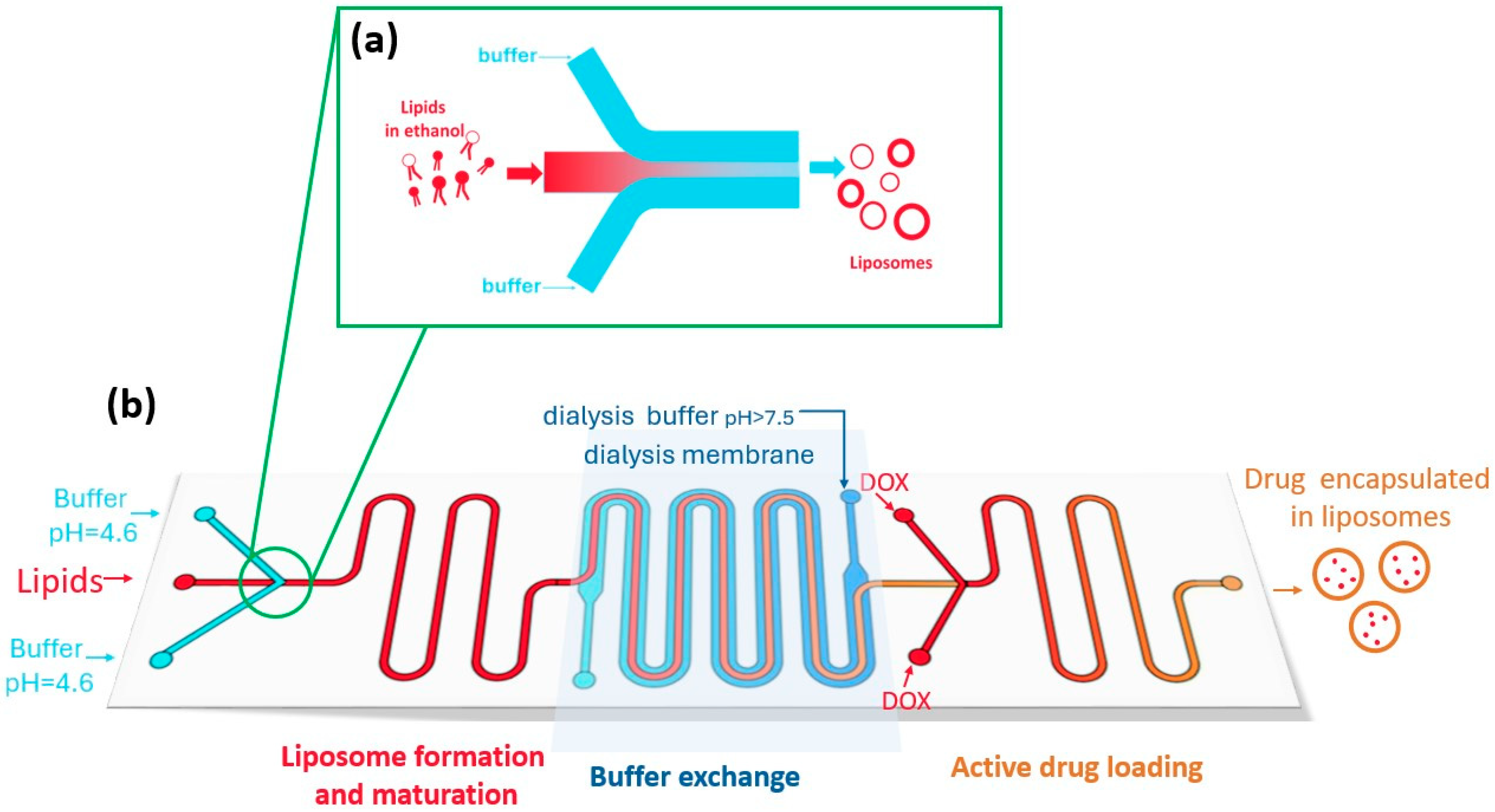

3.3. Microfluidic Methods

4. Circulation and Stability

4.1. Stability

4.2. Cholesterol

4.3. Size

4.4. PEG-Ylation

5. Targeting

5.1. Passive Targeting: Enhanced Permeation and Retention (EPR)

5.2. Active Targeting

5.2.1. Antibody–Liposome Bioconjugates (Immunoliposomes)

5.2.2. Aptamers

5.2.3. Sensitive Liposomes

6. Approved Liposomal Formulations for Cancer Treatment

| Commercial Name | Doxil/Caelyx | DaunoXome | DepoCyte | Myocet |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Manufacturer | Baxter Healthcare Corporation (Deerfield, US) Janssen Pharmaceutica (Beerse, Belgium) | NeXstar Pharmaceutical (Boulder, US) | Pacira Ltd. (Watford, UK) | GP-Pharm (L’Hospitalet de Llobregat, Spain) Sun pharmaceutical (Mumbai, India) |

| Approval date | 1995 (US, Doxil) 1996 (EU, Caelix) | 1996 (US) | 1999 (US) 2001 (EU) | 2000 (US and EU) |

| Illness | Breast, Ovarian, Kaposi’s sarcoma (KS), and Multiple Myeloma | HIV-associated KS | Lymphomatous meningitis | Breast cancer |

| API | DOX Hydrochloride | Daunorubicin citrate | Cytarabine | DOX hydrochloride |

| Composition | MPEG-2000-DSPE:HSPC:Chol (5:55:40) | DSPC:Chol (2:1) | DOPC:DPPC:triolein:Chol | EPC:Chol (45:55) |

| Drug loading | Active (pH gradient of ammonium sulfate) | Passive | Passive | Active (pH-gradient with citrate buffer) |

| Preparation Method | Thin-film hydration + extrusion | Thin-film hydration + extrusion | DepoFoam technique | Thin-film hydration + extrusion |

| Stability (Particle Size, Zeta Potential, and Tc) | 100 nm (Unilamellar); 55 °C | 48–80 nm (Unilamellar); −5 mV | 20 µm (Multilamellar) | 150–250 nm (Unilamellar); −10 to −20 mV |

| Circulation profile | The half-life up to 231 h, with a mean of 73.9 h due to PEGylation, avoiding RES | Prolonged circulation due to small size, avoiding RES and phagocytosis Non-PEGylated | Cytotoxic drug concentrations in the cerebro-spinal fluid (CSF) are maintained up to 14 days | Larger size leads to faster recognition by RES, yet in vivo assays show extended circulation time Non-PEGylated |

| Targeting | Passive (EPR) | Passive (EPR) | Direct injection into the CSF compartment | Passive (EPR) |

| Drug release | Controlled by cholesterol; mechanism not fully understood | Sustained intracellular release over ≥36 h, maintaining cytotoxic levels within tumor cells | Liposome degradation | Passive release |

| Observations | Avoiding heart damage risk of free DOX | Suitable for tumors with high vascular permeability No longer marketed | No longer marketed | Low systemic toxicity. Reduced incidence of cardiac events and congestive heart failure compared to free DOX |

| References | [109,117,118,119] | [110,120,121,122,123] | [118,124,125] | [126,127] |

| Commercial name | Lipusu | Mepact | Marqibo | Onivyde |

| Manufacturer | Nanjing Luye Pharmaceutical (Shanghai, China) | Takeda France (Courbevoie, France) | Talon Therapeutics (San Francisco, US) | Merrimack Pharmaceuticals (Cambridge, US) |

| Approval date | 2006 (China) | 2009 (EU) | 2012 (US) | 2015 (US) 2016 (EU) |

| Illness | Breast, ovarian, and lung cancer | Osteosarcoma | Leukemia | Pancreatic cancer |

| API | Paclitaxel | Mifamurtide | Vincristine Sulfate (VCR) | Irinotecan HCL trihydrate |

| Composition | Lecithin–Chol | DOPS:POPC (3:7) | SM:Chol (60:40) | DSPC:Chol:MPEG-2000-DSPE (3:2:0.015) |

| Drug loading | Passive | Passive | Active (pH gradient) | Active (with triethylammonium sucrose octasulfate) |

| Preparation Method | Thin-film hydration + extrusion | In situ, mixed with 0.9% saline solution. | Ethanol injection + extrusion | Ethanol injection + extrusion |

| Stability (Particle Size, Zeta Potential and Tc) | <200 nm (Unilamellar) | 2–3.5 µm (Multilamellar) 5 °C | 130–150 nm (Unilamellar) | ~110 nm (Unilamellar); –18 mV; 55 °C |

| Circulation profile | Rapidly cleared from serum with half-life of 2 h | Low protein binding, which results in a prolonged circulation time for the liposome Non-PEGylated | Long circulation time due to PEGylation, avoiding RES | |

| Targeting | Passive (EPR) | Targeting immune system for immunotherapy | Passive (EPR) | Passive (EPR) |

| Drug release | Liposome degradation | Long release half-time, up to 117 h | Prolonged release; half-life of drug release up to 56.8 h | |

| Observations | First paclitaxel liposome commercial in China | Used in children and young adults after resection surgery | No longer marketed | Improved tumor accumulation |

| References | [92] | [118,128,129,130,131] | [32,132] | [133,134,135] |

| Commercial name | Vyxeos | Celdoxome | Zolsketil | |

| Manufacturer | Jazz Pharmaceuticals (Dublin, Ireland) | Baxter Holding (Utrecht, Netherlands) | Accord Healthcare (Barcelona, Spain) | |

| Approval date | 2017 (US) 2018 (EU) | 2022 (EU) | 2022 (EU) | |

| Illness | Myeloid leukemia | Breast, ovarian, Kaposi’s sarcoma, and Multiple Myeloma | Breast, ovarian neoplasms, and Kaposi’s sarcoma | |

| API | Daunorubicin, cytarabine (1:5) | DOX hydrochloride | DOX hydrochloride | |

| Composition | DSPC:DSPG:Chol (7:2:1) | MPEG-2000-DSPE:HSPC:Chol | MPEG-2000-DSPE:HSPC:Chol | |

| Drug loading | Passive + active (with copper gluconate buffer) | Active (pH gradient of ammonium sulfate) | Active (pH gradient of ammonium sulfate) | |

| Preparation Method | Thin-film hydration + extrusion | Thin-film hydration + extrusion | Thin-film hydration + extrusion | |

| Stability (Particle Size, Zeta Potential and Tc) | 107 nm (bilamellar) –33 mV 55.3 °C | 75–100 nm (Unilamellar) 55 °C | 75–100 nm (Unilamellar) 55 °C | |

| Circulation profile | ~50× longer circulation time than free drug Uses anionic phosphtildylgrlycerol as alternative to PEG to avoid ABC phenomenon | The half-life up to 231 h, with a mean of 73.9 h due to PEGylation, avoiding RES | Long circulation times. With an average half-time of 73.9 h | |

| Targeting | Preferential internalization of CPX-351 liposomes | Passive (EPR) | Passive (EPR) | |

| Drug release | Low cholesterol optimized for tumor-controlled release | Passive release | ||

| Observations | Dual-drug formulation with a fixed synergistic ratio; in vivo efficacy is drug ratio-dependent Potentially avoids P-gp-mediated efflux, reducing treatment resistance | Authorized as generic | Bioequivalent to Caelyx | |

| References | [136] | [137] | [138,139] | |

7. Future Trends

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DSPE | 1,2-Distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine |

| PC | Phosphatidylcholine |

| PE | Phosphatidylethanolamine |

| PS | Phosphatidylserine |

| PG | Phosphatidylglycerol |

| PEG | Polyethylene Glycol |

| Tc | Transition Temperature |

| DSPC | 2-Distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine |

| DMPC | Dimyristoylphosphatidylcholine |

| DPPC | Dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholine |

| DSPG | Distearoyl phosphatidylglycerol |

| DOPC | 1,2-Dioleoyl-sn-Glycero-3-Phosphocholine |

| DMPE | Dimyristoylphosphatidylethanolamine |

| HSPC | Hydrogenated soybean phosphatidylcholine |

| DOTAP | 1,2-dioleoyl-3-trimethylammoniumpropane |

| Chol | Cholesterol |

| CHEMS | Cholesterol Hemisuccinate |

| POPC | 1-Palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine |

| DOPS | 1,2-Dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-L-serine sodium salt |

| SM | Sphingomyelins |

| MLV | Large Multilamellar Vesicles |

| REV | Reverse-Phase Evaporation |

| EE% | Encapsulation Efficiency |

| SEC | Size-Exclusion Chromatography |

| HPLC | High-Performance Liquid Chromatography |

| NMR | Nuclear Magnetic Resonance |

| DOX | Doxorubicin |

| EPC | Egg Phosphatidylcholine |

| DLVO | Derjaguin–Landau–Verwey–Overbeek |

| RES | Reticuloendothelial System |

| ABC | Accelerated Blood Clearance |

| EPR | Enhanced Permeation and Retention |

| VEGF | Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration |

| NSCLC | Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer |

| HER | Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor |

| MMPS | Targeting Matrix Metalloproteinases |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic Acid |

| RNA | Ribonucleic Acid |

| RFA | Radiofrequency Ablation |

| HIFU | High-Intensity Focused Ultrasound |

| EMA | European Medicine Agency |

| US | United States |

| EU | European Union |

| KS | Kaposi’s Sarcoma |

| CSF | Cerebro-Spinal Fluid |

| NK | Natural Killer |

| MRSA | Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus |

| BBB | Blood–Brain Barrier |

| PTT | Photothermal Therapy |

| TME | Tumor Microenvironment |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| ML | Machine Learning |

References

- Bangham, A.D.; Horne, R.W. Negative Staining of Phospholipids and Their Structural Modification by Surface-Active Agents as Observed in the Electron Microscope. J. Mol. Biol. 1964, 8, 660–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bozzuto, G.; Molinari, A. Liposomes as Nanomedical Devices. Int. J. Nanomed. 2015, 10, 975–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gregoriadis, G. Liposomes in Drug Delivery: How it All Happened. Pharmaceutics 2016, 8, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, L.K.; Vance, J.E.; Vance, D.E. Phosphatidylcholine Biosynthesis and Lipoprotein Metabolism. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 2012, 1821, 754–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pentak, D. Alternative Methods of Determining Phase Transition Temperatures of Phospholipids that Constitute Liposomes on the Example of DPPC and DMPC. Thermochim. Acta 2014, 584, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attwood, S.J.; Choi, Y.; Leonenko, Z. Preparation of DOPC and DPPC Supported Planar Lipid Bilayers for Atomic Force Microscopy and Atomic Force Spectroscopy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 3514–3539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Duša, F.; Witos, J.; Ruokonen, S.-K.; Wiedmer, S.K. Determination of the Main Phase Transition Temperature of Phospholipids by Nanoplasmonic Sensing. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 14815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvius, J.R.; Mak, N.; McElhaney, R.N. Lipid and Protein Composition and Thermotropic Lipid Phase Transitions in Fatty Acid-Homogeneous Membranes of Acholeplasma laidlawii B. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA Biomembr. 1980, 597, 199–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitayama, H.; Takechi, Y.; Tamai, N.; Matsuki, H.; Yomota, C.; Saito, H. Thermotropic Phase Behavior of Hydrogenated Soybean Phosphatidylcholine–Cholesterol Binary Liposome Membrane. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2014, 62, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pubchem. DOTAP. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/6437371 (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Pubchem. Cholesterol. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/5997 (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- Pubchem. Cholesteryl Hemisuccinate. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/65082 (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- Pubchem. 1-Palmitoyl-2-Oleoyl-Sn-Glycero-3-Phosphocholine. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/5497103 (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- Jiménez-Monreal, A.M.; Villalaín, J.; Aranda, F.J.; Gómez-Fernández, J.C. The Phase Behavior of Aqueous Dispersions of Unsaturated Mixtures of Diacylglycerols and Phospholipids. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA Biomembr. 1998, 1373, 209–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pubchem. 1,2-Dioleoyl-Sn-Glycero-3-Phospho-L-Serine Sodium Salt. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/57369815 (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- Pubchem. MPEG-2000-DSPE. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/86278269 (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- Sphingomyelins. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/44176376 (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- Xiang, B.; Cao, D.-Y. Preparation of Drug Liposomes by Thin-Film Hydration and Homogenization. In Liposome-Based Drug Delivery Systems; Lu, W.-L., Qi, X.-R., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 1–11. ISBN 978-3-662-49231-4. [Google Scholar]

- Pick, U. Liposomes with a Large Trapping Capacity Prepared by Freezing and Thawing of Sonicated Phospholipid Mixtures. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1981, 212, 186–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batzri, S.; Korn, E.D. Single Bilayer Liposomes Prepared without Sonication. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA Biomembr. 1973, 298, 1015–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szoka, F.; Papahadjopoulos, D. Procedure for Preparation of Liposomes with Large Internal Aqueous Space and High Capture by Reverse-Phase Evaporation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1978, 75, 4194–4198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, A.P.; Xu, X.; Burgess, D.J. Freeze-Anneal-Thaw Cycling of Unilamellar Liposomes: Effect on Encapsulation Efficiency. Pharm. Res. 2014, 31, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouda, A.; Sakr, O.S.; Nasr, M.; Sammour, O. Ethanol Injection Technique for Liposomes Formulation: An Insight into Development, Influencing Factors, Challenges and Applications. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2021, 61, 102174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardo, D.; Kiselev, M.A. Methods of Liposomes Preparation: Formation and Control Factors of Versatile Nanocarriers for Biomedical and Nanomedicine Application. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaikwad, V.L.; Choudhari, P.B.; Bhatia, N.M.; Bhatia, M.S. Characterization of Pharmaceutical Nanocarriers: In Vitro and in Vivo Studies. In Nanomaterials for Drug Delivery and Therapy; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 33–58. ISBN 978-0-12-816505-8. [Google Scholar]

- ElMeshad, A.N.; Mortazavi, S.M.; Mozafari, M.R. Formulation and Characterization of Nanoliposomal 5-Fluorouracil for Cancer Nanotherapy. J. Liposome Res. 2014, 24, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panwar, P.; Pandey, B.; Lakhera, P.C.; Singh, K.P. Preparation, Characterization, and in Vitro Release Study of Albendazole-Encapsulated Nanosize Liposomes. Int. J. Nanomed. 2010, 5, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.-M.; Patel, A.B.; De Graaf, R.A.; Behar, K.L. Determination of Liposomal Encapsulation Efficiency Using Proton NMR Spectroscopy. Chem. Phys. Lipids 2004, 127, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, B.; Chiu, D.T. Determination of the Encapsulation Efficiency of Individual Vesicles Using Single-Vesicle Photolysis and Confocal Single-Molecule Detection. Anal. Chem. 2005, 77, 2770–2776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akbarzadeh, A.; Rezaei-Sadabady, R.; Davaran, S.; Joo, S.W.; Zarghami, N.; Hanifehpour, Y.; Samiei, M.; Kouhi, M.; Nejati-Koshki, K. Liposome: Classification, Preparation, and Applications. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2013, 8, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maritim, S.; Boulas, P.; Lin, Y. Comprehensive Analysis of Liposome Formulation Parameters and Their Influence on Encapsulation, Stability and Drug Release in Glibenclamide Liposomes. Int. J. Pharm. 2021, 592, 120051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, M.J.W.; Semple, S.C.; Klimuk, S.K.; Edwards, K.; Eisenhardt, M.L.; Leng, E.C.; Karlsson, G.; Yanko, D.; Cullis, P.R. Therapeutically Optimized Rates of Drug Release Can Be Achieved by Varying the Drug-to-Lipid Ratio in Liposomal Vincristine Formulations. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2006, 1758, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kono, K.; Takashima, M.; Yuba, E.; Harada, A.; Hiramatsu, Y.; Kitagawa, H.; Otani, T.; Maruyama, K.; Aoshima, S. Multifunctional Liposomes Having Target Specificity, Temperature-Triggered Release, and near-Infrared Fluorescence Imaging for Tumor-Specific Chemotherapy. J. Control. Release 2015, 216, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindner, L.H.; Hossann, M. Factors Affecting Drug Release from Liposomes. Curr. Opin. Drug Discov. Devel. 2010, 13, 111–123. [Google Scholar]

- Torchilin, V.P. Multifunctional Nanocarriers. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2006, 58, 1532–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyagi, N.; Rathore, S.S.; Ghosh, P.C. Efficacy of Liposomal Monensin on the Enhancement of the Antitumour Activity of Liposomal Ricin in Human Epidermoid Carcinoma (KB) Cells. Indian J. Pharm. Sci. 2013, 75, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogawa, C.; Liu, Y.-J.; Kobayashi, K.S. Muramyl Dipeptide and Its Derivatives: Peptide Adjuvant in Immunological Disorders and Cancer Therapy. Curr. Bioact. Compd. 2011, 7, 180–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyers, P.A. Muramyl Tripeptide-Phosphatidyl Ethanolamine Encapsulated in Liposomes (L-MTP-PE) in the Treatment of Osteosarcoma. In Current Advances in Osteosarcoma; Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; Volume 804, pp. 307–321. ISBN 978-3-319-04842-0. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, L.D.; Bally, M.B.; Cullis, P.R. Uptake of Adriamycin into Large Unilamellar Vesicles in Response to a pH Gradient. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA Biomembr. 1986, 857, 123–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bally, M.B.; Mayer, L.D.; Loughrey, H.; Redelmeier, T.; Madden, T.D.; Wong, K.; Harrigan, P.R.; Hope, M.J.; Cullis, P.R. Dopamine Accumulation in Large Unilamellar Vesicle Systems Induced by Transmembrane Ion Gradients. Chem. Phys. Lipids 1988, 47, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haran, G.; Cohen, R.; Bar, L.K.; Barenholz, Y. Transmembrane Ammonium Sulfate Gradients in Liposomes Produce Efficient and Stable Entrapment of Amphipathic Weak Bases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA Biomembr. 1993, 1151, 201–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gubernator, J. Active Methods of Drug Loading into Liposomes: Recent Strategies for Stable Drug Entrapment and Increased in Vivo Activity. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2011, 8, 565–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clerc, S.; Barenholz, Y. Loading of Amphipathic Weak Acids into Liposomes in Response to Transmembrane Calcium Acetate Gradients. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA Biomembr. 1995, 1240, 257–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carugo, D.; Bottaro, E.; Owen, J.; Stride, E.; Nastruzzi, C. Liposome Production by Microfluidics: Potential and Limiting Factors. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 25876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jahn, A.; Stavis, S.M.; Hong, J.S.; Vreeland, W.N.; DeVoe, D.L.; Gaitan, M. Microfluidic Mixing and the Formation of Nanoscale Lipid Vesicles. ACS Nano 2010, 4, 2077–2087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahn, A.; Vreeland, W.N.; DeVoe, D.L.; Locascio, L.E.; Gaitan, M. Microfluidic Directed Formation of Liposomes of Controlled Size. Langmuir 2007, 23, 6289–6293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liu, J.; Wang, P.; DeMello, A.; Feng, L.; Zhu, X.; Wen, W.; Kodzius, R.; Gong, X. Synthesis of Biomaterials Utilizing Microfluidic Technology. Genes 2018, 9, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamano, N.; Böttger, R.; Lee, S.E.; Yang, Y.; Kulkarni, J.A.; Ip, S.; Cullis, P.R.; Li, S.-D. Robust Microfluidic Technology and New Lipid Composition for Fabrication of Curcumin-Loaded Liposomes: Effect on the Anticancer Activity and Safety of Cisplatin. Mol. Pharm. 2019, 16, 3957–3967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hood, R.R.; Vreeland, W.N.; DeVoe, D.L. Microfluidic Remote Loading for Rapid Single-Step Liposomal Drug Preparation. Lab. Chip 2014, 14, 3359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkionis, L.; Aojula, H.; Harris, L.K.; Tirella, A. Microfluidic-Assisted Fabrication of Phosphatidylcholine-Based Liposomes for Controlled Drug Delivery of Chemotherapeutics. Int. J. Pharm. 2021, 604, 120711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Sun, J. Lipid in Chips: A Brief Review of Liposomes Formation by Microfluidics. Int. J. Nanomed. 2021, 16, 7391–7416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, C.; Khadke, S.; Tandrup Schmidt, S.; Roces, C.B.; Forbes, N.; Berrie, G.; Perrie, Y. The Impact of Solvent Selection: Strategies to Guide the Manufacturing of Liposomes Using Microfluidics. Pharmaceutics 2019, 11, 653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A. Liposomes in Drug Delivery: Progress and Limitations. Int. J. Pharm. 1997, 154, 123–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grit, M.; De Smidt, J.H.; Struijke, A.; Crommelin, D.J.A. Hydrolysis of Phosphatidylcholine in Aqueous Liposome Dispersions. Int. J. Pharm. 1989, 50, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leuti, A.; Fazio, D.; Fava, M.; Piccoli, A.; Oddi, S.; Maccarrone, M. Bioactive Lipids, Inflammation and Chronic Diseases. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2020, 159, 133–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heurtault, B. Physico-Chemical Stability of Colloidal Lipid Particles. Biomaterials 2003, 24, 4283–4300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuidam, N.J.; Gouw, H.K.M.E.; Barenholz, Y.; Crommelin, D.J.A. Physical (in) Stability of Liposomes upon Chemical Hydrolysis: The Role of Lysophospholipids and Fatty Acids. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA Biomembr. 1995, 1240, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.; Xu, L.; Porter, N.A. Free Radical Lipid Peroxidation: Mechanisms and Analysis. Chem. Rev. 2011, 111, 5944–5972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grit, M.; Crommelin, D.J.A. Chemical Stability of Liposomes: Implications for Their Physical Stability. Chem. Phys. Lipids 1993, 64, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayala, A.; Muñoz, M.F.; Argüelles, S. Lipid Peroxidation: Production, Metabolism, and Signaling Mechanisms of Malondialdehyde and 4-Hydroxy-2-Nonenal. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2014, 2014, 360438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabín, J.; Vázquez-Vázquez, C.; Prieto, G.; Bordi, F.; Sarmiento, F. Double Charge Inversion in Polyethylenimine-Decorated Liposomes. Langmuir 2012, 28, 10534–10542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabín, J.; Prieto, G.; Sennato, S.; Ruso, J.M.; Angelini, R.; Bordi, F.; Sarmiento, F. Effect of Gd 3 + on the Colloidal Stability of Liposomes. Phys. Rev. E 2006, 74, 031913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabín, J.; Prieto, G.; Ruso, J.M.; Messina, P.; Sarmiento, F. Aggregation of Liposomes in Presence of La3+: A Study of the Fractal Dimension. Phys. Rev. E 2007, 76, 011408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabín, J.; Prieto, G.; Sarmiento, F. Stable Clusters in Liposomic Systems. Soft Matter 2012, 8, 3212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, C.; Aranda, F.J.; Ortiz, A.; Martínez, V.; Carvajal, M.; Teruel, J.A. Molecular Aspects of the Interaction between Plants Sterols and DPPC Bilayers. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2011, 358, 192–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briuglia, M.-L.; Rotella, C.; McFarlane, A.; Lamprou, D.A. Influence of Cholesterol on Liposome Stability and on in Vitro Drug Release. Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 2015, 5, 231–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semple, S.C.; Chonn, A.; Cullis, P.R. Influence of Cholesterol on the Association of Plasma Proteins with Liposomes. Biochemistry 1996, 35, 2521–2525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, C.; Jefferies, C.; Cryan, S.-A. Targeted Liposomal Drug Delivery to Monocytes and Macrophages. J. Drug Deliv. 2011, 2011, 727241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, K.; Wang, X.U.; Nie, S.; Chen, Z.; Shin, D.M. Therapeutic Nanoparticles for Drug Delivery in Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2008, 14, 1310–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabín, J.; Prieto, G.; Estelrich, J.; Sarmiento, F.; Costas, M. Insertion of Semifluorinated Diblocks on DMPC and DPPC Liposomes. Influence on the Gel and Liquid States of the Bilayer. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2010, 348, 388–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez-Arca, V.; Sabín, J.; García-Río, L.; Bastos, M.; Taboada, P.; Barbosa, S.; Prieto, G. On the Structure and Stability of Novel Cationic DPPC Liposomes Doped with Gemini Surfactants. J. Mol. Liq. 2022, 366, 120230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foteini, P.; Pippa, N.; Naziris, N.; Demetzos, C. Physicochemical Study of the Protein–Liposome Interactions: Influence of Liposome Composition and Concentration on Protein Binding. J. Liposome Res. 2019, 29, 313–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klibanov, A.L.; Maruyama, K.; Torchilin, V.P.; Huang, L. Amphipathic Polyethyleneglycols Effectively Prolong the Circulation Time of Liposomes. FEBS Lett. 1990, 268, 235–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Z.; Fisher, A.; Liu, W.K.; Li, Y. PEGylated “Stealth” Nanoparticles and Liposomes. In Engineering of Biomaterials for Drug Delivery Systems; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 1–26. ISBN 978-0-08-101750-0. [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed, M.; Abu Lila, A.S.; Shimizu, T.; Alaaeldin, E.; Hussein, A.; Sarhan, H.A.; Szebeni, J.; Ishida, T. PEGylated Liposomes: Immunological Responses. Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 2019, 20, 710–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishida, T.; Kiwada, H. Accelerated Blood Clearance (ABC) Phenomenon upon Repeated Injection of PEGylated Liposomes. Int. J. Pharm. 2008, 354, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dams, E.T.; Laverman, P.; Oyen, W.J.; Storm, G.; Scherphof, G.L.; van Der Meer, J.W.; Corstens, F.H.; Boerman, O.C. Accelerated Blood Clearance and Altered Biodistribution of Repeated Injections of Sterically Stabilized Liposomes. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2000, 292, 1071–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Lai, S.K. Anti-PEG Immunity: Emergence, Characteristics, and Unaddressed Questions. WIREs Nanomed. Nanobiotechnol. 2015, 7, 655–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sercombe, L.; Veerati, T.; Moheimani, F.; Wu, S.Y.; Sood, A.K.; Hua, S. Advances and Challenges of Liposome Assisted Drug Delivery. Front. Pharmacol. 2015, 6, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumura, Y.; Maeda, H. A New Concept for Macromolecular Therapeutics in Cancer Chemotherapy: Mechanism of Tumoritropic Accumulation of Proteins and the Antitumor Agent Smancs. Cancer Res. 1986, 46, 6387–6392. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wu, J. The Enhanced Permeability and Retention (EPR) Effect: The Significance of the Concept and Methods to Enhance Its Application. J. Pers. Med. 2021, 11, 771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabizon, A.; Shmeeda, H.; Barenholz, Y. Pharmacokinetics of Pegylated Liposomal Doxorubicin: Review of Animal and Human Studies. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2003, 42, 419–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guimarães, D.; Cavaco-Paulo, A.; Nogueira, E. Design of Liposomes as Drug Delivery System for Therapeutic Applications. Int. J. Pharm. 2021, 601, 120571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conde, J.; Dias, J.T.; Grazú, V.; Moros, M.; Baptista, P.V.; De La Fuente, J.M. Revisiting 30 Years of Biofunctionalization and Surface Chemistry of Inorganic Nanoparticles for Nanomedicine. Front. Chem. 2014, 2, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabín, J.; Alatorre-Meda, M.; Miñones, J.; Domínguez-Arca, V.; Prieto, G. New Insights on the Mechanism of Polyethylenimine Transfection and Their Implications on Gene Therapy and DNA Vaccines. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2022, 210, 112219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koning, G.A.; Morselt, H.W.M.; Gorter, A.; Allen, T.M.; Zalipsky, S.; Scherphof, G.L.; Kamps, J.A.A.M. Interaction of Differently Designed Immunoliposomes with Colon Cancer Cells and Kupffer Cells. An in Vitro Comparison. Pharm. Res. 2003, 20, 1249–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fobian, S.-F.; Cheng, Z.; Ten Hagen, T.L.M. Smart Lipid-Based Nanosystems for Therapeutic Immune Induction against Cancers: Perspectives and Outlooks. Pharmaceutics 2021, 14, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sergina, N.V.; Moasser, M.M. The HER Family and Cancer: Emerging Molecular Mechanisms and Therapeutic Targets. Trends Mol. Med. 2007, 13, 527–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eloy, J.O.; Petrilli, R.; Trevizan, L.N.F.; Chorilli, M. Immunoliposomes: A Review on Functionalization Strategies and Targets for Drug Delivery. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2017, 159, 454–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.W.; Hong, K.; Kirpotin, D.B.; Meyer, O.; Papahadjopoulos, D.; Benz, C.C. Anti-HER2 Immunoliposomes for Targeted Therapy of Human Tumors. Cancer Lett. 1997, 118, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Choi, M.-K.; Cui, F.-D.; Kim, J.S.; Chung, S.-J.; Shim, C.-K.; Kim, D.-D. Preparation and Evaluation of Paclitaxel-Loaded PEGylated Immunoliposome. J. Control. Release 2007, 120, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Liang, H.; Li, J.; Shao, Z.; Yang, D.; Bao, J.; Wang, K.; Xi, W.; Gao, Z.; Guo, R.; et al. Paclitaxel Liposome (Lipusu) Based Chemotherapy Combined with Immunotherapy for Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: A Multicenter, Retrospective Real-World Study. BMC Cancer 2024, 24, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Normanno, N.; De Luca, A.; Bianco, C.; Strizzi, L.; Mancino, M.; Maiello, M.R.; Carotenuto, A.; De Feo, G.; Caponigro, F.; Salomon, D.S. Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR) Signaling in Cancer. Gene 2006, 366, 2–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, L.; Kate, P.; Torchilin, V.P. Matrix Metalloprotease 2-Responsive Multifunctional Liposomal Nanocarrier for Enhanced Tumor Targeting. ACS Nano 2012, 6, 3491–3498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.W.; Jeong, H.Y.; Kang, S.J.; Choi, M.J.; You, Y.M.; Im, C.S.; Lee, T.S.; Song, I.H.; Lee, C.G.; Rhee, K.-J.; et al. Cancer-Targeted Nucleic Acid Delivery and Quantum Dot Imaging Using EGF Receptor Aptamer-Conjugated Lipid Nanoparticles. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 9474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Hou, J.; Liu, X.; Guo, Y.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Yang, Z. Nucleolin-Targeting Liposomes Guided by Aptamer AS1411 for the Delivery of siRNA for the Treatment of Malignant Melanomas. Biomaterials 2014, 35, 3840–3850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Bi, X.; Yang, L.; Wu, S.; Yu, Y.; Jiang, B.; Zhang, A.; Lan, K.; Duan, S. Co-Delivery of Paclitaxel and PLK1-Targeted siRNA Using Aptamer-Functionalized Cationic Liposome for Synergistic Anti-Breast Cancer Effects In Vivo. J. Biomed. Nanotechnol. 2019, 15, 1135–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slingerland, M.; Guchelaar, H.-J.; Gelderblom, H. Liposomal Drug Formulations in Cancer Therapy: 15 Years along the Road. Drug Discov. Today 2012, 17, 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagami, T.; Kubota, M.; Ozeki, T. Effective Remote Loading of Doxorubicin into DPPC/Poloxamer 188 Hybrid Liposome to Retain Thermosensitive Property and the Assessment of Carrier-Based Acute Cytotoxicity for Pulmonary Administration. J. Pharm. Sci. 2015, 104, 3824–3832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai, L.-A.; Tsai, P.-J.; Wang, Y.-C.; Wang, Y.-J.; Lo, L.-W.; Yang, C.-S. Thermosensitive Liposomes Entrapping Iron Oxide Nanoparticles for Controllable Drug Release. Nanotechnology 2009, 20, 135101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.M.; Cha, J.M.; Nam, J.; Kim, M.S.; Park, S.-J.; Park, E.S.; Lee, H.; Kim, H.R. Formulation Optimization and In Vivo Proof-of-Concept Study of Thermosensitive Liposomes Balanced by Phospholipid, Elastin-Like Polypeptide, and Cholesterol. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e103116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motamarry, A.; Asemani, D.; Haemmerich, D. Thermosensitive Liposomes. In Liposomes; Catala, A., Ed.; InTech: London, UK, 2017; ISBN 978-953-51-3579-1. [Google Scholar]

- Paliwal, S.R.; Paliwal, R.; Vyas, S.P. A Review of Mechanistic Insight and Application of pH-Sensitive Liposomes in Drug Delivery. Drug Deliv. 2015, 22, 231–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karanth, H.; Murthy, R.S.R. pH-Sensitive Liposomes-Principle and Application in Cancer Therapy. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2007, 59, 469–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zang, X.; Ding, H.; Zhao, X.; Li, X.; Du, Z.; Hu, H.; Qiao, M.; Chen, D.; Deng, Y.; Zhao, X. Anti-EphA10 Antibody-Conjugated pH-Sensitive Liposomes for Specific Intracellular Delivery of siRNA. Int. J. Nanomed. 2016, 11, 3951–3967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reddy, T.L.; Garikapati, K.R.; Reddy, S.G.; Reddy, B.V.S.; Yadav, J.S.; Bhadra, U.; Bhadra, M.P. Simultaneous Delivery of Paclitaxel and Bcl-2 siRNA via pH-Sensitive Liposomal Nanocarrier for the Synergistic Treatment of Melanoma. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 35223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boswell, G.W.; Buell, D.; Bekersky, I. AmBisome (Liposomal Amphotericin B): A Comparative Review. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 1998, 38, 583–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohn, D.E.; Shimp, W.S. The Cost Implications of the Use of Pegylated Liposomal Doxorubicin When Choosing an Anthracycline for the Treatment of Platinum-Resistant Ovarian Cancer: A Low-Value Intervention? Gynecol. Oncol. Rep. 2015, 13, 47–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barenholz, Y. Doxil®—The First FDA-Approved Nano-Drug: Lessons Learned. J. Control. Release 2012, 160, 117–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forssen, E.A. The Design and Development of DaunoXome® for Solid Tumor Targeting in Vivo. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 1997, 24, 133–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujifilm Pharmaceuticals U.S.A., Inc. A Phase 2a Study with Safety Run-In to Evaluate the Safety, Tolerability, and Preliminary Efficacy of FF-10832 Monotherapy or in Combination with Pembrolizumab in Patients with Advanced Solid Tumors; Fujifilm Pharmaceuticals U.S.A., Inc.: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Löhr, J.M.; Haas, S.L.; Bechstein, W.-O.; Bodoky, G.; Cwiertka, K.; Fischbach, W.; Fölsch, U.R.; Jäger, D.; Osinsky, D.; Prausova, J.; et al. Cationic Liposomal Paclitaxel plus Gemcitabine or Gemcitabine Alone in Patients with Advanced Pancreatic Cancer: A Randomized Controlled Phase II Trial. Ann. Oncol. 2012, 23, 1214–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swiss Cancer Institute. TLD-1, a Novel Liposomal Doxorubicin, in Patients with Advanced Solid Tumors: A Multicenter Open-Label Single-Arm Phase I Trial. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38377773/ (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- Huppert, L. Innovative Combination Immunotherapy for Metastatic Triple Negative Breast Cancer (TNBC): A Multicenter, Multi-Arm Translational Breast Cancer Research Consortium Study. Available online: https://www.dana-farber.org/clinical-trials/22-468 (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- InxMed (Shanghai) Co., Ltd. A Multicenter, Randomized, Double-Blind, Phase II Clinical Study of IN10018 in Combination with Pegylated Liposomal Doxorubicin (PLD) vs. Placebo in Combination with PLD for the Treatment of Platinum-Resistant Recurrent Ovarian Cancer. Available online: https://adisinsight.springer.com/trials/700356971 (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- National Cancer Institute. Naples Phase III Randomized Multicentre Trial of Carboplatin + Liposomal Doxorubicin vs. Carboplatin + Paclitaxel in Patients with Ovarian Cancer. 2023. Available online: https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT00326456?tab=table (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- Strother, R.; Matei, D. Pegylated Liposomal Doxorubicin in Ovarian Cancer. Ther. Clin. Risk Manag. 2009, 5, 639–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Chen, G.; Zhang, J. A Review of Liposomes as a Drug Delivery System: Current Status of Approved Products, Regulatory Environments, and Future Perspectives. Molecules 2022, 27, 1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roces, C.B.; Port, E.C.; Daskalakis, N.N.; Watts, J.A.; Aylott, J.W.; Halbert, G.W.; Perrie, Y. Rapid Scale-up and Production of Active-Loaded PEGylated Liposomes. Int. J. Pharm. 2020, 586, 119566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collier, M.A.; Bachelder, E.M.; Ainslie, K.M. Electrosprayed Myocet-like Liposomes: An Alternative to Traditional Liposome Production. Pharm. Res. 2017, 34, 419–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magarkar, A.; Dhawan, V.; Kallinteri, P.; Viitala, T.; Elmowafy, M.; Róg, T.; Bunker, A. Cholesterol Level Affects Surface Charge of Lipid Membranes in Saline Solution. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 5005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petre, C.E.; Dittmer, D.P. Liposomal Daunorubicin as Treatment for Kaposi’s Sarcoma. Int. J. Nanomed. 2007, 2, 277–288. [Google Scholar]

- Beltrán-Gracia, E.; López-Camacho, A.; Higuera-Ciapara, I.; Velázquez-Fernández, J.B.; Vallejo-Cardona, A.A. Nanomedicine Review: Clinical Developments in Liposomal Applications. Cancer Nanotechnol. 2019, 10, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi, B.; Mishra, A.P.; Nigam, M.; Kobarfard, F.; Javed, Z.; Rajabi, S.; Khan, K.; Ahsan Ashfaq, H.; Ahmad, T.; Pezzani, R.; et al. Multivesicular Liposome (DepoFoam) in Human Diseases. Iran. J. Pharm. Res. 2020, 19, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez, A.R.; Hidalgo, D.O.; Garrido, R.V.; Sánchez, E.T. Liposomal Cytarabine (DepoCyte®) for the Treatment of Neoplastic Meningitis. Clin. Transl. Oncol. 2005, 7, 232–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swenson, C.E.; Perkins, W.R.; Roberts, P.; Janoff, A.S. Liposome Technology and the Development of MyocetTM (Liposomal Doxorubicin Citrate). Breast 2001, 10, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giodini, L.; Re, F.L.; Campagnol, D.; Marangon, E.; Posocco, B.; Dreussi, E.; Toffoli, G. Nanocarriers in Cancer Clinical Practice: A Pharmacokinetic Issue. Nanomed. Nanotechnol. Biol. Med. 2017, 13, 583–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Medicines Agency (EMA). Mepact. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/mepact (accessed on 22 August 2025).

- Bulbake, U.; Doppalapudi, S.; Kommineni, N.; Khan, W. Liposomal Formulations in Clinical Use: An Updated Review. Pharmaceutics 2017, 9, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Zhao, Q.; Yang, H.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Z.; Gong, Y.; Wan, X. Long-Circulating and Targeted Liposomes Co-Loading Cisplatin and Mifamurtide: Formulation and Delivery in Osteosarcoma Cells. AAPS PharmSciTech 2024, 25, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sone, S.; Utsugi, T.; Tandon, P.; Ogawara, M. A Dried Preparation of Liposomes Containing Muramyl Tripeptide Phosphatidylethanolamine as a Potent Activator of Human Blood Monocytes to the Antitumor State. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 1986, 22, 191–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silverman, J.A.; Deitcher, S.R. Marqibo® (Vincristine Sulfate Liposome Injection) Improves the Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of Vincristine. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2013, 71, 555–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Situ, A.; Kang, Y.; Villabroza, K.R.; Liao, Y.; Chang, C.H.; Donahue, T.; Nel, A.E.; Meng, H. Irinotecan Delivery by Lipid-Coated Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles Shows Improved Efficacy and Safety over Liposomes for Pancreatic Cancer. ACS Nano 2016, 10, 2702–2715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Yang, Z.; Liu, J.; Liu, D.; Wang, Y. Development of a Method to Quantify Total and Free Irinotecan and 7-Ethyl-10-Hydroxycamptothecin (SN-38) for Pharmacokinetic and Bio-Distribution Studies after Administration of Irinotecan Liposomal Formulation. Asian J. Pharm. Sci. 2019, 14, 687–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H. Onivyde for the Therapy of Multiple Solid Tumors. Onco Targets Ther. 2016, 3001–3007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, L.D.; Tardi, P.; Louie, A.C. CPX-351: A Nanoscale Liposomal Co-Formulation of Daunorubicin and Cytarabine with Unique Biodistribution and Tumor Cell Uptake Properties. Int. J. Nanomed. 2019, 14, 3819–3830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Medicines Agency (EMA). Celdoxome Pegylated Liposomal. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/celdoxome-pegylated-liposomal (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Taléns-Visconti, R.; Díez-Sales, O.; De Julián-Ortiz, J.V.; Nácher, A. Nanoliposomes in Cancer Therapy: Marketed Products and Current Clinical Trials. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 4249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Medicines Agency (EMA). Zolsketil Pegylated Liposomal. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/zolsketil-pegylated-liposomal (accessed on 22 August 2025).

- Wang, S.; Chen, Y.; Guo, J.; Huang, Q. Liposomes for Tumor Targeted Therapy: A Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 2643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghebati-Maleki, A.; Dolati, S.; Ahmadi, M.; Baghbanzhadeh, A.; Asadi, M.; Fotouhi, A.; Yousefi, M.; Aghebati-Maleki, L. Nanoparticles and Cancer Therapy: Perspectives for Application of Nanoparticles in the Treatment of Cancers. J. Cell. Physiol. 2020, 235, 1962–1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antimisiaris, S.G.; Marazioti, A.; Kannavou, M.; Natsaridis, E.; Gkartziou, F.; Kogkos, G.; Mourtas, S. Overcoming Barriers by Local Drug Delivery with Liposomes. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2021, 174, 53–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, D.; Cao, Y.; Cao, M.; Wang, Y.; Cao, Y.; Gong, T. Nanomedicine in Cancer Therapy. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.; Dhawan, V.; Holm, R.; Nagarsenker, M.S.; Perrie, Y. Liposomes: Advancements and Innovation in the Manufacturing Process. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2020, 154–155, 102–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.-J.; Liu, X.-Y.; Xing, L.; Wan, X.; Chang, X.; Jiang, H.-L. Fenton Reaction-Independent Ferroptosis Therapy via Glutathione and Iron Redox Couple Sequentially Triggered Lipid Peroxide Generator. Biomaterials 2020, 241, 119911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thi, T.T.H.; Suys, E.J.A.; Lee, J.S.; Nguyen, D.H.; Park, K.D.; Truong, N.P. Lipid-Based Nanoparticles in the Clinic and Clinical Trials: From Cancer Nanomedicine to COVID-19 Vaccines. Vaccines 2021, 9, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenchov, R.; Bird, R.; Curtze, A.E.; Zhou, Q. Lipid Nanoparticles—From Liposomes to mRNA Vaccine Delivery, a Landscape of Research Diversity and Advancement. ACS Nano 2021, 15, 16982–17015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhaliwal, H.K.; Fan, Y.; Kim, J.; Amiji, M.M. Intranasal Delivery and Transfection of mRNA Therapeutics in the Brain Using Cationic Liposomes. Mol. Pharm. 2020, 17, 1996–2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gregoriadis, G. Liposomes and mRNA: Two Technologies Together Create a COVID-19 Vaccine. Med. Drug Discov. 2021, 12, 100104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbo, C.; Molinaro, R.; Taraballi, F.; Toledano Furman, N.E.; Hartman, K.A.; Sherman, M.B.; De Rosa, E.; Kirui, D.K.; Salvatore, F.; Tasciotti, E. Unveiling the in Vivo Protein Corona of Circulating Leukocyte-like Carriers. ACS Nano 2017, 11, 3262–3273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Zhang, N.; Li, Q.; Chen, J.; Wang, Q.; Yang, H.; Tan, H.; Gao, J.; Dong, Z.; Pang, Z.; et al. Biomimetic Liposomes Hybrid with Platelet Membranes for Targeted Therapy of Atherosclerosis. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 408, 127296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Wu, Y.; Sun, M.; Qin, Y.; Zhao, J.; Qiu, Z.; Li, C.; Zhang, Y.; Xiong, Y.; Shen, Y.; et al. Spatiotemporally Sequential Delivery of Biomimetic Liposomes Potentiates Glioma Chemotherapy. J. Control. Release 2024, 365, 876–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Zeng, H.; You, Y.; Wang, R.; Tan, T.; Wang, W.; Yin, L.; Zeng, Z.; Zeng, Y.; Xie, T. Active Targeting of Orthotopic Glioma Using Biomimetic Liposomes Co-Loaded Elemene and Cabazitaxel Modified by Transferritin. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2021, 19, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, E.A.; Omolo, C.A.; Gafar, M.A.; Khan, R.; Nyandoro, V.O.; Yakubu, E.S.; Mackraj, I.; Tageldin, A.; Govender, T. Novel Peptide and Hyaluronic Acid Coated Biomimetic Liposomes for Targeting Bacterial Infections and Sepsis. Int. J. Pharm. 2024, 662, 124493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Dong, X.; Yang, S.; Lai, X.; Liu, H.; Gao, Y.; Feng, H.; Zhu, M.; Yuan, Y.; Lu, Q.; et al. Biomimetic Liposomal Nanoplatinum for Targeted Cancer Chemophototherapy. Adv. Sci. 2021, 8, 2003679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chheda, D.; Shete, S.; Tanisha, T.; Devrao Bahadure, S.; Sampathi, S.; Junnuthula, V.; Dyawanapelly, S. Multifaceted Therapeutic Applications of Biomimetic Nanovaccines. Drug Discov. Today 2024, 29, 103991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, J.; Chen, L.; Li, Z.; Liu, L.; Zeng, R.; He, Y.; Shen, Y.; Zhang, T.; Ding, Y. Multifunctional Biomimetic Liposomes with Improved Tumor-Targeting for TNBC Treatment by Combination of Chemotherapy, Antiangiogenesis and Immunotherapy. Adv. Health. Mater. 2024, 13, 2400046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Gao, D.; Hu, D.; Lan, S.; Liu, Y.; Zheng, H.; Yuan, Z.; Sheng, Z. Delivery of Biomimetic Liposomes via Meningeal Lymphatic Vessels Route for Targeted Therapy of Parkinson’s Disease. Research 2023, 6, 0030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kommineni, N.; Chaudhari, R.; Conde, J.; Tamburaci, S.; Cecen, B.; Chandra, P.; Prasad, R. Engineered Liposomes in Interventional Theranostics of Solid Tumors. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2023, 9, 4527–4557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, M.; Kim, G.; Lee, W.; Baek, S.; Jung, H.N.; Im, H.-J. Development of Theranostic Dual-Layered Au-Liposome for Effective Tumor Targeting and Photothermal Therapy. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2021, 19, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thébault, C.J.; Ramniceanu, G.; Boumati, S.; Michel, A.; Seguin, J.; Larrat, B.; Mignet, N.; Ménager, C.; Doan, B.-T. Theranostic MRI Liposomes for Magnetic Targeting and Ultrasound Triggered Release of the Antivascular CA4P. J. Control. Release 2020, 322, 137–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, R.; Jain, N.K.; Yadav, A.S.; Chauhan, D.S.; Devrukhkar, J.; Kumawat, M.K.; Shinde, S.; Gorain, M.; Thakor, A.S.; Kundu, G.C.; et al. Liposomal Nanotheranostics for Multimode Targeted in Vivo Bioimaging and Near-infrared Light Mediated Cancer Therapy. Commun. Biol. 2020, 3, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Gong, C.; Chen, Z.; Li, M.; Li, Y.; Gao, J. Tumor Microenvironment-Activated Cancer Cell Membrane-Liposome Hybrid Nanoparticle-Mediated Synergistic Metabolic Therapy and Chemotherapy for Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2021, 19, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mockrin, S.C.; Byers, L.D.; Koshland, D.E. Subunit Interactions in Yeast Glyceraldehyde-3-Phosphate Dehydrogenase. Biochemistry 1975, 14, 5428–5437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenblum, D.; Gutkin, A.; Kedmi, R.; Ramishetti, S.; Veiga, N.; Jacobi, A.M.; Schubert, M.S.; Friedmann-Morvinski, D.; Cohen, Z.R.; Behlke, M.A.; et al. CRISPR-Cas9 Genome Editing Using Targeted Lipid Nanoparticles for Cancer Therapy. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eabc9450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sengar, A. The Role of Liposomal Drug Delivery in Modern Medicine and the Expanding Potential of Nanocarriers. Preprints. 2025, 2025031802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sengar, A. Personalized Drug Delivery with Smart Nanotechnology and AI Innovations. Preprints. 2025, 2025032203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Min, J.; Kim, S.; Ko, J. AI-Driven Microphysiological Systems for Advancing Nanoparticle Therapeutics. Adv. Intell. Syst. 2025, 2500022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, Y.; Lin, Y.; Wei, T.; Cheng, Q. Lipid Nanoparticle (LNP) Enables mRNA Delivery for Cancer Therapy. Adv. Mater. 2023, 35, 2303261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraf, S.; Jain, A.; Tiwari, A.; Verma, A.; Panda, P.K.; Jain, S.K. Advances in Liposomal Drug Delivery to Cancer: An Overview. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2020, 56, 101549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, S.; Khurana, S.; Choudhari, R.; Kesari, K.K.; Kamal, M.A.; Garg, N.; Ruokolainen, J.; Das, B.C.; Kumar, D. Specific Targeting Cancer Cells with Nanoparticles and Drug Delivery in Cancer Therapy. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2021, 69, 166–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Component Name | Molecular Formula | Charge | Tc (°C) | Molecular Weight (g/mol) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dimyristoylphosphatidylcholine (DMPC) | C36H72NO8P | 0 | 24 | 678 | [5] |

| Dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholine (DPPC) | C40H80NO8P | 0 | 41 | 734 | [6] |

| Distearoyl phosphatidylcholine (DSPC) | C44H88NO8P | 0 | 55 | 790 | [7] |

| Distearoyl phosphatidylglycerol (DSPG) | C42H83O10P | 0 | 55 | 779 | [8] |

| 1,2-Dioleoyl-sn-Glycero-3-Phosphocholine (DOPC) | C44H84NO8P | 0 | −16.5 | 786 | [6] |

| Dimyristoylphosphatidylethanolamine (DMPE) | C33H66NO8P | 0 | 50 | 635.8 | [8] |

| Distearoylphosphatidylethanolamine (DSPE) | C41H82NO8P | 0 | 74 | 748 | [8] |

| Hydrogenated soybean phosphatidylcholine (HSPC) | C42H84NO8P | 0 | 54 | 762 | [9] |

| 1,2-dioleoyl-3-trimethylammoniumpropane (DOTAP) | C42H80NO4+ | 1 | - | 663 | [10] |

| Cholesterol (Chol) | C27H46O | 0 | - | 386.6 | [11] |

| Cholesterol hemisuccinate (CHEMS) | C31H50O4 | 0 | - | 486.7 | [12] |

| 1-Palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (POPC) | C42H82NO8P | 0 | −7 | 760 | [13,14] |

| 1,2-Dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-L-serine sodium salt (DOPS) | C42H78NO10P | 0 | −11 | 788 | [9,15] |

| MPEG-2000-DSPE | C45H87NNaO11P | 0 | - | 872 | [16] |

| Sphingomyelins (SM) | C24H50N2O6P+ | 1 | - | 493.6 | [17] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sabín, J.; Santisteban-Veiga, A.; Costa-Santos, A.; Abelenda, Ó.; Domínguez-Arca, V. Liposomes as “Trojan Horses” in Cancer Treatment: Design, Development, and Clinical Applications. Lipidology 2025, 2, 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/lipidology2040025

Sabín J, Santisteban-Veiga A, Costa-Santos A, Abelenda Ó, Domínguez-Arca V. Liposomes as “Trojan Horses” in Cancer Treatment: Design, Development, and Clinical Applications. Lipidology. 2025; 2(4):25. https://doi.org/10.3390/lipidology2040025

Chicago/Turabian StyleSabín, Juan, Andrea Santisteban-Veiga, Alba Costa-Santos, Óscar Abelenda, and Vicente Domínguez-Arca. 2025. "Liposomes as “Trojan Horses” in Cancer Treatment: Design, Development, and Clinical Applications" Lipidology 2, no. 4: 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/lipidology2040025

APA StyleSabín, J., Santisteban-Veiga, A., Costa-Santos, A., Abelenda, Ó., & Domínguez-Arca, V. (2025). Liposomes as “Trojan Horses” in Cancer Treatment: Design, Development, and Clinical Applications. Lipidology, 2(4), 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/lipidology2040025