Damage-Associated Molecular Patterns in Perioperative Anesthesia Care: A Clinical Perspective

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

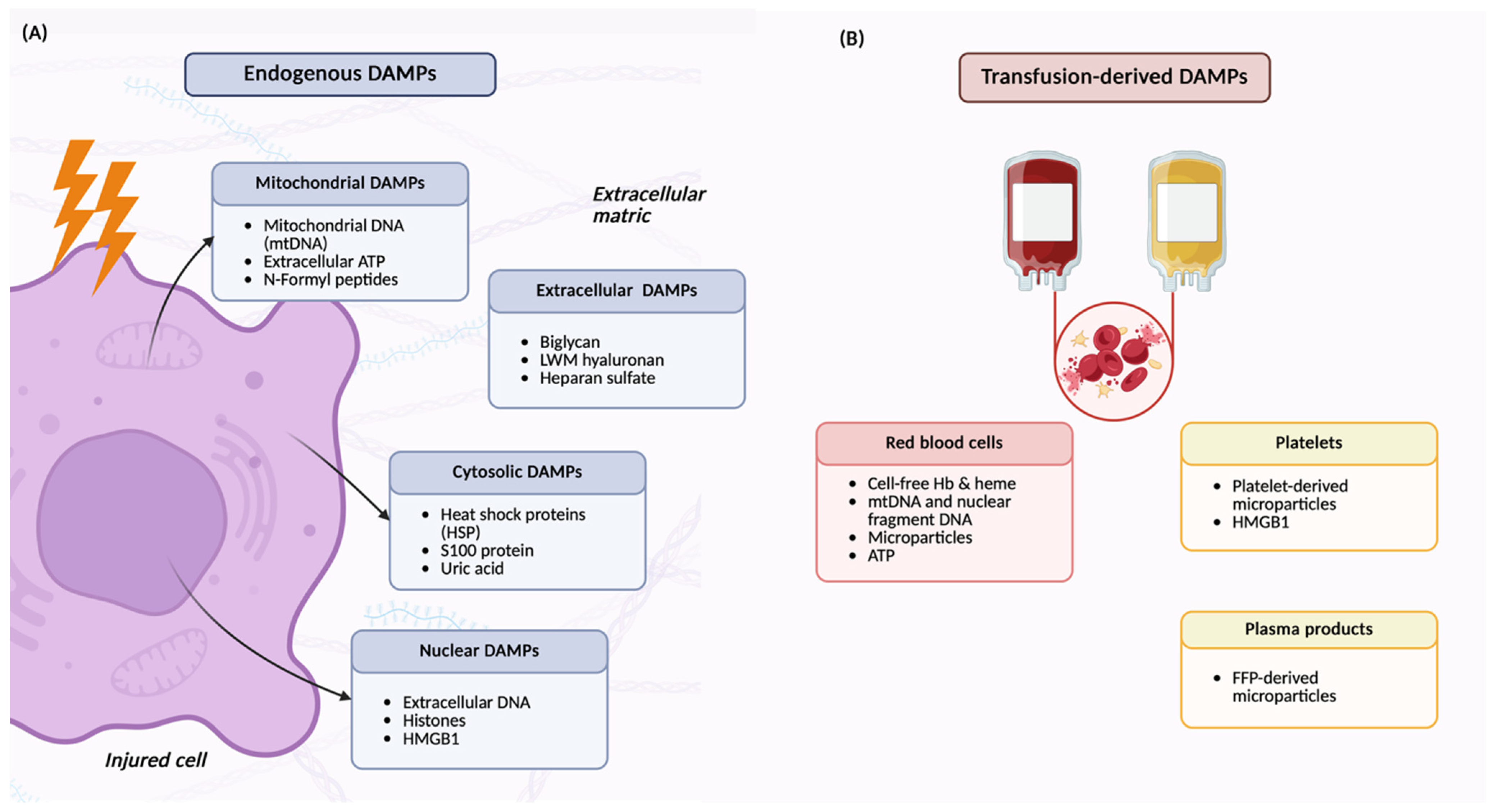

3. Understanding Damage-Associated Molecular Patterns (DAMPs)

3.1. Historical Background and the Danger Model of Immunity

3.2. Perioperative DAMPs and Immune Recognition

3.3. Dual Roles of DAMPs: Healing and Harm

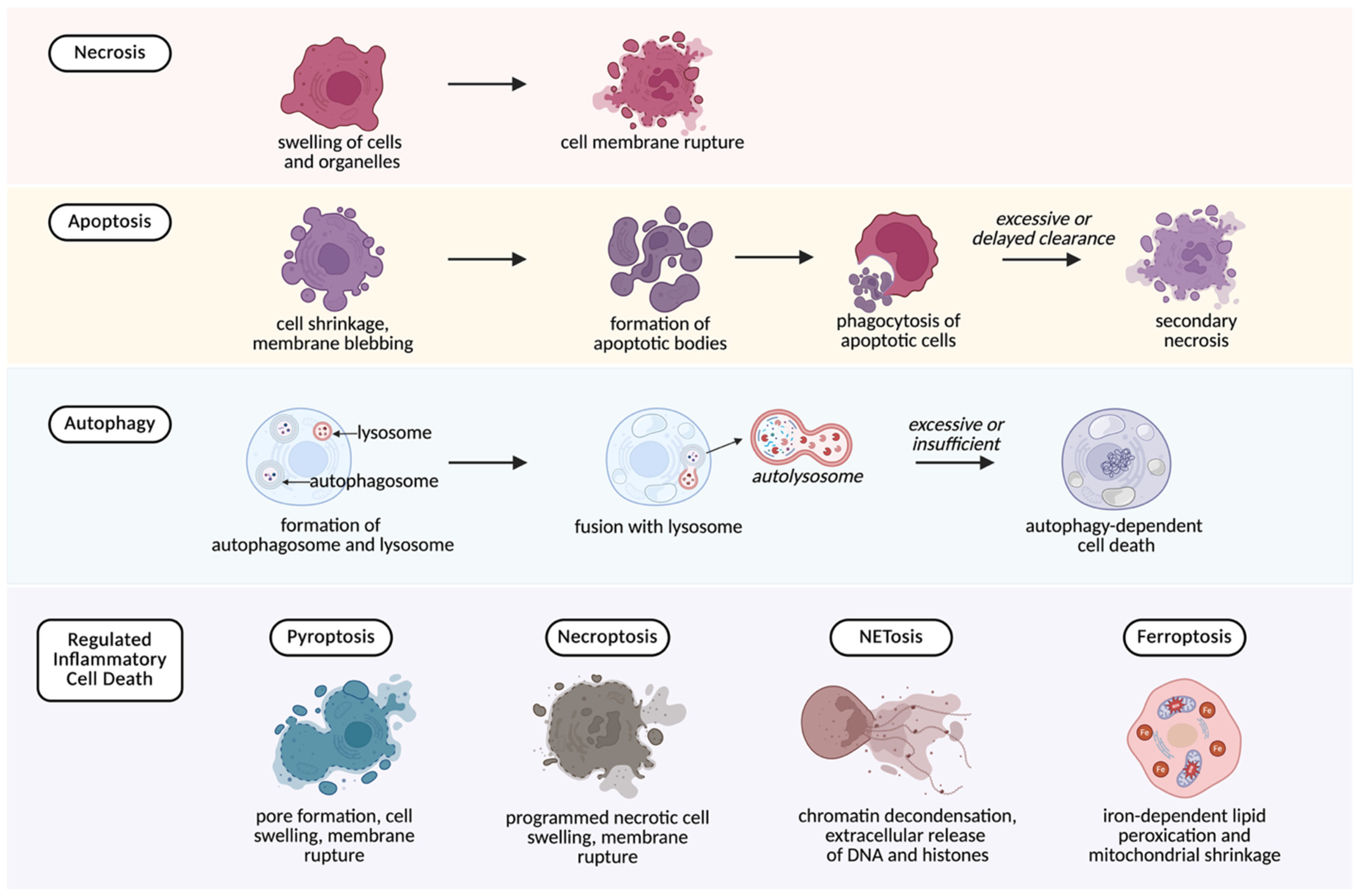

4. Cell Death as a Source of DAMPs

- Necrosis

- Necrosis is an uncontrolled form of cell death that results from direct trauma, ischemia, or toxic injury. It is characterized by cellular swelling and membrane rupture, which cause the release of nuclear, mitochondrial, and cytosolic components into the extracellular space [25]. Necrosis is therefore a major contributor to DAMP release during surgical dissection and manipulation, liberating molecules such as HMGB1, ATP, histones, heat shock proteins (HSPs), mtDNA, and cell-free DNA (cfDNA) [26].

- Apoptosis

- Apoptosis is a tightly regulated process that normally avoids inflammation. Cellular content are packaged into apoptotic bodies that are cleared by phagocytes without DAMP release [27]. However, if clearance is delayed or overwhelmed, apoptotic cells progress to secondary necrosis, resulting in the release of DAMPs, particularly, HMGB1 [28]. Clinically, it has been shown that the rate of apoptosis is significantly increased in patients undergoing surgical stress [29].

- Autophagy-related death

- Autophagy is usually a protective mechanism that helps cells survive stress by removing damaged cytoplasmic components and preserving cellular homeostasis. In the perioperative setting, this function can reduce the release of DAMPs during tissue stress. However, when stress is excessive or prolonged, autophagy may fail and progress to cell death, allowing intracellular material to escape and contribute to extracellular pool of DAMPs [30].

- Regulated inflammatory cell death

- This group of programmed cell death pathways differs from apoptosis in that it provokes inflammation rather than suppressing it. Several regulated inflammatory cell death mechanisms are increasingly recognized as important in perioperative injury:

- ○

- Pyroptosis—a pro-inflammatory form of cell death driven by NLRP3 inflammasome activation. A common trigger is extracellular ATP acting on P2X7 receptors. The process results in membrane rupture and the release of cytokines (IL-1β, IL-18) together with DAMPs, amplifying inflammation [31].

- ○

- Necroptosis—a regulated form of cell death that resembles necrosis in its outcome but proceeds though a regulated signaling cascade. It culminates in membrane disruption and extracellular release of HMGB1, ATP, and S100 proteins [32].

- ○

- Ferroptosis—associated with iron overload and lipid peroxidation, this process releases DAMPs such as HMGB1 and has been implicated in ischemia–reperfusion injury [33].

- ○

- NETosis—a neutrophil-specific pathway in which neutrophils release neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) composed of DNA, histones, and granule proteins. Although NETs immobilize pathogens, they are also rich in DAMPs that promote endothelial injury, thrombosis, and organ dysfunction [34]. NETosis has also been implicated in complications such as transfusion-related lung injury and thromboinflammation [35,36].

5. Perioperative Sources of DAMPs

5.1. Surgical Trauma

5.2. Ischemia–Reperfusion Injury

5.3. Cardiopulmonary Bypass and Extracorporeal Circulation

5.4. Blood Product Transfusion

5.5. Mechanical Ventilation

6. Pathophysiological Consequences of DAMP Release

6.1. Endothelial Activation and Microvascular Dysfunction

6.2. Thrombosis and Coagulopathy

6.3. Propagation of Systemic Inflammation

6.4. Organ Dysfunction

7. Anesthetic Implications

7.1. Anesthetic Agents

7.2. Transfusion Practice

7.3. Cardiopulmonary Bypass and Extracorporeal Circuits

7.4. Ischemia–Reperfusion Injury

7.5. Monitoring and Risk Stratification

8. Future Directions

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Land, W.G. The Role of Damage-Associated Molecular Patterns (DAMPs) in Human Diseases: Part II: DAMPs as diagnostics, prognostics and therapeutics in clinical medicine. Sultan Qaboos Univ. Med. J. 2015, 15, e157–e170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matzinger, P. Tolerance, danger, and the extended family. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 1994, 12, 991–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maisat, W.; Yuki, K. Narrative review of systemic inflammatory response mechanisms in cardiac surgery and immunomodulatory role of anesthetic agents. Ann. Card. Anaesth. 2023, 26, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.Y.; Nuñez, G. Sterile inflammation: Sensing and reacting to damage. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2010, 10, 826–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mogensen, T.H. Pathogen recognition and inflammatory signaling in innate immune defenses. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2009, 22, 240–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janeway, C.A., Jr. The immune system evolved to discriminate infectious nonself from noninfectious self. Immunol. Today 1992, 13, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matzinger, P. The danger model: A renewed sense of self. Science 2002, 296, 301–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Evans, J.E.; Rock, K.L. Molecular identification of a danger signal that alerts the immune system to dying cells. Nature 2003, 425, 516–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scaffidi, P.; Misteli, T.; Bianchi, M.E. Release of chromatin protein HMGB1 by necrotic cells triggers inflammation. Nature 2002, 418, 191–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bianchi, M.E. DAMPs, PAMPs and alarmins: All we need to know about danger. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2007, 81, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Land, W.G. Transfusion-Related Acute Lung Injury: The Work of DAMPs. Transfus. Med. Hemother. 2013, 40, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Wang, H.; Ding, A.; Golenbock, D.T.; Latz, E.; Czura, C.J.; Fenton, M.J.; Tracey, K.J.; Yang, H. HMGB1 signals through toll-like receptor (TLR) 4 and TLR2. Shock 2006, 26, 174–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Kang, R.; Tang, D. The mechanism of HMGB1 secretion and release. Exp. Mol. Med. 2022, 54, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silk, E.; Zhao, H.; Weng, H.; Ma, D. The role of extracellular histone in organ injury. Cell Death Dis. 2017, 8, e2812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apel, F.; Andreeva, L.; Knackstedt, L.S.; Streeck, R.; Frese, C.K.; Goosmann, C.; Hopfner, K.P.; Zychlinsky, A. The cytosolic DNA sensor cGAS recognizes neutrophil extracellular traps. Sci. Signal 2021, 14, eaax7942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisetsky, D.S. The origin and properties of extracellular DNA: From PAMP to DAMP. Clin. Immunol. 2012, 144, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandler, N.; Kaczmarek, E.; Itagaki, K.; Zheng, Y.; Otterbein, L.; Khabbaz, K.; Liu, D.; Senthilnathan, V.; Gruen, R.L.; Hauser, C.J. Mitochondrial DAMPs Are Released During Cardiopulmonary Bypass Surgery and Are Associated with Postoperative Atrial Fibrillation. Heart Lung Circ. 2018, 27, 122–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amores-Iniesta, J.; Barberà-Cremades, M.; Martínez, C.M.; Pons, J.A.; Revilla-Nuin, B.; Martínez-Alarcón, L.; Di Virgilio, F.; Parrilla, P.; Baroja-Mazo, A.; Pelegrín, P. Extracellular ATP Activates the NLRP3 Inflammasome and Is an Early Danger Signal of Skin Allograft Rejection. Cell Rep. 2017, 21, 3414–3426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorward, D.A.; Lucas, C.D.; Chapman, G.B.; Haslett, C.; Dhaliwal, K.; Rossi, A.G. The role of formylated peptides and formyl peptide receptor 1 in governing neutrophil function during acute inflammation. Am. J. Pathol. 2015, 185, 1172–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Sun, P.; Zhang, J.C.; Zhang, Q.; Yao, S.L. Proinflammatory effects of S100A8/A9 via TLR4 and RAGE signaling pathways in BV-2 microglial cells. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2017, 40, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braga, T.T.; Forni, M.F.; Correa-Costa, M.; Ramos, R.N.; Barbuto, J.A.; Branco, P.; Castoldi, A.; Hiyane, M.I.; Davanso, M.R.; Latz, E.; et al. Soluble Uric Acid Activates the NLRP3 Inflammasome. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 39884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roedig, H.; Nastase, M.V.; Frey, H.; Moreth, K.; Zeng-Brouwers, J.; Poluzzi, C.; Hsieh, L.T.; Brandts, C.; Fulda, S.; Wygrecka, M.; et al. Biglycan is a new high-affinity ligand for CD14 in macrophages. Matrix Biol. 2019, 77, 4–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oshima, K.; Haeger, S.M.; Hippensteel, J.A.; Herson, P.S.; Schmidt, E.P. More than a biomarker: The systemic consequences of heparan sulfate fragments released during endothelial surface layer degradation (2017 Grover Conference Series). Pulm. Circ. 2018, 8, 2045893217745786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takeuchi, O.; Akira, S. Pattern recognition receptors and inflammation. Cell 2010, 140, 805–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, D.; Kang, R.; Berghe, T.V.; Vandenabeele, P.; Kroemer, G. The molecular machinery of regulated cell death. Cell Res. 2019, 29, 347–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murao, A.; Aziz, M.; Wang, H.; Brenner, M.; Wang, P. Release mechanisms of major DAMPs. Apoptosis 2021, 26, 152–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eefting, F.; Rensing, B.; Wigman, J.; Pannekoek, W.J.; Liu, W.M.; Cramer, M.J.; Lips, D.J.; Doevendans, P.A. Role of apoptosis in reperfusion injury. Cardiovasc. Res. 2004, 61, 414–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bell, C.W.; Jiang, W.; Reich, C.F., III; Pisetsky, D.S. The extracellular release of HMGB1 during apoptotic cell death. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2006, 291, C1318–C1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delogu, G.; Moretti, S.; Antonucci, A.; Marcellini, S.; Masciangelo, R.; Famularo, G.; Signore, L.; De Simone, C. Apoptosis and surgical trauma: Dysregulated expression of death and survival factors on peripheral lymphocytes. Arch. Surg. 2000, 135, 1141–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denton, D.; Kumar, S. Autophagy-dependent cell death. Cell Death Differ. 2019, 26, 605–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, P.; Zhang, X.; Liu, N.; Tang, L.; Peng, C.; Chen, X. Pyroptosis: Mechanisms and diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021, 6, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaczmarek, A.; Vandenabeele, P.; Krysko, D.V. Necroptosis: The release of damage-associated molecular patterns and its physiological relevance. Immunity 2013, 38, 209–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davaanyam, D.; Lee, H.; Seol, S.I.; Oh, S.A.; Kim, S.W.; Lee, J.K. HMGB1 induces hepcidin upregulation in astrocytes and causes an acute iron surge and subsequent ferroptosis in the postischemic brain. Exp. Mol. Med. 2023, 55, 2402–2416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maisat, W.; Hou, L.; Sandhu, S.; Sin, Y.C.; Kim, S.; Van Pelt, H.; Chen, Y.; Emani, S.; Kong, S.W.; Emani, S.; et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps formation is associated with postoperative complications in congenital cardiac surgery. Pediatr. Res. 2024, 98, 1545–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caudrillier, A.; Kessenbrock, K.; Gilliss, B.M.; Nguyen, J.X.; Marques, M.B.; Monestier, M.; Toy, P.; Werb, Z.; Looney, M.R. Platelets induce neutrophil extracellular traps in transfusion-related acute lung injury. J. Clin. Investig. 2012, 122, 2661–2671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colicchia, M.; Perrella, G.; Gant, P.; Rayes, J. Novel mechanisms of thrombo-inflammation during infection: Spotlight on neutrophil extracellular trap-mediated platelet activation. Res. Pract. Thromb. Haemost. 2023, 7, 100116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salvadori, M.; Rosso, G.; Bertoni, E. Update on ischemia-reperfusion injury in kidney transplantation: Pathogenesis and treatment. World J. Transpl. 2015, 5, 52–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasorsa, F.; Rutigliano, M.; Milella, M.; d’Amati, A.; Crocetto, F.; Pandolfo, S.D.; Barone, B.; Ferro, M.; Spilotros, M.; Battaglia, M.; et al. Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury in Kidney Transplantation: Mechanisms and Potential Therapeutic Targets. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 4332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvis, M.J.M.; Kaffka Genaamd Dengler, S.E.; Odille, C.A.; Mishra, M.; van der Kaaij, N.P.; Doevendans, P.A.; Sluijter, J.P.G.; de Kleijn, D.P.V.; de Jager, S.C.A.; Bosch, L.; et al. Damage-Associated Molecular Patterns in Myocardial Infarction and Heart Transplantation: The Road to Translational Success. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 599511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Squiccimarro, E.; Stasi, A.; Lorusso, R.; Paparella, D. Narrative review of the systemic inflammatory reaction to cardiac surgery and cardiopulmonary bypass. Artif. Organs 2022, 46, 568–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dybdahl, B.; Wahba, A.; Lien, E.; Flo, T.H.; Waage, A.; Qureshi, N.; Sellevold, O.F.; Espevik, T.; Sundan, A. Inflammatory response after open heart surgery: Release of heat-shock protein 70 and signaling through toll-like receptor-4. Circulation 2002, 105, 685–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim-Shapiro, D.B.; Lee, J.; Gladwin, M.T. Storage lesion: Role of red blood cell breakdown. Transfusion 2011, 51, 844–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, T.; Prudent, M.; D’Alessandro, A. Red blood cell storage lesion: Causes and potential clinical consequences. Blood Transfus. 2019, 17, 27–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peltz, E.D.; Moore, E.E.; Eckels, P.C.; Damle, S.S.; Tsuruta, Y.; Johnson, J.L.; Sauaia, A.; Silliman, C.C.; Banerjee, A.; Abraham, E. HMGB1 is markedly elevated within 6 hours of mechanical trauma in humans. Shock 2009, 32, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neal, M.D.; Raval, J.S.; Triulzi, D.J.; Simmons, R.L. Innate immune activation after transfusion of stored red blood cells. Transfus. Med. Rev. 2013, 27, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, W.; Sun, Z.; He, S.; Zhang, W.; Chen, S.; Cao, Y.N.; Wang, N. Mechanical ventilation induces lung and brain injury through ATP production, P2Y1 receptor activation and dopamine release. Bioengineered 2022, 13, 2346–2359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plötz, F.B.; Slutsky, A.S.; van Vught, A.J.; Heijnen, C.J. Ventilator-induced lung injury and multiple system organ failure: A critical review of facts and hypotheses. Intensive Care Med. 2004, 30, 1865–1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuipers, M.T.; van der Poll, T.; Schultz, M.J.; Wieland, C.W. Bench-to-bedside review: Damage-associated molecular patterns in the onset of ventilator-induced lung injury. Crit. Care 2011, 15, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao, Y.; Saredy, J.; Yang, W.Y.; Sun, Y.; Lu, Y.; Saaoud, F.; Drummer, C.T.; Johnson, C.; Xu, K.; Jiang, X.; et al. Vascular Endothelial Cells and Innate Immunity. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2020, 40, e138–e152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Sursal, T.; Adibnia, Y.; Zhao, C.; Zheng, Y.; Li, H.; Otterbein, L.E.; Hauser, C.J.; Itagaki, K. Mitochondrial DAMPs increase endothelial permeability through neutrophil dependent and independent pathways. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e59989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, V.; Kaur, R.; Kumari, P.; Pasricha, C.; Singh, R. ICAM-1 and VCAM-1: Gatekeepers in various inflammatory and cardiovascular disorders. Clin. Chim. Acta 2023, 548, 117487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riedel, B.; Schier, R. Endothelial dysfunction in the perioperative setting. Semin. Cardiothorac. Vasc. Anesth. 2010, 14, 41–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, I.; Panicker, S.R.; Cai, X.; Mehta-D’souza, P.; Rezaie, A.R. Inorganic Polyphosphate Amplifies High Mobility Group Box 1-Mediated Von Willebrand Factor Release and Platelet String Formation on Endothelial Cells. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2018, 38, 1868–1877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, T.; Kawahara, K.; Nakamura, T.; Yamada, S.; Nakamura, T.; Abeyama, K.; Hashiguchi, T.; Maruyama, I. High-mobility group box 1 protein promotes development of microvascular thrombosis in rats. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2007, 5, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhagirath, V.C.; Dwivedi, D.J.; Liaw, P.C. Comparison of the Proinflammatory and Procoagulant Properties of Nuclear, Mitochondrial, and Bacterial DNA. Shock 2015, 44, 265–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Fang, C.; Gao, H.; Bilodeau, M.L.; Zhang, Z.; Croce, K.; Liu, S.; Morooka, T.; Sakuma, M.; Nakajima, K.; et al. Platelet-derived S100 family member myeloid-related protein-14 regulates thrombosis. J. Clin. Investig. 2014, 124, 2160–2171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimono, K.; Ito, T.; Kamikokuryo, C.; Niiyama, S.; Yamada, S.; Onishi, H.; Yoshihara, H.; Maruyama, I.; Kakihana, Y. Damage-associated molecular patterns and fibrinolysis perturbation are associated with lethal outcomes in traumatic injury. Thromb. J. 2023, 21, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gould, T.J.; Vu, T.T.; Stafford, A.R.; Dwivedi, D.J.; Kim, P.Y.; Fox-Robichaud, A.E.; Weitz, J.I.; Liaw, P.C. Cell-Free DNA Modulates Clot Structure and Impairs Fibrinolysis in Sepsis. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2015, 35, 2544–2553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahbar, E.; Cardenas, J.C.; Baimukanova, G.; Usadi, B.; Bruhn, R.; Pati, S.; Ostrowski, S.R.; Johansson, P.I.; Holcomb, J.B.; Wade, C.E. Endothelial glycocalyx shedding and vascular permeability in severely injured trauma patients. J. Transl. Med. 2015, 13, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ito, T.; Totoki, T.; Yokoyama, Y.; Yasuda, T.; Furubeppu, H.; Yamada, S.; Maruyama, I.; Kakihana, Y. Serum histone H3 levels and platelet counts are potential markers for coagulopathy with high risk of death in septic patients: A single-center observational study. J. Intensive Care 2019, 7, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mao, J.Y.; Li, D.K.; Zhang, H.M.; Wang, X.T.; Liu, D.W. Plasma mitochondrial DNA levels are associated with acute lung injury and mortality in septic patients. BMC Pulm. Med. 2021, 21, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Liang, F.; Ye, M.; Wu, S.; Qin, Y.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, L.; He, J.; Cen, L.; Lin, F. GSDMD promotes neutrophil extracellular traps via mtDNA-cGAS-STING pathway during lung ischemia/reperfusion. Cell Death Discov. 2023, 9, 368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, W.; Peng, F.; Lou, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhao, N.; Shao, Q.; Chen, J.; Qian, K.; Zeng, Z.; Zhan, Y.; et al. Autophagy alleviates mitochondrial DAMP-induced acute lung injury by inhibiting NLRP3 inflammasome. Life Sci. 2021, 265, 118833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Raoof, M.; Chen, Y.; Sumi, Y.; Sursal, T.; Junger, W.; Brohi, K.; Itagaki, K.; Hauser, C.J. Circulating mitochondrial DAMPs cause inflammatory responses to injury. Nature 2010, 464, 104–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Zoelen, M.A.; Ishizaka, A.; Wolthuls, E.K.; Choi, G.; van der Poll, T.; Schultz, M.J. Pulmonary levels of high-mobility group box 1 during mechanical ventilation and ventilator-associated pneumonia. Shock 2008, 29, 441–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, L.; Yang, Z.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, Y.; Yang, H.; Zheng, B.; Tian, W.; Wang, S.; He, Z.; et al. NLRP3/ASC-mediated alveolar macrophage pyroptosis enhances HMGB1 secretion in acute lung injury induced by cardiopulmonary bypass. Lab. Investig. 2018, 98, 1052–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, Y.; Hou, L.; Xu, Q.; Liu, Q.; Pan, S.; Gao, Y.; Dixon, R.A.F.; He, Z.; Wang, X. Cardiopulmonary Bypass Induces Acute Lung Injury via the High-Mobility Group Box 1/Toll-Like Receptor 4 Pathway. Dis. Markers 2020, 2020, 8854700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, Y.; Ling, Y.; Deng, Q.; Qiu, Y.; Shen, J.; Lai, H.; Chen, Z.; Huang, C.; Liang, L.; Li, X.; et al. HMGB1-Mediated Neutrophil Extracellular Trap Formation Exacerbates Intestinal Ischemia/Reperfusion-Induced Acute Lung Injury. J. Immunol. 2022, 208, 968–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Guan, L.; Yu, J.; Zhao, Z.; Mao, L.; Li, S.; Zhao, J. Pulmonary endothelial activation caused by extracellular histones contributes to neutrophil activation in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Respir. Res. 2016, 17, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Fu, Y.; Gao, J.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, N.; Zhang, Z.; Jiang, X.; Chen, C.; Wen, Z. Cathepsin C from extracellular histone-induced M1 alveolar macrophages promotes NETosis during lung ischemia-reperfusion injury. Redox Biol. 2024, 74, 103231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittkowski, H.; Sturrock, A.; van Zoelen, M.A.; Viemann, D.; van der Poll, T.; Hoidal, J.R.; Roth, J.; Foell, D. Neutrophil-derived S100A12 in acute lung injury and respiratory distress syndrome. Crit. Care Med. 2007, 35, 1369–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Lu, R.; Chen, J.; Xie, M.; Zhao, X.; Kong, L. S100A9 blockade prevents lipopolysaccharide-induced lung injury via suppressing the NLRP3 pathway. Respir. Res. 2021, 22, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhamdi, Y.; Abrams, S.T.; Cheng, Z.; Jing, S.; Su, D.; Liu, Z.; Lane, S.; Welters, I.; Wang, G.; Toh, C.H. Circulating Histones Are Major Mediators of Cardiac Injury in Patients with Sepsis. Crit. Care Med. 2015, 43, 2094–2103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, M.; He, Z.; Rauf, A.; Beikoghli Kalkhoran, S.; Heiestad, C.M.; Stensløkken, K.O.; Parish, C.R.; Soehnlein, O.; Arjun, S.; Davidson, S.M.; et al. Extracellular histones are a target in myocardial ischaemia-reperfusion injury. Cardiovasc. Res. 2022, 118, 1115–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Duan, J.; Zhou, Y.; Cao, M.; Su, Y.; Jiang, D.; Tao, A.; Yuan, W.; Dai, Z. Endothelial HMGB1-AIM2 axis worsens myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury by regulating endothelial pyroptosis. Apoptosis 2025, 30, 2466–2479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrassy, M.; Volz, H.C.; Igwe, J.C.; Funke, B.; Eichberger, S.N.; Kaya, Z.; Buss, S.; Autschbach, F.; Pleger, S.T.; Lukic, I.K.; et al. High-mobility group box-1 in ischemia-reperfusion injury of the heart. Circulation 2008, 117, 3216–3226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.S.; Yang, J.; Chen, P.; Yang, J.; Bo, S.Q.; Ding, J.W.; Yu, Q.Q. The HMGB1-TLR4 axis contributes to myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury via regulation of cardiomyocyte apoptosis. Gene 2013, 527, 389–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Chen, B.; Yang, X.; Zhang, C.; Jiao, Y.; Li, P.; Liu, Y.; Li, Z.; Qiao, B.; Bond Lau, W.; et al. S100a8/a9 Signaling Causes Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Cardiomyocyte Death in Response to Ischemic/Reperfusion Injury. Circulation 2019, 140, 751–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manghelli, J.L.; Kelly, M.O.; Carter, D.I.; Gauthier, J.M.; Scozzi, D.; Lancaster, T.S.; MacGregor, R.M.; Khiabani, A.J.; Schuessler, R.B.; Gelman, A.E.; et al. Pericardial Mitochondrial DNA Levels Are Associated with Atrial Fibrillation After Cardiac Surgery. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2021, 111, 1593–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qu, C.; Wang, X.W.; Huang, C.; Qiu, F.; Xiang, X.Y.; Lu, Z.Q. High mobility group box 1 gene polymorphism is associated with the risk of postoperative atrial fibrillation after coronary artery bypass surgery. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2015, 10, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Ma, J.; Wang, P.; Corpuz, T.M.; Panchapakesan, U.; Wyburn, K.R.; Chadban, S.J. HMGB1 contributes to kidney ischemia reperfusion injury. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2010, 21, 1878–1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, A.; Wang, S.; Liu, W.; Haig, A.; Zhang, Z.X.; Jevnikar, A.M. Glycyrrhizic acid ameliorates HMGB1-mediated cell death and inflammation after renal ischemia reperfusion injury. Am. J. Nephrol. 2014, 40, 84–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Ren, J.; Wu, J.; Li, G.; Wu, X.; Liu, S.; Wang, G.; Gu, G.; Ren, H.; Hong, Z.; et al. Urinary Mitochondrial DNA Levels Identify Acute Kidney Injury in Surgical Critical Illness Patients. Shock 2017, 48, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitaker, R.M.; Stallons, L.J.; Kneff, J.E.; Alge, J.L.; Harmon, J.L.; Rahn, J.J.; Arthur, J.M.; Beeson, C.C.; Chan, S.L.; Schnellmann, R.G. Urinary mitochondrial DNA is a biomarker of mitochondrial disruption and renal dysfunction in acute kidney injury. Kidney Int. 2015, 88, 1336–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakazawa, D.; Kumar, S.V.; Marschner, J.; Desai, J.; Holderied, A.; Rath, L.; Kraft, F.; Lei, Y.; Fukasawa, Y.; Moeckel, G.W.; et al. Histones and Neutrophil Extracellular Traps Enhance Tubular Necrosis and Remote Organ Injury in Ischemic AKI. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2017, 28, 1753–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsung, A.; Sahai, R.; Tanaka, H.; Nakao, A.; Fink, M.P.; Lotze, M.T.; Yang, H.; Li, J.; Tracey, K.J.; Geller, D.A.; et al. The nuclear factor HMGB1 mediates hepatic injury after murine liver ischemia-reperfusion. J. Exp. Med. 2005, 201, 1135–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuchs, T.A.; Bhandari, A.A.; Wagner, D.D. Histones induce rapid and profound thrombocytopenia in mice. Blood 2011, 118, 3708–3714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakahara, M.; Ito, T.; Kawahara, K.; Yamamoto, M.; Nagasato, T.; Shrestha, B.; Yamada, S.; Miyauchi, T.; Higuchi, K.; Takenaka, T.; et al. Recombinant thrombomodulin protects mice against histone-induced lethal thromboembolism. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e75961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatada, T.; Wada, H.; Nobori, T.; Okabayashi, K.; Maruyama, K.; Abe, Y.; Uemoto, S.; Yamada, S.; Maruyama, I. Plasma concentrations and importance of High Mobility Group Box protein in the prognosis of organ failure in patients with disseminated intravascular coagulation. Thromb. Haemost. 2005, 94, 975–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, G.X.; Wang, T.; Chen, M.H.; Hu, Z.H.; Ouyang, W. Serum high-mobility group box 1 protein correlates with cognitive decline after gastrointestinal surgery. Acta Anaesthesiol. Scand. 2014, 58, 668–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.J.; Wang, Y.; Le, Y.; Duan, K.M.; Yan, X.B.; Liao, Q.; Liao, Y.; Tong, J.B.; Terrando, N.; Ouyang, W. Surgery upregulates high mobility group box-1 and disrupts the blood-brain barrier causing cognitive dysfunction in aged rats. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2012, 18, 994–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, R.L.; Zhang, Z.Z.; Peng, M.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, J.J.; Wang, C.Y.; Wang, Y.L. Postoperative impairment of cognitive function in old mice: A possible role for neuroinflammation mediated by HMGB1, S100B, and RAGE. J. Surg. Res. 2013, 185, 815–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, N.S.; Zhong, W.J.; Sha, H.X.; Zhang, C.Y.; Jin, L.; Duan, J.X.; Xiong, J.B.; You, Z.J.; Zhou, Y.; Guan, C.X. mtDNA-cGAS-STING axis-dependent NLRP3 inflammasome activation contributes to postoperative cognitive dysfunction induced by sevoflurane in mice. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2024, 20, 1927–1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.M.; Yu, C.J.; Liu, Y.H.; Dong, H.Q.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, S.S.; Hu, L.Q.; Zhang, F.; Qian, Y.N.; Gui, B. S100A8 contributes to postoperative cognitive dysfunction in mice undergoing tibial fracture surgery by activating the TLR4/MyD88 pathway. Brain Behav. Immun. 2015, 44, 221–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, T.; Si, Y. PCSK9 exacerbates sevoflurane-induced neuroinflammatory response and apoptosis by up-regulating cGAS-STING signal. Tissue Cell 2025, 93, 102739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joe, Y.E.; Jun, J.H.; Oh, J.E.; Lee, J.R. Damage-associated molecular patterns as a mechanism of sevoflurane-induced neuroinflammation in neonatal rodents. Korean J. Anesth. 2024, 77, 468–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, Y.; Liu, P.; Zhou, Y.; Ding, X.; Liu, H.; Yang, J. Prenatal Sevoflurane Exposure Impairs the Learning and Memory of Rat Offspring via HMGB1-Induced NLRP3/ASC Inflammasome Activation. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2023, 14, 699–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, L.; Ge, F.; Hu, Y.; Yu, Y.; Guo, K.; Miao, C. Sevoflurane Postconditioning Attenuates Hepatic Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury by Limiting HMGB1/TLR4/NF-κB Pathway via Modulating microRNA-142 in vivo and in vitro. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 646307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Li, Y.; Chi, F.; Ma, L.; Li, Y.; Hou, Z.; Wang, Q. Sevoflurane postconditioning ameliorates cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury in rats via TLR4/MyD88/TRAF6 signaling pathway. Aging 2022, 14, 10153–10170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, Y.; Xie, K.; Zhou, Q.; He, R.; Chen, Z.; Feng, W. Sevoflurane alleviates myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury via actitation of heat shock protein-70 in patients undergoing double valve replacement surgery. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2022, 14, 5529–5540. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, T.; Huang, Z. Effects of Isoflurane on the Cell Pyroptosis in the Lung Cancer Through the HMGB1/RAGE Pathway. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2024, 196, 3786–3799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, D.; Zhou, Z.; Liu, J.; Wang, T.; Yin, J. Neuroprotective effects of isoflurane against lipopolysaccharide-induced neuroinflammation in BV2 microglial cells by regulating HMGB1/TLRs pathway. Folia Neuropathol. 2020, 58, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.; Deng, B.; Zhao, X.; Gao, C.; Yang, L.; Zhao, H.; Yu, D.; Zhang, F.; Xu, L.; Chen, L.; et al. Isoflurane preconditioning provides neuroprotection against stroke by regulating the expression of the TLR4 signalling pathway to alleviate microglial activation. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 11445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bian, W.Y.; Chen, Y.P.; Xu, B.; Tang, J. Pretreatment with Propofol Reduces Pulmonary Injury in a Pig Model of Intestinal Ischemia-Reperfusion via Suppressing the High-Mobility Group Box 1 Protein (HMGB1)/Toll-Like Receptor 4 (TLR4)/Protein Kinase R (PKR) Signaling Pathway. Med. Sci. Monit. 2021, 27, e930478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z.; Wang, J.W.; Wang, Y.; Dong, W.W.; Xu, Z.F. Propofol Protects Lung Endothelial Barrier Function by Suppression of High-Mobility Group Box 1 (HMGB1) Release and Mitochondrial Oxidative Damage Catalyzed by HMGB1. Med. Sci. Monit. 2019, 25, 3199–3211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, H.; Gu, Y.; Chen, H. Propofol ameliorates endotoxin-induced myocardial cell injury by inhibiting inflammation and apoptosis via the PPARγ/HMGB1/NLRP3 axis. Mol. Med. Rep. 2021, 23, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.M.; Sun, J.G.; Hu, L.H.; Ma, X.C.; Zhou, G.; Huang, X.Z. Propofol-mediated cardioprotection dependent of microRNA-451/HMGB1 against myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury. J. Cell Physiol. 2019, 234, 23289–23301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, M.; Zhao, L.; Wang, Y.; Guo, Q.; An, Q.; Geng, J.; Zhang, C.; Guo, Z. Ketamine Regulates the Autophagy Flux and Polarization of Microglia through the HMGB1-RAGE Axis and Exerts Antidepressant Effects in Mice. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2022, 81, 931–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Sun, X.; Zhang, Y.; Cao, L. Ketamine alleviates HMGB1-induced acute lung injury through TLR4 signaling pathway. Adv. Clin. Exp. Med. 2020, 29, 813–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Wang, C.Y.; Shen, A. Ketamine alleviates LPS induced lung injury by inhibiting HMGB1-RAGE level. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2018, 22, 1830–1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Yang, J.; Han, X. Ketamine attenuates sepsis-induced acute lung injury via regulation of HMGB1-RAGE pathways. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2016, 34, 114–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Wang, Z.; Han, G.; Huang, L.; Jiang, J.; Li, S. Ketamine attenuates high mobility group box-1-induced inflammatory responses in endothelial cells. J. Surg. Res. 2016, 200, 593–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Liang, S.; Li, C.; Li, B.; He, M.; Li, K.; Fu, W.; Li, S.; Mi, H. Mitochondrial damage causes inflammation via cGAS-STING signaling in ketamine-induced cystitis. Inflamm. Res. 2025, 74, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Xin, Y.; Chu, T.; Liu, C.; Xu, A. Dexmedetomidine attenuates perioperative neurocognitive disorders by suppressing hippocampal neuroinflammation and HMGB1/RAGE/NF-κB signaling pathway. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 150, 113006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, W.; Zhou, R.; Qu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Song, N.; Liang, R.; Qian, J. Dexmedetomidine preconditioning mitigates myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury via inhibition of mast cell degranulation. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 141, 111853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Zhang, J.; Ainiwaer, Y.; He, B.; Geng, Q.; Lin, L.; Li, X. Dexmedetomidine Attenuates Myocardial Injury Induced by Renal Ischemia/Reperfusion by Inhibiting the HMGB1-TLR4-MyD88-NF-κB Signaling Pathway. Ann. Clin. Lab. Sci. 2021, 51, 376–384. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, S.; Wang, Q.; Gao, H.; Zhao, X.; Zhi, J.; Yang, D. Dexmedetomidine alleviates airway hyperresponsiveness and allergic airway inflammation through the TLR4/NF-κB signaling pathway in mice. Mol. Med. Rep. 2022, 25, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Hu, H.; Xu, X.; Fang, M.; Tao, T.; Liang, Z. Protective effect of dexmedetomidine in cecal ligation perforation-induced acute lung injury through HMGB1/RAGE pathway regulation and pyroptosis activation. Bioengineered 2021, 12, 10608–10623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Huang, Y.; Xiong, B.; Luo, H.; Song, X. Dexmedetomidine ameliorates renal ischemia reperfusion-mediated activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome in alveolar macrophages. Gene 2020, 758, 144973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Jiang, Z.; Zhou, X.; Sun, X.; Cao, J.; Liu, Y.; Wang, X. Dexmedetomidine Preconditioning Protects Cardiomyocytes Against Hypoxia/Reoxygenation-Induced Necroptosis by Inhibiting HMGB1-Mediated Inflammation. Cardiovasc. Drugs Ther. 2019, 33, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, W.; He, Y.; Lin, D.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, N.; Xie, T.; Wei, H. Dexmedetomidine mitigates lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury by modulating heat shock protein A12B to inhibit the toll-like receptor 4/nuclear factor-kappa B signaling pathway. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2024, 398, 111112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, S.H.; Jue, M.J.; Kim, Y.H.; Cho, S.; Kim, W.J.; Kim, K.M.; Han, J.I.; Lee, H. The Effect of Dexmedetomidine on the Mini-Cog Score and High-Mobility Group Box 1 Levels in Elderly Patients with Postoperative Neurocognitive Disorders Undergoing Orthopedic Surgery. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 6610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Q.; Liang, B.; Leng, Z.; Ma, W.; Chen, Y.; Xie, Y. Remimazolam ameliorates postoperative cognitive dysfunction after deep hypothermic circulatory arrest through HMGB1-TLR4-NF-κB pathway. Brain Res. Bull. 2024, 217, 111086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, K.H.; Choi, J.W.; Jung, H.S.; Yoo, H.; Joo, J.D. The Effects of Remifentanil on Expression of High Mobility Group Box 1 in Septic Rats. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2017, 32, 542–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Yin, Y. Dual roles of anesthetics in postoperative cognitive dysfunction: Regulation of microglial activation through inflammatory signaling pathways. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1102312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behnaz, F.; Erfanian, M.; Chegini, A. Comparison of the Effects of Isoflurane and Propofol as Anesthesia Maintenance on Plasma Mitochondrial DNA Levels in Posterior Spinal Fusion Surgeries. Anesth. Pain Med. 2025, 15, e161767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weng, Y.; Yuan, S.; Li, H.; Yu, W. Comparison of Cardioprotective Effects of Propofol versus Sevoflurane in Pediatric Living Donor Liver Transplantation. Ann. Transpl. 2020, 25, e923398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graf, H.; Gräfe, C.; Bruegel, M.; Happich, F.L.; Wustrow, V.; Wegener, A.; Wilfert, W.; Zoller, M.; Liebchen, U.; Paal, M.; et al. Extracorporeal Elimination of Pro- and Anti-inflammatory Modulators by the Cytokine Adsorber CytoSorb® in Patients with Hyperinflammation: A Prospective Study. Infect. Dis. Ther. 2024, 13, 2089–2101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hyslop, K.; Ki, K.K.; Naidoo, R.; O’Brien, D.; Prabhu, A.; Gill, D.; Anstey, C.; Rapchuk, I.L.; McDonald, C.I.; Marshall, L.; et al. Cell-free mitochondrial DNA may predict the risk of post-operative complications and outcomes in surgical aortic valve replacement patients. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 15857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pencovich, N.; Nevo, N.; Weiser, R.; Bonder, E.; Bogoch, Y.; Nachmany, I. Postoperative Rise of Circulating Mitochondrial DNA Is Associated with Inflammatory Response in Patients following Pancreaticoduodenectomy. Eur. Surg. Res. 2021, 62, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Location /Source | Acronym | Full Name | Function (Normal) | PRRs/Recognition Pathways | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nuclear | HMGB1 | High-Mobility Group Box 1 | Chromatin binding; transcriptional regulation | TLR2, TLR4, RAGE | [12,13] |

| Histones | Histone proteins | Structural organization and stability of chromatin | TLR2, TLR4, TLR9; direct endothelial binding | [14] | |

| Extracellular DNA | Nuclear DNA (cfDNA) | Genetic material | TLR9, cGAS–STING | [15,16] | |

| Mitochondrial | mtDNA | Mitochondrial DNA | Encodes mitochondrial proteins | TLR9, cGAS–STING, NLRP3 | [17] |

| ATP | Adenosine triphosphate | Energy currency of the cell | P2X7; NLRP3 inflammasome | [18] | |

| N-formyl peptides | Mitochondrial peptides | Chemotactic signals | FPR-1 | [19] | |

| Cytosolic | S100A8/A9 | S100 calcium-binding proteins A8/A9 | Stress response; intracellular signaling | RAGE, TLR4 | [20] |

| S100A12 | S100 calcium-binding protein A12 | Proinflammatory mediator | RAGE, TLR4 | [10] | |

| HSPs | Heat-shock proteins | Molecular chaperones; protein folding | TLR2, TLR4 | [10] | |

| UA | Uric acid | End product of purine metabolism | NLRP3 inflammasome | [21] | |

| Extracellular matrix (ECM) | Biglycan | Small leucine-rich proteoglycan | Structural support; released upon ECM damage | TLR2, TLR4 | [22] |

| LMW-HA | Low molecular weight hyaluronan | ECM degradation fragment | TLR2, TLR4 | [22] | |

| Heparan sulfate | Glycosaminoglycan fragments | ECM component; endothelial injury signal | TLR4 | [23] | |

| Blood/Transfusion-related | Free heme | Cell-free heme | Oxygen transport; pro-oxidant when released | TLR4 | [11] |

| Lipid peroxidation products | n/a | n/a | TLR4 | [11] | |

| Microparticles | Platelet- or FFP- or RBC-derived vesicles | n/a | NLRP3 | [11] |

| Clinical Manifestation | DAMPs Involved | Triggers | Mechanisms/Pathways | Clinical/Experimental Relevance | Evidence Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALI/ARDS | mtDNA |

|

|

| Clinical observation [61] |

|

|

| Preclinical (mice) [62] | ||

| MTD |

|

|

| Preclinical (mice) [63,64] | |

| HGMB1 |

|

|

| Clinical RCT [65] | |

|

|

| Preclinical (rat) [66,67] | ||

|

|

| Preclinical (mice) [68] | ||

| Histones |

|

|

| Preclinical (mice) [69] | |

|

|

| Clinical case–control; preclinical (mice) [70] | ||

| S100A12 |

|

|

| Clinical case–control; experimental [71] | |

| S100A9 |

|

|

| Preclinical (mice) [72] | |

| Extracellular ATP |

|

|

| Preclinical (mice) [46] | |

| Myocardial dysfunction | Histones |

|

|

| Clinical case–control; preclinical (mice) [73] |

|

|

| Preclinical (rat) [74] | ||

| HMGB1 |

|

|

| Preclinical (murine) [75] | |

|

|

| Preclinical (mice) [76] | ||

|

|

| Preclinical (mice) [77] | ||

| S100A8/A9 |

|

|

| Clinical observation; preclinical (mice) [78] | |

| POAF | mtDNA |

|

|

| Clinical observation [17,79] |

| HMGB1 |

|

|

| Clinical observation [80] | |

| AKI | HGMB1 |

|

|

| Preclinical (mice) [81] |

|

|

| Experimental; preclinical (mice) [82] | ||

| mtDNA |

|

|

| Clinical observation [83] | |

|

|

| Clinical observation [84] | ||

| Histone |

|

|

| Clinical observation; preclinical (mice); experimental [85] | |

| Liver | HMGB1 |

|

|

| Experimental; preclinical [86] |

| Coagulopathy | Histone |

|

|

| Clinical observation [60] |

| Heparan sulfate |

|

|

| Clinical observation [59] | |

| DIC | Histone |

|

|

| Preclinical (mice) [87] |

| Histone |

|

|

| Clinical case–control; preclinical [34,88] | |

| HMBG1 |

|

|

| Clinical observation [89] | |

| PND (POD/POCD) | HMGB1 |

|

|

| Clinical [90] |

|

|

| Preclinical (rat, mice) [91,92] | ||

| mtDNA |

|

|

| Preclinical (mice) [93] | |

| S100A8/A9 |

|

|

| Preclinical (mice) [94] |

| Agent | DAMPs Affected | Pathways/Mechanisms | Reported Effects (Preclinical Study) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Volatile agents | |||

| Sevoflurane |

| ||

| Isoflurane |

|

| |

| Intravenous agents | |||

| Propofol | |||

| Ketamine |

|

| |

| Adjuncts | |||

| Dexmedetomidine (DEX) |

|

| |

| Remimazolam |

|

|

|

| Opioids | |||

| Remifentanil |

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Maisat, W.; Yuki, K. Damage-Associated Molecular Patterns in Perioperative Anesthesia Care: A Clinical Perspective. Anesth. Res. 2026, 3, 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/anesthres3010001

Maisat W, Yuki K. Damage-Associated Molecular Patterns in Perioperative Anesthesia Care: A Clinical Perspective. Anesthesia Research. 2026; 3(1):1. https://doi.org/10.3390/anesthres3010001

Chicago/Turabian StyleMaisat, Wiriya, and Koichi Yuki. 2026. "Damage-Associated Molecular Patterns in Perioperative Anesthesia Care: A Clinical Perspective" Anesthesia Research 3, no. 1: 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/anesthres3010001

APA StyleMaisat, W., & Yuki, K. (2026). Damage-Associated Molecular Patterns in Perioperative Anesthesia Care: A Clinical Perspective. Anesthesia Research, 3(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/anesthres3010001