The Role of Sensory Cues in Promoting Healthy Eating: A Narrative Synthesis and Gastronomic Implications

Abstract

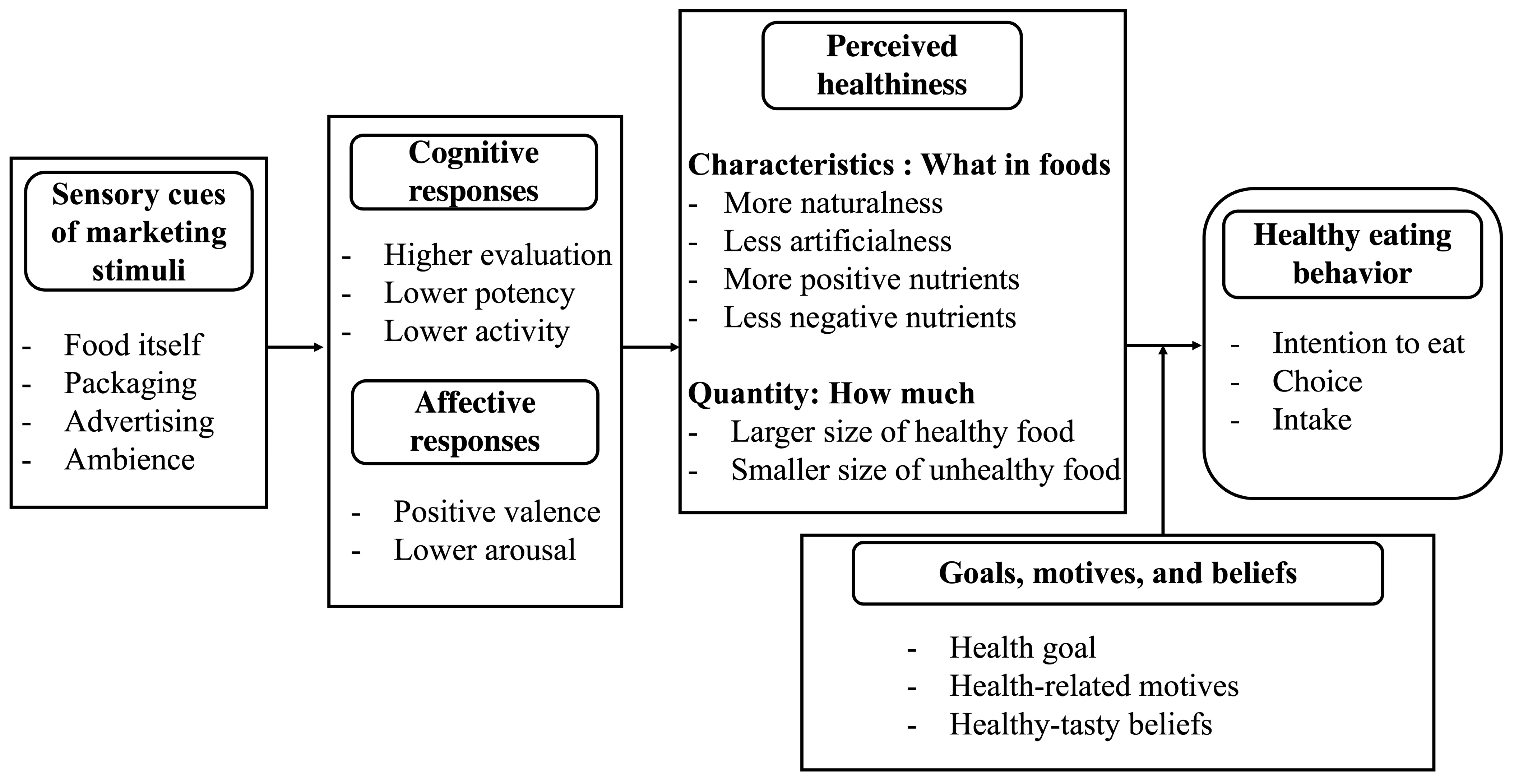

1. Introduction

2. Cognitive Responses to Sensory Factors Influencing Healthy Eating Behavior

2.1. The Framework of Meanings of Concepts

2.2. The Connotative Meanings of Sensory Factors Associated with Perceived Healthiness and/or Healthy Eating Behavior

2.2.1. Evaluation

2.2.2. Potency

2.2.3. Activity

3. Affective Responses to Sensory Factors Influencing Healthy Eating Behavior

3.1. The Circumplex Model of Affect

3.2. The Affective Responses to Sensory Factors Influencing Healthy Food Evaluations

3.2.1. Valence

3.2.2. Arousal

4. The Perceived Healthiness of Food

4.1. Food Characteristics: What Is in Foods

4.1.1. Naturalness

4.1.2. Less Artificialness

4.1.3. Positive Nutrients

4.1.4. Less Negative Nutrients

4.2. Food Quantity: How Much

4.2.1. The Roles of Sensory Factors in Consumers’ Perception of Food Quantity

4.2.2. Effects of Quantity on Healthy Eating Behavior

5. Health-Related Motivation/Goals

5.1. Health Goals and/or Motives

5.2. Healthy-Tasty Beliefs

6. General Discussion

6.1. Theoretical Contribution to Sensory Marketing

6.2. Psychological Explanations of Our Model: Congruity Theory, Spreading Activation Theory

6.3. Practical Implications

6.4. Future Research Directions

6.5. Implications for Gastronomy

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- GBD 2015 Risk Factors Collaborators. Global, Regional, and National Comparative Risk Assessment of 79 Behavioural, Environmental and Occupational, and Metabolic Risks or Clusters of Risks, 1990–2015: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet 2016, 388, 1659–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rouhani, M.H.; Salehi-Abargouei, A.; Surkan, P.J.; Azadbakht, L. Is There a Relationship between Red or Processed Meat Intake and Obesity? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Obes. Rev. 2014, 15, 740–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swinburn, B.; Kraak, V.; Rutter, H.; Vandevijvere, S.; Lobstein, T.; Sacks, G.; Gomes, F.; Marsh, T.; Magnusson, R. Strengthening of Accountability Systems to Create Healthy Food Environments and Reduce Global Obesity. Lancet 2015, 385, 2534–2545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peeters, A. Obesity and the Future of Food Policies That Promote Healthy Diets. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2018, 14, 430–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Story, M.; Kaphingst, K.M.; Robinson-O’Brien, R.; Glanz, K. Creating Healthy Food and Eating Environments: Policy and Environmental Approaches. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2008, 29, 253–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Temple, N.J. Front-of-Package Food Labels: A Narrative Review. Appetite 2020, 144, 104485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steptoe, A.; Pollard, T.M.; Wardle, J. Development of a Measure of the Motives Underlying the Selection of Food: The Food Choice Questionnaire. Appetite 1995, 25, 267–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steingoltz, M.; Picciola, M.; Wilson, R. Consumer Health Claims 3.0: The next Generation of Mindful Food Consumption; LEK: Boston, MA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kraak, V.I.; Swinburn, B.; Lawrence, M.; Harrison, P. AQ Methodology Study of Stakeholders’ Views about Accountability for Promoting Healthy Food Environments in England through the Responsibility Deal Food Network. Food Policy 2014, 49, 207–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alongi, M.; Anese, M. Re-Thinking Functional Food Development through a Holistic Approach. J. Funct. Foods 2021, 81, 104466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.-J.; Antonelli, M. Conceptual Models of Food Choice: Influential Factors Related to Foods, Individual Differences, and Society. Foods 2020, 9, 1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobal, J.; Bisogni, C.A. Constructing Food Choice Decisions. Ann. Behav. Med. 2009, 38 (Suppl. S1), S37–S46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furst, T.; Connors, M.; Bisogni, C.A.; Sobal, J.; Falk, L.W. Food Choice: A Conceptual Model of the Process. Appetite 1996, 26, 247–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köster, E.P. Diversity in the Determinants of Food Choice: A Psychological Perspective. Food Qual. Prefer. 2009, 20, 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eertmans, A.; Baeyens, F.; Van den Bergh, O. Food Likes and Their Relative Importance in Human Eating Behavior: Review and Preliminary Suggestions for Health Promotion. Health Educ. Res. 2001, 16, 443–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna, A. An Integrative Review of Sensory Marketing: Engaging the Senses to Affect Perception, Judgment and Behavior. J. Consum. Psychol. 2012, 22, 332–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.J.; Mielby, L.A.; Junge, J.Y.; Bertelsen, A.S.; Kidmose, U.; Spence, C.; Byrne, D.V. The Role of Intrinsic and Extrinsic Sensory Factors in Sweetness Perception of Food and Beverages: A Review. Foods 2019, 8, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skaczkowski, G.; Durkin, S.; Kashima, Y.; Wakefield, M. The Effect of Packaging, Branding and Labeling on the Experience of Unhealthy Food and Drink: A Review. Appetite 2016, 99, 219–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spence, C. Behavioural Nudges, Physico-Chemical Solutions, and Sensory Strategies to Reduce People’s Salt Consumption. Foods 2022, 11, 3092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, C. Gastrophysics: Nudging Consumers toward Eating More Leafy (salad) Greens. Food Qual. Prefer. 2020, 80, 103800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motoki, K.; Togawa, T. Multiple Senses Influencing Healthy Food Preference. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 2022, 48, 101223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, C.; Van Doorn, G. Visual Communication via the Design of Food and Beverage Packaging. Cogn. Res. Princ. Implic. 2022, 7, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fenko, A. Influencing Healthy Food Choice through Multisensory Packaging Design. In Multisensory Packaging: Designing New Product Experiences; Velasco, C., Spence, C., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 225–255. ISBN 9783319949772. [Google Scholar]

- Hagen, L. Pretty Healthy Food: How and When Aesthetics Enhance Perceived Healthiness. J. Mark. 2021, 85, 129–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, T.; Lei, J.; Kim, H.J. Adding More Portion-Size Options to a Menu: A Means to Nudge Consumers to Choose Larger Portions of Healthy Food Items. Appetite 2022, 169, 105830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mai, R.; Symmank, C.; Seeberg-Elverfeldt, B. Light and Pale Colors in Food Packaging: When Does This Package Cue Signal Superior Healthiness or Inferior Tastiness? J. Retail. 2016, 92, 426–444. [Google Scholar]

- Motoki, K.; Park, J.; Pathak, A.; Spence, C. Constructing Healthy Food Names: On the Sound Symbolism of Healthy Food. Food Qual. Prefer. 2021, 90, 104157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, N.; Morrin, M.; Kampfer, K. From Glossy to Greasy: The Impact of Learned Associations on Perceptions of Food Healthfulness. J. Consum. Psychol. 2019, 30, 96–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, N.; Morrin, M.; Bublitz, M.G. Flavor Halos Andconsumer Perceptions Offood Healthfulness. Eur. J. Mark. 2019, 53, 685–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng-Li, D.; Andersen, T.; Finlayson, G.; Byrne, D.V.; Wang, Q.J. The Impact of Environmental Sounds on Food Reward. Physiol. Behav. 2021, 245, 113689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Liu, S.Q.; Kandampully, J.; Bujisic, M. How Color Affects the Effectiveness of Taste- versus Health-Focused Restaurant Advertising Messages. J. Advert. 2020, 49, 557–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, C.; Puccinelli, N.M.; Grewal, D.; Roggeveen, A.L. Store Atmospherics: A Multisensory Perspective. Psychol. Mark. 2014, 31, 472–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janiszewski, C.; van Osselaer, S.M.J. Abductive Theory Construction. J. Consum. Psychol. 2022, 32, 175–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grewal, D.; Guha, A.; Satornino, C.B.; Schweiger, E.B. Artificial Intelligence: The Light and the Darkness. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 136, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirtz, J.; Patterson, P.G.; Kunz, W.H.; Gruber, T.; Lu, V.N.; Paluch, S.; Martins, A. Brave New World: Service Robots in the Frontline. J. Serv. Manag. 2018, 29, 907–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osgood, C.E.; Suci, G.J.; Tannenbaum, P.H. The Measurement of Meaning; University of Illinois Press: Champaign, IL, USA, 1957; ISBN 9780252745393. [Google Scholar]

- Snider, J.G.; Osgood, C.E. Semantic Differential Technique; a Sourcebook; Aldine Publishing Company: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1969; ISBN 9780202250250. [Google Scholar]

- Russell, J.A. A Circumplex Model of Affect. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1980, 39, 1161–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- André, Q.; Chandon, P.; Haws, K. Healthy Through Presence or Absence, Nature or Science?: A Framework for Understanding Front-of-Package Food Claims. J. Public Policy Mark. 2019, 38, 172–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandon, P.; Haws, K.; Liu, P. Paths to Healthier Eating: Perceptions and Interventions for Success. J. Assoc. Consum. Res. 2022, 7, 383–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogg, J. A Principal Components Analysis of Semantic Differential Judgements of Single Colors and Color Pairs. J. Gen. Psychol. 1969, 80, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motoki, K.; Park, J.; Pathak, A.; Spence, C. The Connotative Meanings of Sound Symbolism in Brand Names: A Conceptual Framework. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 150, 365–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalton, P.; Maute, C.; Oshida, A.; Hikichi, S.; Izumi, Y. The Use of Semantic Differential Scaling to Define the Multi-Dimensional Representation of Odors. J. Sens. Stud. 2008, 23, 485–497. [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham, M.; Crady, C.A. Identification of Olfactory Dimensions by Semantic Differential Technique. Psychon. Sci. 1971, 23, 387–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sakamoto, M.; Watanabe, J. Bouba/Kiki in Touch: Associations Between Tactile Perceptual Qualities and Japanese Phonemes. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velasco, C.; Woods, A.T.; Marks, L.E.; Cheok, A.D.; Spence, C. The Semantic Basis of Taste-Shape Associations. PeerJ 2016, 4, e1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuldt, J.P. Does Green Mean Healthy? Nutrition Label Color Affects Perceptions of Healthfulness. Health Commun. 2013, 28, 814–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, L.; Lu, J. Eat with Your Eyes: Package Color Influences the Expectation of Food Taste and Healthiness Moderated by External Eating. Mark. Manag. 2015, 25, 71–87. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Liang, J.; Zhou, S.; Kang, Q. The Symmetry Effect: Symmetrical Shapes Increase Consumer’s Health Perception of Food. J. Food Qual. 2022, 2022, 5202087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enquist, M.; Arak, A. Symmetry, Beauty and Evolution. Nature 1994, 372, 169–172. [Google Scholar]

- Auracher, J.; Menninghaus, W.; Scharinger, M. Sound Predicts Meaning: Cross-Modal Associations Between Formant Frequency and Emotional Tone in Stanzas. Cogn. Sci. 2020, 44, e12906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osgood, C.E.; May, W.H.; Miron, M.S.; Miron, M.S. Cross-Cultural Universals of Affective Meaning; University of Illinois Press: Champaign, IL, USA, 1975; ISBN 9780252004261. [Google Scholar]

- Biswas, D.; Szocs, C.; Chacko, R.; Wansink, B. Shining Light on Atmospherics: How Ambient Light Influences Food Choices. J. Mark. Res. 2017, 54, 111–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, E.Y. Brightness Motivates Healthy Behaviors: The Role of Self-Accountability. Environ. Behav. 2021, 54, 363–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Heuvinck, N.; Pandelaere, M. The Light = Healthy Intuition. J. Consum. Psychol. 2022, 32, 326–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Motoki, K.; Pathak, A.; Spence, C. A Sound Brand Name: The Role of Voiced Consonants in Pharmaceutical Branding. Food Qual. Prefer. 2021, 90, 104104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Techawachirakul, M.; Pathak, A.; Calvert, G.A. That Sounds Healthy!: Audio and Visual Frequency Differences in Brand Sound Logos Modify the Perception of Food Healthfulness. Food Qual. Prefer. 2022, 99, 104544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marckhgott, E.; Kamleitner, B. Matte Matters: When Matte Packaging Increases Perceptions of Food Naturalness. Mark. Lett. 2019, 30, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, D.; Szocs, C.; Krishna, A.; Lehmann, D.R. Something to Chew On: The Effects of Oral Haptics on Mastication, Orosensory Perception, and Calorie Estimation. J. Consum. Res. 2014, 41, 261–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamim, A.P.; Mai, R.; Werle, C.O.C. Make It Hot? How Food Temperature (Mis)Guides Product Judgments. J. Consum. Res. 2020, 47, 523–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyama, T.; Tanaka, Y.; Chiba, Y. Affective Dimensions of Colors: A Cross-Cultural Study. Jpn. Psychol. Res. 1962, 4, 78–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Nekolaichuk, C.L.; Jevne, R.F.; Maguire, T.O. Structuring the Meaning of Hope in Health and Illness. Soc. Sci. Med. 1999, 48, 591–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefebvre, S.; Biswas, D. The Influence of Ambient Scent Temperature on Food Consumption Behavior. J. Exp. Psychol. Appl. 2019, 25, 753–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, J.A. Core Affect and the Psychological Construction of Emotion. Psychol. Rev. 2003, 110, 145–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, J.A.; Mehrabian, A. Evidence for a Three-Factor Theory of Emotions. J. Res. Pers. 1977, 11, 273–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yik, M.; Russell, J.A.; Steiger, J.H. A 12-Point Circumplex Structure of Core Affect. Emotion 2011, 11, 705–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuppens, P.; Tuerlinckx, F.; Russell, J.A.; Barrett, L.F. The Relation between Valence and Arousal in Subjective Experience. Psychol. Bull. 2013, 139, 917–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaneko, D.; Toet, A.; Ushiama, S.; Brouwer, A.-M.; Kallen, V.; van Erp, J.B.F. EmojiGrid: A 2D Pictorial Scale for Cross-Cultural Emotion Assessment of Negatively and Positively Valenced Food. Food Res. Int. 2019, 115, 541–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaeger, S.R.; Roigard, C.M.; Jin, D.; Xia, Y.; Zhong, F.; Hedderley, D.I. A Single-Response Emotion Word Questionnaire for Measuring Product-Related Emotional Associations Inspired by a Circumplex Model of Core Affect: Method Characterisation with an Applied Focus. Food Qual. Prefer. 2020, 83, 103805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaltcheva, V.D.; Weitz, B.A. When Should a Retailer Create an Exciting Store Environment? J. Mark. 2006, 70, 107–118. [Google Scholar]

- Vieira, V.A. Stimuli–organism-Response Framework: A Meta-Analytic Review in the Store Environment. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 1420–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motoki, K.; Takahashi, A.; Spence, C. Tasting Atmospherics: Taste Associations with Colour Parameters of Coffee Shop Interiors. Food Qual. Prefer. 2021, 94, 104315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milliman, R.E. The Influence of Background Music on the Behavior of Restaurant Patrons. J. Consum. Res. 1986, 13, 286–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, N.; Epps, H.H. Relationship between Color and Emotion: A Study of College Students. Coll. Stud. J. 2004, 38, 396–405. [Google Scholar]

- Makin, A.D.J.; Wilton, M.M.; Pecchinenda, A.; Bertamini, M. Symmetry Perception and Affective Responses: A Combined EEG/EMG Study. Neuropsychologia 2012, 50, 3250–3261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hur, J.; Jang, S. Anticipated Guilt and Pleasure in a Healthy Food Consumption Context. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 48, 113–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motoki, K.; Takahashi, N.; Velasco, C.; Spence, C. Is Classical Music Sweeter than Jazz? Crossmodal Influences of Background Music and Taste/flavour on Healthy and Indulgent Food Preferences. Food Qual. Prefer. 2022, 96, 104380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, D.; Lund, K.; Szocs, C. Sounds like a Healthy Retail Atmospheric Strategy: Effects of Ambient Music and Background Noise on Food Sales. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2019, 47, 37–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucher, T.; Müller, B.; Siegrist, M. What Is Healthy Food? Objective Nutrient Profile Scores and Subjective Lay Evaluations in Comparison. Appetite 2015, 95, 408–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandon, P.; Wansink, B. The Biasing Health Halos of Fast-Food Restaurant Health Claims: Lower Calorie Estimates and Higher Side-Dish Consumption Intentions. J. Consum. Res. 2007, 34, 301–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Provencher, V.; Polivy, J.; Herman, C.P. Perceived Healthiness of Food. If It’s Healthy, You Can Eat More! Appetite 2009, 52, 340–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Román, S.; Sánchez-Siles, L.M.; Siegrist, M. The Importance of Food Naturalness for Consumers: Results of a Systematic Review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 67, 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, U.T.X.; Chambers, E., 4th. Motivations for Choosing Various Food Groups Based on Individual Foods. Appetite 2016, 105, 204–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandhi, N.; Zou, W.; Meyer, C.; Bhatia, S.; Walasek, L. Computational Methods for Predicting and Understanding Food Judgment. Psychol. Sci. 2022, 33, 579–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadricka, K.; Millet, K.; Verlegh, P.W.J. When Organic Products Are Tasty: Taste Inferences from an Organic = Healthy Association. Food Qual. Prefer. 2020, 83, 103896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amos, C.; King, J.; King, S. The Health Halo of Morality- and Purity-Signifying Brand Names. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2021, 30, 1262–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunz, S.; Haasova, S.; Florack, A. Fifty Shades of Food: The Influence of Package Color Saturation on Health and Taste in Consumer Judgments. Psychol. Mark. 2020, 37, 900–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amar, M.; Gvili, Y.; Tal, A. Moving towards Healthy: Cuing Food Healthiness and Appeal. J. Soc. Mark. 2020, 11, 44–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turnwald, B.P.; Jurafsky, D.; Conner, A.; Crum, A.J. Reading between the Menu Lines: Are Restaurants’ Descriptions of “Healthy” Foods Unappealing? Health Psychol. 2017, 36, 1034–1037. [Google Scholar]

- Motoki, K.; Yamada, A.; Spence, C. Color-nutrient Associations: Implications for Product Design of Dietary Supplements. J. Sens. Stud. 2022, 37, e12777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, S. How Food Shape Influences Calorie Content Estimation: The Biasing Estimation of Calories. J. Food Qual. 2022, 2022, 7676353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.J.; Haws, K.L.; Scherr, K.; Redden, J.P. The Primacy of “What” over “How Much”: How Type and Quantity Shape Healthiness Perceptions of Food Portions. Manag. Sci. 2019, 65, 3353–3381. [Google Scholar]

- Raghubir, P.; Krishna, A. Vital Dimensions in Volume Perception: Can the Eye Fool the Stomach? J. Mark. Res. 1999, 36, 313–326. [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan, D.; Van Ittersum, K.; Craig, A.W.; Romero, M. A Packaged Mindset: How Elongated Packages Induce Healthy Mindsets. Appetite 2020, 150, 104657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagtvedt, H.; Brasel, S.A. Color Saturation Increases Perceived Product Size. J. Consum. Res. 2017, 44, 396–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madzharov, A.V.; Block, L.G. Effects of Product Unit Image on Consumption of Snack Foods. J. Consum. Psychol. 2010, 20, 398–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.; Kahn, B.E. Is Your Product on the Right Side? The “Location Effect” on Perceived Product Heaviness and Package Evaluation. J. Mark. Res. 2009, 46, 725–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, N.; Romero, M. Looks Heavy to Me! The Effects of Product Shadows on Heaviness Perceptions and Product Preferences. J. Advert. 2020, 49, 165–184. [Google Scholar]

- Lowe, M.L.; Haws, K.L. Sounds Big: The Effects of Acoustic Pitch on Product Perceptions. J. Mark. Res. 2017, 54, 331–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, M.; Ringler, C.; Haws, K. An Overture to Overeating: The Cross-Modal Effects of Acoustic Pitch on Food Preferences and Serving Behavior. Appetite 2018, 123, 128–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Qian, D.; Li, O. The Cross-modal Interaction between Sound Frequency and Color Saturation on Consumer’s Product Size Perception, Preference, and Purchase. Psychol. Mark. 2020, 37, 876–899. [Google Scholar]

- English, L.; Lasschuijt, M.; Keller, K.L. Mechanisms of the Portion Size Effect. What Is Known and Where Do We Go from Here? Appetite 2015, 88, 39–49. [Google Scholar]

- Zlatevska, N.; Dubelaar, C.; Holden, S.S. Sizing up the Effect of Portion Size on Consumption: A Meta-Analytic Review. J. Mark. 2014, 78, 140–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holden, S.S.; Zlatevska, N.; Dubelaar, C. Whether Smaller Plates Reduce Consumption Depends on Who’s Serving and Who’s Looking: A Meta-Analysis. J. Assoc. Consum. Res. 2016, 1, 134–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Raghubir, P. Can Bottles Speak Volumes? The Effect of Package Shape on How Much to Buy. J. Retail. 2005, 81, 269–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, B.E.; Wansink, B. The Influence of Assortment Structure on Perceived Variety and Consumption Quantities. J. Consum. Res. 2004, 30, 519–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.; Kahn, B.E.; Unnava, H.R.; Lee, H. A “Wide” Variety: Effects of Horizontal versus Vertical Display on Assortment Processing, Perceived Variety, and Choice. J. Mark. Res. 2016, 53, 682–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, X.; Jiang, J. Healthy-Angular, Unhealthy-Circular: Effects of the Fit between Shapes and Healthiness on Consumer Food Preferences. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 139, 740–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mead, J.A.; Richerson, R. Package Color Saturation and Food Healthfulness Perceptions. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 82, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haasova, S.; Florack, A. Practicing the (un)healthy = Tasty Intuition: Toward an Ecological View of the Relationship between Health and Taste in Consumer Judgments. Food Qual. Prefer. 2019, 75, 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.J.; Haws, K.L. Cutting Calories: The Preference for Lower Caloric Density Versus Smaller Quantities Among Restrained and Unrestrained Eaters. J. Mark. Res. 2020, 57, 948–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, R.; Hoffmann, S. How to Combat the Unhealthy = Tasty Intuition: The Influencing Role of Health Consciousness. J. Public Policy Mark. 2015, 34, 63–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghunathan, R.; Naylor, R.W.; Hoyer, W.D. The Unhealthy = Tasty Intuition and Its Effects on Taste Inferences, Enjoyment, and Choice of Food Products. J. Mark. 2006, 70, 170–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turnwald, B.P.; Crum, A.J. Smart Food Policy for Healthy Food Labeling: Leading with Taste, Not Healthiness, to Shift Consumption and Enjoyment of Healthy Foods. Prev. Med. 2019, 119, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werle, C.O.C.; Trendel, O.; Ardito, G. Unhealthy Food Is Not Tastier for Everybody: The “healthy=tasty” French Intuition. Food Qual. Prefer. 2013, 28, 116–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, C. On the Ethics of Neuromarketing and Sensory Marketing. In Organizational Neuroethics: Reflections on the Contributions of Neuroscience to Management Theories and Business Practices; Martineau, J.T., Racine, E., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 9–29. ISBN 9783030271770. [Google Scholar]

- Aldogan, E.A.; Helmefalk, M. Congruency or Incongruency: A Theoretical Framework and Opportunities for Future Research Avenues. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2021, 31, 606–621. [Google Scholar]

- Turnwald, B.P.; Perry, M.A.; Jurgens, D.; Prabhakaran, V.; Jurafsky, D.; Markus, H.R.; Crum, A.J. Language in Popular American Culture Constructs the Meaning of Healthy and Unhealthy Eating: Narratives of Craveability, Excitement, and Social Connection in Movies, Television, Social Media, Recipes, and Food Reviews. Appetite 2022, 172, 105949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levine, C.S.; Miyamoto, Y.; Markus, H.R.; Rigotti, A.; Boylan, J.M.; Park, J.; Kitayama, S.; Karasawa, M.; Kawakami, N.; Coe, C.L.; et al. Culture and Healthy Eating: The Role of Independence and Interdependence in the United States and Japan. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2016, 42, 1335–1348. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Collins, A.M.; Loftus, E.F. A Spreading-Activation Theory of Semantic Processing. Psychol. Rev. 1975, 82, 407–428. [Google Scholar]

- Schubert, E.; Hargreaves, D.J.; North, A.C. A Dynamically Minimalist Cognitive Explanation of Musical Preference: Is Familiarity Everything? Front. Psychol. 2014, 5, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North, A.C.; Sheridan, L.P.; Areni, C.S. Music Congruity Effects on Product Memory, Perception, and Choice. J. Retail. 2016, 92, 83–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattila, A.S.; Wirtz, J. Congruency of Scent and Music as a Driver of in-Store Evaluations and Behavior. J. Retail. 2001, 77, 273–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helmefalk, M.; Hultén, B. Multi-Sensory Congruent Cues in Designing Retail Store Atmosphere: Effects on Shoppers’ Emotions and Purchase Behavior. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2017, 38, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Laan, L.N.; Papies, E.K.; Hooge, I.T.C.; Smeets, P.A.M. Goal-Directed Visual Attention Drives Health Goal Priming: An Eye-Tracking Experiment. Health Psychol. 2017, 36, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, S.; Park, J. Consumer Evaluation of Healthy, Unpleasant-Tasting Food and the Post-Taste Effect of Positive Information. Food Qual. Prefer. 2018, 66, 107–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng-Li, D.; Mathiesen, S.L.; Chan, R.C.K.; Byrne, D.V.; Wang, Q.J. Sounds Healthy: Modelling Sound-Evoked Consumer Food Choice through Visual Attention. Appetite 2021, 164, 105264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantoja, F.; Borges, A.; Rossi, P.; Yamim, A.P. If I Touch It, I Will like It! The Role of Tactile Inputs on Gustatory Perceptions of Food Items. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 53, 101958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Labroo, A.A. Cueing Morality: The Effect of High-Pitched Music on Healthy Choice. J. Mark. 2020, 84, 130–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarar, N.; Machiels, C.J.A.; Orth, U.R. Shaping up: How Package Shape and Consumer Body Conspire to Affect Food Healthiness Evaluation. Food Qual. Prefer. 2019, 75, 209–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, M.; Biswas, D. Healthy-Left, Unhealthy-Right: Can Displaying Healthy Items to the Left (versus Right) of Unhealthy Items Nudge Healthier Choices? J. Consum. Res. 2016, 43, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.L.; Cho, S.; Seo, H.-S. Effects of Light Color on Consumers’ Acceptability and Willingness to Eat Apples and Bell Peppers. J. Sens. Stud. 2016, 31, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tijssen, I.; Zandstra, E.H.; de Graaf, C.; Jager, G. Why a “light”product Package Should Not Be Light Blue: Effects of Package Colour on Perceived Healthiness and Attractiveness of Sugar-and Fat-Reduced Products. Food Qual. Prefer. 2017, 59, 46–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques da Rosa, V.; Spence, C.; Miletto Tonetto, L. Influences of Visual Attributes of Food Packaging on Consumer Preference and Associations with Taste and Healthiness. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2019, 43, 210–217. [Google Scholar]

- Togawa, T.; Park, J.; Ishii, H.; Deng, X. A Packaging Visual-Gustatory Correspondence Effect: Using Visual Packaging Design to Influence Flavor Perception and Healthy Eating Decisions. J. Retail. 2019, 95, 204–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnurr, B. Too Cute to Be Healthy: How Cute Packaging Designs Affect Judgments of Product Tastiness and Healthiness. J. Assoc. Consum. Res. 2019, 4, 363–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manippa, V.; Giuliani, F.; Brancucci, A. Healthiness or Calories? Side Biases in Food Perception and Preference. Appetite 2020, 147, 104552. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F.; Basso, F. The Peak of Health: The Vertical Representation of Healthy Food. Appetite 2021, 167, 105587. [Google Scholar]

- Motoki, K.; Iseki, S. Evaluating Replicability of Ten Influential Research on Sensory Marketing. Front. Commun. 2022, 7, 231048896. [Google Scholar]

- Biswas, D.; Szocs, C. The Smell of Healthy Choices: Cross-Modal Sensory Compensation Effects of Ambient Scent on Food Purchases. J. Mark. Res. 2019, 56, 123–141. [Google Scholar]

- Motoki, K.; Saito, T.; Nouchi, R.; Kawashima, R.; Sugiura, M. The Paradox of Warmth: Ambient Warm Temperature Decreases Preference for Savory Foods. Food Qual. Prefer. 2018, 69, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Motoki, K.; Park, J.; Togawa, T. The Role of Sensory Cues in Promoting Healthy Eating: A Narrative Synthesis and Gastronomic Implications. Gastronomy 2025, 3, 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/gastronomy3020006

Motoki K, Park J, Togawa T. The Role of Sensory Cues in Promoting Healthy Eating: A Narrative Synthesis and Gastronomic Implications. Gastronomy. 2025; 3(2):6. https://doi.org/10.3390/gastronomy3020006

Chicago/Turabian StyleMotoki, Kosuke, Jaewoo Park, and Taku Togawa. 2025. "The Role of Sensory Cues in Promoting Healthy Eating: A Narrative Synthesis and Gastronomic Implications" Gastronomy 3, no. 2: 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/gastronomy3020006

APA StyleMotoki, K., Park, J., & Togawa, T. (2025). The Role of Sensory Cues in Promoting Healthy Eating: A Narrative Synthesis and Gastronomic Implications. Gastronomy, 3(2), 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/gastronomy3020006