Investigation of Aeromycoflora in the Library and Reading Room of Midnapore College (Autonomous): Impact on Human Health

Abstract

1. Introduction

- To determine the qualitative and quantitative composition of indoor airborne fungi within the Central Library of Midnapore College (Autonomous).

- To investigate the association between fungal aerospora exposure and allergenic respiratory diseases through a hospitalization survey.

- To assess the allergenicity of dominant fungal species present in the indoor environment using both in vitro and in vivo diagnostic methods.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Procedures

Study Area

2.2. Methodology

2.3. Counting of CFUs and Establishing Pure Culture

2.4. Methodological Limitations

2.5. Morphological Identification of Fungal Colonies

2.6. Clinical Study, Patient Selection, and Sample Collection

2.7. Patient Selection and Precautions Adopted Before Skin Prick Test

- Patients were not allowed to take any medications for 24 h prior to the skin prick test because certain medications have been shown to reduce skin sensitivity, resulting in false negative results ([56]; AAOA-SPT 2015).

2.8. Fungal Pure Culture and Antigen Extraction and Estimation of Total Protein from Spores of Selected Fungus

2.9. SPT, Sensitivity Grading, Sera Collection, and ELISA (In Vitro Test)

- Skin prick test: The enlisted clinician of the clinics performed a skin prick test (SPT) on sensitive patients with fungal crude antigenic extract (1:10 w/v) to get a general idea about the relationship between allergic symptoms and fungal spore occurrence, using the EAACI method [46].

- Sensitive patients provided written consent to draw 2 mL of blood. Serum was separated and stored at −20 °C for future investigations.

- Sera from two non-atopic individuals were taken as a negative control.

- The individual clinics’ ethical committees authorized the entire study.

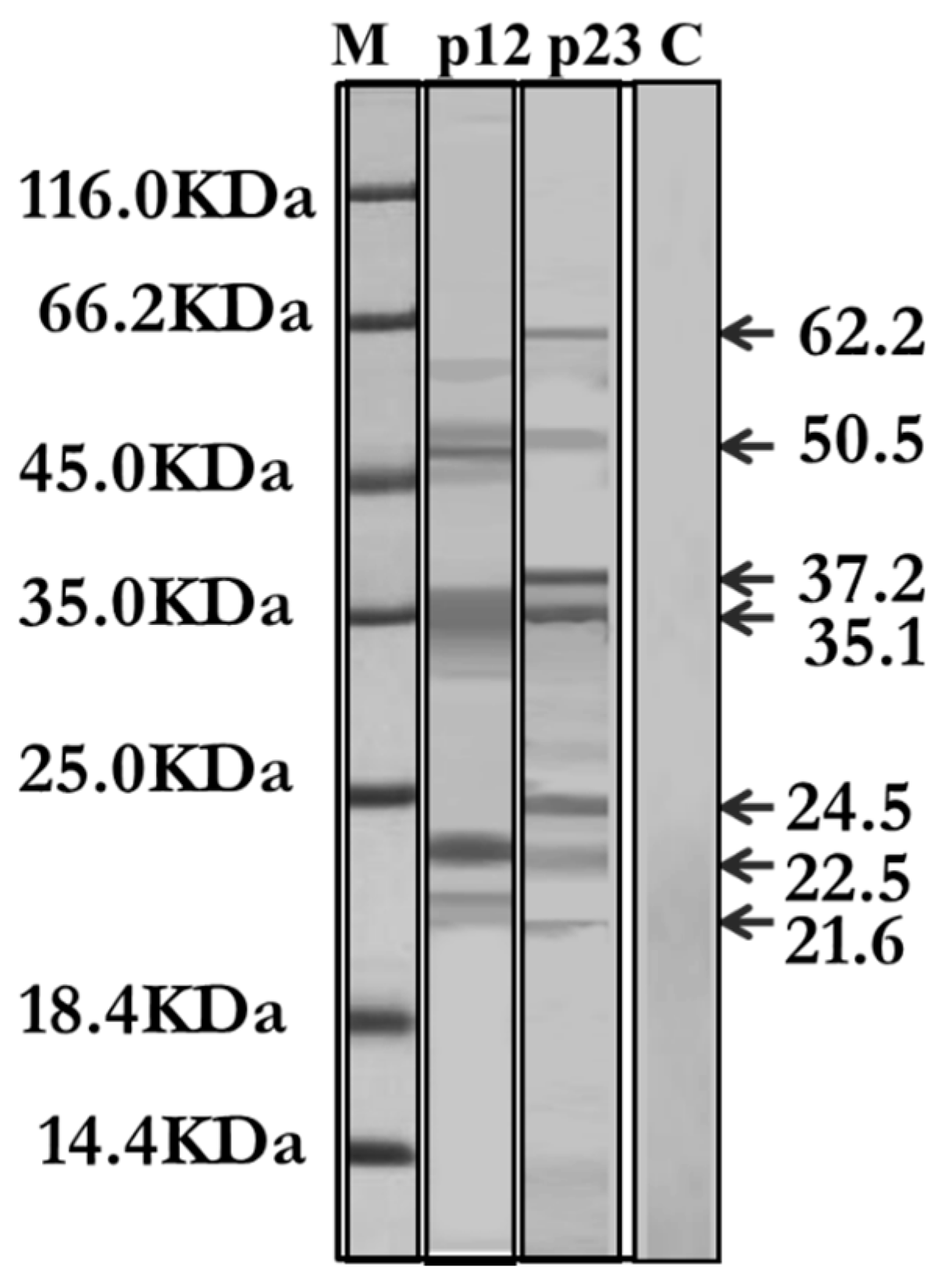

2.10. Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate–Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (SDS–PAGE) and IgE-Specific Immunoblotting

3. Result and Discussion

3.1. Aeromycological Sampling: Quantitative and Qualitative Evaluation of the Aerial Fungal Spores

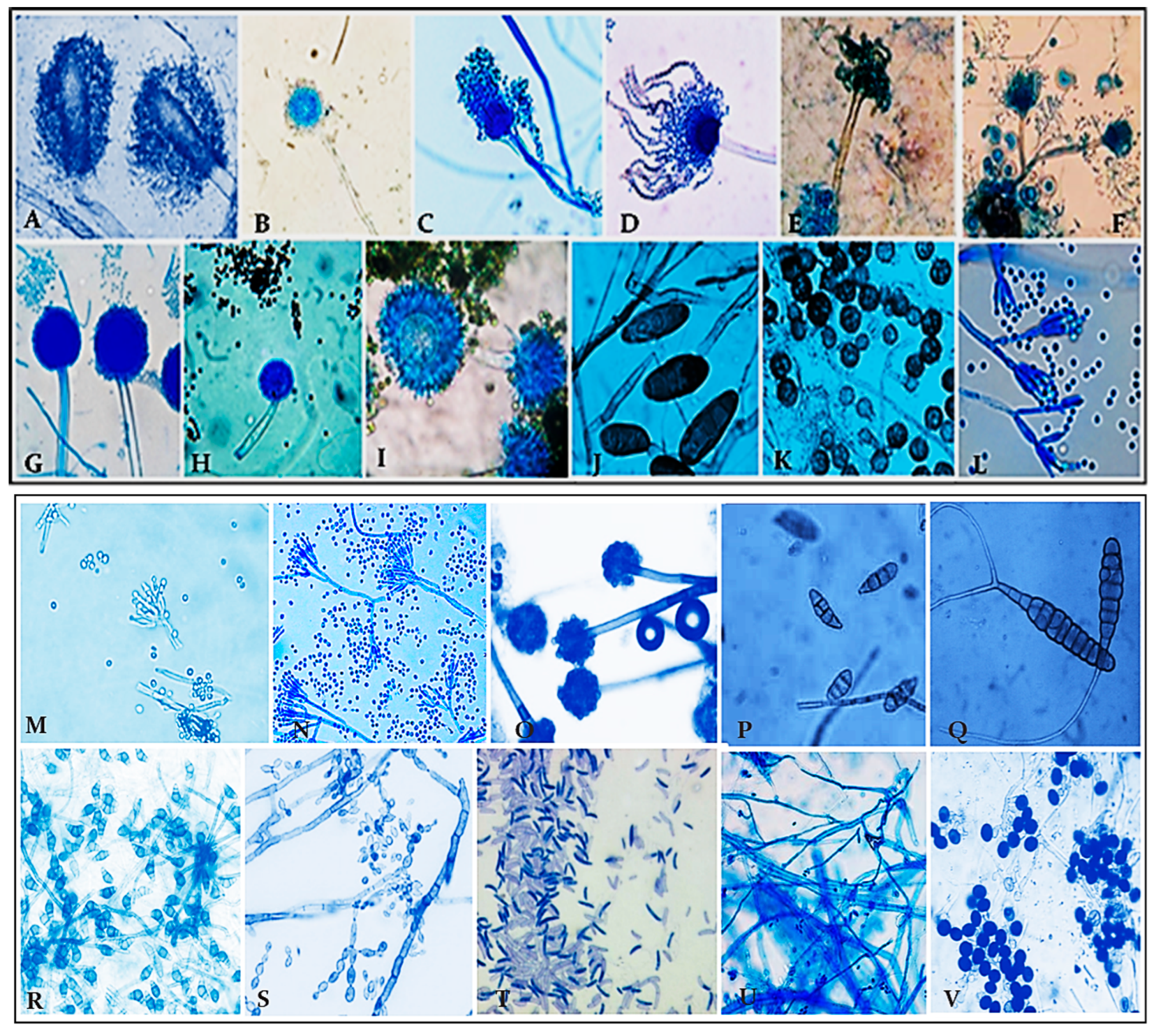

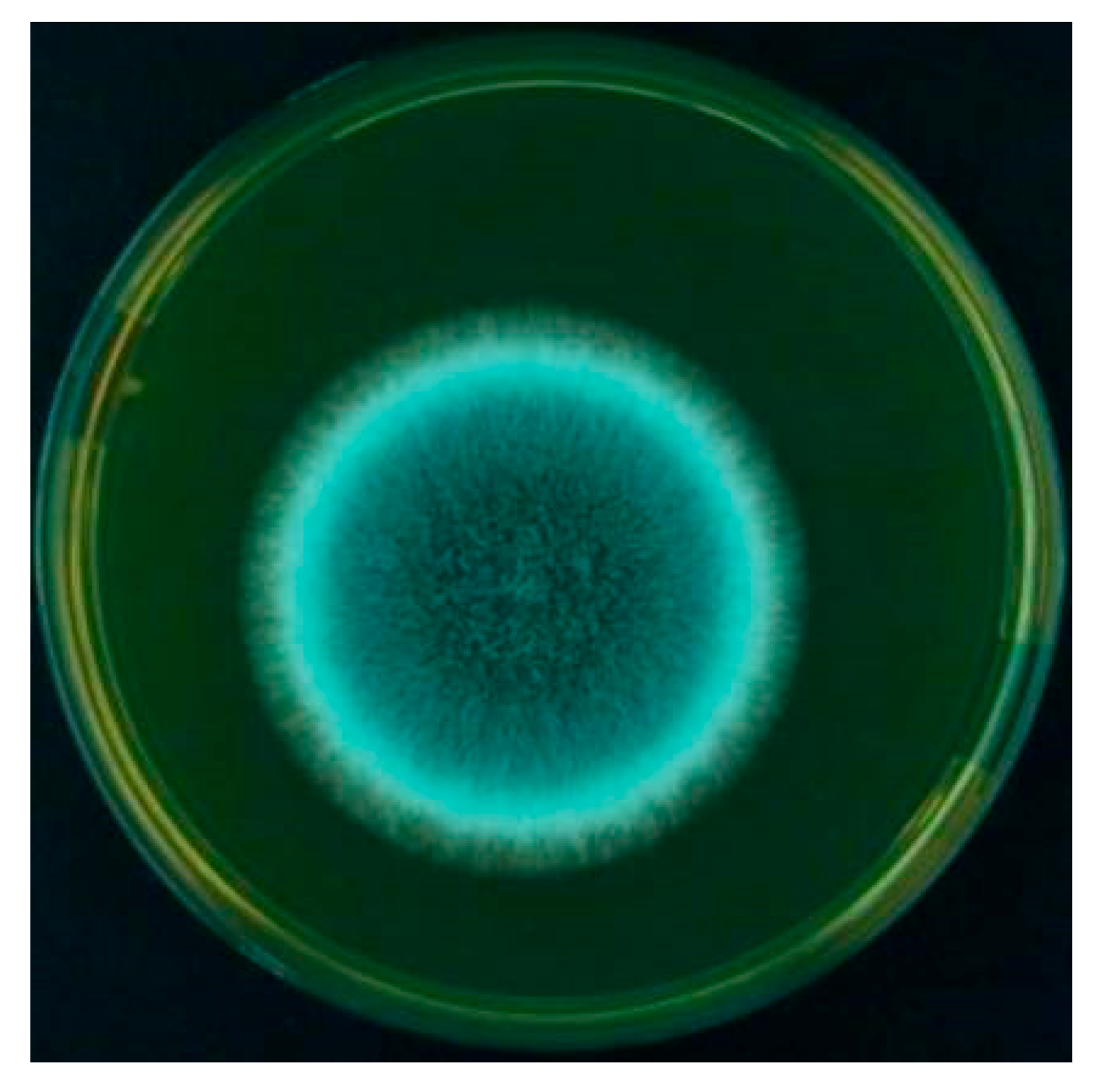

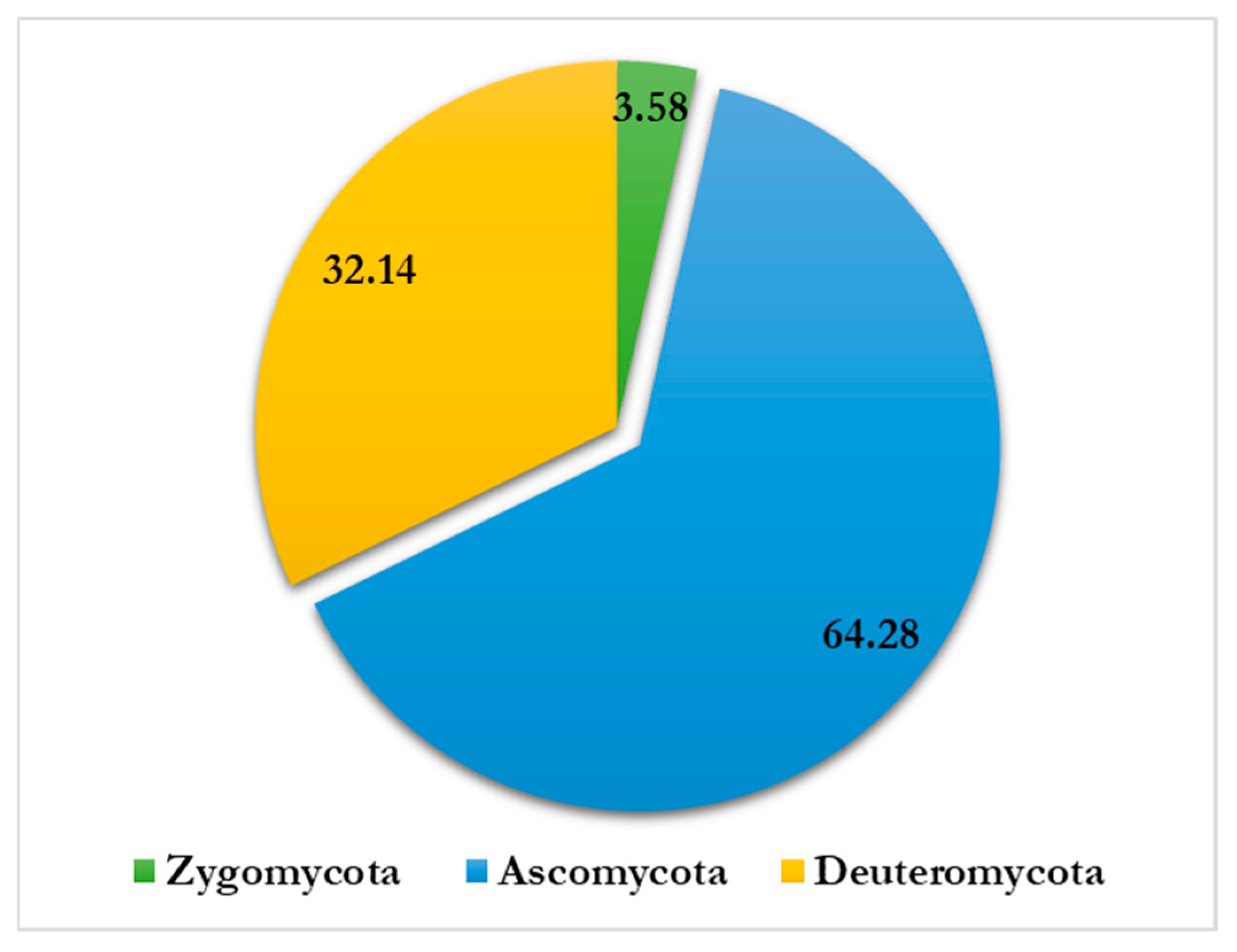

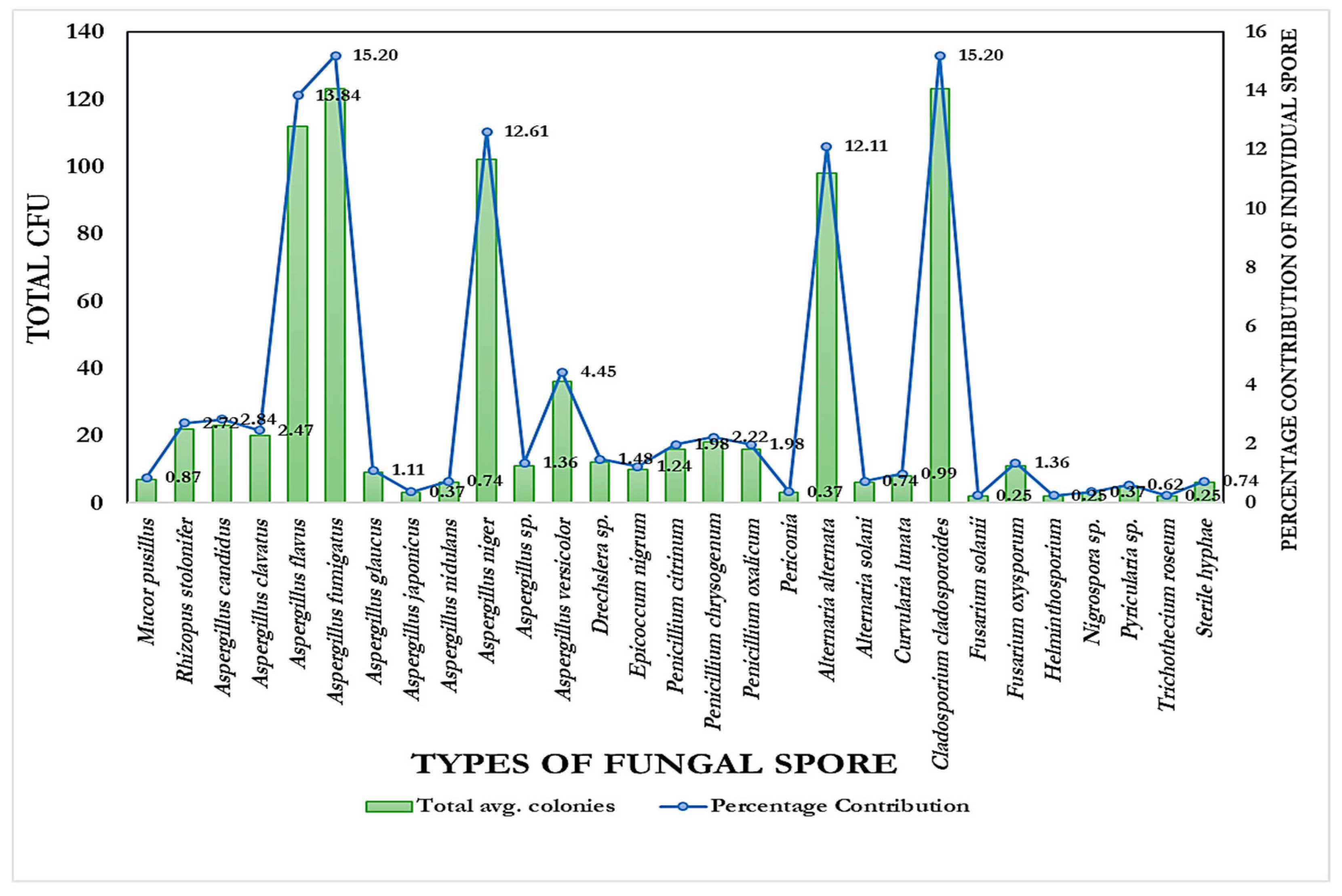

- Altogether, 815 colonies falling under 15 genera and 28 species have been recorded by the culture plate exposure method (Figure 2). Ascomycota dominated more than half of the colonies recorded, followed by Zygomycota and Deuteromycota, while Oomycota had the fewest colonies. A significant number of colonies prevailed in the onset of summer, while a lesser number occurred in winter during the period of study.

- Deuteromycota dominated with 32.14% airspora exhibiting the highest concentrations, followed by Ascomycota with 64.28% air spora. Zygomycota had the least count of 3.58%, while Sterile mycelia contributed 0.74%. Fungal spores from Basidiomycota did not appear on nutrient jelly (Table 1). It is in agreement with the results of Adams et al. (2013) [79], who obtained a higher count of fungal isolates in the indoor environment of a library for Deuteromycota.

- The count of isolates and their concentration in the indoor environment varied with climatic changes. Of the total isolates, Deuteromycota exhibited the highest count of isolates, followed by Ascomycota and Zygomycota. The lowest count of isolates was associated with Sterile mycelia (Figure 7 and Figure 8). Members of Deuteromycota produce enormous resistant thick-walled conidia asexually and remain dormant in an unfavorable indoor environment for a longer duration and are able to germinate on the onset of optimum temperature and high relative humidity [68,80,81].

3.1.1. Relationship Between Fungal Spore Concentrations and Atopic Sensitization Among the Visiting Students: Determination of Significant Predictors Through Multiple Regression Model

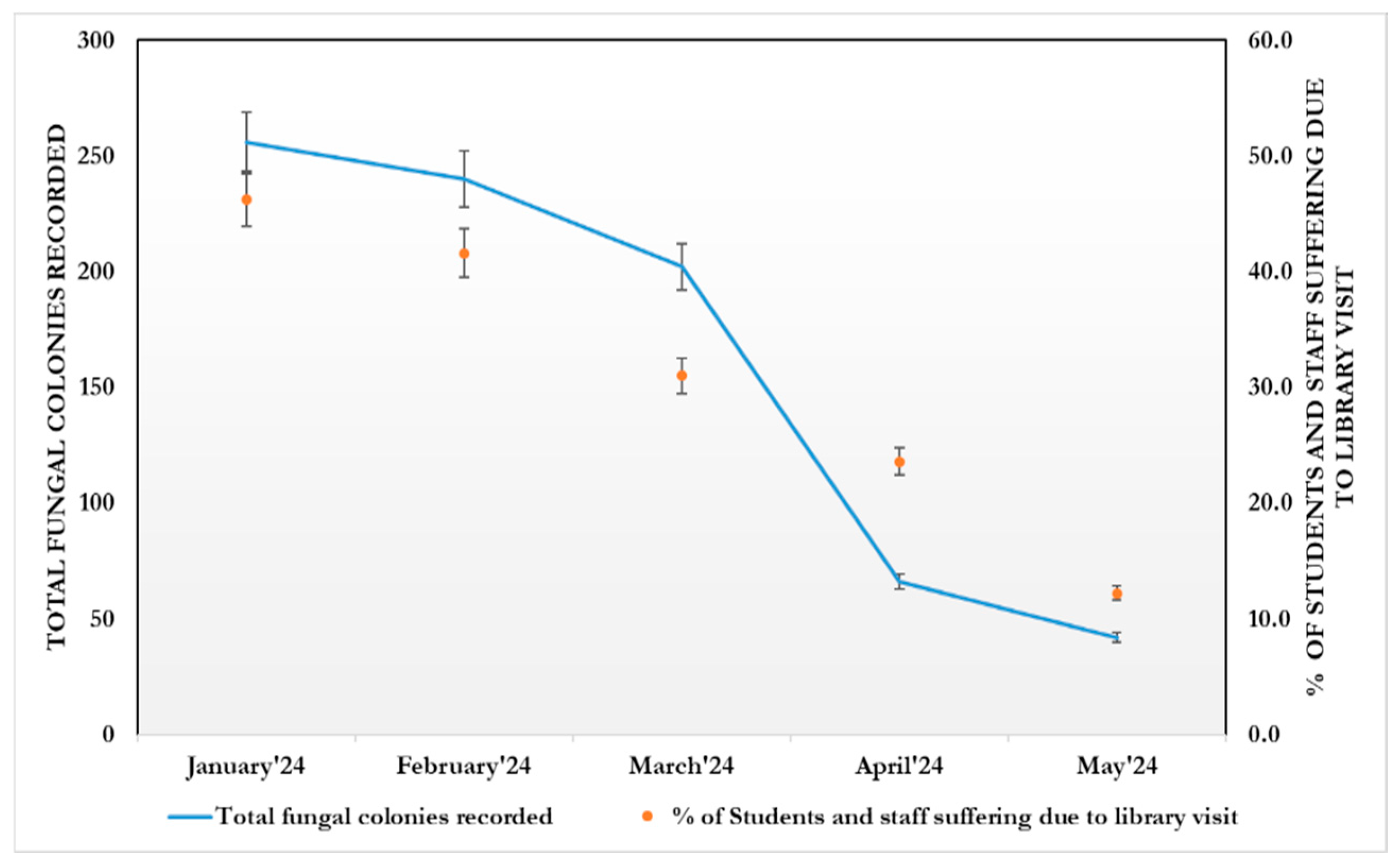

- Fungal spore concentration is highest in January due to the dry atmosphere, and gradually decreases from March due to higher temperatures and high moisture content. Thus, fungal spore concentration is positively correlated with temperature and rainfall.

- Exposure to indoor airborne inhalant fungal allergens developed respiratory symptoms and allergies among the students and staff.

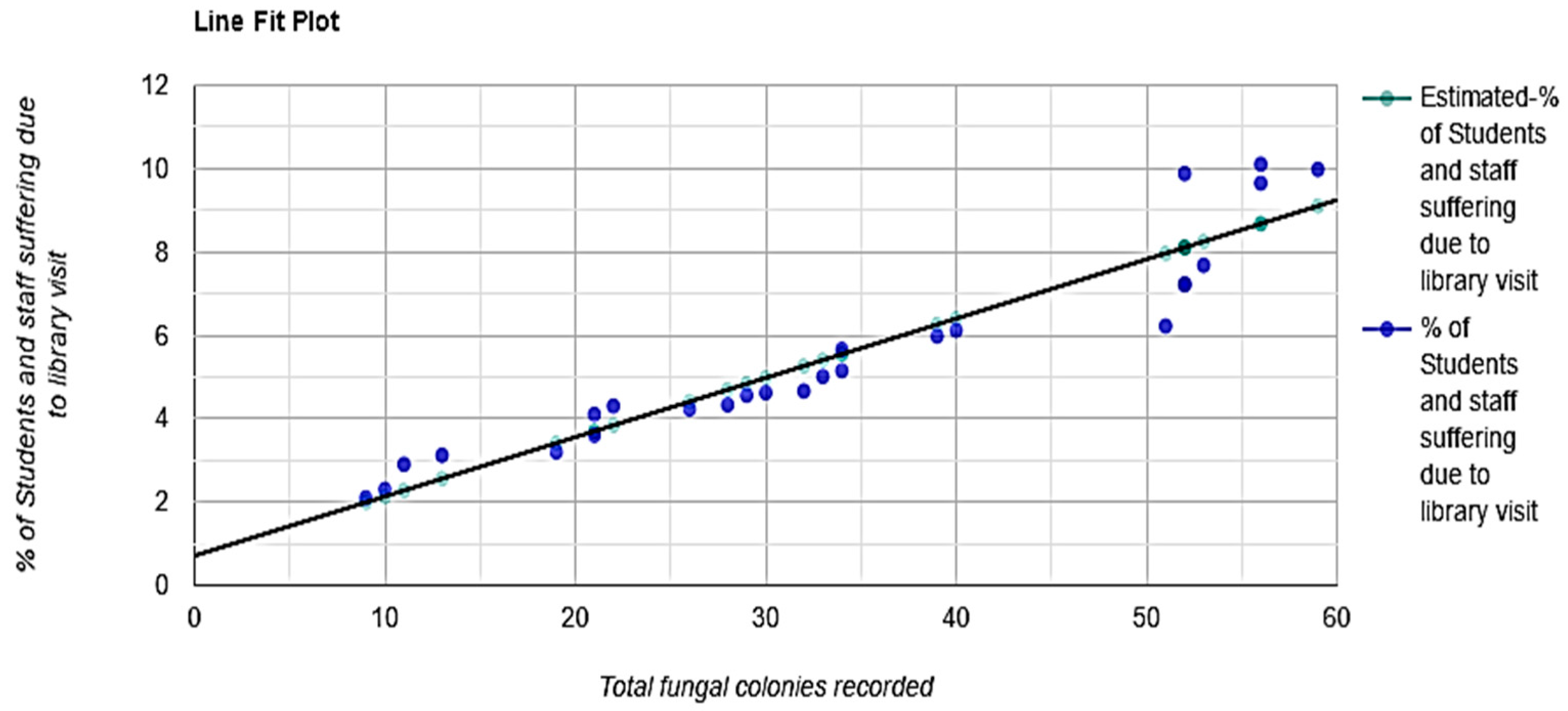

3.1.2. The Interpretation of Statistical Analysis (Figure 10)

- R-Squared (R2) equals 0.89. This means that 89% of the variability of % of students and staff suffering due to library visits is explained by the total fungal colonies recorded (Figure 11).

- Correlation (r) equals 0.9485. This means that there is a very strong direct relationship between the total fungal colonies recorded and % of students and staff suffering due to library visits.

- Overall regression: right-tailed, F(1,24) = 215.1586, p-value = 1.765 × 10−13. Since p-value < α (0.05), we reject H0. (Table 2).

- The linear regression model, Y = b0 + b1X + ε, provides a better fit than the model without the independent variable, resulting in Y = b0 + ε.

- The slope (b1): two-tailed, T(24) = 14.6683, p-value = 1.765 × 10−13. For one predictor, it is the same as the p-value for the overall model.

- The y-intercept (b0): two-tailed, T(24) = 1.9595, p-value = 0.06177. Hence, b0 is not significantly different from zero. It is still most likely recommended not to force b0 to be zero.Figure 10. Generalized linear regression analysis: The total fungal load in the intramural environment vs. students and staff who visited the library during the study period. The straight line that represents the relationship between a dependent variable (Y) and an independent variable (X) in a linear regression equation.Figure 10. Generalized linear regression analysis: The total fungal load in the intramural environment vs. students and staff who visited the library during the study period. The straight line that represents the relationship between a dependent variable (Y) and an independent variable (X) in a linear regression equation.Figure 11. Total fungal colonies recorded predicted % of Students and staff suffering due to library visit, R2 = 0.89, F(1,24) = 237.68, p < 0.001, β = 0.14, p < 0.001, α = 0.7, p = 0.052.Figure 11. Total fungal colonies recorded predicted % of Students and staff suffering due to library visit, R2 = 0.89, F(1,24) = 237.68, p < 0.001, β = 0.14, p < 0.001, α = 0.7, p = 0.052.

3.2. Selection of Fungal Species for Immune-Biochemical Analysis

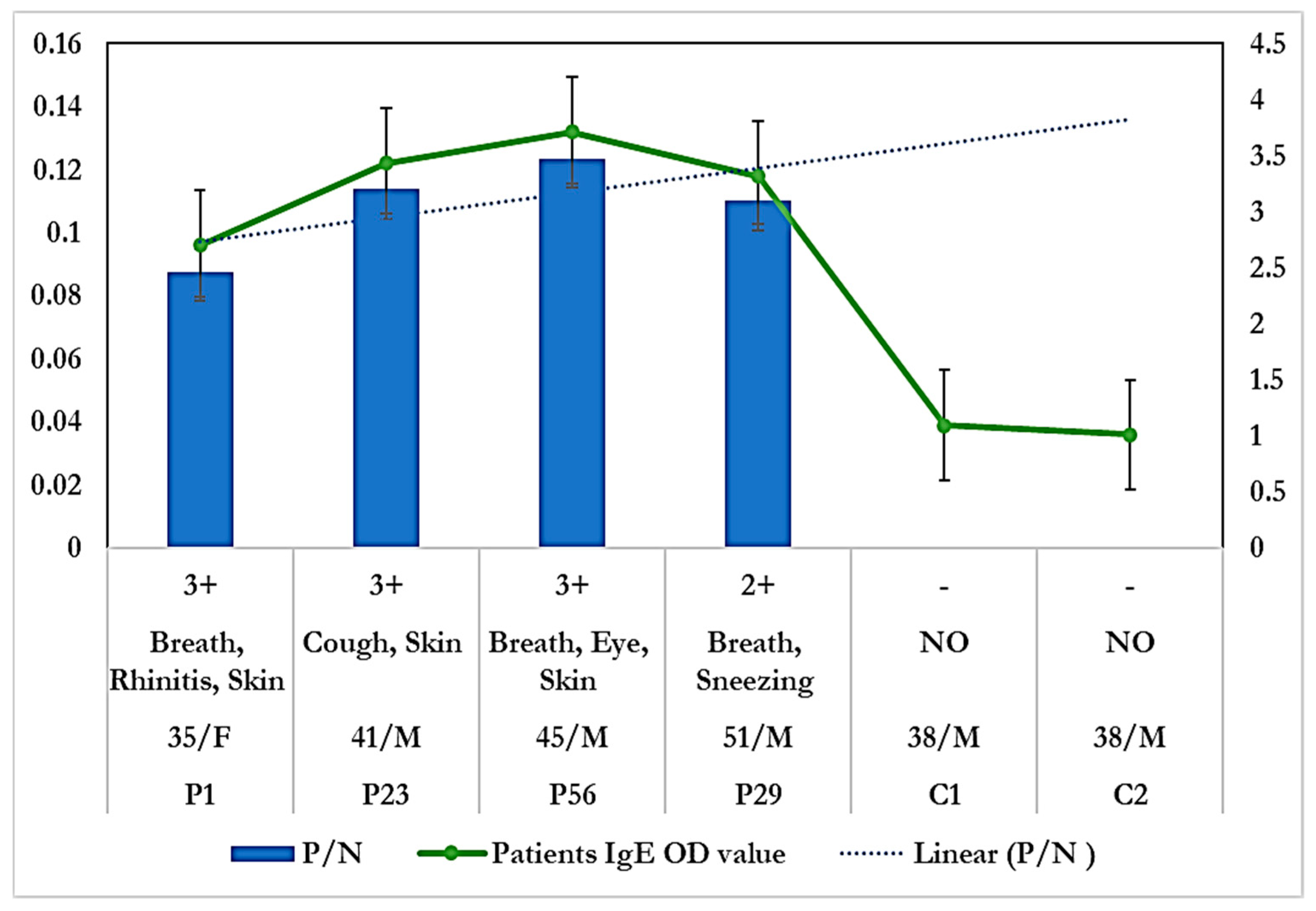

3.2.1. Allergenicity Assessment by Skin Prick Test

3.2.2. Specific IgE Estimation

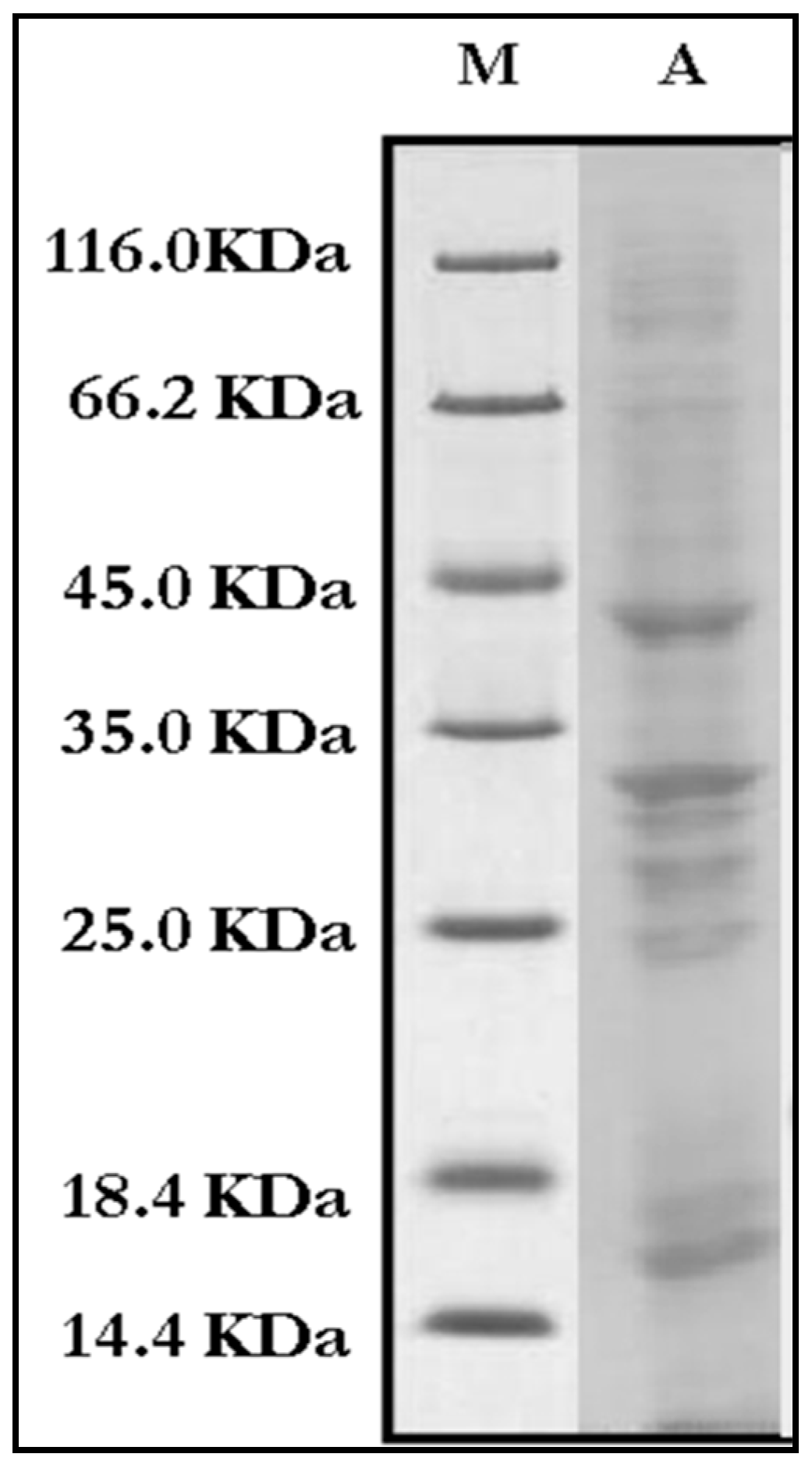

3.2.3. Immuno-Biochemical Study of Mycelial Crude Proteins/Antigens

3.2.4. IgE-Specific Immunoblotting

4. Conclusions

Study Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kalaskar, P.G.; Zodpe, S.N. Biodeterioration of Library Resources and Possible Approaches for Their Control. Int. J. Appl. Res. 2016, 2, 25–33. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, J. Analysis of Printing and Writing Papers by Using Direct Analysis in Real Time Mass Spectrometry. Int. J. Mass Spectrom. 2011, 301, 109–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byers, B. A Simple and Practical Fumigation System. Newsletter 1983, 7, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Maggi, O.; Persiani, A.M.; Gallo, F.; Valenti, P.; Pasquariello, G.; Sclocchi, M.C.; Scorrano, M. Airborne Fungal Spores in Dust Present in Archives: Proposal for a Detection Method New for Archival Materials. Aerobiologia 2000, 16, 429–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koestler, R.J. When Bad Things Happen to Good Art. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2000, 46, 259–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamsian, A.; Fata, A.; Mohajeri, M.; Ghazvini, K. Fungal Contaminations in Historical Manuscripts at Astan Quds Museum Library, Mashhad, Iran. Int. J. Agric. Biol. 2008, 8, 420–422. [Google Scholar]

- Bankole, O.M. A Review of Biological Deterioration of Library Materials and Possible Control Strategies in the Tropics. Lib. Rev. 2010, 59, 414–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guggenheim, S.; Martin, R.T. Definition of Clay and Clay Mineral: Journal Report of the AIPEA Nomenclature and CMS Nomenclature Committees. Clays Clay Miner. 1995, 43, 255–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, K.; Raha, S.; Majumdar, M.R. Measuring Indoor Fungal Contaminants in Rural West Bengal, India, with Reference to Allergic Symptoms. Indoor Built Environ. 2001, 10, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabee, W.; Roy, D.N. Modeling the Role of Paper Mill Sludge in the Organic Carbon Cycle of Paper Products. Environ. Rev. 2003, 11, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugauskas, A.; Kriktaponis, A. Microscopic Fungi Found in the Libraries of Vilnius and Factors Affecting Their Development. Indoor Built Environ. 2004, 13, 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doncea, S.M.; Ion, R.M.; Fierascui, R.C.; Bacalum, E.; Bunaciu, A.A.; Aboul-Enein, H.Y. Spectral Methods for Historical Paper Analysis: Composition and Age Approximation. Instrum. Sci. Technol. 2010, 38, 96–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Area, M.C.; Cheradame, H. Paper Aging and Degradation: Recent Findings and Research Methods. Bioresources 2011, 6, 5307–5337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karbowska-Berent, J.; Górny, R.L.; Strzelczyk, A.B.; Wlazło, A. Airborne and Dust-Borne Microorganisms in Selected Polish Libraries and Archives. Build. Environ. 2011, 46, 1872–1879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furlong-Silva, J.; Cook, P.C. Fungal-mediated lung allergic airway disease: The critical role of macrophages and dendritic cells. PLoS Pathog. 2022, 18, e1010608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henniges, U.; Schiehsser, S.; Ahn, K.; Hofinger, A.; Geschke, A.; Potthast, A.; Rosenau, T. On the Structure of the Active Compound in Mass Deacidification of Paper. Holzforschung Int. J. Biol. Chem. Phys. Technol. Wood 2012, 66, 447–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karmakar, B.; Sen Gupta, K.; Kaur, A.; Roy, A.; Gupta-Bhattacharya, S. Fungal Bioaerosol in Multiple Micro-Environments from Eastern India: Source, Distribution, and Health Hazards. SN Appl. Sci. 2020, 2, 565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalik, R. Microbiodeterioration of Library Materials. Part 1. Restaurator 1980, 4, 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zyska, B. Fungi Isolated from Library Materials: A Review of the Literature. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 1997, 40, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumdar, M.R.; Hazare, S. Assessment of Fungal Contaminants in the Libraries of Presidency College, Kolkata. Indian. J. Aerobiol. 2005, 18, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Adhikari, A.; Sen, M.M.; Gupta-Bhattacharya, S.; Chanda, S. Airborne viable, non-viable, and allergenic fungi in a rural agricultural area of India: A 2-year study at five outdoor sampling stations. Sci. Total Environ. 2004, 326, 123–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumdar, M.R.; Bhattacharya, K. Measurement of Indoor Fungal Contaminants Causing Allergy among the Workers of Paper Related Industries of West Bengal, India. Indoor Built Environ. 2004, 13, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kauffman, H.F.; Tomée, J.F.; van de Riet, M.A.; Timmerman, A.J.; Borger, P. Protease-Dependent Activation of Epithelial Cells by Fungal Allergens Leads to Morphologic Changes and Cytokine Production. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2000, 105, 1185–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischer, G.; Schwalbe, R.; Möller, M.; Ostrowski, R.; Dott, W. Species-Specific Production of Microbial Volatile Organic Compounds (MVOCs) by Airborne Fungi from a Compost Facility. Chemosphere 1999, 39, 795–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamamoto, N.; Bibby, K.; Qian, J.; Hospodsky, D.; Rismani-Yazdi, H.; Nazaroff, W.W.; Peccia, J. Particle-Size Distributions and Seasonal Diversity of Allergenic and Pathogenic Fungi in Outdoor Air. ISME J. 2012, 6, 1801–1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon-Nobbe, B.; Denk, U.; Poll, V.; Rid, R.; Breitenbach, M. The Spectrum of Fungal Allergy. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 2008, 145, 58–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Hoog, G.S.; Guarro, J.; Gene, J.; Figueras, M.J. Atlas of Clinical Fungi, 2nd ed.; Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Tariq, S.M.; Matthews, S.M.; Stevens, M.; Hakim, E.A. Sensitization to Alternaria and Cladosporium by the Age of 4 Years. Clin. Exp. Allergy 1996, 26, 794–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvaggio, J.; Aukrust, L. Postgraduate Course Presentations. Mold-Induced Asthma. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 1981, 68, 327–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corey, J.P.; Kaiseruddin, S.; Gungor, A. Prevalence of Mold-Specific Immunoglobulins in a Midwestern Allergy Practice. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 1997, 123, 283–289. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez, M.; Salvaggio, J.E. Mold-Sensitive Asthma. Clin. Rev. Allergy 1985, 3, 183–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, K.H.; Shen, J.J. Prevalence of childhood asthma in Taipei, Taiwan, and other Asian Pacific countries. J. Asthma 1988, 25, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teresa, E.T.; Curin, M.; Valenta, R.; Swoboda, I. Mold Allergens in Respiratory Allergy: From Structure to Therapy. Allergy Asthma Immunol. Res. 2015, 7, 205–220. [Google Scholar]

- Kortekangas-Savolainen, O.; Lammintausta, K.; Kalimo, K. Skin Prick Test Reactions to Brewer’s Yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) in Adult Atopic Dermatitis Patients. Allergy 1993, 48, 147–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denning, D.W.; O’Driscoll, B.R.; Hogaboam, C.M.; Bowyer, P.; Niven, R.M. The Link between Fungi and Severe Asthma: A Summary of the Evidence. Eur. Respir. J. 2006, 27, 615–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bush, R.K.; Prochnau, J.J. Alternaria-Induced Asthma. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2004, 113, 227–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neukirch, C.; Henry, C.; Leynaert, B.; Liard, R.; Bousquet, J.; Neukirch, F. Is Sensitization to Alternaria alternata a Risk Factor for Severe Asthma? A Population-Based Study. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 1999, 103, 709–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niedoszytko, M.; Chelminska, M.; Jassem, E.; Czestochowska, E. Association between Sensitization to Aureobasidium pullulans (Pullularia sp.) and Severity of Asthma. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2007, 98, 153–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Reddy, L.V.; Sochanik, A.; Kurup, V.P. Isolation and Characterization of a Recombinant Heat Shock Protein of Aspergillus fumigatus. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 1993, 91, 1024–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Licorish, K.; Novey, H.S.; Kozak, P.; Fairshter, R.D.; Wilson, A.F. Role of Alternaria and Penicillium Spores in the Pathogenesis of Asthma. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 1998, 76, 819–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, L.S. A Three-Year Survey of Micro Fungi in the Air of Copenhagen. Allergy 1981, 36, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nussbaum, F. Variation in the airborne fungal spore population of the Tuscarawas Valley II. Mycopathologia 1991, 116, 181–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Hafez, S.I.I.; El-Said, A.H.M.; Gherbawy, Y.A.M.H. Mycoflora of leaf surface, stem, bagasse, and juice of adult sugarcane (Saccharum officinarum L.) plant and cellulolytic ability in Egypt. Bull. Fac. Sci. Assiut Univ. 1995, 24, 113–130. [Google Scholar]

- Shams-Ghahfarokhi, M.; Aghaei-Gharehbolagh, S.; Aslani, N.; Razzaghi-Abyaneh, M. Investigation on distribution of airborne fungi in outdoor environment in Tehran, Iran. J. Environ. Health Sci. Eng. 2014, 12, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalbende, S.; Dalal, L.; Bhowal, M. The Monitoring of Airborne Mycoflora in Indoor Air Quality of Library. J. Nat. Prod. Plant Resour. 2012, 2, 675–679. [Google Scholar]

- Karmakar, B.; Saha, B.; Jana, K.; Gupta Bhattacharya, S. Identification and biochemical characterization of Asp t 36, a new fungal allergen from Aspergillus terreus. J. Biol. Chem. 2020, 295, 17852–17864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, M.K.; Shivpuri, D.N.; Mukerji, K.G. Studies on the allergenic fungal spores of the Delhi, India, metropolitan area. J. Allergy 1969, 44, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, M.B.; Ellis, J.P. Fungi without Gills (Hymenomycetes and Gasteromycetes): An Identification Handbook; Chapman and Hall: London, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, C.; Johnson, E.M. Identification of Pathogenic Fungi; Wiley: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Sreeramulu, T.; Ramalingam, A. A Two-Year Study of the Air-Spore of a Paddy Field near Visakhapatnam. Indian J. Agric. Sci. 1966, 36, 111–132. [Google Scholar]

- Ainsworth, G.C.; Sparrow, F.K.; Sussman, A.S. The fungi, an advanced treatise. Yale J. Biol. Med. 1973, 38, 485–486. [Google Scholar]

- El Jaddaoui, I.; Ghazal, H.; Bennett, J.W. Mold in Paradise: A Review of Fungi Found in Libraries. J. Fungi 2023, 9, 1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.; Singh, S.; Asif, A.R.; Oellerich, M.; Sharma, G.L. Allergic Aspergillosis and the Antigens of Aspergillus fumigatus. Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 2014, 15, 403–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sengupta, K.; Karmakar, B.; Gupta-Bhattacharya, S. A Comparative Study on Airborne Non-Viable and Viable Fungal Spores of Urban and Rural Area of the Gangetic Plains of West Bengal through Aerobiological Survey. Indian J. Aerobiol. 2015, 28, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Pawankar, R.; Canonica, G.; Holgate, S.; Lockey, R. WAO White Book on Allergy; World Allergy Organization: Milwaukee, WI, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Heinzerling, L.; Meri, A.; Bergmann, K.C.; Bresciani, M.; Burbach, G.; Darsow, U. The Skin Prick Test—European Standards. Clin. Transl. Allergy 2013, 3, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernstein, I.L.; Li, J.T.; Bernstein, D.I.; Hamilton, R.; Spector, S.L.; Tan, R. Allergy Diagnostic Testing: An Updated Practice Parameters. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2018, 103, S1–S148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fatteh, S.; Rekkerth, D.J.; Hadley, J.A. Skin prick/puncture testing in North America: A call for standards and consistency. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol. 2014, 10, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sircar, G.; Bhowmik, M.; Sarkar, R.K.; Najafi, N.; Dasgupta, A.; Focke-Tejkl, M.; Flicker, S.; Mittermann, I.; Valenta, R.; Bhattacharya, K.; et al. Molecular characterization of a fungal cyclophilin allergen Rhi o 2 and elucidation of antigenic determinants responsible for IgE–cross-reactivity. J. Biol. Chem. 2020, 295, 2736–2748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreborg, S. Methods for Skin Testing. Allergy 1989, 44, 22–30. [Google Scholar]

- Sircar, G.; Saha, B.; Mandal, R.S.; Pandey, N.; Saha, S.; Bhattacharya, S.G. Purification, Cloning and Immuno-Biochemical Characterization of a Fungal Aspartic Protease Allergen Rhi o 1 from the Airborne Mold Rhizopus oryzae. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0144547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shivpuri, D.N. Clinically Important Pollen, Fungal and Insect Allergens for Nasobronchial Allergy Patients in India. Asp. Allergy Appl. Immunol. 1980, 13, 19–23. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, B.; Oellerich, M.; Kumar, R.; Kumar, M.; Bhadoria, D.P.; Reichard, U.; Gupta, V.K.; Sharma, G.L.; Asif, A.R. Immuno-reactive molecules identified from the secreted proteome of Aspergillus fumigatus. J. Proteome Res. 2010, 9, 5517–5529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laemmli, U.K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 1970, 227, 680–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sambrook, J.; Russell, D.W. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual, 4th ed.; Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press: Cold Spring Harbor, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Chelak, E.P.; Sharma, K. Aeromycological Study of Chandragiri Hill Top, Chhattisgarh. Int. Multidiscip. Res. J. 2012, 2, 15–16. [Google Scholar]

- Karvala, K.; Toskala, E.; Luukkonen, R.; Lappalainen, S.; Uitti, J.; Nordman, H. New-Onset Adult Asthma in Relation to Damp and Moldy Workplaces. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2010, 83, 855–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy, S.; Saha, B.; Bhattacharya, S.B. Identifying novel allergens from a common indoor mould Aspergillus ochraceus. J. Proteom. 2021, 238, 104156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, M.; Ribeiro, H.; Delgado, J.L.; Abreu, I. The Effect of Meteorological Factors on Airborne Fungal Spore Concentration in Two Areas Differing in Urbanisation Level. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2009, 53, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nambu, M.; Kouno, H.; Aihara-Tanaka, M.; Shirai, H.; Takatori, K. Detection of Fungi in Indoor Environments and Fungus-Specific IgE Sensitization in Allergic Children. World Allergy Organ. J. 2009, 2, 208–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denning, D.W.; Pashley, C.; Hartl, D.; Wardlaw, A.; Godet, C.; Di Giacco, S.; Sergejeva, S. Fungal Allergy in Asthma—State of the Art and Research Needs. Clin. Transl. Allergy 2014, 4, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crameri, R.; Garbani, M.; Rhyner, C.; Huitema, C. Fungi: The Neglected Allergenic Sources. Allergy 2014, 69, 176–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.; Christy Sadreameli, S.; Curtin-Brosnan, J.; Grant, T.; Phipatanakul, W.; Perzanowski, M.; Balcer-Whaley, S.; Peng, R.; Newman, M.; Cunningham, A.; et al. Do Baseline Asthma and Allergic Sensitization Characteristics Predict Responsiveness to Mouse Allergen Reduction? J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2020, 8, 596–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Ana, S.G.; Torres-Rodriguez, J.M.; Ramírez, E.A. Seasonal Distribution of Alternaria, Aspergillus, Cladosporium and Penicillium Species Isolated in Homes of Fungal Allergic Patients. J. Investig. Allergol. Clin. Immunol. 2006, 16, 357–363. [Google Scholar]

- Bafadhel, M.; Greening, N.J.; Harvey-Dunstan, T.C.; Williams, J.E.; Morgan, M.D.; Brightling, C.E.; Hussain, S.F.; Pavord, I.D.; Singh, S.J.; Steiner, M.C. Blood Eosinophils and Outcomes in Severe Hospitalized Exacerbations of COPD. Chest 2016, 150, 320–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xerinda, S.; Neves, N.; Santos, L.; Sarmento, A. Endotracheal Tuberculosis and Aspergillosis Coinfection Manifested as Acute Respiratory Failure: A Case Report. Bioresources 2011, 6, 2435–2447. [Google Scholar]

- Hosseini, M.; Shakerimoghaddam, A.; Ghazalibina, M.; Khaledi, A. Aspergillus Coinfection among Patients with Pulmonary Tuberculosis in Asia and Africa Countries: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Cross-Sectional Studies. Microb. Pathog. 2020, 141, 104018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakrabarti, H.S.; Das, S.; Gupta-Bhattacharya, S. Outdoor Airborne Fungal Spora Load in a Suburb of Kolkata, India: Its Variation, Meteorological Determinants and Health Impact. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 2012, 22, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, R.I.; Miletto, M.; Taylor, J.W.; Bruns, T.D. The diversity and distribution of fungi on residential surfaces. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e78866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jyoti, J.; Malik, C.P. Seed Deterioration: A Review. Int. J. Life Sci. Biotechnol. Pharm. Res. 2013, 2, 373–386. [Google Scholar]

- Katre, J. Studies on Aeromycology of Railway Station, Nagpur. Master’s Thesis, P.G. Dept. of Botany, R.T.M. Nagpur University, Nagpur, India, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kayarkar, A.; Bhajbhuje, M.N. Biodiversity of Aeromycoflora from Indoor Environment of Library. Int. J. Life Sci. 2014, A2, 21–24. [Google Scholar]

- Verma, S.; Thakur, B.; Karkun, D.; Shrivastav, R. Studies of Aeromycoflora of District and Session Court of Durg, Chhattisgarh. J. Bio. Innov. 2013, 2, 146–151. [Google Scholar]

- Lanjewar, S.; Sharma, K. Intramural Aeromycoflora of Rice Mill of Chhattisgarh. DAMA Int. 2014, 1, 39–45. [Google Scholar]

- Dongre, P.; Bhajbhuje, M.N. Biodiversity of Fungal Flora of Outdoor Environment of Botanical Garden; P.G. Dept. of Botany, R.T.M. Nagpur University: Nagpur, India, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Horner, W.E.; Helbling, A.; Salvaggio, J.E.; Lehrer, S.B. Fungal Allergens. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 1995, 8, 161–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurup, V.P.; Shen, H.-D.; Banerjee, B. Respiratory Fungal Allergy. Microbes Infect. 2000, 2, 1101–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurup, V.P. Fungal Allergy. In Handbook of Fungal Biotechnology; Arora, N., Ed.; Dekker: New York, NY, USA, 2003; pp. 515–525. [Google Scholar]

| Fungal Types | Total Avg. Colonies | Percentage Contribution |

|---|---|---|

| Zygomycota | 29 | 3.58 |

| Mucor pusillus | 7 | 0.87 |

| Rhizopus stolonifer | 22 | 2.72 |

| Ascomycota | 520 | 64.28 |

| Aspergillus candidus | 23 | 2.84 |

| Aspergillus clavatus | 20 | 2.47 |

| Aspergillus flavus | 112 | 13.84 |

| Aspergillus fumigatus | 123 | 15.20 |

| Aspergillus glaucus | 9 | 1.11 |

| Aspergillus japonicus | 3 | 0.37 |

| Aspergillus nidulans | 6 | 0.74 |

| Aspergillus niger | 102 | 12.61 |

| Aspergillus sp. | 11 | 1.36 |

| Aspergillus versicolor | 36 | 4.45 |

| Drechslera sp. | 12 | 1.48 |

| Epicoccum nigrum | 10 | 1.24 |

| Penicillium citrinum | 16 | 1.98 |

| Penicillium chrysogenum | 18 | 2.22 |

| Penicillium oxalicum | 16 | 1.98 |

| Periconia | 3 | 0.37 |

| Deuteromycota | 260 | 32.14 |

| Alternaria alternata | 98 | 12.11 |

| Alternaria solani | 6 | 0.74 |

| Curvularia lunata | 8 | 0.99 |

| Cladosporium cladosporoides | 123 | 15.20 |

| Fusarium solanii | 2 | 0.25 |

| Fusarium oxysporum | 11 | 1.36 |

| Helminthosporium | 2 | 0.25 |

| Nigrospora sp. | 3 | 0.37 |

| Pyricularia sp. | 5 | 0.62 |

| Trichothecium roseum | 2 | 0.25 |

| Source | DF | Sum of Square | Mean Square | F Statistic (df1, df2) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regression | 1 | 127.4509 | 127.4509 | 215.1586 (1,24) | 1.765 × 10−13 |

| Residual | 24 | 14.2166 | 0.5924 | ||

| Total | 25 | 141.6674 | 5.6667 |

| Fungal Taxon | Total % of Positive Response (n = 38) | +1 SPT (%) (n = 38) | +2 SPT (%) (n = 38) | +3 SPT (%) (n = 38) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aspergillus fumigatus | 39.5 | 61.2 | 45.9 | 35.8 |

| Name of the Fungal Antigen | Protein Conc. of Crude Antigen | Protein Conc. of Tris-Phenol Fraction |

|---|---|---|

| Aspergillus fumigatus | 13.9 µg/µL | 27.9 µg/µL |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Basak, T.; Pradhan, R.; Mallik, A.; Roy, A. Investigation of Aeromycoflora in the Library and Reading Room of Midnapore College (Autonomous): Impact on Human Health. Aerobiology 2026, 4, 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/aerobiology4010003

Basak T, Pradhan R, Mallik A, Roy A. Investigation of Aeromycoflora in the Library and Reading Room of Midnapore College (Autonomous): Impact on Human Health. Aerobiology. 2026; 4(1):3. https://doi.org/10.3390/aerobiology4010003

Chicago/Turabian StyleBasak, Tanmoy, Rajarshi Pradhan, Amrita Mallik, and Abhigyan Roy. 2026. "Investigation of Aeromycoflora in the Library and Reading Room of Midnapore College (Autonomous): Impact on Human Health" Aerobiology 4, no. 1: 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/aerobiology4010003

APA StyleBasak, T., Pradhan, R., Mallik, A., & Roy, A. (2026). Investigation of Aeromycoflora in the Library and Reading Room of Midnapore College (Autonomous): Impact on Human Health. Aerobiology, 4(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/aerobiology4010003