Arteriovenous Fistula with Pseudoaneurysm and Facial Palsy Following Bilateral Sagittal Split Osteotomy: A Case Report

Abstract

1. Introduction

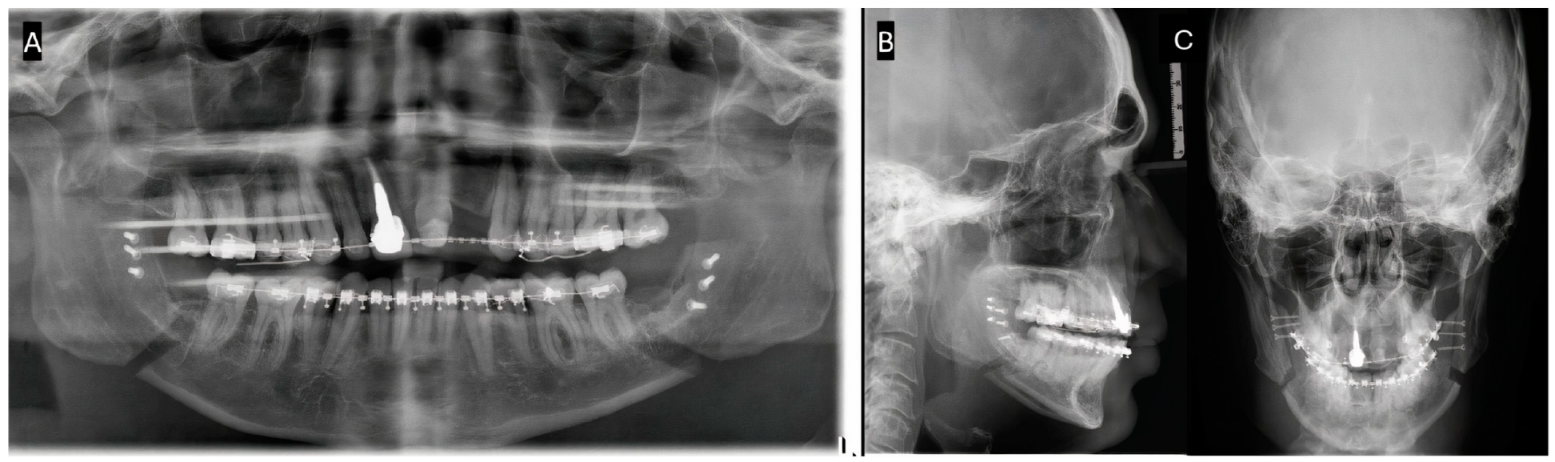

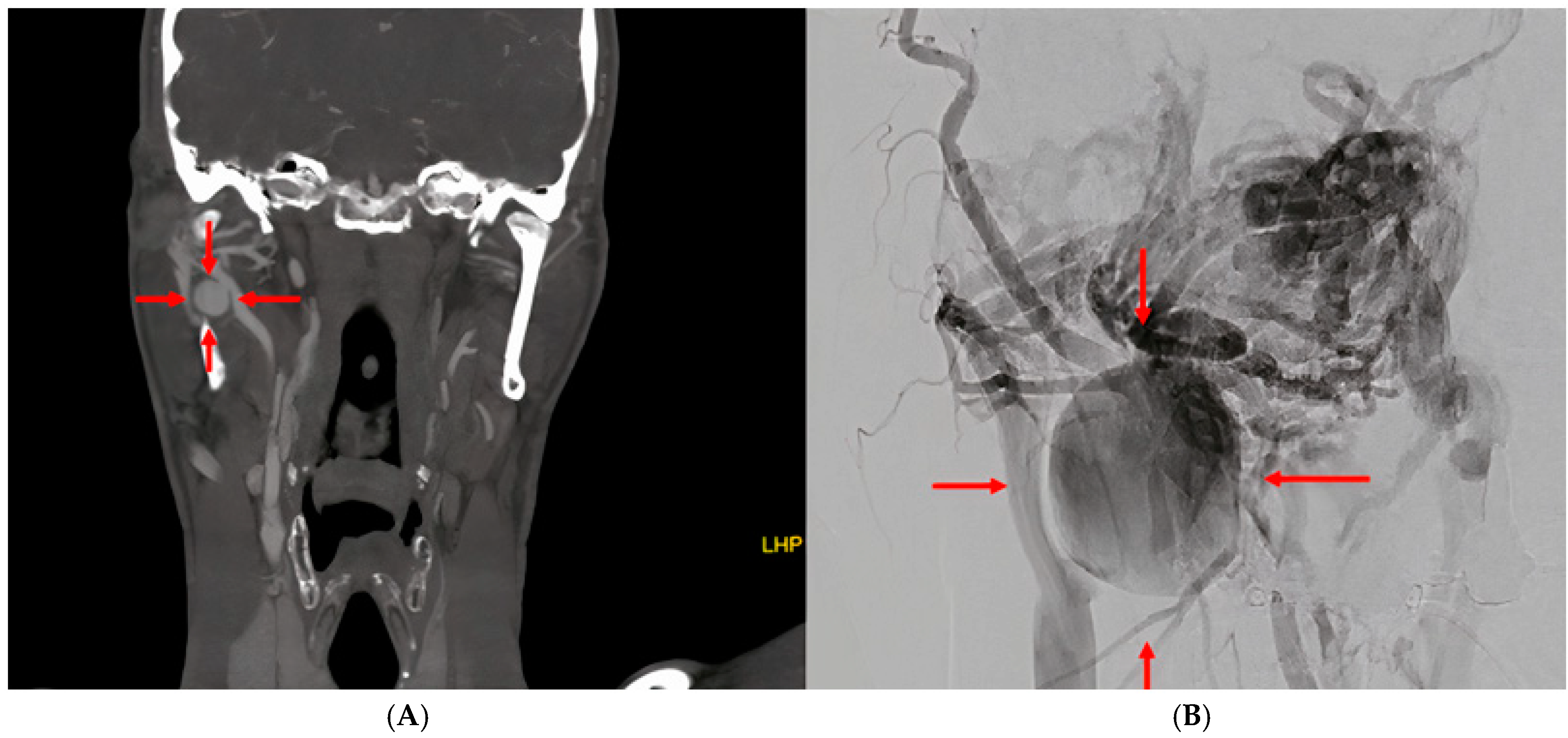

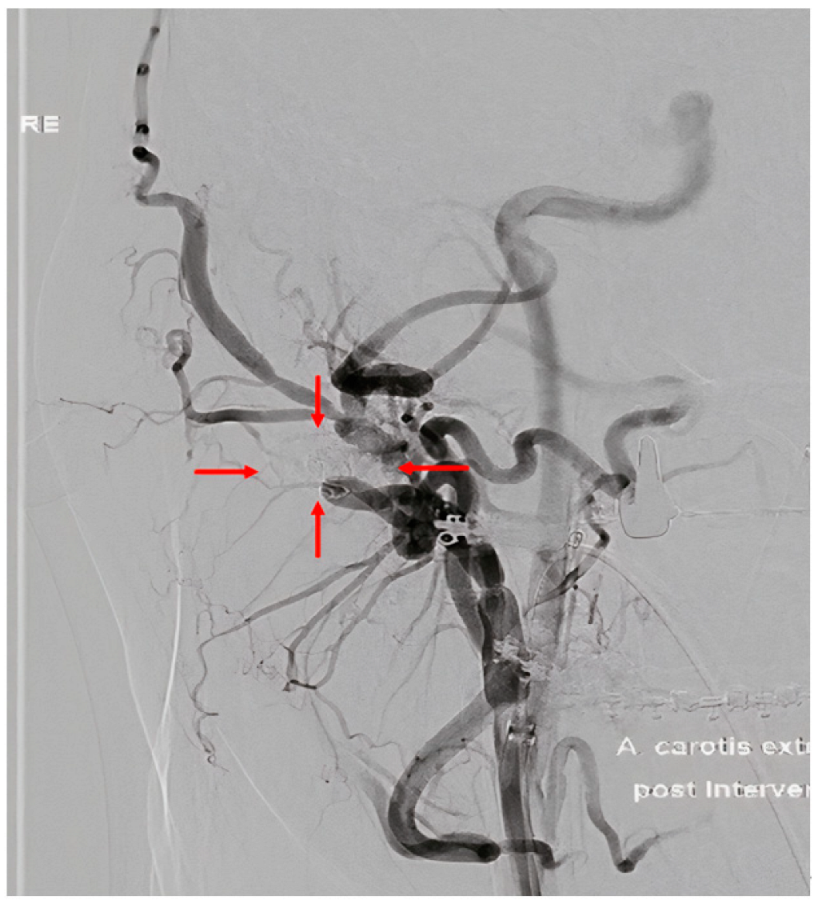

2. Case Report

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Seifert, L.B.; Langhans, C.; Berdan, Y.; Zorn, S.; Klos, M.; Landes, C.; Sader, R. Comparison of two surgical techniques (HOO vs. BSSO) for mandibular osteotomies in orthognathic surgery—A 10-year retrospective study. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2023, 27, 341–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A.; Kaur, A.; Singh, M.; Rattan, V.; Rai, S. Signs and Symptoms Tell All-Pseudoaneurysm as a Cause of Postoperative Bleeding after Orthognathic Surgery-Report of a Case and a Systematic Review of Literature. J. Maxillofac. Oral Surg. 2021, 20, 345–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.C.; O’Ryan, F.; Beckley, M.L.; Young, H.Y.; Poor, D. Pseudoaneurysm of a branch of the maxillary artery following mandibular sagittal split ramus osteotomy: Case report and review of the literature. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2007, 65, 1807–1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunsuck, E. A modified intraoral sagittal splitting technic for correction of mandibular prognathism. J. Oral Surg. 1968, 26, 249–252. [Google Scholar]

- Epker, B. Modifications in the sagittal osteotomy of the mandible. J. Oral Surg. 1977, 35, 157–159. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Möhlhenrich, S.C.; Kniha, K.; Peters, F.; Ayoub, N.; Goloborodko, E.; Hölzle, F.; Fritz, U.; Modabber, A. Fracture patterns after bilateral sagittal split osteotomy of the mandibular ramus according to the Obwegeser/Dal Pont and Hunsuck/Epker modifications. J. Cranio-Maxillofac. Surg. 2017, 45, 762–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brusati, R.; Fiamminghi, L.; Sesenna, E.; Gazzotti, A. Functional disturbances of the inferior alveolar nerve after sagittal osteotomy of the mandibular ramus: Operating technique for prevention. J. Maxillofac. Surg. 1981, 9, 123–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ow, A.; Cheung, L.K. Skeletal Stability and Complications of Bilateral Sagittal Split Osteotomies and Mandibular Distraction Osteogenesis: An Evidence-Based Review. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2009, 67, 2344–2353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobayashi, T.; Izumi, N.; Kojima, T.; Sakagami, N.; Saito, I.; Saito, C. Progressive condylar resorption after mandibular advancement. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2012, 50, 176–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piñeiro-Aguilar, A.; Somoza-Martín, M.; Gandara-Rey, J.M.; García-García, A. Blood loss in orthognathic surgery: A systematic review. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2011, 69, 885–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwaiger, M.; Wallner, J.; Edmondson, S.-J.; Mischak, I.; Rabensteiner, J.; Gary, T.; Zemann, W. Is there a hidden blood loss in orthognathic surgery and should it be considered? Results of a prospective cohort study. J. Cranio-Maxillofac. Surg. 2021, 49, 545–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avelar, R.L.; Goelzer, J.G.; Becker, O.E.; de Oliveira, R.B.; Raupp, E.F.; de Magalhães, P.S.C. Embolization of pseudoaneurysm of the internal maxillary artery after orthognathic surgery. J. Craniofacial Surg. 2010, 21, 1764–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, R.; Lew, D.; Giyanani, V.L.; Gerlock, A. False aneurysm complicating orthognathic surgery. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 1987, 45, 57–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steel, B.J.; Cope, M.R. Unusual and rare complications of orthognathic surgery: A literature review. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2012, 70, 1678–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AbuKaraky, A.; Al Mousa, M.; Samara, O.A.; Baqain, Z.H. Pseudoaneurysm in the inferior alveolar artery following a bad split in bilateral sagittal split osteotomy. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2021, 50, 798–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bykowski, M.R.; Hill, A.; Garland, C.; Tobler, W.; Losee, J.E.; Goldstein, J.A. Ruptured Pseudoaneurysm of the Maxillary Artery and Its Branches Following Le Fort I Osteotomy: Evidence-Based Guidelines. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2018, 29, 998–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenberg, I.; Austin, J.C.; Wright, P.G.; King, R.E. The effect of experimental ligation of the external carotid artery and its major branches on haemorrhage from the maxillary artery. Int. J. Oral Surg. 1982, 11, 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keeling, A.N.; McGrath, F.P.; Lee, M.J. Interventional Radiology in the Diagnosis, Management, and Follow-Up of Pseudoaneurysms. CardioVascular Interv. Radiol. 2009, 32, 2–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cornwall, J.W.; Png, C.Y.M.; Han, D.K.; Tadros, R.O.; Marin, M.L.; Faries, P.L. Endovascular techniques in the treatment of extracranial carotid artery aneurysms. J. Vasc. Surg. 2021, 73, 2031–2035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obayi, I.J.; Cornwall, J.W.; Rao, A.G.; Han, D.K.; Tadros, R.O.; Marin, M.L.; Faries, P.L. Advancements in Endovascular Treatment of Extracranial Carotid Artery Aneurysms. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 2024; ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ivanic-Sefcikova, M.; Starke, V.; Groessing, L.; Augustin, M.; Schwaiger, M.; Zemann, W. Arteriovenous Fistula with Pseudoaneurysm and Facial Palsy Following Bilateral Sagittal Split Osteotomy: A Case Report. Complications 2025, 2, 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/complications2010003

Ivanic-Sefcikova M, Starke V, Groessing L, Augustin M, Schwaiger M, Zemann W. Arteriovenous Fistula with Pseudoaneurysm and Facial Palsy Following Bilateral Sagittal Split Osteotomy: A Case Report. Complications. 2025; 2(1):3. https://doi.org/10.3390/complications2010003

Chicago/Turabian StyleIvanic-Sefcikova, Michala, Vasco Starke, Lukas Groessing, Michael Augustin, Michael Schwaiger, and Wolfgang Zemann. 2025. "Arteriovenous Fistula with Pseudoaneurysm and Facial Palsy Following Bilateral Sagittal Split Osteotomy: A Case Report" Complications 2, no. 1: 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/complications2010003

APA StyleIvanic-Sefcikova, M., Starke, V., Groessing, L., Augustin, M., Schwaiger, M., & Zemann, W. (2025). Arteriovenous Fistula with Pseudoaneurysm and Facial Palsy Following Bilateral Sagittal Split Osteotomy: A Case Report. Complications, 2(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/complications2010003