Addressing Non-Uniqueness in Guided Wave Tomography for Limited-View Corrosion Mapping

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Statistical measures to guide system configuration, helping to mitigate non-uniqueness.

- Joint multimode inversion of guided waves , , and , improving the precision of the inversion and reducing the sensitivity to noise.

- A mode filtering technique based on the non-uniform discrete Fourier transform.

2. Background

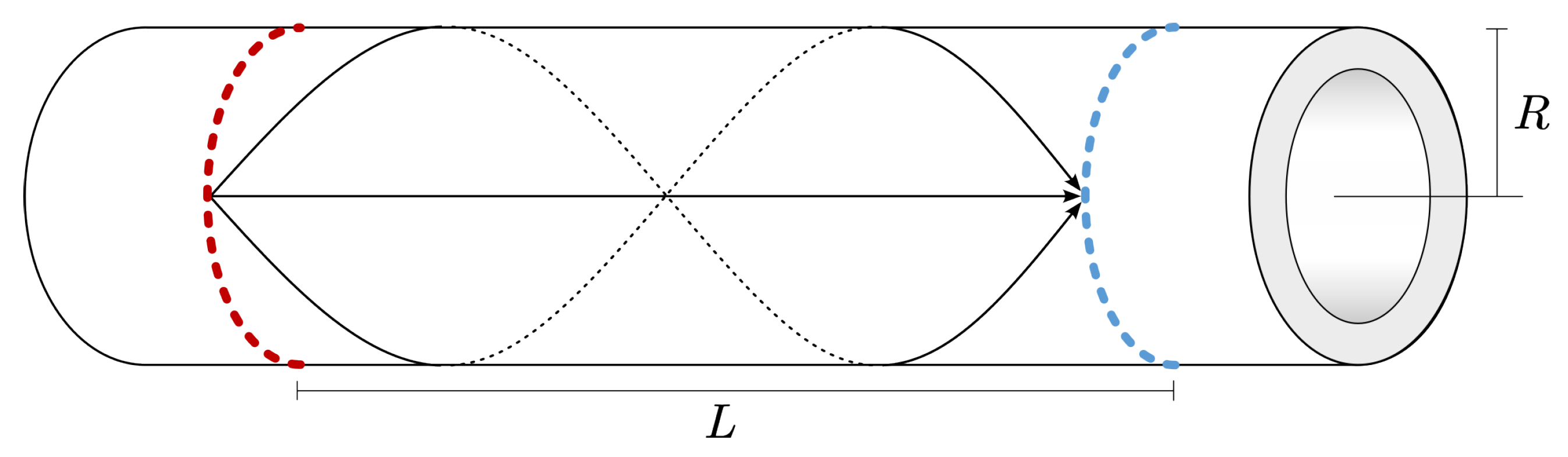

2.1. Guided Wave Tomography

2.2. Full Waveform Inversion

2.2.1. Misfit Functions

2.2.2. Defect Localisation and Parameterisation

2.3. Uncertainty Quantification

2D Misfit Landscapes

3. Modelling

3.1. 3D Elastic Model

3.2. Recursive Wavefield Extrapolation

Noise

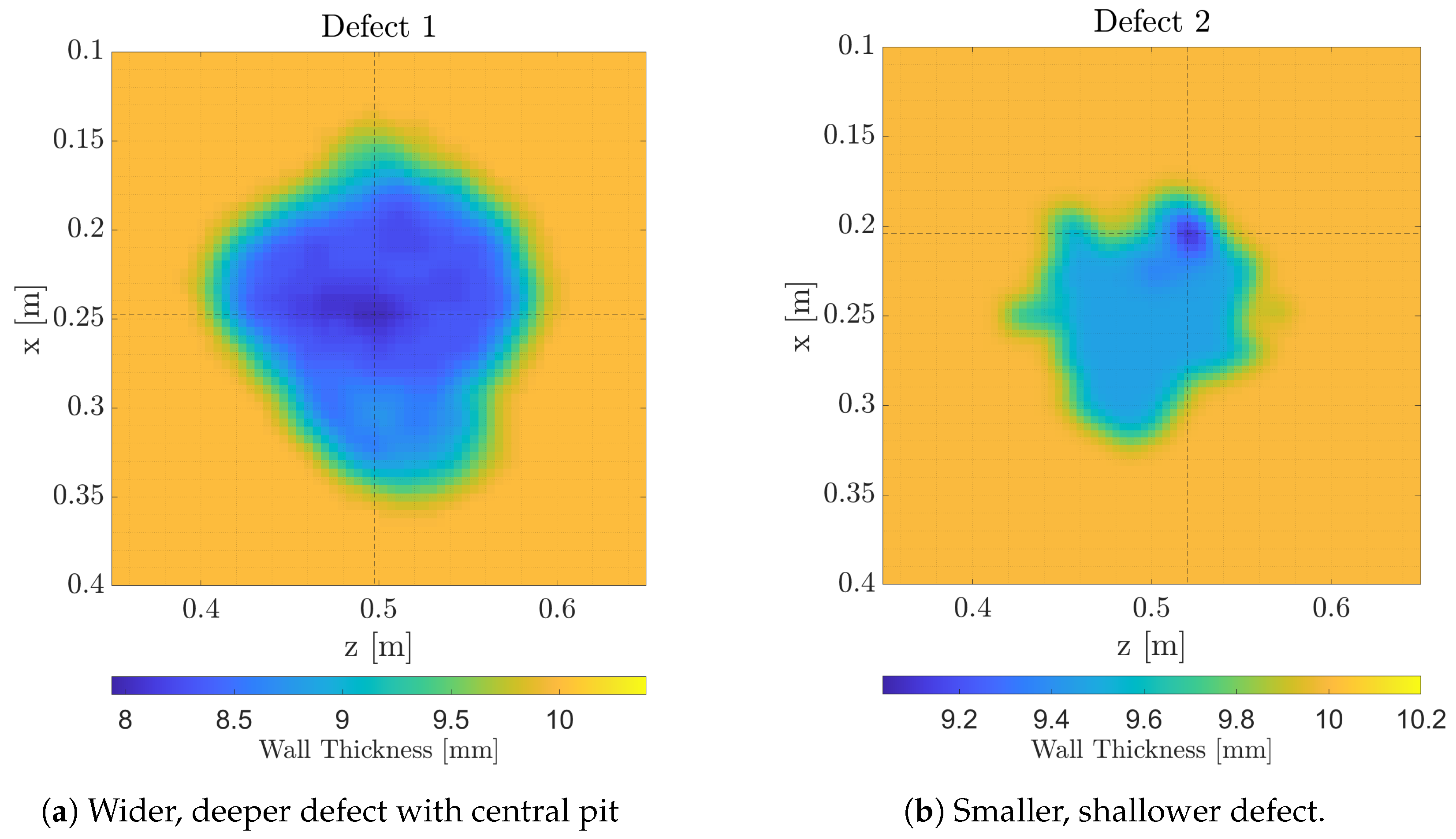

3.3. Defect

3.4. Error Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Tomography on a Regular Grid

4.2. Tomography on an Optimized Grid: Null-Space Perturbation

4.3. Tomography on an Optimised Grid: Uncertainty Quantification

5. Discussion

5.1. Accuracy Versus Precision

5.2. Frequency Selection and Weighting

5.3. Practical Inspection Conditions: Transition from Synthetic to Experimental Data

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Data Processing and NUDFT

Appendix A.1. NUDFT

Appendix A.2. Dispersion Curve Fit

Appendix A.3. Mode Filter

References

- Rose, J.L. Ultrasonic Guided Waves in Solid Media, 1st ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cawley, P.; Alleyne, D. The use of Lamb waves for the long range inspection of large structures. Ultrasonics 1996, 34, 287–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuninetti, V.; Huentemilla, M.; Gómez, Á.; Oñate, A.; Menacer, B.; Narayan, S.; Montalba, C. Evaluating Pipeline Inspection Technologies for Enhanced Corrosion Detection in Mining Water Transport Systems. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huthwaite, P.; Ribichini, R.; Cawley, P.; Lowe, M.J.S. Mode selection for corrosion detection in pipes and vessels via guided wave tomography. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control 2013, 60, 1165–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belanger, P.; Cawley, P.; Thompson, D.O.; Chimenti, D.E. Lamb Wave Tomogrpahy to Evaluate the Maximum Depth of Corrosion Patches. AIP Conf. Proc. 2008, 975, 1290–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belanger, P.; Cawley, P. Feasibility of low frequency straight-ray guided wave tomography. NDT E Int. 2009, 42, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belanger, P.; Cawley, P.; Simonetti, F. Guided wave diffraction tomography within the born approximation. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control 2010, 57, 1405–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huthwaite, P.; Simonetti, F. High-resolution guided wave tomography. Wave Motion 2013, 50, 979–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huthwaite, P. Guided wave tomography with an improved scattering model. Proc. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2016, 472, 20160643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huthwaite, P. Improving accuracy through density correction in guided wave tomography. Proc. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2016, 472, 20150832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, A.A.E.; Huthwaite, P.; Pavlakovic, B. High-resolution thickness maps of corrosion using SH1 guided wave tomography. Proc. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2021, 477, 20200380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, J.; Ratassepp, M.; Fan, Z. Limited-view ultrasonic guided wave tomography using an adaptive regularization method. J. Appl. Phys. 2016, 120, 194902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willey, C.; Simonetti, F.; Nagy, P.; Instanes, G. Guided wave tomography of pipes with high-order helical modes. NDT E Int. 2014, 65, 8–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fichtner, A.; Trampert, J. Resolution analysis in full waveform inversion: Resolution in full waveform inversion. Geophys. J. Int. 2011, 187, 1604–1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thurin, J.; Brossier, R.; Métivier, L. Ensemble-based uncertainty estimation in Full Waveform Inversion. Geophys. J. Int. 2019, 219, 1613–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, W.; Geng, Y.; Innanen, K.A. Interparameter trade-off quantification and reduction in isotropic-elastic full-waveform inversion: Synthetic experiments and Hussar land data set application. Geophys. J. Int. 2018, 213, 1305–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, J.; Yang, J.; Ratassepp, M.; Fan, Z. Multi-parameter reconstruction of velocity and density using ultrasonic tomography based on full waveform inversion. Ultrasonics 2020, 101, 106004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virieux, J. (Ed.) An Introduction to Full Waveform Inversion; Society of Exploration Geophysicists: Tulsa, OK, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozdağ, E.; Trampert, J.; Tromp, J. Misfit functions for full waveform inversion based on instantaneous phase and envelope measurements: Misfit functions for full waveform inversion. Geophys. J. Int. 2011, 185, 845–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fichtner, A. Full Seismic Waveform Modelling and Inversion; Advances in Geophysical and Environmental Mechanics and Mathematics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, L.; Chen, S.; Tong, J.; Chen, X.; Zeng, Z.; Liu, Y. Ultrasonic guided wave imaging of pipelines based on physics embedded inversion neural network. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2023, 34, 115401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, J.; Li, J.; Lin, M.; Chen, S.; Chu, G.; Lv, L.; Zhang, P.; Tang, Z.; Liu, Y. Quantitative guided wave imaging with shear horizontal waves and deep convolutional descent full waveform inversion. NDT E Int. 2024, 145, 103141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volker, A.; Bloom, J.; Thompson, D.O.; Chimenti, D.E. Experimental Results of Guided Wave Travel Time Tomography; American Institute of Physics: San Diego, CA, USA, 2011; pp. 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasgado-Moreno, C.O.; Rist, M.; Land, R.; Ratassepp, M. Acoustic Forward Model for Guided Wave Propagation and Scattering in a Pipe Bend. Sensors 2022, 22, 486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassefras, E.; Volker, A.; Verweij, M. Efficient Guided Wave Modelling for Tomographic Corrosion Mapping via One-Way Wavefield Extrapolation. Sensors 2024, 24, 3750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demma, A.; Cawley, P.; Lowe, M.; Roosenbrand, A.; Pavlakovic, B. The reflection of guided waves from notches in pipes: A guide for interpreting corrosion measurements. NDT E Int. 2004, 37, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.; Zhang, J.; Yang, S. Location Detection and Numerical Simulation of Guided Wave Defects in Steel Pipes. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 10403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, S.; Lowe, M.J.S.; Ratassepp, M.; Brett, C. Detection of Axial Cracks in Pipes Using Focused Guided Waves. J. Nondestruct. Eval. 2012, 31, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huthwaite, P. Evaluation of inversion approaches for guided wave thickness mapping. Proc. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2014, 470, 20140063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, J.; Ratassepp, M.; Fan, Z. Guided Wave Tomography Based on Full Waveform Inversion. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control 2016, 63, 737–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, J.; Ratassepp, M.; Fan, Z. Investigation of the reconstruction accuracy of guided wave tomography using full waveform inversion. J. Sound Vib. 2017, 400, 317–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, P.; Huthwaite, P. Quantitative mapping of thickness variations along a ray path using geometrical full waveform inversion and guided wave mode conversion. Proc. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2022, 478, 20210602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, J.; Ratassepp, M.; Fan, Z. Quantification of Thickness Loss in Liquid-loaded Pipes Based on Guided Wave Tomography. In Proceedings of the 7th Asia–Pacific Workshop on Structural Health Monitoring, Hong Kong, China, 12–15 November 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, J.; Jiang, C.; Chen, H. High-Precision Corrosion Detection via SH1 Guided Wave Based on Full Waveform Inversion. Sensors 2023, 23, 9902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brath, A.J.; Simonetti, F.; Nagy, P.B.; Instanes, G. Guided Wave Tomography of Pipe Bends. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control 2017, 64, 847–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Huang, S.; Shen, G.; Wang, S.; Zhao, W. High resolution tomography of pipeline using multi-helical Lamb wave based on compressed sensing. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 317, 125628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarantola, A. Inverse Problem Theory and Methods for Model Parameter Estimation; Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plessix, R.E. A review of the adjoint-state method for computing the gradient of a functional with geophysical applications. Geophys. J. Int. 2006, 167, 495–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fichtner, A.; Trampert, J. Hessian kernels of seismic data functionals based upon adjoint techniques. Geophys. J. Int. 2011, 185, 775–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, I.; Boehm, C.; Zunino, A.; Fichtner, A. Analyzing resolution and model uncertainties for ultrasound computed tomography using Hessian information. In Proceedings of the Medical Imaging 2022: Ultrasonic Imaging and Tomography, San Diego, CA, USA, 23–24 February 2022; Volume 12038, p. 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deal, M.M.; Nolet, G. Nullspace shuttles. Geophys. J. Int. 1996, 124, 372–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Peter, D. Square-Root Variable Metric-Based Nullspace Shuttle: A Characterization of the Nonuniqueness in Elastic Full-Waveform Inversion. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2020, 125, e2019JB018687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fichtner, A.; Zunino, A. Hamiltonian Nullspace Shuttles. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2019, 46, 644–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keating, S.D.; Innanen, K.A. Null-space shuttles for targeted uncertainty analysis in full-waveform inversion. Geophysics 2021, 86, R63–R76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Beller, S.; Lei, W.; Peter, D.; Tromp, J. Pre-conditioned BFGS-based uncertainty quantification in elastic full-waveform inversion. Geophys. J. Int. 2021, 228, 796–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonard, K.R.; Hinders, M.K. Lamb wave tomography of pipe-like structures. Ultrasonics 2005, 43, 574–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Druet, T.; Tastet, J.L.; Chapuis, B.; Moulin, E. Guided Wave Tomography for Corrosion Monitoring in Planar Structures. In Structural Health Monitoring; DEStech Publications, Inc.: Lancaster, PA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Rose, J.L. Natural beam focusing of non-axisymmetric guided waves in large-diameter pipes. Ultrasonics 2006, 44, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Rose, J.L. Excitation and propagation of non-axisymmetric guided waves in a hollow cylinder. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2001, 109, 457–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velichko, A.; Wilcox, P.D. Excitation and scattering of guided waves: Relationships between solutions for plates and pipes. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2009, 125, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, W.; Zhao, X.; Rose, J.L. A Guided Wave Plate Experiment for a Pipe. J. Press. Vessel Technol. 2005, 127, 345–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brath, A.J.; Simonetti, F.; Nagy, P.B.; Instanes, G. Experimental Validation of a Fast Forward Model for Guided Wave Tomography of Pipe Elbows. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control 2017, 64, 859–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuo, P.; Huthwaite, P. Guided wave tomography for quantitative thickness mapping using non-dispersive SH0 mode through geometrical full waveform inversion (GFWI). Proc. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2024, 480, 20240132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fichtner, A.; Kennett, B.L.N.; Igel, H.; Bunge, H.P. Theoretical background for continental- and global-scale full-waveform inversion in the time-frequency domain. Geophys. J. Int. 2008, 175, 665–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maggi, A.; Tape, C.; Chen, M.; Chao, D.; Tromp, J. An automated time-window selection algorithm for seismic tomography. Geophys. J. Int. 2009, 178, 257–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tromp, J.; Tape, C.; Liu, Q. Seismic tomography, adjoint methods, time reversal and banana-doughnut kernels: Seismic tomography, adjoint methods, time reversal and banana-doughnut kernels. Geophys. J. Int. 2004, 160, 195–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Leeuwen, T.; Mulder, W.A. A correlation-based misfit criterion for wave-equation traveltime tomography: Correlation-based traveltime tomography. Geophys. J. Int. 2010, 182, 1383–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratt, R.G. Seismic waveform inversion in the frequency domain, Part 1: Theory and verification in a physical scale model. Geophysics 1999, 64, 888–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fichtner, A.; Bunge, H.P.; Igel, H. The adjoint method in seismology. I. Theory. Phys. Earth Planet. Inter. 2006, 157, 86–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Li, S.; Fomel, S.; Stadler, G.; Ghattas, O. A Bayesian approach to estimate uncertainty for full-waveform inversion using a priori information from depth migration. Geophysics 2016, 81, R307–R323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Wit, R.W.L.; Trampert, J.; van der Hilst, R.D. Toward quantifying uncertainty in travel time tomography using the null-space shuttle. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2012, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratt, R.G.; Shin, C.; Hicks, G.J. Gauss-Newton and full Newton methods in frequency-space seismic waveform inversion. Geophys. J. Int. 1998, 133, 341–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Métivier, L.; Brossier, R.; Operto, S.; Virieux, J. Full Waveform Inversion and the Truncated Newton Method. SIAM Rev. 2017, 59, 153–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saenger, E.H.; Bohlen, T. Finite-difference modeling of viscoelastic and anisotropic wave propagation using the rotated staggered grid. Geophysics 2004, 69, 583–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, J.; Ratassepp, M.; Fan, Z. Quantification of thickness loss in a liquid-loaded plate using ultrasonic guided wave tomography. Smart Mater. Struct. 2017, 26, 125017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Hassefras, E.; Volker, A.; Verweij, M. Addressing Non-Uniqueness in Guided Wave Tomography for Limited-View Corrosion Mapping. NDT 2026, 4, 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/ndt4010001

Hassefras E, Volker A, Verweij M. Addressing Non-Uniqueness in Guided Wave Tomography for Limited-View Corrosion Mapping. NDT. 2026; 4(1):1. https://doi.org/10.3390/ndt4010001

Chicago/Turabian StyleHassefras, Emiel, Arno Volker, and Martin Verweij. 2026. "Addressing Non-Uniqueness in Guided Wave Tomography for Limited-View Corrosion Mapping" NDT 4, no. 1: 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/ndt4010001

APA StyleHassefras, E., Volker, A., & Verweij, M. (2026). Addressing Non-Uniqueness in Guided Wave Tomography for Limited-View Corrosion Mapping. NDT, 4(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/ndt4010001